In 1825, Baiǰu 拜住 (1298–1323) of Jalayir, a prominent minister of Yeke Mongγol Ulus, was posthumously made Duke of Loyal Benefaction (Zhongxian gong 忠獻公) and enshrined in the Shrine of Loyal Martyrs (Zhongyi ci 忠義祠) in Dali 大荔 County, Shaanxi, by the imperial edict of the Daoguang 道光 emperor (r.1820–50). The edict was issued in accordance with a petition from Ošan 鄂山 (1770–1838), a Mongol bannerman affiliated with the Plain Blue Banner (Zhenglanqi 正藍旗) serving at the time as the Grand Coordinator of Shaanxi (Shaanxi xunfu 陝西巡撫). The very succinct account of this enshrinement (consisting of only twenty-seven characters) in the Veritable Records Footnote 1 may seem quite abrupt and out of place, begging the following questions: Why was the long-dead Yuan minister honored five centuries after his death? Was this a personal endeavor to commemorate the loyal subject of his alleged ancestors by Ošan, a Borjigid Mongol bannerman? The Veritable Records does not provide any further clues; however, as discussed below, the enshrinement has exerted a profound impact on local history.Footnote 2

This study sheds light on the largely unknown trajectories of the emergence of Yuan non-Han ancestry in the late Qing North China.Footnote 3 During the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, under the rule of Yeke Mongγol Ulus, or the Mongol Empire, a large number of migrants from Central Eurasia poured into North China. After the historical episode known as “The Uprising of the Five Barbarians” (Wuhu luanhua 五胡亂華) in the fourth to sixth centuries, the Jurchen and Mongol invasions in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries ushered in a second phase of full-fledged non-Chinese conquests in the history of China. Today, most descendants of the Yuan non-Han migrants appear to have been linguistically and customarily assimilated into the “Han” majority. However, as recent scholarship has shown, non-Han people were not unilaterally absorbed into the Han or forced to abandon their ancestral memories. After 1368, numerous non-Han people served in the Ming court and army, exerting significant influence over the Ming military, administrative systems, and court culture.Footnote 4 Centuries after the demise of Mongol rule, the descendants of Yuan non-Han immigrants could commemorate their ancestry.Footnote 5

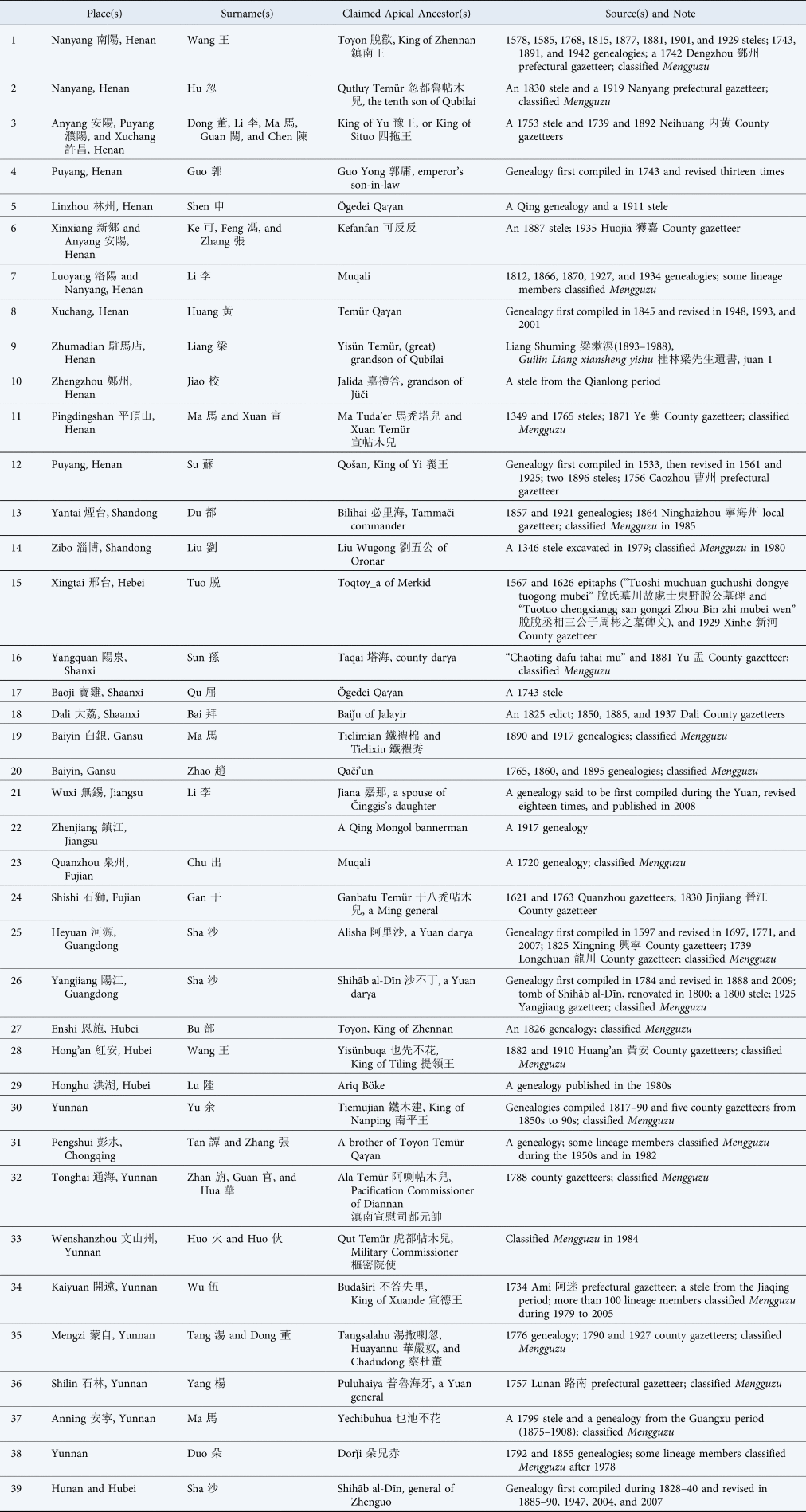

The recent three decades saw the publication of not a few comprehensive reports of the non-Han ethnic groups in Han-majority provinces. These groups include those who were classified as Hanzu during the Ethnic Classification Project (民族识别工作) but today claim Mengguzu ancestry. Scholars in mainland China contributed to most of these reports, among which the most comprehensive is Mengguzu and Their Descendants Residing Scattered in the Hinterland of Our Mother Country (Sanju zai zuguoneidi de mengguzu ji houyi 散居在祖国内地的蒙古族及后裔).Footnote 6 This book, a product of the author's two-decades of painstaking fieldwork, enumerates thirty-nine such cases in Henan, Hebei, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Shandong, Jiangsu, Fujian, Guangdong, Hubei, Chongqing, and Yunnan (Table 1).

