Introduction

“In theory,… federal judges form a pyramid that supports the will of [Supreme Court] Justices. In reality, federal judicial power is widely diffused among lower court judges who are insulated by deep traditions of independence” (Reference Howard and WoodfordHoward 1981:3). As this quote describes, the federal judicial hierarchy is designed to enable the Supreme Court, sitting at the system's apex, to impose its collective will on lower federal judges. Yet the Court's control is far from absolute: the decentralized structure of the federal judicial system, in combination with the Court's limited institutional capacity, provide lower court judges with considerable discretion to fashion case outcomes in accordance with their own legal and policy preferences. These cross-pressures in the federal court system have led scholars to examine the extent to which the High Court successfully influences the decisional outputs of the courts below (Reference JohnsonJohnson 1979; Reference GruhlGruhl 1980; Reference SongerSonger 1987; Reference Songer, Segal and CameronSonger, Segal, & Cameron 1994; Reference Cameron, Segal and SongerCameron, Segal, & Songer 2000; Reference BaumBaum 1994).

Appellate supervision over lower courts is not exercised solely by the U.S. Supreme Court. In the lower tiers of the hierarchy, circuit courts are expected to monitor the decisional outputs of the federal district courts (Reference BaumBaum 1980). Of course, the most significant supervisory tool available to the circuit court is the power to reverse or affirm the lower court. Although the power to reverse is exercised relatively infrequently by the circuit courts, it nevertheless serves as a compelling mechanism to shape lower court decision making and to signal the circuit's preferences concerning legal policy. Affirmances also serve to signal the circuit court's preferences and shape lower court decisional outcomes by confirming the approach adopted by the trial court. In this article, therefore, we ask how appellate courts use this significant power of review to control decision making in the lower courts. In particular, we seek to identify the critical determinants underlying appeals court judges’ choices to alter the status quo created by the lower court's ruling. As part of that effort, we recognize that this decision may be influenced by an institutional environment in which resources are scarce and caseloads are high. Drawing from a theoretical perspective that recognizes the interplay between attitudes and institutional structures in models of judicial decision making, we identify and evaluate the determinants of circuit court decisions to affirm or reverse the judgment of the district court in civil rights and liberties cases over a 29-year period. Our findings reveal that the decision to reverse in particular is shaped by factors specific to the individual case, by judges' policy preferences, as well as by broader institutional dynamics generated by the judicial hierarchy as a whole.

Circuit and District Courts Within an Institutional Hierarchy

Supervision of the trial courts by the circuit courts is a routine activity that contrasts sharply with the type of appellate supervision exercised by the Supreme Court through certiorari review. Since litigants generally enjoy a right to appeal, the circuit courts must examine the outputs of trial courts on a regular basis. According to one scholar, “trial courts make mistakes, and appellate courts, because of their greater expertise, lesser time pressures, collegial decision making, or some other reason, correct those mistakes” (Reference DrahozalDrahozal 1998). In addition to error correction, traditional scholarship also recognizes the important policy making associated with appellate review, mainly stemming from cases requiring statutory and constitutional interpretation. As Judge Reference NewmanJon O. Newman has observed, “Reasonable judges will inevitably come out differently on close questions of law. The hierarchical structure of a judicial system requires that even a well-reasoned view of a trial judge will be displaced by the well-reasoned view of a panel of appellate judges” (1992:630; see also Reference Landes and PosnerLandes & Posner 1979:252). Thus, the institutional role of the appellate courts requires that circuit court judges actively monitor trial court decisions to ensure that errors are corrected. This institutional role is not limited to error correction. Appellate oversight in the lower tiers of the federal judicial hierarchy also provides a process through which circuit judges are expected to promote legal rules that will guide decision making in subsequent cases.

Decision making in the lower tiers of the federal judiciary is thus subject to some control by judges at superior levels. Circuit judges monitor and supervise decisional outputs below. In doing so, circuit judges seek to ensure that the trial courts' decisions are consistent with their policy preferences, and (presumably) that the Supreme Court's dictates are being followed. Attitudinal theories of judicial behavior would therefore suggest that ideological differences and similarities between the judges within the hierarchy largely explain the dynamics of appellate review. Indeed, existing studies clearly demonstrate that circuit judges make decisions to further their policy preferences (Reference Songer and HaireSonger & Haire 1992; Reference Howard and WoodfordHoward 1981), while other studies suggest that trial judges derive utility from the pursuit of a number of goals, including ideological utility from deciding cases in accordance with their policy preferences (Reference Rowland and CarpRowland & Carp 1996; Reference Richardson and VinesRichardson & Vines 1970). Thus, policy goals pursued by district judges have the potential to conflict with the objectives and preferences of their superiors in the circuit court.

