1. Introduction

The only sibilant in the phonemic inventory of Finnish is the fricative /s/, standardly described as a voiceless alveolar laminal fricative. The /s/ of Finnish has been described as varying in coarticulation with the surrounding sounds or along the individual structure of the vocal tract (Suomi et al. Reference Suomi, Toivanen and Ylitalo2008:35, Iivonen Reference Iivonen, de Silva and Ullakonoja2009:57). The status of the /s/ being the only sibilant enables relatively free variation, and the variants distinct from the norm may gain other social meanings. Similar tendencies for /s/ variation to gain social meaning are known in many languages and speech communities (Levon, Maegaard & Pharao Reference Levon, Maegaard and Pharao2017; see also Section 2).

In the context of contemporary Finland and Finnish, perceptions regarding the variation of /s/ are loaded with ideology. Our previous work (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020) has documented how there is an ideological link between (basically any) deviant or socially meaningful /s/ pronunciation and the place Helsinki. The variants deviant from the norm, and typically the one(s) heard as ‘sharp’, ‘fronted’, or ‘hissing’, are perceptually connected to Helsinki, or particular styles primarily associated with Helsinki (see also Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2002, Palander Reference Palander2007, Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015). While there is some research-informed evidence that fronted variants can be heard in other regions too, at least in Turku (Aittokallio Reference Aittokallio2002), thus far there has only been one preliminary study on the variation of /s/ in production in the Helsinki area (Koivisto Reference Koivisto2022). This study, despite lacking comparison to other areas, does not provide much support for the expectation that the /s/ pronunciation of occasional speakers from Helsinki would differ from those of other regions.

Our studies so far (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020) have indicated how the contemporary social meanings of /s/ variation among Finns have their historical roots in the concerns of nation building and Finnish language norm-building processes at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Finland. The present study continues from our previous work by exploring how the educational system in the course of the twentieth century has contributed to the norm of ‘proper /s/’ in Finnish society. Addressing the educational aspect, the analysis will provide additional transparency on the enregisterment process of ‘Helsinki s’, which may not be classified as an official linguistic fact but has for a long time been prominent as a ‘folk linguistic fact’ (see Agha Reference Agha2003 and Niedzielski & Preston Reference Niedzielski and Preston2003 for the theoretical underpinnings). The present case is also an example of the power of education in processes of enregisterment of a linguistic item or ways of speaking (Agha Reference Agha2003, Johnstone Reference Johnstone2016).

In the next section, the empirical and theoretical background of the study is introduced in more detail, followed by a description of the methodological framework in Section 3. Section 4 presents the first part of the analysis by focusing on the institutional landmarks that have supported the instruction of ‘proper speech’ within Finnish society. Our analysis in Section 5 focuses on the key educational materials and resources designed for national education and transmission of norms, enhancing proper /s/ pronunciation among them. Section 5 also briefly reviews the more recent shift in the educational ideology of /s/, in the light of media documentations and available research findings.

2. Empirical and theoretical background

As reviewed in Levon, Maegaard & Pharao (Reference Levon, Maegaard and Pharao2017), interesting similarities across cultural and linguistic contexts have been discovered in how variation in /s/ production is perceived in terms of social meaning potentials. Studies carried out in different language communities have indicated that the fronter place of articulation of /s/ is associated with certain types of femininity or male gayness, as in American English (Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2011), in Hungarian (Rácz & Shepácz Reference Rácz and Shepácz2013), in Danish (Pharao, Maegaard, Møller & Kristiansen Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Spindler Møller and Kristiansen2014), and in British English (Levon Reference Levon2014). In the Finnish context, similar findings have been reported in studies based on different types of perception and imitation tasks (Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2013, Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015, Vaattovaara, Kunnas & Saviniemi Reference Vaattovaara, Kunnas, Saviniemi, Brunni, Kunnas, Palviainen and Sivonen2018) and interview and media performance data (Surkka Reference Surkka2022). A number of traditional folk linguistic studies in the Finnish context, however, have implied that at the same time, the social meaning potentials of the fronted variant of /s/ tend to be primarily associated with place, specifically Helsinki (e.g. Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2002, Palander Reference Palander2007, Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2013, Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015).

Our research interests concerning the perceptual landscape of /s/ variation originates from an initial interest in understanding why Finnish people generally seem to take for granted that such a phenomenon as ‘Helsinki s’ exists, while it has not been identified as a linguistic fact by linguists. The first perceptual research settings (reported in Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2012, Reference Vaattovaara2013, Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015) were informed by the post-structuralist view of places as socially constructed spaces and processes (e.g. Johnstone Reference Johnstone and Fought2004, Reference Johnstone, Mesthrie and Wolfram2011, Massey Reference Massey2005, Gal Reference Gal, Auer and Erich Schmidt2010). This was done due to the strong perceptual link to place, less typical of many other language communities, and also the indirect link to underlying, more dynamic associations to certain (urban) styles (‘city-s’, ‘pissis-s’; Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2013; cf. Valley girl style, Eckert Reference Eckert2008) implied in earlier folk linguistic studies. Building on the late-modern understanding of language as a semiotic system, and places and varieties as imagined constructs (Eckert Reference Eckert2008, Johnstone Reference Johnstone, Mesthrie and Wolfram2011), it was possible to gain an understanding of how such a folk linguistic fact as the ‘Helsinki s’ need not even have a specific acoustic correlate in order to become ‘real’ for the language community (see Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017). Using exploratory qualitative methodology with the theoretical understanding of places and varieties as imagined constructions enabled the investigation of language users’ more in-depth reflections and reactions disconnected from the dialectological approach to space (see Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2012 and Reference Vaattovaara2013 for this discussion). The participants of our listening and reaction tasks covered a number of regions, social backgrounds, and generations.

Among the main findings based on the first studies was that the notion ‘Helsinki s’ is a widely shared construct that is taken for granted to the extent that, regardless of the phonetic quality of a speaker’s /s/, the sound tends to be perceived or commented on as ‘Helsinki s’ as long as the speaker is perceived, on the basis of whichever linguistic and/or stylistic cue(s), to be of Helsinki origin. The fact that a number of acoustic realisations of /s/ were often associated with Helsinki(ness) encouraged further studies in a multidisciplinary research group consisting of linguists and a historian to explore the enregisterment of the ‘Helsinki s’ from the sociohistorical point of view.

Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen & Vaattovaara (Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020) have documented how the variation of /s/ pronunciation started to gain social recognition in Finland in the sociopolitical situation of the late nineteenth century. The issue of /s/ pronunciation, among many other normative concerns, came to manifest nation building and norms of ‘good Finnish’ in the late nineteenth century. Against the nationalistic agenda, Helsinki as an industrialising and multilingual, rapidly growing modern city was regarded as a stain on the national story. Helsinki gained reputation as a ‘sinful’ place where norms of proper Finnish were violated in this still dominantly Swedish-speaking city. Helsinki differed in every way from the ‘pure’ rural culture and areas with ‘pure’ dialects, with the local slang developing based on multilingual exchanges (see Lehtonen & Paunonen Reference Lehtonen, Paunonen, Kerswill and Wiese2022). At the time, Finland had achieved autonomy under Russian rule (1809–1917), following the long-term Swedish rule that ended in 1809.

The spirit of the era of nineteenth-century nationalism is summarised in the slogan Ruotsalaisia emme ole, venäläisiksi emme tahdo tulla, olkaamme siis suomalaisia (‘Swedish we are not, Russians we do not want to become, let us be Finns’). According to Marjanen (Reference Marjanen2020:167–168), the slogan was circulated in slightly different forms, sometimes highlighting that we are no longer Swedes. The origins of the development of the construct of ‘Helsinki s’ dates back to this era, the late-nineteenth-century historical and language-political situation in Finland, when Helsinki was still a predominantly Swedish-speaking, rapidly growing city. The voluntary shift from Swedish to Finnish by the Swedish-speaking elite played a historically important role in the process of construction of the Finnish nation (see Huumo et al. Reference Huumo, Laitinen and Paloposki2004, Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017).

In the context of a Swedish-speaking majority, the influence of Swedish was a particular concern and considered as the main threat to proper Finnish. Finnish was a target of verbal hygiene (Cameron Reference Cameron1995), even hyperstandardisation, a highly mediatised linguistic standardisation extending to unnecessary details (see Cameron Reference Cameron1995:47, Jaspers & Van Hoof Reference Jaspers and van Hoof2013). In the nationalistic agenda, variability of pronunciation did not serve to construct the nation of Finland and the distinctiveness of Finnish. The normative tensions are documented and discussed in more detail in Halonen et al. (Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020; see also Lehtonen & Paunonen Reference Lehtonen, Paunonen, Kerswill and Wiese2022). Overall the studies so far show how this process has been intertwined with standardisation and purism, described as a megatrend of ideology of linguistic correctness by Nevalainen (Reference Nevalainen2015) and Culpeper & Nevala (Reference Culpeper, Nevala, Nevalainen and Closs Traugott2012:383).

It is important to point out that neither the academic nor the public discourses have explicitly used the terms standard and non-standard in relation to /s/ variation. This presumably comes down to the coarticulatory nature of the variability of the sound, but also to the fact that the standard language of Finnish does not draw on any one variety or social class but is a composite of various dialects. It is also good to note that the current research setting has been motivated by the fact that the issue of /s/ pronunciation has been the subject of public discussion throughout the past 120 years. ‘Helsinki s’ as a deviation from the normative /s/ has been circulated by the media ever since the early twentieth century, and the contemporary twenty-first-century Finnish mass media still contributes to this ideology. The present analysis will provide some more insights into how this has happened, with support from and in dialogue with the educational system.

3. Data and methodology

As Blommaert (Reference Blommaert2010:4) has noted, research addressing language ideologies in historical texts also requires historical analysis. The present study, as described above, draws on our previous research dealing with the enregisterment of the ideological construct of ‘Helsinki s’. We regard this research as a contribution to historical (socio)linguistics and (socio)historical linguistics (see e.g. Blommaert Reference Blommaert2010:125–130, Nevalainen & Rutten Reference Nevalainen and Rutten2012, Nevalainen Reference Nevalainen2015). Similarly to our previous studies addressing the enregisterment process, we have used sociohistorical and discursive approaches to study the macro-level of a society’s history and micro-level textual data sets of educational materials in order to investigate the educational transmission of the /s/ norm, which is still observable in the contemporary ideological climate and the social meaning potentials of /s/ variation, as indicated along with the analysis.

As we continue the study of a relatively long historical trajectory and continuum of the ideological climate of /s/ pronunciation, we continue to use eclectic elective research data and approaches (see Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020). In the previous studies on the enregisterment of ‘Helsinki s’, we used a variety of accessible written materials, consisting of, for example, early linguistic studies of Finnish, descriptions of Finnish phonetics in grammars, and various other types of historical data and texts, such as theatre reviews, columns, opinion pieces both in mass print media and on social media, as well as minutes of the meetings of Kotikielen Seura (the Society for the Study of Finnish), which has played a large role in language-political discussion since its founding in 1876.

For the study reported in this article, we have used our previous findings for directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon Reference Hsieh and Shannon2005:1281), in which existing research or theory can help focus the research question. The earlier work led us to the present resources, the educational development history (Section 4), and the key educational materials (Section 5). After a brief historical account (in Section 5.1), the materials examined cover the most widely used guidebooks from the early 1900s to the 1970s, giving prescriptions on the pronunciation of /s/ (Section 5.2). Some related audio resources, such as radio programmes connected to the print materials, are included in the analysis (Section 5.3). Along with the analysis, we make connections to a variety of historical and contemporary resources, particularly media resources, in order to contextualise and interpret the present findings concerned with the educational development and materials dealing with the /s/.

4. Institutional landmarks in the instruction of proper Finnish

The normative transmission of ‘good speech’ and ‘proper pronunciation’ of Finnish can be traced by following at least three educational development paths. One of these is the growing resource of actual materials during the 1900s (dealt with in Section 5) with a focus on /s/ pronunciation prescriptions. In institutional terms, the historical account uncovers two cornerstones: the founding of the first professorship of Finnish language in 1851 at the dawn of nationalism, and later, in the early 1900s, the founding of the speech sciences and the first university teaching positions in this area. The founding of logopaedics (1947) and the Finnish Association of Speech Therapists (1966) took place later.