Table 1. Non-Han Ancestry Resurgences in Sanju zai zuguoneidi de mengguzu ji houyi

A quick survey of Table 1 reveals that the earliest written ancestral evidence in many cases emerged in the form of steles and genealogical texts during the late eighteenth to late nineteenth centuries and was later included in local gazetteers. Why did the commemorations take place during the late Qing, as in Baiǰu's case?

The emergence of Yuan non-Han ancestries gives us a glimpse of the bottom-up perspectives concerning identity making in Qing China. The conventional view is that Manchu rulers upheld Confucian ideals in China proper and presented themselves as legitimate Chinese emperors, while the Eight Banner system played a crucial role in constructing and maintaining Qing imperial governance. Institutionally, as Mark Elliott contends, “the Manchu's banner system stood for all that was not Chinese about them” and drew a clear demarcation between Manchus and the Han in the Qing administrative, military, and bureaucratic systems.Footnote 7 How should we contextualize the emergent non-Han ancestries in this overall ethnic landscape of Qing China?

Focusing on the case of Baiǰu's enshrinement, this paper offers two conclusions. First, the commemoration of non-Han ancestries seems to have been aroused by the two-century-long imperial project of compiling the Gazetteers of the Great Qing Empire, over the course of which the state reiterated extensive surveys of local worthies, chaste women, and martyred loyal subjects, including those from previous dynasties. Importantly, the surveys coincided with the rise of epigraphic studies that featured exhaustive epigraphic fieldwork, which gave rise to the reinterpretation and replication of the Yuan epigraphy, rendering Yuan steles one of the most adamant proofs of ancestral claims. Second, apart from the intention of the Qing court, gazetteer compilation projects functioned as a type of classification project, if not necessarily ethnicity. The ancestries classified by the Qing came to coexist with modern minzu identities classified by the Ethnic Classification Project during the mid-twentieth century.

The Bai Lineage of Dali County, Eastern Shaanxi

The southernmost parts of Dali County used to be the floodplain of the Wei River 渭河 and the Luo River 洛河, the flooding of which created numerous soaring dunes in the area over the centuries. Though most dunes have been leveled off today, we can still see the remnant of the capricious landscape at the “Sandy Land Garden” (Shayuan 沙苑), a major tourist destination in the county, encompassing 600 square kilometers of land. Baijia Village is located approximately one and half kilometers north of the northern shore of the Wei River in the middle of the floodplain.

Predictably, sterile soil and frequent floods were seen as key features of this region over the centuries. Li Yuanchun 李元春 (1769–1854), one of the most eminent figures in the Learning of Guanzhong (Guanxue 關學) tradition during the QingFootnote 8 and a native of the neighboring Chaoyi county, states in a letter to a friend:

In recent years, famines have made people starve, and banditry is prevalent everywhere. Yet, [the banditry of] Guanzhong is the most flagrant. In Guanzhong, [the banditry in] Tongzhou and Chaoyi is the most flagrant. In the region between the Luo and Wei Rivers, [the banditry in] Shayuan is the most flagrant. Between the two rivers, bandits comprised of both Han and Hui Muslims have long set up hideouts in settlements like Yangcun, Sucun, Dacun, Baijia, and Dingjia Yuanzi, regardless of whether the famine hits the region. Dozens of them used to band up together after sunset every fall and spring, wielding ladders and weapons. They openly obstructed traffic and returned to the villages after midnight.Footnote 9 (italics mine)

During the early nineteenth century, Baijia Village appeared to have been situated in the middle of the vast floodplain that was a hotbed of brigandage in the eyes of Li.

During my second visitFootnote 10 to Baijia Village on August 17 and 18, 2019, I had the opportunity to participate in two group discussions (zuotanhui 座談會), held first in Baijiacun Village, and then in Tiejia Village 帖家村, located approximately 500 meters to the north of Baijia Village. According to the village leaders and elderly villagers, there are three “Mongol” surnames in Dali: Bai 拜, Tie 帖/铁, and Da 达/答. They collectively used to be called “Dazi” 鞑子 by their neighbors, with an old saying: “Do not boggle at Tie, Da, and Bai surnames. They are not Huihui, but aotai” (帖、答、拜,不用猜。不是回回,是敖台。). In both group discussions at the Baijiacun and Tiejiacun villages, no one knew exactly what aotai meant.

Baijiacun villagers told us their ancestral history, chronologically reorganized as follows: The Bai are direct descendants of Baiǰu. The resident ancestor, Dulin 篤麟, a son of Baiǰu, migrated from Hebei to Pingjiang 平江, Zhejiang, and then to Dali County in the early Ming and named his new home village “Wuliucun” 五柳村, with only a few households comprised of his kin. As the population grew, the village was renamed “Xingpingcun 興平村.” In the oral history of the villagers, the great majority of the village population has been comprised of the Bai lineage members who uphold Confucian values. The Tongzhi Hui Revolt (1862–77) devastated Dali, with numerous villagers fleeing or being killed by their former Hui Muslim neighbors. Although there were two Muslim magnate lineages in Dali, Qiao 喬 and Dian 甸, after General Zuo Zongtang 左宗棠 (1812–85) drove out the Muslim rebels from Shaanxi during the Hui Muslim War (1862–77), only a few Muslims remained in Dali. In Baijia Village, only one Qiao-surnamed household remained, having abandoned its faith. Muslims in Dali today are mostly descendants of immigrants from Zhejiang, Fujian, Jiangsu, and Jiangxi provinces, sent by the Qing government after the Tongzhi Hui Revolt. In 1937 and 1942, fleeing floods, famine, and the Japanese invasion, waves of Muslim refugees from Henan settled in Dali. Today, even among the members of the Bai lineage, there are some Muslims. Baijia Village was originally located much closer to the Wei River and was surrounded by thick clay walls. Before the construction of the Sanmenxia 三門峽 Dam, in the 1956, the more than one-third of the villagers were evacuated to Ximin Town 西民郷 in Zhongning 中寧 County in Ningxia. The walled village was abandoned and eventually leveled, along with four ancestral halls owned by two branch households.

