Introduction

This article introduces the first stage of a comparative study of the institutional arrangements for early years childcare policy (ECEC) in Brazil and Denmark. In many states, children are enrolled in kindergartens, preschools, or nurseries from the age of three. Parents enrol their children because they need to work or to prepare them socially for a life outside the domain of privacy and family or both (West et al., Reference West, Blome and Lewis2020). As many examples around the world show, childcare services are designed to provide services and care focused on families’ needs (e.g., Campbell-Barr and Coakley, Reference Campbell-Barr and Coakley2014; Prentice and White, Reference Prentice and White2019; Windebank, Reference Windebank2017). The expression “early childhood education and care” identifies both education and care and therefore masks their complex interaction (Staab, Reference Staab2010; Ellingsæter et al., Reference Ellingsæter, Kitterød and Lyngstad2017) and hides the dimension of discipline. Emphasising this interaction as a civilising process is a way to show this complexity. The concept of “care,” when applied to public childcare policies, is complicated because on the one hand, childcare implies care by people other than parents; however, on the other hand, it has been seen as necessary to interfere with parenting itself (Sundsbø, Reference Sundsbø2021). Here, the availability of public care is seen as the provision of a service of support for families, aside from any assumptions about parental competence.

There are comparative studies of this subject which feature more than two countries (see European Union, 2019 for a large example, or Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013 for a more closely grained study). They show a similar trend across nations, albeit at varying paces, in which shared economic and demographic changes can be detected as key drivers (Hill and Møller, Reference Hill and Møller2019). This study, in choosing just two nations, is influenced by a view that there is a need to develop comparative approaches that go further to explore how different policy intentions are translated into civilising processes where the influences in play lie nearer the childcare arrangements at the “street level” (Hill and Hupe, Reference Hill, Hupe and Hupe2019; 2022 chapter 10).

In times of increasing inequalities there are important questions to be considered about how social cohesion, integration, and a sense of belongingness can be achieved. Here, understanding how childcare arrangements at the street level influence policy in practice are salient. Our upbringing of children is constitutive of our societies’ existence (Goerres and Teppe, Reference Goerres and Tepe2012). And states’ investment in children’s development matters for the way societies can enhance a more even distribution of life chances across populations and thereby affect future inequalities (Heckman, Reference Heckman2011). The classic dictum “it takes a village to raise a child” denotes the social complexity of child raising as a task going beyond parents and involving broader social networks. It takes a state, a country, or a nation as a large-scale social context capable of nesting children’s way into joining society’s social order. Many questions about how (the causal links between childcare and increased life chances for individuals), when (at what period in a child’s life does childcare matter?), where (what sites are used to carry out childcare?), what (the content of childcare?), and why (childcare increases life chances and contributes to social cohesion?) are important. However, improving life chances for children and strengthening social cohesion are two potentially antagonistic objectives as succeeding on the first goal may change social structures so that success on the second goal is unlikely. In this article, we focus on the “what” question to explore the use of childcare policy to nest children into the social order. We do this by first contextualising social cohesion and childcare historically, then by exploring state action – childcare policy and educational guidelines. We see childcare policy as a “civilising process”: characterised by the policy practice governing the roles of care providers and professionals in public and semi-public settings. In the historical analysis and in the analysis of the policies and educational guidelines, we show how this civilising process is designed to face social inequalities and differences and at the same time generate social cohesion through childcare.

We take the kindergarten and early childhood education and care as loci where the social inequalities may be materialised but also where the state may create solutions to reduce inequality and promote social cohesion. In this way, we consider a particular aspect of institutionalised childcare – the state role in civilising childcare – as an idea and as a profession of child development also responsible for generating (and conserving) social cohesion as well as reducing inequalities among children.

The article is structured as follows: After a presentation of sociological ideas on the civilising processes and pedagogical ideas on child development, we outline our findings set out as, first, some broad historical generalisations about developments in the two countries and, second, empirical comparative analyses of policy instruments exploring the characteristics of childcare policies and educational guidelines. In the conclusion, we discuss whether childcare is an example of how the state deals with antagonistic objectives of simultaneously conserving social order to ensure cohesion across unequal social groups and changing the social order and patterns of social cohesion by childcare investment to reduce future social inequalities.

How do states raise their children?

To see a connection between structures of society and people’s behaviour and psychological habitus is far from a novel discovery (Elias, Reference Elias1994: xiii). This identifies the sense of belongingness across different social groups embedded in civilising institutions such as churches, labour markets, schools, and kindergartens, places which Elias refers to as places where individuals internalise such impulses of belongingness through social interactions. We see ECEC as a civilising institution and the social interactions between childcarers and children as part of the civilising process. We recognise that this usage has been challenged inasmuch as in Elias’ work; there are elements of the notion of a universal modernisation process and European cultural superiority, but we accept van Kreiken’s (Reference Van Kreiken2005) argument that there is within this theory “a more objective understanding of those social and political conditions, practices, strategies and figurations which produce whatever ends up being called civilization, founded on a reflexively critical awareness of the way in which particular conceptions and experiences of ‘being civil’ get constructed and produced in one way or another” (van Kreiken, Reference Van Kreiken2005: 41). This view is taken up by Gilliam and Gulløv (Reference Gilliam and Gulløv2017) in their analysis of Danish childcare and education policy explaining how the civilising process encompasses the perspectives afforded by related concepts such as “disciplining,” “educating,” “childrearing,” and “socialisation.” There are parallels here to Foucault’s analysis of the relationship between modern medicine and civilising processes (Reference Foucault2012). We use this interdependency between structures of society and identity formation to highlight the state’s need to engage in the civilising process, while acknowledging the complexity of creating, controlling, and implementing activities that empower citizens to live, belong, and contribute to society at large.

