Treating mental health problems requires a holistic approach and competent professionals. The core attributes of a good psychiatrist described in Good Psychiatric Practice (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2004) include a basic understanding of group dynamics, a critical self-awareness of emotional responses to clinical situations and being a good communicator and listener. For these reasons psychotherapy is recognised as an important part of psychiatric training and the objectives for such training are clearly set out by the College (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/PDF/ptBasic.pdf).

The theoretical knowledge that is required is outlined in the MRCPsych curriculum (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2001). In addition, clinical skills should be practised continually and incrementally under adequate supervision. Implementing the guidelines requires an identified consultant (often a psychotherapist) to coordinate available opportunities. Trainers and educational supervisors should be equipped to monitor progress and trainees should record their experience in logbooks. It is intended that the psychotherapy training should be part of the basic training to be completed before taking the MRCPsych part II examination.

Several studies have compared the previous recommendations for psychotherapy training (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1993) with current practice (Reference Mccrindle, Wildgoose and TillettMcCrindle et al, 2001; Reference Podlejska-Eyres and SternPodlejska-Eyres & Stern, 2003; Reference Pretorius and GoldbeckPretorius & Goldbeck, 2006) and have helped to identify both the deficiencies and the positive experiences of this training. Training schemes differ in geographical size, trainee numbers and organisation from that of the Northern Deanery. However, some similarities exist in the ranges of training offered and the experiences reported.

In a telephone survey of 12 schemes in the south-west (Reference Mccrindle, Wildgoose and TillettMcCrindle et al, 2001), only 10 were offering psychotherapy training, with one psychotherapy post for 95 trainees. However, a range of training was offered, including clinical practice, supervision and theoretical teaching; 7 of the 12 reported using logbooks, and there was limited psychotherapy teaching on the MRCPsych course. Fewer than half provided theoretical teaching, half had significant problems with timetable clashes and 11 out of 12 were dissatisfied with the level of training.

In another study (Reference Podlejska-Eyres and SternPodlejska-Eyres & Stern, 2003) 22 out of 23 trainees completing training in an inner city London rotation were surveyed. The rotation had one psychotherapy post but was geographically small and trainees were well supported for study leave. A long case had been completed by 95%, family/marital therapy by 59%, cognitive—analytic therapy (CAT) by 41%, brief focal therapy by 32%, group therapy by 45% and cognitive—behavioural therapy (CBT) by 73%. Psychologists provided some supervision, and 54% of trainees wanted more psychotherapy experience. Courses were recorded as popular.

Two important initiatives are about to introduce considerable change to psychiatric training. These are the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB) and Modernising Medical Careers.

The aim of this study was to examine the current psychotherapy training experienced by a group of 41 senior unified senior house officers (SHOs) on the Northern Region Rotational Psychiatry Scheme and to evaluate the outcome in terms of practical experience acquired, perceived knowledge acquired and subjective experience.

These trainees have at least 18 months of psychiatry training, and there are two psychotherapy specialty posts. Trainees ought to be aware of the psychotherapy training standards set by the College, and should be working towards these. It was hoped that the survey could then highlight areas where the training could be improved.

Method

A cross-sectional postal survey was sent to the 41 trainees (excluding N.C.) on the Northern Region Senior Unified SHO Training Scheme. A covering letter was enclosed together with a stamped addressed envelope and an invitation to participate in a draw for a £20 book token as an incentive to reply.

The questionnaire covered previous psychiatric experience, awareness of the guidelines for training and use of logbooks. It asked about theoretical teaching and practical experience obtained by the trainee in relation to the College's requirements. Questions were asked about common difficulties in undertaking psychotherapy (such as bleep-free time and room availability) and intended future psychotherapy exposure. A Likert scale was also included to ascertain the subjective overall experience of psychotherapy. Spaces were available for additional comments and clarification.

Results

Response rate

A total of 25 replies were obtained providing a 61% response rate. Despite the offer of a draw for a £20 book token, 15 of the respondents (60%) chose to remain anonymous, which resulted in difficulties in matching experiences to location.

General awareness of trainees

Many trainees (12, 48%) could not identify a consultant responsible for psychotherapy in their area and 14 (56%) were not using logbooks to record their experience. However, most were aware of the College guidelines (76%). The wide geographical distribution might account for the communication with the responsible consultant being better in some areas than others, and in one area there was no consultant. However, the College website provides easy access to the guidelines (http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/PDF/ptBasic.pdf).

