Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 November 2014

1 Tholbecq, L., “Le haut-lieu du Jabal Numayr (Pétra, Jordanie),” Syria 88 (2011) 301–21CrossRefGoogle Scholar; id., “Infrastructures et pratiques religieuses nabatéennes: quelques données provenant du sanctuaire tribal de la ‘Chapelle d’Obodas’ à Pétra,” in F. Alpi, V. Rondot and F. Villeneuve (edd.), La pioche et la plume. Autour du Soudan, du Liban et de la Jordanie. Hommages archéologiques à Patrice Lenoble (Paris 2011) 31-44.

2 For a historiography of high places, see Bonnet, C., “Entre terre et ciel. Parcours historiographique en ‘hauts-lieux’ sur les traces de Franz Cumont et d’autres historiens des religions,” Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 7 (2005) 5–19 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

3 E.g, still very recently, Ma‘oz, Z. U., Mountaintop sanctuaries at Petra (Qazrin 2008)Google Scholar.

4 Musil, A., Arabia Petraea. II. Edom, topographische Reisebericht (Vienna 1907) 124 Google Scholar.

5 The expedition, which left Cairo in 1882, brought together the Reverend Douglass (sic) P. Birnie, William B. Ogden and photographers William H. Rau and Edward L. Wilson, both of whom enjoyed exceptional careers. For Forder's discovery see Robinson, G. L., “The high-places of Petra,” Biblical World 31.1 (1908) 8–21 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

6 Wilson, E. L., “A photographer's visit to Petra,” The Century Magazine 31.1 (1885) 19–24 Google Scholar.

7 Ogden, W. B., “Four days in Petra,” J. Am. Geog. Soc. New York 20.2 (1888) 150–51Google Scholar.

8 Robinson, G. L., “The newly discovered high place at Petra in Edom,” Biblical World 17.1 (1901) 6–16 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Curtiss, S. I., “High place and altar at Petra,” PEFQS Oct. 1900, 350–55Google Scholar.

9 Brünnow, R. E. and Domaszewski, A. von, Die Provincia Arabia, 1. Die Römerstrasse von Mâdebâ über Petra und Odruh bis el-Akaba (Strasburg 1904) 239–45Google Scholar.

10 Libbey, W. and Hoskins, F. E., The Jordan Valley and Petra (New York 1905)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

11 Hoskins, F. E., “A third “High-Place” at Petra,” Biblical World 27.5 (1906) 385–90CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12 Molloy, V. and Colunga, A., “Lieux de culte à Pétra. Le haut-lieu d’el-Hubzeh,” RBibl 3 (1906) 586–87Google Scholar.

13 Robinson (supra n.5) 8.

14 Dalman, G., Petra und seine Felsheiligtümer (Leipzig 1908)Google Scholar.

15 Dalman, G., Neue Petra-Forschungen und der Heilige Felsen von Jerusalem (Leipzig 1912)Google Scholar.

16 Dalman (supra n.14) 329-44; Nehmé, L., “L’espace cultuel de Pétra à l’époque nabatéenne,” Topoi 7.2 (1997) 1035–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Ma‘oz (supra n.3); Alpass, P., The religious life of Nabataea (Leiden 2013) 71 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

17 M. Lindner, “Neue Erkundung des Dschebel el-Hubta,” in id. (ed.), Petra. Neue Ausgrabungen und Entdeckungen (München 1986) 130-37.

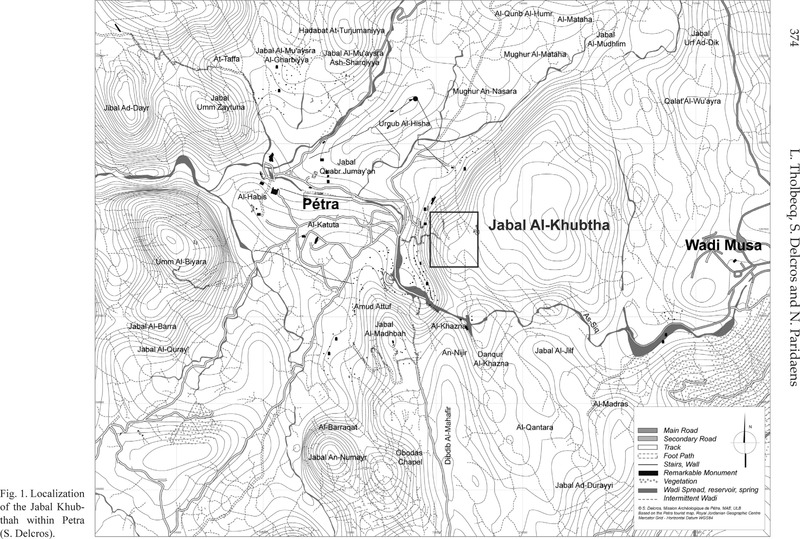

18 Lindner, M. et al., “An Iron Age (Edomite) occupation of Jabal al-Khubta (Petra) and other discoveries on the ‘Mountain of Treachery and Deceit’,” ADAJ 41 (1997) 177–88Google Scholar; id., “Götterberg über Königsgräbern, Heilig und ‘Hinterlistig’: der Jebel el-Khubtha,” in id. (ed.), Über Petra hinaus. Archäologische Erkundungen im südlichen Jordanien (Rahden 2003) 116.

19 Nehmé, L., Atlas archéologique et épigraphique de Pétra, fasc. 1 (Paris 2012) 228–30Google Scholar.

20 Schmid, S. et al., “The palaces of the Nabataean kings at Petra,” in Nehmé, L. and Wadeson, L. (edd.), The Nabataeans in focus: current archaeological research at Petra (Oxford 2012) 85–93 Google Scholar.

