Fairground Echoes

In 2011 I travelled with a group of friends to the Great Dorset Steam Fair: a multi-day event held near Blandford, Dorset, celebrating the UK's industrial heritage and dedicated to the preservation and exhibition of bygone technologies. Launched in the late 1960s – as many of the technologies in question were becoming obsolete – the Fair has grown into one of the largest events of its kind in the intervening half century.Footnote 1 But its founding ethos persists. When the Italian historian of popular spectacle, Giancarlo Pretini, wrote in 1987 of an English penchant for ‘recurring gatherings of classic cars and historical machinery [including] automobiles, locomotives, steamrollers, fire engines, steam trucks and Fairground Organs’, he may well have had the Great Dorset Steam Fair in mind; certainly, his description chimes with my own impression of the event, several decades later.Footnote 2 Between the tractor-pulling contests and the vintage fairground rides and the strong local cider, though, it's the last item on Pretini's list that stands out most prominently in my memory. Huge mechanical organs – hulking machines in ornate painted finery, or decked out in lights that cycled through kaleidoscopic displays of pattern and colour – stood at intervals throughout the fair. Foursquare renditions of well-known musical selections were made visible as well as audible, in some models, by the automatic mechanism that played the percussion and pipe instruments displayed prominently in their casing. Like Charles Ives's converging brass bands, the instruments battled for auditory supremacy as one moved between them, but amid the cacophony I remember being struck by a mighty rendition of ‘My Heart Will Go On’, Celine Dion's mega-hit theme song for the 1997 blockbuster Titanic.

Large mechanical organs have been capturing the attention of gawping passers-by for close to two centuries, though for a significant portion of that time they would have been understood not as a nostalgic heritage act but rather as a common source of popular entertainment. There is some uncertainty as to when they were first placed in fairgrounds. Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, author of several monographs on mechanical instruments, suggests that fairgrounds employed large ‘show organs’ from the mid-1870s onwards, initially as a stand-alone feature to attract custom (a ‘mechanical barker’, in Ord-Hume's words); only later were they integrated into stalwart fairground attractions such as merry-go-rounds, re-imagined as an underscore for the cycling lights and repetitive motions of the rides.Footnote 3 But today these instruments are probably best known for their association with silent film exhibition at the turn of the twentieth century.

Although the public debut of the Lumière Brothers’ cinématographe, which took place on 28 December 1895 at the Grand Café in Paris, often stands symbolically as ‘the birth of cinema’, it is more accurate to say that moving picture technologies first coalesced around that time, when several like devices – including Thomas Edison's kinetoscope, the Lumière cinématographe, and others besides – were developed and exhibited to great acclaim. In relatively short order these technological marvels were absorbed into the repertoire of travelling showmen, who exploited the entertainment potential of the nascent cinematic medium in cafés, town squares, and crucially in fairgrounds, where film exhibition took its place as one attraction among many: not for nothing did the film historian Tom Gunning dub this early period of cinematic history, running from c. 1896 to c. 1906, ‘the cinema of attractions’.Footnote 4 Given that mechanical organs were already by this point a fairground fixture, there is no doubt that such instruments were a common feature of the soundscape of early cinema, with which they became closely entwined in the popular imagination. Indeed, for Ord-Hume ‘only with the coming of the bioscope did the instrument really emerge as a “fair organ” and attain the peak of its perfection’, and it is certainly true that the biggest automatic organs ever made were intended specifically for use by fairground film exhibitors.Footnote 5

Perhaps unsurprisingly, many scholarly accounts of the fairground organ describe it as an early kind of musical accompaniment in silent cinema; Febo Guizzi's survey of the instruments employed in Italian popular and folk music traditions is typical in this respect, noting in passing ‘the application of certain of these complex instruments to the musical accompaniment of silent cinema’.Footnote 6 In contrast, film historians tend to be more cautious. The Italian scholar Aldo Bernardini, whose pioneering work on il cinema ambulante (‘itinerant cinema’) has included detailed study of fairground film exhibition, has pointed out that ‘we don't know whether the organs which … adorned the façades of the most elaborate booths were purely for “external use” or if they were also used to accompany the films themselves’.Footnote 7 Rick Altman, working in a different national context, has similarly noted that mechanical sound-reproduction devices such as organs, pianolas and gramophones were often deployed outside American storefront cinemas in the 1900s to attract custom, without being understood as ‘accompaniment’ per se.Footnote 8 This uncertainty is hardly surprising. Fairground film exhibition, like the fairground itself, was by its very nature a peripatetic and decentralized phenomenon, whose imprint on the historical record is patchy at best. Its sounding presence is even more poorly attested. Gauging the contributions of mechanical organs to the early cinematic experience presents significant methodological challenges, and in this respect Gian Piero Brunetta's evocative summation of the fairground cinema phenomenon writ large is aptly applied to fairground organs more specifically, when he writes that ‘their cries, their sounds appear … like the signs and residual traces of a vanished civilization, which we study with the impression of using tools similar to those employed by archaeologists’.Footnote 9

We are therefore fortunate to have a detailed account of fairground cinema written by an Italian writer named Luigi Caglio. Though published long after the fact, in the 1950s, Caglio's recollection of one particular fairground cinema operator active in Northern Italy, the Kühlmann family, is notable for the emphasis it places on the mechanical organ as a key component of the experience:

The façade of this cinema had all the necessary features to enchant not only those of us who were actually children, but also the child who is hidden within most adults and who never really dies. To the left a huge organ, of Germanic origins naturally, delighted the ears and eyes of the audience with an abundant medley of tunes, and along with it a decidedly ornate structure and décor made one's eyes widen in shock. The Kühlmanns' organ was … a manna for penniless friends of music and, what is more, it paired the visual element with various tunes [motivi] that it spread around the square thanks to a mechanized figurine who rang a bell and some little drummers [tamburini] who every now and again underlined with their movements the articulations of the rhythms.Footnote 10

Caglio's account is particularly striking in that he doesn't mention the notion of ‘musical accompaniment’ at all. Rather, he draws attention to the organ's role as an attraction in its own right, whose ‘abundant medley of tunes’ represented a considerable draw in an era before sound reproduction had become truly widespread. What's more, Caglio emphasizes the strongly audiovisual nature of the organ's allure: the music is enhanced both by the bombastic decorative scheme and crucially also by a series of additional automata, in the form of miniature mechanical figurines of musicians who mime playing the music emanating from the machine's pipework.

