Introduction

When the Greek state was established after the 1821 Revolution against the Ottomans, its ravaged land was inhabited by a very small percentage of the Greek diaspora. Greek nationals living and prospering in Asia Minor and Europe, having contributed significantly to the preparation of the Revolution, played an equally decisive role in the progress of the country. Before the establishment of the new state,Footnote 1 both Greeks and Europeans, at least since the eighteenth century (Burney, Hawkins, Padre Martini, Fétis etc. and a large number of travellers), speak of ‘Greece’, referring to areas that would later be annexed to the country – Epirus, Western Thrace and Macedonia, the Ionian Islands and many islands in the eastern Ægean sea – as well as areas beyond today's borders inhabited then by compact, well-organized Greek communities in several cities of Asia Minor.

The music education of people living under such diverse cultural influences was necessarily quite dissimilar and varied. All variations, however, resulted from the confrontation and interaction of two musical cultures, the music of the Greek Orthodox Church – applying a special notation, appropriate to its monophonic, unaccompanied chant – and Western music. The dissimilarities were conditioned by the degree to which the assimilation of either culture prevailed in local traditions. The antithesis of those musical cultures was best represented, at least up to the 1850s, among the Greeks living in Constantinople and Corfu, two cities that have greatly influenced music education in Athens, the capital of the Greek state since 1834. We believe, therefore, that an examination of music education in nineteenth-century Greece can be limited to those three cities and still be representative, and in the following text we will move from Constantinople to Corfu and finally to Athens.

Constantinople, the seat of the Greek Orthodox Church was, during the Ottoman captivity, the religious and political centre of all Orthodox Christians. Faith carried a strong social identity well before the diffusion of nationalistic ideology to that area. Yet, Constantinople was also a cosmopolitan city in the nineteenth century; it was inhabited by many Westerners, part of its population was in contact with the West and many Greeks had wider cultural horizons.

Although Corfu had never been under the rule of the Ottomans or neighbouring Italy, it had been subject to the Venetians, French ‘liberators’, Russian ‘mediators’ and English ‘protectors’, and was inhabited by many subjects of those conquering nations as well as many Italians.Footnote 2 Aristocratic Greek citizens had access to state positions and to Italian schools and universities, both as students and professors. Musical life in the city was closely related to that of most Italian cities, which, during the first half of the nineteenth century, did not for the most part participate in the musical culture that flourished beyond the Alps.Footnote 3

Athens was chosen as the capital of the new state of Greece in 1834 because of its ancient history and monuments. It was a rural community around the Acropolis, attracting inhabitants from all the destitute villages on the mountains and islands of the new state.Footnote 4 Likewise, well-educated Greeks came from abroad, along with many foreigners serving the Bavarian royal court, diplomats and Christian missionaries.

Hence, not until the very last pages of the following narrative – corresponding to the last decades of the century – will most of the familiar names and terms that appear in nineteenth-century Western music histories be brought into the discussion. To present music education in nineteenth-century Greece is to describe characteristics of previous centuries of Western music history. In some respects, it is to expose the synchronous occurrence of the characteristics of successive periods. Although this might also be the case with other people temporarily isolated from the West, what makes the case of Greece singular is the fact that Europeans saw Greeks as the progenitors of ancient Greek civilization, an achievement that has engendered their admiration and awareness of the debt owed to them by Western culture.

This admiration was extended to Greek traditional music (which, having been developed in isolation, preserved qualities that were considered original), that was seen to be related to ancient Greek music. The idea of protecting traditional music from further development was, consequently, widespread in a community that had not yet confronted culture as an object of study and investigation. Equating progress with bringing music evolution to a standstill was confusing and brought continuous obstacles to all efforts of Greek musicians to synchronize their music with that of the West; it also established much too early in Greek folk music the distorted relationship between the educated and the folk (the former instructing the latter) and barred many pure musical talents from developing their art or from being educated.

Constantinople

Constantinople was to Greeks under the Ottoman dominion a cultural metropolis, not just an ecclesiastical centre. The antithesis between ecclesiastical and secular music had not acquired a firm distinction there yet. As is the case in contemporary eastern countries with a strong presence of the church in everyday life and a close relationship between the church and the political power, in a similar way, to Greek residents of Constantinople, church chant predominated in everyday musical life. The secular and popular character of the Orthodox Church was recognised, and its chant was sung at banquets and at work as well as in church. Popular hymn tunes were used at school to teach geography, rules of grammar and arithmetic or to tease friends and foes.Footnote 5

This secular physiognomy was sustained by the policy of the Ottoman dominators, which assigned all communication with the people to church leaders. As was the case with Byzantium, the subjects of the Ottoman Empire were diverse in race and origin as well as in languages spoken, while communities had been frequently displaced. Uneducated people confirmed their identity through religion. ‘They weren't Turks, they were Christians.’Footnote 6 For many of the above reasons, Greek language was, in both empires, spoken and written widely by educated Christians.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, knowledge and ideas spread by the promoters of the so-called Greek EnlightenmentFootnote 7 were conceived as a threat to the Greek church's political authority and social status, not only for their anti-clerical content, but also because of their emphasis on ancient Greece as the predecessor of the nation. This idea was considered dangerous by some for both the Ottoman Empire and the Great Church, despite the fact that it had been vastly propagated in past centuries in order to solidify the unity of the Byzantine Empire.Footnote 8 Indeed, the relationship of Byzantine to ancient Greek civilizationFootnote 9 (and of modern Greek culture to either or both), is a problem present in all depictions of modern Greece.

