Introduction

Throughout its history, the Ottoman Empire was an agrarian entity, and until its dissolution after World War I agriculture remained the most important sector of its economy, being the state's major source of taxation and the basis of subsistence for the majority of its subjects. However, scholarly interest in those who engaged in agriculture has been less than adequate. Research on Ottoman peasantsFootnote 1 has been overshadowed by a general fascination with wars, elites, bureaucracy, and the workings of the Ottoman state. Even when peasants have managed to make an appearance in the literature, historians have usually portrayed them as the passive recipients of state policy or as mere pawns in power games involving actors such as the central state, local functionaries, provincial magnates, and international powers. Likewise, it has been commonplace to argue that Ottoman peasants were mostly acquiescent towards the state and that in the Ottoman Empire there were no mass peasant revolts comparable to those in western Europe, China, or Russia.

In fact, there were several significant rural uprisings, instances of popular resistance, and protests in the Ottoman Empire in the nineteenth century as well as in earlier periods. The Balkan, Arabic-speaking, and to a lesser extent, Anatolian provinces of the empire were significantly affected by rural unrest from the mid-nineteenth century onwards.Footnote 2 When autonomous peasant action was too obvious to be denied, historians have often searched for other actors who might have instigated the uprisings in question. For example, most nineteenth-century peasant insurrections in the Balkans have been considered as predominantly nationalist uprisings and nationalist urban intellectuals as their main actors. Moreover, the denial of the agency of peasants is closely related to the propensity to overemphasize the centrality of the state in Ottoman social formation, itself a remnant of the impact on scholarship of the modernization approach.

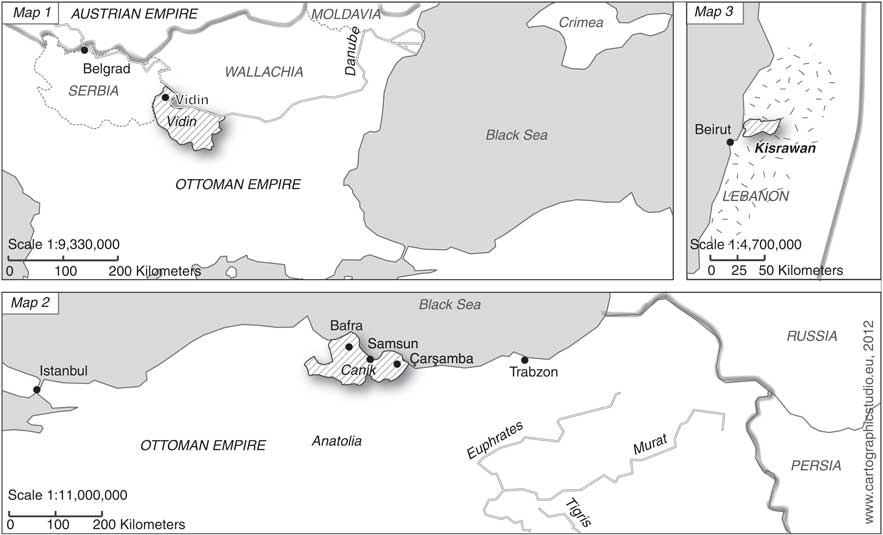

On the other hand, in parallel with the increasingly vocal critique of the modernization theory, an alternative literature on the Ottoman peasantry has emerged over the past twenty-five years.Footnote 3 Such work has focused on the question of peasant revolt mostly in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and has usually striven to find out why there was no uprising of the peasantry, although more recently peasant protest and rebelliousness during the late Ottoman period has begun to be researched more extensively.Footnote 4 This article is intended to contribute to the emerging literature on nineteenth-century peasant revolt in the Ottoman Empire by analysing three of those revolts, namely the ones in Vidin in the northern-central Balkans, at Canik in northern Anatolia, and at Kisrawan in Mount Lebanon. The revolts will be examined mainly from the point of view of peasant attitudes and the methods of protest the peasants employed in the course of conflict.

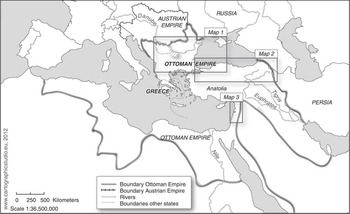

Figure 1 The Ottoman Empire in the mid-nineteenth century.

I have chosen those three cases for three reasons. First, the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Arab lands constituted the three geographic and cultural regions of the empire, and I hope that the analysis of the three cases will produce results that can, at least to some extent, be generalized across all Ottoman territories. Secondly, one of the cases is quite different from the other two in terms of social relations of production. Relations of production in Vidin and Kisrawan were predominantly feudal, whereas in Canik cultivators were small-holding peasants who had a significant degree of control over the land and the production process, and that difference matters to the argument of this article. Thirdly, the ethno-religious dimension of relations between cultivators and their adversaries were different in the three cases. In Vidin, the cultivators were Christian and the landlords Muslim. In Canik, however, while the magnates were Turkish the cultivating class was composed of Greek, Armenian, and Turkish peasants. In Kisrawan, Maronite Christian peasants rose against their overlords, also Maronite Christians. Therefore Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan had quite diverse features in terms of relations of production and of ethnicity. By choosing the three cases here, I hope to be able to show that despite different combinations of production relations and ethno-religious factors, there were parallels in peasant attitudes and strategies as well as methods of protest.

The article begins with a brief account of the Tanzimat (literally “reorganization”) that set the stage for the peasant revolts, and there follows a section on the three revolts discussing their background, the revolts themselves, and their outcomes. I have used primary as well as secondary sources for Vidin and Canik, and relied on the existing literature for Kisrawan. The cases of Vidin and Kisrawan are relatively well known, but the Canik conflict has not been studied extensively. In addition to the intensive use of primary sources for two of the three cases studied, the main goal of the article is to throw new theoretical and interpretative light on all three instances of peasant revolt.

In the theoretical section, I shall discuss the concept of “moral economy” and especially its repercussions in rural contexts, and will argue that the moral economy of peasants can be defined as the combination of subsistence ethics, a notion of what is just and what is not, and a tendency to valorize labour. I shall further argue that moral economy is an inherently useful tool for understanding the behaviour of the Ottoman peasants during the three cases of social conflicts analysed in this article.Footnote 5 I shall discuss the actual forms that peasant protest took in those cases, namely good organization, the absence of support from outside, rare and considered use of violence, refusal to pay what they considered unfair taxes, steadfastness or a tendency to radicalize, and preferring to deal with central instead of local authorities. The subsequent section of the article discusses peasant revolt in relation to the Tanzimat reform programme. The argument there is that the revolts were not simply negative reactions to the Tanzimat, as often claimed in the literature; instead, they were possible only within the framework of the reformed Ottoman polity that the Tanzimat itself brought about. Moreover, peasants’ “misunderstandings” of the reforms through rumour did not stem from ignorance nor lack of access, but were intentional acts intended to reinterpret and radicalize the Tanzimat in accordance with peasant aspirations.

MID-NINETEENTH-CENTURY OTTOMAN REFORMS

About the middle of the nineteenth century, the Ottoman state initiated an ambitious reform programme, known as the Tanzimat, which is the name given to both the decree of the Ottoman Sultan read aloud publicly on 3 November 1839, and the subsequent reforms. According to the historiographical convention, the Tanzimat period lasted from 1839 to 1876, when the first Ottoman constitution was promulgated. The Tanzimat reform programme was intended to change various aspects of the Ottoman state and society. The decree itself promised four things: first, it guaranteed the security of life, honour, and property to Ottoman subjects; secondly, it declared equality between Muslim and non-Muslim subjects; thirdly, it promised to establish a regular system of taxation and to abolish the tax-farming system; and fourthly, it underlined the necessity of a well-functioning system for military service which would include non-Muslims.