Later historians have tended to reinforce this interpretation of the organ's appeal. According to Pretini, by the end of the nineteenth century ‘the organ, of sometimes enormous dimensions, had almost become an autonomous spectacle’,Footnote 11 while Antonio Latanza avers that ‘part of their attraction, therefore, derives from the spectacular nature of their exhibition, whose visual component cannot be ignored’.Footnote 12 What happens, therefore, if we take the primal scene of early cinema evoked in Caglio's recollection at face value, and examine the organ's musicking not as one more sonic supplement to an essentially visual phenomenon (i.e. the film) but rather as a distinct form of audiovisual display: one whose roots, like those of cinema itself, reach deep into the nineteenth-century technological and cultural substrate? If, as Deirdre Loughridge has persuasively argued, ‘not only the proliferation of lens and image-projection technologies, but also their encounters with music began far earlier than narratives of audiovisualization and histories of multimedia have allowed’, what do we gain by considering the history of the organ itself as an intrinsically audiovisual phenomenon?Footnote 13

These are the questions to which the remainder of this article is devoted. In the process of answering them, as my focus to this point on Italian authors and Italian sources has hinted, we uncover a story in which nineteenth-century Italy plays a surprisingly prominent role. This is partly because the instrument that later became known as the ‘fairground organ’ is widely held to have been invented in the 1840s by an Italian, the Modena-born inventor and entrepreneur Ludovico Gavioli.Footnote 14 The organ-manufacturing firm Gavioli founded shortly thereafter linked Italian enterprise and large mechanical organs in the public imagination for well over half a century, even if the company, like many other instrument manufacturing firms founded by emigrant Italians, was founded and flourished elsewhere on the Continent (in Paris, in Gavioli's case).Footnote 15 Indeed, despite the subsequent flourishing of native manufacturers of large mechanical organs in countries across Europe, such instruments were also associated with Italy in a broader discursive sense, in written sources published both on the Italian peninsula and further afield. For this reason, I find it helpful to borrow a scheme from the Finnish media historian Erkki Huhtamo, who, in his reconstruction of the evolving cultural milieu of the moving panorama – a crucial audiovisual medium of the early to mid-1800s – considers the ‘painted panorama’, the ‘performed panorama’ and the ‘discursive panorama’ as three separate, if overlapping, fields of historical inquiry.Footnote 16 Similarly, I consider the fairground organ from three interrelated angles: the organ as an invention with specific technological underpinnings; the organ as it was exhibited to an increasingly broad audience; and finally the organ as a discursive object, shaped by and contributing to broader ideas about popular culture and its merits relative to more refined artistic practices. Through this tri-partite approach, the ‘show organ’ becomes a prime lens through which to examine elements of Italian musical culture during the 1800s that might pass unnoticed in studies focused on more conventional trappings of musical culture (works, composers, opera houses, and the like).

What follows is in several parts. First, I will briefly discuss the historiography of the prehistory of cinema, dwelling in particular on the influence of the methodological approach known as media archaeology. Second, I will examine the underlying mechanism, physical appearance and musical signature of large mechanical organs, particularly in the earliest instruments created by Gavioli and his eponymous organ manufacturing company, before turning to the ways in which the latter were exhibited in the streets and squares of cities across Italy and Europe. Gavioli's organs are described in mid-nineteenth-century sources in a strikingly consistent way, and these descriptions support the idea that organ exhibition was an inherently audiovisual, and inherently public-facing, phenomenon from the very first – long before the organ's eventual introduction to fairgrounds. Third, I consider the reception of Gavioli's instruments in sources from across the latter half of the century, drawing out the tendency to insist on the mechanical organ's Italianness. I argue that the discursive slippage between the fairground organ and the barrel organ, or ‘Barbary organ’ as it was often called, reveals the class-based assumptions guiding the reception of automatic instruments and their attractive qualities in educated circles. Finally, I turn to an Italian source from the late 1800s, Il ventre di Milano, whose evocation of the Milanese ecosystem of organ exhibition and consumption resonates productively with the commercial exploitation of cinema in its early years. On this basis, I suggest we might profitably invert the formula that sees fairground organs primarily as a backing track for the exhibition of early cinema, and instead see early cinema as the latest visual enhancement to grace the exhibition of the automatic organ.

Archaeologies of Film (Sound)

Ever since the 1970s, when the study of so-called early cinema took off in earnest, historians have uncovered countless links between cinema in its first few decades and the popular culture, entertainment habits, scientific mentalities and technological fixations of the preceding decades. Even those scholars apt to see in the advent of cinema a quintessential marker of advancing twentieth-century modernity – cinema as the ‘eye of the century’, in the words of the Italian film scholar Francesco Casetti – acknowledge the many continuities between the pre-cinematic and the cinematic.Footnote 17 And the study of silent film sound, exemplified in particular by the work of Rick Altman, has been essential to a long process of defamiliarization thanks to which early film is no longer understood as a ‘primitive’ stage in a linear ‘evolution’ of cinema – from scientific marvel to the storytelling medium we remain familiar with today – but instead seen as a historically situated phenomenon whose development was shaped by a range of historical actors, competing technologies and cultural preoccupations of the fin-de-siècle.Footnote 18

In this regard Brunetta's archaeological metaphor, quoted above, resonates with the aims of a methodological approach that has significantly shaped the fundamental transformations in the historiography of early cinema and its prehistory over the last 50 years: media archaeology. Scholarship in this vein, as Emilio Sala has put it recently, is determinedly anti-teleological: it holds that ‘the present is not an outcome of the past’, and that it is important to ‘identify missed opportunities, unrealised possibilities, and alternative trajectories’ in our study of media in history.Footnote 19 Early cinema was one of several important ‘new’ media of fin-de-siècle modernity around which the media-archaeological approach developed, famously considered alongside the gramophone and the typewriter in a landmark study by Friedrich Kittler.Footnote 20 Setting aside our knowledge that cinema did, eventually, become ‘the eye of the century’ allows us to embrace the alterity of the cinematic medium in the years around 1900; to acknowledge the manifold forms the moving-picture phenomenon assumed in its early years and the various directions it might have taken; and to trace the multiple lineages of influence on the new medium, a complex inheritance that binds it tightly to the cultural milieu from which it emerged. For the film historian Thomas Elsaesser, who has written prolifically on the subject, the development of cinema in the late 1800s is unthinkable without the prior development of a wide range of technical antecedents, extending well beyond the usual suspects: experiments with motion photography, magic lantern shows and the like. The celluloid film strip itself, for instance, was an outgrowth of the explosives industry in the 1860s; the ratchets and gears of early motion-picture cameras innovative adaptations of comparable mechanisms found in bicycles, sewing machines, and machine guns; and so on.Footnote 21

Early cinema remains today an important strand of media-archaeological thought. Over the past several decades, as Jussi Parikka has observed, it has enabled scholars to produce ‘not only film histories, but histories of audiovisual culture in which film, understood in the mainstream sense, was only one possible end result from the various strands, streams and ideas that formed the (audio)visual culture of, for instance, the mid and late nineteenth century’.Footnote 22 And as Parikka's repeated emphasis on audiovisual culture suggests, it is a methodological stance that could fruitfully be applied to sound in cinema as well. The parentheses around ‘(audio)’ in his second use of the term, however, are telling. They speak of a certain reluctance (in the face of the aforementioned methodological challenges) to trace the sounding branches of cinematic genealogy with as much enthusiasm as their visual counterparts – notwithstanding the significant strand of media archaeology that seeks to excavate the sonic, above and beyond its instantiation in particular technological forms.Footnote 23 For instance, in Siegfried Zielinski's classic text Audiovisions – which regards film as merely an ‘entr'acte’ in a longer history of audio-viewing – there remains a focus on devices for visual display, with musical accompaniment presumed as standard but never discussed.Footnote 24 And Elsaesser's call to treat the phonograph as an important strand of cinematic prehistory (building on Edison's famous declaration that with the invention of the Kinetoscope he had wanted to ‘do for the eye what the phonograph had done for the ear’) remains in his work one provocation among many.Footnote 25

