The southern island of Mindanao in the Philippines has been the politico-military arena of a longstanding territorial conflict (Bertrand, Reference Bertrand2000; Buendia, Reference Buendia2005) often described as a Muslim–Christian clash (Milligan, Reference Milligan2001; Tan, Reference Tan2000). However, Mindanao is not only the Philippine hotbed of territorial conflict, it is also a region in which several peace initiatives have taken place. During the Marcos regime, and especially after the People Power Revolution in 1986 ushered in a new democracy, different Philippine presidents have attempted to establish peace in Mindanao. In 2008, a peace agreement called the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) was signed by the peace panels of the Philippine government and the Moro International Liberation Front (MILF).

The MOA acknowledged two basic rights of the Moro people — identity and land. The peace agreement asserted the birthright of all Moros and indigenous peoples of Mindanao to claim their identities as Bangsamoros, delineated territorial boundaries that belonged to the Bangsamoro, and created the Bangsamoro Juridical Entity to hold authority over these defined territories. The public announcement of the MOA triggered a series of peaceful and armed protests among Christians, and counter-protests among Moro-associated forces. The Supreme Court eventually junked the peace agreement, and the Philippine president fired the government peace panel that she herself had constituted.

This recent peace fiasco likewise called attention to divisions among Muslims. With this recent unsuccessful attempt to establish peace in Mindanao, we investigated the nature of the psychological fractures within the Muslim front. We looked at how different Islamised groups in Mindanao made sense of the Memorandum of Agreement. However, as social psychologists who are Christians, we reflexively acknowledge our perceptive limitations as we attempted to understand political meanings held by two different Islamised tribes in what has been labelled a Muslim–Christian conflict. We viewed our research question through the lens of social representations theory, because this theory lends itself well to illuminating the subjective landscape of social conflict.

Social Representations Theory

Social representations refer to shared knowledge about a social object. Such shared knowledge is socially constructed by group members who interact with each other (Moscovici, Reference Moscovici1988). Social representations become powerful psychological realities in the public minds of members of a social group, and fuel collective group behaviour (Montiel, Reference Montiel2010). Social representations turn particularly dynamic when something new and unknown is introduced to a group, and as the group makes sense of this social novelty (Sarrica & Contarello, Reference Sarrica and Contarello2004). In our study, this novel social concept was the Memorandum of Agreement for peace in Mindanao.

Social representations theory further identifies two group-based psychological processes involved in collective meaning-making, the processes of objectification and anchoring (Philogene & Deaux, Reference Philogene, Deaux, Deaux and Philogene2001). Objectification is concerned with transforming the abstract, in this case the peace agreement, into something concrete. Readily available information are selected and simplified (Abric, Reference Abric1996). On the other hand, anchoring is the process of integrating this new information within a system of familiar categories. People attach labels (e.g., Muslim–Christian conflict) to the unfamiliar phenomenon (peace agreement), making possible the absorption of new information to an old setting which generates a system of interpretation and offers a framework for determining behaviour.

We posit that the Mindanao conflict was historically anchored on religious categories owing largely to political labelling by Spanish and American colonisers. The following section explains how the label ‘Muslim–Christian conflict’ evolved from a history of Mindanao marked by Christian foreign intrusions and Muslim resistance. We then discuss the ethnic contours of Islamised tribes and link this to divided social representational anchorings of a territorial peace agreement. We further argue that during peace talks, social representations of territorial agreements are anchored not only along religious lines, but also along ethnic contours among the nonmigrant land-attached groups.

Historical Anchoring: Using Religious Labels to Make Sense About Subverting Muslim-populated Mindanao

Islam reached Mindanao sometime in the 10th century or at the latest by the 14th century, through Arab traders going to China from the Arabian Peninsula (Frake, Reference Frake1998; Majul, Reference Majul1973). The Arabian traders travelled through Malaysia, Mindanao, and other parts of the Philippine archipelago, to reach China. Islam entered and settled in Mindanao without any invasion or conquest involved among the local people of Mindanao (Frake, Reference Frake1998).