Judges do not act on their preferences in a vacuum, however. Although they exercise mandatory jurisdiction over appeals from the district courts and thus review all appeals brought before them, circuit judges’ supervisory power is subject to some important institutional constraints. In particular, the scope of appellate review is limited and does not include the same exposure to case facts. Circuit judges therefore conduct appellate review with less information about the case. Trial judges operate under some informational disadvantages as well. Although they may desire to follow circuit preferences faithfully, information about those preferences may be difficult to discern. Circuit judges sit in panels of three, but the individual panel's preferences may differ from those of the circuit as a whole. In addition, where circuit precedent is marred by numerous dissenting opinions, it complicates district judges’ ability to predict the proper outcome. Finally, the trial judge must also defer to Supreme Court precedent. Yet where the circuit and Supreme Court are in ideological conflict, the trial judge may find it difficult to identify the applicable legal rule.

In several respects, these institutional dynamics associated with appellate review in the federal judicial hierarchy are captured by principal-agent theory. According to principal-agent theory, the agent is expected to choose actions that support the outcomes desired by the principal (Reference MoeMoe 1984). When the goals of principal and agent are consistent, the principal-agent arrangement is likely to operate smoothly. However, the goals of principals and agents do not always coincide. Agents may be motivated by other interests, including their own self-interest, thus creating goal conflict between agent and principal (Reference Waterman and MeierWaterman & Meier 1998). In such circumstances, the agent may shirk or even sabotage the principal's objectives (Reference Brehm and GatesBrehm & Gates 1997). Information asymmetries often contribute to the likelihood of shirking, particularly when the principal's monitoring costs are high (Reference MoeMoe 1984). Consequently, principals may rely on screening devices or signals, including “fire alarms” raised by external parties, to compensate for the informational deficit (Reference MoeMoe 1984; Reference McCubbins and SchwartzMcCubbins & Schwartz 1984). Furthermore, the principal-agent relationship is sometimes complicated by the existence of multiple principals and agents (Reference MoeMoe 1984; Reference Benesh and MartinekBenesh & Martinek 2001).

Of course, principal-agent theory as initially constructed by economists does not apply as strictly within the federal judiciary. District and circuit court judges enjoy life tenure and thus are not subject to the employment-based sanctions that may be imposed on an employee or contractor who serves at the principal's will. Lower federal judges may remain secure in their prestigious positions regardless of the consequences of their legal judgments, as long as those judgments are rendered within reason. Moreover, reversal in individual cases does not constitute as significant a sanction as may be imposed within private economic interactions, where the loss of a job or contract is possible when the agent displeases the principal. Reversal is a particularly unimpressive sanction in the context of circuit-Supreme Court interactions, where the likelihood of reversal by the Supreme Court in any individual case is so small as to render it essentially meaningless as a sanction (Reference CohenCohen 2002:42–45).

At the district court, however, affirmance or reversal by the circuit court may have more impact, and thus more clearly support application of principal-agent theory within the lower tiers of the judiciary. First, unlike at the circuit court, where the likelihood of elevation to the Supreme Court is highly improbable, elevation from the district court to the circuit is far more likely. Like all professionals, judges prefer to be held in high esteem by their colleagues and may desire promotion and elevation to a higher court (Reference CohenCohen 1991, Reference Cohen1992; but see Reference Higgins and RubinHiggins & Rubin 1980). Frequent reversals could impede a judge's ability to achieve these professional goals. Indeed, senatorial hearings often focus on the judge's “track record” in terms of affirmances and reversals, and thus judges interested in elevation may seek to conform their behavior to circuit court preferences (see Reference CohenCohen 1991; cf. Reference Ramseyer and RasmusenRamseyer & Rasmussen 2001). Moreover, strong norms of vertical stare decisis operate to constrain judges' decisions. Many judges want to “get it right” simply because they have internalized norms of stare decisis through their professional training and because judicial decisions must be rationalized on the basis of precedent (cf. Reference Knight and EpsteinKnight & Epstein 1996). Finally, a reversed or vacated decision often results in additional work for the district court if the circuit panel remands for further proceedings. District judges who value their leisure time will therefore wish to avoid the increased workload associated with a remand. For these reasons associated with professional advancement, norms, and workload, a circuit panel's decision to affirm or reverse carries with it some “sanctioning” authority. Relations between the circuit panel and district judge below may therefore be productively characterized as a principal-agent relationship, albeit with a reduced sanctioning capacity on the part of the principal.

As outlined above, this theoretical perspective suggests that given the circuit's ability to supervise and correct district court judgments, the influence of vertical stare decisis, and the modest sanction associated with reversal (and remand), district court judges will often conform their decisions to circuit court preferences. The circuit court is not the only principal to whom the district judge must respond, however. The Supreme Court also issues directives in the form of opinions that it intends the district court to follow. Although the principal-agent relationship most often depicted in the scholarly literature tends to be conceptualized as a simple (single) dyad, multiple-principal arrangements such as this are not unusual in organizations (Reference BrentBrent 1999; Reference MoeMoe 1984). Subordinates may follow directives from more than one superior, with organizational leaders attempting to impose consistency through a cooperative arrangement. However, principals also may compete for influence over the agent, who may then be subject to cross-pressures. In these circumstances, the agent may be “attracted to strategies that play principals off against one another” (Reference Waterman and MeierWaterman & Meier 1998:180). In the judicial context, the district court judge may be sensitive to the relations between the circuit and its immediate superior, the Supreme Court. District judges may find themselves “trying to please two masters” when the preferences of their circuit superiors are at odds with those of the Supreme Court. And while the Supreme Court generally does not have direct sanctioning authority over the district court, the Supreme Court's judgments influence those of the district court's immediate superior in important ways.