This tendency to emphasize the visual even in studies of cinema's prehistory as an audiovisual medium is part of my motivation for bringing a media-archaeological approach to bear on the instrument emphasized so strongly in Caglio's account of fairground cinema exhibition: the fairground organ. Providing an exhaustive account of this instrument (as Erkki Huhtamo has done for the moving panorama, for instance) lies beyond the scope of this article. Fortunately, such an enterprise is unnecessary, because unlike the moving panorama (which fell between the cracks of scholarly accounts of other more celebrated phenomena) there is already a sizeable literature on automatic instruments of all kinds, including music boxes, player-pianos, musical clocks, and naturally the mechanical organ.Footnote 26 Much of this scholarship, as Stephanie Probst has recently observed with respect to the player-piano, has been led by communities of collectors and enthusiasts of such instruments, typically writing outside the formal academy;Footnote 27 in the case of the mechanical organ in its various guises, including the fair organ, Ord-Hume's exhaustive treatment remains authoritative.Footnote 28 Because of this existing foundation, in what follows I will take the opportunity to think more speculatively about the relationship between fairground organ over its decades-long history and the cinematic medium that emerged when the former was arguably at its zenith. Drawing on Loughridge's exploration of the audiovisual cultures of German-speaking lands in the eighteenth century, I aim to examine the organ as one key node in a nineteenth-century Italian audiovisual culture. Like Loughridge, I do not seek to frame the organ as a form of ‘proto-cinema’ per se, but rather as one more device – though, crucially, a musical one – that provided materials, both physical and discursive, contributing to the development of cinema as an audiovisual form.Footnote 29 Like magic lantern shows, in other words, the exhibition and commercial exploitation of mechanical devices such as the organ involved the combination of sonic and visual information long before the cinema came along. And in an Italian context specifically, where – as we shall see – the characteristic association of the organ with the Italian operatic repertoire comes strongly to the fore, it becomes clear how these longer audiovisual lineages constitute a key site of music-historical inquiry in their own right.

Monster Organs

The inventor of the fairground organ is generally acknowledged to be one Ludovico Gavioli (1807–1875; sometimes written Lodovico), born in Modena to Giacomo Gavioli (1786–1875), himself a blacksmith and carpenter turned inventor and clockmaker.Footnote 30 Ludovico inherited his father's facility for mechanical wizardry, and from a young age showed a knack for constructing increasingly elaborate mechanical devices, from innovative clock escapements to musical automata. Unlike his father, Ludovico saw the potential for showmanship inherent to such objects. His reputation was first established in the 1830s by a life-sized automaton of the biblical King David playing the harp, which seems – even in an age that was, as Terrance Riley has argued, thoroughly habituated to the spectacle of complex automata – to have made a significant impression on contemporary observers.Footnote 31 Perhaps David's appeal, beyond the skill with which his mechanism was constructed, lay in the fact he played Desdemona's Act III aria from Rossini's Otello, thus juxtaposing the sacred and the secular, Old Testament piety and modern Rossini fever. Yet the alleged fate of this automaton – lent to a travelling showman who promised to exhibit the device on a lucrative tour of Europe, but who never returned it – also reveals Ludovico's lack of business sense, which would afflict his commercial dealings throughout his life.Footnote 32

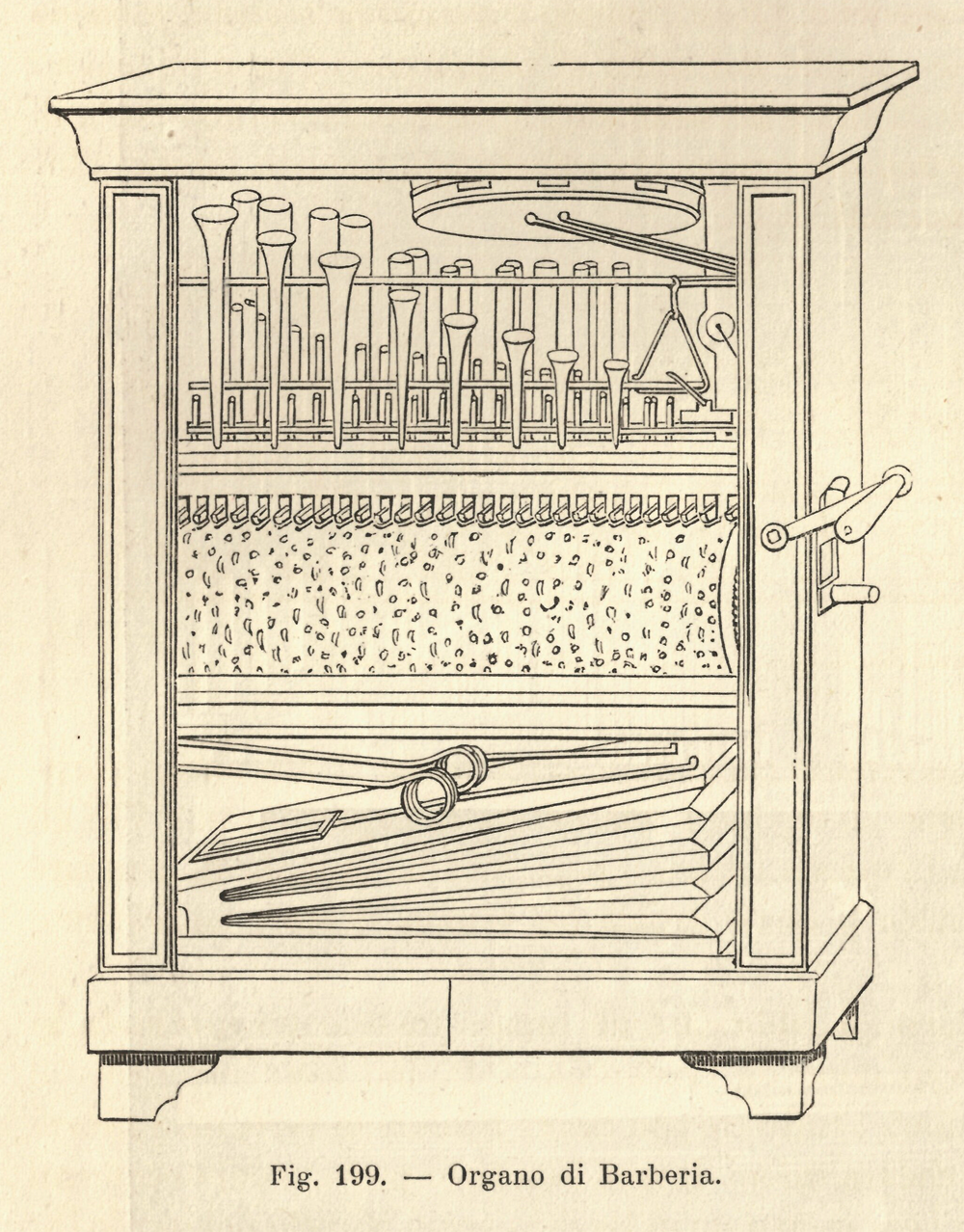

Throughout his career Gavioli fils was drawn to experiment with the mechanism animating the device known in Italy as the organetto or organo di Barberia: the portative barrel organ, which Gavioli père considered unworthy of his attention given its indelible association with lowly street musicians.Footnote 33 Inside the decorative casing of such instruments lay a complex mechanism activated from the outside by a hand crank: this crank operated a set of bellows that maintained the air pressure in the organ's pipework, while rotating a cylinder or barrel upon which raised metal pins and bridges encoded the music played by the organ. As the pins turned past the instrument's keyframe, they raised keys corresponding to particular pipes, enabling air to flow through them and pitches to sound (see Fig. 1 for a diagram of the interior mechanism of such an instrument). Organs constructed using this barrel-and-pin mechanism had a long history in Europe, including, as Loughridge has shown, as a musical counterpart to optical spectacles such as magic lantern shows throughout the eighteenth century; in this sense Gavioli's device was neither particularly new nor, really, an ‘invention’.Footnote 34 Rather, his principal innovation was to refine the mechanism and eventually to expand it to gargantuan proportions, to create instruments in which the barrel was connected not only to large arrays of keys and pipes (sometimes many hundreds) but also to a more or less elaborate series of percussion instruments, thus enabling the recreation of music originally conceived for orchestral forces.