The first religious label in the context of armed conflict emerged in the 16th century when the Spanish colonial forces repeatedly and unsuccessfully attempted to conquer the island of Mindanao which was, at that time, largely populated by Islamised tribes. The 16th century Spanish colonisers called the local Mindanao population Moro, the same name the Spaniards used for their Muslim enemies in Spain, the Moors (Frake, Reference Frake1998). However, the Islamised tribes did not call themselves Moros during the Spanish times. Note that the label Moro was a religious category connoting outstanding fierceness during combat. By the close of the 19th century, Spain ceded the Philippine Islands to America. During America's control over the Philippines in the first half of the 20th century, religious categories were again used in Mindanao, but the narrative shifted from military positioning by the Spaniards to economic positioning under American control. Mindanao Christians were largely favoured to own bigger tracts of land, through a law that structured the distribution of public land in Mindanao.

The Public Land Act or the Commonwealth Act 141 of 1936 used the religious labels ‘Christians’ and ‘non-Christians’. The Public Land Act allowed a Christian to buy a maximum of 144 hectares of land while a non-Christian could only acquire not more than four hectares (Montiel, de Guzman, Inzon, & Batistiana, 2010). Hence under America's colonial influence, economic dispossession of Muslim Mindanaoans was implemented through the religious label of ‘non-Christian’.

The above examples demonstrate how the Muslim–Christian religious anchoring was evoked in colonial narratives of conflict in Mindanao. However, these religious categorisations were not initiated by Muslims in Mindanao, but by Christian Spaniards, Americans, and their Filipino allies, in attempts to conquer Islamised tribes in Mindanao through military and economic strategies.

Only in the recent past have the Mindanao Muslims claimed the label ‘Moro’ for themselves (Frake, Reference Frake1998). They have done so in the context of their politico-military territorial struggle in Mindanao against the Christian-dominated Republic of the Philippines. When the Mindanao war exploded in the early 1970s, the organisation that spearheaded the struggle for territorial rights against the Philippine government was the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). By the 1980s a second politico-military group for territorial independence/autonomy in Mindanao likewise turned more politically visible, under the banner Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF). Both the MNLF and MILF have reclaimed the name ‘Moro’, reviving the image of fierce fighters for independence against foreign intruders.

Both liberation groups say that they are fighting for an independent/autonomous Bangsamoro or Moro Nation. Hence, the marginalised groups evoke a religious anchoring in the conversation about the Mindanao conflict. Their battle cry is a religious one, and is defined by the use of Moro in the names of the two primary liberation groups in Mindanao, and also by the expressed goal of both organisations which is the attainment of the Bangsamoro or the Moro nation. Even as the public discourse now moves from conflict to peacemaking, the same religious categories of war continue to be evoked in the Mindanao peace agreement. This is illustrated in the language used in the peace agreement (i.e., Memorandum of Agreement or MOA) to resolve territorial contentions in Mindanao. The MOA document explicitly recognises ‘the birthright of all Moros and all Indigenous peoples of Mindanao to identify themselves and be accepted as Bangsamoros’. This call for Bangsamoro identity and homeland once more signifies a religious labeling. We ask however, if pragmatic peacemaking and talks about land sharing evoke ethnopolitical anchoring in addition to religious Muslim–Christian anchoring.

Fragmented Social Representations of a Territorial Peace Agreement Among the Nonmigrant Groups

Ethnopolitical groups define themselves by some combination of common ancestry, shared history, language, and valued cultural traits (Gurr & Moore, Reference Gurr and Moore1997). Individuals who share a common descent and set of ancestors tend to share proximal space. Because ethnic groups live within defined territorial boundaries (Chandra, Reference Chandra2006), territorial conflict and peacebuilding efforts need to consider ethnopolitical faultlines as well (Harnischfeger, Reference Harnischfeger2004). We predicted that such ethnopolitical contours existed not only as demographic and historical facts, but also as psychological spaces of fragmented subjective landscapes as well.