In addition, principal-agent models suggest that agents often enjoy an informational advantage over their principals. Given their role in the implementation process, agents typically have access to more information concerning factual context and alternative implementing strategies. This theoretical principle is clearly applicable to the appeals process, where trial judges develop a more thorough understanding of case facts than do circuit judges. As described by Circuit Judge Coffin, “Over time I have seen enough transcripts, trial records and administrative agency case files to have a healthy respect for the effort and competence that have been invested at the first level of adjudication” (1994:265). Not surprisingly, standards of review employed by appeals courts accord a high level of deference to trial courts in their fact-finding role. These standards promote efficiency in the appeals process by preserving the circuit's institutional resources. One of the basic principles of appellate review is that the appeals court should not disturb the findings of the trial court unless legal error in the proceedings will result in substantial prejudice to the interests of a party (ABA 1994). Indeed, a trial judge's findings of fact will be reversed only if they are clearly erroneous, as trial judges are present to consider the credibility and demeanor of witnesses and thus have first-hand knowledge of the litigants' factual assertions.

Viewed in light of agency theory, circuit courts' deference to factual findings made below provides a district judge with opportunities to shirk the circuit's policy objectives, since circuit court panels may be reluctant to expend the institutional resources necessary to eliminate the informational deficit on factual matters related to an appeal (Reference MoeMoe 1984). On the other hand, this informational asymmetry is offset, at least in part, by the important policing activities of individual litigants, who can sound the fire alarm if a district judge chooses to thwart the circuit's policy mandates (Reference ShavellShavell 1995). The appeals process itself therefore provides the circuit court with a monitoring mechanism that may ultimately lead to enforcement through the decision to reverse. To monitor a trial court, the circuit court panel will review litigants' appellate briefs, the lower court decision, and relevant portions of the record below. In this process, circuit judges enjoy the benefits of lesser time pressures, collegial decision making, and a broader perspective on the interpretation and applicability of legal doctrine.

These observations would indicate that relations between the circuit and district court levels will be shaped by the degree of goal conflict between judges on the two courts, as well as the extent to which the circuit court is able to overcome its information deficit. To assess the extent to which their agents are pursuing their own goals rather than those of their principals at the circuit courts, circuit judges must monitor and supervise the trial court's activities. Reversal serves as a useful tool in this monitoring process, as reversal not only corrects an individual deviation, but also signals the lower courts concerning circuit-level preferences for future cases. Circuit judges are well aware of their supervisory authority and, specifically, the forward-looking effects of reversal: “one learns from long and frustrating experience that one reversal is worth a hundred lectures” (Reference CoffinCoffin 1994:163). Thus, reversals reflect not only the circumstances involved in the individual case, but also the institutional dynamics between the circuit and lower courts. Indeed, we expect that factors related both to the individual case and to the broader institutional context will influence the appeals court decision to reverse or affirm.

As a result, this theoretical perspective differs substantially from a simple attitudinal approach because it highlights the role of institutional factors inherent in the hierarchical structure as influencing the relations between district and circuit court. Current studies of judicial behavior widely recognize that judges' decisions are structured not only by their policy preferences, but also by their institutional context (Reference Hall, Brace, Clayton and GillmanHall & Brace 1999; Mahlzmann, Spriggs, & Wahlbeck 2001). Although judges may be primarily motivated by their policy preferences, their pursuit of those preferences is often constrained by institutional rules and norms that require judges to compromise with other judges (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein & Knight 1998). For circuit judges reviewing decisions by district court judges, these institutional constraints include the mandates of their own principal at the Supreme Court, as well as information asymmetries and uncertainty inherent in the nature of appellate review of law rather than facts. We argue, therefore, that circuit judges respond to institutional pressures and dynamics as well as their policy preferences when rendering decisions. Similarly, district court judges face their own institutional constraints when they decide cases. District court judges, like circuit judges, are motivated by their policy preferences. But they also are constrained by appellate review. Even for the district judge who wishes to implement circuit policy faithfully, uncertainty and information deficits concerning circuit-level preferences complicate the task.

We outline in more detail below these expectations and draw on the insights of agency theory to identify potential influences associated with goal conflict and information asymmetry between circuit courts and trial courts. We also incorporate the effect of the Supreme Court on the circuits' interactions with the federal district courts. Our hypotheses are formulated so as to focus on factors affecting the decision of an individual circuit panel to affirm or reverse the district court's decision below.

