The tightrope walked by female politicians to maintain electability within the contemporary partisan environment is well documented. Female politicians must negotiate gender stereotypes while also appealing to the ideological and partisan identities of their political base (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016; King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003; Koch Reference Koch2002; Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor Reference Kreiss, Lawrence and McGregor2020; Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018; McDermott Reference McDermott1998). These prerogatives influence the behavior of female elected officials, including the language with which they communicate to the public (Bligh and Kohles Reference Bligh and Kohles2008; Dittmar Reference Dittmar2015; Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2014; Holman Reference Holman2016; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021; Wineinger and Nugent Reference Wineinger and Nugent2020). Among other factors, moral rhetoric is an important dimension of political communication in which the interacting influences of gender and party are evident.

Morality is central to the dynamics of group identity and candidate evaluations (Brambilla and Leach Reference Brambilla and Leach2014; Clifford Reference Clifford2014; Leach et al. Reference Leach, Ellemers and Barreto2007; Pagliaro, Ellemers, and Barreto Reference Pagliaro, Ellemers and Barreto2011). Conveying morality through public rhetoric serves as a means by which politicians may signal their partisan credentials, particularly insofar as liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans are guided by different moral intuitions (Clifford Reference Clifford2020; Graham, Haidt, and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009; Kraft Reference Kraft2018). At the same time, femininity and masculinity are associated with distinct moral characteristics (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002; Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011), the perception of which may benefit or undermine a politician’s partisan appeal depending on how that politician’s gender and partisan identity intersect (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2016; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021). Given the salience of morality to ideologically sorted partisan voters, and given the gendered nature of morality, we examine moral rhetoric as a discursive device with which female politicians may strategically navigate the gendered landscape of partisan politics.

Importantly, it is not just perceptions of moral characteristics that take on gendered contours. To the contrary, there is evidence that males and females in the mass public actually differ in their moral intuitions (Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Iyer, Nosek, Haidt, Koleva and Ditto2011). In this article, we bring these literatures into conversation and hypothesize how gender shapes elite moral rhetoric, given the insights of scholarship on partisanship, liberal-conservative ideology, gender stereotypes, and mass moral psychology. To our knowledge, this is the first study to integrate these areas of research and examine their implications for gender dynamics in elite moral rhetoric, thus bridging a fundamental gap between formerly isolated research agendas. We do so by examining a novel corpus of 2.23 million tweets by members of Congress (MCs). We use the framework of moral foundations theory (MFT) to analyze how gender impacts the kinds of moral concerns emphasized in MCs’ tweets.

Ultimately, we demonstrate that gender uniquely shapes elite moral rhetoric; however, we find that political party conditions the influence of gender. In comparison with their male copartisans, female Democrats use more language evoking “feminine” moral concerns—specifically, those related to the care foundation. Furthermore, female Democrats use less language evoking “masculine” moral concerns—specifically, those related to the authority foundation. In addition, female Democrats use less language evoking moral concerns related to the loyalty foundation, a pattern that mirrors gender differences found in mass psychology. By contrast, female Republicans are indistinguishable from their male copartisans across all five moral foundations (care, fairness, authority, loyalty, and purity).

Our results suggest that moral rhetoric is an understudied domain in which gender and party intersect to shape elite political communication. On the whole, the gendered patterns of moral rhetoric demonstrated here shed light on how female politicians use discursive strategies to navigate the partisan era while simultaneously exhibiting partial consistency with mass psychological gender differences.

Literature Review

Electoral Incentives and Moral Rhetoric

Representatives, male and female alike, are powerfully guided by the objective of getting reelected (Mayhew Reference Mayhew1974). As part of their efforts toward this end, representatives communicate to the public with strategic consideration of voters’ perceptions (Fenno Reference Fenno1978; Grimmer Reference Grimmer2013). Through their public messaging, elected officials attempt to align themselves with the groups from whom they seek political support (Edelman Reference Edelman1964; Kreiss, Lawrence, and McGregor Reference Kreiss, Lawrence and McGregor2020). Forging a shared sense of identity through rhetoric contributes to persuasiveness (Leach Reference Leach, Bauer and Gaskell2011) regarding one’s political credentials and beyond.

In an era of polarization when partisanship has increasingly taken on salience as a social identity (Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018), the electoral incentive motivates representatives to signal their partisan identity through political communication. In this article, we argue that moral rhetoric can serve as a partisan signal insofar as it conveys the enactment of moral in-group norms upheld within the Democratic and Republican Parties. Nonetheless, perceptions of morality are gendered, with certain moral characteristics considered to be feminine and others masculine (discussed further later). As such, moral rhetoric offers both an opportunity and a challenge for female politicians who seek to signal their partisan identity while also navigating the gender stereotypes that shape their public reception.

Moral rhetoric has social identity implications that are acutely relevant to politicians. Perceptions of morality dominate processes of impression formation (Brambilla and Leach Reference Brambilla and Leach2014), and individuals tend to observe moral in-group norms as a way to earn respect (Pagliaro, Ellemers, and Barreto Reference Pagliaro, Ellemers and Barreto2011). When in-group members demonstrate adherence to moral in-group norms, fellow members experience greater in-group pride (Leach, Ellemers, and Barreto Reference Leach, Ellemers and Barreto2007). Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, moral rhetoric in party messaging amplifies feelings of pride, which, in turn, mobilize copartisan voters (Jung Reference Jung2020).

Using moral rhetoric to engender pride and secure respect among a partisan base constitutes a strategic opportunity. Conversely, rhetorically transgressing moral norms is risky, insofar as transgressions can lead to exclusion from the in-group (Brambilla et al. Reference Brambilla, Sacchi, Pagliaro and Ellemers2013). In the political realm, this might entail constituents voting out a copartisan incumbent.

Extant research demonstrates the central role of morality in polarization (Garrett and Bankert Reference Garrett and Bankert2018; Tappin and McKay Reference Tappin and McKay2019), the reinforcing impact of moral discourse on political division (Clifford et al. Reference Clifford, Jerit, Rainey and Motyl2015; Day et al. Reference Day, Fiske, Downing and Trail2014), and the emotionalizing effect of moral appeals more generally (Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz2018)—all of which raise the stakes of moral rhetoric for partisan identity and representatives’ strategic motivations. When it comes to the question of which moral concerns matter for Democrats and which matter for Republicans, we draw upon MFT to develop expectations about how the party-ideology nexus impacts the relationship between gender and elite moral rhetoric.