International politics were also involved in this issue. Most important of all, the Russian Church was seen as a potential successor to the Great Church's dominant role in Eastern Europe. During the first two decades of the nineteenth century, which were so crucial for the future of Greece, the Ottoman Empire and the Great Church, Constantinople's patriarchs were filtering information on the activities of the clergy. It was during this short period, in which the relations of the Great Church to Enlightenment ideology, its supporters, its factions and their representatives were at their height, that in 1815 the first patriarchal music school was founded.Footnote 10

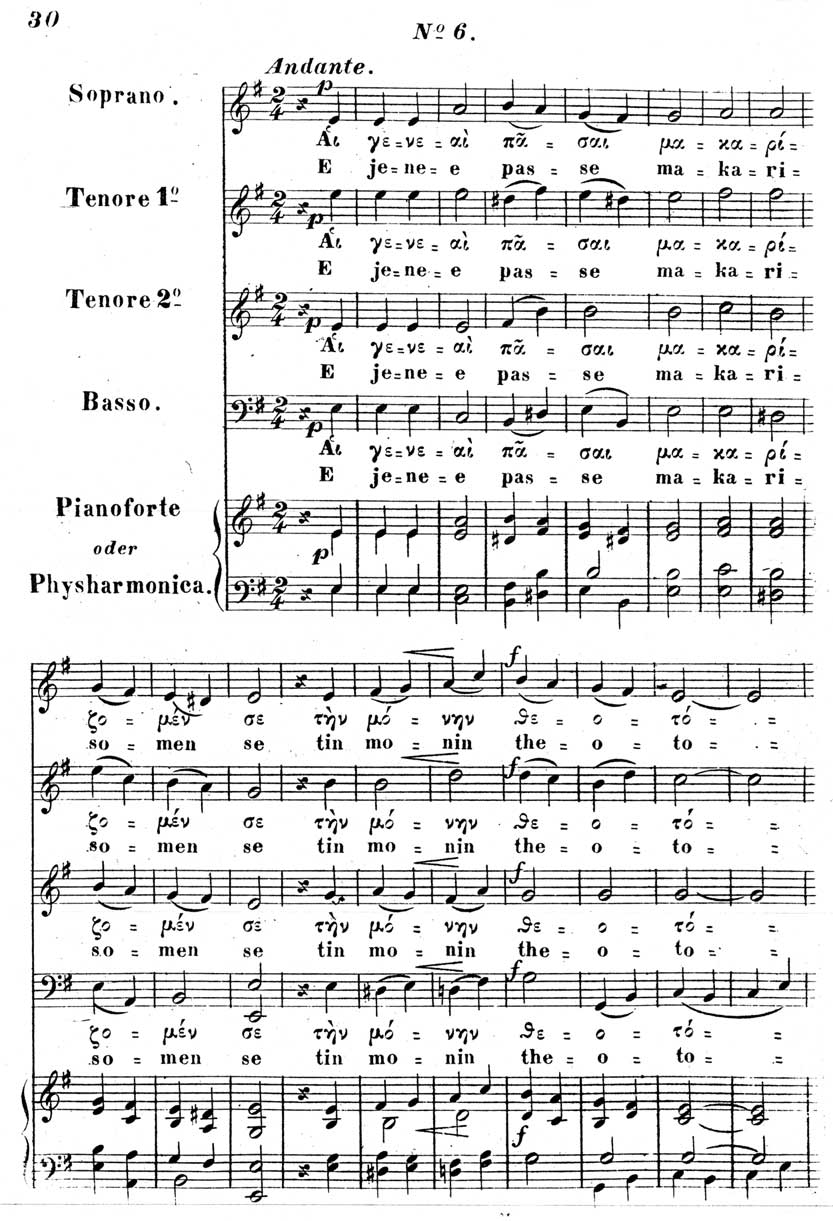

This school was set up expressly for the instruction and dissemination of the reform of Byzantine musicFootnote 11 notation, conceived by Chrysanthos of Madytos, an enthusiast of these enlightened ideas. His significant work had remained unknown for some time (until the emergence of a group of progressive clerics in the patriarchate), while a very important part of it would be published only in 1832 in Trieste. Chrysanthos’ reform enabled, for the first time in history, the printing of Byzantine music – it had, up to 1820, circulated in manuscript – and was taught in a traditional, practical and time-consuming manner. Students of the new school graduated in two years. The programme of studies is not known. An exam questionnaire – with the correct answers – published in the periodical Hermes ho Logios Footnote 12 is conventional and scholastic, but several texts by the school's graduates testify to an inspiring and modern schooling. The publication of the questionnaire, and other information about the school, in Hermes ho Logios, highlights Chrysanthos' image as a supporter of the Enlightenment. Because Hermes ho Logios was a Greek periodical published by the Greek community of Vienna (but funded by Greeks in Bucharest), this brought together Greek intellectuals dispersed over Europe and Asia Minor who were aiming for the cultural and national revolution of the Greeks.Footnote 13

Fig. 1 The title page of the Greek periodical Hermes ho Logios, published in Vienna (1811–21)

Many graduates of the first patriarchal music school were sent to Greek communities – mainly in the Balkans and Western European cities – to transmit their knowledge. Indeed, the dissemination of the new method of notation was effectively fulfilled in an impressively well-organized manner and short time. Two of the graduates, entrusted with the supervision of the manufacture of printing types for the neumes and the printing of the first books, were sent to Bucharest and Paris. In Bucharest in 1820, two important music books were published for the daily church service (which had been transcribed by Chrysanthos’ two main collaborators, Gregorios Protopsaltes and Chrourmouzios Chartophylax). In Paris, a manual for the instruction of the notation was published in 1821, together with one of the music books that appeared earlier in Bucharest.

Thamyris, who supervised the work done in Paris, was assisted by the Greek librarian of the Institut de France, Constantinos Nicolopoulos, a student and collaborator of F.-J. Fétis. Because of this connection, Fétis gives ample information on the people involved in the reform of the notation and many of the related events in his two major works.Footnote 14 Fétis supports the assumption that Chrysanthos was enthusing his students with all the ideas circulating by exponents of the Enlightenment.Footnote 15

Both books published in Paris were introduced to the readers with a foreword written by Thamyris.Footnote 16 The first printing of the handbook containing Thamyris’ text was quickly recalled and the book circulated again without the foreword or mention of its editor. Published in an edition of 1978, this foreword fervently praises the enlightened ideas of which the New Method is representative, since the time required for the study of music was significantly reduced, ‘leaving free time for studies more advantageous to social life’. It makes frequent reference to Adamantios Coraes, one of the leading figures of the Greek Enlightenment, J.J. Rousseau and ancient Greek philosophers. Thamyris uses harsh, ironic and disrespectful expressions against the old music teachers, whom he calls ‘completely ignorant’. He concludes by advising his fellow students: ‘Do not confine yourself to our music; study European as well, if you wish ours to reach its highest level.’Footnote 17

Chrysanthos’ involvement in the modernization of education is better demonstrated in his book Great Theory of Music (1832) edited by Panagiotes Pelopides, another of his students. It appeared in Trieste, which had been inhabited since the eighteenth century by a large, educated and wealthy Greek community highly regarded by the local population. The first of its two parts deals systematically and comparatively with the theory of ancient Greek,Footnote 18 Byzantine, Ottoman and European music, while the second provides the first general history of music in the Greek language in modern times. Therein Byzantine and post-Byzantine musicians take their place in history after ancient Greek musicians and those mentioned in the Bible. Western musicians are also mentioned.