Research Hypotheses

Goal Conflict

As previously noted, a key feature of the agency problem is goal conflict between principal and agent (Reference Waterman and MeierWaterman & Meier 1998). When the goals and intentions between principal and agent differ, the principal must be more vigilant in supervising and enforcing its will. As applied to interactions between judges on the circuit and district courts, the outcome of appellate review may be expected to vary with the level of agreement between the preferences of the reviewing panel and the policy position taken by the trial judge. If the policy goals of the trial court and the appeals court panel are not shared, the outcome of monitoring is more likely to result in reversal.

H1: A circuit panel is more likely to reverse when the policy outcome of the district court decision is inconsistent with the dominant preferences of the panel.

The policy preferences of the district court judge may also differ from those of the majority of judges on the reviewing circuit, reflecting broader institutional dynamics. As the distance between the ideology of the district court judge and the circuit's ideological center increases, one would expect the trial court's decisions to conflict with the views of the circuit majority more frequently. In these circumstances, litigants will be more likely to appeal, expecting to draw a panel that is sympathetic to their position. Although this expectation may flow from the litigant's perception of the policy preferences of the circuit as a whole, the appellant may be more likely to prevail even if the reviewing panel judges' preferences suggest otherwise. Due to the potential for rehearing en banc, individual panels in the circuit are sensitive to the policy predisposition of the majority (Reference Van WinkleVan Winkle 1996). For the same reasons, we expect a district court judge to be affirmed more often when his or her preferences are closer to the circuit's ideological center. Moreover, for these judges, recent circuit precedent will generally be consistent with their policy views, further reinforcing the likelihood that they will faithfully implement the circuit's goals.Footnote 1

H2: A circuit panel is more likely to reverse as the distance between the district judge's policy preferences and the ideological center of the circuit increases.

On the other hand, if agent and principal share the same policy goals, the need for policing and monitoring should be reduced (Reference Waterman and MeierWaterman & Meier 1998). One would expect, for example, that goals are more likely to be shared when one of the panel members is a district court judge sitting by designation. In these instances, we expect that district judges sitting by designation will be more likely to support rulings by a fellow trial judge and may even persuade the other panel members to do likewise. In their study of district court judges sitting by designation on the courts of appeals, Reference Green and AtkinsGreen and Atkins (1978) found that district court judges shied away from writing reversing opinions. This finding suggested to Green and Atkins that “when district court judges are appointed to appellate panels they approach their task with divided loyalty. A desire to support their colleagues on the trial bench apparently leads them to avoid reversing behavior” (1978:368). The authors further found that panels with district court judges sitting by designation also reversed the lower court somewhat less frequently. As a result, we hypothesize that:

H3: A circuit panel is less likely to reverse when the panel includes a district court judge sitting by designation.

In addition, the likelihood of reversal may vary by circuit as formal circuit rules and informal circuit norms create varying levels of deference to trial court judges. Quite simply, in some circuits appeals court judges may be more tolerant of trial court decisions that deviate from their preferences. Moreover, the circuits’ docket composition may differ sufficiently such that error is more likely in some circuits. For example, in districts and circuits where more cases go to trial, where more complex legal questions are raised, and where a more litigious culture exists, one might expect the likelihood of reversal to be affected (Reference Howard and WoodfordHoward 1981). Hence, to assess the influence of such circuit-level norms, we offer the following hypothesis:

H4: A circuit panel is more likely to reverse in circuits that have demonstrated a propensity to reverse in prior cases.

Information Asymmetry, Signals, and Uncertainty

We noted earlier that circuit courts generally defer to the district court's findings of fact given the district judge's first-hand knowledge of testimonial evidence. Circuit-level norms of deference toward the district court's factual findings thus clearly reflect the informational asymmetry between the two courts, as well as the need for the efficient disposition of appeals. Even so, circuit judges must monitor the district court's outputs to ensure consistency with their own preferences. To overcome informational asymmetries in the monitoring process, circuit judges may rely on signals to assist in their evaluation of the trial court's ruling. Indeed, the use of signals and cues in the judicial decision-making process has been noted elsewhere. For example, in the context of the decision to grant the writ of certiorari, the Supreme Court relies on signals from the lower courts and from other governmental actors to identify cert-worthy cases (Reference PerryPerry 1991). Similarly, Reference Cameron, Segal and SongerCameron, Segal, and Songer (2000) found that, in choosing cases to review, the Court appears to rely on ideological cues and signals by demonstrating a propensity to “give the benefit of the doubt” to conservative panels rendering liberal decisions, and vice versa. In the same way, the circuit court panel may rely on the trial judge's ideological predilections as a useful signal in the process of appellate review. When a district judge renders a decision that is at odds with his or her own policy preferences, the circuit court panel may use that information to conclude that the decision below is more likely to be acceptable to the panel. In light of this potential dynamic, we suggest that:

H5: A circuit panel is less likely to reverse when the outcome below is inconsistent with the district judge's policy preferences.