Morality as an Ideological and Partisan Signal

MFT is a prominent framework in moral psychology for analyzing differences in moral intuition. According to this framework, five psychological foundations underpin the spectrum of emotion-driven, reflexively generated moral judgments (Haidt Reference Haidt2001; Haidt and Graham Reference Haidt and Graham2007). These foundations are termed care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and purity. While the care foundation captures sensitivity to individual suffering, the fairness foundation captures sensitivity to exploitation (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Haidt and Joseph Reference Haidt and Joseph2004). Insofar as these foundations implicate individual well-being, care and fairness are categorized as “individualizing” foundations (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Haidt and Joseph Reference Haidt and Joseph2004).

In contrast with care and fairness, the remaining three foundations capture moral concerns pertinent to the well-being of a cohesive society and thus are termed “binding” foundations. These binding foundations—authority, loyalty, and purity—encompass sensitivities to hierarchy, allegiance, and sanctity, respectively (Haidt Reference Haidt2012; Haidt and Joseph Reference Haidt and Joseph2004). Notably, the primary finding to emerge from MFT research is that liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Liberals rely more on care and fairness, while conservatives rely more on authority, loyalty, and purity (Graham, Haidt, and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009).

These differences in liberal-conservative morality correlate with patterns of partisan voting, with endorsement of the individualizing foundations predicting Democratic votes and endorsement of the binding foundations predicting Republican votes (Franks and Scherr Reference Franks and Scherr2015). In a similar vein, when evaluating candidates, Democrats place more importance on traits associated with the individualizing foundations (i.e., being compassionate and fair-minded), while Republicans prioritize traits associated with the binding foundations (i.e., being respectful, loyal, and wholesome) (Clifford Reference Clifford2020).

It is worth acknowledging the ongoing debate regarding the causal relationship between moral foundations and liberal-conservative ideology. While the core of MFT suggests moral foundations are the immutable source of political ideology, recent scholarship has disputed this premise, arguing instead that ideology is more psychologically primary than moral intuitions (Hatemi, Crabtree, and Smith Reference Hatemi, Crabtree and Smith2019). In this article, we remain agnostic regarding this causal debate. Instead, we proceed on the basis of research demonstrating the utility of MFT for mapping ideological and partisan differences in political reasoning, persuasion, and perception.

For instance, Americans spontaneously use moral arguments when assessing parties and candidates, with liberals more frequently emphasizing the individualizing foundations and conservatives more frequently emphasizing the binding foundations (Kraft Reference Kraft2018). Furthermore, Americans are aware of which moral arguments appeal to which ideological camp, as demonstrated by research participants’ recognition that arguments reframed in terms of the binding foundations will be more persuasive to conservatives, and vice versa (Feinberg and Willer Reference Feinberg and Willer2015). Likewise, there is evidence indicating that Americans associate foundation-specific rhetoric with ideological identity, insofar as morally reframed arguments can be persuasive because they impact perceptions about whether the messenger is an ideological in-group member (see Feinberg and Willer Reference Feinberg and Willer2019). On the whole, the literature implies that moral foundations have ideological associations and, by extension, partisan implications, given the context of liberal and conservative sorting across the Democratic and Republican Parties (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009; Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018).

Party Image, Gender Stereotypes, and Morality

The intersection of moral foundations, ideology, and partisanship creates a political environment in which representatives have an incentive to speak in the moral terms of the partisan voters from whom they seek support. For female politicians, this incentive is complicated by the prerogative of maneuvering around gender stereotypes, which operate at multiple levels and involve morally loaded attributions.

Scholars of gender stereotypes have documented the pervasiveness of ideas about femininity and masculinity among the American public. Feminine stereotypes descriptively and prescriptively associate women with communal roles and characterize them as affectionate, helpful, kind, sympathetic, interpersonally sensitive, and gentle (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). In contrast, masculine stereotypes descriptively and prescriptively associate men with agentic roles and characterize them with traits of aggressiveness and dominance that connote traditional conceptions of leadership (Koenig et al. Reference Koenig, Eagly, Mitchell and Ristikari2011). Whether these stereotypes become activated and influential over candidate preferences may depend powerfully on rhetorical strategy and political context (Bauer Reference Bauer2015; Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017; Gordon, Shafie, and Crigler Reference Gordon, Shafie and Crigler2003; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993; Krupnikov and Bauer Reference Krupnikov and Bauer2014).

Gender stereotypes do not just impact individual politicians; they shape the public images of the political parties themselves. Americans explicitly and implicitly associate the Democratic Party with stereotypically feminine characteristics and the Republican Party with stereotypically masculine characteristics (Winter Reference Winter2010). These associations are theoretically (though not causally) traced by Winter (Reference Winter2010) to changes within both parties in terms of their embrace or rejection of women’s rights advocacy throughout the 1970s and 1980s (see Adams Reference Adams1997; Wolbrecht Reference Wolbrecht2000).

The research of linguist George Lakoff suggests that the gendering of the political parties in terms of their public images is morally loaded. According to this work, liberals and conservatives implicitly conceptualize the responsibility of government in the moral and gendered terms of metaphorical parenthood (Lakoff Reference Lakoff2002). For liberals, and by extension Democrats, the government should act as a nurturing parent, whereas for conservatives, and by extension Republicans, the government should act as a strict father (Lakoff Reference Lakoff2002). Lakoff’s framework can be situated alongside that of MFT, insofar as liberals’ preference for a metaphorically nurturant government tracks with their prioritization of the care foundation, and conservatives’ preference for a metaphorically strict government tracks with their prioritization of the authority foundation.

When it comes to elite rhetoric, Lakoff’s framework differentiates Democratic and Republican messaging at the level of presidential advertisements, with Democrats emphasizing moral metaphors of nurturant parenthood and Republicans emphasizing those of strict fatherhood (Moses and Gonzales Reference Moses and Gonzales2015). Related differences across gender are likewise evident, with female mayors emphasizing nurturant parenthood and male mayors emphasizing strict fatherhood (Holman Reference Holman2016). Notably, these gender effects are documented in the nonpartisan context of mayoral rhetoric, thus leaving a gap at the intersection of gender and partisanship that our study addresses.

Taken as a whole, the literature suggests that the moral foundations themselves are liable to carry not only ideological and partisan associations, but also gendered associations in the minds of the American public. We argue that these ideological, partisan, and gendered associations shape strategic motivations, which, in turn, will be reflected in the way female representatives use moral rhetoric. Female politicians navigate two levels of gendered politics—that of their own party and that of their personal gender identity. For Republican female politicians, the path is particularly fraught with catch-22s, as their personal gender identity is associated with the partisan out-group, the Democratic Party (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2016; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021). For Democratic female politicians, embracing feminine stereotypes might play to their favor because of the party’s feminine image (Koch Reference Koch2002). In the next section, we discuss further why the two parties have different incentives regarding the use of gender-stereotypic moral rhetoric. Before doing so, however, we consider the broader context of gender and moral psychology among the public.