In the context of the Mindanao territorial conflict, territory is closely associated with ethnopolitical groups (Buendia, Reference Buendia2005). Tribal groups in Mindanao were present even before the arrival of Islam in Mindanao. At around the time Islam arrived in Mindanao through commercial traders, two dominant yet territorially distanced tribes had risen to politico-economic superiority and had formed two sultanates. These were the Tausugs in Jolo (Southwestern Mindanao) and the Maguindanao/Maranao tribes in Central Mindanao (Frake, Reference Frake1998). Both Tausugs and Maguindanaoans/Maranaos lived in ethnic societies glued together by tribal loyalties, languages, kinship ties, and territorial spaces defined even before the coming of Islam. Maguindanaoans and Maranaos live closer to each other, interact more often, and are friendlier to each other than to the Tausugs. Henceforth, for parsimonious reading, we refer to the Maguindanao/Maranao ethnic groups as the Maguindanaoans.

Although both Islamised tribes had historically spearheaded resistance movements against Christian colonial and domestic forces, both Tausugs and Maguindanaoans remained relatively unaware of the Other Islamised tribe. Both ethnic groups did not relate with each other frequently, because they were spatially separated and the defence of their lands only required local rather than Mindanao-wide efforts. They could not communicate with each other because they did not share a common language. They possessed two distinct tribal languages, with each language incomprehensible to the other tribe (Frake, Reference Frake1998).

After the 1960s, the term Moro was claimed by the liberation movements among the Islamised tribes. The leading ethnic groups formed two distinct politico-military organisations, with the Tausugs consolidating under the banner of the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF), and the Maguindanaoans rallying under the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) (Bertrand, Reference Bertrand2000; Buendia, Reference Buendia2005; Frake, Reference Frake1998). Bangsamoro (Moro nation) became a battle cry for the various Muslim liberation groups. But the singular call for a Bangsamoro did not reflect operational unity between the MNLF and the MILF.

The term Moro was used primarily as a linguistic tool to distinguish Islamised tribes from the Christian world. The religious label bound Muslim Mindanaoans only when they engaged in macro political conversations with Christians. As Kreuzer (Reference Kreuzer2005) emphasised, ‘Bangsamoro . . . unifies the various Moro groups only to a small degree. It is relevant politically in order to be heard by the Philippine government or the international donor community . . . In terms of content, the bands are weak, the Muslims see themselves as members of their clans and ethnic group, and only secondary as Muslims’ (p. 22). Thus, even if the nonmigrant group, the Muslims, claimed Bangsamoro, they remained ethnopolitically fragmented.

As a peace process emerges out of the rubble of a centuries-old conflict between Christians and Muslims, the peace narrative needs to address issues of territorial dominion. Interestingly, the central linguistic tool for peace talks fuses territory and ethnicity. The term ‘ancestral domain’ was the most contentious topic during the 2008 failed peace talks between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Note that the label ‘ancestral domain’ describes control over territory (domain) that is associated with ethnic descent (ancestral).

As talk about the Memorandum of Agreement arises in the public sphere of conflicted Mindanao, how do different Mindanao groups make sense of this novel social object? Would representational anchorings about the peace agreement reflect the religious divide of a so-called Muslim–Christian conflict? A deeper question then arises about whether two nonmigrant and physically separated Islamised tribes can share a common understanding about one peace agreement. This question becomes crucial because bilateral peace talks assume that shared knowledge about a peace memorandum would be divided between Christians and Muslims, but unified within each of these groups.

Moscovici (Reference Moscovici1988) identified three ways by which representations interface with intergroup relations. Hegemonic representations are shared by all members of a society and appear to be uniform. Emancipated representations can be observed when social groups share similar representations, but highlight different aspects of these representations. Polemic representations, on the other hand, are antagonistic and arise during social conflict. These representations are evoked during social controversy and provide the subjective landscape of intergroup conflicts (Montiel & de Guzman, 2011). They tend to be contradictory and contested, as members of different social groups dispute the social meanings of a particular social object.

We predicted polemic representational anchoring about the Memorandum of Agreement, not only across the religious divide but also among the Islamised tribes. We expected polemic social representations of the peace agreement only among the nonmigrant Islamised groups rather than the Christian settler group, because the former carry tribal loyalties beyond an Islamic religion, and are attached to the contested territory. In territorial conflicts, ethnopolitical anchoring may be evoked more passionately by groups who have had centuries-old attachments to the contested land, rather than by the migrant or settler groups. Hence we did not expect any fractures in the social representations of the peace agreement among Christians.