Fig. 2 The title page of Chrysanthos of Madytos' important book, Great Theory of Music, published in Trieste (M. Weiss, 1832)

To sum up, Chrysanthos’ overall contribution to music education fulfilled many aims of the Enlightenment: new educational methods were employed; schools were founded; simple teaching treatises were published; young people were sent abroad to broaden their views; the number of music teachers augmented, the heredity of ancient Greek culture was pronounced; and the study of Western civilization encouraged.

The patriarchal school where Chrysanthos taught was already closed before the Greek Revolution against the Ottomans broke out in Peloponnesus in 1821. Patriarch Cyrillos VI, who had supported Chrysanthos, was succeeded in 1818 by Gregorios V, whose anti-Western sentiments and politics did not conform with Chrysanthos’ teaching and work. Chrysanthos’ effort to introduce Western music science in a school supported by the church was an exception to the policy followed subsequently by schools of the Great Church in Constantinople and by the autocephalous Greek church,Footnote 19 which was later based in Athens.

The Westernization of the East

The Crimean War (1853–56) was crucial in tightening economic relations between the Ottoman Empire and the West, a fact that brought many changes to the society of Constantinople. ‘Τhe Ottoman capital began to acquire a European appearance’, while ‘certain families of the Greek Ottoman business elite shifted from trade to banking.’Footnote 20 In the 1860s ethnic communities of Constantinople ‘began to found clubs (theatre, music, sport) and cultural, educational and charitable associations’.Footnote 21 The elite multiethnic community of Constantinople acquired a more cosmopolitan character, incorporating many Western Europeans working in the city. French replaced Greek as the common language.Footnote 22

Fig. 3 The title page – in French – of a Marche Triomphale composed by the Greek resident of Constantinople, Alexandre Eustathiadis, and dedicated to the Sultan. Psachos archive, Music Department of the University of Athens

It was then that a distinction between sacred and secular culture affected musical life and music education in this region. It was then also that the Ottoman Turks begun to realize the importance attributed in the West to ancient Greek culture,Footnote 23 a development that encouraged local Greeks to get involved in the study of ancient Greek music.

This resulted in the rapid growth of Greek secular music societies and the gradual confinement of church music schools to priests and other people connected to the church. Three patriarchal music schools were founded after Chrysanthos’ (in 1866, in 1868–72 and in 1882). In all, the intention was to deal with Byzantine music in a scholarly way. The second school initiated the periodical publishing of important old music manuscripts under the general title Musike Bibliotheke, of which only two issues circulated.Footnote 24 The third school was connected to a committee that undertook to modernize the instruction of Byzantine music, motivated by the realization of the rapid dissemination of Western music in the city. The committee – that shared some of the school's staff – assembled in 1881 to decide on the exact values of the intervals applied in chanting, defining their pitches in terms of vibrations, as well as the metronomic values of the tempi appropriate to the various chants. The committee also decided on the repertory that should be used in churches, excluding some recently composed chants that were heard at that time. For the sake of uniformity in chanting, a keyboard wind instrument (a harmonium) was constructed in 1882, producing the intervals as measured by the committee, because the influence of the equally tempered scale was considered detrimental, while the application of keyboard instruments in ear training, very effective.Footnote 25 The harmonium was used by the school's teachers, but its technical deficiencies were more serious than its pedagogical merits, and it was abandoned before long.Footnote 26

Music schools independent of the Great Church are not known to have existed prior to 1880. The first music society was founded in April 1863 but it seems that its aims were of a musicological nature. Very little is known about it. It was dissolved shortly before 1870 because of disputes among its members.Footnote 27

Georgios Papadopoulos (1862–1938), a very active and well-educated musician, was fast to conceive a way out of the impasse church music education had experienced. He became involved in secular music societies and convinced its members to include church music in their repertory and instruction, arguing that Byzantine music is not church music, but the music of the Greeks, and that all music may be written using its notation. In 1880 Papadopoulos was among the founding members of the Greek Music Society of Constantinople. It had a school which was dissolved after three years of successful functioning.Footnote 28 Moreover, the music society Orpheus was established in 1886. During its first year, only Western music was cultivated. But in 1887 Papadopoulos became involved (assuming the society's presidency in 1889) and opened a school for church music which operated up to 1890, until it was closed ‘obeying government orders’.Footnote 29

In a long speech delivered on 1 October 1889,Footnote 30 Papadopoulos gave much information on the society's work and prospects. Most of the information below derives from it: Orpheus had a large mixed choir conducted by the Italian Raffaele Ricci.Footnote 31 The choir had in its repertory over 50 pieces by Western composers. When Papadopoulos assumed the society's presidency, it was rehearsing in order to participate in a performance of Bellini's Norma, but the performance was prohibited at the last moment by the government. Among the reasons why Orpheus was focused on Byzantine music was to preserve its identity in response to the rapid dissemination of European music in Constantinople. ‘Piano sounds attack our ears while walking in the streets of most neighbours’, said Papadopoulos, adding that, whereas in Greek schools children were taught European songs only, they should be taught ‘our’ music as well. He proposed that all Greeks be taught neumatic notation and that European songs be transcribed in that notation, which would thus become indispensable not only to chanters but to all music lovers.Footnote 32

Fig. 4 Writing polyphonic music with reformed Byzantine notation. A transcription from a Gloria by Alexandre-Étienne Choron. Chrysanthos of Madytos, Great Theory of Music (Trieste: M. Weiss, 1832), 222

He also proposed that good Greek chanters be sent to the West to study Western music and spoke about the need to produce Greek editions of all the ancient Greek treatises on music, being aware of what has been done in the West in that respect. He emphasized the need for ‘scientific treatises of our music’, and to assign to good musicians the task of collecting folk music. He commented on the aversion shown by girls of well-to-do families of Constantinople to folk songs – they only sang European songs.

