No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 February 2016

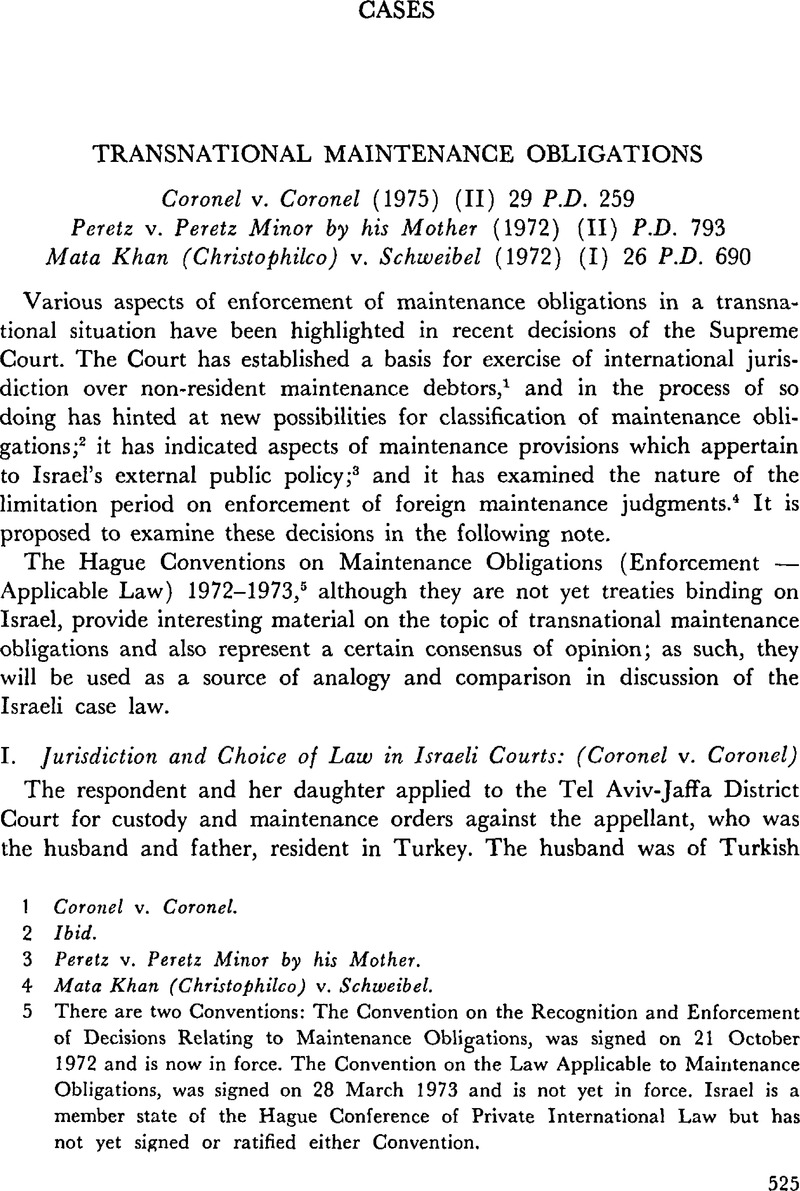

1 Coronel v. Coronel.

2 Ibid.

3 Pereit v. Pereti Minor by his Mother.

4 Mata Khan (Christophilco) v. Schweibel.

5 There are two Conventions: The Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Relating to Maintenance Obligations, was signed on 21 October 1972 and is now in force. The Convention on the Law Applicable to Maintenance Obligations, was signed on 28 March 1973 and is not yet in force. Israel is a member state of the Hague Conference of Private International Law but has not yet signed or ratified either Convention.

6 Capacity and Guardianship Law, 1962, sec. 76(2) (16 L.S.I. 106). The distinction is drawn in the judgment itself at 262.

7 “The Turkish law on matters of marriage and the obligation to maintain a wife was not brought before the Court, and we shall therefore proceed upon the presumption of similarity of laws, and, as a result, we may rely upon the Jewish law which applies to personal matters of Jews living in Israel. Apart from this, it must be remembered that at least the first respondent was resident in Israel at the time of her marriage to the appellant, and it may be that in this case the Turkish law does not apply at all, and all the more so where the couple married in Turkey in Jewish religious form as well” (at 265).

8 At 265–266.

9 At 268–269.

10 At 269.

11 As regards location of the breach of obligation, the Court made no distinction between its ascertainment of the place of breach of the contractual obligation for the purposes of Rule 467 (6) and of the ex lege obligation for the purposes of Rule 467 (9). A similar issue was dealt with by the Supreme Court, in a different context, in an earlier case: in Renvit Import Ltd. v. Langlieb and others (1972) (II) 26 P.D. 12, the Supreme Court held, with regard to an action on a contract which was deemed to have been broken in Germany, that jurisdiction could not be assumed on the basis of sub-Rule 467(9) where it had not been assumed on the basis of the more specifically applicable sub-Rule 467(6); if the contract had been broken in Germany it could not be said that an act or omission had taken place in Israel on the basis of that breach of contract. It should be noted that, as regards breach of a maintenance obligation, application of the proper law of the contractual obligation or of the personal law imposing the ex lege obligation may, in some circumstances, result in a differing location of the duty to pay maintenance and, hence, of the place of breach.

