‘In short, an oasis is like an island of arable land floating in the desert.’

(‘要するに、オアシスは沙漠に浮かぶ島であり、可耕地である’)Footnote 1

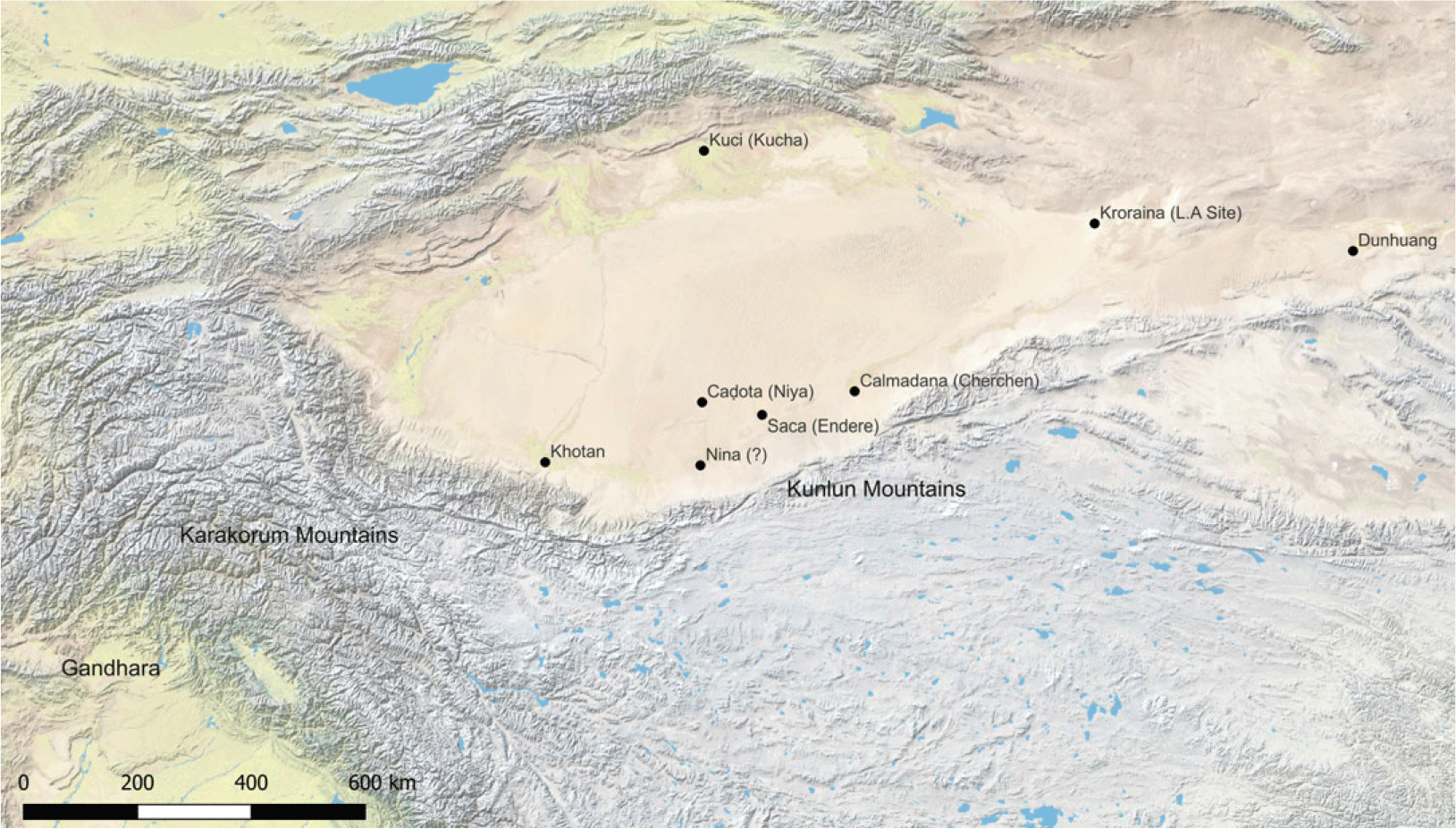

With this metaphor Hisao Matsuda starts his discussion of Inner Asian oases-polities and their people in his thought-provoking work Historical and Geographical Research on the Ancient Tianshan from 1970. It is an apt one, as these oases, which Matsuda further describes as laying strung like beads on a rosary along the feet of the great mountain ranges of Inner Asia, are surrounded by some of the harshest and most inhospitable wastelands on earth. The near insurmountable peaks of the Tian Shan, Pamir, Karakorum, and Kunlun ranges surround the region on almost all sides, while wastelands such as the vast Taklamakan desert permeate it. Matsuda, in his island metaphor, seeks to emphasize the isolation of these oasis-settlements and how their natural conditions limited their development. But he also turns this argument around, pointing out that precisely because of the limited resources available in each oasis the growing polities of the region were reliant upon contact and exchange from an early period. He then goes on to propose that these early contacts between smaller oasis-settlements throughout Inner Asia in time would grow into larger networks of exchange, networks that would eventually span across Asia connecting Iran and India in the west, and China and Mongolia in the east. Indeed, Matsuda suggests that the essential connections between these oases provides the foundation of trans-Eurasian contact and exchange, Footnote 2 a phenomenon commonly known as the Silk Road.Footnote 3

Matsuda’s theory does not, however, match the predominant conception about what drove contact and exchange across ancient Eurasia. For the history of the Silk Road studies has been, since its inception, a narrative dominated by empires. The first European scholars and explorers writing about the Silk Road, such as Sven Hedin and Sir Aurel Stein, were primarily interested in connections between the antique civilizations of the east and the west, and the great empires of Rome and Han. This should hardly come as a surprise, for not only were these early scholars schooled in a classical tradition, but they were themselves living in a time dominated by empires and imperialism.Footnote 4 Nor was this emphasis on empires unique to the early field of Silk Road studies. Rather, it was part of a larger trend, as touched upon in other articles of this Special Issue (SI), of scholarship which viewed long-distance contact in antiquity as driven by empires, with a strong emphasis on power differentials. As highlighted by Jeremy Simmons and Matthew Cobb, for example (see this SI), much of the early literature on the ancient Indian Ocean trade cast the Roman empire as the dominant actor on an economically primitive Indian subcontinent.

A similar outlook has informed what we might call the ‘traditional’ narrative for the Silk Road in antiquity. In this traditional narrative of empires, the start of Silk Road contact and exchange is usually connected with the journeys of the Chinese emissary Zhang Qian (張騫), as described in the Shiji (史記). In his travels, he is said to have brought back knowledge of distant regions which led to the Former Han empire’s expansion into Central Asia in the first century BCE. This expansion coincided with the expansion of other major antique empires such as the Parthian empire and later the Kushan empire, both thought of as important ‘middlemen’ on the Silk Road. Even more important, however, was the rise of the Roman Empire, which is regarded as providing a major market for Chinese silk. Thus, trade flourished during the Former Han dynasty (206 BCE-9 CE), briefly falling into decline during the Wang Mang Interregnum, and then flourishing once again during the Later Han (25-220 CE). The trade is then usually thought to have almost disappeared by the third century, coinciding with the decline of the Han, Kushan, and Parthian empires. This period of decline signalled the end of the first ‘Silk Road Era’, to borrow Craig Benjamin’s term, and this lull in trade would last until the ‘Golden Age’ of the Silk Road under the Tang dynasty (618-907 CE) in the seventh and eighth centuries. As such, both periods of prosperity and decline are regarded as intersecting with the dominance (or lack thereof) of empires in Eastern and Central Asia.Footnote 5

A glance across the shelf of major publications concerning the Silk Road in antiquity from the past two decades will show that this narrative of empires remains important. In the past two decades, major works have carried titles such as Empires of the Silk Road, Footnote 6 The Roman Empire and the Silk Routes,Footnote 7 or Empires of Ancient Eurasia.Footnote 8 Similarly, recent edited volumes addressing the topic have carried titles such as Between Rome and China,Footnote 9 Eurasian Empires in Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages,Footnote 10 or Empires and Exchanges in Eurasian Late Antiquity.Footnote 11 Even perusing volumes such as Xinru Liu’s The Silk Road in World History, for example, one will find that these works too tend to focus upon the role of empires. Liu’s book starts with two chapters entitled ‘China Looks West’ and ‘Rome Looks East’.Footnote 12 The narrative of empires, particularly Chinese empires, as the predominant actors also remains a hallmark of much Chinese scholarship on Inner Asia and the Silk Road. A telling example is Junshi Ye’s recent study of the polities of the Niya oasis, in which he attributes the development and prosperity of the oasis community primarily to the function of the Silk Road and Chinese influence, and notes that ‘all these were mainly based on the Central Plains’ control of the Western Regions’.Footnote 13 Another recent example can be found in the “series foreword” to the English language version of the Silk Road Research Series, where Xinjiang Rong, one of the leading scholars in the field, casts the Silk Road as a story of contact between Eastern and Western civilizations.Footnote 14 His article in the second volume of the series goes on to describe the development of the Silk Road as predominantly driven by empires, very much in the vain of the traditional narrative sketched out above.Footnote 15 As such it would be fair to say that the Silk Road is still seen as a phenomenon predominantly initiated by and reliant upon empires.