Fig. 1 Interior of a portative barrel (‘Barbary’) organ. Illustration from Francesco [Franz] Reuleaux, Le grandi scoperte. II. Le forze della natura e modo di utilizzarle, 2 vols., vol. 2, trans. Corrado Corradino (Turin: Unione Tipografico-Editrice, 1887): 210.

Gavioli built an early version of this expanded mechanical organ in the early 1840s. The Panarmonico (sometimes Panarmonio), as it was called, made a huge impression on the Modenese elite when it was unveiled in 1843. Modena's leading citizens published a volume of literary and poetic tributes to Ludovico's genius, while the Modenese royal family rewarded the inventor with a gold medal.Footnote 35 A minute description of the instrument commissioned by Modena's leading learned society, the Regia Accademia di scienze, lettere ed arti di Modena, gives us some concrete details of what Gavioli had achieved.Footnote 36 The Panarmonico had no fewer than 240 keys, such a large number that they were divided between two key frames, each connected to its own rotating barrel; an additional mechanism ensured both barrels rotated at exactly the same rate. The same mechanism allowed for three distinct rotation speeds, in turn enabling fine gradations of tempo and a more musical performance. Because such gradations were no longer solely encoded in the distances between the metal pins on the barrel, Gavioli could also fit more pins on each barrel and reproduce longer pieces of music than comparable devices to that point. Gavioli chose particular metal alloys for different kinds of pipes, and he refined the shape of the pipes to better mimic the timbres of the flute, oboe, trumpet, trombone and so on, both as solo instruments and in choir. As a result the instrument was able to render famous overtures by Mercadante and Rossini in vivid orchestral detail: to quote Luigi Francesco Valdrighi, the author of a survey of Modenese instrument manufacturers published in 1884, Gavioli's Panarmonico ‘demonstrated that it was possible to build a mechanism so fine as to render, as though by a full orchestra, the introduction to William Tell, including the solos, the storm, the passage for trumpets, the double-time section, and also the finale of Act III of Mosé [in Egitto] in all their lovely effects’.Footnote 37

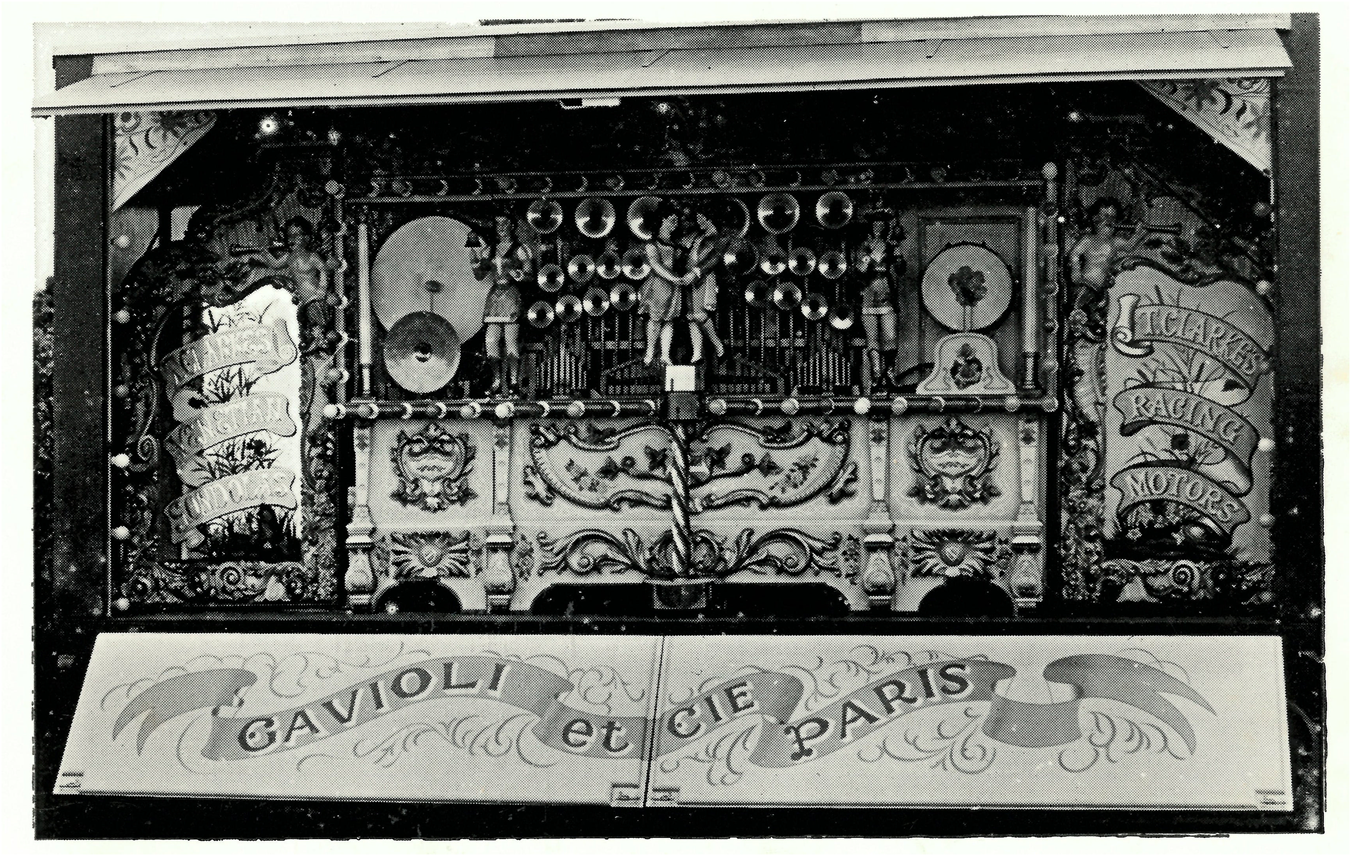

In view of these various refinements, the author of the Accademia's report on Gavioli's organ could only remark in wonder that ‘to our knowledge no other manufacturer has ever achieved such precise results … this machine [constitutes] the most perfect example of this genre ever produced by human artistry’.Footnote 38 The wealthy patron who had commissioned the device from Gavioli, however, refused to pay the exorbitant cost when it was finally finished.Footnote 39 While shedding no clear light on the immediate impact of this turn of events, one of Gavioli's nineteenth-century biographers, Alessandro Spinelli, suggests that it may have been the impetus for the inventor to leave Modena for Paris, in search of ‘a larger market for his inventions, and a more intelligent and refined clientele’.Footnote 40 From 1853, Gavioli settled permanently in the French capital, and though the inventor continued to develop new musical and mechanical devices throughout his life, the self-named firm that he established in Paris, Gavioli & Cie, would become best known for the design and manufacture of large mechanical organs, a reputation it kept until the beginning of the next century. After Ludovico's death in 1875, the Gavioli company was inherited by his son Anselmo, who continued to innovate: it was Gavioli & Cie that first switched, in 1892, from encoding musical notes on the by-now-antiquated barrel-and-pin mechanism, turning instead to long strips of punched cardboard, folded concertina-style into ‘books’ that the organ ‘read’ in order to activate the organ mechanism (hence the name ‘book organ’ bestowed on the instrument in English).Footnote 41 Similarly, it was the Gavioli company that first integrated into its instruments arrays of coloured lights, whose circuitry was controlled by the same book mechanism. But after Anselmo's death in 1902 the Gavioli firm went bankrupt, due to a mixture of mismanagement and misadventure, leaving the market to be dominated by a bevy of rival Continental firms led by emigrant Italians (e.g. Gasparini), native French firms (Limonaire), and businesses established by former Gavioli employees (Marenghi).Footnote 42