Papadopoulos’ concern for Greek folk music is an indication of the great impact on Greek musicians produced by the circulation in 1876 of L.A. Bourgault-Ducoudray's Trente mélodies populaires de Grèce et d'Orient (Paris-Bruxelles, Henry Lemoine et Cie). Although this is not the first collection of Greek folk music, its popularity among Greeks was extensive, due especially to the discussion of the similarities of the songs’ modes to ancient Greek tones, and also to the fact that Bourgault-Ducoudray was connected to many Greeks in Constantinople, Smyrna and Athens.

Fig. 5 L.A. Bourgault-Ducoudray, Trente mélodies populaires de Grèce et d'Orient, fourth edition (Paris-Bruxelles: Henry Lemoine et Cie, [no date given for this edition; first edition by the same publisher, 1876])

The Greek Music Association was founded in 1880, and was active for four years. Its committee was interested in secular and church music, but also in the music of Eastern cultures. Members of this association also participated in the committee that constructed the harmonium mentioned above. It also established a competition for the publication of a music book containing secular music (in neumatic notation). A music school annexed to it opened in May 1882. Over 100 students were enrolled in its three classes, but it operated for only one year. Georgios Papadopoulos taught the history of Greek church music. Notable among the honorary members of this association was Richard Wagner, at whose death, the association sent an official letter to his family, and a laurel wreath, presented at his funeral by two other honorary members who acted as the association's representatives.Footnote 33 This could be seen as an example of Papadopoulos’ aspirational idea that Greek church music could develop in parallel to Western music as its equal.

Corfu

In 1824 Frederick North, Fifth Earl of Guilford (1766–1827), called ‘Guilford’ in Greece,Footnote 34 founded, in Corfu, the Ionian Academy, the first Greek University since the Fall of Constantinople. This British nobleman was a fervent philhellene, connected through friendship and common ideology to Coraes, Constantinos Nicolopoulos and other proponents of the Greek Enlightenment and the Greek Revolution. Indeed, Guilford, as well as Coraes and Nicolopoulos, published several times in Hermes ho Logios, the progressive periodical mentioned above.Footnote 35

Fig. 6 A page from Ioannis Aristides’ manuscript collection of chants for the Holy Week. The melody is accompanied by figured bass. Corfu Philharmonic Society

Guilford had first travelled to the west coast of Greece and the Ionian Islands from 1791 to 1792. In a second trip from 1810 to 1813, he reached deeper into the East and Asia Minor. In 1811 he was in Constantinople, and it was there that he first conceived the idea of a Greek university, talking about it with some of the young intellectuals who contributed to the secularization of education in Greece.Footnote 36 Desiring to create a genuinely Greek institution, Guilford went to all the places known to him for having successful Greek schools or educated Greek communities. He chose promising youngsters to teach at the academy, whom he sent to study in Europe at his own expense.

Guilford was quick to realize the amount of effort and time required to bring the Greek people to a cultural level worthy of their ancestry. He also realized the extent to which their recent history was tightly interwoven with their religious dogma, and the danger of ignoring this in a time that Christian communities of the East were flooded with missionaries of Western churches.Footnote 37 It was his belief that church music was elemental to the music culture of any people. In order to assure the edification of the Greeks, he visited Russia in 1818 to gain information on the education of the Russian clergy for use as a model for education of Greek clergy.Footnote 38 His initial intention was to found a music department where ‘ancient and modern, sacred and secular music’ would be taught.Footnote 39 But he faced significant problems, most of all the unwillingness of the wealthy bourgeois to share their privileges with members of the lower classes. In a letter to an Englishman he criticized local aristocrats’ lack of concern for the people: ‘There are still many of the principal persons, who suppose that the small stock of knowledge under their perriwigs must be guarded by a strict monopoly and that it is not of near so much importance that the clergy should be able to read.’Footnote 40

Despite all obstructions, music was taught in the academy but was confined to church music. It was taught by Ioannes Aristides (1786–1828), a deacon from Ioannina serving the significant Greek community of Livorno around 1814,Footnote 41 who was sent by Guilford to study music and ancient Greek literature in Naples. According to a contemporary author, the specialization of the academy's music department greatly disappointed young men eager to study bel canto,Footnote 42 because the core of musical life in their city was Italian opera and not Greek church music. Aristides’ lessons were attended by only a few students, who decreased in number every year. Aristides had no successor in the academy at his death, and music was no longer taught there. The academy had reduced its places and teaching hours at Guilford's death a year earlier.Footnote 43

Thereafter, music education was undertaken by the Philharmonic Society, founded in 1840. It assumed a leading role in Corfu up to the end of the nineteenth century, and beyond.Footnote 44 Nicolò Chalichiopoulo Manzaro (1795–1872), an aristocrat, was life president of the Society. During his times and up to this day he is recognized as the musician who most effectively moulded Corfu's music education. Corfu's Philharmonic Society was far more representative of the city's cultural tradition and the people's taste than was the music school of the Ionian Academy. Church music represented a low percentage of the repertory taught in the Society or performed by its various ensembles. The Society's teachers of church music made use of Aristides’ material, each adding his own modifications.

The entire corpus of this material, which is polyphonic, written in manuscript and in staff notation,Footnote 45 shows the gradual reduction of improvization in the instruction and performance of this music (in parallel with a tendency to hellenize terminology).