In the field of world history, these types of empire-centric narratives have increasingly been challenged by new research, as outlined in Matthew Cobb’s introduction to this SI. Much of this has come as part of a post-colonial critique of the earlier narratives, but other new theoretical frameworks have come to the fore, including globalization and glocalization thinking (which have sought to go beyond older models, like World Systems Theory).Footnote 16 Much of the debate within Silk Road studies has seen a similar turn, indeed even represented by some of the titles quoted above. For one, the role played by Sogdian people on the Silk Road has increasingly been recognized and gradually extended beyond their most active periods in the seventh and eighth centuries. Indeed, Xinjiang Rong’s article argues very persuasively that the role of the Sogdians as important actors on the Silk Road must be extended back to the third and fourth centuries. Yet, the most notable trend in the past few decades of Silk Road studies has been to stress the importance of the nomadic people of Inner Asia, and their polities and social structures, in both conducting and driving exchange. This has been particularly strongly argued by Christopher Beckwith in Empires of Ancient Eurasia, mentioned above. In it he emphasizes the political structures of nomadic empires as important drivers of exchange, with rulers seeking gifts through trade for their warrior retinues, and argues that the classical empires of Han and Rome were a disruptive, rather than a driving, force in Eurasian trade.Footnote 17 Some of these ideas have gained traction with and been incorporated into the more traditional narratives of the Silk Road, as seen most clearly in the recent work of Craig Benjamin.Footnote 18 A number of archaeologists, such as Ursula Brosseder,Footnote 19 Michael Frachetti,Footnote 20 and William Honeychurch,Footnote 21 have similarly focused on the nomadic people of Inner Asia, but have taken a slightly different approach, emphasizing networks. This network-oriented approach in archaeology argues that it is in the interaction of different groups that the key to understanding trans-Eurasian interaction and trade in the prehistoric and early historic period can be found.

Few authors have, however, approached the Silk Road phenomenon through the theoretical framework of Global History, despite the Silk Road frequently being invoked as a form of ancient globalization. To be sure, some authors, such as Benjamin, have touched upon the connection between the antique Silk Road and globalization, but he does so only briefly.Footnote 22 I argue here that a global historical perspective has much to offer the study of the Silk Road and can serve as a powerful corrective of the traditional and still predominant empire-centric narrative. This is partly because many strands of Global History, in particularly those concerned with large-scale system-building, be it the formation of empires or of trade systems, have long emphasized networks and network thinking.Footnote 23 Such an approach is particularly apt when dealing with a phenomenon such as the Silk Roads, as shown also by the network approach within ‘Silk Road’ archaeology. It envisions this trade network not as a road between two empires but as a network with multiple nodes, and potentially multiple centres and actors. The emphasis on the interplay between the global and the local that forms the focus of globalization and glocalization thinking, is also a perspective that is very relevant to Global History. It requires us to not only acknowledge local agency and identify how global phenomena grew out of local conditions, but also to keep the wider ‘global’ picture in mind, emphasizing how local societies reacted to external stimuli. These two perspectives, as I will endeavour to show, are very useful when working with the Silk Road phenomena, as rather than framing empires as the sole driver of contact and exchange these perspectives tend to emphasize the interplay between multiple different factors, from empires and polities down to groups of local elites or merchants.

Drawing upon both network thinking and perspectives from Global History, this article will, inspired by Matsuda’s hypothesis, attempt to look at a group of potential actors on the Silk Road who have thus far garnered only modest attention, namely the settled oases-polities of Inner Asia. Based on the findings of this article, I will argue that Matsuda’s assertion appears to be correct and that these oases-polities played an active role in exchange stretching from India to China, being crucial in both facilitating and sustaining these networks. In order to achieve this, a case study on the kingdom of Kroraina is presented here, a polity that ruled much of the south-eastern Tarim Basin from the second to at least the fourth century CE. This is an interesting case for analysis, not only because of the richness of the sources, but because it falls into a period commonly seen as a low point of Silk Road activity. The first part of the case study will therefore start by addressing this negative evaluation of the third and fourth centuries, by looking at the evidence for trade as seen in both tombs and written documents. The second part will look at how the imported goods evident in these sources might have made it to Kroraina, discussing both their provenance and the evidence for merchants travelling through the kingdom. Finally, the role the kingdom itself played in creating and maintaining these networks will be considered, focusing on solutions the kingdom provided to the fundamental problems of travel through the Tarim Basin. However, before presenting the case study proper, a short introduction to the kingdom of Kroraina is in order.

The kingdom of Kroraina

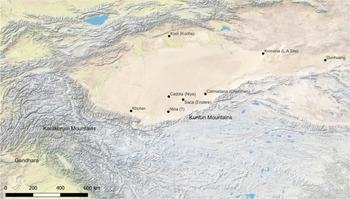

The ruins of the kingdom of Kroraina were originally brought to scholarly attention following the journeys of European explorers through the Tarim Basin around the turn of the twentieth century. Sven Hedin, while studying the hydrography of the Tarim river and seeking its terminal lake, first came upon a number of ruins north of the dried-up lake Lop Nur in early 1900 (See Figure 1 for an overview of the Krorainan sites).Footnote 24 He conducted some limited exploration of the site and uncovered some documents, but it would be the British-Hungarian Sir Aurel Stein who would discover and excavate most of the material from the Krorainan sites. In the span of a series of three expeditions between 1900-1916 he discovered and excavated four major sites associated with the kingdom of Kroraina, namely the Niya (Caḍota), Endere (Saca), Miran, and Lop (Kroraina) sites.Footnote 25 In the century since Stein’s exploration a number of Chinese teams have conducted smaller expeditions to the various sites, including some smaller excavations. But no major work was conducted before 1988 when a Sino-Japanese team started conducting large scale excavations at the Niya site, a project which ended in 1997.Footnote 26 Due to the extraordinary conditions for preservation prevalent in the region, one of the driest on earth, the sites yielded a large number of often nearly intact structures, a number of fortifications, at least one stupa per site, as well as a large number of graves with extremely well-preserved contents. Even more important for our purposes, however, are the over thousand written documents, on wood, silk, hide and paper, which the sites yielded.