Theory and Hypotheses

Gender Differences in Moral Psychology

First, through a mass psychology lens, we develop an initial set of hypotheses in which gender has a distinct impact on elite moral rhetoric that is independent of partisanship. The literature cited here focuses on how gender shapes moral foundations and other aspects of moral difference among the public.

In addition to studying differences between liberals and conservatives, MFT scholars have demonstrated that women are more concerned with the care, fairness, and purity foundations than men, even when controlling for ideology (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Iyer, Nosek, Haidt, Koleva and Ditto2011). These differences between women and men are stronger than differences between Eastern and Western cultures (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Iyer, Nosek, Haidt, Koleva and Ditto2011), suggesting that gender has a powerful influence over moral psychology. Beyond these findings, scholarship on moral foundations and gender is limited; however, research on related psychological frameworks provides additional insight regarding gender differences in morality.

The MFT finding that females rely more on the care foundation aligns with the argument that women heed an “ethic of care” that is distinct from more masculine modes of morality (Gilligan Reference Gilligan1982). In response to stimuli portraying harmful behavior, women evince greater neural activity associated with empathic processes, which is interpreted as reflecting this ethic of care (Harenski et al. Reference Harenski, Antonenko, Shane and Kiehl2008). Furthermore, women evince more deontological modes of moral judgment in response to depictions of harm (Fumagelli et al. Reference Fumagalli, Ferrucci, Mameli, Marceglia, Mrakic-Sposta, Zago, Lucchiari, Consonni, Nordio, Pravettoni, Cappa and Priori2010; Friesdorf, Conway, and Gawronski Reference Friesdorf, Conway and Gawronski2015). Deontological modes engage affective processes associated with moral conviction (Skitka and Morgan Reference Skitka and Morgan2014), suggesting that women are distinctly sensitive to harm violations encompassed within the care foundation (Friesdorf, Conway, and Gawronski Reference Friesdorf, Conway and Gawronski2015).

Likewise relevant to gender differences is research connecting moral foundations and sociopolitical dispositions, including social dominance orientation (SDO) and right-wing authoritarianism (RWA). Accordingly, the individualizing foundations are negatively associated with SDO, that is, the preference for intergroup hierarchy (Federico et al. Reference Federico, Weber, Ergun and Hunt2013; Pratto et al. Reference Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth and Malle1994). Simultaneously, the binding foundations are positively associated with RWA, that is, the preference for social conformity (Feldman Reference Feldman2003; Federico et al. Reference Federico, Weber, Ergun and Hunt2013). These patterns have been replicated in subsequent research (Milojev et al. Reference Milojev, Osborne, Greaves, Bulbulia, Wilson, Davies, Liu and Sibley2014; Sinn and Hayes Reference Sinn and Hayes2017).

Considered alongside this scholarship, studies that demonstrate gender differences in SDO and RWA suggest corresponding differences in moral foundation reliance. Women have been demonstrated to score lower than men on measures of SDO (Sidanius, Pratto, and Brief Reference Sidanius, Pratto and Brief1995) and authoritarianism (Kemmelmeier Reference Kemmelmeier2010). The lower degree of SDO and authoritarianism among females suggest that, in comparison with men, women are more likely to be concerned with care and fairness and less likely to be concerned with authority and loyalty. These expectations reinforce the previously discussed findings of MFT.

Notably, the literature suggests contradictory expectations regarding the relationship between gender and purity. As highlighted, MFT researchers find a greater reliance on purity among women; however, the literature on gender and authoritarianism suggests that women rely on purity less than men. This contradiction can be helpfully situated in the broader complexities of disgust research, insofar as the emotion of disgust underpins the purity foundation (Landmann and Hess Reference Landmann and Hess2018; Tybur et al. Reference Tybur, Bryan, Lieberman, Hooper and Merriman2011).

The dynamics of socialization, wherein self-reported reactions of disgust conform to gender-related expectations of women’s emotionality and men’s stoicism, may lead to exaggerated inferences regarding gender differences in disgust sensitivity (Balzer and Jacobs Reference Balzer and Jacobs2011). The socialization dynamics which confound disgust research may likewise impact research on gender and purity, potentially contributing to the contradictory record at hand. Consequently, we develop expectations regarding purity rhetoric with caution, and draw primarily from MFT-specific research (Graham et al. Reference Graham, Iyer, Nosek, Haidt, Koleva and Ditto2011).

Here we posit an initial set of hypotheses in which the gender differences in mass moral psychology drive the moral rhetoric of female representatives independent of political party. These hypotheses are as follows:

H1a: Across both the Democratic and Republican Parties, female representatives are more likely to emphasize care, fairness, and purity than male representatives.

H1b: Across both the Democratic and Republican Parties, female representatives are less likely to emphasize authority and loyalty than male representatives.

In reflecting the gender differences demonstrated among the mass public, these hypotheses capture the possibility that moral-psychological patterns influence elite rhetoric over and above partisan-electoral incentives. When it comes to moral rhetoric, individuals tend to craft arguments grounded in their own moral intuitions, even when they are instructed to be persuasive to political opponents (Feinberg and Willer Reference Feinberg and Willer2015). Barring partisan-electoral incentives, we might expect representatives to act similarly and mirror mass gender differences in moral foundations.

Gender in the Democratic and Republican Parties

Second, an alternative set of hypotheses stems from the premise that the Democratic and Republican Parties differ from one another in terms of the political consequences of gender stereotypes. These differences can be traced to how partisans understand their in-party as well as perceptions of issue competence.

The Democratic Party encompasses a broader umbrella of racial and religious groups, whereas the base of the Republican Party is predominantly White and Christian. In open-ended survey responses, Democrats more frequently describe their party as advancing the interests of the party’s constituent subgroups, whereas Republicans more frequently describe their party as advancing an explicitly conservative agenda (Grossman and Hopkins Reference Grossman and Hopkins2015). This asymmetry in partisan self-concept is attributed to the GOP’s demographic homogeneity (Grossman and Hopkins Reference Grossman and Hopkins2015).

The greater emphasis on conservative ideology as a unifying banner for Republican voters presents a challenge for female politicians in the GOP. Gender stereotypes about ideology, in which women are assumed less conservative than men, are widespread (Koch Reference Koch2002; McDermott Reference McDermott1998); however, they are particularly pronounced in the Republican Party and impose a significant disadvantage insofar as perceptions of candidate conservatism drive Republican voter preferences (King and Matland Reference King and Matland2003).

