Traditionally, the Formative period (1000 BC–AD 900) is defined as a time of profound socioeconomic changes characterized by intensified sedentarism, control of production sources and processes, concentration of political power, and the emergence of structural and social inequality (Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Agüero, Valenzuela, Falabella, Uribe, Sanhueza, Aldunate and Hidalgo2016). These changes exacerbated tensions between individuals that may have triggered social conflicts in the Formative period in northern Chile (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020). Their manifestations can be studied through cases of physical violence, how this violence was produced, and the spaces in which it occurred.

The study of violence in bioarchaeology attempts to understand its role in intergroup relations (Martin and Harrod Reference Martin and Harrod2012). Various studies in the south-central Andes present the evidence of physical violence, attributing it to different types of conflicts, especially during the Late Intermediate period (LIP; AD 900–1450; e.g., Arkush and Tung Reference Arkush and Tung2013; González-Baroni et al. Reference González-Baroni, Aranda and Luna2019; Pacheco and Retamal Reference Pacheco and Retamal2017). Evidence and investigations are scarcer for the Formative period (Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2004; Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Seldes and Bosio2012; Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021; Torres-Rouff et al. Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018).

In the Atacama Desert of northern Chile, the study of violence has concentrated on those regions that make up the traditional focus of Chilean archaeology, such as San Pedro de Atacama and Arica (Figure 1). These investigations incorporated evidence of trauma in mummified and skeletonized bodies, weaponry, architecture, and rock art (e.g., Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2004, Reference Lessa and de Souza2006, Reference Lessa and de Souza2007; Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Monsalve and Marquet2020, 2021; Torres-Rouff and Costa-Junqueira Reference Torres-Rouff and Costa-Junqueira2006; Torres-Rouff et al. Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018). The evidence of violence is generally explained by set types of interpersonal conflict. Most frequently cited are war, ritual battles, ambushes of locals by strangers, and the role played by state entities with respect to local groups, such as that of Tiwanaku in relation to the communities of San Pedro de Atacama (Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2004).

Figure 1. The south-central Andean area, showing the location of the Tarapacá 40 cemetery.

Different scenarios of interpersonal violence, in which skeletons of women appear to show evidence of violent injuries, tend to be attributed to ritual confrontations or domestic violence, without much examination of what these categories entail (e.g., Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2006; Pacheco and Retamal Reference Pacheco and Retamal2017; Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021). These categories in the study of violence combine social imaginaries biased by colonialist, androcentric, and Western ontology (García-Peña Reference García-Peña2016). We therefore question the categorization of violence as personal or domestic in archaeology because it ignores the political sphere (Millet Reference Millet2010).

In this article, we present a bioanthropological analysis of a female body associated with physical violence, which had been buried in the Tarapacá 40 (Tr-40) cemetery, dating to the Formative period. We evaluate this individual through her osteobiography, an approach for the reconstruction of the microhistory of past subjects (Hosek Reference Hosek2019). We focus on evidence of osteological particularities, cranial traumas, and diet, as well as associated burial offerings, while considering her sociohistorical context and her relationship with the rest of society.

The sociopolitical context that developed during the Formative period in the Tarapacá region provides various lines of evidence that can be used to study violence and social conflict. In addition, the Tr-40 cemetery's archaeological and bioanthropological remains are exceptionally well preserved. Therefore, this female body offers a unique opportunity to investigate the relationship between physical violence and social conflict.

Historical and Social Setting

The Tarapacá region is part of an ecological and cultural macro area located in the southern portion of the Western Valleys of the south-central Andes (Figure 1). It is bounded by the Camiña River in the north, the Loa River in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the west, and the Andes in the east (Maldonado et al. Reference Maldonado, de Porras, Zamora, Rivadeneira, Abarzúa, Falabella, Uribe, Sanhueza, Aldunate and Hidalgo2016). Varying landscapes and ecosystems are found in this region: the coast of Pacific Ocean and the Coastal Cordillera; the Pampa del Tamarugal with its valleys, ravines, and oases; the precordillera; and, finally, the altiplano in the Andes at 2,500–4,000 m asl (Santoro et al. Reference Santoro, Capriles, Gayo, de Porras, Maldonado, Standen and Latorre2017). Today, the Tarapacá region is characterized by extreme aridity and scarce vegetation, but 2,000 years ago the valleys around the ravines contained forests of Prosopis, reflecting the greater availability of water (Maldonado et al. Reference Maldonado, de Porras, Zamora, Rivadeneira, Abarzúa, Falabella, Uribe, Sanhueza, Aldunate and Hidalgo2016).

The Tr-40 cemetery (1000 BC–AD 600) is located on the north side of the low course of the Tarapacá ravine, and it is associated with the Formative settlements of Pircas-1 (370 BC–AD 350) and Caserones-1 (AD 20–1020; Núñez Reference Núñez1982, Reference Núñez1984; Pellegrino et al. Reference Pellegrino, Adán and Urbina2016; True Reference True, Meighan and True1980; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015). The individual whom we analyzed comes from tomb 1 in sector Y, which represents the late component of the cemetery and is associated with the Caserones village during the Late Formative (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015:Note 1).