The ancestral graveyard was located several hundred meters south of the former village. Unattended, it was buried in sand during a flood in the 1950s. An 1832 stele commemorating the 1825 imperial edict was also buried, but its replica, put up in 1925, still exists (discussed below). By 1962, villagers returned from Ningxia and established a new village north of their original site. In 1977, a feud (xiedou 械鬥) erupted with the neighboring village over wheat fields. As a result, a new boundary between the two villages was drawn, leaving the former graveyard site now within the territory of the neighboring village (this is one of the reasons the Bai lineage has not yet excavated the site to retrieve the ancestral relics).

Similarly, in Tiejia Village, the Tie lineage members told me that they are direct descendants of Baiǰu. Some also said that their apical ancestor was a wet nurse of a son of Činggis Qan while some others claimed that their ancestor was Temüǰin himself. The Tie lineage members used to marry only from the Bai and Da lineages. Before 1955, their ancestors were divided into three households, each comprising nine families, with some Tie lineage relatives residing in Pucheng 浦城 County. The lineage had a genealogy recorded on silk with a painting of Činggis Qan. Unfortunately, the genealogy was lost during the “Destroying the Four Olds” (Po sijiu 破四旧) movement. Evidently, ancestral memory/narratives among Tie lineage members are much more obscure and inconsistent compared to those of the Bai lineage.

As seen above, it is remarkable that the crucial moment in the history of the Bai lineage was the enshrinement of Baiǰu in 1825. Why did Emperor Daoguang issue an edict to this particular lineage to enshrine Baiǰu? Fortunately, a petition to enshrine Baiǰu is recorded in the Sequel to the Existent Manuscripts of the Old Dali County Gazetteer (續修大荔縣舊志存稿) published in 1937. The essay “Record of the Enshrinement of Lord Bai Zhongxian, Comprised of Original Petition and Memorial” (拜忠獻公奉旨入祀記 集原呈及題奏)Footnote 11 was authored by Li Yuanchun, a powerful advocate of local history. It succinctly narrates the genealogy of Baiǰu for seven generations, from Gü’ün U'a (孔溫窟哇) of Jalayir, his son, Muqali, then down to Baiǰu, drawing on Yuanshi. Subsequently, the petition relentlessly praises the righteousness, undying loyalty, and self-sacrifice of Baiǰu, lamenting his assassination together with that of Šidebala (Gegen Qaγan, r.1320–23) at Nanpo 南坡 in the coup d’état orchestrated by Tegši (d.1323). What is worth underlining is that the petition goes on listing the names of the petitioners: Liu Xueshi 劉學師, Instructor of County School (縣教諭); Wang Lian 王璉, scholarship student of the county school (廩增附生); Lord Deng 鄧, County Magistrate; Lord Xu 徐, Prefect; Lord E 鄂, Circuit Intendant; Lord Deng 鄧, Provincial Governor; and Lord E 鄂 (i.e. Ošan), Grand Coordinator. This list suggests that the person who initiated the enshrinement was not likely Ošan, who would soon have to confront the revolt of Jāhangīr Khwāja (1788–1828) in Xinjiang, nor was it his subordinate local officials, but the instructor and students of the Dali county school.

In “Bai zhongxian chongsi ji” (拜忠獻崇祀記), an essay wrapping up the process of the enshrinement (recorded in Li Yuanchun's literary collection), Li states that it was Bai Wenwei 拜文偉 (dates unknown), the descendant of Baiǰu, who submitted the petition in the first place, presumably to the county government or school. Li also claims that Wenwei owned a family genealogy (jiapu 家譜) and a genealogical chart painted on a silk sheet (shenzhou 神軸) and thus “[their] genealogy is demonstrably able to be explored in detail” (世系確然可詳).Footnote 12 These fragmentary accounts suggest that the enshrinement of Baiǰu was a part of the project of Li Yuanchun and his colleagues to promote local history, arguably foreseeing the future recompilation of the Gazetteer of the Empire.

The 1937 Dali County Gazetteer reflects on the devastation of the revolt, recounting that the Shayuan floodplain had become completely desolate.Footnote 13 According to the oral history prevalent in the village, only eight households (bahu 八戸) remained in Baijiacun after the Tongzhi Hui Revolt. Nevertheless, the enshrinement and consequent official recognition of Mongol ancestry greatly bolstered the status of the Bai lineage in the county, as the local government kept on commemorating Baiǰu. The Shrine of Loyal Martyrs in the county seat was rebuilt in 1869 by local gentry,Footnote 14 and the tomb of Baiǰu, as well as the 1832 stele, was finally recorded in the 1879 Tongzhou Prefectural Gazetteer.Footnote 15 A stele recently excavated at the site of the previous Baijia village, titled “Chijing Yuan youxiang dongpingwang Bai zhongxiangong hui zhu shendaobei” (敕旌元右相東平王拜忠獻公諱住神道碑) (dated 1925), is a replica of the eroded 1832 stele built to commemorate the enshrinement of Baiǰu, allegedly in the ancestral graveyard now buried underground. This 1925 stele lists the eminent members of the Bai lineage at the time, including those called “manager of the three households” (sanhu jingli 三戶經理) and “manager of the six households” (liumenhu jingliren 六門戶經理人) and states that the lineage comprised three branches: beishe 北社, xishe 西社, and nanshe 南社. This stele inscription demonstrates that in the early twentieth century, the Bai lineage appears to have been a well-organized kinship organization united under the Yuan non-Han ancestry.