Let us return, however, to the 1840s. Much like the very similar orchestrions that emerged around the same time in German-speaking lands, the Panarmonico – which seems to have been a one-off – was theoretically intended as a source of parlour music in an aristocratic household. But the instruments Gavioli began manufacturing in Paris – which he dubbed the Stratarmonica – were from the first intended for public exhibition in city streets and squares. We can begin to understand the impact of this new form of street music from contemporary descriptions of Gavioli's organs. Though these tend to converge on similar points throughout the company's sixty-year history, it is perhaps helpful to start with the neutral accounts of the device found in certain mid-century reference works. For instance, the entry for the term ‘organetto’ in an Italian encyclopaedia of 1862 contextualizes Gavioli's invention in a longer history of the barrel organ:

It is a case more or less large, more or less rich in ornament, containing several mechanisms, from which in combination, given the right conditions, one obtains sweet and harmonious sounds. Initially small in size and limited in range, gradually the portative organs grew, and now gigantic versions are manufactured that are either placed on a special horse-drawn cart, or placed permanently in parlours. Lately the Modenese Gavioli reached the height of perfection in this genre of mechanical art. In Piedmont they make many such instruments, and of good quality.Footnote 43

A dozen years earlier, in 1849 – just a few years after the instrument's debut – a French manual of organ manufacturing provided a more detailed account of the Stratarmonica's appearance and mechanism:

This large instrument, which appeared for the first time in Paris in May 1848, takes up an entire carriage drawn by a horse. It is about three metres high; a gallery running the length of the façade contains some musician automata who seem to play musical instruments whose effects are produced by the interior mechanism and which are animated by the motor that activates the cylinders and bellows.Footnote 44

From these more objective descriptions we can begin to see that Gavioli's organ did not appeal to its public through sonic means alone. What seems to have captured the imagination was the organ's great size, and the fact that as a result it had to be mounted on a special horse-drawn cart – something mentioned again and again in descriptions of Gavioli's instrument, even several decades later. ‘Who does not remember Gavioli’, wrote the author of an 1876 monograph on the history of the piano, ‘with his large organ mounted on a cart that resembled an orchestra?’Footnote 45 In very similar terms, the aforementioned Valdrighi wrote that ‘Gavioli, with his organ with little musical automata [automi sonanti], placed on a cart drawn by a horse, drew large crowds: and the name of our Modenese compatriot was for a time on the lips of all of Europe and the Americas’.Footnote 46 It is worth pausing briefly to consider the curious role of the horse in accounts of Gavioli's instruments. On the one hand, the horse was clearly as much part of the attraction as the instrument itself; yet for all that the horse was necessary for the organ's exhibition it is always implicitly figured as external to the functioning of the organ's ‘automatic’ mechanism. That is, the equine labour required to move the instrument (much like the human labour required to pump the bellows) is simultaneously foregrounded and obfuscated.

In terms of the impact the Stratarmonica had on the urban public in its first appearances, Ord-Hume has drawn attention to a highly melodramatic account of the instrument's debut in London, published in the Illustrated London News in 1846 alongside a lithographic illustration of the imagined street scene (see Fig. 2). This column, unlike the encyclopaedic entries cited above, makes no pretence of objectivity. On the contrary, its description of Gavioli's ‘Monster Street Organ’ is embedded in a humorous diatribe against the daily torture that ‘Savoyard organ grinders’ impose on the urban soundscape:

here comes a Monster Street Organ to add to our daily torture. Our artist has resolved that our eyes shall be saluted with its aspects as well as our ears. Look at it and tremble, amateurs and artists! It is from the prolific manufactory of Gavioli, of Modena; and it cost, as the grinder-in-chief assured us, upwards of £150. Here is the march of Street Music; a locomotive Brummagem organ, drawn by a real horse, and exacting two men to develop its orchestral resources.Footnote 47

Despite the evident slant to the writing, there is much to glean from this description. We can perceive the inherent drama of the organ's staging before the public, with the ‘real’ horse again singled out: and beyond this, the ways that the instrument itself was built to ‘salute the eyes as well as the ears’, to be enticing from a visual perspective. As the column further outlines, the internal mechanism was at least partially visible from the outside, so that the public could see the instruments being played; another mid-century source singles out the pipework imitating trumpets, flutes, and clarinets as well as a range of percussion instruments on display, including a snare drum (tamburino) and the more exotic Turkish crescent (cappello cinese).Footnote 48 And of course, there were the additional figurative automata, one of the key charms of Gavioli's organs beyond its status as an enormous automaton in and of itself. Whether described as ‘cardboard figures’ or ‘moving automata’ or ‘mechanical dancers’, it is clear that the figures moved – likely in time with the music – thus drawing on a longer tradition of automata animating, for instance, the chiming clocks installed in church towers.

Fig. 2 ‘The Monster Organ’, illustration from The Illustrated London News 9/242 (December 19, 1843): 397. Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

What form these automata took in the original Stratarmonica is not clear, given that no instruments from this period survive directly. The illustration in Figure 2 shows a line of relatively large figurines representing musicians, playing appropriately sized instruments. The figures have a general air of exoticism, from the pointed hats and loose robes (suggestive of Orientalist stereotyping) to what may be a deliberate depiction of dark skin tone – though this may represent the illustrator's license, drawing on a visual imaginary of exoticized automata rather than first-hand observation of the device. Somewhat incongruous, too, is the prevalence of wind instruments arrayed around the large bass drum, which are suggestive of the band rather than the orchestral sonorities Gavioli took care to reproduce. Regardless, musicians certainly appear to have been a common theme in instruments produced later in the century. Photographs of Gavioli organs from this time typically show two or more automata arrayed in a line along an ornate, faux-Baroque architectural façade, often featuring a central baton-wielding figure flanked by supporters carrying pipes, drums or bells (see Fig. 3).Footnote 49 Present-day video footage of preserved organs in action, meanwhile, feature automata who follow a limited set of scripted movement (moving their heads from side to side, striking a bell held in their hands, and so on).Footnote 50

Fig. 3 Photograph of what may be one of the oldest fairground organs in Britain (anonymous, 1960s). Print in author's collection. At time of being photographed, the Gavioli instrument pictured belonged to the Gladiator Club in Redruth, Cornwall, and still retained its original barrel mechanism. Subsequently it has passed through several changes of ownership; in the late 1980s it was enlarged and converted to a book mechanism by organ builder Andrew Pilmer. I am grateful to Adam Tyler-Moore of the Gavioli Organ Trust for this information.