The parties also differ in how gender stereotypes impact perceived issue competence. Republican women gain less benefit than do Democratic women from issue-based stereotypes that associate women with expertise on education and men with expertise on crime (Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009). Compared with Democrats, Republicans are more likely to associate male candidates with competence on crime but less likely to associate female candidates with competence on education (Sanbonmatsu and Dolan Reference Sanbonmatsu and Dolan2009). Insofar as these competencies overlap with partisan issue ownership, wherein the Democratic Party is associated with “compassion” issues and the GOP with “law and order” (Egan Reference Egan2013; Petrocik Reference Petrocik1996), this pattern suggests that gender stereotypes boost the partisan credentials of female Democrats while undermining those of female Republicans.

Given these differences, party affiliation is likely to influence the extent to which female representatives engage in gendered moral rhetoric. For female Democrats, it could be politically strategic to use moral rhetoric invoking the care foundation, insofar as doing so plays into party-gender aligned stereotypes. At the same time, it could be politically costly for female Republicans to emphasize the care foundation, insofar as feminine stereotypes are at odds with the ideological self-concept and issue-orientation of the Republican Party. By extension, female Republicans may benefit from emphasizing the authority foundation, insofar as this moral domain carries stereotypically masculine connotations of leadership. In line with this argument, we examine the following hypotheses:

H2a: Female Democratic representatives are more likely to emphasize care in comparison with male Democratic representatives.

H2b: Female Democratic representatives are less likely to emphasize authority in comparison with male Democratic representatives.

H3a: Female Republican representatives are equally if not less likely to emphasize care in comparison with male Republican representatives.

H3b: Female Republican representatives are equally if not more likely to emphasize authority in comparison with male Republican representatives.

The foregoing hypotheses flow from a theoretical focus on the strategic incentives that female politicians face in a partisan environment. We focus here on the care and authority foundations because these foundations are strongly connected to gender stereotypes of feminine compassion and masculine leadership.

Gender and Race in Elite Moral Rhetoric

Whether examining gender as a party-independent ( H 1a – H 1b ) or a party-conditional ( H 2a – H 3b ) explanatory variable, we recognize that gender is but one source of identity likely to influence patterns of elite moral rhetoric. Racial identity, and the positionality of privilege and marginalization that comes with it in the U.S. context, shapes the strategic motivations of non-White representatives, who may pursue communication styles intended to mitigate racial prejudice and/or mobilize race-specific constituencies (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2012; King-Meadows Reference King-Meadows and Persons2014; Persons Reference Persons1993). In addition, racial identity may alter the political salience of the five moral foundations in a mass psychological sense. Extant research preliminarily supports this implication, insofar as liberal-conservative patterns of moral foundation reliance among Black Americans do not mirror those of White Americans (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Rice, Van Tongeren, Hook, DeBlaere, Worthington and Choe2016).

Indeed, a major shortcoming of the MFT literature stems from an overrepresentation of White participants in experimental samples, which, in turn, obscures our understanding of how race influences moral psychology and its ideological correlates (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Rice, Van Tongeren, Hook, DeBlaere, Worthington and Choe2016). When MFT is analyzed among samples of Black participants, the relationship between conservatism and the binding foundations is weak, which may be attributable to dynamics in religiosity (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Rice, Van Tongeren, Hook, DeBlaere, Worthington and Choe2016). More generally, recent scholarship has challenged the validity of liberal-conservative ideological measurement among Black Americans (Jefferson Reference Jefferson2020), thus further complicating our ability to make inferences from prior research regarding the influence of racial identity on gender patterns in elite moral rhetoric.

Given the complexities and shortcomings of prior scholarship, we stop short of specifying hypotheses with regard to race. However, we include exploratory analysis of race and its interaction with gender insofar as the race-gender intersection shapes elite communication in terms of related dynamics, such as candidate self-presentation (Smooth Reference Smooth2006; Wineinger Reference Wineinger2021).

Data and Methods

To address our theory and hypotheses, we look at the tweets of all members of the U.S. House of Representatives from the 113th Congress to the 116th Congress (2013–21).Footnote 1 An advantage of using social media for the study of moral rhetoric is that politicians increasingly use it to communicate directly with their constituents (Golbeck, Grimes, and Rogers Reference Golbeck, Grimes and Rogers2010; Gulati and Williams Reference Gulati and Williams2013). Twitter is a particularly relevant platform for studying gender insofar as female politicians are especially likely to use it (Wagner, Gainous, and Holman Reference Wagner, Gainous and Holman2017). Additionally, Twitter messages are frequent and distributed in a homogeneous format, which facilitates useful comparisons across and among politicians, over time.

To build our data set, we collected all public tweets from all House members during the 113th CongressFootnote 2 (2013–15), 114th Congress (2015–17), 115th Congress (2017–19), and 116th Congress (2019–21).Footnote 3 These data contain all tweets from the beginning of each congressional session (i.e., January 3) until each congressional session’s midterm election day. Any tweets outside the time period listed here were removed from the data set.

After the tweet data set was cleaned and merged with each MC’s Twitter account biographic information, we then added other member-level demographic variables. Our key independent variables include standard representative-level characteristics such as gender (female/male), party (Democrat/ Republican), ideologyFootnote 4 (–1 to 1), and non-White racial identity (if yes, coded as 1). In addition to these variables, we also include several control measures—a continuous variable controlling for age; and dichotomous variables indicating whether a MC holds a leadership position and whether a MC is in the majority party.

We use a dictionary-based approach to measure the use of moral language in all tweets in our data set. The use of automated textual analysis allows us to analyze congressional communications more comprehensively than hand coding (see Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013). We draw upon the previously validated Moral Foundations Dictionary (MFD; Graham, Haidt, and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009), which contains 11 categories measuring the extent to which a word pertains to one or more of the five moral “foundations.”Footnote 5 Similar to emotional responses, moral intuitions are theoretically appropriate for measurement using dictionary-based methods under the assumption that language can embody various emotions (e.g., Pennebaker, Mayne, and Francis Reference Pennebaker, Mayne and Francis1997) and reflect underlying psychological tendencies (Sterling and Jost Reference Sterling and Jost2018).

Once the dictionary object is constructed, we convert all the tweets in the data set into a text corpus for analysis. Using the R package Quanteda, we apply standard preprocessing steps to clean the data, such as converting all text to lowercase and removing numbers, punctuation, URLs, and conventional English stop words. We then convert the text corpus into a document-feature matrix containing 2.23 million documents (tweet text) and apply the MFD object containing 324 unique unigrams, or single words (359 total). The number of words in each main MFD category is displayed in Table 1. This produced a frequency score for every dictionary category indicating how many words within each tweet are associated with each foundation.