The reforms brought progress in relation to the first two promises, although by and large attempts to implement the last two failed. On the other hand, change effected by the Tanzimat reforms went beyond the framework defined in its decree. In the first place, the state grew both quantitatively and qualitatively during the mid-nineteenth century as the number of bureaucratic offices and public servants grew exponentially after 1839.Footnote 6 Moreover, the state began to concern itself with areas that had hitherto been considered outside its purview, such as urban planning, health care, and mass education. Secondly, the growth of the state apparatus was followed by a gradual democratization of the decision-making processes. Councils were established with real powers at both central and provincial levels, with members of provincial councils being elected. The new councils, albeit mostly under the control of local notables – something which emerges clearly in the Vidin and Canik cases described here – provided an accumulation of experience in representative politics which later helped a more democratic political process to emerge.

A third effect of the Tanzimat was that it entailed a far-reaching campaign of codification.Footnote 7 Modern laws were enacted, some of which were original and some adapted from abroad. Among the most important of those laws were the Imperial Penal Code (1840, 1851, and 1858), the Imperial Land Code (1858), the Civil Code (1860s–1870s), and the Law on Provincial Administration (1864).

Fourthly, giant steps were taken towards instituting equality before the law. The Ottoman Nationality Law (1869) dissolved the system of compartmentalization of Ottoman subjects according to religion and provided a framework of common nationality for all. The Tanzimat state therefore presumed the equality of non-Muslim subjects and tried to enforce it. A further edict promulgated in 1856 explained and confirmed the rights of non-Muslims. Finally, the reform programme set in motion the gradual and less visible but unmistakable trend towards secularization. The establishment of modern, secular courts alongside the kadi courts, the inclusion of secular elements in the new laws, and the gradual erosion of the Muslim versus non-Muslim hierarchy all worked towards the secularization of the Ottoman polity.

The reform programme profoundly influenced politics and society in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-nineteenth century, both through those of its provisions and promises which were fulfilled, and those which went unfulfilled. As I shall demonstrate below, the Tanzimat played an important role in the three peasant revolts discussed here. The peasants in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan did not reject the reforms and they certainly were not indifferent to them. On the contrary, they were acutely aware of their importance and reacted to them accordingly.

THE VIDIN REVOLT, 1849–1850

In the nineteenth century, the sub-province of Vidin was an important economic centre of the northern-central section of the Ottoman Balkans. Its importance derived mostly from the role of the town of Vidin as a port on the river Danube, a busy trade route. Yet Vidin's rural areas seem to have followed a different trajectory from that of some of the other parts of Ottoman Bulgaria that were enjoying an economic revival in the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 8 In rural Vidin, a feudal land regime called gospodarlık, based on a complex set of relations of exploitation, including corvée, and legal and social obstacles to land ownership by Christian cultivators, was in effect.

Notwithstanding the pertinent questions asked by some Bulgarian Marxist scholars,Footnote 9 scholarly study of the land regime and revolts of Vidin seems to be stuck somewhere between a Bulgarian nationalist perspective, which reduces peasant protest during late Ottoman rule to an anachronistic notion of “national awakening”, and a Turkish nationalist historiography that focuses on foreign incitement and local abuses by landlords in an otherwise fair society.Footnote 10

The unrest in Vidin began in April 1849 in two villages near the town itself, when the villagers attacked the subaşı (steward of the landlord). The insurgency soon spread to other villages in the area and could be subdued only with some difficulty. The magnitude of events in 1849 was enough to force the government of Serbia, at the time an autonomous principality, to close its border with the Ottoman Empire proper.Footnote 11 A year later, a much bigger uprising broke out, which began in three villages as clashes between the peasants and the beylikçis (collector of the tax on livestock) but spread very rapidly to other villages.Footnote 12 Up to 10,000 people from villages around Vidin and the districts of Lom and Belgradçık joined the insurgency.Footnote 13 At first, 6,000 peasants gathered in the vicinity of Vidin. The rebels cut all communication between the town and the villages and then secured a strategically important pass. After that, between 3,000 and 4,000 peasants surrounded the town of Belgradçık. A few days later, peasants from dozens of villages took to the mountains in the vicinity of their villages.Footnote 14

Figure 2 Vidin and the Ottoman Balkans (Map 1), the Canik district and northern Anatolia (Map 2), and the Kisrawan region (Map 3, with the borders of modern Lebanon in the background), in the mid-nineteenth century.

The governor sent out a group of negotiators composed of Muslim and Christian notables and Christian clergy to listen to the rebels’ demands and to try to persuade them to give up, but the rebels refused to talk to anyone from Vidin. Apparently, the peasants trusted neither the Christian clergy nor the notables from the town. Despite the Porte's orders for moderation, the landlords took complete control of the local council and dealt with the revolt very heavy-handedly, organizing irregular troops who attacked the rebels with disproportionate force.Footnote 15 There were large-scale massacres of peasants in open fields, on the roads, and in villages. Moreover, even the Christian residents of Belgradçık, who did not take part in the revolt and did not join the peasants who surrounded their town, suffered massacre and pillage.Footnote 16

The central state initially adopted a relatively impartial approach. Following the massacres of Christian peasants and townspeople, the governor of Vidin was removed and various local functionaries were arrested. In contrast, the local councils in the region were dominated by landlords who not only wished to subdue the revolt, but wanted to punish the rebels with reprisal killings. The local councils of the towns of Vidin and Lom organized attacks on rebels outside the town limits, although the garrison commander at Vidin and the mayor of Lom explicitly opposed such action.Footnote 17 The central government was aware of landlord domination of the local councils, and soon after the revolt decided to appoint four officials from the capital to certain of the local councils in the area.Footnote 18 Moreover, in late 1850 the central government appointed the treasurer and the president of the local council of Vidin in order to be able to supervise the council and the local authorities effectively.Footnote 19 A government envoy was sent to the area the following year to lead an enquiry into the condition of the inhabitants and the proceedings of the local authorities.Footnote 20 The complaints and demands of the peasants were taken into consideration, and in late 1850 they demanded that the communes of Sahra/Vidin, Lom, and Belgradçık be combined into a single district to be governed by a kaymakam (sub-governor). The Porte accepted their demand and appointed Hacı Mehmet as the kaymakam of the new district. Hacı Mehmet was a Turkish officer who had accompanied the peasant deputation to the capital after the revolt.Footnote 21

The first government attempts to resolve the matter also reflected the initially moderate attitude of the central state. According to the first proposal drafted after the revolt, the cultivators were to take over the land from landlords after paying a certain sum to the state, while the landlords would receive state bonds as compensation.Footnote 22 However, three years after the first revolt, and a year and a half after the original government proposal, it became apparent that the villagers did not really want to pay for the land.Footnote 23

Moreover, there were differences between the attitudes of and solutions proposed by local governors and central bureaucrats. Eventually, the Special Council met in the capital in June 1852, exactly two years after the second revolt, and decided that the landlords should keep the demesne land, which was not allocated to cultivator households but held under the direct control of the landlord, and the peasants should pay the regular tithe and other taxes as well as rent to the state.Footnote 24 The proposal presented a truly disagreeable option for the peasants. Previously, they had refused to pay the state and become independent peasants mostly because they also wanted to take over the demesne lands. The government now imposed on the peasants a plan that would not only not give them the demesnes but would in fact render them merely tenants on imperial estates. The partial and unrealistic second plan apparently brought the affair to deadlock. The land question in Vidin dragged on for a long time and the area became part of independent Bulgaria, which was formed in 1878.

In Vidin, a cultivating class who depended on land for livelihood and a non-cultivating class for whom land was the major source of income came together in a setting where agricultural productivity was low, capital and investment scarce, and possibilities for technological innovation limited. Without some increase in economic productivity, landlords were in no position to offer any meaningful economic compromise. Furthermore, in addition to the combination of sheer force and police authority, the core of the relations of domination and exploitation between the two classes was the system of ethno-religious exclusion. Non-Muslim cultivators were not allowed to hold arable land independently in the region, making ethnicity an important factor contributing to their discontent. Because of that dependence on the politico-legal exclusion of Christian cultivators from landowning, that is to say, because their ability to siphon out and appropriate surplus depended on political power, landlords were equally reluctant to accept anything that would give the cultivators control over the land.Footnote 25 In a manner that showed the degree of their dependency on land, during the subsequent process they consistently refused to give up the demesne land. Similarly, the cultivators’ main demand during and after the revolt was for land, their sole source of subsistence. Cultivators were unwilling to negotiate any settlement that would not give them full control of land, and to acquire what they demanded they engaged in protest in a number of ways.