Ethnopolitical Social Representation of a Peace Agreement: Two Studies

We ran two studies that asked the questions: Do social representations about the Memorandum of Agreement divide along the tribal faultlines of the Islamised groups? On the other hand, are social representations about the peace agreement homogeneous among Christians?

Study One surveyed college students and staff in selected territories of Mindanao associated with the Tausug and Maguindanao Islamised tribes. This study compared social representations of the peace agreement across religion and territory. According to Abric (Reference Abric1996, 2001), social representations have a stable central element called the central core, and more peripheral changeable elements. The central core is the main element because it determines the structure of the representation and verifies the relevance of the representation as whole. We used Abric's (2008) hierarchical evocation method to provide representational structures and identify central cores. Each group's representational central core was described, to find out if central cores about the peace agreement varied across groups.

Study Two used media analysis to identify social representations (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Duveen, Farr, Jovchelovitch, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Markova and Rose1999) about the peace agreement. In the second study, we collected and analysed public utterances about the contested peace agreement by two ethnically identified Muslim liberation organisations, the Maguindanaoan-dominated Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the Tausug-led Moro National Liberation Front (Betrand, 2000; Buendia, Reference Buendia2005; Frake, Reference Frake1998). Study Two presents competing public storylines about the Memorandum of Agreement, as advanced by these two ethnically-different Muslim resistance groups.

Study One: Structure of the Social Representations of the Memorandum of Agreement Across Religious and Territorial Groups

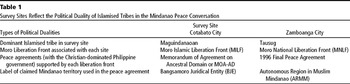

We ran our survey in two research sites with distinct Islamised populations: (1) Cotabato City, which is populated by the Muslim Maguindanaoan group; and (2) Zamboanga City, wherein Tausugs are the dominant Islamised tribe (National Statistics Office, 2002). We note at this point that the Maguindanaoans exert influence in the MILF whereas the Tausugs are known to be in control of the MNLF. Table 1 summarises the ethnopolitical duality of these two research sites, the Islamised tribes within these territories, and their alignments in Muslim liberation groups.

Table 1 Survey Sites Reflect the Political Duality of Islamised Tribes in the Mindanao Peace Conversation

Our sampling design consisted of a 2 × 2 matrix, with participants categorised according to religion (Christian or Muslim) and territory (Cotabato or Zamboanga). We surveyed 420 participants from the Notre Dame University in Cotabato City (n = 193) and the Ateneo de Zamboanga University in Zamboanga City (n = 227). Both sampled universities were highly recognised private schools in their respective territories, and had produced regional leaders from their respective academic institutions. The Cotabato student sample consisted of 94 Christians and 99 Muslims. The Zamboanga sample had both students and staff respondents, with 144 Christians and 83 Muslims. Data collection did not pose any problem in both sample sites because we had personal contacts in both academic institutions. Further, at the time of data collection, the first author was a visiting professor at the Ateneo de Zamboanga University.

Survey Instrument and Data Analysis

The survey explored local people's social representations of the 2008 peace agreement. We asked participants to mark their position in relation to the following statements: (a) I am for the signing of the MOA (Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain), (b) I am not for the signing of the MOA, and (c) Others, please describe. We then computed for the percentage of participants who indicated their support for the signing of the MOA, across religious and territorial groups.

We also utilised a free word association task to investigate how participants socially represented the peace agreement. In this task, we asked participants to imagine themselves conducting a lecture about the peace accord. We then asked them to state the three most important features of the agreement that they would include in their lecture. We adopted a structural approach in analysing the data from the free word association task.

The structure of social representations may be studied through a quantitative method known as the hierarchical evocation method (HEM; Abric, Reference Abric2008; Wachelke, Reference Wachelke2008). Among other things, HEM identifies the central core of a social representation. The central core consists of the main elements of a social representation; it is ‘stable, coherent, consensual, and considerably influenced by the group collective memory and its system of values’ (Abric, Reference Abric1996, p. 79).

Operationally, HEM identifies the central core of a social representation by examining two criteria — the frequency and the order of evocation of a representational element. Thus, central core elements refer to the responses that are mentioned more frequently (high frequency) and more immediately (low average evocation order) (Abric, Reference Abric2008; Roland-Levy & Berjot, 2009; Wachelke, Reference Wachelke2008; Wolter, Gurrieri & Sorribas, 2009).