Pedagogy, care, and education

An examination of surveys of policies in Europe suggests two approaches to the relationship between care and education (European Union, 2019). One approach sees the early and later needs of children as rather different and to be addressed in different ways. The other approach regards integration of care and education as needing to occur across the whole preschool age spectrum. Critical accounts of systems tend to start from the latter as the ideal and implies a need to measure the ways in which actual systems fall short of that ideal (see, e.g., Cameron and Moss, Reference Cameron and Moss2020 on England). These accounts often bring into play the term pedagogy. This can be confusing since the term is shared by many European languages to mean the science of teaching but comparatively rarely used in English. What is important here is that the term is used when a case is made for an activity (in some places, it is simply seen as pedagogy and in others, simply as early years teaching) which implies much more than simply imparting skills and knowledge. Its usage is therefore compatible with an overall emphasis on the civilising process.

In line with this argument, Vandenbroeck makes a powerful distinction between “banking education” and “problem posing education” (Vandenbroeck, Reference Vandenbroeck2020: 4). He quotes Freire defining the former as a concept of education where “knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those they consider knowing nothing” (Freire, Reference Freire1970). Vandenbroeck argues that “The language of skills is… very different from the language of values” and goes on to argue that “choices can (and should) be debated on the image of the child, the image of the adult, the image of society and ultimately, the image of what early childhood education is for” (Freire, Reference Freire1970: 22). He criticises views of early years education which see it as simply to create “productive citizens,” as in discussions of “social investment” (Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2004; Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2015).

Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw (Reference Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw2020) express similar concerns, seeing pedagogy in terms of an ambitious expansion of its Greek roots as “the formation and education of the ethically and spiritually complete citizen, … a cultural form that guided children’s insertion into society… concerned with the creation of a collective humanity” (Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw2020: 631). This means for them, as for Vandenbroeck, a challenge to the way the prevailing political and economic order (for them “the capitalist project”) dominates the pedagogical agenda. But they also particularly single out the role of developmental psychology moulding “the child into an ideal citizen who will serve an already-specified society” (Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw2020: 633).

These observations help us to identify an approach to the comparative study of ECEC where the critique of existing policy, expressed in terms of an ideal pedagogy, provides a comparative yardstick. It highlights issues about the shape of policy in different places in terms of the extent to which care and education are integrated. It points towards certain specific issues, for example, the roles of staff and the educational requirements for their work, the ways in which practice needs to vary as children age, the extent to which specific activities are required and how the transition to primary schooling is handled. And, importantly, it highlights questions about the extent to which ECEC is seen as a universalist service, or alternatively fragmented in terms of divisions based upon capacities to pay or assumptions about social and cultural need variations. In other words, it highlights the state’s use of childcare to civilise.

As noted earlier, “pedagogy” is first and foremost “a body of knowledge” and even a social science in some countries (Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw, Reference Vintimilla and Pacini-Ketchabaw2020). Over time, pedagogy has found autonomy as a discipline of thought engaged with knowledge creation and in some countries even as a profession claiming not only the term but also educational jurisdiction and practical training in specific childcare institutions. That brings concerns about education and childcare alongside family policy as a significant element in the study of social policy. Pedagogues in ECEC must teach children to see and understand themselves outside the domain of privacy, and they teach and train them in how to engage and perceive meaningfully larger social contexts outside the kindergarten and the private home. They can be both private and public practitioners.Footnote 1 They are often regulated by the state and provide childcare for the state following national guidelines on how to turn ideas on social virtues into doable activities in the encounter with children. Pedagogues have the responsibility (on behalf of the state) of civilising and empowering the child to be part of society.

Towards a systematic interpretive study of policy intentions and educational ideas about childcare

Gillam and Gulløv (Reference Gilliam and Gulløv2017) advocate studying civilising processes as site-specific practices to be studied as contextualised layers of evidence, rather than as outcomes of variations on particular dimensions. This approach provides insights into what explains outcomes. Even though scholars from different methodological traditions seem to agree that structural factors such as the style of bureaucracy and the political economy of the welfare state matter at an individual level, we still need more structured analyses of the iteration between macro- and micro-level sources of influences of everyday life to expand our insights about how national aspects of social, political, and narrative dimensions nest individual and organisational responses to citizens (Møller, 2019: 104).

Studying early years, childcare comparatively highlights civilising as a process. There are inevitable similarities in the activity between societies and shared developmental pressures within societies such as democracy, changing families, and labour markets (Windebank, Reference Windebank2017). Also, the choice allows for a place-based approach to generate important knowledge about how broad macroprocesses shape our political and social worlds (Simmons and Rush, Reference Simmons and Rush2021: 15). We expect cultural differences to affect the way issues are framed and anchored in communities by different social groups including, in this case, childcare workers and pedagogues. The state seeks to make sense of the wider social issues which impinge on how policies are eventually constructed in terms of intentions about issues such as inequality, ethnic diversity, and the organisation of family life (Campbell-Barr and Coakley, Reference Campbell-Barr and Coakley2014).

Comparing ECEC in Brazil and Denmark: Analytical strategy and empirical foundation

To analyse how states, through civilising processes, raise their children facing unequal social structures and constructing social cohesion, we use an interpretive methodology as proposed by Fairclough’s three-dimension model (Reference Fairclough1992: 73). To represent the social context of our research question, we selected two country-contexts that share an equivalent task but different context characteristics, as proposed by Hill and Møller (Reference Hill and Møller2019), and to represent discursive events, we selected policy documents and educational guidelines (Fairclough, Reference Fairclough1992: 73). Following standards from comparative methodology (Landman, Reference Landman2008; Sætren, Reference Sætren2014; Hill and Hupe, Reference Hill, Hupe and Hupe2019), good comparative work must rest upon precise specification of the contexts to be compared. By contrast with macro-comparative studies, we contrast the selected task of childcare more than we compare contexts (Schaffer, Reference Schaffer, Simmons and Smith2021). Brazil and Denmark were selected as countries that share childcare as an equivalent task. Being interested in the state role in civilising childcare, they share an ideal of pedagogy in childcare, however not the same level of resources. This allow us to study whether policies are already adopted towards local needs or are formulated independently of these. Furthermore, the task of childcare is chosen as it meets the requirement that it is general enough to feature in both country contexts without being trivial or only a minor part of some more important task. Childcare in both Brazil and Denmark has the function of caring and educating children while their parents are working (Hill and Møller, Reference Hill and Møller2019: 15).