Ultimately, of course, this feast for the eyes was intended to act in concert with the music reproduced by the Stratarmonica. This raises the question of what miniature musicians on Gavioli's instruments actually ‘played’. Ord-Hume points out that the Gavioli family was musical in its own right, and that Ludovico and his children composed various pieces to grace their mechanical instruments. In a general sense, however, instruments of this nature – from organs to music boxes to chiming clocks – were typically endowed with a range of popular musics. Dance music was one important strand of this repertoire, and Gavioli organs commonly played the mazurkas, galops and waltzes of the day.Footnote 51 Other forms of popular music native to the Italian peninsula, such as the Neapolitan song tradition, may also have featured. Anita Pesce notes that there are examples of Neapolitan songs being built into music boxes and automatic organs as early as 1823, when a Viennese organ was installed in the Bourbon royal palace in Caserta; the organ played a range of music, including ‘a good many opera melodies, several dance tunes, and a few “folk arias”’ – including early versions of evergreen Neapolitan classics such as ‘Te voglio bene assaie’.Footnote 52

Undoubtedly, however, the mainstay of the mechanical organ repertoire was Italian opera, and for Roberto Leydi this type of dissemination is one of the few ways in which opera could genuinely be understood to function as a sort of popular music during the nineteenth century (in Italy and beyond).Footnote 53 Beyond the generic (and dismissive) references to ‘Bellinian and Rossinian melodies’ in the Illustrated London News column, specific extracts mentioned in connection with the Gavioli street organ across various other mid-nineteenth century sources include the overture to Rossini's Guillaume Tell (1829) and the prelude to Act III of Mosè in Egitto (1818); the overture to Mercadante's Elena da Feltre (1838); the ‘Cavatina’ from Verdi's Ernani (1844; likely Elvira's Act I aria ‘Ernani, involami!’), the finale of Act III of I due Foscari (1844), and the ‘Brindisi’ from Macbeth (1847).Footnote 54 In the context of the original Panarmonico, a one-off technological marvel commissioned by an aristocratic patron, one can readily see how the recreation of the colours of the opera house – specifically, recent works by prominent Italian composers that Modena's leading citizenry might plausibly have seen in the theatre – could have added to the appeal of these objects for a refined audience. The continuing presence of opera excerpts in the repertoire of the public-facing Stratarmonica and subsequent street organs, however, speaks to the melodic facility of Italian opera that was key to the genre's wider popularity. Regardless, this tendency to prioritize recent hits from the operatic literature seems to have remained the Gavioli strategy for decades. In a 1903 column dedicated to open-air music, Claude Debussy, writing under his acerbic pen-name Monsieur Croche, commented on the hidebound repertoire of the mechanical organ: ‘is it really enough’, the composer exclaimed,

just to have made organ rolls of the Entr'acte from Cavalleria Rusticana, the ‘Valse bleu’, and a few other masterpieces in the last years? … Come, M. Gavioli, can you not see where your duty lies? M. Gailhard did not hesitate to put on Pagliacci at the Opéra; well, hurry up and make instruments that can play the complete Ring!Footnote 55

(Italian) Street Music

In all likelihood this concentration of Italian operatic excerpts in the mechanical organ repertoire was responsible, at least partly, for the widespread perception that the instrument itself was an Italian phenomenon. The fact that the renowned Gavioli firm had Italian origins doubtless also contributed, and the firm's fame and brand recognition was significant enough to have left linguistic traces (according to Latanza, the standard English word for a fairground organ operator by the end of the 1800s was ‘gaviman’).Footnote 56 But perhaps even more important was the organ's multiple genealogical links to a related instrument: the portative barrel organ, or Barbary organ as it was also called in various countries (French: orgue de Barbarie, Italian: organetto di Barberia). As we have seen, Gavioli's street organ employed an adapted, enlarged version of the mechanism contained within the smaller instrument: this is the lineage acknowledged by the Italian encyclopaedia entry of 1862 cited above. But many nineteenth-century sources also noted another connection, which is that the Barbary organ itself had allegedly been invented in the 1700s by an Italian – by another Modenese, no less – named ‘Barberi’, whose name, via processes of linguistic corruption, was transferred to the instrument itself.Footnote 57 Those same sources also took care to note that this genealogy was highly dubious, but in reprising the connection, they nevertheless traded on the implied lineage of Italian innovation that connected Gavioli to an illustrious forebear. Some writers even suggested that the Gavioli organ had not only succeeded the Barbary organ but supplanted it wholesale. ‘A strange thing!’ remarked Francesco Valdrighi, ‘that by enlarging it, [Gavioli] almost made disappear the old invention of Barberi, his compatriot from the preceding century, erroneously known by the inanity orgue de Barberie, which had until that point exclusively delighted (?!) the public of the streets’.Footnote 58

Both the Italianness of Gavioli's instrument and its connection to the Barbary organ are drawn together in an article published by a Parisian correspondent for the Modenese periodical L'indicatore modenese in 1851.Footnote 59 This article reprises and translates two other articles about mechanical organs, originally published in French, which confirm the Italian reputation attached to such instruments and give some fascinating glimpses of the socio-economic world they (literally) travelled in.Footnote 60 The first translated piece gives a by-now familiar description of the family of organs in question: ‘there are several types of organ: the Barbary organ, whose false and strident tones irritate the nerves; the intermediate organ which is two feet to two-and-a-half feet in length; and the Italian organ [l'organo d'Italia], mobile, shaped like a large wardrobe, in which there move small cardboard figures’.Footnote 61 Of the ‘Italian organ’, which is to say Gavioli's novel street organ, the author continues by noting that it is ‘very pleasing to the eye, and not displeasing to the ear’ (assai gradevole all'occhio, e non dispiacevole all'orecchio) on account of its stereotypically Italian repertoire; and that the Italian organ (unlike, presumably, the smaller barrel organ) does not enter internal courtyards and people's homes, but instead stays in the public space of city streets and town squares.

The second translated column, though written in a lightly satirical tone, expands on the dramatic impact Gavioli's instruments had upon their arrival in the French capital: they caused all the city's Barbary organs to fall silent. According to the author of this second article, the introduction of ‘monster-organs, drawn by a horse, endowed with ringing, noisy harmonies and enriched by the play of small mechanical dancers’, incited jealousy in the existing population of itinerant barrel organists, for whom the Gavioli organ represented stiff competition.Footnote 62 The author reports that this competition was strong enough to provoke riots and fistfights between the different tribes of mechanical organ operator; and perhaps more plausibly, that Barbary organs were recalled by manufacturers across Paris in order to endow the smaller instruments with a new repertoire of tunes, the better to recapture the attention of the fickle listening public. In so doing the author gives us an insight into the commercial ecosystem that even in 1851 already existed around reproduced music: the poor barrel-organ operators whose livelihood depended on the goodwill of passers-by; the manufacturers who made money by leasing technology rather than selling it; the fierce competition that could arise between rival media and the profound threat that new media could represent to even well-established patterns of cultural exchange.

