Introduction

The particular role assigned to Italians in European history has ensured that the myth of a regionalist and rural Italy still prevails, a land of home-loving and only mildly aggressive ‘good people’. This myth has been the subject of occasional studies related to the construction of colonial empires and racial theories. For the past 20 years, the construction of the notion of race in the Italian context, and particularly in the Fascist period, has generated the interest of historians and historians of science (Israel and Nastasi Reference Israel and Nastasi1998; Maiocchi Reference Maiocchi1999), who were until then mostly focused on Nazi Germany, relegating Fascist Italy to the status of a totalitarian regime which was imperfect and unachieved (Milza Reference Milza2008). Important works have broken a long historiographical silence (Del Boca Reference Del Boca1992; Palumbo, Reference Palumbo2003) and called into question the widespread notion of the alleged ‘indulgence’ of the Mussolinian regime (Bidussa Reference Bidussa1994; Del Boca Reference Del Boca2005) thanks to the analysis of the complex entanglement of colonialism with the construction of both Italian identity and racial alterity (Burgio Reference Burgio1999; Pogliano Reference Pogliano2005; Deplano and Patriarca Reference Deplano and Patriarca2018; Aramini and Bovo Reference Aramini and Bovo2018). Some of these studies have notably described in what manner such debates concerning identity are connected to the ‘southern question’, that is to say, a bipolarity between the North and South of Italy, pitting the presumed Aryan North against the Mediterranean South, and the need to proclaim the purity and the superiority of an imaginary Italian race in order to legitimate its colonial conquests.

It is nevertheless striking that these scholarly works are mostly restricted to the historical field, with rare exceptions such as the exhibit ‘La Menzogna della razza. Documenti e immagini del razzismo e dell'antisemitismo fascista’ (Centro Studi ‘F. Jesi’ 1994) which showed that the discourse on the racial question during the Fascist period did not confine itself to politics but permeated all facets of culture, anthropology and science, as well as art and literature. The catalogue published on this occasion also unveiled the extent to which racism and colonialism went hand-in-hand, through the radicalisation of representations of alterity during the war of Ethiopia. Despite the pioneering character of this exhibition and catalogue, the studies which associate visual and material culture with racial issues are few and only cursorily address the question of race (Triulzi Reference Triulzi and Del Boca1997; Reference Triulzi and Burgio1999; Casti and Turco Reference Casti and Turco1998; Angeli et al. Reference Angeli, Boccafoglio, Recchia and Zadra1993). The works which explicitly treat visual representations mainly deal with the use of pictures as a pedagogical tool (Gabrielli Reference Gabrielli, Deplano and Pes2014; Reference Gabrielli2015). The same lacunae are also evident in the field of anthropology. While some scholars have underlined the importance of photography in the construction of alterities, the images published in anthropological studies have not to my knowledge been the subject of any analysis, and the question of facial casting from nature has rarely been dealt with in such studies (Piccioni Reference Piccioni, Sebastiani and Loriga2019; Moggi-Cecchi Reference Moggi-Cecchi, Moggi Cecchi and Stanyon2014).

However, a closer examination of the formation and circulation of images displaying bodies will lead, in my view, to some reflections on the role of visual representations in the construction of a mass racial ideology. The hypothesis behind this essay is that these images may be understood as agents that transform what are in fact inconsistent and vague notions of identity and race into concrete and effective ontologies, both in the scientific field and in the popular understanding. It is immediately clear that the formation of stereotyped images of African peoples in the popular imagination is fed by scientific discourses that those images in turn feed back into. This dialectical movement is at the very heart of anthropology, since, just at the time when this discipline was becoming institutionalised, the theories it defended were based on a visual corpus to compensate for scarce scientific material. Only a study that takes these two dimensions into account – the scholarly discourse and the popular discourse – can thus accurately reflect the processes of ‘othering’ and racialisation that mark nineteenth and twentieth century Italian history (Stoczkowski Reference Stoczkowski1994; Latour Reference Latour1996). Representations of black bodies will therefore not be considered here as mere documents or instruments of propaganda, but as forms in action (Bredekamp Reference Bredekamp2005) that give visibility, fixing and make ‘objective’ (Daston and Galison Reference Daston and Galison2007) the classifications of humanity. It is in this sense that the image generates reality, or agency (Gell Reference Gell1998), for it functions like the institution of a piece of evidence. As many historians and philosophers – Michel Foucault, Maurice Olender, Ann Laura Stoler, W.J.T. Mitchell – argue, what gives racism its fearsome efficiency is the immediate relationship that it claims to establish between the seen and the unseen. To reconstruct the ideological impact of these representations, it is necessary to analyse the context of their production as well as the networks of dissemination and reception they were inserted into, for ‘the image does not serve as evidence in itself, it is inscribed in an exterior device which guarantees its truth’ (Guichard Reference Guichard, Dubuisson and Raux2015). It is for this reason that it is vital to analyse these representations and their critical reception with the aid of the corpus of texts that accompany them, in order to reconstitute the ‘horizon of expectation’, that is, interpretations by the public in a given timeframe.

The focus of this study will be a defining historical phase of Italian colonialism, between the proclamation of the Empire in 1936 and the early 1940s. After the conquest of Ethiopia, a series of laws ‘inaugurated specific forms of racist discourses and practices peculiar to the late Fascist period’ (Sorgoni Reference Sorgoni, Grillo and Pratt2002, 1). These laws prevented the indigenous people from obtaining Italian citizenship, denying them access to bars, cinemas and public transport, and they furthermore prohibited mixed marriages because miscegenation was considered a factor in the degeneration of the purity of the Italian race. These policies anticipated the publication of the Manifesto of the Race (1938) and gave Italy a ‘sad primacy’ since it was the first country to adopt a racial law in its colonies (from 1937) punishing all relations of cohabitation between Italians and African women with a prison sentence (Labanca Reference Labanca2000).