In their efforts to overcome informational disadvantages in the review process, circuit court judges may also rely on the personal characteristics of the district court judge as a signal or cue in deciding whether to reverse.Footnote 2 In particular, the circuit court may assume that the decisions of newly appointed district court judges require closer scrutiny. Moreover, this assumption may be justified; new district court judges may simply make more errors as they become assimilated to their new jobs. In connection with these suppositions, we offer the following hypothesis:

H6: A circuit panel is more likely to reverse the decision of a district court judge who is newly appointed to the federal bench.

Trial courts also face informational deficits that potentially affect the need for and the nature of appellate supervision.Footnote 3 In particular, appellate oversight may vary with subordinates’ understanding of upper court preferences (Reference Canon and JohnsonCanon & Johnson 1999; but see Reference JohnsonJohnson 1979). For example, if the clarity of circuit law is confounded by conflicting panel decisions, trial judges will not be certain which rule should be followed and will have difficulty discerning the circuit's policy preferences. Inconsistent circuit precedent may confuse trial court judges, including even those who wish to adhere faithfully to circuit policy. The clarity of circuit law is particularly undermined by dissenting opinions (Reference Wasby, Sheldon and LambWasby 1986), since dissenters often argue that the majority opinion improperly interprets circuit law. In circuits where dissensus is high, district court judges face mixed (and often misleading) signals from their superiors, increasing the likelihood of reversible error (Reference Rowland and CarpRowland & Carp 1996). In contrast, in those circuits where consensual norms reduce the expression of conflict, one would expect to find greater certainty in law (see Reference HellmanHellman 1999). Trial court judges, guided by clear precedent, also will be able to estimate more clearly the likely preferences of a reviewing panel.Footnote 4

A measure of dissensus offers an observable circuit-level indicator that we suspect to correlate with the ability of district court judges to assess the preferences and precedent of the circuit. A similar circuit-level indicator focuses on the utilization of en bancs. En banc decisions offer district court judges an important source of information on circuit legal policy, since the preferences of the entire circuit bench are clearly exposed. The utilization of en bancs is not uniform across the circuits or over time, however (Reference BanksBanks 1999). Some circuits grant en banc review very infrequently, while others use the process regularly (Reference NewmanNewman 1994; Reference BanksBanks 1999). Thus, in circuits that use the process more regularly, trial judge uncertainty as to circuit preferences may be reduced.Footnote 5 Based on this reasoning, we propose that:

H7: As the dissent rate of a circuit increases, subsequent circuit panels are more likely to reverse district court decisions.

H8: As the use of en bancs in a circuit increases, subsequent circuit panels are less likely to reverse district court decisions.

The Principal's Principal: The Supreme Court

We suggested above that district court judges may be sensitive to the relationship between its two principals in the circuit and Supreme Court. When the Supreme Court increases its monitoring of the circuit, thus revealing the Court's potential displeasure with the circuit's decision making, the district court may be more likely to engage in a strategy that results in noncompliance or defiance of the circuit's policy goals. On the other hand, the existence of a cooperative arrangement between the Supreme Court and circuit court would increase the likelihood of district court decisions that conform with that circuit's policy goals.

H9: As the level of Supreme Court scrutiny increases, subsequent circuit panels are more likely to reverse district court decisions.

Although there are multiple courts that exercise appellate review in the federal judicial system, the Supreme Court stands at the apex of the judicial bureaucracy. As the circuit court's superior, the High Court has the power to review, and reverse, decisions of the appeals courts (e.g., Reference George and SolimineGeorge & Solimine 2001). Prior research suggests the circuit courts are generally “faithful agents” of the Supreme Court (Reference Songer, Segal and CameronSonger, Segal, & Cameron 1994). Therefore, one would expect that the circuit's monitoring behavior will be influenced by the possibility of subsequent review by the High Court. When the district court renders decisions that are consistent with the Supreme Court's preferences, the circuit court, as agent to the Supreme Court, will have less reason to reverse. Hence, we test the hypothesis that:

H10: A circuit panel is less likely to reverse the district court decision when the outcome is consistent with the dominant preferences of the Supreme Court.

The hypotheses set forth above suggest that the district court decision is more likely to stand when it conforms to Supreme Court expectations, but the Supreme Court's oversight role is often assessed in terms of policy implementation as well. Scholars have identified several factors that are likely to affect lower court interpretation of Supreme Court precedent, including opinion clarity, communication of information about the case, and perceptions of Court support for the majority opinion (Reference Canon and JohnsonCanon & Johnson 1999; Reference JohnsonJohnson 1979; Reference Pacelle and LarryPacelle & Baum 1992). When cues from the High Court are ambiguous, one would expect more frequent monitoring activity by the circuits as litigants and federal judges grapple with issues left unaddressed by Supreme Court precedent and are offered little guidance concerning whether a majority will support the same position under a different fact pattern.Footnote 6 Under this condition of uncertainty, there may be greater potential for goal conflict between district court judges and circuit court superiors. In contrast, when directives from the Supreme Court are clear, goal conflict between circuit court and trial court judges becomes less relevant as both will be more likely to discern the connections between the case at hand and Supreme Court precedent. In light of these theoretical propositions, we construct our hypothesis in terms of Supreme Court consensus, on grounds that dissents and concurrences blur the Supreme Court's policy preferences and thus complicate implementation by the lower courts.