The first Finnish language professorship was founded at the University of Helsinki. The first holder of the position, Matthias Alexander Castrén, was an ethnologist and a pioneer in the study of the Uralic languages. His interests were in the investigation of the kinship between Finnish and several other languages (Suutari & Salo Reference Suutari and Salo2001:16). Castrén’s career as a professor was cut short after only one year (1851–1852) due to his early death. Castrén’s first successors, Elias Lönnrot (1853–1862), August Ahlqvist (1863–1888), and Emil Nestor Setälä (1893–1929) had a great interest and role in the standardisation of Finnish in the context of the normative, puristic climate shown in the analysis in Section 5, where we focus on the /s/ pronunciation.

In our previous documentation (Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020) we report in more detail on how the power of the early professors facilitated the normative climate in academia and beyond. Ahlqvist, in particular, had a strictly puristic agenda based on the ideology of ‘correct vs. incorrect’ use of language, and his efforts in resistance of both dialectal and Swedish influence in the formation of norms of Finnish is well known (Paunonen Reference Paunonen1996). Setälä’s approach was more moderate, based on the principle of appropriateness, as he proposed the idea of following the model of the most respected authors rather than language authorities (Setälä 1921 [Reference Setälä1893]:91). What deserves attention here is that whereas Setälä’s academic and political power became well known (Karlsson Reference Karlsson2000, Kelomäki Reference Kelomäki2009), out of all his scientific arguments, which were generally accepted in academic society more or less uncritically, his approach to norms was not among them: strict purism overruled Setälä’s view. This is worth mentioning, as historical analyses of Fennistics (Paunonen Reference Paunonen1996, Karlsson Reference Karlsson2000, Kelomäki Reference Kelomäki2009) have documented that Setälä was an exceptionally strong authority in Finnish linguistics. It seems that the puristic agenda proposed by Ahlqvist and others was even stronger.

According to Keskinen (Reference Keskinen1998:54), speech education was very marginal in Finland until the early 1900s. In the founding of the first speech teaching positions both for Finnish and Swedish in 1910, Setälä’s role as a professor of Finnish was notable. The model for speech education was taken from Germany, from where Setälä had adopted Neogrammarian theory, which was dominant in Finnish linguistics for decades (Setälä 1921 [Reference Setälä1893], Kelomäki Reference Kelomäki2009). In the decades to come, many linguists and teachers took part in academic and professional discussions concerning the importance of teaching exact, proper, clear, beautiful, or standard pronunciation of Finnish (e.g. Lähteenmäki Reference Lähteenmäki1908, Santalahti Reference Santalahti1908, Tarkiainen Reference Tarkiainen1913a, Reference Tarkiainen1913b, Marjanen Reference Marjanen1937).

It would be a simplification to claim that the ideological and institutional development described here would be a result only of the rise of nineteenth-century nationalism, but the political context did lay the foundations for the language-ideological atmosphere in which the norms of Finnish were developed (Huumo et al. Reference Huumo, Laitinen and Paloposki2004, Nordlund Reference Nordlund2004). The stance was indeed puristic, emerging from the national romantic idea of the bond between language and nation (Thomas Reference Thomas1991, Nordlund Reference Nordlund2004). It is easy to see why it became of such importance to keep Finnish language clean from any non-Finnic influence, but particularly from Swedish influence (see Section 2). As noted above, this was a particular mission of professor Ahlqvist, but also his follower E. A. Saarimaa, whose guidebooks with a strict tone were to become widespread in the Finnish language community. We will return to this in Section 5.

Following the founding of the first position for speech disorder specialisation in 1943, the field of logopaedics was founded at the University of Helsinki in 1947, and also the Finnish Institute of Speech Communication in that same year. These two institutions played a key role in educating teachers, and in providing teaching materials for schools and other educational purposes. It took a while for the education of speech therapists to start as a more systematic and nationwide practice, but the 1960s has been described as the breakthrough decade of the speech therapy praxis in Finland (Remes et al. Reference Remes and Hyvärinen1987, Sellman & Tykkyläinen Reference Sellman and Tykkyläinen2017:25). After the founding of the Finnish Association of Speech Therapists, the more systematic speech therapy in Finnish schools started to become institutionalised. For the first two decades, a disorder-centred and normative approach was at the heart of speech therapy practice, before the more pragmatic and interaction-oriented approach began to take hold in the 1980s (Sellman & Tykkyläinen Reference Sellman and Tykkyläinen2017), and this is why we delimit the current analysis to the 1970s. The relatively slow shift with respect to /s/ pronunciation will be briefly addressed in Section 5 and in the Discussion, Section 6.

The origins of speech therapy practice hardly stemmed from the puristic language ideology as such but from more medical concerns, such as rehabilitation of the deaf, treatment of stuttering, and correction of actual speech defects. However, during the early decades of the twentieth century and the development of speech therapy practice in schools, the language-ideological atmosphere seems to have been favourable for substantial correction of /s/ pronunciation – not only in terms of clearly articulatory problems (such as lisp), but also in terms of correcting any /s/ pronunciation deviant from the norm, in particular the Swedish-like ‘fronted’ or ‘sharp’ variant.

5. Educational materials for enhancing proper /s/ pronunciation

5.1 Historical /s/ discourses in brief

For us that kind of [French-like sophisticated] pronunciation is a national impossibility. A Finn is a monotonous talker and perhaps likely to remain so. (Tarkiainen, Reference Tarkiainen1913a:93; translation by the authors)

By the time the first school curriculum with educational goals was designed in 1925 (Launonen Reference Launonen2000), there was already strong agreement on the normative pronunciation of /s/ in Finnish. Discussed among academics (the citation above from Tarkiainen Reference Tarkiainen1913a is an example), the central aims of the pronunciation norm in general were to avoid, on one hand, the coarseness of the uneducatedness of regional dialects, and, on the other hand, the ‘artificial prissiness’ of the Swedish influence. As explicitly addressed by Tarkiainen (Reference Tarkiainen1913a), who had a role as a speech educator at the Finnish Theatre during 1905–1909, this was regarded as a non-Finnic characteristic. This principle did not concern /s/ pronunciation alone, but, in the materials explored, this exact characterisation particularly concerned the Swedish-sounding fronted /s/ pronunciation.