At the same time, they have dissimilar national cultures and experiences regarding inequalities and, consequently, systems for redistribution, and prosperity. They also have highly distinct democratic experiences in terms of length and polity structures. Drawing on historical sources in both countries, the analysis of different contexts (Seawright and Gerring, Reference Seawright and Gerring2008) is specified to present their history of social cohesion and childcare policy, as well as to the policy intent of pedagogy work at kindergartens. We illuminate the relationship between the state and childcare by first contextualising the historical pathways of childcare in the two countries followed by a policy analysis of selected policy documents and educational guidelines contrasting the last 30 years of developments in childcare policies, instead of measuring controlled and uncontrolled variation (Schaffer, Reference Schaffer, Simmons and Smith2021).

Method

To contextualise the countries’ current childcare historically, we used historical sources found through standard reading of the literature while doing background research for the policy document analysis. For this, we selected policy documents and educational guidelines about the state’s use of childcare with relevance for the task of childcare in kindergartens published between 1990 and 2020 in the two countries. We chose this period because there was an explicit process of framing ECEC policies such as an increase in national regulations over ECEC in both countries together with a movement of qualifying childcare professionals (Mandag Morgen, Reference Nunes, Corsino and Didonet1998; Machado, Reference Machado2000; Nunes et al., Reference Prentice and White2011).

In Brazil, federal policy documents were identified and selected through systematic search in the database of the federal law and the Education Ministry homepage. In Denmark, policy documents were identified and selected through systematic search in the database of the national laws and executive orders. We used the Portuguese and Danish words for pedagogy, pedagogic, pedagogue, early-childhood education, kindergarten, pre-primary, day care institutions, and basic education.

Regarding the educational guidelines, we included curricula and study plans from professional colleges.

In total, 44 documents were selected (19 policy documents and educational guidelines documents from Brazil and 25 from Denmark) and imported into the QSR software program NVivo to support comparative document analyses.

Policy analysis

All policy documents and educational guidelines were classified based on document type (policy or educational guideline), year of publication, and country (or state) of origin. Analyses were done by qualitative content analysis coded systematically in NVivo (see coding frame in Appendix). After an initial phase of open coding, the coding strategy has been mainly deductive. Codes are rather broad and inclusive, and methodologically, we adopted an abductive coding as our approach to revise and adapt the coding frame several times during the coding process (Tavory and Timmermans, Reference Tavory and Timmermans2014). Method-wise, we used constant coding comparison to help us identify meaningful resemblances and differences in the data (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) We did this to sensitise dimensions of codes (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006) relating to policy intention, educational content, and organisation of pedagogical work in inclusive, transparent, and authentic ways (Dahler-Larsen, Reference Dahler-Larsen2008).

We faced challenges of understanding, sharing, and interpreting how concepts were used in the original language (Portuguese and Danish) and how to translate these into our “shared” language (English). Concepts, readings, and coding results were discussed to check consistent usage. An example of a particular difficult content to capture was represented by semantically different word families such as emancipation (pedagogue), academia (professor), education (teacher), and caring (childcarer). As we wanted to understand what practice these words represented, to make sure we captured functional equivalent meaning from these words (here, that they did perform educative and caring kindergarten activities), we discussed the words and their uses in language and in practice (Schaffer, Reference Schaffer, Yanow and Schwartz-Shea2014). After agreeing on how to interpret the represented meaning, we repeated an inclusive coding of all texts followed by two reliability tests, where one research member re-coded a representative piece of text in each country. Then, all inconsistent coding was translated from Danish and Portuguese into English and was discussed again across research teams before an interpretation of ambiguous terms, and texts were agreed upon and re-coded accordingly.

Contextualising the state role in Brazilian and Danish childcare

Both Brazil and Denmark have extensive (ECEC) sectors, and they draw on some of the same philosophical sources in terms of understanding and creating institutionalised childcare which can help overcoming social problems (Freire, Reference Freire1970). At the same time, both countries represent extreme cases regarding inequalities: Denmark is one of the more equal countries in the world, while Brazil is one of the more unequal countries. Analysing the state’s role in civilising children through childcare in these different contexts enables us to interpret and explain how and why the state uses childcare as a tool to reduce inequalities and strengthen social cohesion.

With the adoption of the Constitutional Act in 1849, Denmark went from absolute monarchy to representative government. However, full democracy was not introduced until 1915, when women were enfranchised. Denmark changed – from absolute monarchy to full democracy – into a small-scale, strong welfare state in terms of economic and social redistribution, transparent structures of regulation, and with a high degree of public trust in its political institutions (Svendsen, Reference Svendsen2018). With these intensified state–citizen interactions, social cohesion became dependent on citizens’ predictable public space behaviour as an intense shared public identity and sense of belongingness to the idea of an omnipotent welfare state present in almost all areas and stages of the citizen’s life. This form of social integration required a degree of homogeneity, which is now being challenged by an increasing heterogenic population (primarily caused by immigration and rising social inequality) (Villadsen and Hviid, Reference Villadsen and Hviid2017: 47–48). Deviance and non-belongingness became a problem for the state not as a matter of how to exclude uncivilised citizens, but as a matter of how to include them in the civilising process. Barriers to inclusion became perceived as caused by a problem of citizen adaption and assimilation to the welfare state’s core institutions. For this reason, the Danish state saw new opportunities in childcare as a site to perform crucial civilising processes as a means to overcome these barriers and strengthen its cohesion through new forms of institutions capable of socialising the public on an individual level. Seen in this light, civilising childcare became a key site to ensure a profound introduction into the Danish society (Villadsen and Hviid, Reference Villadsen and Hviid2017).