In the main, the sites that once made up the kingdom of Kroraina yielded documents in two different languages and scripts. One of these bodies of documents is in Chinese using Chinese characters; the other a form of Gandhari Prakrit written with the Kharosthi script. The former includes 830 documents and fragments, the vast majority of which were found at the Lop site and which were the product of the administration of a Chinese garrison posted there by the Wei and the Jin dynasties. Several of these documents are dated, spanning from 264 to 330 CE.Footnote 27 Even more interesting, however, are the Kharosthi documents written in a local variety of Gandhari Prakrit, a script and language originating from northern India. These documents, of which 880 have been found to date, were primarily found at the Niya site, several even found ordered in their original archives, though both Endere and Lop also yielded a number of Kharoshti documents. They were for the most part the product of the royal administration of the local kingdom, though amongst them were also contracts, legal rulings, inventory lists, and private letters. The Kharosthi documents were dated using the regnal year of the local kings, but as they were in some cases found together with dated Chinese documents, and based on known events recorded in Chinese histories, John Brough was able to convincingly anchor the local reckoning and date them to the third and fourth century CE.Footnote 28

As described in the standard histories of the Han dynasty, the kingdom of Kroraina was originally a small oases-polity in the area around Lop Nur, known as Loulan (樓蘭) and later as Shanshan (鄯善) in Chinese.Footnote 29 As described by the Hou Hanshu (後漢書) this kingdom, in the first and second century CE grew and conquered a number of surrounding kingdoms, becoming one of two major kingdoms in the southern Tarim Basin together with Khotan to the west.Footnote 30 Thus, by the third century the kingdom, as encountered in the Kharoshti sources, stretched from Lop Nur in the east to the Niya river in the west, as seen in document n.14:

Wedge Cov.-tablet. Obv.

To be given to the cozbo Bhimaya (or Tsimaya) and ṣoṭhaṃga Lýipeya

Wedge Under-tablet. Obv.

His majesty the king writes, he instructs cozbo Bhimaya and ṣoṭhaṃga Lýipeya as follows: Ṣameka informs us that he went as an envoy to Khotan. From Calmadana they gave him a guard (valag̱a) and he went as far as Saca. From Saca they gave him a guard and he went as far as Nina. From Nina to Khotan a guard should have been provided from Caḍota. As far as Khotan […….]. When this sealed wedge-tablet reaches you, the hire of a guard from Nina to Khotan is to be handed over according as it was formerly paid, along with an extra sum. A decision is to be made according to the law.

Wedge Under-tablet. Rev.

Of ṢamekaFootnote 31

This typical Krorainan royal order, which takes the form of two wooden tablets placed together to form a sealable document, gives the major oases of the kingdom westwards from the capital of Kroraina as Calmadana (Cherchen), Saca (Endere), and Caḍota (Niya). Each of these oases was the centre of a province called a raja, a name that might indicate their former independence, and from them were governed various smaller sites such as Nina (modern Niya) on behalf of the king of Kroraina, usually through an appointed cozbo.Footnote 32

From this quick overview one can already see that Matsuda’s suggestion that the Tarim Basin oases were closely enmeshed within networks of contact appears to hold true, and many of the documents show how people and resources, especially in the form of tax, moved between the different oases of the kingdom.Footnote 33 Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the routes through Kroraina, as described in the Krorainan material, match very closely the westwards itineraries given in Chinese histories, itineraries that are regularly taken as the path followed by the Silk Road. Beginning with the Hanshu (漢書) there are said to be two routes, later amended to three, through the ‘Western Regions’. According to the Hanshu the southernmost of these routes went by way of the kingdom of Shanshan (Kroraina), skirting the northern rim of the southern mountains.Footnote 34 Later, in the parts dealing with individual kingdoms, this route is described as running past Shanshan (Kroraina), Qiemo (Calmadana), Xiaoyuan (uncertain), and Jingjue (Caḍota).Footnote 35 The same list is also repeated in the Weilue (魏略) section on the ‘People of the West’ preserved in a footnote of the Sanguozhi (三國志) from the third century.Footnote 36 The similarities here are striking, suggesting that the routes travelled by Chinese envoys and soldiers at the time of the Han and Wei dynasties were the same as those utilized by the local population.Footnote 37

And yet despite the richness of the Krorainan sources they have rarely been included in wider Silk Road narratives, nor in broader discussions of the region in antiquity. That is of course not to say that no scholarly works exist on this body of material. On the contrary, a large effort has gone into deciphering, dating, and categorizing the Krorainan material.Footnote 38 Much has been written on specific aspects of the kingdom, such as the location of its capital, its socio-political structure and its relationship with surrounding empires, whether the Chinese or the Kushan.Footnote 39 Specific sides of the Krorainan sources have also been seen in larger contexts, and in particular its art with its clear parallels to western traditions have garnered much interest, particularly with a comparative perspective in mind.Footnote 40 Yet rarely has the evidence from Kroraina been considered in broader discussions of the Silk Road and long-distance trade in antiquity. In fact, the only major English language work on the Silk Road to explore the Krorainan material is Valerie Hansen’s 2012 The Silk Road: A New History, which looks in detail at a number of central Asian sources.Footnote 41

The consumption of imported goods by Krorainan elites

In her chapter on Kroraina, Hansen discuss various aspects of the Krorainan society in detail, including its economy and trade. She describes its economic activity as being based on subsistence and further suggests that there is practically no evidence for merchants, trade, or profit-seeking ventures in the sources. To support this view she points to the very limited use of money in the sources and in particular she stresses the fact that in all the Kharosthi documents there is only a single instance of the word ‘merchant’ (vaniye) being used.Footnote 42 This last point is certainly a little problematic, being an argument ex silentio, and one which, upon closer inspection of the sources, might be questioned (this is discussed further in the next section). But in making this major assertion Hansen also misses one important point. For while there might be only a single merchant mentioned in the documents, this overlooks the fact that in the Krorainan sources there is a plethora of evidence, both archaeological and from written documents, to suggest that goods from distant regions reached Kroraina with some regularity. Given the constraints of this article a full survey of all these instances of imported goods will not be possible, but in the following discussion I critically evaluate two of the most telling sources, namely the finds from tomb 95MN1M3 and the inventory given in document n.566.

Tomb 95MN1M3 was only one of a number of tombs uncovered by the Sino-Japanese archaeological team during their excavation of the Niya (Caḍota) site. Several cemeteries were found throughout the former oasis, with 95MN1 as the largest find on a hill in the northernmost part of the site. The excavated area of 95MN1 contains nine tombs of two distinct types labelled boat-shaped and box-shaped graves in the excavation report.Footnote 43 M3 is of the box-shaped type, which represented the largest graves, and contained the body of a man and a woman with a rich assemblage (See Figure 2). In addition to food, wooden trays and cups, weapons for the man and some likely local woollen textiles, the tomb contained a veritable hoard of imported goods.Footnote 44 Most striking of these are the clothing and bedding with which the deceased were buried, as these were almost entirely made out of silk with some cotton and only one woollen piece. In total the tomb contained seventeen items either wholly or partly made out of silk, including kaftan-like jackets, pants, mittens, shoes, hats, and a belt, as well as large amounts of silk scraps and even silk thread on a spindle amongst the woman’s goods. As seen in Figure 2, much of this silk was also of a very high quality, worked with vibrant polychrome patterns and many also including Chinese characters forming blessings and well-wishes.Footnote 45

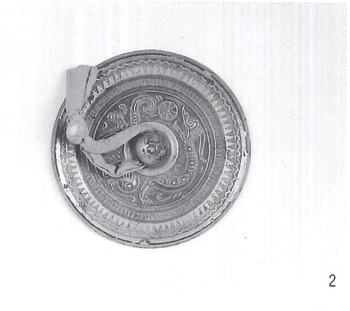

Further items with a likely Chinese provenance include a lacquerware box placed above the head of the woman. In this had been put several items associated with female activities, such as pieces of silk cloth and the spindle with thread. It also contained articles of personal grooming such as a bamboo comb and two small, sealed silk pouches containing small clumps of organic material which the excavators suggested might have been scented. Finally, it held a very fine bronze mirror with a coiling dragon design, seen in Figure 3, strongly reminiscent in style of mirrors from the Later Han period; this was contained in a silk pouch.Footnote 46

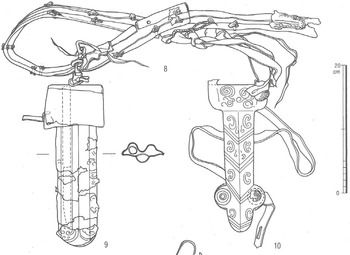

The man too had personal articles that had either been imported or drew upon foreign designs. Notably, the sheath for his short sword is easily recognizable as belonging to the so-called ‘four-lobed’ style (See Figure 4).Footnote 47 As shown by Brosseder, this type of sheath, usually used for daggers, was widespread across Inner Eurasia throughout antiquity, with the most famous examples being the spectacular gilded short sword sheath from Tilliya Tepe in AfghanistanFootnote 48 and the sheath depicted on the frescos of king Antiochos I of Commagene at Mount Nemrut.Footnote 49