Fig. 7 A melismatic chant in the third echos (mode) with a figured bass; from Ioannis Aristides’ manuscript collection. Corfu Philharmonic Society

Fig. 8 Benedict Randhartinger's harmonization of the Greek Orthodox liturgy. A page from the second edition published in Vienna in 1848

Fig. 9 The Olympian Exhibition, a march for piano by Georgios Lampires, published in Athens for the Olympiad of 1888. Motsenigos’ Archive of Neohellenic Music, National Library of Greece

Fig. 10 The title page of a Turkish march dedicated to the Sultan who won the 1897 War. (Pharsala is the town in Thessaly where the second battle of this war was lost for the Greeks). Psachos archive, Music Department of the University of Athens

It should here be noted that improvization of a second and third part is a popular tradition in this area, as it is in many places at the eastern coast of the Adriatic and in Italy's south; it had been supported in education by the semi-practical method of teaching harmony jointly with counterpoint, known as partimenti. Giuseppe Zarlino, Charles Burney, Padre Martini (exposing the experience of the Abate Cirillo Martini),Footnote 46 and other Western musicians observed this practice exercised by Greeks living both in Venice and the Ionian Islands and described it as a particularity, since Greek church music was, as a rule, monophonic. In the material kept in the Philharmonic Society's library there are elaborate adaptations signed by Nicolò Chalichiopoulo Manzaro. They are usually in four male voices, but some are for six voices including two soprano parts, inscribed ‘Coro di fanciulli’; almost all have a piano or organ accompaniment.

Indeed, to Manzaro as to many Greeks with no contact with the East, all music should progress towards the forms it had acquired in the West. Harmony, polyphony and instrumental accompaniment were conceived as improvements. Manzaro functioned as a composer, not a church musician. He had also composed two masses for the Catholic rite, one of which had been performed in the church of Saint Ferdinand in Naples. At least up to the 1830s it seems that Manzaro was not conscious of the confusing issue of the ‘correct’ manner of chanting, which called for wedding a local tradition to a ‘national’ style – which was far more Eastern (and as such, less progressive) than the traditional one.

Manzaro had never travelled to the East. All his trips were to Italy (the years 1819, 1822–23, 1824, 1825–26 and 1843).Footnote 47 In fact, his absence from Corfu may be one of the reasons why he presumably never met Guilford since, as far as we are aware, there is no mention of each other in all the documents of the two men. Manzaro's early trips were mainly to Naples, where he was befriended by Zingarelli and was taught by him in the Conservatorio of San Sebastiano.Footnote 48

As was the case in Naples and so many Italian cities of the South, opera was regarded in Corfu as a popular and ephemeral artistic product. It was permitted to be divided up, paraphrased and transcribed by anybody; its extracts were disseminated in a number of versions. As a result of this melody retained a dominant role and music flowed from the theatre to all neighbourhoods of the city and to all citizens. It also ensured the success of works, popularizing them both in outdoor performances by wind ensembles and introducing them into bourgeois homes by various transcriptions for the piano and for small ensembles. Thus did such diffusion build cultural communication between classes. The original work was continuously transformed into familiar structures, making the individual work become collective.

Il Nobile Teatro di San Giacomo, Corfu's opera house, produced exclusively Italian operas during the first half of the nineteenth century, as frequently and as regularly as most opera houses in Italy. The Philharmonic Society played the role of disseminating extracts, mainly through its wind band. But Manzaro, assuming the presidency of the society, lent it other functions and qualities distinctive of most Italian music education institutions, namely, the philanthropic objectives of the Italian conservatorios, (especially the Neapolitan) and the scholarly character of some academies. Corfu's Philharmonic Society served also the patriotic and military goals of the French Conservatoire de Musique in its early years. The philanthropic character of the society is well demonstrated in its initial announcement for the foundation of its wind band, published on 16 November 1840. It asked that gifted young men over 15 years of age be taught an instrument and become members of a band. The announcement ended with the assertion that ‘It is no obstacle if one does not know how to read or write, since the society will take care of this.’Footnote 49

Nicolò Manzaro's personality contributed substantially to the pedagogical role of the society. His devotion to the musical education of the people and the sacrifices he went through to that end, were disputed by no one. A document, dated 28 June 1855, justifying the Ionian Government's decision to grant Manzaro a life pension, does not exaggerate his devotion:

Because the knight Nicolò Manzaro, having consecrated the greatest part of his life to the study of musical art, is greatly excelling among nationals and foreigners for his intelligence and his most deep knowledge; because not only does he honour thus his motherland, but benefits it also teaching incessantly, years now for free, young music lovers, sacrificing his personal interests to the cultivation and dissemination of Art; because it is correct … to reward whom ever so bravely and efficiently labours for the honour and enlightenment of his homeland; we decide.Footnote 50

The scholarly character of the society was supported by few among its founders, who had in mind an institution on the model of the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna. In many early documents the society is called Music Academy of Corfu.

Long meetings of intellectuals and students are reported on many occasions. Descriptions of such meetings suggest that music was performed, poetry was improvized or recited and long discussions were held on subjects connected to music analysis, æsthetics, or politics. Among the participants in those meetings was Manzaro's close friend and collaborator, the poet Dionysios Solomos, on whose work the musician based his most popular songs in Greece, including the Hymn to Liberty, a long poem relating heroic events of the Greek Revolution, commenting on Western powers’ hypocritical behaviour and conversing with Lord Byron (in his Don Juan). The Greek national anthem consists of the first verses of this collaboration.

A curriculum of the Philharmonic Society's school of music

We have detailed information on the curriculum of the Philharmonic Society's school of music as was proposed by Manzaro. The school was divided into departments of performance and composition. The former offered instruction in wind instruments, the instruments of the violin family and the piano. The latter had classes of harmony and counterpoint (combined through the method of partimenti), and the forms of music. Internal or external male students over 15 years of age enrolled for professional training, while boys and girls were accepted as amateurs and were offered courses in the piano and partimenti. As a rule, lessons were delivered for three hours in the morning and one in the afternoon. Manzaro taught composition from 1842 to his death. The much-admired treatises he wrote for his lessons remained unpublished.Footnote 51 Manzaro, just like his teacher, Zingarelli, attributed great importance to the laws of traditional harmony. His strict adherence to these laws is evident in several documents.

Most telling is a much-quoted letter by Zingarelli written in 1835, inviting him to succeed him, because he did not trust any of the young Italians influenced by modern trends who were expected to take his post. This attitude is also documented in Manzaro's analysis of music by Monsigny and Grétry, his only published theoretical work.Footnote 52

Manzaro's influence on the society's teaching methods and goals was marked. Preserved in the society's library are documents of one of the composition competitions.Footnote 53 They include most of the compositions submitted and a printed booklet exposing the committee's remarks.Footnote 54 Observing them, one is impressed by the scholasticism of the comments, by a gravity that becomes a particular criticism of the light and frivolous style of many of the pieces.