Brazilian society was and is still characterised by heterogeneous populations and social inequalities. A history of colonialism, the indigenous populations’ genocide, and three centuries of slavery generated an unequal society marked by racism and other forms of discrimination (Almeida, Reference Almeida2020). After the end of colonialism and slavery, other socioeconomic mechanisms reinforced unequal structures, limiting the access of marginalised groups to rights and to welfare. The Brazilian welfare state was created with the constitution of 1988, which also re-democratised the country after almost 20 years of dictatorship. The new constitution aimed at constructing a new democracy, providing universal and public services to the population, increasing the idea of universal rights, and reducing inequalities. However, this transition was not followed with a broad change in social structures. Therefore, racism remains systemic and structural (Almeida, Reference Almeida2020) and – as inequalities are multidimensional – it can be seen in income inequality, unequal access to rights, and unequal distribution of power (Costa, Reference Costa and Pires2019). Brazil has therefore developed into a minimal welfare state divided into a small elite, a middle class, a large working class, and a proletarian class with limited rights and options for inclusion into the country’s social, political, and cultural resources. Integration and diversity in terms of representation are challenges for the state’s civilising project.

The two countries represent opposing extremes in terms of inequalities. In a ranking of 162 countries based on the Gini index (the first country being the most unequal and the last one the most equal), Brazil is in the 16th position, while Denmark is in the 148th position (Gini index, 2023). In both countries, the development of early childcare began as a bottom-up process during the 19th century where day care centres were designed to take care of the children while their parents were working (Borchorst, Reference Borchorst, Melby, Ravn and Carlsson Wetterberg2006; Nunes et al., Reference Prentice and White2011). Those institutions were attended by children from lower classes, children of single mothers, orphans, or abandoned children (Nunes et al., Reference Prentice and White2011; Schwede, Reference Schwede, Ankerstjerne and Broström2015).

In the 20th century in Denmark, childcare became a solution to a broader need for social cohesion between families and the labour market, as well as a way for the state to discipline lower class children to develop skills to climb up the social ladder and thereby reducing social inequality between resourceful and less-resourceful families (Fraisse et al., Reference Fraisse, Andreotti and Sabatinelli2004). In Brazil, sites of childcare also became seen as political options for fixing problems of social cohesion. At first, there was a dual system in Brazil: Kindergartens managed with a social assistance perspective with the duty to attend to poor children and, simultaneously, kindergartens with an educational perspective that were attended by children from wealthy families.

In both countries, ECEC started as a solution to the problem of women’s inclusion in labour market. In Denmark and Brazil, early childcare became an instrument for realising labour market policy and legislation between the 1940s and the 1960s, where, at the beginning, companies were obliged to provide ECEC institutions for children of working women.

During the 1960s, childcare was institutionalised as a public service in line with public health service and other social services. In Brazil, in 1961, the Guidelines and Bases of National Education aimed at implementing ECEC for children up to 7 years old in nursery schools or kindergartens. And in Denmark, in 1964, legislation (“børneforsorgsloven”) turned childcare into a universal public service, and with the Aid Act (bistandsloven) of 1974, the use of institutionalised childcare was designed as a local public task by giving the municipalities the responsibility of providing early childcare.

These processes moved the countries towards national versions of integrated care and education among all social groups throughout childhood with a demand for professionals in kindergartens. Along with these processes, pedagogy was (re)invented as a new profession aimed to provide childcare as a service not only for parents (caring and minding while at work) but also for the children themselves (educating them with personal competences to belong to the broader society).

However, even though childcare as a task has similar roots in terms of being created in local communities to serve local needs, the roots of pedagogy were quite different. In Brazil, the first pedagogy course was created within the National Faculty of Philosophy to “prepare candidates for the teaching of secondary and teachers college education” (Brasil, 1939, art. 1). Childcare was not introduced into pedagogy courses before the 1970s. In this way, it was the development of a teaching profession which paved the way for training kindergarten staff. Eventually, an integrated approach to childcare was developed for the different graduating candidates of pedagogy (Fontanella, Reference Fontanella2011).

In Denmark, this process started already in the 19th century with a demand for a more professional approach to early childcare. The first kindergartens were inspired by the German philosopher Frederich Fröbel who advocated a child-centred pedagogy based on the idea that early child development should be stimulated through play. The education of teachers for public schools was never part of the formation of pedagogy. Hence, its professional development increased in the middle of the 1940s with more educational programs for employees in childcare services established around the idea of pedagogy and not education as in Brazil.

In Denmark, the international debate within the OECD and the EU pushed an approach seeing early childcare and education as an investment in a better future and thereby made a direct connection between quality day care and economic growth (Dahl et al., Reference Dahl, Hansen, Hansen and Kristensen2015). In the same period, there was an increasing criticism of the lack of regulation of the quality of ECEC. This critique came both from the responsible municipalities as well as from organised pedagogues (in a worker-based union; Mandag Morgen, Reference Nunes, Corsino and Didonet1998). Also, Danish pedagogical scholars began to highlight pedagogy as a tool to socialise children to become empowered individuals capable of actively participating in society, with ideas and reasoning inspired by, among others, the Brazilian theorist Paulo Freiere (Jerlang, Reference Jerlang1995). During the same period in Brazil, a process of democratisation was enacted through the National Constituent Children’s Commission, which emphasised children’s rights to quality day care (Nunes et al., Reference Prentice and White2011). This process also stimulated a movement for more qualified professionals (not just child-minders) in ECEC (Machado, Reference Machado2000). Finally, the 1988 Brazilian federal constitution, established a duty for the state to delegate childcare responsibility to the municipalities, including universal kindergarten access for all children between birth and the age of 6 (Brasil, 1988, article 208).