Table 1. Number of Words in Main MFD Categories

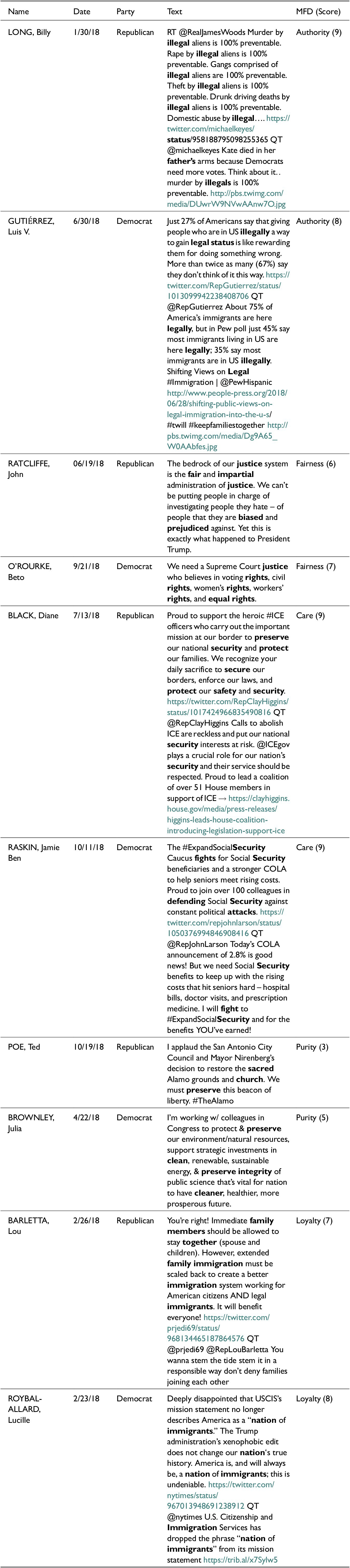

To provide a concrete sense of how foundation-specific moral rhetoric manifests in representatives’ tweets, we present a series of examples in Table 2, including one Democrat and one Republican example per foundation. The examples were selected because they include a high frequency of words from the corresponding foundation in the MFD. For purposes of clarity, the words associated with each foundation in the MFD are given in boldface.

Table 2. Examples of Tweets and Classifications in the MFD.

We will briefly discuss how the tweets reflect the corresponding foundation, beginning with authority. Across each tweet, the representatives incorporate language emphasizing legality. Though both tweets convey different arguments, with the Republican tweet admonishing illegal immigration and the Democrat tweet resisting alleged concerns about providing legal pathways to citizenship, the two tweets convey their messages in the same terms: those of the law. Insofar as the law embodies a sense of authority, these tweets implicitly invoke the moral moorings of the authority foundation.

Moving to the fairness foundation, we can see the tweets invoke the language of justice, fairness, impartiality, and equality. Though emphasizing distinct concerns, with the Republican tweet condemning unfairness in the treatment of former president Donald Trump and the Democrat tweet advocating for fairness vis-à-vis a progressive U.S. Supreme Court, the two tweets pivot on the same rights-based terminology.

Regarding the care foundation, both the Republican and Democrat tweets marshal the language of security, protection, and defending. Though appealing to distinct issues and actors, with the Republican tweet emphasizing harm concerns at the border and the Democrat tweet emphasizing care concerns among Social Security beneficiaries, the terms of each tweet convey an implicit moral orientation around the suffering and safety of those who are vulnerable.

When it comes to the tweets exemplifying the purity foundation, we can see the use of language emphasizing sacredness, preservation, cleanliness, and integrity. While each tweet directs these emphases on distinct objects, with the Republican tweet focused on a historical site and the Democrat tweet focused on the environment, both tweets convey a sense of sanctity at risk of degradation.

Finally, we can see the loyalty foundation invoked across Republican and Democratic tweets through a shared reliance on the terms of immigration. The tweets articulate very different stances on the issue of immigration; however, their repeated use of the term “immigrant” carries an implicit loading of in-group versus out-group and national allegiance, even if marshaled to advance an inclusive message. Though the gist of the Democrat tweet is pro-immigration, it adopts language that implicitly distinguishes people on the basis of a national group identity, putting it on the same field as the Republican tweet with regard to the loyalty foundation.

Table 3 displays the distribution of foundation-specific moral rhetoric in our full congressional tweet data set, containing all public posts (N = 2,229,114 tweets total) from House members in the 113th to 116th Congresses (2013–21). In addition to the number of tweets, the table also shows key summary statistics by gender and party, including the total word count in all the tweets within each subgroup, the total number of moral words used, and the proportion of foundation-specific words (i.e., authority, loyalty, purity, fairness, and care) used relative to the total moral word count. Table 4 displays the number of unique House members in our data set by gender, party, and race/ethnicity, along with the totals for each subgroup.

Table 3. Proportion of foundation-specific moral words in 113th to 116th Congress tweets

* Note: The estimates reported for each foundation represent the proportion of foundation-specific words out of total moral word count for each subgroup.

Table 4. Demographic distribution of aggregated data by gender, party, and race

* Note: This total N represents 1575 unique MC + Congress observations

Results

We estimate multivariate regression models in which the representative, within each Congress, is the unit of analysis. To do this, we first aggregate each MC’s set of tweets by Congress into separate aggregated observations (N= 1,575 total unique MC + Congress combinations). Therefore, MCs serving in more than one Congress have a separate observation for each Congress. This approach helps reduce the level of noise that comes with analyzing a data set of more than 2.22 million rows from 2013 to 2021 and adds greater specification to our measures. More specifically, it allows us to account for differing electoral environments across congressional terms as well as individual-level changes such as ideological shifts.

We examine gender differences in elite moral rhetoric by measuring the emphasis a politician places on a given moral foundation as a proportion of their total moral language. To create our proportional measures of foundation-specific moral language, we first cluster observations (tweets) by each unique MC + Congress observation and then total the raw number of words used by each member from each specific foundation. We divide this raw number for each foundation by the sum of all moral words used across the five moral foundation categoriesFootnote 6 in each MC’s cluster of tweets. Through this process, we calculate for each MC five proportional measures corresponding with each of the five moral foundations.

We use these proportional measures, now re-merged with our demographic data at the member level, as our main dependent variables to examine how female and male representatives differ in their emphasis on the five moral foundations.

For our party-independent hypotheses ( H 1a – H 1b ), we analyze all representatives’ tweets, combining Democrats and Republicans; for our party-conditional hypotheses ( H 2a – H 3b ), we analyze tweet data subset by party, running separate models for Democrats and Republicans.

Gender and Moral Rhetoric

Table 5 displays the results of our multivariate regression models examining H 1a – H 1b , with standard errors (clustered by MC) reported in parentheses below the estimated coefficients. The dependent variables are the proportional measures for each moral foundation. In addition to the control variables and our hypothesized indicators pertaining to gender and party, we also include Congress and state fixed effects in all models. In this section, we report results with and without ideology as a control variable, beginning first with the model excluding ideology.