Finally, both the man and the woman had been buried with jewellery. The majority of this consisted of beads made of either glass, stone, or silk, but two items in particular stand out as they incorporated pearls. The first was a fine golden ear ornament, worn by the woman, which had four small strings of pearls hanging from it. The second was the woman’s necklace, seen in Figure 5, which primarily consisted of red silk beads, but which incorporated a string of twenty small pearls as well.Footnote 50

Thus, we can see the wealth possessed by members of the Krorainan elite at the time of the burials in 95MN1, with similar assemblages present in both other box-shaped graves and to a lesser extent amongst the boat-shaped graves of the site.Footnote 51 Unfortunately, the dates for these graves remain tentative, but almost certainly they fall within the first few centuries CE. The excavation team dated the tomb 95MN1M3 to around the second century, based on the patterns on the Chinese-made silk brocade and mirror that were in a style common to the Later Han Dynasty.Footnote 52 But this of course only gives a terminus post quem. However, since tomb 95MN1M8, which was found in a lower layer directly below M3, contains strips of silk with writing in Kharosthi, it is equally possible that the graves might date from the third or even the fourth century, i.e. closer in time to most of the Kharosthi documents.Footnote 53 Subsequent radiocarbon dating of the graves has given a range around 200 CE; thus, it seems reasonable to place the graves in the late second or early third century CE.Footnote 54

Even if dated to slightly earlier, it appears that the wealth and taste for foreign goods amongst the Krorainan elites had changed little in the intervening century, for in document n.566 are listed many of the very items present in the grave M3. The document contains a command from the royal court to the local official, and concerns the theft of a number of valuable items:

Wedge Under-tablet. Obv.

His majesty the king writes, he instructs the cozbo Taṃjaka as follows: Kupṣuta and Tilutamaae inform us that they have lost seven strings of pearls (mutilata), one mirror, a lastug̱a made of many coloured silk, and a suḍ̱i ear ornament. The tsaṃghina Mosdhaya, when apprehended before the magistrates spoke thus: It is true that I stole these objects from Kupṣuta and Tilutamaae. I sold them to Konumae. I have received no payment. When this sealed wedge-tablet, etc.

Wedge Under-tablet. Rev.

Of Tilutamae and Kupṣuta.Footnote 55

Exactly what is meant by a lastug̱a, beyond a basic understanding that it represents an article of clothing, or a suḍ̱i ear ornament, is not known.Footnote 56 But despite this, the similarities between the items listed as stolen and those found in the grave M3 are striking. The strings of pearls, for example, very likely refer to a small, ornamental pieces worn by the woman in the grave M3 and the mirror was probably of the same type, if not the same quality, as that which she possessed. The silken lastug̱a too likely represent one of the many articles of clothing or decoration from grave M3. More specifically, they may be one of the smaller pieces like the mittens, belt, or pouches, because in four of the letters from Caḍota lastug̱as were sent as tokens or small gifts along with the letter, suggesting that it was a small object (see documents n.161, 184, 288, 585). Tilutamae’s suḍ̱i ear ornament is more difficult to identify, though it could well have been something similar to the gold and pearl ornament worn by the woman of tomb M3.

The similarities between tomb M3 and the letter n.566 are remarkable, and though neither Kupṣuta nor Tilutamae carried titles, one must assume that they were a couple of some standing within Krorainan society to possess such a rich inventory. Yet document n.566 is far from the only one that describes such rich inventories of stolen or lost goods. In document n.149, for example, a man, who is said to be a fugitive or refugee (palayaṃnag̱a), complained that a large inventory of clothing, including what is termed Chinese robes (ciṃna cimara), a silver necklace and a sum of money, had been taken from him.Footnote 57 Even more impressive are the lists of items claimed stolen by Larsu, son of a ranking official and himself later a cozbo official (see documents n.318 and n.345). Of these the first document is especially noteworthy, as it lists some ten items of clothing, most of them polychrome and some made of silk, in addition to several ornamental items in gold.Footnote 58 Taken together with the finds from the graves, and the many more examples of prestige goods mentioned for example as gifts in the Kharosthi documents, these examples show that quite significant amounts of prestige goods circulated amongst, and was consumed by, the Krorainan elites.

Evidence for trade in Kroraina

It is clear that the local Krorainan elites of the second to fourth centuries took part in a wider world of conspicuous consumption, drawing upon materials, such as silk and corals, or designs such as the four-lobed dagger sheath, whose origins lay beyond the Tarim Basin itself. This should by itself dispel the notion of an isolated oases kingdom and encourage us to reconsider the traditional evaluation of the third and fourth centuries as a period of political and economic collapse along the Silk Road.

But what can be known of the provenance of these items? The sword sheath found in M3 for example clearly drew on a design common across Eurasia, though being made of painted and lacquered wood it could just as easily have been the product of a Krorainan craftsman. Similarly, some of the silk might have been produced locally, and though the extent to which this happened is still up for debate, it is at least clear that people in the Tarim Basin both unravelled and spun new silk fabric.Footnote 59 Similar arguments could also be made for many of the bronze mirrors uncovered, or for most of the beads, which could well be either local products, reproductions, or imitations. As noted earlier, Hansen stressed that there is but a single use of the word for ‘merchant’ in the more than 800 Kharosthi documents from Kroraina.Footnote 60 Thus, if indeed imported, how then did these goods make it to Kroraina, given this apparent lack of merchants and trade?

These are not questions that can be exhaustively treated in this one article, and there are likely a number of factors which should be considered when seeking to answer this question. It is important, for example, to take into account factors like Kroraina’s political connections and connections created by the local Buddhist communities. Yet when considering trade, there are at least two types of goods of particular interest from M3 and document n.566, not only because they must have been imported from distant regions but also because they speak to the wide and diverse nature of trade connections through the south-eastern Tarim Basin in antiquity. Thus, the following section will discuss the connections evident in the patterned, polychrome silk used in Krorainan clothing, and the many pearls, corals’ and cowries used in Krorainan ornaments.

Chinese silk and Chinese merchants

Dealing first with silk, there is, as noted, some disagreement as to when local silk production might have started in the southern Tarim Basin. Silk was certainly well-known and widely used in Kroraina by the third century, being the third most common type of textile in the written sources—after (woollen) rugs and felt—and the most commonly used textile in the 95MN1 graves.Footnote 61 Studies of textile finds, originating from the Niya and the Yingpan sites,Footnote 62 have furthermore suggested that some of the silk could have been made locally, and that Chinese weaving techniques were spreading in the region.Footnote 63 As previously observed, these studies have shown that the local population unravelled silk textiles only to spin them again in patterns more to their liking. Yet as stressed by de la Vaissière there is no mention of silk production, nor silk worms, or even mulberry, discernible in the written sources from Kroraina.Footnote 64 Thus, whether some of the silk from graves like M3 might have been produced, or at least woven, locally is difficult to determine.