Our data analysis using the hierarchical evocation method followed a two-stage process. First, we examined the responses to the free word association task using thematic analysis, a method that allowed us to identify meaningful patterns in the data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Because our aim was to identify central core elements — defined as those themes with high frequency and low evocation order, we excluded some themes that had significantly low frequencies (less than 5% of total responses; J. Wachelke, personal communication, May 7, 2012).

We then computed for the average frequency and the average evocation order of each theme. Because of the unequal group sizes, we utilised the percentage of occurrence of each theme. Readers may refer to Abric (Reference Abric2008) and Wachelke (Reference Wachelke2008) for more procedural details about the use of the hierarchical evocation method in social representations research.

Results: Christian Hegemony and Muslim Fragmentation in the Social Representations of the Memorandum of Agreement

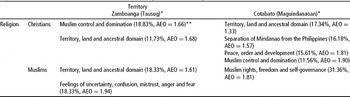

Our findings show Christian hegemony and Muslim fragmentation in the social representations of the 2008 peace agreement. Figure 1 illustrates the patterns of support for the peace agreement across religions and territories. Our results showed that Christian participants from both locations opposed the peace accord. Table 2 presents the representational elements of the central core across religious and territorial groups. Specifically, our findings showed that some of the central core elements of the Christian representation of the MOA were shared across territories while other elements appeared to be unique only to Christian participants from one territory.

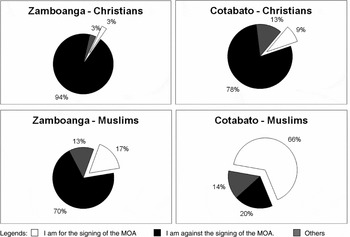

Table 2 Representational Central-Core Elements of the Memorandum of Agreement, Across Religions and Territories

*Note: * The terms within parentheses refer to the name of the Islamised tribes in these particular territories.

** The percentages refer to the frequency of occurrence of each theme. AEO stands for the average evocation order or the average rank of each theme, where 1 = most immediately evoked and 3 = less immediately evoked.

Figure 1 Public support/opposition to the Memorandum of Agreement across religious and territorial groups.

In particular, Christian participants from Cotabato and Zamboanga made sense of the peace agreement in relation to the following central core elements: (1) Muslim control and domination in Mindanao, and (2) issues about territory, land, and ancestral domain. However, it is important to note that the central core of the social representations held by Cotabato Christians included other elements, such as the meanings of the peace agreement in relation to peace, order, and development in Mindanao, as well as issues related to the separation of Mindanao from the Philippines. This indicates that although Christian groups from Cotabato and Zamboanga held hegemonic representations about the peace agreement, Christian participants from the former site may have a more complex representation about this particular social object.

More importantly, our findings revealed ethnopolitical fragmentation between the two Muslim groups in relation to the 2008 peace agreement. The majority of Tausug Muslim respondents opposed the peace accord. Interestingly, this Islamised group's social representations stood closer to those held by the Christian groups. Among the Tausugs, the social meanings of the said peace accord were linked to (1) issues about land, territory, and ancestral domain, and (2) feelings of uncertainty, confusion, mistrust, anger, and fear. In contrast, the majority of Maguindanaoan Muslims supported the peace agreement. Maguindanaoans socially represented the Memorandum of Agreement as linked to Muslim rights, freedom, and self-governance. The representational fracture between Islamised tribes shows Tausug Muslims emphasising negative emotions, and Maguindanaoan Muslims explaining the peace agreement in a positive light. Table 3 lists down the themes that comprised the representational core elements of each subgroup along with sample responses that comprise each particular theme.

Table 3 Sample Responses per Theme Generated From the Free Evocation Task About the Memorandum of Agreement

Study Two: Public Meanings of the Memorandum of Agreement According to Two Ethnically-Different Muslim Liberation Movements

Study One showed that Muslim participants from two different territories held fragmented representations about the 2008 peace agreement. Building on this finding, we further investigated the social meanings of this peace agreement according to two ethnically different Muslim liberation movements — the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). Social representations can also be studied by looking at the discourses that different social groups hold about a particular social object (Wagner et al., Reference Wagner, Duveen, Farr, Jovchelovitch, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Markova and Rose1999).