Table 5. OLS regression of MC average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric (all MCs, by Congress)

Note:

* p<0.1;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

As Table 5 demonstrates, our results are partially consistent with hypotheses H 1a – H 1b . Female representatives are significantly less likely to emphasize authority (1.2 percentage points, p < .01) and loyalty (1.1 percentage points, p < .01) than male representatives, holding party and race constant. In addition, we find that female MCs are significantly more likely to emphasize care than male MCs (1.9 percentage points, p < .01).

Contrary to our expectations, we do not find any statistically meaningful gender differences in the use of fairness or purity rhetoric, suggesting that male and female representatives emphasize these foundations in a comparable manner. Nonetheless, our results reveal gender effects on authority, loyalty, and care rhetoric, which are found independent of theoretically relevant covariates and thus reinforce the unique role gender plays in shaping elite moral rhetoric.

We also find that Republican representatives are significantly more likely than Democrats to emphasize authority (4.2 percentage points, p < .01) and loyalty (3.2 percentage points, p < .01). In contrast, Republicans are less likely to emphasize purity (0.3 percentage points, p < .05), fairness (4.8 percentage points, p < .01), and care (2.3 percentage points, p < .01). With the exception of purity, these results reflect the partisan patterns we would expect given the liberal-conservative differences predicted in MFT.

To further examine the independent effect of gender on moral rhetoric, we control for MC ideology in Table 6.Footnote 7 We find that the effects of gender on authority, loyalty, and care rhetoric persist even when holding ideology constant. By contrast, the independent effect of party becomes less consistent. Given ideological sorting across parties, the results for party and ideology should be interpreted with caution due to concerns about multicollinearity.

Table 6. OLS regression of MC average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric (all MCs, by Congress, w/ ideology)

Note:

* p<0.1;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

Before examining our party-conditional hypotheses ( H 2a – H 3b ), we present Figure 1 to visually explore party and gender differences within the aggregate sample. Figure 1 presents the median proportion of representatives’ foundation-specific rhetoric by party and gender with 95% confidence intervals. The patterns visualized when comparing these median proportions do not account for important variables like ideology and race, and they should be interpreted as a preliminary window into the party-conditional hypotheses tested more thoroughly in subsequent analyses.

Figure 1. Median proportion of foundation-specific language in MC moral rhetoric by party and gender with 95% CI)

The figure illustrates key differences in the rhetoric of Democratic and Republican MCs, which mirror the results of Table 5 and highlight that party identification is important for the moral foundations emphasized by MCs. However, the figure also suggests that our results regarding the effects of gender are largely driven by differences within the Democratic Party. Across all five foundations, Republican women are indistinguishable from their male copartisans, with the closest exception being female Republicans’ slightly greater use of authority rhetoric. Acknowledging that this pattern could be attributable to the relatively small number of female representatives in the GOP, we examine this dynamic further in the next section.

Before turning to those results, it is worth elaborating on the gender differences within the Democratic Party illustrated in Figure 1. Among Democrats, female representatives use more fairness and care rhetoric as well as less authority rhetoric compared with their male counterparts. When it comes to the emphasis placed on loyalty and purity, female Democrats exhibit similarity to their male copartisans.

Party, Gender, and Moral Rhetoric

To examine party-conditional gender differences, we estimate separate multivariate regression models for Democratic and Republican representatives. Table 7 presents our results for the Democratic Party, and Table 8 presents our results for the Republican Party.

Table 7. OLS regression of Democrats’ average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric (all MCs, by Congress)

Note:

* p<0.l

** p<0.05

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

Table 8. OLS regression of Republicans’ average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric (all MCs, by Congress)

Note:

* p<0.l;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

Within the Democratic Party, female representatives emphasize authority (1.4 percentage points, p < .01) and loyalty (1.1 percentage points, p < .05) less than male Democrats. Conversely, female Democrats emphasize care (1.9 percentage points, p < .01) more than their male counterparts. In contrast, female Republicans behave similarly to their male colleagues across all foundations except loyalty, which receives less emphasis by comparison (1.4 percentage points, p < .05).

These results largely mirror differences visualized in Figure 1; however, the points of divergence are telling. For instance, our results in Table 7 suggest a negligible gender effect on fairness and a negative gender effect on loyalty among Democrats, which diverges from the differences (or lack thereof) visualized in Figure 1. These points of divergence suggest the value of accounting for covariates like ideology and race when estimating party-conditional gender effects.

Gender, Race, and Moral Rhetoric

Having reported the results pertinent to our main hypotheses regarding gender and party, we will now discuss exploratory results regarding race and its intersection with gender. In this section, we present additional analyses in Table 9, which introduces an interaction term for gender and race. The results largely reiterate the effect of non-White racial identity demonstrated in Tables 5 and 6.

Table 9. OLS regression of MC average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric (all MCs, by Congress, w/ gender * race interaction term)

Note:

* p<0.l;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

Focusing first on the effects of race, we find that representatives of color emphasize loyalty (2.2 percentage points, p < .01) and fairness (1.7 percentage points, p < .01) more than White representatives. In addition, representatives of color emphasize care (4.2 percentage points, p < .01) less than White representatives. The effect of race on authority and purity rhetoric are statistically negligible.

Turning to the interaction term, we find that female representatives of color emphasize loyalty less (1.7 percentage points, p < .05) than White male representatives. Beyond the use of loyalty rhetoric, we find no further effects for the interaction term of gender and race. The relative lack of statistically significant results from the interaction term may indicate the complexity of intersectional identity and moral rhetoric. Given the underrepresentation of women of color in Congress and the resulting limitations of our data, we interpret our results regarding the interaction term with caution and emphasize the importance of further intersectional analysis (Hancock Reference Hancock2007).

Campaigning versus Governing

To extend our analysis, we examine whether the effect of gender changes as the representative pivots from the focus of governing to that of campaigning. We do so by analyzing subsets of our data set on governing and campaigning periods in Tables 10 and 11. In addition, we formally analyze the interaction of gender and period in Table D.1 of the Supplementary Materials. We discuss both analyses in turn. Governing periods are coded as the first full year of each two-year congressional session (e.g., January 3, 2017, to December 31, 2017), while campaigning periods refer to the latter year of each term leading up to the date of the next election (e.g., January 1, 2018, to November 6, 2018).

Table 10. OLS regression of MC average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric during governing periods (all MCs, by Congress)

Note:

* p<0.1;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01.