AGRARIAN CONFLICT IN CANIK, 1840s–1860s

Canik is the historical name of the central Anatolian region on the Black Sea coast and in the mid-nineteenth century it was one of the sub-provinces of the province of Trabzon. At that time, the majority of the population were Muslim, but with a significant presence of Greek Orthodox and Armenian populations.Footnote 26 The main economic activity in the region was agriculture, although the rising volume of imports increased the importance of the Samsun port and customs revenue in the second half of the century.Footnote 27

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Canik, like many other parts of the empire, was under the political, military, and economic domination of a magnate family, the Caniklizades. From their quite humble origins, the Caniklizade family became a local dynasty, and in the 1770s and 1780s extended their influence to the rest of the Black Sea coast as well as eastern Anatolia, securing high-ranking bureaucratic positions for its members. In subsequent decades, their rivalry with the Çapanoğlu family created significant problems and, as is well known, the dynasty came to an end in 1808 after throwing in their lot with the opponents of Selim III.Footnote 28

Figure 3 Tanyus Shahin (Tanios Chahine), head of the Kisrawan peasant commonwealth; bronze bas-relief portrait by Halim el Hajj. Onefineart.com

The vacuum created by the elimination of the Caniklizades was filled by a lesser magnate family, the Hazinedars, who controlled a number of bureaucratic posts in the first half of the nineteenth century.Footnote 29 For example, in 1840 Osman Pasha was the governor of Trabzon, his brother Abdullah Bey was governor of Canik, his younger brother governor of Bafra, and his son Süleyman, who was actually cognitively disabled, governor of the town of Çarşamba.Footnote 30 When Osman Pasha died in 1842, Abdullah Bey was appointed governor of Trabzon to succeed him.Footnote 31

A few years later, in 1848, at a time when an individual who was not a Hazinedar was governor of Trabzon, Hacı Ahmet Pasha of the Hazinedars, who was then governor of Canik, set out to make himself independent of the governor in Trabzon.Footnote 32 Thus, the Hazinedar family not only monopolized all high-level bureaucratic posts in Canik and Trabzon, they were also able to act quite independently in administrative and commercial matters. For example, the governor of Canik, if he happened to be a member of the Hazinedar family, would continue to reside in the town of Çarşamba, the town where the main palace of the family was located, although the official seat of the governor of Canik was in the town of Samsun.

It seems that the Hazinedar family had lost their control over key offices by the late 1850s, although that did not mean that they lost their economic power also. On the contrary, they were able to extend their right to collect taxes into claims about property over wide tracts of arable land. The Tanzimat required the abolition of tax farming and the establishment of a modern, centralized tax-collection system under the direct control of the treasury. Tax reform was implemented in the central provinces at first and then gradually extended to provinces more distant from the capital. Although the Tanzimat taxation system was introduced to Canik only in 1857, it had been known about since as early as 1847.Footnote 33 As the tax farmers of Canik, the Hazinedars, along with a number of lesser magnates in their entourage, foresaw that the new, Tanzimat-style taxation system would remove their tax-collecting privileges and deny them access to land, so they tried to pre-empt the new system's establishment. They now claimed to own the villages which had constituted their tax farms, although the practical demands of the local magnates were at odds with their grandiose claims of ownership. At least initially, the magnates’ manoeuvres were too limited to be considered a land grab, and in most cases what they were doing amounted to demanding twice the regular tithe, or an additional tax.Footnote 34

The cultivators in question, unlike those in Vidin and Kisrawan, were independent peasants who organized themselves and made their own decisions about production, and it seems that those two factors were significant in making the Canik conflict more protracted and less violent than the ones in Vidin or Kisrawan. On the other hand, they did not bring about a qualitative difference in peasant attitudes and actions during the course of the conflict. The peasants saw in the claims of magnates the beginning of a process that would convert them into tenants on land they had always considered as their own, so they resisted the claims from the onset. So it was that, around the middle of the nineteenth century, a general agrarian conflict began in Canik that pitted a large cluster of rural direct producers and a group of local magnates against each other.Footnote 35

The conflict actually began in 1848 and its intensive phase lasted for twelve years. The peasants who lived in villages claimed by magnates as their private estates refused to make the extra payments demanded by the magnates. The Greek Orthodox patriarchate was involved from the beginning because the largest group among the peasants were Greek, along with Armenians and Turks. There were several attempts by the magnates to force the peasants to fulfil their alleged obligations, and by the peasants to evade them. At times during the course of the conflict the magnates were able to get the peasants imprisoned, and in one instance some peasants were kept in prison for almost a year.Footnote 36 For their part the peasants, at times collectively and at times village by village, continued to send petitions complaining about the pressure exerted upon them by the magnates and by local authorities. The central state began by attempting to keep its distance and leave the resolution of the conflict to the local authorities as far as possible, explicitly authorizing the local councils of Canik and Trabzon to deal with the conflict. However, as the peasants knew full well, almost all members of the two councils were among those who were making claims over the peasants.Footnote 37 Not surprisingly then, the councils intervened to vindicate the claims of the magnates, and made rulings about matters in 1853 and 1855.Footnote 38

The Porte put forward a concrete proposal for the first time in early 1854.Footnote 39 Following that, several central state organs, including the Grand Vizier's office, the Supreme Council, and the Commission on Landed Estates all became involved in the dispute. At some time late in 1857, the government appointed an envoy to go to the region and collect the accumulated debt owed by the peasants to their landlords,Footnote 40 although there then followed a number of contradictory edicts issued by the Grand Vizier's office.Footnote 41 The tensions intensified when the Tanzimat tax reforms were declared applicable to Trabzon province in 1857.Footnote 42

In April 1858, a ferman was sent to the governor for the payment of claims in arrears. The collection was apparently accompanied by acts of cruelty, which led some peasants to abandon their villages, while more than 800 peasants assembled around the town of Samsun in July 1858 to present their grievances to the governor.Footnote 43 In response to the continuing disturbances, the Supreme Council in Istanbul took the matter up again. The ad hoc committee formed within the Supreme Council reached a decision about the disputed land in December 1859.Footnote 44 Although the committee's ruling recognized the claims on peasants made by the magnates, it tried to provide some protection for the peasants. The committee therefore ruled that since the main complaint of the peasants concerned the possession of land, land which was either occupied unlawfully or unoccupied should be auctioned, and the auctions to be open to Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Although the ruling seems to have calmed the tensions for a while, it did not solve the problem completely. In at least two waves, in 1867 and 1868, large numbers of peasants tried to emigrate to Russia, and there is evidence that peasant discontent continued as late as into the 1880s.Footnote 45

In Canik, a significant number of peasants were involved in the protracted agrarian conflict there. For example, in the first emigration attempt, the number was estimated by the governor at around 3,000 people, while the British Consul put the number of peasants affected by the disturbances at around 4,500. Throughout the conflict, the peasants employed different strategies and methods of resistance and protest, including petitioning, refusal to pay taxes – which was the most direct strategy and the most frequently employed – assembly, and emigration. I shall discuss the strategies and methods of the Canik peasants below, along with those of the peasants in Vidin and Kisrawan.