But at least for much of the patterned, polychrome pieces, their provenance was certainly Chinese. This is suggested by the designs and patterns used, designs that drew upon Chinese mythology and symbolism. The woman’s shirt from M3 for example depicted various animals including tigers, lions, leopards, and peafowls: all creatures not otherwise depicted in Kroraina nor native to the region. It also depicts dragons, the quintessential mystical beasts in Chinese tradition.Footnote 65 Even more telling is the inclusion of a wealth of Chinese characters, most forming well-wishes and blessings. The woman’s pants for example carried a repeated, stitched inscription of ‘長楽大明光’, wishing ‘long-lasting joy, bright and shining’.Footnote 66 As shown by Tseng, one of the inscriptions from tomb M8, directly below M3, even carried references to auspicious events recorded in Chinese histories.Footnote 67 Finally the weaving technique of some of the pieces are noteworthy, as they utilized special techniques known to have originated in China. This is seen for example in the man of M3’s inner cotton shirt which had a piece of very fine silk attached, made with a complex compound tabby. As discussed by Angela Sheng, these types of warp-faced compound tabby weave would have required techniques and tools not evident in Kroraina.Footnote 68 Consequently, given these technical requirements, the use of the Chinese language, the textual references, and how heavily many of the patterns and designs drew upon Chinese tradition it seems highly likely, as similarly concluded by Hansen and Feng, that the majority of the patterned, polychrome silk in Kroraina had been produced in China.Footnote 69

But how did these move from the Chinese heartlands to the distant kingdom of Kroraina? It is likely that some of these especially fine pieces had reached Kroraina through political connections, perhaps as gifts from the Chinese empire to local rulers or elites. The Chinese garrison at the capital was similarly a plausible source of silk entering into the local economy, as record slips show that the garrison acquired and stored quite large volumes of silk.Footnote 70 In one case (the slip n.102) the silk was used to buy grain, presumably from the local population, though as only this one case exists the extent of this military-trade is hard to determine. But both the Kharosthi documents and the Chinese documents from Kroraina show that silk was also traded by private individuals through the region, with Chinese merchants presumably playing an important role. This is certainly how document n.35 has been typically interpreted, the one document that makes mention of merchants in the Kharosthi collection. The document, which is only the cover-tablet of a larger double-wedge document, has the form of a royal command and deals with a debt in silk:

Cov.-tablet. Obv.

To be given to the cozbo Bhimaya and sothamga Lyipe

Cov.-tablet. Rev.

Suḡ̱ita is to be prevented. At present there are no merchants from China, so that the debt of silk is not to be investigated now. As regards the matter of the camel Taṃcina is to be pestered. When the merchants arrive from China, the debt of silk is to be investigated. If there is a dispute, there will be a decision in our presence in the royal court.Footnote 71

Most authors who have touched upon this very interesting document have taken the merchants in question to be Chinese, and used it to argue that the local population were unfamiliar with silk and its value.Footnote 72 This is a problematic conclusion for a number of reasons, overlooking both the wealth of silk evidently in Kroraina, the fragmented nature of the document and the fact that the document does not give the merchants as Chinese but rather notes that they will arrive from China.Footnote 73 The merchants in question might have been Sogdian, as suggested by Xinjiang Rong, or might just as well have been Krorainans, as the only Kharosthi document to mention an exchange conducted in silk was in fact one conducted by a Krorainan.Footnote 74 This man, also named Suḡ̱ita, is in document n.3 recorded as having bought a female slave and paying with forty-one rolls of silk. One must wonder if the Suḡ̱itas in these two documents is in fact the same man, given that the documents were found together. One can speculate that he was a local merchant dealing in silk, or else a wealthy local. But given the fragmented nature of document n.35 it is in truth impossible to tell. What document n.35 does show, however, is that merchants, whether Chinese, Krorainan, or otherwise, moved between China and the Caḍota oasis.

No further mention of merchants is made in the Kharosthi documents, though several individuals said to be Chinese do appear (see documents n.80, 255, 324, 686, and 748). But the Chinese documents from Kroraina contain two very interesting cases, namely the paper documents n.6,1 and n.13,2 from Hedin’s collection.Footnote 75 Both documents are letters and mention a man surnamed Ma (馬): the addressee of n.6,1 is called Ma Ping (馬評), while n.13,2 makes mention of a Ma Li (馬厲). These two men appear in a number of other letters and documents, and one could speculate they may have been related, though this cannot be conclusively proven. Both were, however, in several documents involved in trade, with both n.6,1 and n.13,2 mentioning the buying and selling of silk. Document n.6,1 is particularly remarkable, as it not only appears to deal with simple exchange but also discusses the intricacies of price and trade. After two fragmented lines discussing silk and furs it reads: ‘When you come to the eastern district, sell. Now you buy in the commandery coloured silk at a reasonable price, it stands in 10.’Footnote 76 It goes on to discuss what is to be done with the silk, as well as a debt which is to be retrieved. As this shows, Ma Ping and his associates not only acquired silk in the Dunhuang region, which is likely what the commandery refers to, but also that they were aware of price fluctuations and attempted to buy at a good price. Document n.13,2 similarly gives instructions on buying various types of silk and how to handle it. The relationship between these two men notwithstanding, these examples show that not only did silk move through political connections, but that coloured silk textiles were traded into and within the kingdom of Kroraina.

Indian Ocean goods and Sogdian merchants

As with silk, the pearls found and used in Kroraina should be taken as evidence of mercantile activity, as there can be no doubt about the distant provenance of the pearls found in grave M3 and document n.566. The Sino-Japanese team’s report does not provide a detailed analysis of the pearls from M3, nor does it suggest which species of mollusc they may have come from, but the source must almost certainly have been some warm and distant ocean. In fact, only two probable sources for these pearls existed in the period, namely the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. These are both known to have been sources of pearls in antiquity.Footnote 77 Nor were these pearls the only precious material from the ocean in circulation in Kroraina, for several cowries and more than fifty pieces of coral has also been found across the Krorainan sites.

The corals in particular are interesting as there is no indication of coral being harvested in China at this early time, with both the Hou Hanshu and the Weilue listing it amongst the products of the Roman Empire.Footnote 78 The Roman author Pliny the Elder (mid-first century CE) notes that coral was harvested both in the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea, though the best coral was found in the MediterraneanFootnote 79 and the text known as the Periplus Maris Erythraei (a mid-first century merchants guide) observe that pearls were sold in certain Indian ports.Footnote 80 Such a distant, Mediterranean origin for the corals at Kroraina would seem truly astonishing, but even corals and pearls from the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean would have had to travel vast distances before being worked by craftsmen in a relatively small Krorainan oasis.