To investigate the social representations of the 2008 peace agreement according to these two ethnopolitical groups, we gathered news articles and accounts regarding this social object from the following sources: (1) the internet version of the Philippine Daily Inquirer, the nation's most widely circulated newspaper, and (2) the official website of the MILF Central Committee on Information. We collected data that were published from July 2008 to April 2009, corresponding to the period when information about the peace accord first emerged in the public sphere up to the period when the contentions about the agreement started to subside. Through this process, we accumulated 169 articles and accounts. Most of the articles about the MOA involved the MILF, mainly because this liberation movement was the main proponent of this peace agreement. Nevertheless, our dataset also included some key accounts highlighting the position of the MNLF in relation to the controversial peace accord. We then extracted statements and arguments about the peace agreement that were issued by the MILF and the MNLF. Finally, we read and re-read these key utterances to identify the social meanings that these two ethnopolitical groups ascribed to this particular peace accord.

Results: MILF-MNLF Polemical Representations about the Memorandum of Agreement

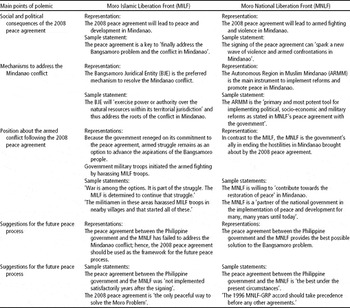

Our findings showed that the two Muslim ethnopolitical groups — the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) — held polemic representations about the 2008 peace agreement. The social representations of the said peace accord varied between these two groups in terms of four main points: (1) the social and political consequences of the peace agreement, (2) the mechanism that each group proposed to address the Mindanao conflict, (3) the positions that each group took in relation to the armed conflict that followed the controversy over the peace agreement, and (4) each group's suggestions on how to move the peace process forward. Table 4 shows the polemical themes that emerged from the collected utterances of these two ethnopolitical groups, along with sample statements from each group.

Table 4 Ethnopolitical Fragmentation Between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF)

As the main proponent of the agreement, the MILF argued that the peace accord would lead to peace and development in the Mindanao region. In contrast, the MNLF cautioned that the agreement would precede armed fighting and violence in Mindanao. Polemic representations of the peace agreement were also observed in relation to the mechanisms that each group proposed to address the conflict in Mindanao. On the one hand, the MILF-sponsored peace agreement recommended the creation of Bangsamoro Juridical Entities to enable the Bangsamoro people to exercise governance over their ancestral domain and thus provide a solution to the conflict in the region. On the other hand, the MNLF reiterated the role of the existing Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) as the primary mechanism to implement the necessary reforms to promote peace in Mindanao. In addition, the MNLF also strongly opposed the inclusion of ARMM provinces in the territories claimed by the MILF in the Memorandum of Agreement.

A third point of divergence between the MILF and the MNLF involved the position that each ethnopolitical group took in relation to the armed fighting that erupted during the social controversy about the 2008 peace agreement. For the MILF, armed struggle remained to be one of the options to advance the aspirations of the Bangsamoro people. The MILF also argued that their field commanders engaged in armed confrontations with the government only as a defensive move. In contrast, the MNLF positioned itself as the Philippine government's ally by calling for a cessation of armed hostilities.

Finally, as the controversy over the peace accord subsided, the MILF and the MNLF also held polemic representations about the possible avenues to move the Mindanao peace process forward. According to the MILF, the peace agreement between the Philippine government and the MNLF had failed to address the roots of the Mindanao conflict. Hence, the MILF-backed 2008 peace agreement represented the most effective tool to push the peace process forward. The MNLF strongly countered this assertion and instead highlighted the centrality of the previous peace agreements that it had negotiated with the Philippine government, citing how these accords represented the best possible option to end the Mindanao conflict.