KISRAWAN PEASANT REPUBLIC, 1858–1861

One of the most important popular revolts in the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire took place in the Kisrawan region of Mount Lebanon during late 1850s. Since its incorporation into the empire in 1516, the combination of a non-military feudal aristocracy,Footnote 46 the distinctive geography that both separates the area from its surrounding regions and creates internal divisions,Footnote 47 and ethno-religious diversity gave Lebanon a peculiarity within the Ottoman polity that lasted until the very end. One consequence of its peculiarity was the extensive autonomy Lebanese rulers enjoyed vis-à-vis both the Ottoman governorFootnote 48 and the Sultan. The amīrs were at the head of a complex hierarchical network of families, which was preserved through strict feudal titles and ritual practices.Footnote 49 Crucially, the elite was a single, non-sectarian group and up until the mid-nineteenth century the most important social demarcation in Lebanon was not religion but class.Footnote 50

Kisrawan was situated in central Lebanon to the north-east of Beirut. It produced a range of crops, including grain, but from the seventeenth century onwards the cultivation of mulberry trees and sericulture became the most important agrarian activities.Footnote 51 From the end of the eighteenth century Lebanon underwent a slow but effective commercialization linked to the expansion of sericulture and maritime trade along the Mediterranean coast.Footnote 52 That trend, which reached its zenith in the nineteenth century, led to market-based and financial surplus extraction mechanisms to replace non-economic coercion in parts of Lebanon.Footnote 53 In contrast, the feudal landowners of Kisrawan, the Khazins, had to rely ever more on non-economic coercion for surplus extraction.

After enjoying a long period of prosperity and strong autonomy, the Khazins were in an evident decline owing to economic and political factors. The amīr's demands for more levy and the Khazins’ desire to take a larger part of silk production prompted them to turn to Beiruti moneylenders for credit. As a result, the Khazin households accumulated debts, and by the 1830s and 1840s many among them were impoverished.Footnote 54 In addition, the Khazins gradually lost control over the Maronite Church.Footnote 55 Their decline led the Khazins to strive to fight off their economic woes, on the one hand by wasting money to improve their social and political standing, and on the other by increasing the pressure they put on Kisrawani peasants. The peasants in Kisrawan were already working and living under harsh conditions, being forced to work under written sharecropping contracts, most of which concerned the growing of mulberry trees and included surrendering half their revenue, in addition to paying a number of dues in labour, cash, and kind. The peasants were often obliged to borrow money from middlemen and moneylenders to meet their cash needs, which tended to create cycles of indebtedness.Footnote 56

The Kisrawan Revolt of 1858–1861 is better known than most other late Ottoman peasant revolts, but in the literature, despite some notable exceptions,Footnote 57 the incident still seems to be overshadowed by the sectarian clashes of 1860 that engulfed parts of Lebanon and Syria.Footnote 58 Makdisi argues that different narratives about sectarian violence in Lebanon converge in seeing the homogeneity of religious community or sect as an obstacle to modernity and sectarian violence as ahistorical, unchanging, and endemic.Footnote 59 That essentialist understanding of sectarian violence opposes ethno-religious difference and class affiliations and construes a necessary contradiction between the two.Footnote 60 A more promising perspective would consider ethno-religious difference as a social force, the impact of which on class relations can be discerned only through the empirical study of concrete cases, not a priori assumptions. I shall discuss the question further in the relevant section below.

The immediate context of the Kisrawan revolt was created by the feudal offensive against peasants in the late 1850s, the Khazins’ struggle to bring down the Christian kaymakam, and the economic depression of 1857 caused by the Crimean War.Footnote 61 Under the dual kaymakamate regime, Kisrawani peasants, as co-religionists of their sheikhs, were not given the right to elect their representatives, and that left the peasants with no regular channels to voice their complaints and demands. Thus, sharing the same religion as their landlords worked in their particular case to the disadvantage of the peasants.

The unrest in Kisrawan began in the autumn of 1858 with organizations of the peasants in a number of villages, but became a fully fledged revolt only when, at a gathering of village deputies in early 1859, the peasants chose as their leader a farrier, Tanyus Shahin. The peasants then declared a republic – or commonwealth (jumhūriyyah) – and demanded full equality with their feudal masters. Thus, they went well beyond demanding an end to extra dues and the excessive practices of their landlords. What they demanded was nothing less than the end of feudalism in Kisrawan. The Khazins reacted with intransigence at first, refusing even the moderate demands of the peasants.Footnote 62 In time, the rebels increased their power and determination, and expelled Khazin families from Kisrawan. They replaced the feudal rule of the Khazins with a republican self-rule, which even came to be recognized de facto by the authorities and the Church.

In the meantime, however, sectarian tensions were rising in Mount Lebanon. The Kisrawanis made no attempt to export their revolt, yet both the Druze and Maronite peasants in the neighbouring regions were influenced by what had happened in Kisrawan and showed signs of agitation. The Druze sheikhs of Shuf responded by provoking sectarian clashes in order to contain peasant unrest, and in the ensuing civil war the Druze won a quick victory.Footnote 63 The Kisrawanis were only briefly involved in the civil war and Tanyus Shahin acted cautiously and coherently throughout.

The peasant republic was brought to an end by a Maronite notable supported by the Ottomans, the Maronite Church, and European states.Footnote 64 The post-1861 settlement created an autonomous Ottoman province under the guarantee of the European powers. Although the règlement organique explicitly abolished feudalism and the associated privileges of feudal families, the Ottoman government incorporated them into the new administration, appointing their members to important posts.Footnote 65 The Khazins, likewise, were restored by incorporation into the local bureaucracy. On the other hand, the revolt achieved most of its goals. Despite the efforts of the first two governors to restore Khazins to their land,Footnote 66 the peasants managed for the most part to keep the land as theirs. Even the notable who had defeated Tanyus Shahin did not dare suggest a return to the status quo ante. The peasant regime had acquired so much legitimacy that the restoration of the old order was out of the question.Footnote 67 Shahin himself was appointed āmir of part of Kisrawan.

THE MORAL ECONOMY OF OTTOMAN PEASANTS

In this section, I shall develop the argument that the Ottoman peasants in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan acted within a framework of moral economy, and that their moral framework to a large extent determined their attitudes and actions during the course of agrarian conflicts in the mid-nineteenth century. However, since the concept of moral economy has been used in the literature to mean different things and in different contexts, a theoretical detour is necessary in order to clarify how the term should be understood in this article.Footnote 68

The term “moral economy” was developed by E.P. Thompson in an article in which he set out his opposition to the view that crowd action in general in the early modern era, and riots in particular, should be seen as instinctive, compulsive, and spasmodic rather than conscious and rational.Footnote 69 Instead, he argued that in the food riots of eighteenth-century England there was a strong legitimizing notion that gave a clear purpose and a degree of coherence to the apparently spontaneous and chaotic actions of the crowd:

It is of course true that riots were triggered off by soaring prices, by malpractices among dealers, or by hunger. But these grievances operated within a popular consensus as to what were legitimate and what were illegitimate practices in marketing, milling, baking, etc. This in its turn was grounded upon a consistent traditional view of social norms and obligations, of the proper economic functions of several parties within the community, which, taken together, can be said to constitute the moral economy of the poor.Footnote 70

James C. Scott has borrowed the concept in his studies on south-east Asian peasants in the modern era, redefining it as the combination of subsistence ethics and the principle of reciprocity. Scott defines subsistence ethics as the ethics of those peasants who live very close to the margin of subsistence and for whom a single lean harvest might spell disaster. As a result, those peasants have, over generations, developed certain technical arrangements to produce the most stable yield, and such peasant communities have generated social mechanisms to prevent certain families from going below the subsistence level.Footnote 71 The principle of reciprocity as it concerns the moral economy of peasants is related to the relations between peasants and those who control resources, namely the lord, the landlord, the king, the elites, and so on. As Scott proposes, in almost all rural class relationships peasants regard certain practices, most importantly meeting their basic material needs, as the duty of the upper classes.Footnote 72

Scott's notion of moral economy is different from Thompson's in two senses. First, the historical and sociological contexts differ.Footnote 73 In Thompson's account those who act upon their moral economy are the urban poor; in Scott's they are peasants. Moreover, the eighteenth-century context of moral economy as described by Thompson was formed by “paternalism”, nobility's rage and suspicion towards merchants, and the transformation of the English state apparatus. It is indeed clear that full-scale rebellion by peasants against direct appropriation by the elites in a bid to preserve their subsistence (Scott) is different from an urban crowd's rioting selectively against those whom they see as responsible for interventions in the market for grain and rising prices of bread (Thompson). The contextual difference has conceptual implications as well: Scott's “subsistence ethic” as one of two components of moral economy is a universal, whereas Thompson's idea of moral economy is a more context-bound conceptual category.Footnote 74