These similar developments towards including care and pedagogy in state-initiated local childcare provision, turned childcare into a site of civilising state projects and eventually moved childcare away from a task that was just using childcare as minding children for parents on the labour market. The pace of these developments differed, but childcare nevertheless became a tool in both countries to promote social cohesion and inclusion. Here, contrast is significant with respect to the development of pedagogical concerns within ECEC between a development pioneered by an independent organisation in Denmark and the evolution in Brazil of a state-driven extension of the pedagogical concerns from within education as a whole.

Policy intentions in Brazilian and Danish childcare

For this second part of our evidence, we studied policy documents and educational guidelines about the state’s use of childcare with relevance for the task of childcare in kindergartens published between 1990 and 2020 in the two countries, which was a busy period in terms of framing ECEC policies in both countries (Mandag Morgen, Reference Nunes, Corsino and Didonet1998; Machado, Reference Machado2000; Nunes et al., Reference Prentice and White2011).

Comparing policy intentions

Brazil and Denmark’s ECEC policies were formulated within similar time periods and share important characteristics aimed towards regulating the quality of public ECEC services. The integration of care and education has been prioritised through formalising learning goals in educational guidelines. However, in terms of the policy, there are many differences, particularly with respect to objectives (Table 1).

Table 1. Policy intention content in childcare policy documents from 1990 to 2017.

Cell content: Number of times we identified code content in the documents (marked with * in the references). Percentages display relative significance of the codes within each country.

These differences can be seen in the documents with respect to objectives about care, pedagogical learning, social cohesion, and preschooling.

Caring as a policy intention is giving meaning by references to values such as “parent payment,” “finance,” “physical requirements,” “responsibility for services,” “access requirements,” and “hygiene and safety” in the policy texts from both countries. Values regarding “learning,” “development,” “competences,” and “wellbeing” were identified across policy texts as important for pedagogical learning. With respect to the policy intention of creating stronger and better social cohesion through ECEC polices, “inclusion,” “special support,” and “equality” were mentioned in texts from both countries. Regulations and guidelines regarding transition between day care services and schools were highlighted as an objective demanding collaboration between schools and kindergartens. These values were presented in “chains of equivalences,” where one value became seen as meaningful by association with the others. The way texts use chains of equivalences, instead of chains of differences, where words get their meaning from being represented in an opposition to other words, indicates a newness of the discourse, where values and associations are (still) unstable and highly contingent on each other to make sense (Laclau, Reference Laclau and Mouffe2014: 113).

In Denmark, the pedagogical elements refer to the improvement of child wellbeing and how to create a pedagogical environment that will support learning, development, and socialisation as in the following example from a Danish policy document:

“Child care must promote children’s well-being, learning, development and education through safe and educational learning environments, where play is fundamental and where the point of departure is from a child’s perspective. (…) In collaboration with the parents, child care must provide children with care and support the individual child’s well-being, learning, development and education, as well as contribute to children having a good and safe upbringing. (…) Child care must give children co-determination, co-responsibility and an understanding of and experience with democracy. As part of this, child care must contribute to developing children’s independence, abilities to enter into binding communities and cohesion with and integration in Danish society” (Børne- og Undervisningsministeriet, 2018: 7).

ECEC should be based on building a safe learning environment, where play is a central element in learning activities and based on a child’s perspective. The child’s perspective is written into the law to clarify childhood as a value on its own terms. Furthermore, ECEC is expected to prepare children to be part of a democratic society in a globalised world. Childcare services are represented as tasks that must promote child well-being and be dependent on particular physical conditions capable of promoting learning and a healthy psychological environment. Most of the pedagogical part of the policy documents refers to the implementation of the pedagogical curriculum, mandatory in the Child Care Act in 2007 which stresses six specific themes: “child development,” “social skills,” “language and communication,” “body and motion,” “nature and science,” “culture,” and “community.”

In the Danish policy documents, a range of policy tools are mentioned as available to pedagogues who are expected to approach social background as a condition and not as a determining destiny. This approach is also represented in the professional guidelines (the pedagogical curricula), which are scripted with special attention to the inclusion of children with special needs (made meaningful primarily through references to a disability discourse and, to a lesser degree, to an inequality discourse).

In the Brazilian policy documents, the objectives of “pedagogical learning” and “social cohesion” are given similar attention, while content is somewhat different as in the following example from a policy document:

“Entry into child care or preschool means, in most cases, the first separation of children from their family emotional ties in order to be incorporated into a structured socialization situation. In recent decades, the concept that links education and care has been consolidating in Early Childhood Education, understanding care as something inseparable from the educational process. In this context, child care centers and preschools, by welcoming the experiences and knowledge constructed by children in the family environment and in the context of their community, and articulating them in their pedagogical proposals, aim to expand the universe of experiences, knowledge and skills of these children, diversifying and consolidating new learning, acting in a complementary way to family education – especially when it comes to the education of babies and very young children, which involves learning very close to both contexts (family and school), such as socialization, autonomy and communication” (Ministério da Educação, 2017: 36).