Practical skills

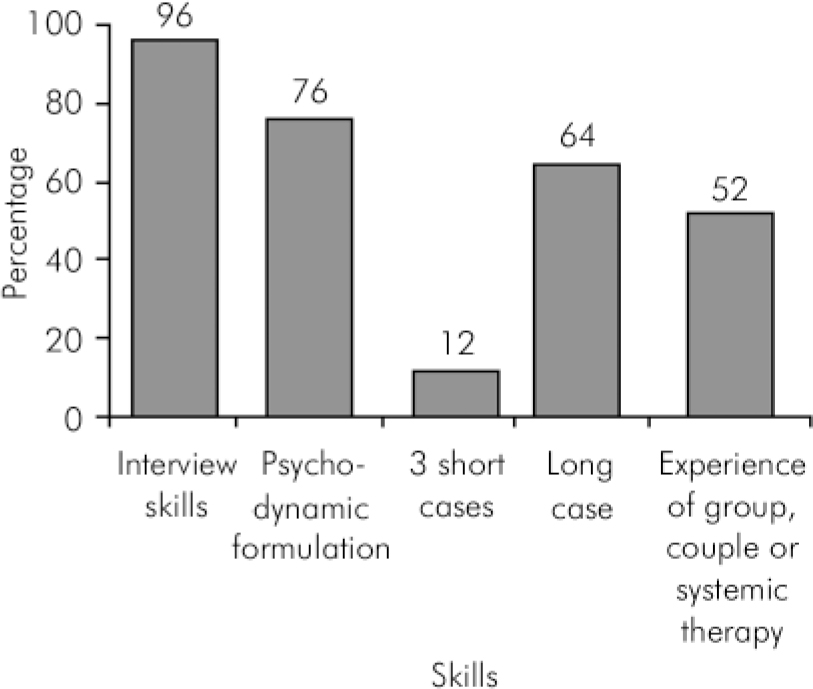

When asked about practical psychotherapy experience, a large majority thought they had achieved the objectives of good interview skills, producing a psychodynamic formulation and conducting a long case, and had experienced group, couple, family or systemic therapy. Few had completed three short cases (Fig. 1). The possible reasons for this include the wide geographical distribution of the scheme, with rotations between hospitals and trusts making it very difficult to find a suitable case and complete the therapy before rotating to a new place. In addition, some areas have only recently identified potential supervisors for short cases.

Theoretical knowledge

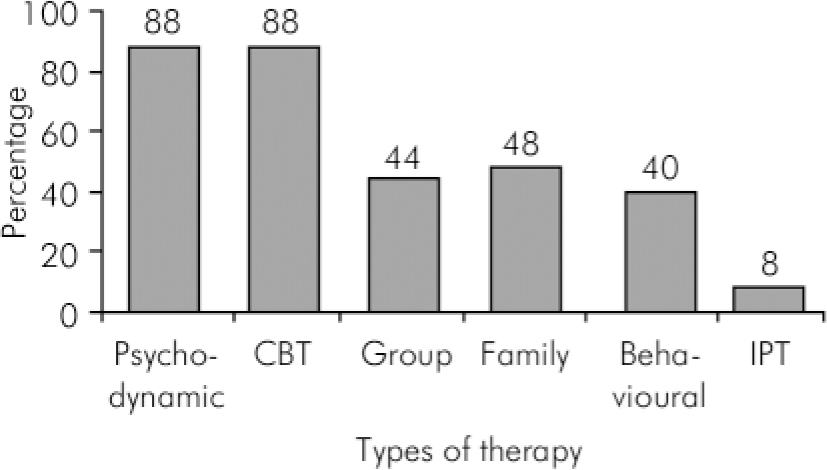

Many of the trainees felt they had received satisfactory teaching in the theory of psychodynamic psychotherapy and CBT. However, far fewer felt they had received teaching in group therapy, family therapy, behavioural therapy or interpersonal therapy (Fig. 2), the last being available in only one location.

Additional experience

In all, 13 trainees (52%) reported they had been on courses in psychotherapy. These included training in group processes, CBT, psychosocial intervention, and family and systemic therapy; one trainee had completed a foundation course in the latter at Northumbria University.

Fig. 1. Practical skills/experience gained by 25 trainees on the Northern Region Senior Unified SHO Training Scheme.

Fig. 2. Theoretical knowledge of therapies gained by 25 trainees on the Northern Region Senior Unified SHO Training Scheme. CBT, cognitive—behavioural therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy.

Practical considerations

Practical arrangements for conducting psychotherapy appeared to be satisfactory in most cases. Bleep-free time and suitable rooms were available for 22 trainees (88%), adequate supervision for 20 (80%) and suitable patients for 17 (68%). From the free-text responses, difficulties reported by trainees included 4% having supervision out of hours, trouble finding a trained CBT supervisor (16%), travelling long distances for supervision (4%), feeling that a 6-month post is too short to find patients and treat them (4%), room booking difficulties (12%) and selection of patients whose problems were too complicated or who lacked motivation (8%).

Subjective experience of psychotherapy training

It was encouraging to find that 23 trainees (92%) rated this experience as satisfactory or better; 17 (68%) intended to consider further training in psychotherapy.

Free-text comments

These varied widely and were both positive and negative. In total, 17 trainees responded in the free-text space; 4 were entirely positive, 7 entirely negative, 3 neutral and 3 demonstrated a mixed response.