The other difference concerns reciprocity as the second component of moral economy. It is at this point that Scott's broadening of the concept of moral economy seems problematic in two respects. One implication of the juxtaposition of subsistence ethics and reciprocity is that the peasant evaluates the demands on his or her labour and surplus according, not to the amount taken away, but to the amount remaining after such extraction. For example, a peasant would react less strongly to a rent of 40 per cent in a good year than to a rent of 20 per cent in a bad year. According to Scott, therefore, a peasant is more concerned about whether basic material needs are respected than about how much of a crop might be extracted by outside agency.Footnote 75

It is problematic to argue that peasants are not interested in what proportion of the crop is extracted from them and concern themselves only with what is left, because that implies that the peasant legitimizes expropriation as long as subsistence ethics are respected and reciprocity is established by the observance of elite obligations. Viewed like that, peasants’ concerns are narrow and the implication is that they do not attribute any intrinsic value to their labour. As I shall try to show below, however, valorizing labour expended upon land is indeed a major part of the moral economy of peasants. Michael Adas, contrary to Scott, suggests that peasants have ethics that drive them to view everything extracted from them as illegitimate, regardless of the amount they keep after extraction.Footnote 76 The subsistence ethics, then, determine the “red line” of extraction by upper classes beyond which peasants rebel.

A second problem is that undue emphasis on the notion of reciprocity might lead to a blurring of the distinction between what peasants believe about the obligations towards them of the ruling class, and what they strategically claim. Such blurring might give way to scholarly denial of the capacity of peasants for independent reasoning, for example in cases where peasants are considered royalists or naive monarchists because they apparently believe that justice would emanate from the king (or tsar or sultan) and protect them. The idea is discussed in detail below, but here it is enough to say that it would contradict Scott's own general view of peasants, which considers them to be notably calculating in their dealings with the upper classes.Footnote 77 It is indeed necessary to distinguish between what obligations peasants really expect the upper classes to fulfil and what they actually claim as part of their strategy to limit extraction. Too strong an emphasis on reciprocity might preclude making that distinction.

THREE ELEMENTS OF MORAL ECONOMY

The critical points raised above notwithstanding, I think that the concept of moral economy can still be applied to rural contexts and peasant protest, not least in an attempt at elaboration and clarification. Below, I shall try to elaborate the concept of moral economy on the basis of three elements: subsistence ethics, a notion of justness, and valorizing labour.

One of the most important contributions of the concept of subsistence ethics is to enable a satisfactory answer to be offered to the question of why peasants usually stick to custom and strive to conserve the existing order of things, even when confronted with what might prove to be favourable change. Based on subsistence ethics, peasants tend to adopt the principle of “safety first”, and will generally prefer arrangements including stability, protection of current position, and low risk to those involving change, some probability of improvement of position but high risk.Footnote 78 A striking example is recounted in Tolstoy's Resurrection, where peasants on one of the nobleman Nekhlyudov's estates reject an offer that would make them the effective owners of the land.Footnote 79 Such behaviour on the part of peasants is no mindless reflex.Footnote 80 When faced with change, peasants often choose to retain established custom, because traditional arrangements respect minimal expectations of subsistence. When peasants stick to tradition, it is often because they fear that a new balance might be disadvantageous to them or even threaten their subsistence.Footnote 81

In the Ottoman revolts, the role of subsistence ethics had much more to do with an attachment to land as the source of livelihood than with any expectation of reciprocity. In Vidin, the cultivators made clear, both during the insurgency and afterwards, that they were not interested in negotiations about their dues, but wanted to abolish all claims by landlords on the land the peasants cultivated, including the demesnes.Footnote 82 Moreover, they refused to pay for the land even in the context of a plan that would have “emancipated” them. Such an attitude might, of course, have reflected the cultivators’ ideas about whom the land belonged to in the first place. In an oft-quoted anecdote, a group of Russian serfs responded to their landlord, who proposed to emancipate them and rent part of his estate to them: “We are yours, but the land is ours”.Footnote 83 In an analogous manner, by revolting against the landlords and by refusing to pay for the land, the cultivators in Vidin perhaps said to the landlords: “We are not yours”; and to the state: “and the land is ours too!”.

In Canik, the actual demands of the local magnates who claimed estate ownership were quite limited. Why then did the peasants resist and risk paying a heavy price? First, because a claim of ownership of land was present, albeit not emphasized, in the magnates’ demands, the peasants might have believed that extra taxes would be only the first step in what was likely to be a series of demands. Secondly, the pressure that extra demands put on peasant livelihood is also determined by the amount of the surplus. Ceteris paribus, that in turn is a function of the average amount of land available to each peasant household. The shortage of arable land in Canik, the relatively small strips that peasant households cultivated, and the low levels of grain productionFootnote 84 might have led to fierce and determined peasant resistance to any further claims on their surplus. Therefore, the attachment to their land as part of their subsistence ethics seen among the peasants of Canik might be considered one of the driving factors behind their protest and resistance.

A notion of justness – meaning simply a sense of what is just and what is not – could be seen as the second component of peasant moral economy. The notion is rather vague; sometimes it appears in a legal context (legal vs illegal), sometimes the context is politico-legal (legitimate vs illegitimate); the principle also appears in loosely defined contexts (acceptable vs unacceptable). It applies to a range of upper-class practices, but most importantly to taxation. Peasants and townsfolk have been very clear about taxation from a moral economy point of view. As discussed above, peasants tend to deplore all forms of extraction, but they react particularly strongly when certain boundaries that define the “just” are not respected by the upper classes. That is perhaps why resort to a tax strike was the main form of lower-class protest in so many different cases. In a well-known example from late sixteenth-century France, the tax privilege of the nobility was the single most important cause uniting peasants and townsfolk in revolt in the town of Romans.Footnote 85 In the Ottoman Empire, the Canik peasants emphatically rejected the double taxation imposed upon them and, for as long as twelve years, were able to withhold payment of taxes which they regarded as illegitimate. Kisrawani peasants particularly resented the landlords forcing them to pay the miri tax and extra levies due on land.

The third component of the moral economy of peasants is their valorization of their own labour. Fervent opposition to corvée played an important part at Vidin as well as in many mid-century rural disturbances in the Ottoman Empire. More importantly, the objection to corvée seems not to have been simply about staying above the subsistence threshold. The peasants apparently attached a particular significance to labour, and especially to hard labour performed in the past. The Canik peasants argued that the land in question consisted of territory that had been rocky and rough but had been turned into arable land through the intensive labour and great expense of the villagers.Footnote 86

It should be noted that their emphasis on the historic cost of their labour was similar to their opposition to corvée and different from some of the tactical steps they took during the conflicts. For example, peasants were aware of the power of written documents and so they presented legal documents in support of their claims. In destroying such documents too, they showed equal consciousness of the documents’ power. Sixteenth-century French peasants destroyed land registers called terriers,Footnote 87 Russian peasants frequently destroyed seigneurial and tax records.Footnote 88 Similarly, Vidin rebels destroyed notarized documents issued by the local courts which attested to peasants’ obligations to landlords.Footnote 89 In both presenting and destroying documents, peasants were not acknowledging the legitimacy of what was written on those papers but instead making a practical intervention. In contrast, when they made claims to landlords or state officials about hard labour expended in the past, that was less a tactical move than an expression of their sense of moral economy.