The Late Formative period of Tarapacá (ca. AD 200–900) is contemporary with the Middle period described in other areas of the Western Valleys, which is usually characterized according to the altiplano presence or influence on local cultural developments relating to incipient agriculturization, such as in the Arica Valley (Rivera Reference Rivera, Rivera and Kolata2004). This definition matches most classic archaeological proposals for the Atacama Desert, which are influenced by the Neolithic model (e.g., Núñez Reference Núñez, Hidalgo, Schiappacasse, Niemeyer, Aldunate and Solimano1989; Muñoz Reference Muñoz2004; Rivera Reference Rivera, Rivera and Kolata2004). According to this definition, local populations—with roots in ancient coastal traditions—had little agency in the cultural processes that led to an agricultural and village lifestyle. These changes would have been mediated by the presence of colonies from the highlands who had been influenced by more complex economic and political formations. In recent years, this proposal has been modified to some extent, giving greater agency to the Formative coastal and local populations in their social and economic transformations (e.g., Muñoz Reference Muñoz2019; Núñez and Santoro Reference Núñez and Santoro2011).

An alternative model has been proposed for the Formative period in the Tarapacá region, further emphasizing the agency of communities and the importance of understanding local processes from the perspective of the settlement's social life (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020). The groups that occupied the Pampa del Tamarugal had strong identity links with the coastal people that developed a hunter-gatherer-fisher lifestyle (Santoro et al. Reference Santoro, Capriles, Gayo, de Porras, Maldonado, Standen and Latorre2017; Uribe and Adán Reference Uribe and Adán2012). The Tr-40 cemetery has evidence of these links in the form of resources and objects associated with the coast, and the stable isotope analyses of the bioanthropological remains show individuals who were related to both ecozones: the Pampa del Tamarugal and the coast (Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015).

The Formative processes in Tarapacá reflect a society with a social and political organization based on kinship relations between autonomous or segmentary units/territories, which reproduced identity ideals through the cult of the ancestors as a means of territorial and political reaffirmation (Adán et al. Reference Adán, Urbina, Uribe, Nielsen, Rivolta, Seldes, Vázquez and Mercolli2007; González-Ramírez et al. Reference González-Ramírez, Sáez, Herrera-Soto, Leyton, Miranda, Santana-Sagredo and Uribe-Rodríguez2021). During the Late Formative, social complexity is evident in such places as the Caserones village with its restricted domestic and public spaces, in the agricultural fields connected with silvicultural production areas, and in ceremonial spaces such as tumuli and the geoglyphs in the surrounding hills (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020).

The people buried in Tr-40 likewise embody the complexity of this period through their diverse types of cranial modifications and hairstyles (Arias and Herrera Reference Arias and Herrera2012). Their funerary vestments also suggest individual distinctions, as well as a performativity that was possibly displayed in ceremonial settings (Agüero Reference Agüero2012). After studying the bioanthropological remains of Tr-40, González-Ramírez and colleagues (Reference González-Ramírez, Sáez, Herrera-Soto, Leyton, Miranda, Santana-Sagredo and Uribe-Rodríguez2021) proposed the presence of social/sex regulation that affected different agents, such as control over the procreative labor performed by women as a mechanism to maintain social reproduction.

Therefore, social complexity in Tarapacá is understood as the emergence of the organization and reproduction of a new social order. This led to technological changes, labor specialization, and a system of relationships between different regions of the Andes for the exchange of goods and persons, as well as for the enhancement of social or kinship alliances through reciprocity and exchange (Núñez and Santoro Reference Núñez and Santoro2011; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020). This increased social complexity brought with it growing inequality and tensions, as reflected in evidence of physical violence documented in some areas of northern Chile (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021; Torres-Rouff et al. Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020:18). These Formative period processes were created collectively from the relations of reciprocity and power between persons and their environment and from diverse ways of conceiving the world, as mediated by their historical and local trajectories (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020).

Theoretical Approach

Here, we understand power not as a force that comes from an upper hierarchy of society (e.g., elites) but as a human phenomenon that permeates all aspects of social life and is reproduced in discourse, quotidian practices, and corporeality (Foucault Reference Foucault1990:112–113). Social inequality fundamentally arises from the daily relationships of the bodies/subjects (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1997). Therefore, we propose that the woman of Tr-40 whom we analyze more closely approximates how some individuals, especially those in nonprivileged situations, lived during the Formative period.

Our principal theoretical approach is based on social bioarchaeology and feminist archaeology (e.g., Geller Reference Geller2008; Vila-Mitjà Reference Vila-Mitjà2011). Both frameworks allow us to understand this individual's life in a broader context and to relate her role as a member of a specific collective to a shared social and historical background. We also incorporate the methods of osteobiography to construct a narrative about the life and death of the woman through the study of her body. The body as materiality is made up of different layers of biological traits and biocultural processes (Geller Reference Geller2008). On a larger scale, the body with other subjects and material aspects of the social configuration constitute relational nodes with overlapping temporalities, materials, and biographies (Hosek Reference Hosek2019).