According to our explorations of historical documents, the judgement of Swedish-sounding /s/ as ‘artificial and prissy’ may have originated from the meeting of the Society for the Study of Finnish in March 1885. The society was founded in 1876 to cherish and develop norms of Finnish, with Ahlqvist in the lead. A few years before this, in 1873, the Finnish Theatre was also founded. The theatre was regarded as playing an institutional role as a linguistic model for proper Finnish (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017:1176, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020:89, 158). However, the unsatisfactory language of the theatre performers had triggered attention from the start, as evidenced for example in a review in the newspaper Uusi Suometar (5 May 1873). The problem was that the performing artists were mainly L1 speakers of Swedish, and learners of Finnish, unable to meet the requirements of proper Finnish language.

In March 1885, the members of the Society for the Study of Finnish had again visited the Finnish Theatre. According to the minutes of the meeting immediately afterwards, E. N. Setälä, the vice-head of the Society at the time, noted among other critical issues that ‘the sharp fronted Swedish s, articulated by several female actresses, sounds artificial and prissy’ (originally noted in Paunonen Reference Paunonen1976:337). This observation concerning the language of the female actresses was not the only critical one, but, apparently among the most notorious and far-reaching ones. The general public were exposed to these judgements and discourses via theatre reviews in the local media, as during its early years the Finnish Theatre performed not only in its theatre house in Helsinki but also in tours throughout the country (Paavolainen Reference Paavolainen2016).

While the media has played a crucial role in circulating the idea of ‘Helsinki s’ in the twenty-first century (Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020), the power of the media in the process of the enregisterment of this contemporary ideological construct was already present in much earlier times. The roots in the public judgements of the ‘bad language of Helsinki residents’ originate from late-nineteenth-century newspapers such as Sawo-Karjala and Wiipurin Sanomat, from the theatre reviews and other writings reporting on the urban life of Helsinki. The media, therefore, already in the late nineteenth century, contributed to the lay understanding of ‘Helsinki s’. The earliest mention of this concept that we have been able to find is in Kansan lehti (‘Folk magazine’) of 6 February 1906 pointing out that ‘the genuine Helsinki “ässä” hissed in almost every female actor’s mouth’. The formulation implies that already at that time, ‘Helsinki s’ was a phenomenon that was taken for granted, and iconic of performing female artists of the rapidly growing city of Helsinki, perceived as sinful (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020).

Interestingly, the performers’ /s/ – described as ‘artificial and prissy’ in the meeting of the Society for the Study of Finnish – was not only repeated for quite some time in academic discussions (see e.g. Tarkiainen Reference Tarkiainen1913a) but also transmitted to learning materials used in schools and other educational contexts. In the next section, we will first focus on the findings of educational books (Section 5.2) and then turn to other relevant educational resources in audio format (Section 5.3).

5.2 Guidebooks for schools and for other educational contexts

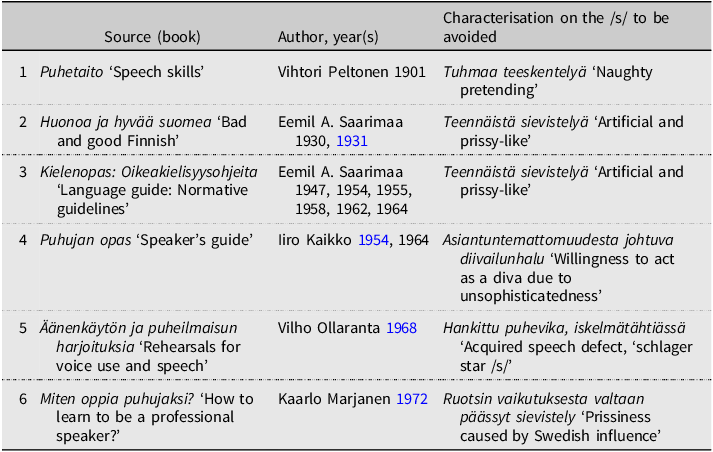

Investigation of the six most widely used educational materials from the 1900s to the 1970s (see Table 1) indicates that Setälä’s characterisation of fronted /s/ pronunciation in Finnish as ‘artificial and prissy’ is echoed and implied, if not repeated word for word, in the educational materials published during the early twentieth century and even as late as the 1970s when speech therapy practice in schools had become institutionalised (see Section 4).

Table 1. The most notable and widespread guidebooks published from the 1900s to the 1970s on the characterisation of non-normative (fronted, sharp) /s/ in Finnish

Among the key materials educating Finns in /s/ pronunciation were E. A. Saarimaa’s guidebooks (books 2 and 3 in Table 1). Huonoa ja hyvää suomea (‘Bad and good Finnish’) was first published in 1930 (2nd edn 1931). The book was based on Saarimaa’s radio presentations and writings about Finnish norms in the Virittäjä journal (founded in 1897). In both editions, the ‘sharp [fronted] s’ is listed at the top under the section Ääntämysvirheitä (‘Mispronunciations’) as ‘artificial and prissy-like’, with a straightforward note that ‘that’s what it often really is’ (sellaista se usein kai onkin; Saarimaa Reference Saarimaa1931:5). Later, Saarimaa’s language guide Kielenopas, of which six editions were published during 1947–1964, repeated the same characterisation of /s/ mispronunciation throughout every edition.

Although Saarimaa’s guidebooks alone could have had a great influence on Finns’ understanding on what is and what is not proper pronunciation of /s/, there were a number of other materials that also contributed to this ideology, the most widespread ones listed in Table 1. Even before the founding of teaching positions in the speech sciences, Vihtori Peltonen’s guidebook on speech skills (1901) represented the same discourse, referring to some of the /s/ pronunciation problems as ‘naughty pretending’. According to Kaarlo Marjanen (Reference Marjanen1937:385), Peltonen ‘had received help’ from several representatives of the Society for the study of Finnish. While Peltonen’s book, as indicated in its preface, was intended for ‘homes and schools to cherish the national language and national success more generally’, many more similarly oriented publications appeared in the years to come along with the institutionalisation of the speech sciences and speech therapy practice.