As the Bai lineage prospered, their ancestral narrative came to be recorded in local gazetteers. In introducing the Shrine of the Loyal Martyrdom and Filial Piety (Zhongyi xiaodi ci 忠義孝悌祠, i.e., former Zhongyi ci 忠義祠), the 1937 gazetteer remarks that though Baiǰu's name was not found on the 1729 stele of the shrine (for he had not been enshrined then), there was a great plaque displaying his name, official title, and posthumous honorary title in its main hall. Members of the Bai lineage made seasonal pilgrimages to the shrine to burn incense, almost exclusively occupying the shrine as the ancestral hall of their lineage. The gazetteer authors complained, “Yet, the shrine is originally a public domain and those enshrined are all worthies in the previous dynasties. Now a family denies this for private reasons. How can efficacious lord Zhongxian (i.e. Baiǰu) stay calm in this abnormality?” (然祠本公地,祀皆前賢。 今以一家之私,而抹倒之。忠獻有靈,豈忍安乎).Footnote 16 Taking over an official shrine as the lineage ancestral hall demonstrates the lineage's authority as descendants of a righteous historical figure, to say the least.

It is important to note that the Bai lineage and its members were not called Mongols (Menggu) in any sources before 1937. Instead, the Bai lineage was commonly described as the descendants of Baiǰu, and his “ethnicity” did not seem to attract any attention from the lineage members and their neighbors.

Regarding the Bai lineage members as Mongols was a twentieth-century perception, starting from the 1937 Dali County Gazetteer, which states that

There are Mongols (Mengzu 蒙族) south of the desert, with three surnames, Tie, Da, and Bai. In the previous Ming, [their ancestors] migrated from Yan 燕 [i.e., northern Hebei] to this county. They are robust and endure heavy labor. Having come into contact with and gradually acculturated with Han people (Hanzu 漢族), [the Mongols] have intermarried with Han people for a long time.

沙南又有蒙族三姓,曰鐵,曰答,曰拜,自前明由燕遷居本縣。其人壯實耐勞,與漢族漸習聯絡,久通婚姻。).Footnote 17

Nie Yurun 聶雨潤 (dates unknown), the chief compiler of the 1937 gazetteer and the incumbent county magistrate, graduated from Pekin Academy (Beijing huiwen zhongxue 北京匯文中學) and had most likely learned the modern notion of race (minzu/zhongzu), the discourse of which became widespread by the use of stereotypic description of the Mongols (being robust and enduring heavy labor).Footnote 18 The conversion from the descendants of the loyal subject to “robust Mongols” in the 1937 county gazetteer sheds light on the process in which premodern ancestry was distilled into modern ethnicity.

During the Ethnic Classification Project, the entire Bai lineage was classified Hanzu for reasons unknown to the lineage members today. Yet, the lineage members do not miss an opportunity to assert their “original” Mengguzu identity. Since 2014, some Bai lineage members, who are also village leaders, have attended the annual worship rituals of Muqali (d. 1223), the great-great-great-great grandfather of Baiǰu, held in Luoyang and Üüšin qošiɣu (Wushenqi 烏審旗), on the third day of the third lunar month and thirteenth and fourteenth days in the fifth lunar month, respectively, to consolidate the kinship tie with other self-claimed descendants of Muqali. Recently, Bai lineage members have claimed that they are one of the prominent nodal points in the revival of the Mengguzu identity in China and beyond, as far as Kazakhstan, by publishing their ancestral claims online.Footnote 19

The Bai Lineage as Descendants of a Righteous Subject

Although we have few sources tracing the history of the Bai lineage before 1825, the petition authored by Li Yuanchun contains an interesting sentence asserting that the state encouraged local governments and people in its jurisdiction to report righteous achievements. At the outset of the petition, Li also remarks,

I humbly suppose loyal subjects dedicate their life to the state, and if their effulgent achievements become widely known, a virtuous emperor would praise their wisdom and reveal the righteousness to the world, without leaving out [even the cases from] the previous dynasties. Delving into the virtuous deeds in ancient records, we reverently admire the perpetual fame [of meritorious subjects]. Considering the esteemed norms in the homeland, the spread of benevolence and compassion is our hope.Footnote 20

In other words, Li Yuanchun candidly stressed the necessity to officially honor loyal subjects under any Chinese state in history in order to uphold and enhance morality.

Why did Li Yuanchun believe that the Qing state needed to honor loyal subjects from previous dynasties? In “Bai zhongxian chongsi ji,” having succinctly summarized the illustrious ancestry and benevolent achievements of Baiǰu, Li rationalizes his argument:

The principle of imperial commendation concerns worthiness and does not concern someone's status to inspire the people under Heaven and sustain the code of morals for the ages. Let alone the Qilin Pavilion of the Han, the Lingyan Pavilion of the Tang, and the Zhaoxun and Chongde Pavilions of the Song [where the portraits of the meritorious subjects were displayed] have been official schools and shrines of loyal martyrdom and filial piety, in which even an ordinary man with slight moral integrity can be enshrined, to say nothing of those who benefitted the state and its people. Our state honors good and honest people, and there have been ample such precedents. Recently, six scholars from previous dynasties, including Lord Lu Zhi 陸䞇 (754–805), were enshrined in the Temple of Confucius. Many more were also enshrined in the shrines of local worthies in prefectures and counties.Footnote 21