If one considers that the foundation of its first colony in Eritrea dates back to 1890, one may see that the history of Italian colonialism is distinguished by an accelerated hardening of the racial discourse. The late Unification of Italy in 1861 launched a drive for conquest and an equally late participation in the scramble for Africa. This explains the intense mobilisation of an African iconography in a nation of recent formation in order to make its colonial aims attractive to public opinion as quickly as possible (Surdich Reference Surdich1982; Sega and Magotti Reference Sega and Magotti1983; Triulzi Reference Triulzi and Del Boca1997). In 1895, in the magazine Critica Sociale, one reads that Africa is ‘after maccheroni [the famous type of pasta], the most popular thing there is in Italy’; the Italians ‘read neither books nor newspapers’, but ‘when it comes to Africa, the sphinx or the Black Continent, as the Italians call it with a little contempt, they gladly spend a penny on the gazette and want to know everything’ (Zolfanello 1895). Newspaper illustrations play a leading role in the mass dissemination of images of an Africa of the imagination at the very moment when Italy is engaged in its military actions (Zagatti Reference Zagatti1988; Nani Reference Nani2006; Manfren Reference Manfren2019) and thus compensate for its weak military and institutional preparation. They are characterised by an ‘exotic’ and ‘orientalist’ narrative, terms that refer to the stereotyped imagined world dissected in Edward Said's famous book Orientalism (Reference Said1978).

Later, under the Fascist regime, the visual corpus of stereotyped images of African populations disseminated by the illustrated press gradually gave way to representations of black bodies, and especially of black faces, which were highly essentialised and racist. While, between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century, anthropological photographs from the first colonies in Africa were primarily circulated among a limited number of specialists (Labanca Reference Labanca1988; Palma Reference Palma2002; Reference Palma2005), their widespread dissemination began from the mid-1930s. This period is characterised by a kind of ‘osmosis’ between the three forms of racism that Nicola Labanca defines as ‘institutional’ racism, ‘political’ racism, and ‘mass’ racism (Labanca Reference Labanca2000, 413). In the following pages, I will study this shift towards generalised racism by focusing on a heterogeneous visual and material corpus at the intersection of material culture and visual studies: the facial casts exhibited in the Italian museums of anthropology and during the Mostra delle Terre d'Oltremare which took place in Naples in 1940, the images of the infamous magazine La Difesa della razza (1938–43) as well as the visual material – advertising and record covers – that accompanied the success of the popular song Faccetta nera. The common motif in this heterogeneous material is that of the face. This essay focuses on the ideological reasons behind the widespread dissemination of essentialised representations of the facial features of colonised populations and the manner in which these become effective instruments of racial propaganda. The face is understood here as ‘the basic form of human recognition’ and therefore as an ‘inherently political’ entity that stands at the base of a critical turn in body and race studies (M'charek and Schramm, Reference M'charek and Schramm2020).

Casts from nature: anthropological artefacts for mass production?

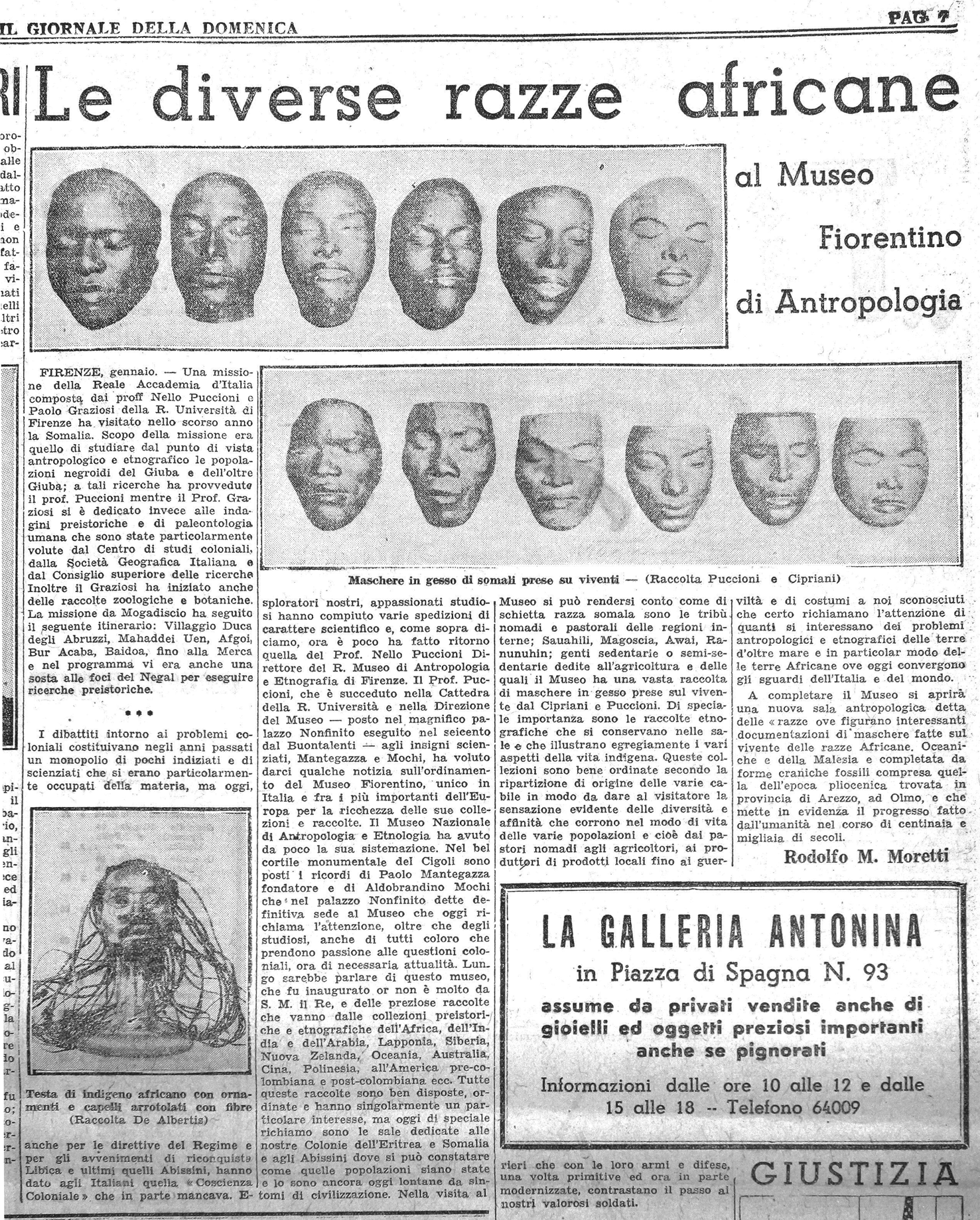

In 1936, the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence opened ‘a new anthropological room dedicated to “races”’ (Moretti, Reference Moretti1936). Several newspaper articles (Figure 1) described ‘a large display case [where] coloured plaster casts of an incredible number of human faces are arranged. These are “masks” taken from living people by Elio Modigliani in south-east Asia, by Nello Puccioni in Somalia, and by Lidio Cipriani in other areas of Africa and India’ (Visoli Reference Visoli1936). A journalist described this room as follows: ‘They are the faces and expressions of “our relatives” however distant, faces and expressions – I have had this sensation many times – that awaken something like vague memories in our inner depths of people known once upon a time … Perhaps our subconscious goes back to the origins? Perhaps’ (Visoli Reference Visoli1936). This commentary testifies to the visual reception of these casts perceived as the demonstration of an evolutionary and racist conception of humanity, where non-Western populations are relegated to the status of men from the origins.