12 See supra text at n. 7.

13 At 266.

14 Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Relating to Maintenance Obligations, 1972, Art. 7(1).

15 At 266–267.

16 At 269.

17 At 269.

18 The Convention plays a ‘passive’ role in that it merely defines the limits within which one state will be prepared to enforce the decisions of a “judicial or administrative authority” in another contracting state; it does not actually lay down the desirable limits of the exercise of international jurisdiction by the contracting states.

19 Verwilghen, , The Explanatory Report on the Conventions on Maintenance Obligations (Enforcement-Applicable Law) 405 [41], para. 50Google Scholar; this explanation clearly reflects a justification for the actual exercise of jurisdiction by the forum of the creditor's habitual residence and not a mere acknowledgment of its existence in practice in the courts of the contracting states.

20 Convention on the Law Applicable to Maintenance Obligations, 1973, Art. 4. The Convention (Art. 7) makes an exception as regards debtors related collaterally or by affinity to the maintenance creditor; and such debtors “may contest” the creditor's request for maintenance “on the ground that there is no such obligation under the law of their common nationality or, in the absence of a common nationality, under the internal law of the debtor's habitual residence”. The Convention (Art. 8) also deals differently with maintenance obligations between divorced spouses, or in case of legal separation or declaration of a marriage as void or annulled; such obligations are determined by the law of the state of the legal decree sanctioning the divorce, separation or nullity.

21 13 L.S.I. 73.

22 Sec. 17 (a).

23 Sec. 17 (b). All other maintenance obligations are governed by the law of the debtor's place of habitual residence: sec. 17 (c).

24 See infra discussion of Peretz v. Peretz Minor by his Mother.

25 Cf., Verwilghen (1972) op. cit. supra n. 19, at 441 [77] para. 138: “…the aim of the maintenance obligation is to protect the creditor. As he is the focal point of the institution, he must be considered in the reality of his daily life and not in the purely legal attributes of his person, as he will use his maintenance to enable him to live. Indeed in this field it is wise to appreciate the concrete problem arising in connection with a concrete society; that in which the petitioner lives and will live”.

26 The debtor's personal law, in imposing an obligation on the debtor bestows a right upon the creditor; in a stable context, in which the parties are established in a society which imposes such an obligation, it is legitimate for the creditor to expect to continue to enjoy the correlative right.

27 See infra at 17–19.

28 See, similarly, where the personal law of the maintenance creditor is the principal connecting factor: Verwilghen, op. cit., at 442 [78] para. 140–141.

29 E.g., De Nicols v. Curlier [1900] A.C. 21; see Dicey, and Morris, , The Conflict of Laws (London, 9th ed., 1973) 647–650Google Scholar; Rule 118: “Where there is no marriage contract or settlement, and where there is a subsequent change of domicile, the rights of a husband and wife to each other's movables, both inter vivos and in respect of succession, are governed by the law of the new domicile, except in so far as vested rights have been acquired under the law of the former domicile” (emphasis by author): the advantage of the rule is that it qualifies the doctrine of mutability which otherwise results from application of the current personal law (the matrimonial domicile) to the distribution of matrimonial property: ibid., at 649.

30 Supra at n. 20.

31 Supra at nn. 22, 23.

32 Levitszky v. Estate of Levitszky (1961) 15 P.D. 2027, 2034. Basel v. Basel, (1962) 16 P.D. 2037, 2042, For a more ambiguous statement which hints at the possibility of a contractual classification for the purposes of determining local jurisdiction, see Basan v. Basan Minor by his Mother (1964) (IV) 18 P.D. 417, 419.

33 The dicta in the case also give weight to this possibility: the suggestion of the Court that Jewish law may be applicable as the governing law in its own right was based on the place of residence of the respondent at the time of her marriage and the Jewish religious form of the ceremony — connecting factors which are only relevant to an ascertainment of the rights to maintenance vested in the respondent by the law governing her marriage and not her or her husband's personal law: see supra n. 7.

34 A similar system of subsidiary connecting factors has been accepted in The Hague Convention on the Law Applicable to Maintenance Obligations, 1973, Arts. 4, 5, 6; however, the subsidiary connecting factors can apply only if there is no obligation of maintenance under the principal connecting factor; see Verwilghen, op. cit., at 443 [79] paras. 142–143.

35 See supra text at n. 7.

36 Dicey, and Morris, , The Conflict of Laws (London, 9th ed., 1973) 436.Google Scholar

37 1972, Art. 1.