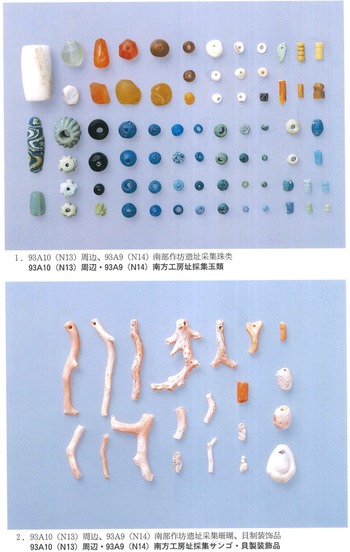

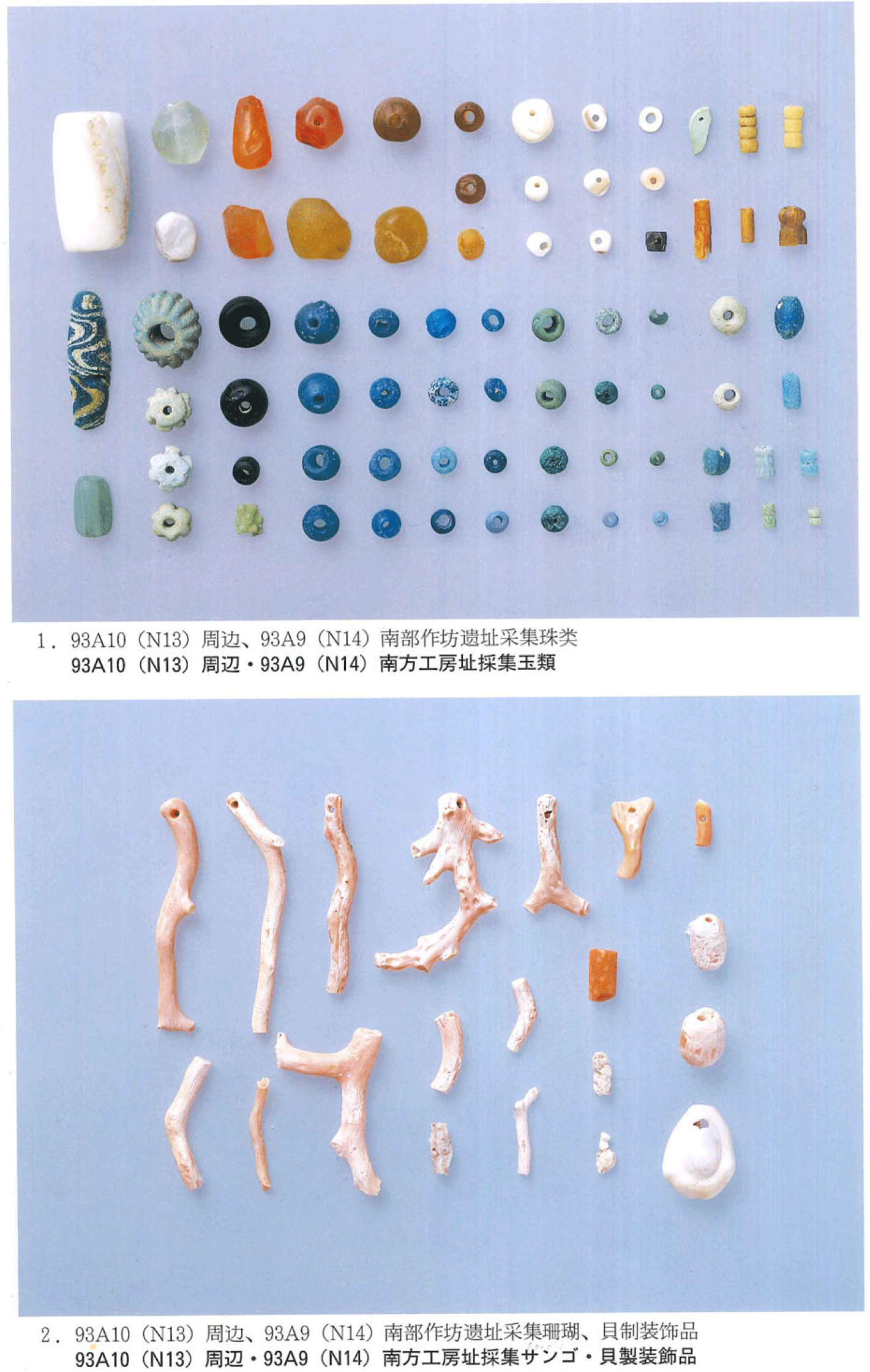

Although the material originated from far distant oceans, the archaeological finds show that many of the ornaments themselves were made in Kroraina, and that the pearls, cowries, and corals arrived as unworked materials. The most important sites in this regard are an area south of the ruin N14 (93A9), which the Sino-Japanese excavators termed the ‘southern workshops’ due to the great quantities of partly worked goods, as well as the four kilns, uncovered there.Footnote 81 As shown by Figure 6, these ruins yielded numerous beads and ornaments in a large variety of material and in various stages of processing. The coral, for example, ranged from small, worked beads with holes for threading and larger holed pieces for use as pendants, to raw unworked pieces. The fact that these exotic materials were worked and fashioned into objects locally is of crucial importance as it speaks volumes about the nature of Kroraina’s trade connections. These pearl or coral beads were not only brought to Kroraina as finished products, perhaps slowly carried through social exchanges or political connections, but were in fact arriving in large enough quantities that local craftsmen could store significant supplies. As many as twenty-two pieces of corals were found in the case of the ‘southern workshop’ and as many as thirty-one small pieces in ruin N.24 (92A9).Footnote 82

Figure 1. Map of inner Asia with sites of interest.

Figure 2. The corpses of M3 fully dressed. Images used courtesy of the Academic Research Organization for Niya, Bukkyo University, Japan.

Figure 3. Bronze mirror from M3 with dragon design. Images used courtesy of the Academic Research Organization for Niya, Bukkyo University, Japan.

Figure 4. Four-lobed sword sheath from M3. Images used courtesy of the Academic Research Organization for Niya, Bukkyo University, Japan.

Figure 5. Silk bead and pearl necklace from M3. Images used courtesy of the Academic Research Organization for Niya, Bukkyo University, Japan.

Figure 6. Beads, pearls, corals and cowries from ruins N.13 and N.14. Images used courtesy of the Academic Research Organization for Niya, Bukkyo University, Japan.

The frequency and the reliability of these trade connections are demonstrated even more clearly from the spices alluded to in the Krorainan sources. Although not present archaeologically, for obvious reasons, four documents mention spices, in three of the cases as gifts attached to letters (see documents n.77, 109, 354, and 702). The one exception to this, however, is the most interesting, being a list written on the reverse of letter n.702, though likely not connected to that text:Footnote 83

Rectangular Under-tablet. Rev.

[…….] 1 dhane, 3 dhane of pepper (marica), 1 drakhma of ginger, 2 drakhma of (long?) pepper (pipali), 1 dhane of tvaca (Cinnamon or Cassia), 1 dhane of small cardamoms (suṣmela), 4 stater of sugar (śakara).Footnote 84

Such a variety of spices present in one list clearly means it was more than a mere chance possession, but rather represented a household’s, or possibly a merchant’s, inventory. All these spices were, furthermore, the products of tropical regions far from dry Kroraina, and like the corals and pearls almost all of them probably originated in India. The weight measurements, as far as they are known, are small. But the fact that someone in Kroraina would draw up such a varied inventory of spices is telling, because unlike most of the imported goods discussed above spices are in their very nature meant to be consumed, or else they perish (some more quickly than others). This means that even small quantities must represent a relatively direct and rapid connection to their place of origin, rather than a slower, more gradual type of transfer which could have been the case with for example beads and pearls.

We see then that there is evidence for small quantities of very valuable goods being carried all the way from the Indian Ocean World to Kroraina with some regularity. But who might have carried these goods and through which connections? This is not readily apparent in the Kharosthi sources from Kroraina, though one important link which should be considered is the close connections between the kingdoms of Kroraina and its western neighbour, the kingdom of Khotan. Khotan appears regularly in the Kharosthi documents. Indeed, it is the second most frequently mentioned place name in all the written material. This is partly because most of the documents were found at Caḍota, the westernmost oasis of Kroraina and bordering Khotan, but it still speaks to Khotan’s importance. Most of the Krorainan sources that mention Khotan were political in nature, concerned with the passage of envoys (notably, n.14, 22, 86, 135, 214, 223, 248, 251, 253, 330, 362, 367, 388, 637, and 686), defence and security (n.272,283, 376, 516, and 625), or the conveying of news (n.248, 272, 283, and 578). A number of documents also mention Khotanese living or moving through Caḍota (n.30, 36, 216, 296, 322, 333, 335, 403, 471, 662, 517, and 735), and in two cases Caḍotans travelling to Khotan (n.400 and 584).

None of these documents describes trade between Khotan and Kroraina as such, though many of the travellers mentioned may well have conducted such activities. And there is one document, in particular, that describes an interesting connection in this regard, namely the unusual document n.661.

Oblong tablet. Obv.

On the 18th day of the 10th month of the 3rd year, at this time in the reign of the king of Khotan, the king of kings, Hinaza Deva Vijitasiṃha, at that time there is a man of the city called Khvarnarse. He speaks thus: There is a camel belonging to me. That camel carries a distinguishing mark, a mark branded on it, like this-- VA SO. Now I am selling this camel for a price of 8,000 maṣa to the suliḡa Vaḡiti Vadhaḡa. On behalf of that camel Vaḡiti Vadhaḡa paid the whole price in maṣa and Khvarnarse received it. The matter has been settled. From now on this camel has become the property of Vaḡiti Vadhaḡa, to do as he likes with it, to do everything he likes. Whoever at a future time complains, informs, or raises a dispute about this camel, for that he shall so pay the penalty as the law of the kingdom demands. By me Bahudhiva this document (?) was written at the request of Khvarnarse.

SPA SA NA

(RBS notes that these characters are written larger and with long stems, likely the initials of the witnesses below.)

(A line of Brahmi)

Nani Vadhaḡa, witness. Śaśivaka, witness. Spaniyaka, witness.

Oblong tablet. Rev.