STRATEGIES AND FORMS OF PEASANT PROTEST

An analysis of the Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan revolts reveals that there were significant commonalties and convergence in terms of strategies and forms of peasant protest in the three cases. In all of them the rebels were well organized and benefited from good planning. In Vidin, the 1850 uprising erupted on the same day in different localities, a sign of prior organization and coordination on the part of the rebels. Militarily, their strategy was similar to that of the peasants who had rebelled in Niš in 1841; both groups tried to isolate the area by controlling the main route to Istanbul.Footnote 90 In Canik, 500 peasants, ethnically diverse and apparently from different villages, came together and made a deal with a ship's captain to take them to Russia. The Kisrawan peasants were excellently organized both during the revolt and during the period of self-rule. After the Khazins were forced out, the peasants did not arbitrarily loot, but confiscated Khazin property in an organized way. Likewise, the demesnes of the Khazins were neatly divided up among the peasants.Footnote 91 The rebel government in Kisrawan was democratic not only in principle, as seen in the creation of a peasant commonwealth, but also in practice. The leader, Shahin, was elected twice, once as the sheikh shabāb of the village of Ajaltun, then as the spokesperson for all rebel villages. In documents, he made references to the authority of the people and of republican government. He ran the government with the assistance of a council formed by elected village wakīls, who had executive and judicial functions.Footnote 92

Another thing common to all three revolts was that no significant outside support was present before, during, or after them. That is important because both contemporary adversaries and observers, such as elites, consuls, or bureaucrats, and historians alike have had difficulty in coming to terms with independent peasant action.Footnote 93 In relation to the Vidin revolt, incitement by the Serbians has been referred to, but really the Serbian government did not provoke the rebellions, nor did it assist the insurgents once they had rebelled.Footnote 94 In fact, the Serbians even turned away the hundreds of families who flocked to the border.Footnote 95 In Canik, the government accused agents provocateurs and foreign propaganda, specifically the Russian consul, and certain peasants who desired to take possession of the land of the would-be migrants. It is interesting that the claim about foreign incitement was brought up not by local functionaries who would have had more information about it, but by central officials.

The range of theories about who incited or assisted the Kisrawani rebels is even wider. Contemporary observers and historians have pointed to different actors, such as townsmen,Footnote 96 the Ottoman authorities,Footnote 97 the Maronite Church,Footnote 98 the kaymakam, and the French Consul, all of whom have been variously accused of being responsible for instigating or supporting the revolt, setting an example to the rebels or, at least, turning a blind eye to what went on. Even the French Revolution was brought up as having inspired the revolt.Footnote 99 In fact, none of those agents or factors was involved. Towns joined the revolt well after it was under way.Footnote 100 Given the usual approach of the Ottoman authorities to unruly peasants, it is not difficult to imagine the disgust they felt at the Kisrawani rebels, who seemed to challenge every accepted notion about an individual's proper place in the world, and they soon initiated a foodstuffs embargo on the rebel republic before Fuad Pasha's arrival in 1860.Footnote 101 It is true that the Khazins’ control over the Church had diminished significantly, the lower clergy of the Maronite Church being mostly poor, with even the bishops being of humble origin.Footnote 102 Yet, the Church as an institution and property owner was still on the side of law and order, and tradition.Footnote 103 Finally, the Kisrawani peasants did not need the French Revolution to be inspired: “The similarity of the demands of Maronite peasants, who were exposed to French education, and the largely illiterate Druze peasants suggests that the ideas of the French Revolution were not necessary to inspire such revolts.”Footnote 104

Despite the allegations to the contrary made by state officials and landlords, the rebels in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan resorted only very rarely to violence, and always directed it against selected targets. In contrast, as has frequently been the case throughout history, the peasants’ adversaries did not refrain from indiscriminate violence in their response. In both the Vidin uprisings, the villagers attacked only carefully selected targets, such as the landlords themselves, and their stewards and tax collectors. In contrast, as we have seen, the troops led by local councils committed indiscriminate massacres in villages and towns. The only instance of violence on the part of the Canik rebels was beating up a soldier, whereas the magnates did not hesitate to have some peasants imprisoned for months.Footnote 105 Hundreds of peasants did indeed assemble near Samsun in what must have been a rather threatening manner, but they did not try to force their way in.Footnote 106 Kisrawan rebels used violence quite cautiously, and mostly to force Khazins to leave the land; there were only a few Khazin casualties during the insurrection.Footnote 107 In contrast, during the previous strife among the Khazin households the two camps had committed massacres against their own and the rival faction's peasants.Footnote 108

The peasants in all three cases engaged in direct action by refusing to pay taxes. In Vidin, the rebels refused for seven years to pay the land rent. Acting within their framework of moral economy, they did not agree to extractions they considered illegitimate, and in a more pragmatic way their action undermined the economic power of the landlords, who were already under financial pressure. The Ottoman government was twice compelled to order the collection of the money owed, so the Vidin peasants’ withholding of tax was also an act of resistance against the state. Tax strikes were the most important part of the Canik peasants’ protest; at different intervals, they too refused to pay taxes they regarded as illegitimate.

The refusal to pay tax had important implications for the ownership of the land, because the local magnates’ claims for rents and taxes were based on their claims of ownership. When the peasants refused to pay, they rejected such claims by landlords and asserted their own ownership of the land in question. The two tenets of the peasant moral economy, attachment to the land and the notion of justness, were thereby interconnected. In Kisrawan, having to pay the taxes demanded by landlords was one of the main peasant complaints, for they clearly believed that the burden of those levies on the land should be shouldered by the landlords. As a result, the peasants opted for a radical solution and completely ejected the landlords. The peasant republic subsequently established did not tax the peasants, nor did the authorities try to tax them. Thus, as I have argued in relation to the concept of moral economy, a notion of justness played an important role in the formation of peasant attitudes to taxation in the Ottoman cases.

There was also a common tendency to radicalize demands and methods of protest. The Kisrawani peasants began with milder demands, but underwent an evident radicalization, as, after the resumption of negotiations with the Khazins, the peasants made demands that were more radical than the ones they had made in the first round.Footnote 109 That was probably related to a fuller realization of their power, which urged them to eject the Khazins in toto.Footnote 110 To reach their goals, the rebels used all the weapons at their disposal, including “the French card”.Footnote 111 Just like the rebels at Vidin, who used proximity to Serbia as a strategic asset, and the Canik peasants, who benefited from a nearby sea route to Russia, the Kisrawanis did not hesitate to employ anything that could give them an edge in their anti-feudal struggle.

The Kisrawan peasants were not alone in opting for radical solutions. During the negotiations after the revolt, the Vidin rebels repeatedly refused plans that the officials considered moderate and wanted a final solution to their grievances. They did not want to pay to buy the land that they considered as their own, and consistently demanded that the landlords vacate all land, including the demesnes. The Canik land conflicts were protracted, and the peasants made the same claims about land and taxation from the late 1840s to the 1880s.Footnote 112 When other tactics, such as petitioning, refusing to pay dues, and sending representatives to Istanbul, did not seem to work, they radicalized their protests. They gathered in large numbers in an unmistakeably threatening way around the town where the governor resided. When that did not work, they did not hesitate to resort to the ultimate weapon, emigration to a foreign country. As early as 1858, the peasants had threatened to emigrate to the Crimea if their grievances were not addressed.Footnote 113 At some time late in 1867, the inhabitants of the villages on the Kurşunlu estate and some 600 families attempted to flee to Russia, and in the second half of 1868, 500 people agreed with a certain Captain Ömer to emigrate to Russia by sea.Footnote 114 Thus, throughout the conflict, the peasants employed all the assets they had to try to conclude the dispute in their favour.

THE ROLE OF ETHNO-RELIGIOUS FACTORS

Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan had quite diverse features in terms of ethno-religious relations between peasants and landlords. In Vidin, the cultivators were Bulgarian Christians and the landlords were Turkish Muslims. The exclusion of non-Muslims from landholding was one of the main pillars of the prevalent socio-economic system, and the so-called gospodarlık, which was contrary to not only the mid-nineteenth-century reforms but also to the pre-reform legal stipulations concerning landholding, was able to survive thanks to that exclusion. Ethno-religious difference played a role during the Vidin revolt too, with some urban Christians who took no part in the revolt being massacred, and one of the avowed reasons for the central state's refusal to distribute land to peasants after the revolt was that it would be dangerous to give land to Christians in a region bordering Serbia. Finally, the correspondence between ethno-religious and class-based demarcations and the state's failure to introduce a viable solution to the problem encouraged peasants to voice their demands in increasingly ethnic language. That, in turn, made it possible for the agrarian conflict in Vidin to contribute to the Bulgarian independence movement in the medium term.