Whereas in Denmark, social and educational equality and inclusion of children with special needs are stressed, the Brazilian ECEC policy documents also target the protection of cultural diversity. Diversity is described as reflecting “mutual respect”; “valuing the diversity of cultures” and “ethnic-racial knowledge”; “combating racism and other forms of discrimination” (gender, religion, family compositions, etc.); and “building identity and positive self-image and belonging.” So whereas in Denmark, emphasis is on respect for individual differences and inclusion of children with special individual needs, in Brazil, “social cohesion” is represented as a matter of achieving social tolerance across different social groups.

With respect to the use of institutionalised childcare to civilise children so they can grow into included, empowered citizens, Danish ECEC policies emphasise “care” to signify this intention to a much bigger extent than Brazil, where in contrast, social group-belonging is highlighted as an important prerequisite for building a stronger social cohesive state. In Brazil, care objectives constitute a minor part of the National Standard for the ECEC policy and is far from the core of the policy.

This difference between the two countries highlights the need to understand the barriers crucial for the civilising process: the distinction between being socially and individually included. In Brazil, this barrier appears related to strong cultural scripted social group belongingness, whereas in Denmark, this barrier appears related to the organisation of care in lower-level government.

Educational content in pedagogical training

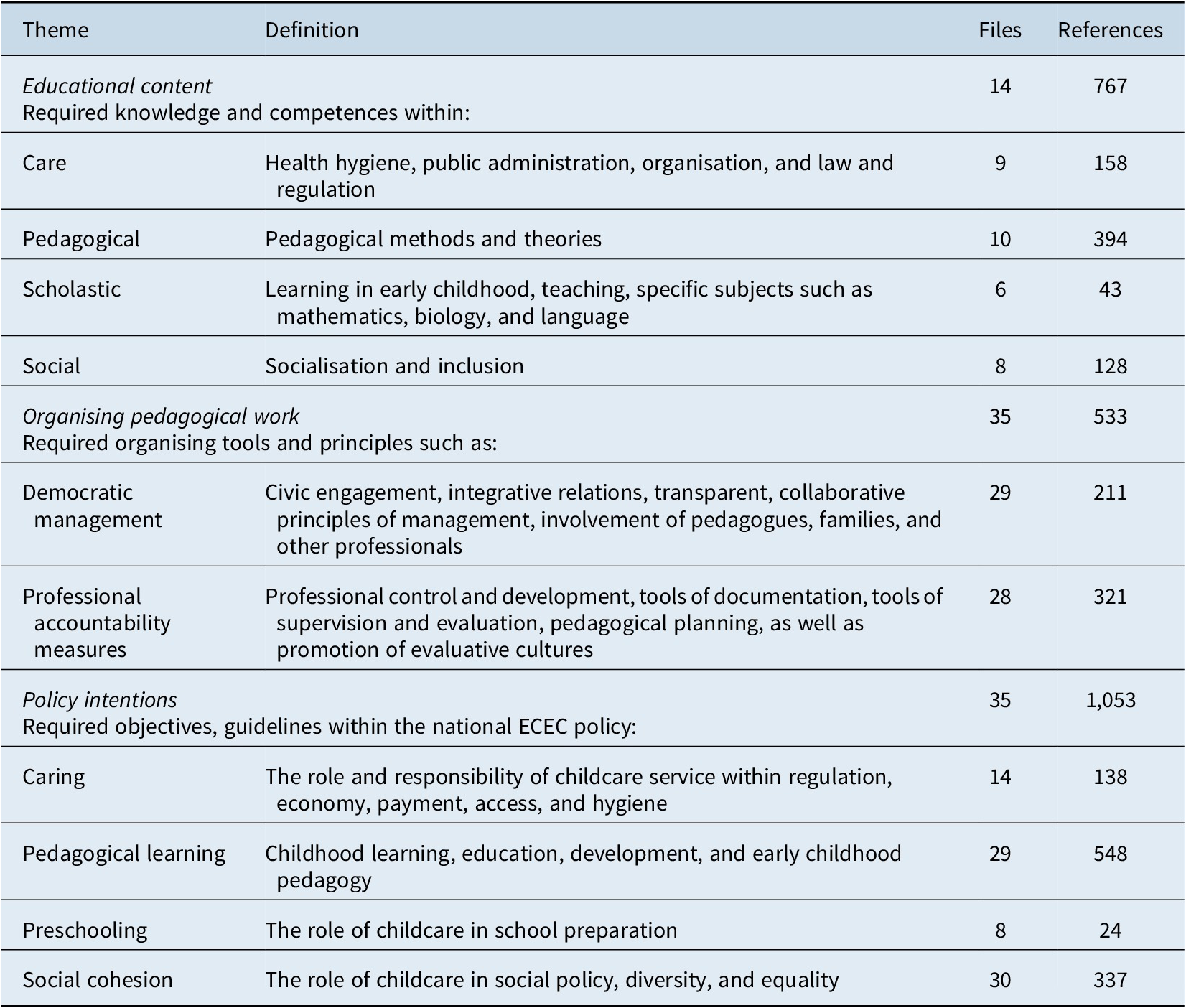

In both Brazil and Denmark, the training institutions are the primary target groups for the national visions of childcare and policy designs. Both countries introduced training programs, aimed towards disciplining staff in childcare services to comply not only with caring and education but also with pedagogical objectives to see children in the larger picture of society. The body of knowledge which characterises these programs is interestingly similar between the countries (Table 2).

Table 2. Educational content in educational guidelines from 1990 to 2017.

Cell content: Number of times we identified code content in the documents (marked with ** in the references). Percentages display relative significance of the codes within each country.

In both countries, the formal purpose of the pedagogical training is to teach students didactic theories on socioemotional and learning development as well as to teach them relevant competencies, knowledge, and skills to support such learning developments. The training consists of a common, a specialised, and a practical part, where the specialised part makes up two-thirds of the training, allowing students to specialise within early childhood pedagogy.