In a pamphlet published on the occasion celebrating 50 years of the society, we read that in 1890 the music school had 171 students (nearly double that in previous years), seven studying harmony, 15 piano, four voice, 22 violin and viola, five violoncello, nine double bass, 11 brass, 11 woodwind, while 87 attended preparatory courses. (The members of the wind band were not included in those numbers). In all, 1,627 students had enrolled in the society's music school during its 50 years.

Training in wind instruments was of high quality, mainly because of the wind band that participated in many celebrations in the city, its members being exposed to frequent and hastily prepared performances. Up to this date, the best brass in the country's orchestras came from the Ionian Islands. Training in the instruments of the violin family began in the first year, but was often interrupted. In 1884 an effort to pay more attention to those instruments was financially supported by the government. Ernesto Centola, who had recently graduated from the Neapolitan conservatory, was invited to teach and organize ‘the bow-instrument section of the Corfu Philharmonic Orchestra’. Twenty-five students enrolled in his class (which probably included the viola as well). It is, no doubt, Centola's efforts that provided the library of the society with a disproportionate number of methods for studying the violin.Footnote 55

The piano was taught to a number of female students who attended the school as amateurs.Footnote 56 Some of them were also taught partimenti and have written piano music that survives. They are Amalia Genata, Françoise Courage and the most talented, Susanna Naranzi, a student of Manzaro, who published her piano pieces (short salon pieces, marches etc.) in Italy as well as in the Greek music periodical of Constantinople, Musike, in 1912 and 1913.Footnote 57

The names of all the staff in the nineteenth century have been preserved in the society's records and presented in various publications. Many of the names are Italian, but as was the case with Manzaro himself, many Greeks had Italian names, while many Italians had their names hellenized. Therefore it is difficult to identify all musicians active in the society and to determine their nationality.Footnote 58

Looking at the lists of the society's staff, one realizes that in most cases one musician would teach several subjects and several instruments, showing that specialization in performance had not yet reached this part of Europe. Another observation that reminds us how different music education and practice in Italian cities (and in Corfu) was from that in Paris and German cities, is that the number of double bass students was greater than that of the violoncello. This is connected to a practice that remained alive during most of the nineteenth century in Italian opera orchestras, whereby the double bass continuo players replaced the violoncello.Footnote 59 The name mentioned as a double bass teacher could well be Giuseppe Marangoni.Footnote 60

Gradually, the students of the music school participated in the opera orchestra, consisting mainly of visiting Italian musicians, while some of them became professors in the society and conductors of its ensembles. The names of the students participating in the orchestra appear in the opera's programme notes with expressions such as ‘primo clarino, bandista della Nobile Societa Filarmonica’ or ‘Allievo del Cav. N.C. Manzaro’ or ‘Socio Onorario della Filarmonica Corcirese’ or with works dedicated ‘alla Nobile Società Filarmonica di Corfu’. In the 1850s operas by Greek composers connected to the Philharmonic Society began to be performed on the San Giacomo stage.Footnote 61

Athens

In 1834 Athens took over as the country's capital from Nauplion (which had been capital since 1829, after Ægina first assumed that role in 1828). Athens would start to resemble a Western city in the 1870s, as its population grew then to around 65,000.Footnote 62 The early capitals were connected with the first governor of the state, Ioannis Capodistria, who, being a famous and successful politician in Russia, was called to govern Greece in 1828. Capodistria's policy in education was clear – to fight against illiteracy and for technical and professional schools. He established a fast and effective method of teaching in grammar schools, (advanced students training the beginners), a school and an orphanage in Ægina,Footnote 63 a military school in Nauplion, a church school in Poros and an agricultural school in Tyrins.Footnote 64

However, political change was to have a significant effect on pedagogical developments. In 1830, Britain, suspicious of Capodistria's connections with Russia (considered an imminent dominant force over the vacuum left by the Ottomans) had convinced the ‘protecting forces’ of Greece to turn the state into a kingdom. Then in 1831 Capodistria was murdered. In 1832 the Bavarian Otto (1815–1867) was enthroned as King of Greece and it was his idea to move the capital to Athens. In 1834 a large-scale construction plan was realized by German and Greek architects. The city's population and space developed, mixing within a few kilometres a diversity of cultures at different phases of development, living styles, nationalities, languages and idioms, moral codes and aspirations. At least up to the 1870s, the society of Athens was certainly distinct from those of all other European capitals.

Until his coming of age, Otto was replaced by a regency of three Bavarians, the first foreign ‘troika’ to govern the country. On taking the throne, Otto ruled as an absolute monarch until in 1843 he was forced to grant a Constitution. Throughout his reign he had the impossible task of keeping in balance the interests of the three powers ‘protecting’ and financing his kingdom, as well as the Greek political parties affiliated to each (the Russian, the British and the French). When, in the Crimean War, the British protected the Ottomans from the Greeks, Otto's reputation declined rapidly, and he was deposed in 1862.

The Bavarian court left no deep imprint on Athenian musical life. In fact, Otto was notoriously unmusical and suffered from defective hearing. In the royal palace there were frequent receptions where dances (waltzes, polkas and other contemporary dances) were performed. It is certain that the ensembles performing these dances were formed mainly by Greek or Italian musicians of the military bands who came as a rule from the Ionian Islands, and by the few German musicians employed in the royal court. No attempt by the court musicians to promote German music to the Athenians has been recorded. On the contrary, according to the historian Theodoros Synadinos, the first performance of German music in Athens was given by the Italian violinist and composer Pacifico Baldoni in a concert in December 1860. Baldoni and his piano accompanist, Ioannis Mindler, played a Mozart violin sonata. Being confronted with noisy disapproval, they changed their programme fast, finishing with popular tunes heard in the streets of Athens that saved them from the people's fury.Footnote 65

Indeed, in Athens there was a somewhat disorganized musical life, independent of music schools. One finds in the Athenian press after 1850 descriptions of concerts given ad hoc, mainly in hotels or in aristocratic houses as well as in the open air. This kind of activity was kept alive by foreign musicians (mostly Italians) who left their countries, inspired by professional musicians, to seek opportunities in musically ‘primitive’ lands.