In Canik, all the magnates were Turkish but the cultivating class included Greek, Armenian, and Turkish peasants. There, ethno-religious demarcation played a triple role. Before the new taxation system was introduced, the local magnates had made pre-emptive claims on peasant land. Although some Turkish Muslim peasants were involved in the conflict, most of the peasants were Greek or Armenian. The magnates were able to sustain their claims for a substantial period of time because, even in the reformed Ottoman polity, non-Muslim peasants were more vulnerable than Muslim ones to upper-class pressure and extortion. Secondly, the Greek Orthodox patriarchate played an active role in transmitting peasant demands and representing them during the course of the conflict. Thirdly, emigrating to Russia might have stood out as a viable alternative because most of the peasants involved were Greek, so had religious ties with Russia.

Despite the presence of Druze peasants in those areas of Mount Lebanon of which Kisrawan is a part, the revolt that this article has dealt with occurred among the Maronite peasants and was against their Maronite overlords. In Kisrawan therefore, the two sides of the agrarian conflict shared the same ethno-religious background, so that there the class conflict stood out more clearly than in the other cases. Moreover, both the Ottoman government and the foreign powers, which were extremely sensitive about social conflicts having an ethnic dimension, were apparently less alarmed by a conflict between Christian landlords and Christian peasants, and that might have given the rebels relatively more room for manoeuvre. Finally, as seen above, the spread of the revolt in Kisrawan to other parts of Mount Lebanon was prevented by sectarian clashes between Christians and the Druze.

In all three cases then, ethno-religious factors played a part. However, what was crucial was not religion per se, even less any particular religion, but the fact that there existed a demarcation defined in religious terms. Class relations and ethno-religious difference were intertwined in complex ways and there can be no ready-made assessment of whether the religious differences increased the intensity and visibility of class conflict. Ethno-religious difference acted as a social force which became part and parcel of class divisions and struggle under certain circumstances. In Vidin, as in many areas of the Ottoman Balkans, the correspondence between ethno-religious difference and class divisions had the two-fold effect of inflaming class conflicts while gradually giving them a nationalist overtone. In Canik, ethno-religious differences between magnates and most peasants made the peasants more vulnerable to pressure from the magnates, although that simultaneously gave them additional opportunities to organize and resist. In Mount Lebanon, ethno-religious difference was incorporated into class struggle either by its presence, as in Shuf, or its absence, as in Kisrawan. The Kisrawani peasants initially enjoyed the advantages of its absence, but the peasant republic was eventually suffocated by ethnic clashes in neighbouring areas. On the other hand, despite the varying impacts of the different configurations of ethno-religious relations on the contexts and trajectories of the agrarian conflicts discussed in this article, peasant attitudes and strategies and methods of protest before and during insurrections were remarkably similar.

PEASANT MONARCHISM?

One of the significant convergences in the attitudes of rebels in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan was a tendency to prefer to deal with central authorities rather than local ones and a favourable attitude to the symbolic authority of the Sultan. In Vidin, the governor responded to the revolt by sending a group of negotiators composed of Muslim and Christian notables and Christian clergy to listen to the rebels’ demands and to try to persuade them to give up. The rebels would not talk, because they refused to negotiate with locals and would deal only with officials from Istanbul.Footnote 115 They also refused to recognize the jurisdiction of the local council in the region, which was evidently under the control of landlords. The rebels always formulated their demands in the language of allegiance to the Ottoman state. They positioned themselves as antagonists to the authority in Vidin, but not to that at Istanbul. It is indeed striking that, when the governor or the council of Vidin sent orders after the revolt, the peasants refused to obey them, saying that they would take orders only from “their” kaymakam, who was appointed by “their” Sultan!Footnote 116 Against claims on their labour as well as their land, they referred to themselves as “padişah reayası” (literally, “the Sultan's peasants”). No such official term existed in the Ottoman Empire, but the cultivators’ coining of it suggests that they perceived their status as being similar to that of peasants in Russia, where before the abolition of serfdom in 1861 “state peasant” was a legal category different from the “seigneurial peasant”.Footnote 117

The view of the Canik peasants was quite similar, for more than once they declared that they trusted neither the members of the Trabzon nor those of the Canik councils, since the majority of their members were magnates with claims on peasants.Footnote 118 Indeed, the peasants demanded throughout that their cases be heard and settled by representatives of the parties in Istanbul instead of in Samsun or Trabzon. Despite the radical nature of their demands and their actions against the local landlords, the Kisrawani rebels did not consider themselves as being in revolt against the Ottoman Empire. Rather, they invoked traditional metaphors about Ottoman justice and benevolence.Footnote 119 In the light of all these points, it might well be asked whether the peasants of Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan had an essentially positive predisposition towards the Sultan. Did they think that the officials in Istanbul would be fairer-minded than the ones in their own respective regions? Did they believe that their cases might be more favourably resolved if the Sultan himself could be made aware of their plight?

Similar questions have been asked in the literature concerning Russian peasants.Footnote 120 Some historians have labelled Russian peasants as naive monarchists because they apparently believed in the justness of the Tsar as opposed to “evil” nobles, and because many of them sent petitions to the capital in the hope of alleviating their suffering, and their rebellions were often carried out in the name of the Tsar.Footnote 121 It has been argued to the contrary that Russian peasants claimed to be rebelling in the name of the Tsar only in order to give their actions legitimacy and to avoid some of their consequences.Footnote 122

Monarchism, or royalism, has been discussed also in the context of the attitude of French peasants to the French Revolution. Charles Tilly argues that, although the peasant participants in the counter-revolutionary movement of the Vendée joined the “God and the King” battle cry of the rebels, that did not make them automatically royalist.Footnote 123 Tilly's account suggests that blind loyalty to the monarchy was hardly a significant factor pushing the peasants into counter-revolution. Further, he objects on methodological grounds too to the search for peasant royalism in the counter-revolution. For Tilly, it is problematic to search for a standard and common mentality that led French peasants to join the counter-revolutionary insurrection. Instead, he supports shifting the emphasis to the sociological background of the Vendée.Footnote 124

It seems that in all three of the Ottoman cases, the peasants’ favourable attitude to the Sultan entailed more than a desire to limit the level of state repression should the revolt fail. Indeed, the peasants wanted not only to evade some of the possible consequences of a failed insurrection, but also to increase their chances of success. In that they were quite pragmatic. In a similar way to the Russian peasants who were aware of how local justice was dispensed, they “were simply following the correct legal channels and appealing to higher authority over the heads of the local officialdom”.Footnote 125 That interpretation is confirmed by the fact that the rebel peasants in Canik and Vidin explicitly expressed their distrust of the members of the local councils and of some of the local functionaries. The peasants did not manifest naive monarchism or any other kind of naivety; rather, they were aware of the power structure in the local councils and of the tendencies of local officials, so they chose to appeal to higher (preferably the very highest) authority in the hope of bypassing local authorities. The positive attitudes of peasants to the monarchs therefore often had more to do with their realistic evaluation of the circumstances and the local balance of power rather than any sort of uninformed belief in the ultimate fairness of the monarch.

TANZIMAT, RUMOUR, AND PEASANT REVOLT

The Tanzimat was an essential component of the context which paved the way for the peasant rebellions in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan, for it figured predominantly in the way the rebels perceived the conflicts and configured their demands. The connection between the Tanzimat and the revolts is important for us too in that it draws attention to yet another similarity in peasant protest, and helps dismiss scholarly claims of the passivity of the peasants in the face of Ottoman state power.