Figure 1. Article by Rodolfo Moretti, ‘Le diverse razze africane’. © Il Giornale della Domenica 12–13 January 1936: 7.

This exhibition opened its doors a month before the proclamation of the Empire by Mussolini on May 9, 1936. It was organised by Nello Puccioni (1881–1937), the then director of the Florentine Museum, and Lidio Cipriani (1892–1962), who succeeded him in 1937. Both were familiar with the practice of face casting. Puccioni assembled a collection of 40 casts in Somalia while, between 1927 and 1938, Cipriani systematically set about producing an extensive collection of 350 specimens from different ethnic groups (Eritrea, Libya, Ethiopia), the originals of which are currently kept in the Museum of Anthropology and Ethnology in Florence.

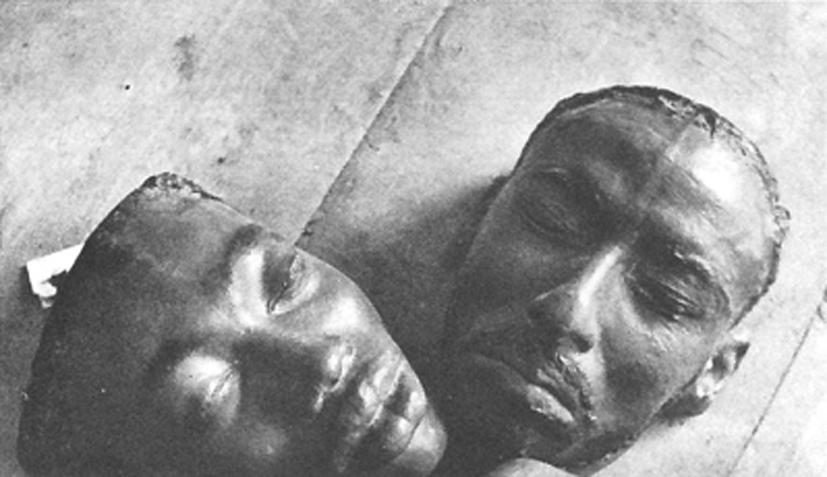

The casts were made in two stages: in the field the impression was made from an individual lying on the ground. This was an invasive practice inflicted on native populations whose acquiescence was won by means of barter – or mere lies (Feldman Reference Feldman, Edwards, Gosden and Philips2006). Its violence is evident in the photographs that show Cipriani accompanied by his collaborators applying a layer of quick-setting plaster on the faces of the models (Figures 2 and 3). In In Africa dal Capo al Cairo (Reference Cipriani1932a), Cipriani describes this practice as follows:

I made eleven facial casts of Bushmen with plaster. I was determined to achieve this at all costs, but one must not think this was a simple matter. We have to operate on people whose language we do not know and convince them to allow their faces to be covered with plaster diluted in water and to let it stay, without making any movement, until it has hardened. And nevertheless, I managed to succeed, to the great surprise of my fellow travellers who recommended caution, fearing that I would be hit at any moment by a poisoned arrow if the Bushmen were not pleased with the operation. I do not deny I sometimes took care to demonstrate, as if in play, the effects of my gun on a plant, but I never needed to use any intimidation. On the contrary, offerings of tobacco and cakes were always sufficient means to make me loved by the Bushmen, who always behaved with me like good, well-behaved people (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1932a, 167).

Figure 2. Lidio Cipriani moulding a facial cast on a living individual, Zululand (Kwa-Zulu Natal), South Africa, 1927 (1/2) © Museum of Natural History of Florence, Anthropology and Ethnology Section, Photographic Archives, no. 4506.

Figure 3. Lidio Cipriani moulding a facial cast on a living individual, Zululand (Kwa-Zulu Natal), South Africa, 1927 (2/2) © Museum of Natural History of Florence, Anthropology and Ethnology Section, Photographic Archives, no. 4507.

In 1932, the anthropologist notes in his travel diary in the Fezzan region that to counter ‘the great resistance on the part of the chief Touareg Cheikh Hamma Ben Mohamed’, he made him believe that he would make ‘a bust to his glory like that of Mussolini to show the Touareg in Italy’ (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1932b). Reproducibility was not the only feature these artefacts shared with the statues of the Duce. For one of the reasons for the anthropologists’ passion for this practice, from the mid-nineteenth century onwards, was the possibility of reproducing these artefacts identically, which then enabled their widespread distribution. Back in metropolitan Italy, the original cast made in the field made it possible to manufacture a mould in white plaster – a negative – which in turn could be used to reproduce other copies – positives – which were then coloured with a brush on the basis of the chromatic scale established by the doctor and director of the Museum of Anthropology in Berlin, Felix Ritter von Luschan (1854–1924).

Anthropologists considered these facial casts to be authentic documents of distant populations. This supposed authenticity explains their great success at a time when the definition of ethnic ‘types’ and ‘races’ became a major issue of anthropology. These artefacts were sources of study shared by the different schools of anthropology emerging in Europe, but they were also exhibited in museums in order to reconstitute at the metropolitan centre an experience of otherness that could replace in situ observation (Sysling Reference Sysling2015; Driver Reference Driver and MacGregor Brill2018). Showing these faces in display cases as the scientific proof that ‘races’ existed was in line with the historical practice of setting up live-human exhibitions – also known as ‘human zoos’ (Blanchard, Boëtsch and Snoep Reference Blanchard, Boëtsch and Snoep2011; Abbattista Reference Abbattista2013; Belmonte Reference Belmonte2019).

Anthropological casts are located at the intersection of art history and anthropology. Together with funerary and religious wax casts, they constitute a class of objects which, as representations, invite aesthetic analysis. The technique of the imprint was passed down through the ages. In Roman antiquity, it was used for funerary masks, and in the Middle Ages for votive purposes. Then it was rehabilitated during the Renaissance to preserve ancient architectural forms and to make statues and death masks for the richest families. It is to the Tuscan painter and writer Cennino Cennini (1370–1440) that we owe the first reflections on this process. The last nine chapters of his Libro dell'arte (c1400) describe the techniques of imprinting a seal or a coin as well as of using plaster to make a cast on the face of a living person.