We use microhistory as a complementary approach because it converges with osteobiography in the scale of analysis; both argue that close examination of an individual subject has the potential to reveal previously overlooked phenomena and connections to wider historical processes (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1994; Hosek Reference Hosek2019). The human body acts as a locus of multiple intersecting histories that are constructed between individuals, who are considered nodes within networks of relationalities (Robb and Pauketat Reference Robb, Pauketat, Robb and Pauketat2013). Thus, interactions at the local scale are together constantly negotiating and transforming history on the large scale (Hosek Reference Hosek2019). Osteobiography and microhistory enable an emphasis on the agency of people in the past, especially subaltern subjects, and their active roles in shaping history: by so doing, they critique dominant narratives and offer alternative understandings of the past (Ginzburg Reference Ginzburg1994; Hosek Reference Hosek2019).

Materials and Methods

The Tr-40 cemetery was excavated in the 1960s and early 1980s (Núñez Reference Núñez1982). Its archaeological materials were deposited in the Canchones Collection of Universidad Arturo Prat, and the human remains were stored at the Departamento de Antropología of Universidad de Chile. Permissions to study the offerings and human remains were granted by the authorities of both institutions.

The individual studied (ID: B2140) is mostly skeletonized and complete. The postcranial skeleton is in a good state of preservation, but the cranial vault is fragmented due to postdepositional events. The fragments of the ectocranium were then refitted and restored, with the aim of recording its bioanthropological features. The pieces of the cranial vault were joined using adhesive paper tape (3M micropore). Later, 3D models were developed using stereophotogrammetry, employing a Canon Eos Rebel 650D camera for capture, Agisoft (version 1.2.6, 2016) for 3D reconstruction, and Meshmixer software for editing.

The skeletal remains were analyzed using standard bioanthropological methods for sex determination and age estimation (Buikstra and Ubelaker Reference Buikstra and Ubelaker1994; Walker Reference Walker2005; Walrath et al. Reference Walrath, Turner and Bruzek2004). Stature was estimated using the maximum length of the femur and the tibia following Pomeroy and Stock (Reference Pomeroy and Stock2012). Artificial cranial modification was classified based on Dembo and Imbelloni (Reference Dembo and Imbelloni1938). Paleopathological signs were identified macroscopically following Ortner (Reference Ortner2003), and we observed four dental parameters: dental attrition, caries, antemortem tooth loss, and periapical lesions (Hillson Reference Hillson1996; Scott Reference Scott1979; Smith Reference Smith1984).

An essential part of the study was the analysis of cranial trauma. The lesions were described based on published protocols for trauma analysis, specifically cranial blunt force injuries (Figure 2; Berryman and Symes Reference Berryman, Symes and Reichs1998; Judd and Redfern Reference Judd, Redfern and Grauer2012; Kranioti Reference Kranioti2015; Lovell Reference Lovell1997; Sauer Reference Sauer and Reichs1998; Spencer Reference Spencer2012; Symes et al. Reference Symes, L'Abbé, Chapman, Wolff, Dirkmaat and Dirkmaat2012). To increase the accuracy of the assessment, four physical anthropologists described and analyzed the cranium when it was still fragmented and again after it had been refitted. First, each researcher recorded the fractures separately, and then they discussed their diagnoses, excluding taphonomic fractures following Sorg (Reference Sorg2019).

Figure 2. Methodological criteria applied for recording and analyzing cranial trauma.

Samples of a left rib fragment and of a second molar were obtained for radiocarbon dating and for carbon and nitrogen stable isotope analysis. The biochemical analysis was performed by Beta Analytic, Miami. The 14C date was calibrated using the SHCal20 atmospheric curve (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg, Timothy Heaton, Jonathan Palmer and John Southon2020) in OxCal v 4.4.2 (Bronk Ramsey and Lee Reference Bronk Ramsey and Lee2013). Finally, we included information on the grave goods recovered from the tomb.

The Body as a Story of Life

The osteological remains analyzed belonged to a female individual whose age at the time of death was between 35 and 45 years (Supplemental Table 1).Footnote 1 The individual lived in the Atacama Desert during the Late Formative period (cal AD 427–594; 1580 ± 30 AP; 95.4% hpd; Figure 3). Based on this date and the location of her tomb (T1-SY), this person may have been a member of the community associated with the Caserones village, which was occupied continuously until the end of the Formative period (Pellegrino et al. Reference Pellegrino, Adán and Urbina2016).

Figure 3. Calibrated radiocarbon date of individual B2140 (Beta-355779; bone collagen).

Artificial cranial modification (ACM) was a recognized cultural practice in northern Chile (Díaz-Jarufe et al. Reference Díaz-Jarufe, Pacheco-Miranda and Retamal-Yermani2018). In the Tr-40 cemetery, the most common ACMs were circular oblique and tabular oblique (Arias and Herrera Reference Arias and Herrera2012). The woman's head was molded intentionally, causing a tabular oblique cranial modification (Dembo and Imbelloni Reference Dembo and Imbelloni1938). We compared the ACM types of Tr-40 with those documented in the contemporary cemetery of Cáñamo-3, located on the coast and about 80 km from the Tarapacá ravine (Figure 1). Both cemeteries have similar types of ACMs (Arias and Herrera Reference Arias and Herrera2012; Núñez and Moragas Reference Núñez and Moragas1977). This similarity suggests a relationship between these populations, which was also proposed based on the analysis of stable isotopes from both cemeteries that indicated a change of residence—from the coast to the Pampa del Tamarugal, or vice versa—mostly by women (Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Herrera and Uribe2012, Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015).