Barrel organs and Gavioli's larger street organs, then, were not mutually exclusive in the public imagination – which is hardly surprising, because even if the Stratarmonica emerged from a world of technical innovation and mechanical wizardry that elite audiences could admire without reservation, in its usage it tended to compete directly with the instrument that had inspired it and which it now threatened to displace. But the problem with acknowledging the close ties between the two kinds of street music is that the comparison necessarily introduced elements of the social that elite audiences were apt to ignore, if not to demean. Itinerant street musicians were an inescapable feature of the urban life of cities in Italy, and also across Europe and North America.Footnote 63 The operators of these instruments (and many other similar mechanical instruments, from hurdy-gurdies to mechanical pianos) were often destitute and were therefore engaged in a highly sonorous form of begging, one whose sonic presence had been decried by well-heeled denizens of European cities from the seventeenth century onwards.Footnote 64 What is more, by the mid-nineteenth century begging with instruments was itself often perceived to be an Italian phenomenon, because, as John Zucchi has discussed, many of the operators were children from impoverished Italian families, dispatched to major metropoles like Paris, London and New York in order to be indentured to anonymous masters for whom they were forced to earn money, often by playing musical instruments.Footnote 65 (Like the horses pulling Gavioli's instruments through the streets, the Italian child and his or her forced labour thus becomes an essential – external, living – component of the barrel organ's supposedly automatic mechanism.) For this reason the smaller portative instrument and its less-than-savoury reputation was likely lurking in the reception of Gavioli's organ from its very inception, even as its creator was being hailed by his literate compatriots as a standard-bearer of Italian enterprise and even ‘Italianità’.Footnote 66

Indeed, the barrel organ led a busy life in mid-century literature as a rhetorical trope. Not all figurative uses of the instrument were necessarily malign. In one 1858 source, for instance, the barrel organ is employed as a metaphor for the circularity of existence, for the mundane and repetitive everyday: ‘the world [is] nothing other than an enormous barrel organ, built in colossal proportions by an eternal maker, on which nine hundred million little human figures spin constantly in an interminable waltz, at least until it pleases the player to stop turning the handle, or until the bellows that set the mechanism in motion break’.Footnote 67 More often, however, the discursive organ was shaped by its associations with the people who were its typical operators, usually functioning straightforwardly as prejudiced shorthand for the lower classes. Take, for instance, an issue of the humoristic periodical Pasquino published in 1863, which outlined a list of ‘things that are easy – much too easy – to find in Turin’.Footnote 68 Almost all the phenomena cited are the visible and audible presence of the lower classes in the Savoyard capital, from ‘fake’ beggars asking for money, to poor children selling posies for a song, to a band of drunkards whose revelry disturbs the night-time silence; also cited, naturally, is ‘a Barbary organ, and an itinerant singer or two who pierce your ears’.Footnote 69 And with the noisy signature of the organ readily stamped with negative class associations, it was but a small step to disparage the people who were attracted to the organ's display as much as that of the people operating the instrument.

This disdain for both operator and audience is abundantly obvious in the mid-century sources I have been quoting, leaking out in small, performative demonstrations of class superiority at every turn. The incredulous punctuation embellishing Valdrighi's observation that barrel organs had ‘exclusively delighted (?!) the public of the streets’ prior to Gavioli's invention of the fair organ is just one example; Angelo Catelani's casual dismissiveness when he notes that the ‘self-propelled automata that appear on [Gavioli's] organs have elicited a thousand wide-eyed reactions from idiots and non-idiots alike’ is another.Footnote 70 It is a tendency taken to extremes in one notable description of the barrel organ found in a popular introduction to mechanical devices by the German engineer Franz Reuleaux, published in Italian translation in 1887. At the end of a brief section dedicated to mechanical musical instruments, Reuleaux summarily dismisses the legitimacy of the barrel organ as a token of musical culture: ‘Hand-cranked organs, improperly known as Barbary organs – insofar as they are allegedly called Barberi organs after Barberi, the Modenese who invented them – are not really musical instruments in the strict sense of the phrase, given that to play them requires not even a shadow of talent or of an artistic sensibility’.Footnote 71 He continues in a revealing chauvinistic vein: ‘They are in use principally in certain countries – such as Russia – where contact with more civilized peoples has developed in the native population a taste for music, without their having – generally speaking – the necessary cultivation to satisfy this taste of their own accord’.Footnote 72

As the century wore on, therefore, the broader antipathy towards the barrel organ gradually encompassed the Gavioli street organ. The esteem initially granted the latter as a grandiose automaton waned, and the Gavioli instrument became simply another source of the same category of urban noise pollution: it became less obvious that writers invoking ‘the barrel organ’ or ‘the Barbary organ’ were necessarily referring to the portative instrument rather than Gavioli's organ of the streets and piazzas. Tellingly, Debussy's sardonic engagement with Gavioli in the Monsieur Croche column begins with the declaration that ‘no one in France cares any more for the barrel organ!’, collapsing the two instruments into one obnoxious whole.Footnote 73 In fact, as Ord-Hume has discussed, the persistent campaign against automatic music in urban areas on the part of ‘the aristocratic and wealthy who had no use for that class of entertainment’ began, by the end of the 1800s, to have more tangible effects in the form of what were effectively zoning laws.Footnote 74 Legislation combatting the ‘murder’ of renowned musical works by organ grinders, as contemporary discourse frequently had it, typically designated areas in which street musicians could legally operate, or created licensing systems that similarly limited the number of musicians who were permitted to ply their trade.Footnote 75 There is in this pattern of dissemination a striking resonance with the early reception of cinematic technology: acclaimed first as the latest miracle of modern science and exhibited to educated audiences, before retreating to the fairground as an itinerant spectacle consumed by a mass audience, and eventually considered an unruly phenomenon in desperate need of regulation by civic authorities. As Huhtamo notes, ‘film culture did not inherit only material features from earlier shows; also the imaginary around it accommodated pre-existing discursive formulas’.Footnote 76

Sounds of the Underbelly

Can we draw this link with cinematic dissemination out further? Il Ventre di Milano: Fisiologia della capitale morale (1888) is a multi-authored collection of short chapters aiming to capture the experience of urban life of Milan, Italy's financial and industrial capital.Footnote 77 Like other similarly named volumes,Footnote 78 the book claims to present a more authentic portrait of the phenomenon at hand: as the anatomical metaphors in its title suggest, by uncovering the Milanese ‘underbelly’ that other descriptions might prefer to pass over in silence, the city's underlying ‘physiology’ is revealed. One aspect of this physiology is the activity of street organists, to which Aldo Barilli, one of the volume's many contributors, dedicates a chapter.Footnote 79 Barilli's brief and whimsical account derives some of its effect from the nostalgic evocation of a past era: the time before street organs were banned from the area delimited by Milan's elaborate system of canals, or navigli, which surrounded the city centre on all sides. As with similar proscriptions elsewhere, banishing organs beyond the cerchio dei navigli was an act ultimately born of class prejudice, as the disruptive presence of the organs and their generally lower-class operators was eliminated from the area most likely to be populated by Milan's well-heeled citizenry. But the memories of their contributions to the urban soundscape were still fresh.

In one sense, Barilli simply confirms many of the details we have already encountered in earlier mid-century sources (in fact, he plagiarizes some of his description of the large Gavioli street organ directly from contemporary sources).Footnote 80 Gavioli's organ is once again described as being drawn by a horse or an ass (ciuco), and requiring the presence of three human operators taking it in turns to crank the handle powering the mechanism; again in addition to ‘genuine organ pipes’ its percussion-heavy instrumentarium is said to include bass drum, cymbals, sistrum (sistri) and chimes (campanelli); once more we see a reference to the dancing automata displayed on the organ's façade ‘stopping people in their tracks, open-mouthed’.Footnote 81 Similarly, the classed rhetoric around the street organ's typical operators and listening publics flows easily from Barilli's pen: the proscription of street organs within the city walls is described as ‘a boon for all those who work with their head and for all lovers of music's dignity, which is so often murdered by those tone-deaf [organ grinders]’.Footnote 82