The original Classical Chinese term for “the principle of imperial commendation,” baochong zhi dian (褒崇之典), is a common usage that stands for honoring meritorious subjects. However, Li Yuanchun arguably uses this term with particular imperial edicts issued during the reign of the Qianlong emperor in his mind. On the eighth day of the second month in the forty-first year of the Qianlong period (1776), the Grand Secretariat and nine other ministers reported to the emperor, petitioning to posthumously honor the Ming loyal subjects who died for the dynasty. The petitioners submitted the list of candidates selected from Mingshi and Collated Successive Comprehensive Mirrors in Aid of Governance Edited by Imperial Instruction (Yupi lidai tongjian jilan 御批歷代通鑑輯覽, compiled in 1768). The Qianlong emperor approved of the petition and titled the list Record of Martyred Subjects in the Previous Dynasty (Shengchao xunjie zhuchen lu 勝朝殉節諸臣錄). Then the emperor issued a decree to have the record printed and published from the Wuying Palace (Wuying dian 武英殿) as well as to enshrine the Ming loyal subjects at the Shrines of Loyal Martyrs in the localities. Having pointed out that more than 3,600 martyred loyal subjects were selected from Mingshi, Collated Successive Comprehensive Mirrors in Aid of Governance Edited by Imperial Instruction, Provincial Gazetteers, and Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire, the emperor went on to declare that no further survey and commemoration would be conducted.Footnote 22

This decree of the Qianlong emperor pinpoints the potential problems that the emperor and his government would most likely confront if they expanded the commemoration project endlessly. As numerous people died resisting the advancing Qing army or sacrificed their lives for the states even before the Ming, the cost of commemoration would be astronomical if the central government allowed further petitions to enshrine one's ancestor. An enshrinement could be accompanied by privileges to the martyr's descendants. In the case of the Bai lineage, upon the enshrinement of Baiǰu, six persons, presumably members of the Bai lineage, were granted the post of “keepers of shrine (fengsisheng 奉祀生),” the hereditary position assigned to maintain sacrifices to a particular enshrined person.Footnote 23 Apparently, generous granting of the status of loyal martyr could eventually be a weighty burden on the local financial and administrative system. It was in the same vein that the Qianlong emperor's reluctance to expand the scope of the survey was shared by his ministers. The memorial submitted in 1775 by Šühede 舒赫德 (1710–77) and Yu Minzhong 于敏中 (1714–80)—also included in the beginning of Record of Martyred Subjects in the Previous Dynasty—had expressed more practical concerns, such as the difficulty of verifying the pieces of historical evidence submitted by the self-claimed descendants of the martyrs who were not recorded in Mingshi or other official historiographies.Footnote 24

Since the Kangxi 康熙 period (1662–1722), the Qing state had sporadically commended loyal Ming subjects, whereas their number did not exceed several dozen at a time. The commendation of loyal Ming subjects was unprecedented in number not only in the Qing but throughout Chinese history. As stated in the 1776 decree, the Qianlong emperor and his ministers intended to bestow this royal blessing for the last time. They anticipated the consequences otherwise: local governments filled with petitioners, shrines crammed with martyrs, and villages crowded with martyrs’ descendants claiming honor and privileges. However, contrary to their expectations, the publication of the Record of Martyred Subjects seems only to have instigated further petitions as the Qing state encouraged its subjects to report righteous persons simultaneously.Footnote 25

With the 1775 memorial and the 1776 decree, both included with the Record of Martyred Subjects in the Previous Dynasty in mind, we find that Li Yuanchun quite skillfully dispels the concerns in the memorial and decree—reckless enshrinements of the loyal subjects—in the petition to enshrine Baiǰu. Having pointed out that “the virtuous emperor praises the wisdom and reveals the righteousness to the world, without leaving out [even the cases in] the previous dynasties,” as seen above, he cites Yuanshi to underline Baiǰu's loyalty attested in official history. He devoted about half the petition to describe Baiǰu's loyal service and martyrdom at the coup d’état at Nanpo, with rhetorical questions like “His descendants have resided on the soil of Dali without a proper sacrifice being conducted. What does his spirit rely on [to exist]? [He] ought to be reverently enshrined to console the loyal spirit” (後嗣遺於荔土,煙祀未舉,靈魂何憑?應請崇祀,以慰忠魂。).Footnote 26 Similar questions are frequently attested in petitions for the enshrinement of commemorative inscriptions for loyal Ming subjects recorded in contemporary local gazetteers. Li Yuanchun was clearly aware of the principle of enshrinement publicized by state-sponsored publications such as Record of Martyred Subjects in the Previous Dynasty.

The case of the Bai lineage suggests that the emergence of Yuan non-Han ancestries during the late Qing period was associated with repeated efforts to compile local gazetteers, which were necessitated by the two-century-long Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire project. Originally, the Qing state intended to gather information to compile a comprehensive gazetteer of its realm. As a secondary project of compiling the gazetteer of the empire, the state permissively commended those who sacrificed their lives for the state. As the case of the Bai lineage shows, from a bottom-up perspective, the gazetteer compilation project aroused aspirations in local societies to honor one's ancestry and subsequently obtain relevant privileges, both tangible and intangible. In the concluding paragraph of “Bai zhongxian chongsi ji,” Li Yuanchun endorses the veracity of the Bai lineage's ancestral claim, pointing out that “the Bai have resided in the depth of the wind-blasted desert. Who would have inquired (i.e., primed them with) the Yuan history?” (拜氏居篆沙之深,誰復與問元代故事?).Footnote 27 Indeed, the fact that the lineage residing in a bandit-infested barren region spontaneously sought state certification of their ancestry corroborates that the Qing commemoration project widely served as a golden opportunity to assert and legitimize one's ancestral narrative in the late Qing society.

During the late eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, as Roger Shih-Chieh Lo has demonstrated, the Qing court desperately sought to sustain its governance over conflicting groups in local society by authorizing and patronizing the local popular religions revered by each party in ever-increasing local conflicts.Footnote 28 State certification of pre-Ming loyal subjects, with their number spiking after the mid-eighteenth century, could be contextualized in the same vein. With mounting social unrest, local administrators faced insurmountable challenges in sustaining and permeating state authority into different social strata. When applicant lineage members and their acquaintances took part in local governance in a broad sense by being clerks, public school students, and prominent gentry elites, and when they reiterated imperial decrees requesting thorough surveys of honorable conduct, it was not likely a favorable option for local administrators to bluntly reject petitions.