When we assessed the woman's state of health, we found that her temporomandibular joint was severely affected, which means that she likely had osteoarthrosis of the masticatory apparatus. The osteoarthrosis was probably related to advanced dental wear (Supplemental Figures 1 and 2). Both may be related to the food that she consumed during her life or to some kind of activity, which in conjunction with her age could produce the severity of these indicators.

The δ13C and δ15N isotope values obtained from the tooth and bone samples do not differ (Table 1), which indicates that she consumed a similar diet throughout her life. The isotope data show that she ate food from different sources. The principal source was probably wild and cultivated C3 plants (e.g., algarrobo, chañar, molle, quinoa, squash) from the Pampa del Tamarugal, whereas C4 resources (most likely maize) were a more minor source (Holden and Núñez Reference Holden and Núñez1993; Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015). She also consumed food that probably came from the Pacific Ocean, as shown by the δ15N values. This interpretation is supported by the zooarchaeological evidence of fish and shellfish found at Tr-40 and related domestic sites and the diet indicated by stable isotope analysis of other individuals from this cemetery (Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Herrera and Uribe2012, Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015). However, the marine diet input was not considerable, and it was likely complemented by terrestrial resources. Thus, a variety of foods were consumed in Tarapacá during the Formative period (García et al. Reference García, Vidal, Mandakovic, Maldonado, Peña and Belmonte2014; Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015).

Table 1. Stable Isotope Analysis Results for Bone Collagen and Apatite.

The dental wear, as well as the chipping and the groove observed in one of her molars, suggests that she chewed hard products constantly (Supplemental Figure 3). The presence of mortars and handstones in sites of the Tarapacá region during the Formative period shows that the production of ground food, such as flour, was common (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Angelo, Capriles, Castro, de Porras, García and Gayo2020). This ground food may have contained abrasive particles from the mortar, which can contribute to greater dental wear or chipping of the dental enamel (Hillson Reference Hillson1996:231). The fibers and fruits of various types of vegetables found in these sites suggest the consumption and use of wild plants as raw materials for different purposes (e.g., basketwork, building material), for which the teeth were probably used as tools.

Traditional work associated with women is the production of chicha, reported ethnographically and proposed for many archaeological populations (Hayashida Reference Hayashida2008; Hubbe et al. Reference Hubbe, Torres-Rouff, Neves, King, Da-Gloria and Costa2012). This process required constant use of the masticatory apparatus. The product generated from the chewing of seeds (e.g., algarrobo, maize, molle) accelerated the drink's fermentation, because the amylase enzymes contained in the saliva contribute to the separation of the starch into simpler sugars (Smalley and Blake Reference Smalley and Blake2003). Consequently, the dental features documented here may reflect the effect of the woman's age on dental attrition, the consumption of hard fruits and foods with abrasive particles, and the parafunctional use of her teeth for different tasks.

The degenerative joint disease (DJD) recorded in the spine and left tibia indicate biomechanical stress, especially in the lower back and knees, but the expression of these signs was still incipient at the time of death. These conditions may have been generated by repetitive movements during her life—for example, poor posture or bending down without bending her knees to pick up objects—or doing work at ground level (Larsen Reference Larsen2015). Adults of both sexes from Tr-40 exhibit similar levels of DJD in the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae and in the lower limb, which are increased in individuals older than 40 years old (Herrera Reference Herrera2010). This information, together with that obtained from the materiality of the cemetery and Caserones-1 (e.g., Núñez Reference Núñez1982; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015), suggests that individuals carried out different activities related to the gathering and transport of products; engaged in repetitive work such as in the textile industry, agricultural activities, and food processing through grinding; and were mobile.

The woman does not present osteological signs associated with specific diseases. Similar results were observed in the other skeletons exhumed from Tr-40 (Arias and Herrera Reference Arias and Herrera2012). However, the absence of macroscopic signs in the bone does not necessarily imply good health or the absence of disease (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Milner, Harpending and Weiss1992). Studies on mummies from Tr-40 showed a high prevalence of respiratory disease, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis (Allison et al. Reference Allison, Gerszten, Munizaga, Santoro, Mendoza and Buikstra1981; Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Allison, Gerszten and Arriaza1983), and high infant mortality (González-Ramírez et al. Reference González-Ramírez, Pacheco-Miranda, Sáez and Arregui-Wunderlich2019). Chagas disease, blastomycosis, salmonella, and parasitic infections were also documented (Allison et al. Reference Allison, Gerszten, Jean Shadomy, Munizaga and González1979; Fontana et al. Reference Fontana, Allison, Gerszten and Arriaza1983; Ramirez et al. Reference Ramirez, Herrera-Soto, Santana-Sagredo, Uribe-Rodríguez and Nores2021; Rothhammer et al. Reference Rothhammer, Standen, Nuñez, Allison and Arriaza1984).

These data suggest that poor sanitary conditions for the Formative period—probably related to population growth, overcrowding, poor hygiene, food or water contamination, and new zoonotic relationships—generated favorable conditions for contagion by infectious diseases. Thus, the daily conditions of the Tr-40 woman were characterized by the presence of contagious diseases among people and animals, associated with a more sedentary lifestyle that included domestication of animals and a higher population density. Even had she suffered any of these illnesses, they were not the cause of her death.