(Various isolated aksaras, some of them apparently Brahmi)Footnote 85

Although found at the Endere (Saca) site in Kroraina, Burrow concluded that document n.661 was likely written at Khotan, as indicated not only by its content but also by the peculiarities of its script and dialect.Footnote 86 The date, given in the year of a king of Khotan, is not known. But de la Vaissiere has suggested that king Vijitasiṃha was the same as the king Simha found in the Tibetan text Li yul lunbstan-pa (Prophecy of the Li Country), which he suggests would have reigned around 320 CE.Footnote 87 Given that the document was found together with Kharosthi documents of the same types as those found across Kroraina, this conclusion seems reasonable.

The document n.661 is a contract on the sale of a camel paid in maṣa, which likely refers to Chinese copper coins as suggested by Wang, and is followed by a list of legal stipulations.Footnote 88 This was a commonplace exchange in the region, given that camels were often traded in the Krorainan material. What makes the document noteworthy, however, is the name and epithet of the buyer, the suliḡa Vaḡiti Vadhaḡa. The epithet identifies him as a Sogdian and the name has been reconstructed as the Sogdian name βγyšty-βntk (Vagisti Vandak, ‘Slave of the gods’).Footnote 89 One of the witnesses too carried a Sogdian name, Nani Vadhaḡa, which transcribed the Sogdian name nny-βntk (Nanai-vandak, ‘Slave of Nanaia’).Footnote 90 What these two Sogdians were doing in Khotan, beyond buying a camel, cannot be known, but it does show that Sogdians did travel to, and reside in, Khotan in this period. Presumably, however, Vaḡiti Vadhaḡa also travelled onwards to or past Saca (Endere) where the contract ended up. This seems likely because a number of documents written by Sogdians and using the Sogdian language has also been found in both Niya (Caḍota) and the Lop sites (Kroraina), as well as further east near Dunhuang. At Caḍota was found one fragment of paper by the Sino-Japanese expedition that contained a few lines giving some personal names in Sogdian as well as mentioning both Kucha and the Supi, a polity and a people also known from the Krorainan documents. Interestingly, the paper fragment was originally found crumbled up as a small package and had contained some organic powder thought to have been either a spice or medicine.Footnote 91 Stein meanwhile uncovered a total of six Sogdian fragments from various Lop (Kroraina) sites, one of which was a large and fairly intact letter written on paper, though as of yet none of them have been translated and published in full.Footnote 92 Given their mostly undeciphered and, in many cases, fragmented state little can be said of the activities of Sogdians in Kroraina, but these many fragments do indicate that they travelled and possibly also lived in the region. This is also shown by the so-called Sogdian Ancient LettersFootnote 93 discovered near Dunhuang and dated to around 311 CE.Footnote 94 These documents describe a community of Sogdians living in Dunhuang and further east in various towns in Gansu. Many of them were merchants, and judging by the unfortunately fragmented letter six some were also trading in Kroraina (Kr’wr’n), as the letter writer says he was ordered to go to Kroraina and buy silk there.Footnote 95 As revealed by some of the other letters, the Sogdian merchants dealt in a variety of goods, including pepper, as noted in letter five addressed to ‘the chief merchant Aspandhāt’.Footnote 96 It is, therefore, a distinct possibility that it was a Sogdian merchant that had carried the pepper mentioned in the Kharosthi document n.702 to Kroraina, and possibly other good from the west and south as well.

The kingdom of Kroraina as an actor in long-distance exchange

In summary, the evidence provided by the archaeological and written sources from the kingdom of Kroraina shows that not only were imported goods brought into the oases from distant places, but also that at least some of these were brought by merchants. Furthermore, the sources have shown how Kroraina was part of a vast network of connections, stretching from Sogdiana in western Asia to Gansu in western China. But how were these connections and these journeys made possible? Despite the many books and articles discussing the Silk Road, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the fundamental problem of how travel and trade along these routes might actually have been conducted. This is astonishing given that the regions supposedly traversed by the Silk Road are amongst the most difficult and hazardous in Eurasia, including some of the tallest mountain ranges on earth as well as difficult desert crossings through the Gobi and the Taklamakan. Language and cultural boundaries too had to be negotiated, as seen for example in the case of the Sogdians travelling through Khotan, Kroraina, and Dunhuang.Footnote 97

There is much evidence to suggest that the polities of the Tarim Basin played an important role in solving these problems. Douglas Hitch has pointed to the striking similarities in the rules and language governing contracts throughout the Tarim Basin region from the Krorainan documents (third to fourth century) to the Khotanese documents (seventh to eighth century), similarities also shared with Bactrian legal documents.Footnote 98 He suggests a Kushan precedent for these legal traditions, which seems a plausible explanation. But the fact that these traditions appear to have survived well into the eighth century also shows that they served the local polities well and, while likely not their primary purpose, these common traditions must certainly have eased and facilitated trade through the region. An active attempt to bridge some of these difficulties by a Tarim polity can be seen in the Sino-Kharoshti coins issued in first-century CE Khotan.Footnote 99 These remarkable coins had been struck to the reduced-Attic tetradrachm and drachm that was in use in Bactria at that time and identified the king on the obverse, but gave their weight in Chinese on the reverse.Footnote 100 Admittedly only issued for a short period, and seemingly not particularly widespread beyond Khotan, these coins still clearly represent an attempt at bridging the gap between the Bactrian and the Chinese monetary traditions. Some of these issues, such as the use of the local legal tradition by foreign travellers, could be discussed in the context of the Krorainan sources. But in the next section, I will turn to a different issue, the most fundamental of all ‘Silk Road problems’: travel.

Securing the roads and the Arivag̱a system

Simply crossing between two oases in the Tarim Basin would have posed a serious challenge for any traveller, as indeed the testimonies in many later travelogues bear witness. For example, the route from Dunhuang to Kroraina (Shanshan), as described by the Chinese monk Faxian in the fourth century CE, went through a lifeless wasteland, filled with evil demons and hot winds. A traveller would find no route through it, the only landmarks being the bleached bones of those who had perished along the road.Footnote 101 This is, of course, an exaggeration given for dramatic effect. But it paints a vivid picture of the hardships faced by those traversing these routes and highlights the dangers of losing one’s way. If one adds to this the difficulties of acquiring supplies and the dangers of banditry, the challenge appears all but impossible. Yet, as shown by several Chinese accounts, such journeys were made possible with the aid of local polities and people. In the case of Faxian, his group was first given supplies by the prefect of Dunhuang, before they sought aid from the local rulers and Buddhist communities situated in kingdoms through the Tarim Basin.Footnote 102 The Hanshu, which includes an account of the route to Northern India in the first century BCE, similarly states that ‘[f]or asses, stock animals and transported provisions, they (the envoys) depend on supplies from the various states to maintain themselves.’ If the local states were unable or unwilling to provide supplies however, the envoys would starve to death in the wastes.Footnote 103 In other words, the local polities played an essential role in facilitating travel according to the Chinese accounts.

Turning to the material from Kroraina, there are a number of documents dealing with such issues. As revealed by documents such as n.423, n.548, and n.555,Footnote 104 the roads were at times not considered secure and as described in document n.165 there was at times the danger of tax transports being plundered en-route.Footnote 105 To remedy this situation the Krorainan court had several measures in place. For the transportation of the tax to the capital a class of officers called the toṃgha were charged with security (see documents n.357, 387, and 622), each officer given a unit of twenty men to aid him in this (see document n.96). Several royal commands also refer to the maintenance and occupation of the pirova, a word meaning fort or small fortification.Footnote 106 Small forts of a type seemingly matching the pirova have also been found archaeologically throughout Kroraina, including the older fort in the southern part of the Endere (Saca) site and the row of forts uncovered along what must have been the former shore of Lake Lop Nur near Kroraina itself.Footnote 107 The pirova mentioned in the surviving Kharosthi documents appears to have been on the road near Caḍota (Niya), and had its own water supply as shown by document n.120, though a pirova is also mentioned in one document from Saca (Endere) (see document n.665).Footnote 108 From the pirova the road in and out of Caḍota could be controlled, and if necessary blocked, as shown by documents n.310 and n.639.Footnote 109 But in addition to controlling the road the pirova also appears to have been used by, and offered shelter to, travellers, as suggested by both document n.333 and n.639.Footnote 110