A closer look at the educational materials produced by speech science professionals provides more insights into the development of the ideological construct of ‘Helsinki s’, which, again, has kept this sound in the spotlight from generation to generation. The cyclic development is observable in the shift in discourse from the earliest materials (sources 1–3) to later ones (sources 4–6). In the books and their editions published from the 1900s to the 1970s (see Table 1), we can see how the ‘too fronted s’ is first pointed out as an index of (naughty) ‘prissiness’ (sources 1–3). In the materials published during the 1950s and 1960s (sources 4–5), the justification is extended to ‘unsophisticatedness’ and explicit reference to ‘schlager stars’. As late as 1972, Marjanen (source 6) points to the causal effect of the phenomenon of too fronted /s/ being caused by prissiness and coming down to Swedish influence.

In the light of the present educational material data and the documentation more thoroughly examined in our previous studies, it is easy to see how the perceived ‘Swedishness’ first gained an index of ‘prissiness’. The first index, ‘Swedish influence’, simply captured the transfer of Swedish /s/ pronunciation into Finnish of the early upper-class language switchers, Swedish-speaking Fennomans, in the mid-nineteenth century. As discussed above, the previously Swedish-speaking elite, such as scholars, civil servants, or higher-ranking soldiers – as well as Swedish-speaking actresses – shifted their language officially from Swedish to Finnish in alignment with the nationalistic agenda, struggling to pronounce the normative Finnish /s/. Perhaps not surprisingly, then, it was the female performing professionals, who were positioned as language models, and who in the public eye were blamed for their wrong, non-normative Swedish /s/.

Sources 4–6 seem to reflect the cultural change rising in the 1950s in the form of popular culture and schlager stars. The leading Finnish female schlager stars were Laila Kinnunen, Brita Koivunen, and later Marion Rung, who all happened to be L1 Swedish speakers.Footnote 1 They were ‘divas’ and popular especially among the youth, with their notably fronted (Swedish) /s/, which now started to gain ‘stardust’ (see Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020:228–245).

During the decades to come, this ideological link was to strengthen along with the popularity of pop stars and other popular culture personae, but the stardust was already in the air in Marjanen’s note on Swedishness. It is not clear exactly which cultural phenomenon Marjanen is implying with his note on the Swedish influence, but it can be presumed that it was motivated by the contemporary bilingual L1 Swedish-speaking schlager stars. This phenomenon was overtly addressed in Ollaranta’s book published a few years earlier in 1968 (source 5). Perhaps best illustrated in an anecdote presented in Ollaranta’s book, it is evident that the schlager star phenomenon turned out to be a major counterforce to the /s/ norm education with its (originally) nationalistic and puristic agenda, visible also in the most recent of the guidebooks we have analysed (sources 5–6 in Table 1). Ollaranta (Reference Ollaranta1968:62) writes (translated from Finnish by the authors):

For the spread of this kind of s in our speech we can ‘thank’ the public media, radio and television and the record companies. Here is one example: a few years ago the author had an energetic and lively boy called Jari, from the second grade of primary school, as an s-patient. The curing of his s went well and his pronunciation started to be flawless, but I recommended him to come to a speech therapy session for a check-up after the school holiday. After the holiday week Jari came to see me. From his very first words as he arrived, I noticed that something had happened to his s: the hissing pronunciation was even worse than before. I asked him: ‘Oh what has happened, your pronunciation was going so well?’ After thinking about my words for a minute, he replied: ‘Well, you know, it may be that during the winter holiday there was the Eurovision Song Contest pre-competition on the tele, and I watched it every night.’ (This is a true story.)

The fact that the fronted variant of /s/ was originally directly perceptually linked to an urban metropolitan area, Helsinki, allowed further indexical shifts due to circulating tension between the ‘pure’ rural and the ‘sinful’ Helsinki as the imagined cultural space. Helsinki’s position as a stain on the national narrative in the cultural and linguistic sense, and as the centre of both the privileged elite as well as the performing stars, has evidently strengthened the indexical link between non-normative /s/ pronunciation and the capital area.

Had it not been for the fact that the most famous Finnish schlager stars were L1 Swedish speakers, it is possible that the idea of ‘Helsinki s’ would have died out long before the present times. But the rise of the new post-war popular culture happened to challenge the normative pronunciation of /s/, offering the fronted, hissing alternative as a stylistic choice. As observable in the present material, the educational agenda directly addressed this ‘problem’.

5.3 School Radio and other audio resources

The specific time context referred to in the anecdote presented by Ollaranta (above) is unknown, but examining the list of Finnish Eurovision Song Contest trial participants in the 1960s reveals that for example in 1967, one year before the publication of Ollaranta’s guidebook, two of the four artists – Marion Rung and Laila Kinnunen – were of Swedish-speaking background, both with a notably fronted /s/ articulation. The Eurovision Song Contest was in general notorious for having had many Swedish-speaking artists singing in Finnish during the 1960s, which reflected well the Finnish popular music scene of the era. Halonen et al. (Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020) documented the obvious clash of /s/ norms in the late 1950s and 1960s alongside the rise of popular culture (see also Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017). On the basis of the media documentation of the time, the enregisterment of the so-called schlager star /s/ had already happened in the 1960s, as Ollaranta’s guidebook explicitly reveals.

More recent evidence of this is the self-reflection of Virve ‘Vicky’ Rosti, one of the most well-known Finnish schlager singers, who started her career in the early 1970s. In a radio interview for the Finnish national broadcasting channel (Yle Radio 1) in 2008 she revealed that she had practised ‘an intentional s-defect’ similar to Laila Kinnunen and Marion Rung, in order to adopt the singing style of her idols and models. Another interesting piece of evidence can be found in the caricaturist Kari Suomalainen’s satirical cartoon published in Helsingin Sanomat (13 March 1963). In this publication, a young woman dressed up as a schlager star looks sad in front of a microphone, while a man with a cigar gives her feedback saying: ‘I’m sorry, but you cannot become a schlager star, as you lack the s speech defect.’ This strip reveals two things: first, that there was an indexical relationship between /s/ pronunciation and the schlager style, and that the pronunciation of /s/ indexing this style was judged to be a deviation from the norm, ‘a speech defect’ (see also Section 5.2). This perception was still present in Rosti’s interview as late as 2008, as she concluded (laughing) that she was ‘never able to get rid of that speech defect since’.