Social Life and a Violent Death

The organization of Andean societies, such as the Aymara communities in northern Chile, is modulated by life cycles shaped by gender relations that create and regulate social, economic, political, and religious life. The life cycle is determined by individuals’ social phase/age and the role they have in their social networks (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2020). We do not intend to make a direct comparison between contemporary Andean societies of the Atacama Desert and the communities that inhabited it in the past. However, looking at the present allows us to understand that the life of an individual is built based on multiscalar cultural components that cross and shape his or her historicity and identities.

This woman's years from childhood to adulthood occurred in the same environment in which she died, as suggested by the isotopic signals. The δ13C and δ15N isotope values show a close relationship with the resources of the Pampa del Tamarugal and occasionally with the coast (Santana-Sagredo et al. Reference Santana-Sagredo, Uribe, Herrera, Retamal and Flores2015), as is also suggested by her ACM. Her appearance would not have stood out within the population, given that her ACM type was described for most subjects buried in Tr-40 (Arias and Herrera Reference Arias and Herrera2012). In addition, her lifestyle-related osteological and dental markers show similarities with the rest of the individuals of Tr-40, which could suggest she had an aesthetic and performance of quotidian practices that did not differ radically from those of the rest of the inhumed. Therefore, the social role of the woman was likely similar to that of her congeners, and she may have experienced the same stages of socializing as women of a similar age.

In this historical context, it is possible that society expected a woman over 35 years old to have completed certain stages of her life cycle, such as reproduction and caregiving. In Aymara society, the phase of the life cycle associated with reproduction has a name (Tayka) that is linked only to women (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2020). González-Ramírez and colleagues (Reference González-Ramírez, Sáez, Herrera-Soto, Leyton, Miranda, Santana-Sagredo and Uribe-Rodríguez2021) propose that, for the Formative period of Tarapacá, women's labor included biological reproduction as part of the social commandment to produce new members. Therefore, her age at death indicates that she had lived through most of the stages of social life in her community, and her identity construction was based on gender and intersubjectivities appropriate to the time and space in which she lived (Toren Reference Toren2012).

This woman, however, met a sudden and violent end, to judge by the trauma recorded on her cranium. Three fractures were recorded on the left parietal and four on the right parietal and occipital bones (Figure 4; Supplemental Table 2; Herrera Reference Herrera2020). The V-shaped pair of traumas on the left parietal suggest that these blows were struck with an object with a rounded (not sharp), angled edge (Supplemental Figure 4). The similarities in the shape, size, and depth of these two lesions indicate the same angled object was likely used. The other blow to the left parietal shows a smaller depression and a different shape from the first two; hence the blow was probably struck tangentially or with less force than the first two injuries.

Figure 4. Drawings of the cranial fractures in different views (Tr-40, individual B2140). Numbers indicate impact points.

These three blows caused delamination of the inner table (Supplemental Figure 4), which may have produced intracranial hemorrhaging and loss of consciousness. If the woman lost consciousness, she probably fell, which may have resulted in the radiating and concentric fractures observed in the right parietal caused when her head struck the ground.

The location of the trauma in the lower part of the occipital bone (fragmented by taphonomic factors and partially reconstructed by us) suggests that she was crouching and looking down or lying on the ground when she was struck (see Herrara [Reference Herrera2020] for a 3D model of the skull). These fractures are consistent with successive blows with a blunt, dense object of a small size and undefined shape. These were probably the last blows she received because some of the radiating fractures stop at the depressed fracture in the left parietal, indicating that the earlier trauma stopped the propagation of these occipital fractures (Kranioti Reference Kranioti2015).

Therefore, these traumas are described as the perimortem type; that is, any sign or response to an external stress on fresh bone (wet and greasy) that still maintains its viscoelastic properties (Symes et al. Reference Symes, L'Abbé, Chapman, Wolff, Dirkmaat and Dirkmaat2012). The absence of antemortem fractures related to violence may indicate that she had never been exposed previously to violent events. However, injuries related to physical attacks do not always affect bone tissue. Soft tissue, in contrast, is more likely to be damaged by physical attacks (Judd and Redfern Reference Judd, Redfern and Grauer2012).

We discarded the differential diagnosis of accidental injuries because of the absence of trauma to the postcranial skeleton and the large number of lesions in the ectocranial area, as well as their morphological features. Indeed, previous studies considered multiple cranial traumas as indicators of physical violence (e.g., Lovell Reference Lovell1997; Wedel and Galloway Reference Wedel and Galloway2014). The location of the injuries (lateral and posterior sides of the skull) indicates an attack from behind by one or more assailants. Further, the number of blows suggests the intention to kill the victim.

The traumas of this woman are unique when compared with the pattern of injuries observed in other bodies from Tr-40. Adults of both sexes show injuries associated with nonlethal violence, such as healed fractures in the face probably caused by blows with a fist (Table 2). Some individuals also have oval and depressed fractures on the cranial vault but smaller than those of this woman (Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Uribe, González-Ramírez, Sáez and Santana-Sagredo2019).