If votive and death masks aim to reproduce the characteristic features of an individual guaranteeing the durability, in a ritual context, of the absent being, anthropological casts are the result of a deritualised practice with scientific pretensions and ideological aims. These artefacts raise questions of an epistemological, ethical and museographic nature because, despite their claim to objectivity, they are in reality the result of a subjective practice that is manifest in both the manufacture of the cast and its colouring. It is important to note that the colour of skin, hair and eyes has been one of the most important anthropological criteria for the classification of human ‘races’ since the end of the eighteenth century. Nélia Dias thus notes that ‘the research [of colours] as an instrument of racial identification and classification is an approach that is part of the process of the production and construction of anthropological knowledge’ (Dias Reference Dias2004, 78).

But the importance of this instrument is inversely proportional to its scientific rigour, and this ambivalence offered fertile ground for fascist propaganda. Skin colour was indeed a major issue in Italy because the debates on race that divided anthropologists concerning the Hamitic origins of Ethiopians were based on the darkness of their epidermis. As Barbara Sorgoni (Reference Sorgoni, Grillo and Pratt2002, 2) explains: ‘Italian anthropologists shared with most anthropologists of the time a concern with the issue of the origin and racial classification of the Hamites. Both the Ethiopians and the Egyptians were believed to belong to the Hamitic race of biblical descent because of their supposed superior civilisation and lighter skin colour, compared to the “rest” of the Africans.’ In the literature of the period, the belief that the Hamites were not ‘real Africans’, she writes: ‘translated into a pride in the fact that the Italians had been able to conquer precisely that part of Africa peopled by those perceived to be of the noblest racial origin with the more advanced customs. At the same time, though, Italian anthropologists underlined the fact that the Hamites had been, from their origins, a coloured race, thus stressing the different racial classification of the Aryan Europeans and the Hamitic Ethiopians’.

Colonial ideology ignored these debates dividing the scientific community in order to simplify its message and increase its impact. From the mid-1930s, Cipriani occupied himself in many writings with developing a theory about the inferiority of the Ethiopian populations. In Un assurdo etnico. L'impero etiopico (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1935), one of his most famous works, he describes Ethiopians as a ‘decadent residue’ (224). The violence of his racist theses is unquestionable because the rhetoric of his demonstration is entirely devoted to justifying the ‘legitimacy and the duty of the Italian empire in Africa’ (321). These theses were made official by the Fascist regime when the Manifesto of the Race was published in 1938, to which Cipriani was a signatory (Cavarocchi Reference Cavarocchi2000). While this manifesto was initially instigated by Mussolini himself, we owe its writing to Guido Landra and to Cipriani an active involvement in its correction (201–202). The eighth chapter of this manifesto focuses on the colonial matter:

It is necessary to make a clear distinction between, on the one hand, the Mediterraneans of Europe (Occidentals), and, on the other hand, the Orientals and Africans. Theories which support the African origin of certain peoples, and which also include the Semitic and Hamitic populations in a common Mediterranean race, must therefore be considered dangerous because they establish utterly inadmissible ideological relations and sympathies.

This statement intervenes in the aforementioned debates that divided anthropologists on the question of the origins of Ethiopians. The Manifesto, however, remains a ‘theoretical pastiche’ (Israel Reference Israel2007, 106) which reflects the uncertainties and difficulties in reconciling the opinions of scientists and anthropologists, as diverse as they are absurd. However, the images and material representations such as facial casts produced and disseminated by Fascist propaganda do not bear the traces of these theoretical inconsistencies, but establish themselves as truths. It is precisely this visual efficiency that makes them indispensable in Cipriani's eyes. He considers facial casts as ‘scientific documents preferable to any metric or photographic data’ (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1938, 8).

Although the scientificity of the casts is now doubtful, at the time these artifacts were considered legitimate scientific material. Cipriani notes that the procedure for their production consists of three stages: ‘modelling, reworking, colouring’ (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1939). Regarding the question of colour, he complains of the Von Luschan scale that ‘in some cases is not able to reproduce the true expression of colour’ (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1930–31, 136). It is therefore probable that when he painted the casts, he added nuances to the colours based on his personal observations noted in the field. In the notebook that recounts his trip to Fezzan in 1932, he specifies, for example, in relation to an Amara soldier, that he ‘could remind one of a Tuareg if he had a beard. He has a skin colour of 23. Different Eritreans have the same “red skin” as the Tuaregs’ (Cipriani Reference Cipriani1932c). This subjective intervention in a supposedly scientific experiment immediately raises the recurring question of objectivity in the construction and dissemination of anthropological knowledge. Cipriani's comment notably reveals the intrinsic non-scientific character of all supposedly objective colour scales relating to the skin, eyes, or hair. Such scales are always merely ideological constructions.

The exhibition of these artefacts in museums played a determining role in the construction and dissemination of racial hierarchies on the scientific as well as cultural level (Bennett, Cameron, Dias Reference Bennett, Cameron and Dias2017; Macdonald Reference Macdonald1998). As the facial casts were, especially during the 1930s, an integral part of museum spaces open to the public – in institutions such as the Florentine museum of anthropology, the Musée de l'homme in Paris, the Natural History Museum of Vienna and the Belgian Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (Couttenier, Reference Couttenier2005) – they acquired the status of material scientific proof of the existence of races. Their hierarchical arrangement in the rooms – following a graduated pattern supposedly reflecting the evolution of mankind – thus served to corroborate theories on the racial classification of humanity. The case study of the Mostra triennale delle terre d'oltremare which opened in Naples in May 1940 is particularly enlightening in this respect (Staderini Reference Staderini and Salvatori2008; Arena Reference Arena2011; Vargaftig Reference Vargaftig2016). The exhibition occupied a space of 100 hectares and included 50 pavilions. While it had to close its doors a month after opening because of the outbreak of the Second World War, it was effectively a small town dedicated to the imperial and racial propaganda of the Fascist regime.