The land regime in rural Vidin was based on the systematic exclusion of Christians from land ownership. Perpetuating that ethno-religious exclusion, however, became increasingly contradictory in the face of the Tanzimat principles that promised equality before the law. The peasants were aware of it, as they unequivocally demanded that the Tanzimat should be established in “Bulgaria” as in other provinces.Footnote 126 In Canik, the disturbances broke out before the Tanzimat programme began to be applied in the Trabzon province.Footnote 127 In order to pre-empt the forthcoming decision to abolish tax farming, the tax farmers, feeling the threat of disenfranchisement under the reformed polity, set out to subsume peasant land into their private estates. That was their ultimate goal, but in the meantime they attempted to force the peasants into double taxation.

The Canik peasants therefore reacted to a situation in which they were not only unable to benefit from the Tanzimat reforms, but in which they would actually end up worse off than they already were before reform. The involvement of the Tanzimat in social conflicts is perhaps best illustrated by the case of Kisrawan. In a petition containing their grievances, the rebels made explicit references to the edict of 1856.Footnote 128 The Tanzimat aroused among the commoners the hopes of equal taxation and of abolishing feudalism. Moreover, as Makdisi argues, in presenting their remonstrance the commoners mimicked the Tanzimat: a new representation couched in the moral authority of an idealized past.Footnote 129

On the other hand, the peasants in Vidin, Canik, and Kisrawan seem to have interpreted the Tanzimat in a more radical way than its architects would have wanted. The Vidin peasants argued that the Sultan had given the land to them and, as we have seen, even “invented” a new legal category. A certain Mehmed Emin Ağa was sent to Canik to survey the disputed land and transmit two pieces of official correspondence to local authorities. He instead misrepresented the contents of the correspondence to the peasants as being in their favour and tried to extort money from them. It is remarkable that the peasants believed him so easily when he claimed that the state had confirmed the land as being theirs, and even that the rent they had paid so far would be reimbursed.Footnote 130 The Kisrawan peasants were similarly ready to believe that the central state had much to offer them with the Tanzimat. They interpreted the civic equality clauses of the reform edicts, already ambiguous enough in themselves, as providing social equality and full religious emancipation.Footnote 131

Why did the peasants perceive the decrees of 1839 and 1856, or lesser forms of official documents, to be more in their favour than they actually were? Was it childish ignorance, as contemporary authorities and many historians have argued? Was it the incitement of ill-disposed individuals who wanted to abuse the peasants’ ignorance? Or was it sheer fabrication on the part of the rebels, as suggested by Shahin's letter that talked about an imperial order for the liberation of Christians and which mentioned the Treaty of Paris in an attempt to strengthen the rebel argument about the abolition of feudal privileges?Footnote 132 Why did the Canik peasants so easily believe the existence of an order concluding the disputes in their favour? Did the Vidin peasants really believe the rumours that the Sultan had given them the land?

Such attitudes on the part of the Ottoman peasants paralleled those of Russian peasants who “invariably ‘misunderstood’ laws to be more in their interests than intended”,Footnote 133 or of Indian peasants during whose revolts rumours played a crucial role. Indeed, the role of rumour in peasant insurgency has been most studied and best illustrated in relation to the behaviour of the Indian peasants. In particular, Ranajit Guha's work has been influential in establishing the perception of rumour as a subversive mode of rebel communication.Footnote 134 That is a relatively recent perception, growing up alongside the emergence of a new perspective on “the masses” in history, which has revised an established tendency to deny any rational calculation and autonomous action on the part of lower classes in times of violent conflict.Footnote 135

Rumour is the anonymous and unverifiable collective talk of a group of people. Due to its ambiguity, anonymity, and transitivity, it is open, free, creative, and dynamic. As such, rumour has played an important role in various cases of peasant insurgency in different parts of the world, an aspect of it which has led Guha to assert that “rumour is both a universal and necessary carrier of insurgency in any pre-industrial, pre-literate society”.Footnote 136

In the literature, there are two views of the role of rumour in peasant insurgency. The first underlines that rumour is a reaction to certain news, which is often about the actions or intentions of the upper classes or the state. Rumour thus enables peasants to come to terms with important news in a collective manner. As such, it is reactive, emotional, spontaneous, and impulsive.Footnote 137 The second view, on the other hand, focuses on the more constitutive aspects of rumour. Rumour simultaneously prepares the ground for an insurrection and provides legitimacy to the insurrectionary movement. Moreover, it unifies peasants on the basis of common complaints and demands. According to the second approach, rumour is proactive, intellectual, planned, and attentive.Footnote 138

Based on evidence from the three mid-nineteenth-century peasant revolts in the Ottoman Empire, this article subscribes to that second view of rumour. Although one can detect in rumour an element of psychological relief as a way of dealing with significant change imposed from above, I believe that it played a more constitutive political role in Ottoman peasant uprisings, in three respects.

First, the great majority of peasants were illiterate and so, of course, were unable to read legislation or any other written document. Although in peasant society there were individuals who could read, such as village headmen, communal leaders (kocabaşı), notables (çorbacı), priests, and imams, the relationship between literate and “ordinary” peasants was hardly straightforward or unproblematic, as the evidence from the Vidin and Canik uprisings shows. In Vidin, extortion by urban-based Christian clergy and notables was one of the sources of complaint from Christian peasants.Footnote 139 In addition, there were reports that the deputation of Christian notables and clergy who were supposed to represent peasant interests in the capital were under heavy influence from the authorities.Footnote 140 In Canik, the name of the peasant representative, a certain Panayotaki, who was working for the Greek Orthodox patriarchate, came up in allegations concerning fraud and extortion.Footnote 141

Thus, the peasants could not fully and directly rely on the literate members of their communities to report and interpret written communication truthfully. In addition, the nature of official correspondence and legislation aggravated the problem. However clear and definitive the authors might have wanted official documents to sound, such documents issued by the nascent modern state were imprecise, vague, and at times contradictory. They included important loopholes, and occasionally technicalities were in discord with the underlying principles. When information about legislation, edicts, and decisions trickled down to peasants, it opened up room for interpretation contrary to the authors’ intentions. The complicated nature of the relations between illiterate and literate peasants on the one hand, and the technical deficiencies of the legislation on the other, created a vacuum that could be filled by rumours.

Second, rumour should not be seen only as a means by which quick-witted peasants took advantage of the imperfections of legislation. It was probably the basic way in which peasants embellished legislation with extra material, misconstrued official documents, and “created” new legal categories; and rumour unified peasant rebels around a common cause. As collective conversation,Footnote 142 rumour enabled the peasants to agree on common demands in situations of conflict and crisis, otherwise a very difficult task. When the Vidin peasants claimed that the Sultan had given them the land, it was not so much a fabrication as a method of formulating a basic demand and unifying the peasants around that demand.Footnote 143 Similarly, the Kisrawani peasants’ assertion that the Tanzimat called for full social emancipation of peasants was essential to legitimizing revolt in the eyes of the rebels.

Third, rumour helped the peasants to bypass local authority and formulate their demands for reception at the imperial level. I have discussed above how it was that peasant attempts to neutralize local authorities by no means reflected naive monarchism. Instead, they were part of a carefully crafted strategy intended to minimize the consequences of the exceedingly unfavourable local balance of power. That strategy could not be conceived without rumour. Indeed, the apparent belief in the justness of the Sultan, as opposed to untrustworthy local landlords and functionaries, could be sustained, at times despite contrary evidence, only through rumour. Without rumour, the “just Sultan” could not give land to peasants, nor could he abolish all feudal dues.

Thus, the peasants’ “misunderstanding” of government edicts, decisions, intentions, and official correspondence did not stem from ignorance nor from lack of access due to language problems.Footnote 144 The peasants were indeed collectively defending their moral economy and striving to obtain what they believed they deserved. Theirs was political action with more or less clear goals, and it applied to both official pronouncements and less important documents relating to conflicts, and to the constitutive texts of the Tanzimat, namely the imperial decrees of 1839 and 1856.

CONCLUSION