Table 2. Frequency of Healed Cranial Fractures in the Tarapacá 40 Cemetery.

Note: Data from Herrera and colleagues (Reference Herrera, Uribe, González-Ramírez, Sáez and Santana-Sagredo2019). A significance level of p < 0.05 was used.

We discarded the possibility of a ritual death in this case because there is no evidence of traumas associated with human sacrifice anywhere else in the cemetery, as is described for other regions of the Andes (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021). We also rejected the possibility that the woman's injuries were caused in the context of raids or warlike events due to the absence of perimortem violence–related injuries in any other individual from Tr-40 or of differential funeral treatment, in contrast to other contexts of lethal violence in northern Chile (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Arriaza, Santoro, Romero and Rothhammer2010).

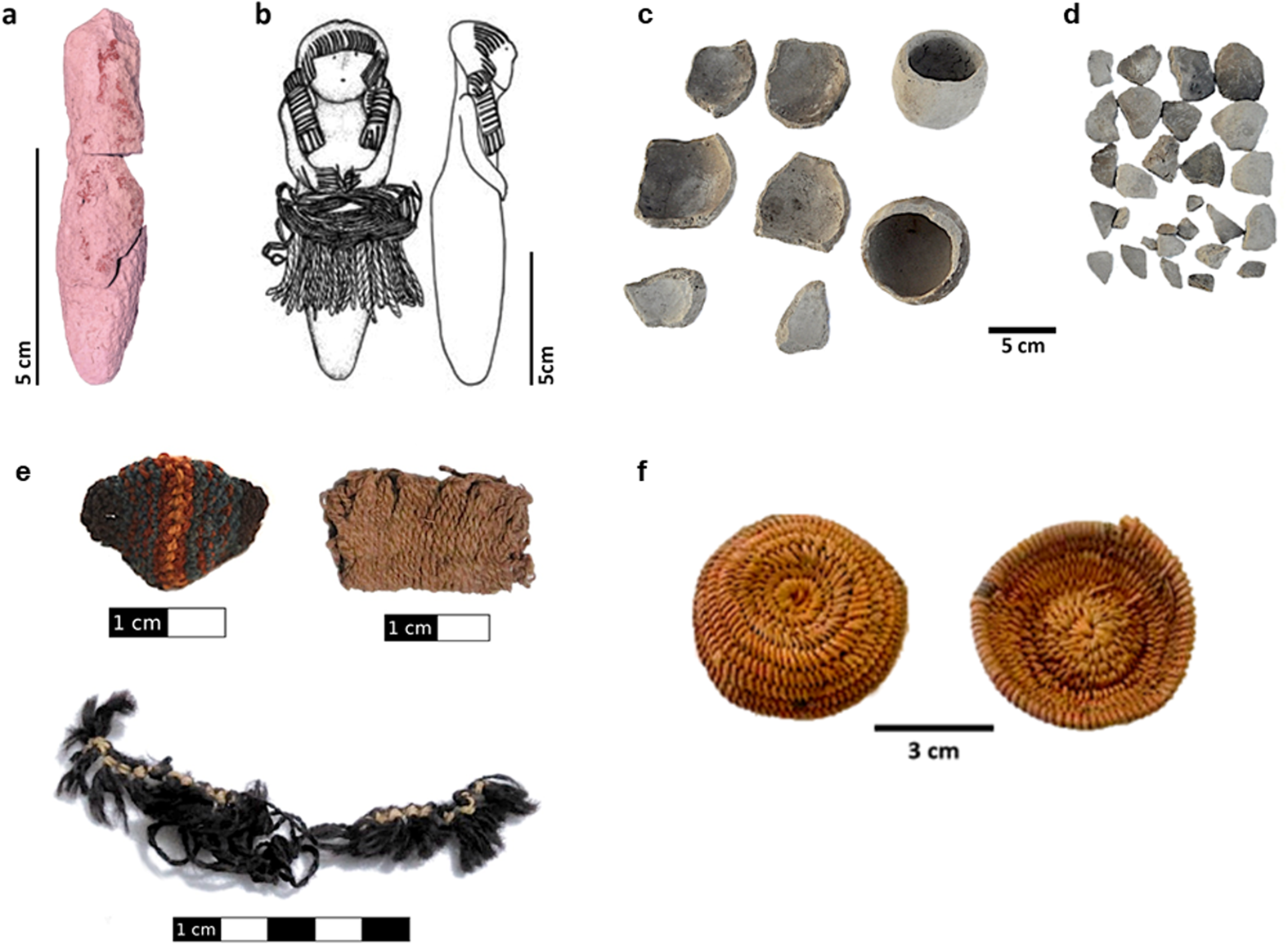

After her death, she was buried in the cemetery Tr-40, considered to be a necropolis that contains several generations, with individuals representing all ages (González-Ramírez et al. Reference González-Ramírez, Sáez, Herrera-Soto, Leyton, Miranda, Santana-Sagredo and Uribe-Rodríguez2021). Those who attended her funerary rite deposited different types of miniatures, such as pottery, an anthropomorphic figure, basketwork, and textiles, as well as maize cobs, next to her body (Figure 5). The presence of miniatures in Tr-40 is characteristic; they were popular offerings between about AD 200 and 600 (Figure 6; Núñez Reference Núñez1982; Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015). The miniatures reproduce objects of everyday life and are a representation of habitual socioeconomic practices of the Formative period (Uribe et al. Reference Uribe, Agüero, Catalán, Herrera and Santana-Sagredo2015). Moreover, these funeral offerings reflect the work of expert artisans and the specific knowledge of the Formative populations about the environment and its resources. Therefore, the woman's offerings may suggest a shared social life with the rest of the people buried in the cemetery. Likewise, the ceremonial act of burying her may reflect that she continued to be part of the community—only now from the space of the dead or ancestors who, of course, have agency in the world of the living (Urrutia and Uribe Reference Urrutia and Uribe2021).