As shown above, Li Yuanchun's “Record of enshrinement of lord Bai Zhongxian, with the original petition and memorial” enumerates the officials, from county magistrate up to provincial grand coordinator, with whom Li and his friends “submitted the petition with one heart and reported to the throne all together” (同心申奏,協力具題). This list indicates that such an application could attract the attention of and be smoothly approved by the bureaucratic hierarchy as long as it fulfilled appropriate conditions, such as written evidence of the achievements of the righteous person to be enshrined, testimonies in the locality, and support from the local academic authority. It cannot be a mere coincidence that in most of the cases in Table 1, the apical ancestors were commended for their loyalty to Yuan or their benevolent rule as a local administrator in the locality.Footnote 29

Age of Gazetteer Compilation and Epigraphic Study

Why did Li Yuanchun assist with the Bai lineage's enshrinement project? In the works recorded in his literary collection, Li Yuanchun repeatedly states that he was planning to publish a new local gazetteer of his home county, Chaoyi, because of his dissatisfaction with the previous county gazetteer compiled by Bi Yuan 畢沅 (1730–97).Footnote 30 In compiling the new gazetteer, in its preface, Li declares his steadfast policy to exhaustively survey local righteousness:

The Gazetteer of the Empire (Yitongzhi 一統志) has been compiled since the Ming, and prefecture and county gazetteers have been its primary source. The Gazetteer of the Empire was the primary source of information on dynastic history. Recently during the Daoguang period, the state recompiled the Gazetteer of the Empire and issued an order: “few chaste women and righteous deeds [to be recorded in the gazetteer] have been reported by prefectures and counties. This is because local clerks [in charge of the survey] demand bribes [to enlist cases]. Henceforth, there must not be such a suppression.” In my opinion, there were, in fact, sources hidden in the villages, among which few were known to the public. Only one chaste woman was reported from my village, and it cost a lot [to have it reported. Academic pieces of Wang Fuzhai were collected from my village, but have not been reported. Although we sought to report everything worthy of the State, many remained unreported. This is because it is not easy to fully reveal the facts through exhaustive surveys.Footnote 31

In stark contrast to the concerns of the Qianlong emperor and his ministers addressed in the 1775 memorial and the 1776 decree, in the eyes of Li Yuanchun, the repeated commemorations in local gazetteers had fallen woefully short of commemorating even a glimpse of the admirable local cultural tradition. Li's dissatisfaction could also be derived from the fact that the previous gazetteers were not compiled by the Guanzhong local scholars. Compiling new local gazetteers by himself, he may well have made the enshrinement of Baiǰu a part of the gazetteer compilation project, which aimed to promote the significance of their locality in the gazetteer of the empire.

It is crucially important to understand, as Li states in the beginning of the letter cited above, all the gazetteers at county, prefectural, and provincial levels were compiled to be source materials for the gazetteer of the empire (yitongzhi 一統志). The Yuan, Ming, and Qing empires all compiled the gazetteer of the empire and, as centuries passed, the scale of the compilation project gradually expanded. After the Ming Dynasty, the central court ordered each county and prefecture to compile its own gazetteer to provide basic data for the gazetteer of the empire.Footnote 32 Since the compilation of the Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire (Daqing yitongzhi 大清一統志) was commenced in 1686, the Qing state initiated multiple empire-wide surveys that first resulted in the compilation of provincial gazetteers. As the project dragged on, in 1728, the Yongzheng 雍正 emperor (r. 1723–35) regulated provincial genealogies to be recompiled every sixty years to renew the primary information for the Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire. This meant that the opportunity to legitimize one's ancestral claim would emerge on a regular basis, also indicating that the compilation project of the gazetteer of the empire would have no end in the foreseeable future.

In fact, the Qing state did not plan to end the compilation project. In 1740, the Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire was finally submitted to the Qianlong emperor with great aplomb. However, as discussed above, its compilation continued as the empire expanded its territory. Over the course of two centuries, the Qing Empire almost constantly sought and officially commended righteousness. As a result, thousands of people were enshrined. After the first Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire was completed in 1743 and printed in 1746, the Gazetteer of the Great Qing Empire was further recompiled as the territory of the empire expanded. The second edition was completed in 1784 and printed and 1790. In 1811, Emperor Jiaqing 嘉慶 (1801–20) issued an edict to declare its recompilation to eventually be completed by his son, the Daoguang emperor, in 1842. Meanwhile, by-products of compilation projects, in the form of collected biographies of a groups of people, were compiled and printed to commemorate historical figures who contributed to the state in certain fields. One such by-product was the Record of Martyred Subjects in the Previous Dynasty, which consisted of cases of loyal martyrs extracted from gazetteers. Over the course of the repeated recompilations, more historical figures were commemorated by the gazetteers,Footnote 33 with emperors requiring local governments to uncover more unnoticed virtues.Footnote 34 During the late eighteenth to nineteenth centuries, in the eyes of the imperial subjects of the Qing, the compilation project of the gazetteer of the empire and the subsequent commemoration of historical righteous figures arguably appeared to be an unremitting state project that legitimized their ancestral claims and granted them privileges.

Once a historical figure was enshrined, the person's descendants had an opportunity to enjoy county/prefecture-wide fame and tangible benefits.Footnote 35 For example, as mentioned above, up to six members of the Bai lineage were granted the post of “keepers of shrine” whose corvée labor was usually exempted. Even if not enshrined, the state project of compiling gazetteers at the national, provincial, and county levels served as significant political and cultural contexts for the emergence of Yuan non-Han ancestries. Having one's ancestry recorded in gazetteers meant honoring descendants in local society. As Joseph Dennis persuasively discusses, local gazetteers could be “public genealogies” that legitimate the ancestral claims and esteemed status of the lineages that successfully have their genealogies recorded in gazetteers.Footnote 36 For example, the Dong 董, Li 李, and Ma 馬 lineages in Neihuang 內黃 County, northern Henan, collectively claim that they are all direct descendants of a Mongolian prince named Temür. Their earliest claim appears in the “notable tombs” (gufen 古墳) section in the 1739 Neihuang county gazetteer:

The tombs of the Five Surnames are located in Cifan Village. It is said that Temür, Lord Wenzhen, Censor, and Vice-Chancellor of the Right in the branch secretariat of Henan, had five sons named Dong, Li, Ma, Guan, and Chen. They were divided into five surnames that were prospering and eminent lineages in Neihuang, having produced members of multiple lineages who passed the examination. Those with the Guan surname migrated to Jiaofu village in Qingfeng County in Zhili, and those with the Chen surname migrated to Yanling County. The other three surnames all reside in Cifan Village.Footnote 37

In 1753, the three lineages established a stele to commemorate the tomb they claimed to be that of Temür, and they engraved an inscription almost identical to the claim recorded in the local gazetteer fourteen years earlier. In doing so, the merging of these three surnames into a fictional lineage was officially authorized by the state. With tombs and steles still existing in the county, the three surnames hold an esteemed position in the county's history.Footnote 38 In varying degrees, the projects of the three surnames and the Bai lineage can be contextualized as bottom-up reactions to the state's project of gazetteer compilation and the subsequent commemorations of righteous figures in history.