The positive comments included finding the experience interesting and useful, particularly the long case. At least three trainees spontaneously reported that it improved understanding of patients’ situations.

However, some SHOs did not know who to approach, two felt they did not discover the psychotherapy training requirements soon enough and two complained of insufficient CBT early in training. The delay in starting a long case was described as frustrating. Transference issues were perceived as difficult (one trainee), as was disengaging patients (one trainee). One student commented that the theory of methods other than psychodynamic therapy was not taught in the MRCPsych course, and one other felt that psychotherapy was irrelevant to clinical practice.

Discussion

The Northern Region Senior Unified SHO Training Scheme covers a wide geographical area which includes more than five National Health Service trusts and many hospital and community sites; this is due to be revised. The posts cover a variety of psychiatric specialties and include two specialist psychotherapy posts at senior SHO grade. There are consultant psychotherapists in post in three locations only, and this could result in a patchy training experience. Two sites have level 1 development (a specialist psychological treatment service with consultant psychotherapist and other specialist staff). Because of the high level of anonymous replies, it is hard to say whether responses from level 1 sites differed from those of trainees working in level 2 services (a consultant psychotherapist working with some other specialist practitioners, but lacking specialist skills available for all training requirements). There were no trainees that would have been working in level 3 sites (no specialist facilities available, no consultant psychotherapist and limited psychological treatment services).

The trainees were at different stages in their psychiatric training and had been in a variety of psychiatric posts in different locations and specialties. The region offers a central MRCPsych course for all trainees, and psychodynamic case discussion groups are provided in all areas of the region. More recently, CBT training and supervision have begun to be provided throughout the region, but this and other therapeutic methods vary in their availability.

As only 61% of eligible trainees responded, it is difficult to establish whether this study is a true representation of all the trainees’ experiences of psychotherapy training. Those who did not reply could be the less motivated trainees, with possibly less knowledge and experience and a worse perception of the subject; although the converse could be true, in that those who were more dissatisfied might have felt more motivated to respond. The response rate might also reflect possible communication difficulties across the scheme.

Currently, trainees must develop interview skills and the ability to make a psychotherapeutic formulation of a psychiatric disorder. The specific skills and core requirements include a minimum of three short-term cases, one from each group of techniques. These cover transference-based therapies, cognitive therapies and integrative therapies. In addition, one long-term case involving any method, and some experience of group psychotherapy and marital or family therapy are required.

The pilot foundation F2 posts in psychiatry have so far proved successful (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2005). Although there is likely to be little time for formal psychotherapy training in posts of 4 months’ duration, these are surely excellent opportunities to introduce trainees, who may go into specialties other than psychiatry, to a psychological approach. These trainees will be expected to achieve competencies in areas such as effective relationships with patients, communication and team-working (Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2005).

The introduction of a unified single-grade training provides the opportunity to distribute psychotherapy training over time and with more continuity. Individual learning plans may shape the trainees’ experiences, with further choice and flexibility in the types of cases chosen. Also, the involvement of patients and carers in psychotherapy training may be a helpful adjunct.

The PMETB emphasises competency-based assessment and trainee performance. Although practice is supervised at present, in the future workplace-based assessments, including mini clinical examinations, direct observed practice and the mini peer-assessment tool, will become the norm (PMETB, 2005). But how will these be carried out in psychotherapy training? It may become increasingly difficult to find suitable patients who also consent to be videotaped, and direct observed practice will be extremely time-consuming in this area. However, some objectives such as interview skills and psychodynamic formulation are currently assessed by such methods in the Northern Region.

In our survey, there was a wide discrepancy between the low numbers aware of a responsible consultant and logbooks, and the high numbers reporting good theoretical and practical knowledge. The forthcoming assessment processes may help us evaluate the discrepancy between subjective (reported) and objective levels of competence.

The results suggest that many trainees feel they are achieving most of the training requirements set by the Royal College of Psychiatrists. A majority of the trainees who responded had had a positive experience of psychotherapy training in the region, and practical considerations such as bleep-free time and the provision of rooms are mostly met. Many trainees have been motivated to pursue additional training in psychotherapy and wish to consider further training in the future. This suggests that psychotherapy training in the region is adequate for most trainees, and can be an enjoyable and useful experience. However, improvements are particularly needed in facilitating short cases, especially CBT; increasing exposure to marital, family or systemic therapy; making all trainees aware of guidelines, use of logbooks; and identifying the consultant responsible for psychotherapy.

Changes to practice are already being implemented, with other members of the multidisciplinary team being increasingly involved as supervisors, more training programmes becoming available and a more structured approach to learning plans, including timescales of when to take on suitable patients. We hope that the reduction in the geographical size of the scheme and the proposed improvements in training continuity will further improve the training experience in psychotherapy. The future looks brighter.

Declaration of interest

S.M. is Chair of the regional psychotherapy trainers’ committee.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.