By the 1950s, there was already a deeply rooted normative understanding of the Finnish /s/, and that the fronted variant represented otherness (Swedish influence), which was to be avoided. The norms of proper Finnish were not only transmitted by the educational literature analysed in Section 5.2 but also with the help of such institutions as School Radio, founded in 1934 (Uusipaikka & Venäläinen Reference Uusipaikka and Venäläinen1987). School Radio was welcomed among practitioners in schools, as it enabled, by definition, ‘teachers and students from every corner of the country’ to engage with the programmes based on curriculum contents, including speech training. The value of this channel was in its auditive format, a particularly useful resource for language learning and speech training. It was possible for teachers to rely on audio example materials in their classrooms, such as rehearsals of pronunciation. Some of the School Radio materials were based on published guidebooks that were useful materials to use together with the radio programmes.

The speech defect discourse revolving around popular singers and their /s/ pronunciation seems to have been circulated in a dialogue between the media and educational materials. One indication of this is in the educational radio programme Jokamiehen puhekoulu (‘Layman’s speech school’) in 1964, when the topic was ‘Individual features in speech’ (Yle 26 October 2015). An interviewee in this programme was Inkeri Lampi, a specialist in speech education of students, specialising in early childhood education and care. In this programme, Lampi (IL) reflects on the important influence of teachers as models of speech for children and youngsters, but also brings up other sources as models for them. She mentions that at the age of upper secondary school, the youngsters follow models that are currently trendy, and that this often happens subconsciously. The following dialogue in the programme explicitly connects to Kari Suomalainen’s satirical cartoon published the previous year.

IL: As an example I could mention an article in a youth journal I read concerning a popular singer, who among other qualities had a piquant style of articulating [Finnish] in a foreign way.

Interviewer: This reminds me of a satirical cartoon published in a newspaper. An evaluation committee concluded that ‘unfortunately you cannot become a star since your s pronunciation is completely normal’. So I guess the piquant style was missing, then. I have noticed that young actresses articulate, or should I say, try to articulate the way their idol actresses do. I believe that profession modifies a lot the way we speak.

As is evident in the previous examples, the discourse on the Finnish norm in pronouncing /s/ in the 1960s is no longer as explicitly connected to the resistance to the Swedish influence as it was in the early decades of the twentieth century. The 1950s/1960s was the era when the originally nationalistic motivation to avoid fronted /s/ pronunciation as a characteristic of Swedish language blurred with the discourse of avoiding the sound as an indication of a ‘foreign’ influence, becoming an index of a schlager diva or attempts to copy such a style, as referred to in Kaikko’s and Ollaranta’s books (sources 4 and 5 in Table 1; see also Marjanen’s note in book 6). The same is echoed in the interview with Virve Rosti in 2008. Therefore, the ‘artificial prissiness’, originally characteristic of the Swedish L1 actresses performing in Finnish, was still at the heart of the social evaluation of the too fronted /s/ in the educational discourses during later decades of the century, as indicated above.

It seems that this indexical continuum motivated the speech therapy practice to continue addressing /s/ as a feature to be dealt with. This is well explained by the fact that the practitioners did not have any clear model or instruction to rely on in their professional solutions concerning the /s/, but they did their work guided by their own perceptions and general ideological understanding of what is or is not to be corrected (Rahkila Reference Rahkila1987:32, 34, Aittokallio Reference Aittokallio2002:11). By the time of the institutionalisation of speech therapy practice during the 1960s, /s/ correction had already become part of the systematic national agenda, a normalised practice that does not seem to have been challenged until much more recent times.

It must be noted that there is very little research available on the practice of speech therapy, in particular on the /s/. Aittokallio (Reference Aittokallio2002), however, provides interesting evidence on the language-ideological tensions among speech therapy practitioners of the 1990s. Based on qualitative questionnaire data distributed to speech therapy practitioners in Southwest Finland, the study revealed a disagreement among the professionals as to whether the fronted /s/ is to be corrected or not. Although Aittokallio’s data was relatively small, the results indicate that slightly fewer than half of the practitioners participating in the study considered the fronted variant as a deviation from the norm which should thus be corrected. According to some, the correction is only needed for some particular professions, such as teachers and journalists. Half of the respondents considered the fronted variant as an indication of the norm undergoing change from the bottom up, or as a stylistic resource. What these professionals in the 1990s mainly agreed on was that the fronted variant is more typical of females than of males (Aittokallio Reference Aittokallio2002:23–27, 72). In a way contributing to this understanding, Aittokallio also included an experimental study of /s/ pronunciation among 15 female students of different ages (primary and secondary school and older). The participants were recorded in several situations with varying interlocutors. The study revealed some intra-individual variation of /s/ pronunciation depending on the interlocutors, particularly among the upper secondary school students, who tended to produce more fronted variants if boys or adults were present.

It is important to note that Aittokallio’s speech data was not from Helsinki but from Turku, another bigger city with a considerably large Swedish-speaking population. It is possible that the variation of /s/ in Helsinki would turn out to be somewhat different from the variation in Turku, for example, but so far there is no evidence for this among contemporary Finnish speakers (see also Koivisto Reference Koivisto2022). In any case, both Aittokallio’s (Reference Aittokallio2002) and Koivisto’s (Reference Koivisto2022) studies suggest that there is some gender effect in /s/ pronunciation of Finnish, and Aittokallio’s study supports the hypothesis of fronted variants being a resource for stylistic choices. In addition, her study indicates that despite the strongly established discourse on ‘Helsinki s’ and the fronted variant as the stereotype of this ideological construction, the fronted articulation of /s/ is a feature that is certainly not limited to Helsinki. In terms of social meaning potentials, however, the essential issue here is that the /s/-to-be-corrected is ultimately perceptually connected, directly or indirectly, to Helsinki at least in the mind of the people (Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2013).