Figure 5. Offerings from the section Y-tomb 1 (Tr-40), individual B2140: (a) ceramic anthropomorphic figurine; (b) representation of a ceramic anthropomorphic figurine associated with an infant burial, which is similar to the figurine buried with woman B2140 (illustration taken from Núñez [Reference Núñez2006] and used with permission of the author); (c) pottery vessel miniature; (d) pottery shards; (e) textile miniatures; (f) basket miniature.

Figure 6. Offerings from different tombs of cemetery Tr-40 dated to the Late Formative period: (a) fragment of a polychrome ringed cap, fragments of a tunic with diamonds designs on warp and weft, miniature tubular ringed bag, miniature overskirt, miniature basket, and zooarchaeological material; (b) basket section M’-tomb 41; (c) pumpkin type I with pyrographed decoration, section M’-tomb 88; (d) capacho type II.2 section K-tomb 4; (e) capacho miniature type I, section K-tomb 12; (f) miniature baskets, section K-tomb 11.

Based on the funeral treatment and the bioanthropological data, we propose that the woman was a member of the local group. We do so without falling into the antagonistic pairing of “local versus foreign” based only on the environment inhabited (e.g., coast vs. valley). Indeed, a person may have been born on the coast and died in the Pampa del Tamarugal, or vice versa, and still have been part of the same cosmology (Urrutia and Uribe Reference Urrutia and Uribe2021).

Sociopolitical Conditions of the Late Formative Period

The historical moment in which the woman of Tr-40 lived coincides with an increase in inequality and social complexity in the Tarapacá region and in other regions of the south-central Andes (Uribe and Adán Reference Uribe and Adán2012). Her death is considered an extreme expression and consequence of this historical context.

Physical violence in the Andes is strongly linked to communities with little political centralization (Arkush and Tung Reference Arkush and Tung2013). For the oases of San Pedro de Atacama, a high prevalence of antemortem trauma was recorded in females and males for the Middle period, which is contemporary with the Tarapacá Late Formative period (Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2004; Torres-Rouff et al. Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018). Torres-Rouff and colleagues (Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018) argue that nonlethal violence may have served as a means of providing structure for social norms and sanctions for their violation. In this sense, nonlethal violence can serve to reinforce social control among kin and others within a community (Martin and Harrod Reference Martin and Harrod2012; Torres-Rouff et al. Reference Torres-Rouff, Hubbe and Pestle2018).

This is consistent with the type of sociopolitical organization proposed for the Formative period in Tarapacá, which stipulated the biological, sexual, ideological, and economic norms to be adhered to by individuals (Uribe and Adán Reference Uribe and Adán2012). The organization of life was modulated also by the ancestors; it is not possible to understand this world if we separate the symbolic and ideational aspects from those of daily life. On the contrary, social life was constituted through entanglements with persons (humans, animals, ancestors), landscapes, everyday tasks, and festive practices in a way that transcends the Western spatiotemporal scale (Urrutia and Uribe Reference Urrutia and Uribe2021).

In this network, of course, there was room for social conflict. The times of crisis proposed for the final stage of the Formative in Tarapacá region—evidenced principally in the studies of Caserones-1 and the Tr-40 cemetery—probably are related to the development of excessive social control over individual actions (e.g., Adán et al. Reference Adán, Urbina, Uribe, Nielsen, Rivolta, Seldes, Vázquez and Mercolli2007; Agüero Reference Agüero2012; Herrera et al. Reference Herrera, Uribe, González-Ramírez, Sáez and Santana-Sagredo2019; Uribe Reference Uribe, Zarankin and Acuto2008). The settlement of Caserones was characterized by restrictions on access to the village and to the public spaces—known as plazas—that illustrate an intention to care for and control the walled public space (Adán et al. Reference Adán, Urbina, Uribe, Nielsen, Rivolta, Seldes, Vázquez and Mercolli2007). Caserones is proposed to be a symbolic space where social cohesion could be exercised through ceremonies and festivals; however, social control could also be used to reinforce collective coercion and discipline (Pellegrino et al. Reference Pellegrino, Adán and Urbina2016).