In the common part of the training curriculum, both Brazilian and Danish students must learn pedagogical theories, including knowledge about educational systems, private and public organisations, political institutions, and educational practices. They must also learn about society at large and about pedagogy as a profession, a philosophy, and as a civilising practice. These modern features of the training curriculum indicate how pedagogues are expected to fulfil an explicitly civilising role.

In Denmark, students must learn how to integrate nature and culture to support learning and development among children; and in Brazil, the emphasis in the training programs is on teaching students how to enact a pedagogical, scholastic, caring, and a social approach in their activities. They learn how to create a collective as well as an individual learning development by turning these dimensions of knowledge into practical activities. Students are expected to understand the children’s life context and be able to decode how each child can learn and be creative, taken their family background and local community context into account.

However, even though there are many similarities, there are also significant differences. In Denmark, a bachelor’s degree in pedagogy is not a requirement for working within ECEC, and in 2019, the share of fully trained staff in kindergartens was 57%, with large differences across municipalities (from 42% to 68%) (EVA, 2020). In contrast, in Brazil, the percentage of staff with a degree in pedagogy is higher (77%), but with larger differences across municipalities (from 0% to 100%). Also, the role of “care” and “pedagogy” in the educational content differs in attention within the two countries’ educational guidelines. In Denmark, relatively more emphasis is put on pedagogues’ roles as care providers in the sense of guaranteeing a safe space for children compared to Brazil, where policy documents pay relatively more attention in their professional guiding lines to explaining the pedagogical content. We interpret these differences as related to the two countries’ different barriers to social cohesion, and we see the consequences in how the educational guidelines prioritise a tight association between democratic principles and the organising of the pedagogical work.

Organising pedagogical work

In the educational guidelines of both Brazil and Denmark, values such as “democratic management” and “professional accountability” are emphasised as central to how pedagogical work should be organised. In Brazil, the guidelines use the term “democratic management” as a principle kindergartens should have, for example, as expressed in a Brazilian guideline in the following way:

“Participation, dialogue and daily listening to families, respect and appreciation of their forms of organization (…) The establishment of an effective relationship with the local community and mechanisms that guarantee democratic management and consideration of the community’s knowledge” or by “engaging the school community, by its representative organizations: the ECEC professionals, the parents, the families, and the children” (Ministério da Educação, 2010:19).

Although in Denmark, this specific term is not used, the same ideas are represented by terms such as “civic engagement,” “integrative relations,” and “collaborative principles of management”, as also emphasised in the following Danish guideline:

“As part of the work with the educational curriculum, the child care center must consider how the local community in the form of, for example, libraries, museums, sports facilities, care homes, businesses, and so forth can be included in order to strengthen the child care’s educational learning environment. (…). The day care service must also consider whether a collaboration with, for example, older citizens, schoolchildren from the intermediate level and secondary school or other volunteers in the local community who wish to contribute with a special knowledge or interest in, for example, nature, sports, music, health or crafts, can contribute to strengthen the work with pedagogical learning environments” (Børne- og Undervisningsministeriet, 2018: 29).

In both the Brazilian and the Danish educational guidelines, there is an emphasis on “professional accountability,” referring to how pedagogues should plan their work; how they should be qualified, managed, and measured; how they should register their activities; and how the children’s development should be monitored (Table 3).

Table 3. Organising pedagogical work content in educational guidelines from 1990 to 2017.

Cell content: Number of times we identified code content in the documents (marked with ** in the references). Percentages display relative significance of the two codes within each country.

Pedagogues in both countries are granted considerable professional autonomy. It is up to them to design and structure the content of pedagogical practice. They can also decide how to organise daily encounters within externally defined evaluation measures. In Brazil, kindergartens need to provide the child’s family with documentation of the child’s pedagogical progress, and in Denmark, the involvement of parents has been embodied in the law since 1992 specifying that kindergartens must achieve their purpose through a required collaboration with parents in the so-called parent boards. In both countries, the municipalities expect kindergartens to involve other relevant public or private actors who can play a relevant role in the overall civilising process of the child.

Hence, in both countries, childcare is seen by the state as a significant frontline for the creation of social cohesion. Overall pedagogues in both Brazil and Denmark are expected to be professionally accountable to larger social objectives: to discipline not only children, but the entire community around the kindergarten through ideas and measures of democratic management.

Conclusion

This study’s starting point was to understand the state role in civilising childcare. We adopted a perspectival comparison of two childcare settings, contrasting the development of childcare as a solution to the state’s problem of (re)producing social cohesion in two countries with very different characteristics: Denmark as a typical social democratic regime and Brazil, a country that – while hard to fit to any regime model – is certainly not seen in that regime category. Our starting point was not the standard comparative question: How much divergence or convergence is there? Instead, we asked, what can we learn by contrasting two diverse social contexts by comparing them with each other. Our analysis indicates that childcare is situated in complex, relational interactions between the political environment, national interpretations of democracy, and organisational structures. However, comparing complex sites can be done in structured ways and with a potential to elaborate on concepts and theories about, in this case, barriers of social cohesion and civilising processes. Using this interpretive approach to systematically compare policy documents and educational guidelines, we learned how the idea of pedagogy unfolded in two countries’ state narratives but also why these relations and dependencies have a functional universal character likely to play out in other country contexts as well.

Our research aims to understand the state role as it is expressed in educational policies and guidelines by creating (public) places suited for institutionalised childcare. We choose pedagogy because it is both an idea of civilisation used as a policy tool to reach other goals such as social equality, cultural equality, gender equality, and employment measures and embodies a frontline perspective about best practice for this task in highly complex country contexts. Brazil and Denmark represent highly different countries in terms of size, national culture, religion, political system, and economic distribution but share the idea and the practice of pedagogy and institutionalised childcare as a civilising tool to connect between the larger society and its children. By comparing childcare policy as a logic and a process occurring in two different sites, we analyse something beyond the power of country-specific factors, such as social coherence between policy and education ideas about civilising children in institutionalised childcare. We perform a perspectival comparison of these two different states by zooming in on how pedagogy is framed in policy and educational guidelines to play a state role in civilising processes of institutionalised childcare.