H11: As justice support for the majority position on the Supreme Court increases, a circuit panel is less likely to reverse the district court decision.

Data and Methods

To evaluate these hypotheses empirically, we sampled published civil rights and civil liberties decisions of the U.S. Courts of Appeals from 1971–1999. By selecting a defined issue area, we are more confident that our analysis includes roughly comparable cases. In addition, civil rights and civil liberties cases represent a policy area in which judges are more likely to hold specific preferences and are more likely to be aware of preferences held by others in the federal judicial hierarchy. Finally, in civil rights cases, it has been observed that lower court judges' preferences have the potential to contribute to a lack of uniformity in federal law (Reference Richardson and VinesRichardson & Vines 1970; Reference PeltasonPeltason 1961). As described by Judge Reference WisdomJohn Minor Wisdom, “civil rights cases reflect the customs and mores of the community as well as the legal philosophy of the individual judges called upon to adjudicate the controversies … this is where localism tends to create wide differences among our courts” (1967:419). Although this quote relates to the courts’ role in desegregation during the 1960s, the “agency problem” described by Judge Wisdom may also apply to contemporary cases in the lower federal courts. In the last few decades, the passage of numerous civil rights statutes has contributed to lower court involvement in resolving disputes covering a wide range of discriminatory activities. The dramatic change in civil rights laws over the last few decades has likely contributed to greater legal uncertainty in the area. We are aware, however, that our findings may not extend to other substantive areas.

Our sampling frame included all published decisions in civil rights and civil liberties cases from each circuitFootnote 7 for each year from 1971–1999. From that population we drew a systematic sample to yield 20 cases per circuit/yearFootnote 8 for the 29-year period. Observations in the models were weighted to account for this sampling design.

Dependent Variable

Since we are interested in assessing those factors that affect the outcome of appellate review, our dependent variable is the disposition of the caseFootnote 9 by the circuit court. If the panel voted to reverse the district court, the dependent variable was coded as 1.Footnote 10 If the panel voted to affirm, the dependent variable was coded as 0.Footnote 11 Excluded are decisions where the panel affirmed in part and reversed in part and cases where the district court's policy position could not be unambiguously coded. Given that our dependent variable is dichotomous, we utilize a logit model to estimate the effects of the independent variables on the likelihood of reversal.

Independent Variables

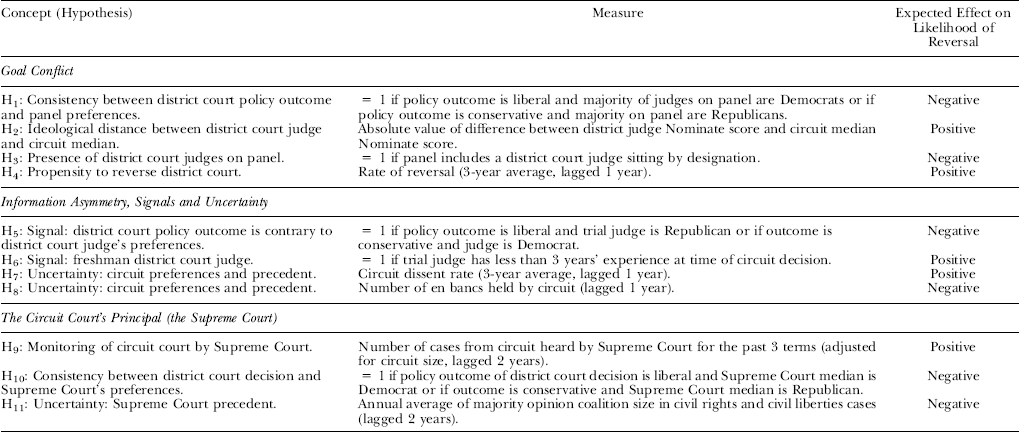

The hypotheses outlined above suggest that we test for the influence of variables associated with the relationship between the circuit court and the district court. Those hypotheses dealing with goal conflict required that we develop measures of judicial policy preferences to compare across courts and to construct measures of ideological consistency with case outcomes. When possible, we utilized continuous measures of preferences. In two measures (see Table 1, H2), we rely on Nominate scores (Reference PoolePoole 1998) of the appointing president to measure federal judges’ policy preferences. These “common-space” scores provide an estimate of presidential ideological preferences that is continuous and can be compared directly over time (Reference PoolePoole 1998). For other variables, we needed to use a dichotomous measure of preferences. In those instances, we rely on the party affiliation of the appointing presidentFootnote 12 and assume that those appointed by Democrats will be more likely to support liberal policy and that those named by Republicans will be more likely to hold conservative views. For several variables (see Table 1, H1 and H10), we also used these indicators of ideology to compute measures of ideological consistency between the policy direction of the trial court's decision and the principal's preferences.Footnote 13 Although the full range of coding rules cannot be described here, we followed the conventions of the Multi-User Database of the U.S. Courts of Appeals. For example, cases were coded as “liberal” if the judge supported plaintiffs who alleged a civil rights violation or claimed an unconstitutional infringement of their civil liberties. The policy advocated by the district court is coded from the appellate court's decision. In this respect, we coded the outcome of the primary issue that concerned the circuit panel. The details of the coding process are outlined in Table 1.Footnote 14 Summary statistics and a correlation matrix for the variables are presented in the Appendix.