Another important cultural background of the emergence of Yuan non-Han ancestries could have been the increasing popularity of epigraphic study among Qing literati scholars. Notably, these cultural endeavors also exerted an enormous influence on gazetteer compilation, especially when the scholars of epigraphic study were deeply involved in such work. The ancestral narratives of the Bai lineage and the three surnames were all recorded in the section of “tombs” (fenmu) in the Dali and Neihuang county gazetteers, respectively. This section often included not only tombs, but inscriptions engraved on the stones.

On many occasions, epigraphical scholars also served as local officials, venturing into the field to investigate epigraphical sources. Consequently, through their publications, they played a significant role in bringing to light numerous local stele sources that otherwise would have remained unknown, including those that were produced in the Mongol-Yuan era. An illustrative example is Bi Yuan, one of the most prolific Qing-dynasty epigraphic scholars and the author of the Epigraphic Records of Guanzhong (Guanzhong jinshi ji 關中金石記). Like many other epigraphical scholars in the mid-eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, Bi also compiled this comprehensive collection of stele inscriptions in Shaanxi based on extensive field research.Footnote 39 He explored both local epigraphy and historical landmarks in Shaanxi with extraordinary vigor during his tenures as Inspector (anchashi 按察使), Provincial Administration Commissioner (buzhengshi), and Grand Coordinator of the province in 1770–79. For example, several steles in the county, such as “Zeng andingjunbo mengjun xinqianbiao” 贈安定郡伯蒙君新阡表 (dated 1318), a Yuan genealogical stele inscription, were included in his Epigraphic Record of Guanzhong. More importantly, in 1756 Bi Yuan even took the initiative of reinstalling this Yuan stele and wrote the calligraphy for it in person.Footnote 40 Similarly, throughout Shaanxi, Bi Yuan occasionally commissioned new steles to commend the steles from previous dynasties.Footnote 41

Concurrently with Bi Yuan, Chen Xuechang 陳學昌, a magistrate of Dali, also put up a stele alongside “Zeng andingjunbo mengjun xinqianbiao,” in 1776, to protect the Yuan stele. It is probably not too farfetched to say that the Bai lineage members were aware of gazetteer compilers’ passion for epigraphic records, which might have inspired them to put up a stele in their ancestral graveyard to commemorate Baiǰu's enshrinement. After all, the steles, both from the previous dynasties and newly-built, were indeed incorporated in the county gazetteer in narrating local history, and the incorporated ancestral records became new historical evidence facilitating the evolution of ancestral narratives.

Conclusion: Ancestry and Ethnicity in Qing and Modern China

Tracing the origin of a lineage in the remote past, the ancestral narrative and kinship cohesion of the Bai lineages fits into the evolution of the Chinese patrilineal kinship organization since the Song. According to Patricia Ebrey, the evolution of the lineage organization eventually incubated the modern “Han” ethnic identity, that is, “imagining the Hua, Xia, or Han, metaphorically at least, as a giant patrilineal descent group made up of intermarrying surname groups.”Footnote 42 Meanwhile, it is worth reiterating that in any sources written before 1937, neither Bai lineage members nor any contemporary observers associated the lineage with any ethnonym. Li Yuanchun's statement attests to this point in a telling manner: “The Bai lineage in Dali is the descendants of the Lord Zhongxian” (大荔拜氏,忠獻裔也). In other words, for Li Yuanchun and his contemporaries, what distinguished the lineage members from their neighbors was the ancestry originated from the Yuan loyal minister, not their ethnic attribution.Footnote 43

Before the early twentieth century, the ethnic boundary for the Bai lineage members and their neighbors seemed ambiguous or even non-existent in the contemporary sources. In the letter to a friend, as we have seen above, Li Yuanchun finds only “Han and Hui Muslims” around Baijiacun in the early nineteenth century. Several decades later, during the Hui Muslim War, the Bai lineage members were obviously Han in opposition to Hui Muslims in the eyes of the Qing military commanders, for no contemporary source refers to “Mongols” in Dali County. Although these accounts do not represent the Bai lineage members’ emic self-perception, the absence of any ethnonym, Menggu, or Han, in contemporary sources may indicate that they accepted being categorized as Han, while proudly demonstrating their Mongol ancestry. The emergence of the notion of race as a species among Chinese intellectuals after the 1910s gave a new attribute, Menggu, to lineage members by juxtaposing them with their Han neighbors.Footnote 44

Indeed, it was only after 1937 that the Bai lineage members were given an ethnic identity by intellectual others or had it imposed on them. In explicating the crucial role that the early Ming imperial enterprise played in the evolution of the ethnonym “Han,” labeling all its subjects “Han” or “Hua” vis-à-vis its northern neighbors, Mark Elliott proposed “[t]hat ethnicity is created transactionally is to say that it emerges only when there is the interaction between two groups.”Footnote 45 This proposal can be applied to the “ethnic” boundary surrounding the Bai lineage after 1937, when they were recorded in the county gazetteer as a group, Mengguzu, vis-à-vis Hanzu.