Often, the content of public policy is conceived as an outcome of politics, representing the larger social ideas and interests of society (Schneider and Ingram, Reference Schneider and Ingram1993). In contrast, our policy analysis shows how the content of a policy is also shaped by policy frontline arrangements not only as a practical option (does the country have kindergartens?) but also as an idea and as an ambition to alter existing mindsets about belongingness, social cohesion, and equity (does the country have a childcare profession?). We show how childcare frontlines in two diverse political and cultural policy traditions became structured by similar ideas of pedagogy and child development and how childcare policy became part of important civilising processes but also with cultural differences about how to teach children how to accept (their own and others) differences and their future experiences with respect to inequality and difference.

Although we do not have the intention to empirical generalise the findings, the study adds to the current literature by showing a complex perspective about the role of childcare in our societies. As the findings suggest, we can observe an aspect of the state role in the civilising process through an exploration of pedagogy in ECEC institutions. However, in addition to simply concluding that we found similar educational content and use of childcare, we also saw how the composition of educational content varied in the two countries, reflecting complicated historical relationships between democratic developments and the civilising processes involving children and institutionalised childcare arrangements. The state role in civilising children became evident as differences in policy intentions about what was meant by equality, inclusion, and diversity as well as the differences. In Denmark, barriers were identified as special needs at an individual child level, and in Brazil, barriers were associated with a relationship between equity and social group belonging.

While previous studies showed how childcare is designed to solve families’ issues (e.g., Campbell-Barr and Coakley, Reference Campbell-Barr and Coakley2014; Prentice and White, Reference Prentice and White2019; Windebank, Reference Windebank2017), our research shows another perspective. The comparison revealed that in both settings, the state role in civilising childcare was expressed in dual policy intentions between intending progressive social change and at the same time seeking to preserve the existing social order. We see this as related to how childcare is expected to solve two contrasting problems: strengthening social cohesion while at the same time challenging its foundation (Fraiss et al., Reference Fraisse, Andreotti and Sabatinelli2004: 19).

Here, the study provides evidence of the frontline of the state as an important dimension in (re)producing social cohesion, which can inspire future studies. On the one hand, this is surprising given the different country contexts and, on the other hand, not so since raising a child is a human condition calling for very universal activities with necessarily similar characteristics. In all countries, it takes more than a village to raise a child, just as every child must learn and develop shared traits and skills in self-discipline to master the difficult task of belonging to and making sense in an abstract national group.

There are two exceptions to that generalisation: explorations of relationships between the family and the state (for an overview, see Daly chapter 9 in Castles et al., Reference Castles, Leibfried, Lewis, Obinger and Pierson2010) and social investment theory. Some of the work on the former gives attention to defamiliarisation, notably Van Lancker et al. (Reference Van Lancker and Ghysels2016), which has been argued to be important for the explanation of public social policy in Southern Europe, a source of cultural influences on Brazil. But this work has given little attention to ECEC. Social investment theory (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen2002; Taylor-Gooby, Reference Taylor-Gooby2004; Hemerijk, Reference Hemerijck2015) seems perhaps more relevant. It has been noted earlier that the most important academic comparative work on ECEC comes from that perspective (Bonoli, Reference Bonoli2013).

Neither defamiliarisation theory (see Yerkes and Javornik, Reference Yerkes and Javornik2019) nor social investment theory (see Saraceto, Reference Saraceno2015) offers scope for the development of comparative hypotheses about ECEC. Moreover, in the cases of Brazil and Denmark, what is interesting is, as has been shown before, the relative similarity of public policy development. Hence, a study of detailed practice at the local level, to be reported in (at the time of writing) future papers about this project, is better served at this stage by interpretative approaches as opposed to the testing of generalisations from comparative theory. In that respect, the two bodies of work discussed earlier in the article – on the civilising process and on the case for social pedagogy – offer an important approach for comparing the civilising aspects of (any) social policy. This discussion has been framed by a recognition that ECEC is a complex task, intended to go beyond simple child minding to engage in the civilising of children. As such, it contributes not just to the substantive issue, the complexity of the civilising process, but also to comparative studies. If the civilisation process is universal, then can it be examined comparatively? The answer would be yes, but with difficulty. A major issue concerns differences in the role of the state in that process. ECEC is not alone as a policy area where there are evident similarities across nations. In that respect, this article suggests that interpretive studies are needed to enable understanding of the subtle ways in which very similar national policies matter and why. However, we are aware of the difficulties of conducting such comparisons and taking the context into account. We are also aware of the limitations of studying official documents and guidelines. What is reported here is based upon official documents, making it hard to determine the extent of this to real-life practice. Much will depend upon discretions at various points via local governments to the kindergartens. To advance the understanding of state role in civilising childcare, such practices are being examined in a more detailed study zooming in on how the task of childcare is carried out in practice and with what consequences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Geert Bouckaert, Mark Considine, Fritz Sager, Eva Thomann, Nadine Raaphorst, and members of the WISER research group at Aalborg University for constructive comments that have helped us develop and improve the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research was funded partly by VIA University College, Denmark; the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (Brasil – CAPES – Finance Code 001); the São Paulo Research Foundation (Brasil – FAPESP – Grant/Award numbers 2013/07616–7, 2017/24750–0, 2019/13439–7, 2019/24495–5 2020/15430–4); and CNPQ (Brasil – Grant/Award Number: 305180/2018–5) Getulio Vargas Foundation, Brazil.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

APPENDIX: CODING FRAME