38 This “wide” meaning of the term “court” has been employed by an Israeli court in a private international law context. In determining that a Jordanian special court for land settlement was indeed a “court” for the purpose of Israel's Law and Administration (Continuity of Civil Procedures, Enforcement of Judgments and Recognition of Documents) Regulations, 1968, the court held: “According to accepted principles, as they have been expounded on more than one occasion in our courts and according to the Interpretation Ordinance, generally, where there is no special statutory provision providing otherwise, a “court” will include any judicial instance, whatever its appellation. That is to say, it will include any body which is authorized by statute to determine and give judgment upon disputes between parties”. Sheikh Abdul Mo'ati v. Sheikh Sa'ad El Alami (1975) (I) 29 P.D. 17, 21. However, ex contra, the use of the term “court” in the Foreign Judgments Enforcement Law, has been said to exclude administrative tribunals, in contrast with certain bilateral treaties for the recognition of foreign judgments which may include decisions of administrative tribunals: Shapira, , “Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments” (1974/1975) 4 Iyunei Mishpat 509.Google Scholar

39 At 794; Etzioni J. concurred fully with Berinson J., but himself alluded in express terms only to the Family Law Amendment (Maintenance) Law, 1959, at 795; Cohn J. held that there was a presumption that there was a duty on a natural father to support a minor child in foreign legal systems; hence the failure to prove the existence of the obligation under Moroccan law did not affect the child's right to maintenance.

40 Family Law Amendment (Maintenance) Law, 1959, secs. 2(b), 3(b).

41 The Hague Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Relating to Maintenance Obligations, 1972, Art. 6; an exception is made as regards debtors related collaterally or by affinity: see supra n. 20.

42 Verwilghen, op. cit. supra n. 19 at 444 [80], paras. 143–144.

43 Ibid., at 457 [93] para. 175.

44 Batiffol, and Legarde, , Droit International Privé (Paris, 5th ed., 1971) 104.Google Scholar

45 Dicey, and Morris, , The Conflict of Laws, op. cit., at 7, 375, 386.Google Scholar

46 The Hague Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Decisions Relating to Maintenance Obligations, Art. 11, provides that “the application of the law designated by this Convention may be refused only if it is manifestly incompatible with public policy”; since the “law designated” in the Convention includes the law of the forum where there is no foreign obligation, the application of public policy envisaged by Art. 11, must clearly extend to cases where there is some, although inadequate, maintenance obligation under the foreign law: see Verwilghen, op. cit., at 457 [93] paras. 175–176.

47 As it is in The Hague Convention: see supra text at n. 20.

48 See supra text at nn. 21, 22, 23.

49 12 L.S.I. 82.

50 At 695.

51 At 696; Cohn J. noted that Israel was a party to the Convention: K.A. vol. 8, p. 63, but added that he had not examined whether Switzerland was also a party.

52 Israel is not yet a party to the 1972 Convention. See supra n. 5.

53 Art. 13. No definition of “procedure” is given in the Convention and, in view of the differing approaches to the classification of limitations statutes amongst member states, it seems improbable that the Convention could be regarded as replacing local limitation provisions in states which regard their rules on limitation of actions as “procedural”.

54 At 692.

55 At 692.

56 At 695.

57 At 693.

58 Winter v. Kovatz (1963) 17 P.D. 2032, 2037–38; Rosenbaum v. Guli (1964) (II) 18 P.D. 374. Shapira, op. cit., supra n. 38, at 509, 516.

59 Under Art. 46 of the Palestine Order-in-Council, 1922–1947, the Courts have recourse to English common law rules in the absence of any local provisions on the matter in question; see Levontin, and Goldwater, , Rules of Choice of Law in Israel and Article 46 of the Palestine Order-in-Council — Opinion (Jerusalem, 1974, in Hebrew).Google Scholar

60 Nouvion v. Freeman (1889) 15 App. Cas. 1; Harrop v. Harrop (1920) 3 K.B. 386; In re Macartney (1921) 1 Ch. 522. See Shapira, op. cit., at 509, 526.

61 Beatty v. Beatty [1924] 1 K.B. 807; Geiger v. Geiger (1967) (I) 21 P.D. 303, 307–308.

62 An action on the judgment is, in essence, an action to enforce an obligation, the judgment forming conclusive evidence regarding the existence of the obligation: see supra n. 58. Hence the period of limitation on such an action is 7 years: Prescription Law, 1958, sec. 5 (1) (12 L.S.I. 129). See Shapira, , “Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments — Part II” (1976/1977) 5 Iyunei Mishpat 38, 40–41.Google ScholarCf. The limitation period on local judgments in Israel is a 25 year limitation period: Prescription Law, 1958, sec. 21.

63 This transformation in the plaintiff's position is clearly brought home by the rule that a mistake in a foreign judgment does not as such yield a valid defence to an action for enforcement of the judgment whether the action is brought under the Law or at common law. See Geiger v. Geiger (1967) (II) 21 P.D. 495. Where a plaintiff is forced to restate his case ex novo, such a defence clearly becomes viable.

64 At 693.

65 The debtor was subject to the jurisdiction of the Israeli courts before the 5 year period had elapsed and was in default of payment for the entire 5 year period.

66 66 See supra n. 62.