The fact that, among contemporary generations, a wide range of /s/ variants have been perceptually connected to Helsinki (Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015) suggests that the enregisterment of ‘Helsinki s’ as a construct in itself is based not only on linguistic divergence but also a sociocultural divergence, broadly speaking the rural–urban distinction, a deeply rooted conflict in the national narrative of Finland. In the present times, more so than in the past, the practice of and requirement for /s/ correction have never been overtly discussed in connection to place, but it is implied in different layers of sociocultural development, to which there is only a limited space to dedicate in this article (see Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020 for a more comprehensive analysis).

It is well known (and also observed by the authors personally) that at least in the 2010s, pupils in schools still had /s/ pronunciation education with the target of learning to avoid a too fronted /s/. The educational ideology on correcting the fronted /s/ articulation has been reflected upon from time to time in the media. Relatively recently in the news (Yle 30 August 2023), a decrease in the number of pupils in pronunciation education was inferred to be the result of a lack of speech therapists, not the result of a more tolerant attitude towards /s/ variation. The interviewed speech therapist, however, admitted being in favour of variation, stating that the ‘s and r deficiencies should be thrown into the garbage’. Currently, then, there seems to be a shift in ideology towards a more dialogical approach.

It would be interesting to explore in more detail the current educational ideology of /s/ and possible tensions among the practitioners. Contemporary generations still find the fronted /s/ variant(s) stigmatised and perceptually connected to Helsinki, as constantly evidenced in research and media discourse (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020). This was once again illustrated in March 2023 in a TV quiz show called Stadi vastaan Lande (‘Helsinki vs. the countryside’; Stadi is a slang name for Helsinki originating from Swedish stad = ‘city’). As one of the quiz questions, the team representing the countryside was asked Which letter [=sound] in the speech of people from Stadi is more prominent than others? It took less than one second for the team of three approximately 25-year-old men to press the button and respond: the s. The team was asked to imitate this distinctive /s/, but as a typical reaction to the imitation request (see also Vaattovaara Reference Vaattovaara2013, Vaattovaara, Kunnas & Saviniemi Reference Vaattovaara, Kunnas, Saviniemi, Brunni, Kunnas, Palviainen and Sivonen2018), the quiz team members preferred to settle for a metalinguistic description. An interesting detail is that while one of the team members noted that ‘it is somewhat prissy’, the other team member disagreed saying ‘I wouldn’t say it is prissy!’ Together they concluded that ‘it is scheiss [= shit], prissy scheiss’. This conclusion well illustrates the enregisterment of ‘Helsinki s’ against the norm of ‘the proper’, and the social meaning potentials still connected to the ‘Helsinki s’ stereotype: it is somewhat pretentious, certainly not normative, and not appreciated in the provinces.

6. Discussion

The findings presented above point to the wider normative discourses revolving around the pronunciation of /s/, and how these have been (re-)interpreted and circulated in society across time in the form of learning materials. The contemporary ideological understanding of the fronted /s/ variant(s) in Finnish society results from complex, long-term semiotic processes and layered sociocultural discourses throughout the twentieth century. The analysis in this article has addressed this historical continuum from the point of view of educational ideology.

We have explored the institutional and material approach to education on /s/ pronunciation in Finnish from the early 1900s to the 1970s. The analysis has provided transparency into how the Finnish formal education system has educated past and at least some of the contemporary generations in /s/ pronunciation in Finnish. The status of the phoneme /s/ as the only sibilant in the phonetic inventory of Finnish would, in principle, allow relatively free variation, but as the analysed educational material reveals, the instructions concerning /s/ pronunciation have been puristic throughout the investigated decades – long after the original concern about a Swedish threat to Finnish.

According to Paunonen (Reference Paunonen1996), the judgements of ‘correct’ and ‘incorrect’ and ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Finnish in general have been dominant in the discourses of Finnish language throughout the twentieth century, originating from the Fennoman movement and purism of the nineteenth century. This is also well illustrated in the case of /s/, as evidenced here. In particular, Saarimaa’s extensive production achieved a canonical status among teachers and other professionals on the norms of the Finnish language, transmitting the puristic language ideology, to some extent still observable in discourses on proper Finnish (Paunonen Reference Paunonen1996, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020:150–157).

The analysis of the generally well-known and widespread guidebooks as well as auditive educational resources (radio programmes intended for learning purposes) indicate that the tone of judgement on non-normative /s/ has remained relatively unchanged from one decade to the next, despite the major sociocultural and political changes in Finland during this time. The analysis of guidebooks published during the first seven decades of the 1900s, however, reveals the dynamic relationship of normative discourse and cultural change. The rise of popular culture in the 1950s materialises in the way non-normative /s/ is judged in the books intended for education, again circulating the ideological connections. The /s/ was by no means the only feature under the magnifying glass of the norm developers and educators, but the fact that it has been perhaps the most salient one, or at least publicly most widely discussed one, is explained by its strong indexical link to Helsinki and the imagined ‘Helsinkinesses’ (see Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020 for a more comprehensive analysis).

The concept of ‘Helsinki s’ per se has not been used in the educational materials, but the indexical relationship between Helsinki and non-normative pronunciation is transparent in the material. As already documented in our earlier studies, the concept of ‘Helsinki s’ dates to the nineteenth century when the fronted /s/ was pointed out as a threat to proper Finnish. The too fronted /s/ of, in particular, the L1 Swedish-speaking female actors among the first Finnish Theatre performers has been a target of verbal hygiene since at least 1885. In fact, in the mouths of the L2 Finnish-speaking actresses of the time, ‘Helsinki s’ was a linguistic fact. The judgement of the fronted variant of /s/ as artificial and prissy originates from this era, constructing the indexical relationship with Helsinki (as a sinful place). The fronted /s/ came to people’s attention in the provinces via theatre reviews, but more systematically through education that was transmitted by the institutionalisation of the linguistic and phonetic education system.

The present analysis shows how the line of judgement on the fronted /s/ has stood the test of time from the early processes of nation building of Finland until its establishment as a modern Nordic welfare state with a vital official national language. Before the 1970s, the endpoint of our material investigation here, the notion of Swedish language as a threat to Finnish language had faded a long time ago, but the core of the ‘Helsinki s’ ideology has remained largely unchanged, presumably due to the fact that the fronted /s/ started to gain new recognition with the rise of popular culture since the 1950s, indexing the modern, the urban, or the cool (see Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020). Now in the mouths of (female) popular singers the fronted /s/ continued to index a new type of ‘artificial prissiness’ which, in the new cultural context, turned out to be more of a stylistic asset for artists rather than a flaw. This development is visible in the guidebook material investigated.