Cipriani undertook a mission to the Ethiopian territories (Galla and Sidama) to prepare for this exhibition. On this occasion he made 59 masks that he wished to exhibit with other samples relating to the populations of Eritrea, Somalia and Libya in the pavilion dedicated to Italian East Africa.Footnote 1 Other Ethiopian casts were exhibited in the ‘race section’, which, under the aegis of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, claimed to demonstrate that ‘the Italian race is defended and rendered more powerful by the regime both in terms of its physical and spiritual integrity as well as in terms of numbers’.Footnote 2 Casts were also on display in the room dedicated to ‘Measures of the regime and racial discipline’ (Provvidenze del regime e disciplina razziale) as ‘evidence’ in support of questions concerning miscegenation (Figures 4 and 5). The anonymous faces of the casts appeared as if in dialogue with the ‘reproduction of the effigy of the Duce, carved in the rock, by the brief artistic awakening of the legionnaires’Footnote 3 in this same room. They also initiated a dialogue with the reproductions of the facies of famous Italians that appeared in the Pavilion of Health, Race and Culture (Padiglione della Sanità, Razza e della Cultura) (Figure 6).

Figure 4 Facial masks displayed during the Mostra triennale delle terre d'Oltremare, 1940, L'Illustrazione italiana no. 22, 2 June 1940: 840–841.

Figure 5 Facial masks displayed during the Mostra triennale delle terre d'Oltremare, 1940, L'Illustrazione italiana no. 22, 2 June 1940: 841.

Figure 6. The Pavilion of Health, Race and Culture, Mostra triennale delle terre d'Oltremare, 1940, Museum of Contemporary Photography (MuFoCo), Milan.

In this context, the display of Cipriani's casts acquires a particular meaning. The circulation of these artefacts was initially limited to internal pedagogical use in museums of anthropology. Their exhibition in the heart of the Mostra triennale delle terre d'oltremare which was addressed to a wider public enabled them to reach their full potential: these objects were here presented as proof of the existence of an African race that was considered inferior. The casts with closed eyes and marked by grimaces resulting from the discomfort of having plaster poured on the skin have a strong aesthetic impact because, just as before a funerary mask, one might suggest, the presence or memory of a deceased being gives rise to a mixture of feelings of fascination as well as distrust, or even repulsion. This contradictory double movement is essential to understand the effectiveness of these artefacts in the propagation of racial theories. They incarnate all the more the locus for racial difference as a result of the contrast with the triumphal portrait of the Duce and the faces of illustrious men erected to represent the physical and moral ideal of Italian masculinity as well as that of Western man in general.

Moreover, the combination of the intense production of casts together with Cipriani's anthropological photographs must be analysed in the context of this anthropologist's strong racist convictions that he sought to popularise through numerous exhibitions, books and articles. His photographs notably played a leading role in the magazine La Difesa della razza (1938–43).

Amalgamations

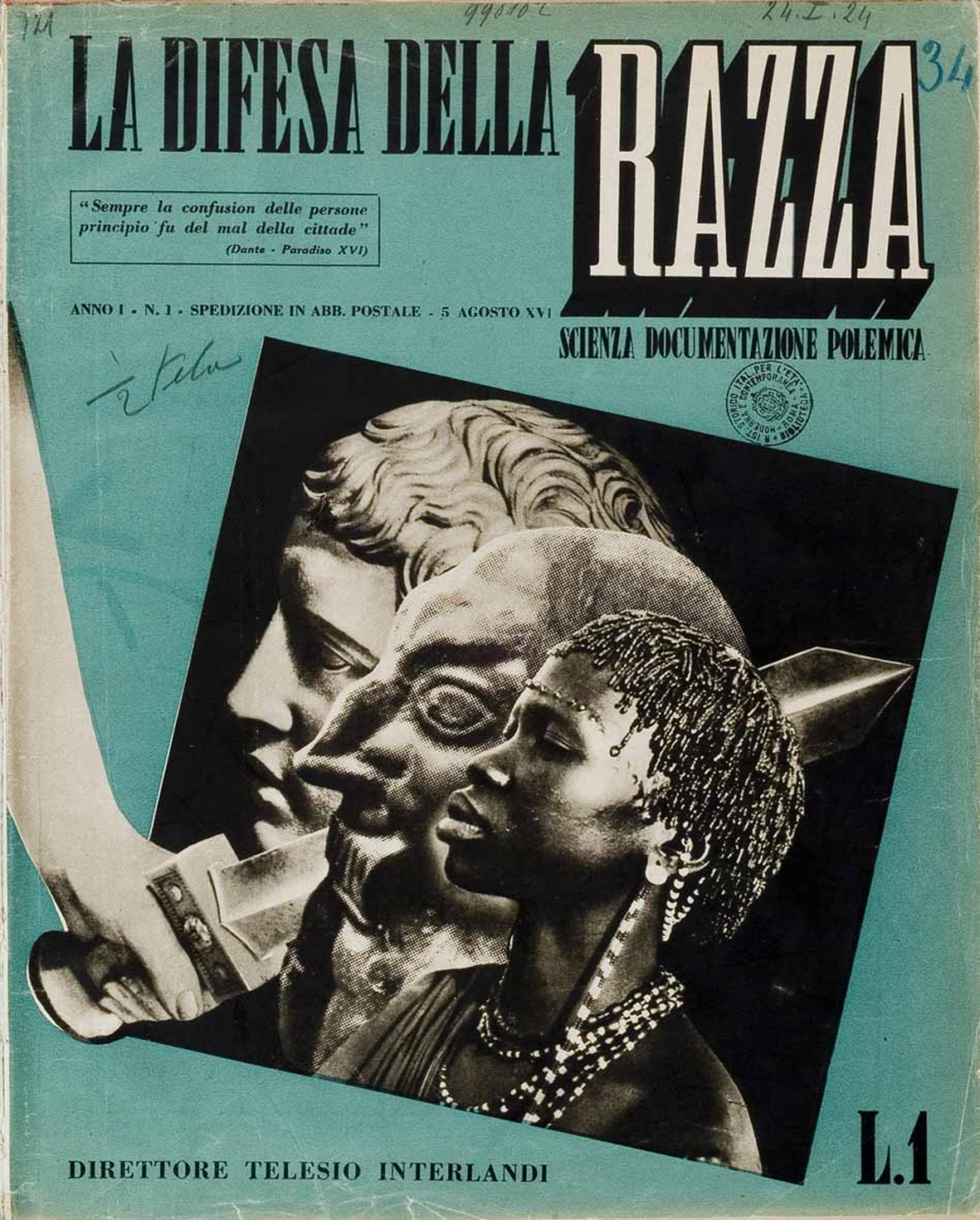

The journal La Difesa della razza is a case study of choice to interrogate the central role of images in the construction and dissemination of racist theories. Published under the aegis of the Ministry of Popular Culture (Minculpop) and the direction of the Sicilian journalist Telesio Interlandi, this bimonthly magazine was one of the most famous periodicals popularising an allegedly scientific doctrine of race in order to justify the colonial and antisemitic policy of the Fascist regime (Nezri-Dufour Reference Nezri-Dufour2017; Cassata Reference Cassata2008). Anthropologists, scientists and philosophers occupied themselves with defending the idea that an Italian race of Aryan origin had been formed several millennia previously, and that this was not, however, a Nordic Aryanism, but a Mediterranean one, superior to the Semitic or African Mediterraneans.