Architecture is not the only sphere that reflects restrictions, controls, and social inequality: bodies with evidence of violence also reflect a performative exercise of power (Foucault Reference Foucault2002). Hence, the death of a woman may make sense in her sociopolitical and historical network: power can generate effects on those who continue to live in the community (Pérez Reference Pérez, Martin, Harrod and Pérez2012). In consequence, any type of violence has the property of being collective or public, just as does power. That is why it is not possible to classify violence as domestic or ritual in character in archaeology or as any other category that makes its political role invisible. This savage killing entails an act of social violence—a moment of social tragedy—that was perhaps a signal of the new social forms that emerged at the end of the Formative (Uribe Reference Uribe, Zarankin and Acuto2008). This case is more evidence that the social development in the Formative did not necessarily imply social progress in relation to the hunter-gatherer tradition. Rather, it relates to a moment in which inequality and structural violence also developed and became evident during the Formative period.

The period known as Regional Development or the LIP (AD 900–1450) was characterized by other political dynamics and social conflicts. The representations of violence in Tarapacá during the LIP differ profoundly from those of the Formative period and of other contemporary regions (Arkush and Tung Reference Arkush and Tung2013; Nielsen Reference Nielsen2015), particularly in the low prevalence of physical violence and the presence in funeral contexts of objects associated with “warriors” (Pacheco and Retamal Reference Pacheco and Retamal2017). During the LIP in Tarapacá, violence goes beyond physicality, manifesting differently in the bodies, when the structural inequality and violence become institutionalized and symbolic elements are used as devices to maintain this new social panorama (Pérez Reference Pérez, Martin, Harrod and Pérez2012).

Conclusions

It is impossible to state with certainty who killed the woman of Tr-40 and why. What we can say is that none of the other individuals known from this cemetery experienced perimortem violence like she did. In other areas of the Atacama Desert, lesions derived from physical violence are generally interpreted as the result of “interpersonal conflict.” In the neighboring region of Arica, there is evidence of physical violence in Chinchorro populations from 10,000 to 1700 years BP (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Monsalve and Marquet2020, Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021). Explanations for the evidence of trauma in male bodies usually refer to competition for resources and territories, attacks by foreigners (coast versus valley) or sporadic intragroup struggles (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Arriaza, Santoro, Romero and Rothhammer2010, Reference Standen, Arriaza, Santoro, Romero and Rothhammer2020). When women show trauma related to violence, it is emphasized that the frequency is low in relation to men, and the explanations center on “domestic violence” without further details (Standen et al. Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Monsalve and Marquet2020, Reference Standen, Santoro, Bernardo Arriaza, Susana Monsalve, Valenzuela and Marquet2021).

In contrast, violence in San Pedro de Atacama is usually attributed to ritual battles related to the practice of Tinku (e.g., Lessa and Mendonça de Souza Reference Lessa and de Souza2007) or to conflicts stemming from ecological stress and foreign contacts (e.g., Torres-Rouff and Costa-Junqueira Reference Torres-Rouff and Costa-Junqueira2006). This limited repertoire of causes to explain physical violence reflects the absence of an explicit social theory about conflict and, in particular, an insufficient treatment of the participation of women in social conflicts.

The microhistory of the woman of Tr-40 is not at odds with the sociopolitical and historical context of the Late Formative period in northern Chile. Her osteobiography allows us to better understand a society affected by internal contradictions. We view this violent death as an extreme manifestation of the complexity and social inequality of the Late Formative period in the Atacama Desert. Understanding that in every society complexity and inequality are manifested in engendered bodies, either through physical punishment or through the social customs of quotidian life that support compliance with social norms, we view this death as an example of how power operates. In women and other marginalized identities, this power is exercised through corrective and violent sanctions that are historical and socially normalized and the embodiment of duties that shape their social behavior and identities according to societal expectations (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1997; Butler Reference Butler2002; Foucault Reference Foucault2002).

Therefore, we reject the use of such categories as domestic, private, or intrafamily to describe violence against female bodies in ancient societies. First, violence in any of its manifestations transcends all spheres of life. Second, these categorizations are characteristic of Western and patriarchal ontologies, denying the possibility that women may have played central roles associated with social, economic, and political affairs (García-Peña Reference García-Peña2016; Millet Reference Millet2010; Vila-Mitjà Reference Vila-Mitjà2011). Instead, we propose an alternative interpretation for an Andean woman's death based on her social body and historical context.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for comments that greatly improved this article. We thank Universidad Arturo Prat and Universidad de Chile for permitting the publication of data obtained from the analysis of funerary objects and human remains.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Chilean FONDECYT project grant #1181829. Herrera-Soto received a grant from Becas Chile, Asociación Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID).

Data Availability Statement

The 3D reconstruction of the cranial is in the dataset specified in Herrera (Reference Herrera2020). Further details can be obtained from the authors.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/laq.2022.92.

Supplemental Table 1. Bioanthropological Record of Individual B2140.

Supplemental Table 2. Cranial Vault Traumas of Individual B2140.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flattened morphology of the left mandibular condyle with signs of pitting and lipping.

Supplemental Figure 2. Dental record of individual B2140. The numbers inside the teeth indicate the degree of occlusal wear, according to Smith (1984) and Scott (1979). Absence of caries and periapical lesions in both arcades.

Supplemental Figure 3. Groove in upper left second molar (black arrow).

Supplemental Figure 4. Left posterolateral view of the cranial vault: (a) impact points (white arrows) produced by the first, second, and third blows; (b) detail of the lesions produced by the first and the second blows; (c) endocranial view of left parietal; (d) detail of inner table with lesions 1 and 2.