Since the turn of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries at the latest, the fronted variant of /s/ in Finnish has met more global styles indexing in one way or another prominent, overdone, unsophisticated, or unrefined femininity, including male (queen) gayness (Halonen & Vaattovaara Reference Halonen and Vaattovaara2017, Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020). While the indexical connection between gayness and fronted /s/ has been indicated as a relatively global phenomenon (e.g. Campbell-Kibler Reference Campbell-Kibler2011, Rácz & Shepácz Reference Rácz and Shepácz2013, Levon Reference Levon2014), in the Finnish context the history of the indexical properties of /s/ variation is more complex. In Finland, the present-day global influences with new indexicalities have, however, hit fertile ground in the history of popular culture preceded by the history of nation building of Finland and the construction of norms of proper Finnish.

Any linguistic feature associated with Helsinki typically still faces prejudice, and connotations of conceitedness and arrogance (e.g. Mielikäinen & Palander Reference Mielikäinen and Palander2002, Vaattovaara & Halonen Reference Vaattovaara and Halonen2015). Due to its status as the capital metropolitan area, Helsinki also has covert prestige in the speech community, which partly explains why the non-normative fronted /s/ pronunciation has gained status as an index of certain subcultures and styles (Halonen et al. Reference Halonen, Nyström, Paunonen and Vaattovaara2020). Performing a fronted /s/, or reporting having one, has also become a means to claim that one is from Helsinki. It thus seems that there are at least two distinct norms at play (see Levon Reference Levon2014, Pharao, Maegaard, Møller & Kristiansen Reference Pharao, Maegaard, Spindler Møller and Kristiansen2014). Officially, and largely explained by the indexical relationship between (the notorious) Helsinki and speaking differently from the norm, the so-called ‘free variation’ of /s/ has not led to tolerance of variation but quite the opposite: normative strictness. Similarly to some studies on linguistic variation concerning foreign accents, for example (see Garrett Reference Garrett2010, Kristiansen & Coupland Reference Kristiansen and Coupland2011, Grondelaers & Kristiansen Reference Grondelaers, Kristiansen, Kristiansen and Grondelaers2013), in the case of Finnish /s/ a ‘natural’ linguistic variant has been deemed as non-normative and non-standard when too fronted.

The switch in the ideological climate documented in Aittokallio’s study using data from the 1990s, and pointed out in the recent media data in interviews with speech therapy professionals, does not seem to connect in people’s perceptual landscape at quite the same pace as the (now dying) institutionalised practice of /s/ correction in schools. The educational discourse and the ‘Helsinki s’ discourse seem to exist as completely distinct discourses. The core of these seemingly distinct discourses lies in purism, the possible competing discourses being erased in the indexicalisation process (cf. Irvine & Gal Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). As evidenced in the present analysis, both discourses stem from the same history. The identification of L2 speakers of Finnish ‘fronting’ their /s/ was judged by the early Fennomans as first having been Swedish influence, which then developed into, in Silverstein’s (Reference Silverstein2003) terms, a second- and third-order index of various ‘deviations’– prissy, pretentious, or artificial. Much like Helsinki, as a place, has been positioned as ‘sinful’– deviant, foreign, pretentious, and artificial – in the national imagination and narrative, so too has the fronted /s/ been associated with speakers from Helsinki or particular styles associated with the capital region.

It can be concluded that while the Finnish educational system has not been completely successful in its agenda to educate Finns in /s/ pronunciation in accordance with the voiceless alveolar norm, it has consistently contributed to the perceptual continuum of the social meaning potentials of /s/ in Finnish society. The stigmatised way of speaking differently from the norm first came to people’s attention in the provinces via theatre reviews and such like, but more systematically also through formal education, in the form of learning materials. The legacy of August Ahlqvist and his contemporary colleagues has taken root, and although challenged by the cultural changes with the new stylistic repertoires ever since the 1950s, the normative climate was not yet subject to change for many decades. The case of /s/ is an example of how deeply rooted language ideologies, such as purism, can be slow to change. The language-ideological shift starting in Finland around the 1980s/1990s, only briefly touched on here, certainly deserves more attention as a separate study.

7. Conclusions

The present article set out to focus on the educational trajectory of the norm of /s/ pronunciation: How have Finnish speakers been brought up to avoid fronted pronunciation(s)? The analyses presented in this article add to the transparency of contemporary social and non-normative salience of fronted /s/ in Finnish society, already documented in earlier studies. Here, analysis of the Finnish educational system and key educational materials from the early 1900s to the 1970s cast a brighter light on the enregisterment of the construct of ‘Helsinki s’ and its connection to the purism triggered by the nationalistic agenda of the nineteenth century. Although not connected in non-linguists’ perceptions, and not necessarily even in the practitioners’ minds, the present study showcases the connection of the two parallel, normatively oriented discourses of (resisting) Swedish influence and (resisting) ‘Helsinki s’. The perception of ‘Helsinki s’ still seems to keep transmitting to new generations, and it is possible that it might still develop to become a proxy for various types of ‘non-normative’ /s/ pronunciation on one hand, and social categorisations on the other. This possibility, and the role that the current new educational ideologies play in this, remain to be studied in the future.

Acknowledgements

We warmheartedly thank our colleagues Heikki Paunonen and Samu Nyström for co-researching ‘Helsinki /s/’ with us for many years. To this collaboration we owe the journey to the historical documentations and many of the findings concerning enregisterment of ‘Helsinki /s/’, as well as to our initial motivation to delve into /s/ ideology from the educational point of view. We would also like to thank Marja-Sorjonen, Liisa Raevaara, Hanna Lappalainen, Heini Lehtonen, and Dennis Preston for fruitful discussions during 2009–2012 while working on our earliest studies dealing with the /s/ ideology. We are grateful for the insightful and inspiring comments by anonymous reviewers, which helped us to develop the manuscript, and we thank the Editors for their valuable further comments.