In terms of editing and graphics, the use of images without epistemological considerations – whether it was a matter of anthropological photographs or reproductions of works of art – was put at the service of the ideological violence of the message, similar to the photomontages that adorn the covers. Since the beginning of his career, Interlandi attached great importance to works of art and more generally to images, which he understood as the demonstration of the superiority of Italian culture. He thus wanted to turn the covers of La Difesa della razza into powerful ‘manifestos’ of racism (Cassata Reference Cassata2008, 342). Their aesthetic varies widely; avant-garde compositions are found alongside more traditional and banal illustrations (Luzzatto and de Grazia Reference Luzzatto, de Grazia, Luzzatto and de Grazia2003, 4).

Among the most famous covers is the impactful photomontage published on the three first covers of this journal (1938, Figure 7) juxtaposing the profiles of an ancient sculpture of Polycletus’ Doryphore, of an anthropological photograph of an African woman taken by Lidio Cipriani, and of the image of a caricatural terracotta sculpture of a Semite. These faces are separated by a sword signifying the firm determination of the Fascist regime's racial policy to prevent any form of miscegenation. The collage raises the question of the epistemological status of the images, as it is composed of a photograph reproducing the face of a real woman belonging to the Schilluk ethnic group, the idealised image of an ancient sculpture, and a terracotta caricature dating from the third century CE. This eclectic juxtaposition of faces is part of an iconographic tradition that goes back to the drawings that Peter Camper (1722–89) completed and published in his Dissertation on the Natural Varieties Which Characterize the Human Physiognomy in Diverse Climates (1792). As Anne Lafont (2019) points out, Camper rendered his evolutionary conception of man visible by introducing ancient marble masterpieces into the chain of life. In the photomontage of La Difesa della razza, one finds the same ‘amalgam’ of representations that are not ‘ontologically’ comparable: the first being a photograph of an individual; the second a caricature; and the third an idealised sculpture. Just as in Camper's drawings, ‘the logical sequence provided by the image, despite its persuasive force, is therefore false’ (Lafont Reference Lafont2019, 99).

Figure 7. Cover of La Difesa della razza no. 1, 5 August 1938.