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

Table 11. OLS regression of MC average use of foundation-specific language within their moral rhetoric during campaign periods (all MCs, by Congress)

Note:

* p<0.1;

** p<0.05;

*** p<0.01

Models include congress and state fixed effects. SEs are clustered by MC.

In our subsetted analysis of the governing periods, we find that female representatives emphasize loyalty less (1.4 percentage points, p < .01) and care more (1.7 percentage points, p < .01) than male representatives. However, when it comes to authority, purity, and fairness rhetoric during the governing periods, we find no statistically significant differences by gender. In our subsetted analysis of the campaign periods, we find a broader range of gender differences. Here we find that women emphasize authority (1.2 percentage points, p < .01) and loyalty (1.1 percentage points, p < .05) less than their male colleagues when campaigning, and they place greater emphasis on fairness (0.07 percentage points, p < .05) and care (1.7 percentage points, p < .01).

Collectively, these results suggest that the pivot from governing to campaigning may come with an expansion of gender differences in foundation-specific rhetoric. In the governing subset, female representatives only differ from their male colleagues on the loyalty and care foundations. In the campaign subset, female representatives diverge from their male colleagues across all foundations except purity.

Notably, we find that these patterns of gender differences across governing and campaigning are more consistent among Democrats than Republicans. When analyzing the data subsetted on party, we find that female Republicans are similar to male Republicans regardless of whether they are governing or campaigning. By contrast, Democrats evince a broader range of gender differences when campaigning. We report these party-subsetted results in Section C of the Supplementary Materials, and we note here that the gender differences in Tables 10 and 11 may be largely driven by Democrats.

To more robustly analyze this pattern of potential attenuation and amplification of gender differences across governing and campaign periods, we turn to our formal analysis of the interaction term in Table D.1 of the Supplementary Materials. Here, we analyze a variable distinguishing the campaign period as well as an interaction term for gender and campaign period. This analysis uses the full data set including representatives of both parties. Ultimately, the results of this model suggest a more limited scope for the interaction of gender and campaign period. The unique effects of gender persist in the model. However, the effects of campaigning on its own and in interaction with gender are largely negligible. The primary exception includes the positive effect of the interaction on fairness rhetoric (1.1 percentage points, p < .01), suggesting that female representatives use more fairness rhetoric while campaigning than do male representatives while governing. All other results are statistically insignificant, indicating that the effects of gender and campaign-governing period are not conditional on one another.

Taken as a whole, our findings suggest that the overall distinction between governing and campaigning for gender differences in foundation-specific rhetoric is relatively minimal. However, given the exceptional findings for fairness rhetoric, we recommend that future scholarship explore these dynamics further to clarify our understanding of gender-strategic communication during campaign periods.

Robustness Checks

One important concern with our analysis, and the use of dictionary methods more broadly, is that results might be driven by MCs referring to official names of government offices and programs. The use of proper nouns is a decision made by MCs in their political communication to constituents, and different programs may have associated moral loadings that influence public perception (Clifford and Jerit Reference Clifford and Jerit2013). For instance, a tweet about the Department of Defense might imply moral values of care regardless of the rest of the tweet’s content.

If our results are being driven by references to these organizations and programs, it would threaten the validity of our conclusions. To guard against this possibility, we conducted additional analysis on a subset of our corpus excluding tweets that contained words including “department,” “agency,” “administration,” “bureau,” “center,” “division,” “council,” “command,” and “commission.” After manually reviewing a random sample of the excluded tweets, we required a fixed match for “command” to avoid picking up variations such as “commander” and “commanding,” which are fairly common words in political tweets.

A total of 47,066 tweets were found to have at least one word related to governing offices and programs. After these tweets were removed from the data, 2,182,048 tweets remained. We recalculated the foundation-specific proportion measures for each MC using this revised tweet sample. There were the same number of rows/unique MCs in the resulting aggregate data as there were from the full sample (1,575).

Sections B.2.1–B.2.7 in the Supplementary Materials present the results of these robustness checks. In short, the tables illustrate that our main findings are robust to tests where government offices and programs are excluded. These results closely mirror results without excluding these key terms, with female MCs placing less emphasis on authority and loyalty and more emphasis on care than male MCs. These additional tests increase our confidence that our results are not unduly influenced by the organizations and programs being discussed and the use of government offices in public communications by MCs.

Limitations

It is important to note several limitations with dictionary-based approaches. In particular, one might be concerned when a dictionary developed for one purpose is applied to another context—a situation that could cause misleading inferences (Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013; Loughran and McDonald Reference Loughran and McDonald2011). We are less concerned with this possibility given we use a dictionary specifically designed to apply MFT to text analysis by the authors who created the Moral Foundations survey battery, and it has been validated elsewhere (see Graham, Haidt, and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009).

We also run our analyses using a revised but unpublished version of the dictionary to confirm that our results are robust to different moral foundations dictionaries (Frimer et al. Reference Frimer, Haidt, Graham, Dehgani and Boghrati2017). We report these results in Sections B.1.1–B.1.7 of the Supplementary Materials and show that our findings are largely consistent with this alternative specification.

In addition, our study is limited in its ability to disentangle the use of moral rhetoric by representatives from the issue content of their communications. Political issues are commonly referred to using words which belong to the MFD. Nonetheless, representatives have a choice over how they invoke issue domains. For instance, the choice between the language of marriage equality versus defense of marriage is a moral-rhetorical decision made by the speaker.

Extant research further indicates the interconnectedness of issues and morality. Politicians’ issue stances lead to moral attributions (Clifford Reference Clifford2014), and even issue domains generally considered “nonmoral” engender moralized processes of attitude formation (Ryan Reference Ryan2014). Given the “far-reaching force” of morality over political issues (Ryan Reference Ryan2014, 381)—as well as the current absence (to our knowledge) of a publicly available and validated issue-dictionary, capable of facilitating automated text analyses of large longitudinal data sets, without requiring some level of supervised learning to ensure the measures meet acceptable performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision, and recall)—we leave it to future research to more thoroughly examine how gender differences in elite moral rhetoric map onto gender differences in issue content. Doing so may require the use of latent dirichlet allocation topic modeling and/or in-depth qualitative analyses, which are beyond the scope of this study.

Summary

Taken together, our results demonstrate that gender appears to be a critical factor in the moral values espoused by MCs in their public communication. While controlling for alternative explanations, we find that female representatives are more likely to emphasize care and less likely to emphasize authority and loyalty than their male peers. However, when subsetting by party, we find that gender effects are most pronounced among Democrats and relatively negligible among Republicans. While these results by party largely meet our expectations, there are some results that present exciting areas for future research. In particular, exploring how race and ethnicity shape elite moral rhetoric is an important area for future scholarship, especially given our findings suggesting that MCs of color emphasize fairness and loyalty more than White MCs, but espouse care less frequently.