The earliest organization known to have included music education in its programmes is Philekpædeutike Etæreia, which was founded in 1836 for the instruction of female school teachers.Footnote 66 An early music teacher there was Giuseppe Parisini, an Italian musician who had been a violinist-conductor of opera performances in some of the best Italian theatres.Footnote 67 In 1845, his son, Raffaele Parisini, succeeded him in this post. Raffaele appears from 1841 to 1844 in Corfu's San Giacomo as ‘primo violino e direttore d'Orchestra’, like his father.Footnote 68 He would become an important figure in music education in Athens. His arrival in that city was part of an increasing wave of mobility amongst musicians, which reached a climax after the union of the Ionian Islands with Greece in 1864.

Various people (such as Frederic Steven, Giuseppe Cæsaris, Giuseppe Liberalli, Alexander Augerinos, Julius Ennig) are present within a short time period in various cities (mainly Nauplion, Hermoupolis, Patras and Athens). The Italian Riccardo Bonicioli of German origin (Richard Frühmann) appears in Corfu and Athens, but also in Spain, Portugal, Russia and South America (Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires)!Footnote 69 Another group of Italians (like Napoleon Mifsud, Raffaele Ricci, Gaetano Foschini) sought opportunities in Smyrna and Constantinople before trying their chances in Athens.

To all those musicians, Athens, from the 1870s, became an attractive place to work. The governor Charilaos Trikoupis, taking advantage of world economic developments, improved the economic fortunes of the country and expanded its foundations. In 1876 the Stock Exchange of Athens was established, while the banks of the country multiplied. The road and railway network, as well as many harbours, were constructed and subterranean wealth exploited. Prosperous Greeks who had been living abroad were installed in their country, offering much of their wealth to the motherland, education being a priority.

Little has been written in systematic form about music societies in nineteenth-century Athens. This discussion, based on statutes, proceedings and official records and a comprehensive study of the press,Footnote 70 only claims to be a starting point for work in greater detail. The organizations that included music education in their activities and which affected musical life in Athens to a greater or lesser extent,Footnote 71 were either for church music or Western music. The former were influenced by Greeks in Constantinople, such as the Ecclesiastical Music Association (1874–89), the creation of the Constantinopolite Greek, Elias Tandalides. Interest in church music would expand greatly in the first decades of the twentieth century because those involved, having no contact with Westerners, were late to conceptualize Western music as a threat to their own music.Footnote 72 They considered unwise, the harmonizations of church music, which were very popular in the palace, in Greek communities in Europe,Footnote 73 as well as in some churches in the centre of Athens.Footnote 74

The most active groups promoting Western music were the Music and Drama Association of Athens (1871–), the Philharmonic Society Euterpe (1871–76), the Music Association Orpheus (1879–80), the Athens Philharmonic Society (1889–97), the Association of the Friends of Music (1892–96), the Athens Music Association (1894–95) and the Athens Music Society (1897–1904). They were all amateur associations; the only professional association (Association of Professional Musicians), founded in 1899, dissolved in 1901.

Music education offered initially by those groups aimed to prepare music ensembles for public performances. In many cases, youngsters first learned their part by ear; the notation and the theory of music was taught to them gradually to shorten rehearsal time. According to their statutes, all the societies mentioned above had music schools attached. Comparing them, it becomes evident that nearly all derived from a common model, the statute and the regulations of Corfu's Philhamonic Society.Footnote 75

All music societies divided the lessons offered into vocal and instrumental music. The instruments taught were strings (violin family only), woodwind and brass. Only the Philharmonic Society Euterpe and the Music and Drama Association had classes in keyboard instruments.Footnote 76 Some regulations determined the years required for the completion of studies. In Euterpe (where lessons were given for three hours per week), studies in voice lasted three years, while in instrumental music no limit was determined. Students judged competent in an instrument were allowed to follow two years of training in harmony; they were considered then able to compose.Footnote 77 According to a regulation of the Music and Drama Association, published in 1874, study of the viola, double bass and brass instruments was completed in three years, while that of other instruments and voice took four years.Footnote 78

Vocal training in the Athens Music Society aimed to prepare members of church choirs, as well as choirs in concert halls and theatres.Footnote 79 Singing lessons were offered only to boys and men and were graded into preliminary and applied; in the first, elementary theory was taught and vocal exercises practised, while in the second, choral songs were taught. The statute of the Athens Philharmonic Society mentions as an aim the training of opera singers and composers in order to create a Greek operatic repertory.Footnote 80

From the regulations of most societies concerning members of wind bands, it becomes clear that they were boys only, over 15 (or, in some exceptional cases, 12) years of age. They were distinguished into classes according to their musical ability (and, in a few cases, were paid accordingly). Analogous classes existed for members of the Athens Music Society's chorus consisting of the school's graduates; they were either first class (‘solistes’) or second class. Passing a test, amateur musicians or undergraduates were permitted to participate also in both the wind band and the chorus.

Among the societies mentioned, two made their presence known significantly in the musical life of Athens – the Philharmonic Society Euterpe and the Music and Drama Association. The former was founded in 1870 by young men of the city's elite, who had acquired a music culture in private or abroad. The society's aims were, according to its statute, the cultivation of musicality, the study and performance of music compositions and the teaching of music. Raffaele Parisini was the man who kept the society active and efficient. His death in November 1875 brought about its decline and dissolution the following year. Euterpe, under Parisini, had a choir of 40 members and a small mixed orchestra, which he had formed and trained on his own initiative and privately before 1870, incorporating them in Euterpe at its foundation.Footnote 81 These ensembles were much loved by the people of Athens, who attended their performances in gardens and squares. Their concerts included some very popular compositions by Parisini himself, the greatest hit being his ‘melodrama’ L'Arcadion, relating an heroic event during an unsuccessful revolution in 1866 in Crete, when still under the Ottomans.

The Music and Drama Association was founded two months after Euterpe's statute was signed (1 May 1871), on 15 July 1871.Footnote 82 This association had the support of members who were rich, well educated and well connected to politicians. The Conservatory of Athens, which began to give lessons in 1872, was the most important branch of the association, and it is up to this day one of the larger and better-manned music conservatories in Athens. Its first director was Alexandros Katakouzenos, who came from Odessa (where he was serving the populous Greek community), to direct the polyphonic choir of the royal church in Athens and offered his services to the conservatory.