Summary: Highlights of Results

Do the social representations of a territorial peace agreement vary in relation to ethnopolitical fragmentation between Muslim nonmigrant groups in Mindanao? Our findings from Study One showed that whereas Christian settlers held hegemonic representations about the 2008 peace agreement, Muslim nonmigrants from two distinct territories, Cotabato and Zamboanga, held fragmented representations in relation to this particular social object. Study Two further substantiates these findings by examining the social meanings which two Muslim ethnopolitical groups — the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) — ascribed to the 2008 peace agreement. Results supported the patterns of Muslim ethnopolitical fragmentation observed in Study One, as these two resistance groups illustrated polemic representations about the Memorandum of Agreement.

We point out that both studies showed how the Tausug-associated Muslims positioned themselves along with the Christians’ contradictory stance against the peace agreement, leaving only the Maguindanaoan Muslims supporting the controversial peace proposition. Hence, the findings of our two studies provide evidence for the need to study ethnopolitical dynamics within a single religious category during the negotiation of territorial peace agreements in a so-called Muslim–Christian conflict.

Discussion

Using social representations theory as a conceptual lens, this research argued for representational fragmentations within the Muslim nonmigrant group rather than the Christian settler group, because different Islamised tribes carried ancestral attachments to separate territorial tracts included in the peace agreement. Research findings showed internal fractures along ethnic lines especially as the peace process progressed. From a shared religious category of the nondominant group Muslim or Moro, antagonistic ethnopolitical faultlines associated with particular ancestral domains emerged.

In the Mindanao conflict, war was encoded in the language of religious categories. Hence, at the peace bargaining table, the Christian government thought about one Muslim Front and a single unified Bangsamoro. But there was a different psychological picture on the other side of the bargaining table. Mindanao Muslims may not have seen all Islamised tribes as having equal collective rights over the territorial spoils of war. Fragmented ethnopolitical faultlines emerged as political talk veered away from an anti-Christian struggle to the sharing of power within Bangsamoro.

Our research highlights the power of social representations to nuance meaning-making within bigger social groups who are involved in peace talks. The conventional way of analysing conflict and peacemaking is through broader categories such as religion. But based on our results, viewing underlying ethnopolitical contours of larger conflict-based categories may add to a deeper understanding of a territorial peace process. Our results concur with other research findings that Muslims have an identity divide (Buendia, Reference Buendia2005; Frake, Reference Frake1998). Bertrand (Reference Bertrand2000), for instance, observed that ‘divisions among Muslims have reduced support for the peace agreement’ (p. 49). In territorial conflicts, larger or deeper divides may emerge once the peace talks address territorial issues.

What are the practical implications of our findings? We first relate our results to peacebuilding in Mindanao, and then elucidate on implications in other tribally contoured conflicts in the Pacific Rim.

One implication is that understanding the nature of peace in Mindanao entails looking beyond a conventional clash-of-religions narrative. The Mindanao conflict is popularly labeled as a Muslim–Christian conflict. Attempts at peacebuilding include formation and training projects that widen cultural understandings and increase tolerance of each other's religions. But underneath the religious umbrella of the Islamised nonmigrant and displaced group, there are tribal contours that turn salient as peace talks discuss territorial dominion over land ceded by the dominant Christian state. Hence, peace discussions should include not only whether particular spaces would fall under Christians or Muslims, but also how the territory ceded to the Muslims would be shared and managed by the different Islamised tribes.

The recent peace fiasco of 2008 demonstrates how Islamised Tausugs positioned themselves against a Memorandum of Agreement that was backed by the Maguindanaoan-associated Moro Islamic Liberation Front. For an explanation, we look at intertribal political competition. The reason behind the Tausugs’ criticism of the peace agreement may have stemmed from a collective Tausug desire for tribal control of any Moro Nation that would arise after the peace agreement. If the 2008 peace agreement had been signed, the Maguindanaoans would dominate the new Bangsamoro. This was probably what many Islamised Tausugs were avoiding as they criticised the 2008 peace agreement.

Long-lasting peacebuilding in Mindanao would entail addressing the politico-ethnic contours of Islamised tribes in the new Bangsamoro. However, the history of Mindanao peacemaking in the Philippines does not seem to recognise the underlying tribal contours. The discourse during peace talks is only about a single Muslim territory referred to, across recent history, as the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) associated with the Tausug-led Moro National Liberation Front, or the Bangsamoro Juridical Entity (BJE) in the 2008 failed peace agreement with the Maguindanao-influenced Moro Islamic Liberation Front. Understandably, both peace instruments did not mobilise a united Muslim front because support for or against the peace agreement fractured along tribal lines.