In addition to these efforts to secure the roads, the Krorainan sources mention many journeys through the kingdom by royal envoys on missions to Khotan. As seen in document n.14, quoted in the first section, a system was in place to provide these envoys with the necessities for the journey, with local officials in each major oases expected to provide guards, animals or supplies as needed (see documents n.14, 22, 86, 135, 214, 223, 248, 251, 253, 330, 362, 367, 388, 637, and 686). It is difficult to determine the extent to which this system would have extended to other travellers, though judging from document n.686 (deriving from the Lop (Kroraina) site) Khotanese envoys and various groups of Chinese were supplied with provisions.Footnote 111

In addition to supplies and animals however a number of documents also specify that the royal envoys travelling to Khotan were to be provided with a suitable man as Arivag̱a (see documents n.10, 22, 135, 244, 251, 253, 388, 438, 507, 557, 569, and 593).Footnote 112 This word can, from the context, be interpreted as meaning ‘guide’ as seen in document n.135 where the arivag̱a is to ‘go in front of’ the envoys on the way to Khotan.Footnote 113 Harry Falk has, however, proposed that the etymological root of the word can be traced to Sanskrit arivargin meaning ‘mediator’ or ‘protector’, roles which the Krorainan arivag̱a might also have fulfilled.Footnote 114 Not anybody could be appointed arivag̱a, for a man who was to be arivag̱a had to know the Khotanese mata, that is the routes to Khotan and possibly also the customs of the area. This knowledge was passed down over the generations, from father to son, and as such being an arivag̱a was also a hereditary duty as shown by documents n.10 and n.438. Clearly an active system at the time of the Krorainan documents, there are also strong indications that the arivag̱a institution was far older, as its hereditary nature is said to go back literally to the ‘father’s fathers’ (see documents n.10 and n.438). No payment or reimbursement is ever mentioned for the arivag̱a, though they were exempt from other state duties. Furthermore, the men who served as arivag̱a do appear to have been men of some standing. This can be discerned from the fact that they had to bring their own animals for their missions, as well as being shown by their inclusions as witnesses in lists of azade, that is noble or freeborn men.Footnote 115

We do not know if the arivag̱a system was applied to other routes than those leading from Caḍota to Khotan, though this seems highly likely. Arivag̱a as a title is, however, found in at least one other source, namely in a votive copper-plate inscription from the Gandharan region dating to the first century CE. Found in a Buddhist stupa at Rani Dab in modern-day Pakistan, the lengthy inscription had been left by a man named Helagupta, son of Demetrios, both of them carrying the title arivagi.Footnote 116 Nothing more is said of Helagupta’s profession and as such one should be careful in equating this arivagi with the Krorainan arivag̱a even if the word is clearly the same. It would, however, seem worthwhile to examine the many rock inscriptions from the upper Indus valleys for this title, though, as of yet, I have not been able to find other instances of this word. This distant reappearance of the title is at any rate interesting, whatever its meaning in the Gandhari context, providing as it does yet another link between Kroraina and the Indian subcontinent.

More important for our purposes is that in the Caḍotan arivag̱a system we find an actual solution to the problems of traversing the routes between oases in the Tarim Basin. They show that there existed at Caḍota an institution of hereditary guides, regulated by local law and appointed by local officials, who could be called upon when journeys had to be undertaken across the deserts to Khotan. Like pilots along dangerous coastlines, men such as these must surely have been crucial in facilitating the movement of people, whether envoys, monks, or merchants, across the ‘sea’ of the Taklamakan.

A Silk Road exchange network

Bringing the three parts of this article’s analysis together, we have seen how the Krorainan elites consumed large quantities of imported goods, drawing on materials, crafted items, and designs from distant regions, including the Chinese plains in the east, the Iranian world in the west, and the Indian Ocean to the south. They were thus tapping into a larger network of exchange, which shaped local tastes and patterns of consumption. Yet at the same time, these goods were not the accidental droppings of some imperial caravan. Rather, as made evident by both the quantity of certain imports (like silk), as well as the regularity with which certain products arrived (like spices), these imported goods found in the kingdom of Kroraina were actively sought for local purposes. Thus, while the wider system was shaping the local, the local’s demand for luxurious imports would have been an important factor in fuelling the exchange system itself. As demonstrated in the latter part of this article, many of the imports were brought to Kroraina through mercantile connections. In these connections too we see a diversity of actors, including those with probably connections to neighbouring kingdoms such as Khotan, as well as Chinese and Sogdian merchants. The presence of these merchants further testifies to the truly vast scale of Kroraina’s networks of exchange, reaching across most of Eurasia from China in the east to Sogdiana in the west.

Despite the focus here on foreign goods and foreign merchants, I have endeavoured to show in this article that it would be wrong to consider the kingdoms of the southern Tarim Basin as passive recipients in a large global system beyond their agency. Instead, the evidence demonstrates clearly that the kingdoms of the southern Tarim Basin played a crucial role in facilitating the Silk Road network as a whole, by acting as hubs and by providing solutions to the fundamental problems of long-distance exchange. This was shown by the efforts of the kingdom to maintain security and infrastructure through the areas under its control. Even more important, however, were local institutions, likely dating back to periods preceding our documentary records. Notably, the arivag̱a system which would have been crucial in making travel across the Tarim Basin possible (just as local guides did for many twentieth-century explorers).

Our Krorainan case underlines the importance of the local to the global, for though likely not intentional the systems of local infrastructure created and maintained by the Krorainan polity must have played a crucial role in allowing movement and contact through the southern Tarim Basin in antiquity. Taken together the Kharosthi, Chinese, and Sogdian documents, as well as the archaeological material, from the kingdom of Kroraina permit us to look beyond the singular reference to a merchant in Kharosthi document n.35, and allows us to reconsider the place of the kingdom of Kroraina within Silk Road history. As noted by Matsuda, the oases of the region were far from isolated islands and, as we have seen, the Krorainan oases were deeply involved with trade, acting not merely as middlemen, but playing a crucial role in creating and maintaining the Silk Road networks for their own purposes, much like Matsuda suggested. It should also be stressed that this article has looked merely upon the strictly material and economic connections of Kroraina, and other studies, for example, of its Buddhist culture would certainly reveal connections to the wider Buddhist world, a world discussed in Signe Cohen’s article in this SI.

Returning to the wider perspective, the conclusions drawn from this case study should encourage us to re-examine parts of the traditional Silk Road narrative, challenging both the commonly held notion of the third and fourth centuries as periods of little activity, and the still predominant notion of the primacy of great empires. In this respect, the usefulness of global history as a theoretical framework can be seen, with its focus on both local relationship and responses to the global. Additionally, it encourages us to explore the totality of a system, rather than any single primary actor. I would, therefore, argue that a global historical approach to the Silk Road exchange networks is in order, and I believe such an approach would demand a more thorough examination of the evidence from Inner Asia. Certainly, Kroraina and similar oases-polities, rather than being seen as isolated islands, ought to be included in any serious discussions of trans-Eurasian trade in late antiquity as they played a crucial role in facilitating and maintaining the ‘Silk Road’ trade network. Returning to Matsuda’s island metaphor, one could say that the Krorainan oases of the second to fourth century CE were metaphorical safe harbours in a sea of sand, and just like harbours they were crucial hubs binding together wide-reaching networks of exchange and interaction.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Matthew Cobb for hosting the conference Re-Thinking Globalisation in the Ancient World in which the idea for this special issue was sparked, and for his hard work in making this special issue possible. I would also like to thank Minoru Inaba for his help accessing the Japanese scholarship on Inner Asia and Nicholas Sims-Williams for his help with the Sogdian material and for sharing his forthcoming translations with me.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Tomas Larsen Høisæter is an associate professor at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences. He finished his Ph.D. project, ‘At the Crossroad of the Ancient World: The role of the kingdom of Kroraina on the Silk Roads between the third and fifth centuries CE’ in 2020, which examines the kingdom of Kroraina in late antiquity and its connections with the Silk Road exchange network.