In the first year 325 boys and 142 girls enrolled in the conservatory. Lessons were offered in singing, violin, flute and acting. In March 1873 a new class of singing was formed where 80 children from the Chatzecosta orphanage were enrolled. In the academic year 1874–75 two piano classes were established (one for boys, one for girls), both taught by an Italian with the rather appropriate name, Enrico Stancapiano.Footnote 83 On 28 January 1874 the first mixed concert was given by the students, the programme including two orchestral pieces from Italian operas. The rest were adaptations, transcription and compositions written by Katakouzenos for one or two interpreters.Footnote 84 In 1877 the conservatory gave its first diplomas. Up to 1880, twenty-one students graduated.Footnote 85

In those years the awareness of ancient Greek heritage was widespread amongst Greeks due to successful archæological excavations,Footnote 86 the organization of the Olympic Games in Athens in 1896 and the Olympiads that preceded them,Footnote 87 as well as the popularization of opinions expressed principally by Bourgault-Ducoudray about the resemblance of folk music to ancient Greek music. It is not an exaggeration to say that the most popular work (among the very few known) of Western Romantic music around 1890 in Greece was Mendelssohn's incidental music to Sophocles’ Antigone, op. 55,Footnote 88 and that thereafter the composition of music for ancient Greek theatre by Greek composers is a common and continuous enterprise. The prospect of the Olympic Games of 1896 caused a revitalization of cultural organizations during the entire decade and an inflation of pride. Indeed, feeling ran so high that in 1897 the Greeks became involved in a brief, ill-fated war against the Ottomans.

The most important product of this revitalization was the reform of the Conservatory of Athens in 1891.Footnote 89 It marked a great change in music education, a leap over the barriers created by the exclusive connection to Italian music culture, and the introduction to Greek music education of the programmes, the repertory and the requisites of German music academies and the French Conservatoire. The Conservatory of Athens received generous finance from Andreas Syngros (1830–1899), a banker in Constantinople who moved to Athens in 1871, founding there as well as in Thessaly, banks that attracted other prosperous Greeks from abroad, greatly contributing thus to the progress of the country.

Syngros was not the only wealthy Greek to give substantial donations to the conservatory. Although personally involved, he proposed Georgios Nazos as the appropriate person to carry through the reform. Georgios Nazos, coming from a rich and cultivated family, was sent to Munich to study and on his return became the director of the Conservatory in 1891, where he brought about radical changes. Many of the musicians who were taught under Katakouzenos were excluded from the staff. Katakouzenos himself resigned and died the following year.Footnote 90 In the first year of the reform, 169 male students and 113 female enrolled, but only 79 and 73, respectively remained up to the end of the year. Among the male students, 25 were orphans from the Chatzekosta Orphanage.Footnote 91

In 1892 a certain Moritz Unger was invited to teach violin; his efficiency was notable in the first concert by students to be open to the public, on 29 May 1893; it included works by Mozart, Beethoven, Fauré, Chopin, Haydn, Mendelssohn, Ries, Meyer and others as well as Pergolesi's Stabat Mater. The press was enthusiastic after the dress rehearsals, especially about the orchestra, composed by students, except for the violoncellos, the double basses and the violas.Footnote 92 In 1893, the pianist Eufe Empedokleous was the first to graduate from the reformed conservatory and the first female to be engaged in its teaching staff (the same year). ‘It is characteristic of the mentality in those days,’ writes a student in her diary, ‘that she was confronted with huge resistance by her family. In her home no one ever spoke about this matter … Nonetheless, her example was soon followed.’Footnote 93

In an interview to the daily newspaper Asty, on 27 July 1890,Footnote 94 Nazos spoke of his intention to bring to the conservatory good teachers from abroad,Footnote 95 and commented on those who spoke superficially about free tuition and a conservatory open to everybody. ‘The conservatory should not only care how to form musicians’, he said, ‘but also how they will live afterwards as professionals.’ Nazos appears to have been aware of the fact that the only professional opportunity available to the conservatory's graduates was a teaching position in the conservatory itself. In a way, he was admitting that the conservatory was an establishment that catered for people who did not need to earn their living. Often criticized for elitism, and unable to remedy the situation, Nazos turned the defence to offence, in a letter published in the newspaper Hestia in 18 March 1899. He wrote of the government's obligation to support all music societies and military bands in the country, to establish symphony orchestras in the large cities, and one opera company in Athens. ‘This is a way to reach the people’, he says, ‘not by offering music education free in the conservatory of Athens.’Footnote 96

Epilogue

Greek state officials’ lack of concern for music education, implied by Nazos, is a constant in the history of recent Greek music. Not until 1981 (when Greece became a member of the European Union) did a Greek governor show active interest in the subject.Footnote 97 Some of the causes of this are related to the antitheses that characterized music education in nineteenth-century Greece, antitheses that are highlighted in our description of the work done in music educational institutions in Constantinople, Corfu and Athens. Music of the Greeks in the nineteenth century consisted of two different traditions: music of the Greek Orthodox Church, the notation of which, reformed in 1814, was widely disseminated during the entire century, and Western music. Among all the areas of the Greek diaspora, it was mostly in Constantinople that the first was cultivated, while Western music was taught and performed in Corfu. Those two musical cultures coexisted in Athens, the capital of the new Greek state, where however, social and political conditions did not favour any interest in music education before the 1870s. In that decade, the favourable international economic circumstances and the enlightened policy of prime minister Charilaos Trikoupis, permitted the establishment of the nation's first professional associations to take on systematic training in music education. Since the policy of the new state aimed at the Westernization of Greek society, Western music prevailed. It was taught in Athens, initially by mainly Greek and Italian musicians from the Ionian Islands. Because of those islands’ close relations with Italy, the music taught and performed there emphasized Italian opera, while the masterpieces of the great German composers (from Beethoven to Wagner) were excluded. Their works would be taught and performed in Athens only after the reform of the Athens Conservatory by Georgios Nazos in 1891, a reform that would synchronize music studies in Greece with Western Europe's, but, given the absence of professional organizations for music performance, would mainly attract the high bourgeoisie and be criticized for elitism.