Assuming, however, that the peace discourse recognised ethnic coagulations, what would be the practical consequence on peacebuilding in Mindanao? We see two options. First, instead of a single Bangsamoro political entity, discussions may veer toward the creation of two Bangsamoro entities or substates, associated with the two dominant Islamised tribes in Mindanao.

A second option would be to open the doors to Muslim-based third party interventions that would encourage the liberation movements associated with the Tausugs and the Maguindanaoans to work together and craft the power-sharing contours of a single Bangsamoro state. Perhaps the superordinate goal of successfully getting back ancestral land now in the hands of Christians can bring the Islamised tribes together toward a more unified front. Informal and unverified political rumours have talked about the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) organising such meetings between the MNLF and the MILF. For ethical and politico-psychological reasons, however, it is worthwhile to mention that all three of us authors are Christians who believe that such third party interventions should not be initiated by the Christian-associated Philippine government or nongovernment organisations, as the issue is an internal matter among Islamised tribes.

Our research findings may likewise hold practical implications for other ethnically contoured contestations in the Pacific Rim. In the North Atlantic, cultural melting pots and multiculturalism are characterised by migrants from different parts of the globe. In the Pacific Rim, however, cultural heterogeneity is marked by variations of nonmigrant cultural groups whose ancestors have lived on their lands for hundreds of years. Hence, tribal identities in the Rim emerge during contestations about dominion over territory and resources in a certain place.

We point out that a larger conflict storyline in the Pacific Rim may actually hold invisible yet powerful tribal contours which may emerge once the bigger enemy cedes territorial control to the nondominant group. This may be the future of peacebuilding in the so-called large conflict between Christians and Muslims in Mindanao. There are also other societies in the Pacific Rim that may likewise need to attend to smaller tribal identities associated with the nondominant group, once the bigger antagonist bows out partially or completely from the contested territory.

Aside from the Mindanao conflict, we cite two other social conflicts in Pacific Rim where tribal-based peacemaking issues may arise within the nondominant group, as the major conflict with the primary dominant group subsides. For example, the Aceh movement for independence from the Indonesian state has been fuelled by Acehnese nationalism. Yet a closer look at the political picture on the ground shows that the Acehnese nation is composed not only of the Aceh tribe, but also of other tribes (Schulze, Reference Schulze2003) that include the Gayonese, Alas, Tamiang, Ulu Singkil, Kluet, Aneuk Jamee, and Simeulu (McCulloch, Reference McCulloch2005). In Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Bougainville struggle for autonomy from the PNG state has been marked with simultaneous intergroup struggles among the approximately 25 ethnolinguistic clusters among Bougainvilleans (Hammond, Reference Hammond2011). Interestingly, Bougainville has attended to its internal ethnic contours by implementing a peace process that recognises its ethnic variations and by developing a system of representation that includes clan, village, and area council chiefs (Reagan, 1999).

Practical applications of our findings may likewise be extended to regions beyond the Pacific Rim where there are latent yet fractured ethnic narratives embedded in a larger war storyline. This may be the case in the future of countries that are tribally configured, such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen. After a foreign enemy departs or an authoritarian leader falls, tribes that do not share the same ancestry, language, and territorial domains would need to strike a final peaceful arrangement among themselves, as the war-and-peace conversation veers away from a defensive armed struggle against an external enemy, to sharing dominion over ethnically contoured territory. For example, even as we write this article, there is news coming out of Libya claiming that rival tribes are violently feuding over the coming polls, in a new democracy won by a painful people's struggle against the Gaddafi dictatorship 8 months ago (Davies, Reference Davies2012). Indeed, the next-level peace narratives in both territorial conflicts and democratic movements may need to be about tribal power sharing.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support provided to Cristina J. Montiel from an Ateneo de Manila Loyola Schools Scholarly Work Grant and an AusAID-ALA visiting fellowship grant to the Centre for Dialogue at La Trobe University.