Table 1. Independent Variables and Measures

In addition to the data sources described above, information on en bancs and reversal rates (of district courts) were collected from various annual reports of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. To estimate dissensus, we utilized the Multi-User Database on the U.S. Courts of Appeals to calculate an annual dissent rate (for all issue areas) and then averaged the rate over a three-year period. Data on the number of cases heard from each circuit by the Supreme Court were found in the U.S. Supreme Court Judicial Database, compiled by Reference SpaethHarold Spaeth. After summing the number of cases heard from the circuit over a three-year period, we divided that figure by the number of authorized judgeships for the circuit to adjust for circuit size.

Results

The results of the logit model provide support for several of our hypothesized relationships.Footnote 15 In terms of goal conflict, appeals court panels were more likely to affirm when the policy advocated by the trial court was consistent with the preferences of at least two circuit court judges on the panel. The predicted probabilityFootnote 16 of reversal falls from 0.36 to 0.29 when the policy advocated by the district court shifts from one that does not support the preferences of the panel majority to a position that is consistent with the preferences of the panel. The ideological distance between the trial court judge and the center of the circuit court also affected the likelihood of reversal. Cases from trial court judges whose views placed them closer to the ideological center of the circuit were more likely to be affirmed; those from judges whose views diverged from the circuit majority's preferences were more likely to be reversed. Relative to goal conflict involving the panel's preferences, however, the effect of this variable was somewhat limited. And when the panel included a district court judge sitting by designation, there appeared to be a slight tendency to affirm as well; however, the estimated relationship was statistically significant at the 0.07 level.

The degree to which conflict exists between the reviewing panel and the district court judge appeared to be shaped by long-term interaction between district courts and appeals court judges on the entire circuit. Circuits that tended to defer to the decisions of trial court judges in the three years prior to the case being reviewed were less likely to reverse in the individual case. The likelihood of reversal was significantly higher in cases decided in circuits with a predisposition to reverse district courts generally.

Table 2. Logit model Likelihood of Reversal by Circuit Court in Civil Rights and Liberties Decisions, 1971-1999

N = 4,585 (weighted: actual number of observations is 4,971).

LR chi2(11) 5 159.2, p <0.000.

Mean of dependent variable: 0.376.

† p<0.07, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Change in predicted probability is calculated by holding all variables at their observed mean or modal value and allowing each variable of interest to range from their minimum and maximum values.

We also hypothesized that the outcome of monitoring would vary due to informational asymmetries that exist between trial courts and appeals courts. Cases were slightly more likely to be affirmed when the district court judge decided contrary to his or her own preferences. In contrast, cases from relatively new trial court judges were no more likely to be reversed than those cases that originated in district courts presided over by more experienced jurists.

Uncertainty also appears to shape the need for, and direction of, monitoring by the appeals courts. In particular, increases in the circuit's dissent rate contributed to the likelihood of reversal to a statistically significant degree. On the other hand, the frequency of en banc hearings did not affect the outcome of appellate court monitoring in our model to a statistically significant degree. A number of reasons may account for this nonfinding, including the possibility that circuits use “informal” en bancs to resolve intra-circuit conflict in precedent (Reference WasbyWasby 2000). It is also possible that many decisions to rehear cases en banc represent efforts by a circuit to signal a conflict with another appeals court.

The effect of the circuit court's principal, the Supreme Court, is also evident in the logit model results. The appeals court panel was much more likely to affirm when the district court's policy was consistent with the majority position on the High Court. The predicted probability of reversal falls from 0.52 to 0.36 when comparing appellate review of district court decisions that are not consistent with the majority position of the Supreme Court against those that do support the majority position on the High Court. In addition, the level of attention given to the circuit by the Supreme Court appears to affect interactions between the lower courts to a statistically significant degree. As the number of cases accepted by the Supreme Court from a circuit increased, in subsequent years, district court decisions in that circuit were more likely to be reversed. In contrast, the size of the Supreme Court majority in civil rights and civil liberties decisions was not related to the outcome of appellate review in the lower courts.Footnote 17

Discussion

Although the effects for several hypothesized relationships were relatively weak (or nonexistent), overall the results of the statistical model clearly suggest that the three levels of the federal judicial system function in an integrated fashion, with institutional characteristics at all levels affecting the outcomes in individual cases. Although the federal courts are certainly decentralized, our results reveal that centripetal forces serve to enhance cohesive decision making in many circumstances. For example, circuit courts tend to reverse decisions below in order to further their own preferences as well as the preferences of the circuit's principal at the Supreme Court. This process no doubt serves to rein in errant district court judges whose decisions fail to conform to their superiors' expectations, and thus to promote consistent outputs. Moreover, when a circuit demonstrates cohesive precedent and communicates its preferences clearly through consensual decision making, it appears to enhance the lower court's ability to satisfy the circuit by rendering decisions that are more frequently affirmed. In contrast, we were not able to detect any effects stemming from fragmented decision making at the Supreme Court, a finding that is consistent with existing research concerning the impact of opinion “strength” on the implementation of Court policies (Reference Pacelle and LarryPacelle & Baum 1992; Reference JohnsonJohnson 1979).