21 Numbers preceded by a D refer to the inventory of Dalman (supra n.14).

22 Dalman (supra n.14); Nehmé (supra n.19) map 2.

23 Dalman (supra n.14) 332-34.

24 Starcky, J., Dict. Bible, Suppl. 7 (1966) col. 1006Google Scholar.

25 With the possible exception of the small temple of Qasrawât (Sinaï), which seems to be of a properly Egyptian tradition: Oren, E., “Excavations at Qasrawet in north-western Sinaï, preliminary report,” IEJ 32.4 (1982) 203–11Google Scholar.

26 Dalman (supra n.14) 335; Wenning, R., “Einneuer Augenbetyl aus Petra,” Jb. Deutsches Evang. Inst. f. Altertumswissenschaft des Heiligen Landes 11 (2009) 119 Google Scholar; Tholbecq, Syria 2011 (supra n.1) 316; Nehmé (supra n.19) 121; Alpass (supra n.16) 71.

27 Dalman (supra n.14) 336-37, fig. 305; id. (supra n.15) 38-39.

28 Tholbecq, L., “Archaeology in Jordan,” AJA 116 (2012) 736–37, fig. 21Google Scholar.

29 Ibid. 736-37. For this last structure, see Schmid, S. G., “Überlegungen zum Grundriss und zum Funktioneren nabatäischer Grabkomplexe in Petra,” ZDPV 125 (2009) 158–59Google Scholar.

30 Tholbecq, La pioche et la plume (supra n.1).

31 Dalman (supra n.14) 338-39.

32 Nehmé (supra n.19) 122.

33 Mouton, M., “Les plus anciens monuments funéraires de Pétra: une tradition de l'Arabie préislamique,” Topoi 14 (2006) 79–119 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Tholbecq, L., “Nabataean monumental architecture,” in Politis, K. (ed.), The world of the Nabataeans. Int. Conf. ‘The World of the Herods and the Nabataeans’, vol. 2 (Stuttgart 2007) 106–10Google Scholar; Mouton, M. and Renel, F., “The early Petra monolithic funerary blocks at Râs Sulaymân and Bâb as-Sîq,” in Mouton, M. and Schmid, S. (edd.), Men on the rocks: the formation of Nabataean Petra (Berlin 2013) 135–62Google Scholar.

34 Lenoble, P., al-Muheisen, Z. and Villeneuve, F., “Fouilles de Khirbet edh-Dharih (Jordanie), I: le cimetière au sud du Wadi Sharheh,” Syria 78 (2001) 100–6CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Talal Amareen (Dept. of Antiquities, Wadi Musa) has seen others in the areas surrounding the city centre. A systematic study should be undertaken.

35 Information from L. Wadeson and F. Abudanah.

36 Dalman (supra n.14) 336; Nehmé (supra n.19) n° 1768.1.

37 Lindner 2003 (supra n.18) 116.

38 Site Khh4, Nehmé (supra n.19) 146; Lindner ibid. 119, fig. 13.

39 Nehmé (supra n.19). We will return elsewhere to the circular platform, which adjoins the motab of the Madhbah and has probably been wrongly interpreted as a sacrificial space; perhaps it is simply a banqueting space, in the spirit of a stibadium.

40 Z. T. Fiema, “The FJHP site,” in id. and J. Frösen (edd.), Petra – The Mountain of Aaron. The Finnish Archaeological Project in Jordan, vol. I. The church and the chapel (Helsinki 2008) 86-97; id., “Reinventing the sacred: from shrine to monastery at Jabal Harûn,” in L. Nehmé and L. Wadeson (edd.), The Nabataeans in focus: current archaeological research at Petra (Oxford 2012) 27-37.

41 Tholbecq, Syria 88 (2011) (supra n.1).

42 McKenzie, J., Greene, J. A. and Reyes, A. T., The Nabataean Temple at Khirbet Et-Tannur, Jordan: final report on Nelson Glueck's 1937 excavation (Boston, MA 2013)Google Scholar.

43 Information from C. Durand, publication forthcoming.

44 Nehmé (supra n.19) carte 2, cheminement 1758.

45 Wenning (supra n.26).

46 Nehmé (supra n.19) 218-20.

47 Nehmé, L. et al., “Mission archéologique de Madā' ịn Ṣāliḥ (Arabie Saoudite): recherches menées de 2001 à 2003 dans l’ancienne Hijrâ des Nabatéens,” Arabian Arch & Epig. 17 (2006) 91–96 Google Scholar.

48 Nehmé, L., al-Talhi, D. and Villeneuve, F., “Résultats préliminaires de la première campagne de fouilles à Madā' ịn Ṣāliḥ en Arabie Saoudite,” CRAI 2008, 662–67Google Scholar.

49 Bedal, L.-A., The Petra pool-complex: a Hellenistic paradeisos in the Nabataean capital (Piscataway, NJ 2003)Google Scholar; S. Schmid et al., “The palaces of the Nabataean kings at Petra,” in Nehmé and Wadeson (supra n.40) 85-93.

50 Schmid, S. and Bienkowski, P., “Eine nabatäische Königsresidenz auf Umm al-Biyara in Petra,” in Petra, Wunder in der Wüste. Auf den Spuren von J. L. Burckhardt alias Scheikh Ibrahim (exh. cat., Basel 2012) 252–61Google Scholar; Schmid et al. (supra n.49) 75-85; one could also refer to the spectacular Nabataean banqueting-hall linked to a bath complex at Beidha, a northern suburb of Petra: Bikai, P. M., Kanellopoulos, C. and Saunders, S. L., “Beidha in Jordan: a Dionysian hall in a Nabataean landscape,” AJA 112 (2008) 465–507 CrossRefGoogle Scholar.