Furthermore, we find limited evidence for the influence of campaign-governing periods over gender differences in moral rhetoric, with fairness being the only foundation for which the interaction of gender and period yields a statistically significant difference. Finally, additional robustness checks indicate that our results are not overly influenced by the use of proper nouns associated with government departments and programs, and that the results hold up across multiple MF dictionaries. While we find evidence of both party-independent and party-conditional differences by gender in elite moral rhetoric, there is plenty of scope for further work to explore how identity shapes public messaging by elected representatives.

Discussion

Across the model specifications and subsetted analyses, we paint an increasingly nuanced picture regarding the influence of gender over elite moral rhetoric. Where we do find gender differences—primarily among Democratic representatives—we find that these gender differences are compatible with both strategic motivations (insofar as Democrats benefit from feminine stereotypes) and mass moral psychology (insofar as female representatives emphasize care more and authority and loyalty less).

Notably, the relative absence of gender differences in moral rhetoric among Republican representatives is likewise compatible with strategic motivations. In pursuit of political support, female Republicans face the challenge of countering the public’s implicit association of femininity with the Democratic Party. Furthermore, female Republicans face the additional challenge of navigating attitudes held among their copartisan base that associate masculinity with conservative credentials. Considering these challenges, and considering the stereotypes which associate gender with qualities that map closely onto the care and authority foundations (i.e., compassion and leadership), it is perhaps unsurprising that we see minimal gender differences on these specific foundations as well as those with less established gender-stereotypic loadings (i.e., fairness and purity), with loyalty the only point of difference. Mirroring the moral rhetoric of male Republicans may offer a strategic means for navigating gender stereotypes which carry distinct costs for female Republicans.

Overall, our study builds upon prior scholarship emphasizing the strategic navigation of gender stereotypes among female politicians through their public communication. It brings this scholarship into conversation with literature on gender differences in moral psychology by employing the framework of MFT, which allows for a more fine-grained analysis of differences in elite moral rhetoric. In doing so, it offers clarity regarding how moral rhetoric is used to avoid or embrace gender stereotypes while also highlighting dimensions of morality in which gender stereotypes ought to be studied more thoroughly. Given the lower frequency of loyalty rhetoric among female representatives in the aggregate sample as well as the party subsets, we suggest future research examine the relationship between gender and the loyalty foundation in greater depth, from the perspective of gender stereotypes as well as mass psychology.

Interestingly, we find few traces of gender difference regarding the use of fairness and purity rhetoric in our regression analyses. We only find meaningful differences for fairness rhetoric when analyzing the campaigning subset as well as the formal interaction of gender and campaign period, suggesting that gender-strategic objectives specific to campaigning may uniquely amplify the use of fairness rhetoric among female representatives. Across all analyses, we find no gender differences when it comes to the use of purity rhetoric. This could be because purity is not commonly invoked in explicit terms (Clifford and Jerit Reference Clifford and Jerit2013), or because purity rhetoric is polarizing and potentially unpersuasive (Gadarian and van der Vort Reference Gadarian and van der Vort2018). Given the contradictory implications of extant research on purity morality (as discussed earlier), the nonsignificance of gender is ultimately unsurprising and reflects the need for further research.

Furthermore, the finding that Democrats are more likely to emphasize purity than Republicans defies the theoretical expectations of MFT.Footnote 8 These findings with regard to purity rhetoric and partisanship suggest an avenue for further research. The low frequency with which purity language was used across our text corpus overall is interesting in its own right. Future research should examine how the language included in the purity category translates to explicitly political platforms and, more specifically, in social media posts. Qualitative analysis of the contextualized usage of purity rhetoric may further illuminate the nature of gender and partisan differences in purity language.

To further clarify our results, future research should examine how a representative’s gender identity shapes the public’s response to their use of rhetoric invoking the fairness and purity foundations, as well as the other foundations of authority, loyalty, and care. Understanding how foundation-specific rhetoric impacts voter preferences would help explain our analysis of gender differences during campaign and governing periods.

In addition, future research should more robustly investigate how gender shapes the public’s reliance on the foundations in their own political reasoning. Such research would further clarify how the gender dynamics demonstrated here relate to the strategic motivations of partisan representatives as well as the mass psychological patterns of moral foundation reliance.

Further, our study also reveals notable racial differences in moral emphasis among congressional representatives, with non-White representatives emphasizing the loyalty and fairness foundations more and the care foundation less than their White counterparts. Given these results, future research should examine more robustly how racial identity may shape gender differences in moral rhetoric.

More broadly, MFT scholarship should consider how engagement with the five moral foundations, at the levels of both public opinion as well as elite rhetoric, may be shaped by racial privilege and marginalization. Scholarship should continue assessing the cross-cultural generalizability of MFT (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Rice, Van Tongeren, Hook, DeBlaere, Worthington and Choe2016), and should consider how different identities may imbue the moral foundations with nuanced sensibilities. For instance, intersections of gender, race, and class may yield a moral orientation toward care that is social and political rather than interpersonal in function (Graham Reference Graham2007) and that is more emancipatory, spiritual, and community oriented in substance (Collins Reference Collins2000). Exploring the differences in function and substance that may mark interacting sensibilities of race, class, and gender across all five foundations could provide insight into how congressional diversity may impact patterns of elite moral rhetoric.

Conclusion

This study builds upon prior research examining gender and party differences in elite rhetoric. Our use of the MFT framework heeds the moral nuances of political communication, and our attention to multiple sources of identity may explain our documentation of MFT-consistent partisan differences in moral rhetoric, which have been elusive in extant research (Neiman et al. Reference Neiman, Gonzalez, Wilkinson, Smith and Hibbing2015). That said, partisan differences become less consistent in our analysis once ideology is controlled for, suggesting a need for further investigation regarding dynamics of party and ideology.

Our analysis essentially offers a bird’s-eye view, establishing the broad coordinates of gender differences in elite moral rhetoric. The importance of digging deeper to appreciate the subtleties of moral discourse, which may differentiate the meanings of moral language at different intersections of identity, cannot be understated. Nonetheless, our study reveals the imprint of gender stereotype navigation and gendered moral psychology on the rhetoric of those in power. Our study illustrates the value of integrating across a range of literatures when developing expectations and interpreting results so as to heed the influence of both strategic motivations and mass moral psychology. Considering the pressures of partisan-electoral incentives alongside differences of moral-psychological perspective offers an expansive theoretical framework for investigating the rhetorical dimension of female political leadership. Applying this approach to a broader range of intersecting identities remains a promising research agenda worthy of further pursuit.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X2200023X.