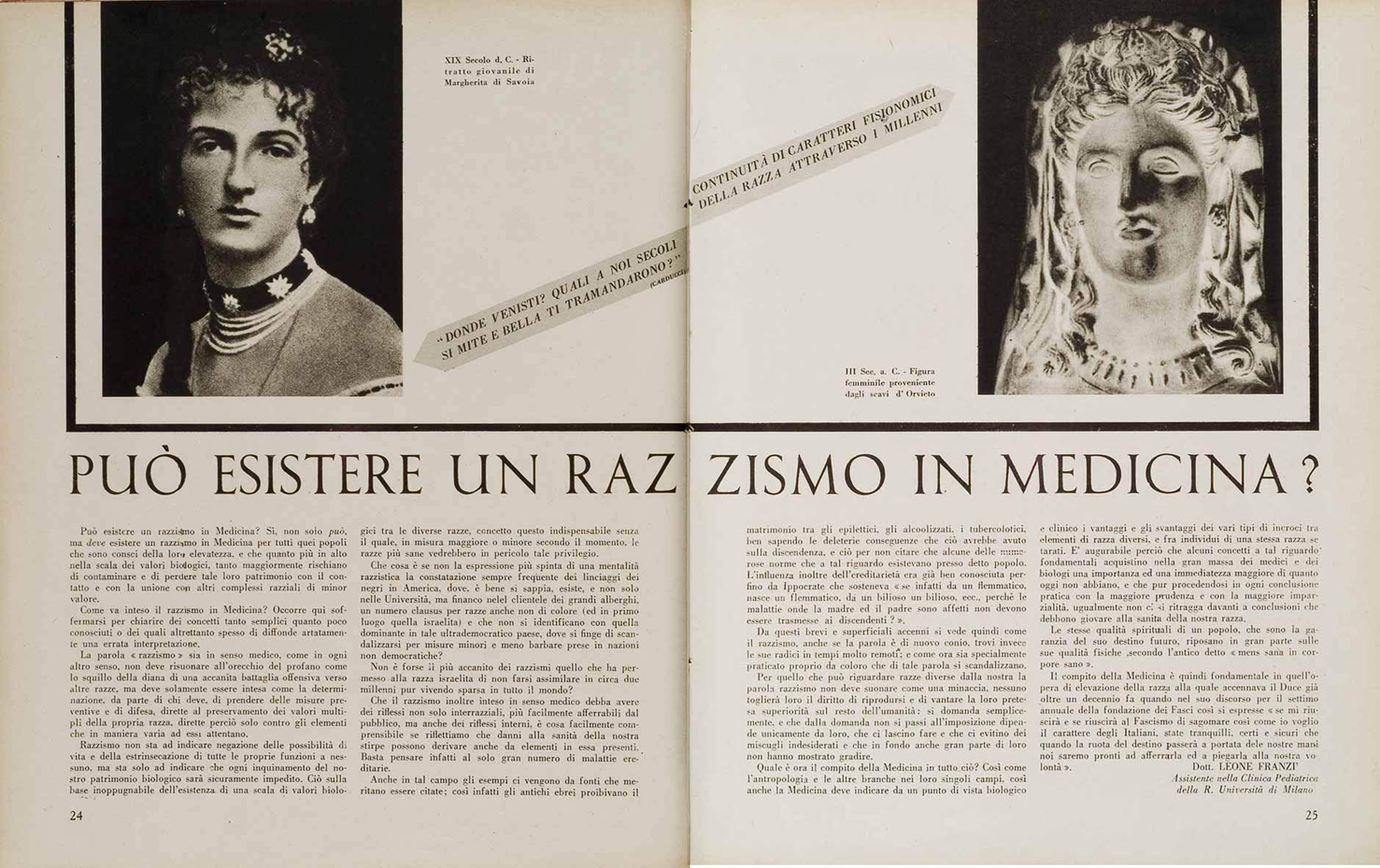

This kind of amalgamation is also omnipresent within the journal. The articles that Cipriani published in it were often illustrated by anthropometric photographs (Figure 8) from his own archive (Iannuzzi, Reference Iannuzzi2021). These images sit alongside other texts by anthropologists and intellectuals which themselves are presented alongside reproductions of paintings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, in particular paintings by Leonardo da Vinci, Piero della Francesca, Raphael, Michelangelo, and Titian, and promote ‘a self-idolatry of the Italian race, celebrating the permanence in time of its somatic and spiritual character’. The St George of Mantegna thus becomes the expression of ‘Italian male pride’;Footnote 4 the Madonna with child and angels of Girolamo dai Libri is identified with ‘Italian purity’; the female figures of Titian and Botticelli are designated as women ‘of Italian race’ (Cassata Reference Cassata2008, 296–297). The combination of a female sculpture of the third century BCE from the archaeological excavations of Orvieto with the portrait of Margaret of SavoyFootnote 5 claims to illustrate the Continuità di caratteri fisionomici della razza attraverso i millenni (Continuity of the physiognomic characters of the race through the millennia) (Figure 9). References to Greco-Roman statuary are as frequent as they are significant. Julius Evola (Reference Evola1940) also used reproductions of Greek statues to illustrate his text ‘Supremi valori della razza ariana’ (‘Supreme Values of the Aryan Race’): the sculpted head of Jupiter, statues of Apollo, that of the Hermes of Praxiteles and that of Athena are thus presented to illustrate a solar and Olympian ‘Aryan race’ (Figures 10–12).

Figure 8. Illustrations in the Lidio Cipriani article, ‘Razzismo’, La Difesa della razza no. 1, 5 August 1938: 12–13.

Figure 9. Illustrations in the Leone Franzì article, ‘Può esistere un razzismo in medicina ?’, La Difesa della razza no. 1, 5 August 1938: 24–25.

Figure 10 Illustrations in the Julius Evola article, ‘Supremi valori della razza ariana’, La Difesa della razza, no. 7, 5 February 1940: 15–16.

Figure 11 Illustrations in the Julius Evola article, ‘Supremi valori della razza ariana’, La Difesa della razza, no. 7, 5 February 1940: 17–18.

Figure 12 Illustrations in the Julius Evola article, ‘Supremi valori della razza ariana’, La Difesa della razza, no. 7, 5 February 1940: 19.

Other covers deal more directly with the issue of miscegenation. One such is that of March 1940, which presents a photomontage of a cast belonging to Cipriani's collection and the image of a headless bust of a female fashion model (Figure 13). The meaning of this surrealist assemblage remains enigmatic. The mannequin – as a metaphysical and abstract symbol of man – is a leitmotif in the painting of Giorgio De Chirico. As the art of De Chirico had previously been defined by Interlandi as a ‘barbaric aesthetic’ and ‘a cancer that must be cut out’ (Interlandi Reference Interlandi1938), one may assume that this composition draws an awkward comparison between the dehumanisation of the human figure that would result from the avant-garde and the degeneration that miscegenation would cause. It is worth noting that Interlandi's theses favouring the kind of art that ought to incarnate the purity of the Italian race and the virulent attacks on the physical deformations of the art of the avant-garde employ the same arguments that are also to be found in the Nazi campaign against ‘degenerate’ art (Piccioni Reference Piccioni2021, 307–326).

Figure 13. Cover of La Difesa della razza no. 9, 5 March 1940.

This analogy is reiterated in the drawing by Bepi (Giuseppe Fabiano) published on the cover of the December 1940 issue: the Greek profile of a white man merging into the profile of a black woman (Reference Campassi and SegaFigure 14). Where these stereotyped silhouettes meet, one sees a photograph of a skull, signalling the danger of death brought about by such a coupling.

Figure 14. Cover of La Difesa della razza no. 3, 5 December 1941.

Mobile essentialisms and women's faces: conclusions

Historian Ann Laura Stoler has argued that ‘imperial authority and racial distinctions were fundamentally structured in gendered terms’ (Stoler Reference Stoler2002, 42). The Italian case confirms this hypothesis. The stereotypical images of African woman that were formed from the nineteenth century onwards most often present her as an erotic Venus, implying an analogy between the woman who offers herself and a territory to be taken, between carnal possession and colonial conquest (Surdich Reference Surdich1979; Campassi and Sega Reference Campassi and Sega1983). Barbara Sorgoni (Reference Sorgoni1998, 61) points out, however, that this reading can be reductive, as it excludes ethnographic images intended for documentary purposes, as well as photographic portraits deriving from physical anthropology, which coldly review the characteristic features of the face to inspire rejection rather than desire and to demonstrate the supposed inferiority of Africans. She further notes that this analysis ‘cannot account for the changes that occur at the political and ideological level over time – with the fascist regime and particularly with the foundation of the empire – which are also reflected on the iconographic level.’

As mentioned in the introduction to this essay, what distinguishes Italian colonialism from that of other European countries is notably the enactment of racial legislation drawn up in the colonies and which initially consists in the prohibition of mixed marriages between Italians and Africans. This moment of the radicalisation of racial politics coincides with changes in the popular imagery of women. Anthropological images thus play a leading role in an essentialisation of the female body that is to be seen as reification rather than sexualisation, and whose impact is not confined to the academic discipline of anthropology, but equally concerns mass culture.