Yet, despite retreading many of the byways of earlier organ rhetoric, Barilli's description zeroes in on a wealth of new details. For instance, he evokes different kinds of engagement with Gavioli's instruments, beyond the gaping mouths and wide eyes of the crowds that passed them on the street. There are the individuals who give itinerant organists money to move along, but also those who pay the organists to stay put – particularly, writes Barilli, in streets ‘where there were a few households peopled with young ladies, who improvised dance parties among themselves to the organ's tunes’.Footnote 83 More striking still is his observation of the audiovisual incongruities that could arise from the combination of the figurative automata and the music emerging from the instrument's pipework: ‘Who has not seen the pantomime of the great Napoleon bidding his generals farewell before departing for Elba, but gesturing in time to a mazurka by Marco Sala, who at that time hadn't yet been born?’Footnote 84

This single sentence is highly suggestive. To begin with, it suggests that the figures depicted in automaton form on the casings of Gavioli organs were not restricted to abstract archetypes – musicians, dancers, perhaps commedia dell'arte characters and the like – but also encompassed famous historical personages, presumably recognizable to a broad audience. At the same time, the image of a mechanical Napoleon gesturing in time to the music strongly resembles the conductor automaton described by Caglio. One therefore suspects that casing automata in Gavioli's organs usually moved according to a handful of standardized patterns of movement, into which figures representing different characters were installed and changed through the instrument's life. Above all, Barilli's use of the word pantomime places the organ in dialogue with other popular forms of entertainment during the nineteenth century, including pantomime and melodrama, which combined movement and gesture with pre-existing music of a popular stamp. Similar practices would come to characterize musical accompaniment in cinemas just a few decades later, as scholars of early film music have amply documented.Footnote 85 In fact, given that early cinematic actualités often captured contemporary celebrities (royalty, for instance) and that some of the earliest cinematic narratives, however brief, featured famous historical figures, one can readily perceive continuities between the spectacle mounted on a fairground organ casing and the spectacle of the moving images projected beside it. In Italy as elsewhere, a public who had seen Napoleon move to modish mazurkas and operatic hits would later see on-screen characters in films accompanied by waltzes from trendy operettas and, again, well-known selections from the operatic literature.

Strengthening this cinematic connection is Barilli's evocation of the economic organization of organ exhibition in Milan. As Ord-Hume and Zucchi have shown, many street musicians could not afford to own their own instrument: indentured child musicians, for instance, were typically given one by a controlling padrone who expected the organ, and any takings, returned by the end of a day's work. And as the Parisian journals from the 1850s I cited earlier demonstrate, even if their labour was not formally constrained by an indenture, poor organ-grinders might still be obliged to rent organs from the manufacturers, who would presumably demand a substantial cut of the day's profits in return for the privilege of using the instrument (and theoretically for servicing the instruments and periodically changing the repertoire with which they were endowed). Gavioli street organs, however, were so large and expensive that the leasing model must have been widespread. In Milan, Barilli notes, there were (at least before the prohibition on the instruments took effect) at least 15 companies leasing organs of all different types, from large street instruments through to humble portative versions.Footnote 86 Even more specifically, Barilli writes, albeit with a strongly anecdotal flavour, of one Signora Cecca – ‘queen of the organ-leasers’ – who apparently owned no less than 12 large street organs, ‘from which she extracted ten to fifteen lire of profit per day’.Footnote 87 In a piquant detail, she even has a retainer acting as an enforcer: in the event that a hapless organ operator absconds with the instrument they have leased, Felice sets out to find them armed with a club. Guided by his ears, he listens first for the far-off sounds of an organ tune. Then, using his knowledge of the music that Signora Cecca's organs played, and of the particular timbre of individual instruments, Felice tracks down the perpetrator and ensures the safe return of the business's key assets (and the stolen profits).

Changes in licensing laws have been the ruin of entrepreneurs throughout the history of entertainment media, and the prohibition of organs in central Milan brought Signora Cecca's franchising empire to an abrupt close. But what is striking about her story is the picture that emerges of a highly structured economy of street music exhibition, even if operating in a legal grey area, one which makes comparison to the nascent film exhibition sector a few decades later irresistible. Signora Cecca was neither a manufacturer of mechanical instruments, nor their operator: she was a middle-woman, with the means to invest in the expensive devices as assets to be exploited through the labour of others. Her business model therefore anticipates the eventual formalization of the film industry into distinct sectors of production, distribution, and exhibition, having begun its life dominated by travelling cinematographers who made and showed their own films. Similarly, Signora Cecca apparently dominates one end of an organ exhibition sector: the premium end specializing in the largest, most elaborate, and most expensive instruments. The mid-market and lower end of the range, one presumes, are the domain of the other 14 organ-leasing companies mentioned by Barilli. That is, a broad spectrum of the market is catered for, much as film exhibition would eventually diversify into luxe ‘first-run’ venues and dingier second- and third-run halls.

Audiovisual Legacies

The links between street and fair organs in the nineteenth century and fairground film exhibition, then, are plentiful. It is not just that large mechanical organs happened to have become a fixture in fairgrounds when cinema began to make a home there, and that organ music thus became a mainstay of the early cinematic soundscape by happenstance. Rather, the well-developed economy around the public exhibition of mechanical instruments in the nineteenth century provided yet another clear model for how new technologies like cinema could be exploited. This is not to discount the long and storied history of visual spectacles being exploited by travelling showmen, such as magic lantern shows, panoramas, and the myriad optical toys that make up the detritus of nineteenth-century visual culture: obviously the latter influenced the creation and the dissemination of the new cinematic technologies developed in the 1890s. Still, it is notable that the itinerant exhibition model that sprung about immediately around early cinema might plausibly have trodden the same routes taken by itinerant organ-grinders, making the rapid cross-fertilization between organ exhibition and film exhibition perfectly understandable in response. Large automatic organs had always included ample visual display in addition to their melodic resources, and at the turn of the twentieth century motion picture photography was an up-to-minute visual spectacle that could fulfil a comparable function admirably. Sound, in this perspective, was an important part of the growing commercial exploitation of cinema from the beginning, insofar as the organ's audiovisual pleasures had been consumed for many decades already before the cinema came along, thus establishing expectations that the new medium would offer an ‘integrated’ audiovisual spectacle of its own.

Ultimately, what this exploration of Gavioli's automatic organs indicates – their mechanism, their deployment in streets and fairgrounds, and their cultural life as a sonic marker of Italianness both within Italy and elsewhere in Europe – is the importance of considering musical artefacts when putting together a ‘sonic archeology’ of early cinema.Footnote 88 In an Italian context, much remains to be done. But even this brief tour of some byways of nineteenth-century musical culture shows that the perspective of early film exhibition opens fruitful avenues for further exploration, tracing new patterns in familiar narratives of operatic hegemony. Well-worn tropes of Italian opera's widespread popularity, often evidenced by opera's frequent reproduction on mechanical instruments such as the barrel organ, acquire new layers when we understand how the Italianness of the trope resided not just in the music or in the operators of such instruments, but in the instruments themselves. The rich history of Gavioli street organs, long before they became fair organs and eventually bioscope organs, highlights the importance of considering audiovisual relationships not only in the unfolding of early film history, but also in the construction of the historical sonic cultures in Italy that shaped the emergence of cinema on the peninsula. Indeed, it cautions us against exploring alternative sites of sonic culture (such as the fairground) in isolation, instead prompting us to take as a starting point the fluidity of sonic practices across a variety of media. That is, if scholars of Italian music of the Ottocento are increasingly apt to leave the opera house behind, Italian cinematic prehistory calls them to step into the piazza; to wander outside the city limits; to visit the fairground.