The self-perception of the Bai lineage before the rise of modern notions of Hanzu and Mengguzu serves as a powerful reminder of the elusive evolution of the Han-ness over the course of the last thousand years of Chinese history. During the tenth to thirteenth centuries, with the Song confronting other such powerful states as the Khitan Liao and then the Jurchen Jin, which often turned into formidable adversaries, a salient cultural identity emerged among Song intellectuals in opposition to these states. Naomi Standen demonstrates that loyalty to the state, zhong, was the primary category determining one's political belongingness and subsequently drawing the boundary between the Song and Liao/Jin realms.Footnote 46 During the Northern and Southern Song, as Shao-yun Yang points out, “ethnocentric moralism” emerged among Chinese academic traditions, especially Daoxue thinkers, which aimed to solidify and perpetuate the Chinese-barbarian dichotomy by asserting “[t]hat the normative world order was one in which the Chinese reigned supreme over all other peoples and that when this supremacy was properly rooted in superior morality, the barbarians could not but recognize and defer to it.”Footnote 47 Nicolas Tackett argues that the notion of “Han” emerged while the Song political elites contextualized their state's existence in relation with the Khitan Liao in the interstate system, while aspiring to retrieve the “lost” Han populace and territory under the Khitan rule.Footnote 48 In each study, the common premise is that Han-ness is a self-perception that requires the existence of culturally and politically distinct Others.

Meanwhile, shedding light on the Hanren 漢人/ Han'er 漢兒 in the Sixteen Prefectures in the Yan-Yun region (Yan Yun shiliuzhou 燕雲十六州) during the Lia-Song-Jin transition, Jinping Wang recently argued that while the “Han-ness” appears in literally collections and dynastic histories, they reflected the political and cultural elites’ top-down idealized vision of imperial subjects. Such an ethnocentric vision was, however, not shared by the Han'er of the Sixteen Prefectures, whose experiences were mainly structured in local epigraphical sources “by social identities configured by wealth, status, locality, and religious belief.”Footnote 49 Wang's discovery aligns nicely with what we have found in the case of the Bai lineage. In local society during the pre-modern eras, a person's political allegiance (if any) did not necessarily constitute the primary factor in defining the person's identity, and in the case of the Bai, “Han” seems to have been an unfamiliar notion to the lineage members before the Republican era, especially when it was compared with their frequently declared self-definition as the descendants of Baiǰu.Footnote 50

Similar to the Han or non-Han identities in the Middle Period, in the case of the Bai lineage, ethnic markers were employed mostly by political and cultural elites such as Li Yuanchun. The contrast between a top-down vision of clearly demarcated ethnic identity and a much more fluid social reality was rather common in the Qing as well. In his study on the conflict between the Bannermen and civilians in nineteenth century Qing China, Mark Elliott has remarked—outside the imperial court where political elites classified imperial subjects with their top-down perception—“Manchu-Han antagonism does not leap out of the historical record and that it does not seem that late imperial Chinese society was wholly riven by ethnic strife.”Footnote 51

It was only during the early twentieth century, through the efforts of Republican intellectuals, that “Han” eventually emerged as a prominent ethnic identity. This identity did not originate from the pre-modern Han-ness but represented new political discourses. Initially imagined as opposed to the ruling Manchus, Han-ness after the last decades of the Qing evolved largely as an ethnicity related to a nation (minzu) during the first several decades of the twentieth century that “comprised a single, homogeneous guozu (nation-state) around the entire, multiethnic body of the Zhonghua minzu,” as James Leibold describes.Footnote 52 In the case of the Bai lineage, while being classified as Han during the Ethnic Classification Project, this new narrative of Han-ness had apparently contravened with their self-perception as the descendants of the Yuan Mongol prince. Rather, it became one of the axes of difference between Mongol (Menggu) and Han minzu, which appears to have facilitated the emergence of their new “Mongol” (Mengguzu) identity vis-à-vis the Han minzu in the groundwork of the contemporary minzu demarcations in PRC. In the same vein, in most cases in Table 1, the apical Mongol ancestors as progenitors of the lineages were commemorated for their undying loyalty to the Yuan state during the late Qing, and the narratives of the Mongol ancestors during the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries have served to rationalize the lineages’ claims to be non-Han today.

As the key institution implemented by the Qing state, the banner system, which “stood for all that was not Chinese about them,” enabled the Manchu identity to endure throughout the Qing era. As this paper has shown, non-Manchu subjects in China proper took advantage of the state project of gazetteer compilation to assert their ancestry beyond the Manchu-Han dichotomy proclaimed by the political and cultural elites.Footnote 53 The legacy of the ancestries authorized by the Qing still lives on today, as shown in Table 1. In terms of its profound impact on identity building or sustenance, the Qing gazetteer compilation project functioned as a “classification project” of some sort, beyond the intentions of the Qing court. Table 1 and the case of the Bai lineage also demonstrate that the result of the Ethnic Classification Project during the twentieth century often conflicts with the ancestry authorized by the earlier imperial state project. Only approximately half of the cases in Table 1 are classified as Mongols (Mengguzu) today. In the Qing gazetteer compilation project, as Li Yuanchun's remarks demonstrate, historical sources played a crucial role in legitimizing one's claim of ancestry. In contrast, in Chinese scholarship during the mid-twentieth century, Stalin's four principles of nationality (common language, common territory, common psychology, and common economic life) became the primary principle in classifying ethnicities.Footnote 54 Indeed, in field surveys in Guizhou and Yunnan conducted to classify minzu in 1954–56, the survey teams lent importance to languages and customs but not necessarily to historical sources that assert ancestry.Footnote 55

However, this does not mean that ancestries authorized by the Qing have no influence today. Rather, as in the case of the Bai lineage, premodern ancestries still act as a basis for lineage identity that contradicts the officially classified minzu registration.Footnote 56 This reality strongly suggests that the classification or identity-making criteria has continued to differ significantly between the state and communities on the ground. The states in Chinese history have repeatedly classified and categorized their subjects, and their classification criteria differed from each other.Footnote 57 North China attracts our attention because it has been, and continues to be, a contested site for claims of identity. In China's two-thousand years of imperial history, hundreds of thousands of non-Han conquerors settled in North China, only to be conquered by the new rulers. However, they did not simply disappear from the historical stage or from local memories. The histories of these non-Han rulers and migrants, as well as the ways in which these histories were remembered, continued to impact the ethnic, cultural, and religious landscapes in North China.

Competing interests

None.