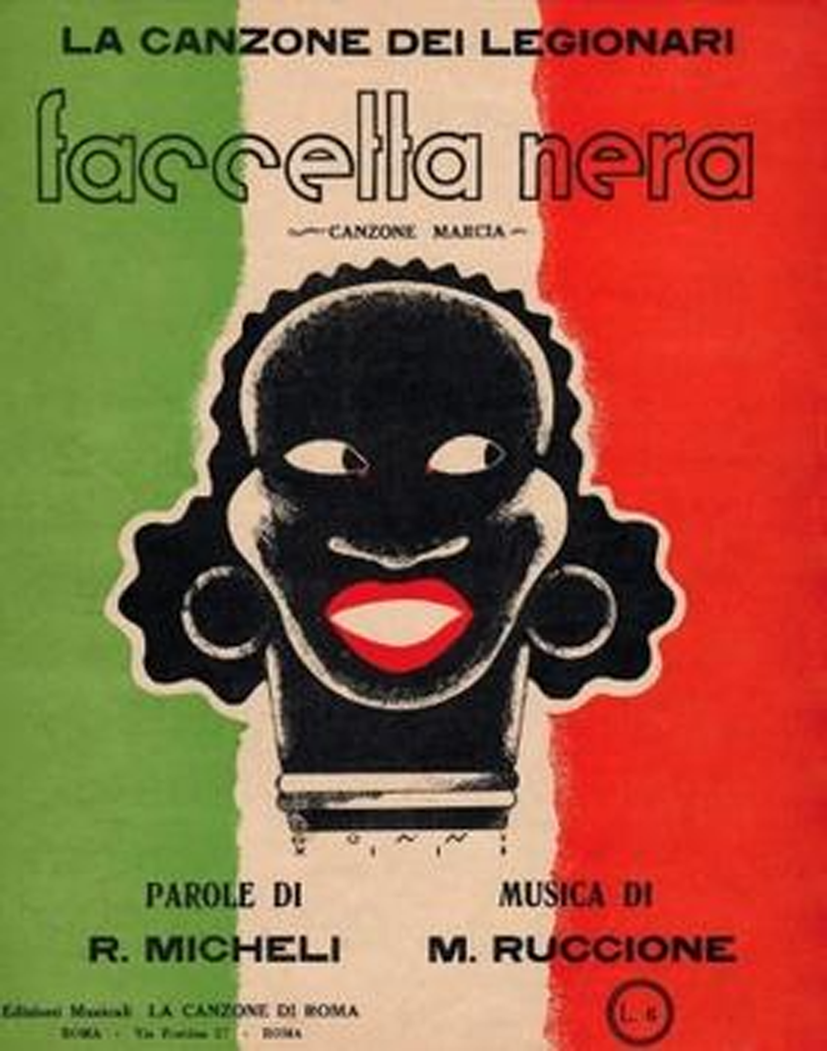

The visual imagery related to the famous song Faccetta nera (Little Black Face, text by Renato Micheli, music by Mario Ruccione, 1935) is the most popular expression of such reification of female bodies, and, more specifically, African female faces (Vaccarelli Reference Vaccarelli, Cagnolati, Pinto and Ulivieri2013; Righettoni Reference Righettoni2018, 74–76). Faccetta Nera – both as a song and as a source of visual imagery (Figure 15) – shows the continuity of the stereotype of the African woman as an object of desire as well as a profound change in the value of this image linked to the hardening of racial discourse in the aftermath of the invasion of Ethiopia. As demonstrated in recent works, ‘on the one hand, Faccetta Nera represented a call to enrolment in the colonial army; on the other hand, it caused embarrassment and concern due to the new attitudes of the regime towards relationships between Italian colonisers and their colonies’ (Vaccarelli Reference Vaccarelli2017). Indeed, this song sparked debates around the legitimacy of its popularity at a time when racial laws prohibited any relationship between Italians and African women (Righettoni Reference Righettoni2018, 74–80; Volpi Reference Volpi2018). While some saw it only as a lightly evocative and joyful piece, others objected that it could arouse some form of desire. Thus, in an article eloquently entitled ‘Wives, like cattle, must belong to your country of origin’ (Mogli e buoi dei paesi tuoi), journalist Paolo Monelli indulged in a shameful comparison of African women with animals, in order to discourage any relationship with them (Monelli Reference Monelli1936). The newspaper linked to the Tuscan group Strapaese, and which in the mid-1930s was a critical voice challenging the radicalisation of the Mussolini regime, published a comment in the same vein: ‘Very just outcry about Faccetta Nera and against its pathos and, alas, its very numerous variations in postcards and photographs, nudes, large black breasts and so on, which have been circulating recently without impediment’.Footnote 6 Despite these controversies, the image of the face of an African woman remained very popular, as evidenced in the copies of advertising stored in the state archives (Righettoni Reference Righettoni2018, 76). This kind of representation repeatedly served as an advertising icon for cans of tomatoes (Figure 16) or olive oil.

Figure 15. Record cover for the song ‘Faccetta nera’, 1935.

Figure 16. Advertisement for ‘Faccetta nera’ tomato sauce, c1936.

How is such continuity to be explained? Following Foucault's ideas, Stoler emphasises ‘the polyvalent mobility’ of racist essentialism (Stoler Reference Stoler2016, 245). The coexistence within the popular imagination of images of woman both as object of desire and of contempt in the years of the ideological consolidation of the Fascist regime is a clear illustration of this protean character of the notion of race. It is this plasticity that guarantees the tenacity of racism.

Analysis of the Italian case notably enables us to observe that images of faces play the role of a matrix in the definition of concentric circles of alterities whose contours are however fluid. Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari (Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987, 178) define racism as operating ‘by the determination of degrees of deviance in relation to the White-Man face, which endeavours to integrate nonconforming traits into increasingly eccentric and backward waves, sometimes tolerating them at given places under given conditions, in a given ghetto, sometimes erasing them from the wall, which never abides alterity (it's a Jew, it's an Arab, it's a Negro, it's a lunatic …)’ (Deleuze and Guattari Reference Deleuze and Guattari1987).

The representations of black faces, whether deriving from the field of anthropology or from popular culture, shape a persistent racial imaginary. This study is intended to demonstrate that only an interdisciplinary approach allows one to reconstruct the multiple racial epistemologies and the entanglements between anthropological knowledge and popular ‘common knowledge’. It thus aims to encourage collective work that would make it possible to assemble and to study a vast corpus of images in order to develop avenues of research to understand how the dissemination of racist images plays an active role in the construction of political discourse. The facial casts and the anthropological photographs, the magazine illustrations, the advertising images in effect all give consistency to the notion of race, and embody simultaneously its protean nature made up of narratives, metaphors, fantasies and prejudices constructed and accumulated over time.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Carmen Belmonte and Laura Moure Cecchini for useful discussion and for their patience and support.

Competing interests

the author declares none.

Lucia Piccioni is currently Marie Skłodowska-Curie Fellow at the European University Institute (Florence). Her research investigates the relation between art and politics, with a special focus on fascist art and the role of visual and material culture in the construction of Italian identity from the nineteenth to the twentieth century. She received her PhD in Art History from the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS), Paris and the Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa, with a dissertation on fascist Italian painting (awarded Best Dissertation by EHESS). She has had fellowships at a number of international institutions, including the Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte, Paris, the Center for Italian Modern Art, New York, the French Academy in Rome–Villa Medici, and the Musée du quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Paris. In addition to papers in international journals, she is author of Art et fascisme. Peindre l'italianité, 1922–1943, Les presses du réel, 2021.