Our results also indicate that district court judges may be sensitive to their principal's principal at the Supreme Court. As the Supreme Court increases its scrutiny of a circuit, the district court appears to render more decisions that require reversal. As we proposed in our hypotheses, it is possible that reversal is more frequent in these circumstances because the district court judge has recognized the Court's dissatisfaction with the circuit. In these instances, district court judges may not be convinced of the finality or authority underlying circuit precedent and thus depart from the circuit's preferences. The finding also may simply reflect on a circuit's ability to develop sufficiently clear legal policy on civil rights and civil liberties issues. In circuits where panels do not offer clear guidance, district court judges are more likely to commit reversible error and the Supreme Court is more likely to feel compelled to resolve confusion surrounding the circuit's legal policy. Under either interpretation, the incentive of the district judge to adhere to a circuit's policy mandates will be expected to vary with Supreme Court attention to that circuit.

Our empirical analysis also reinforces the conclusion that principal-agent theory is a useful tool to analyze the relationship between the district and circuit courts, as well as the relationship between the circuit courts and the Supreme Court. By directing attention to the role of institutional influences, particularly those associated with hierarchical organizations, this approach extends beyond general preference-based models to offer new insights on interactions between levels of the judiciary. Previous studies have employed formal models that suggest the utility of using principal-agent theory to understand relationships within the judicial hierarchy and there has been some empirical analysis that is consistent with the predictions derived from such formal theories. But the previous empirical support has been thin, generally limited to a single narrow issue area and/or a single dyad within the three-layer system of federal courts. The present study contributes to previous work by considering general relationships between the courts of appeals and the district courts as are conducted within the parameters established by the principal of both courts, the U.S. Supreme Court. Although we did not construct a formal principal-agent model, we nevertheless rely on the insights offered by principal-agent theory to develop our hypotheses related to the theoretical concepts of goal conflict and information asymmetry. Our findings regarding the importance of goal conflict suggest that federal judges at all levels are guided by their policy preferences in the decision-making process.Footnote 18 Additionally, concern for superiors’ preferences also affected case outcomes. District and circuit judges are apparently not single-minded attitudinal actors; they are institutional players who attempt to render decisions that are acceptable at all levels of the hierarchy.

Moreover, it appears that informational resources are determinants of the appeals process. Due to information asymmetries that disadvantage the appellate judges, circuit judges appear to rely on signals or cues based on the ideological orientation of the district court. As earlier research has revealed in the Supreme Court review process (Reference Cameron, Segal and SongerCameron, Segal, & Songer 2000), circuit judges are more likely to affirm decisions below that are inconsistent with the preferences of the district judge. Thus, appeals court panels may have more faith in the legal accuracy of decisions that are ideologically inconsistent with the district judges’ preferences. In addition, district court judges are more likely to be reversed in circuits characterized by dissensus, which elevates the district judge's level of uncertainty regarding the circuit's preferences and enhances the likelihood that he or she will render decisions that are reversed on appeal. Thus, interactions between the circuit and district courts appear to be shaped by information asymmetries at both levels of the lower federal judiciary.

In several important respects, therefore, agency theory presents an improvement on a more simplified model of appellate review based solely on attitudinal factors. By highlighting the importance of information asymmetries and uncertainty in the context of appellate review, agency theory expands on existing attitudinal explanations of judicial behavior. Most importantly, it allows for the generation and testing of hypotheses reflecting institutional pressures and cross-pressures on judges serving in the lower tiers of the federal judiciary. In our study, certain hypotheses rest on theoretical assumptions that are not simply attitudinal in nature. For example, we explored the complications that arise when an agent is faced with potentially conflicting signals from multiple principals. Here we found that the degree to which the Supreme Court has monitored the circuits through certiorari review, and the level of consistency between district court and Supreme Court preferences, were important influences on the circuit's decision to affirm or reverse.

Finally, this research highlights the importance of studying principal-agent relations at all levels within a bureaucratic organization such as the federal courts. By taking into account the potential dynamics generated by successive layers in the appeals process, this research revealed that the acts of judicial agents are not being shaped solely by immediate superiors, but rather are structured by the entire judicial hierarchy. Moreover, our results indicate that the influence of the ultimate superior at the Supreme Court may be moderated as its commands are filtered through the individual circuits to the district courts.

Appendix: Summary Statistics