Crossref Citations

This article has been cited by the following publications. This list is generated based on data provided by

Crossref.

Watt, Amber M.

Elshaug, Adam G.

Willis, Cameron D.

and

Hiller, Janet E.

2011.

Assisted reproductive technologies: A systematic review of safety and effectiveness to inform disinvestment policy.

Health Policy,

Vol. 102,

Issue. 2-3,

p.

200.

MacKean, Gail

Noseworthy, Tom

Elshaug, Adam G.

Leggett, Laura

Littlejohns, Peter

Berezanski, Joan

and

Clement, Fiona

2013.

HEALTH TECHNOLOGY REASSESSMENT: THE ART OF THE POSSIBLE.

International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care,

Vol. 29,

Issue. 4,

p.

418.

Park, Sung-Yeon

Yun, Gi Woong

Holody, Kyle

Yoon, Ki Sung

Xie, Shuang

and

Lee, Sooyoung

2013.

Inside the blogosphere: A taxonomy and framing analysis of abortion weblogs.

The Social Science Journal,

Vol. 50,

Issue. 4,

p.

616.

Hodgetts, Katherine

Hiller, Janet E

Street, Jackie M

Carter, Drew

Braunack-Mayer, Annette J

Watt, Amber M

Moss, John R

and

Elshaug, Adam G

2014.

Disinvestment policy and the public funding of assisted reproductive technologies: outcomes of deliberative engagements with three key stakeholder groups.

BMC Health Services Research,

Vol. 14,

Issue. 1,

Street, Jackie M.

Callaghan, Peta

Braunack-Mayer, Annette J.

and

Hiller, Janet E.

2015.

Citizens’ Perspectives on Disinvestment from Publicly Funded Pathology Tests: A Deliberative Forum.

Value in Health,

Vol. 18,

Issue. 8,

p.

1050.

Niven, Daniel J.

Mrklas, Kelly J.

Holodinsky, Jessalyn K.

Straus, Sharon E.

Hemmelgarn, Brenda R.

Jeffs, Lianne P.

and

Stelfox, Henry Thomas

2015.

Towards understanding the de-adoption of low-value clinical practices: a scoping review.

BMC Medicine,

Vol. 13,

Issue. 1,

Wortley, Sally

Street, Jackie

Lipworth, Wendy

and

Howard, Kirsten

2016.

What factors determine the choice of public engagement undertaken by health technology assessment decision-making organizations?.

Journal of Health Organization and Management,

Vol. 30,

Issue. 6,

p.

872.

Milazzo, Adriana

Mnatzaganian, George

Elshaug, Adam G.

Hemphill, Sheryl A.

Hiller, Janet E.

and

Lambalk, Cornelis B

2016.

Depression and Anxiety Outcomes Associated with Failed Assisted Reproductive Technologies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

PLOS ONE,

Vol. 11,

Issue. 11,

p.

e0165805.

Harris, Claire

Ko, Henry

Waller, Cara

Sloss, Pamela

and

Williams, Pamela

2017.

Sustainability in health care by allocating resources effectively (SHARE) 4: exploring opportunities and methods for consumer engagement in resource allocation in a local healthcare setting.

BMC Health Services Research,

Vol. 17,

Issue. 1,

Tursunbayeva, Aizhan

Franco, Massimo

and

Pagliari, Claudia

2017.

Use of social media for e-Government in the public health sector: A systematic review of published studies.

Government Information Quarterly,

Vol. 34,

Issue. 2,

p.

270.

Cook, Nigel

Mullins, Anmol

Gautam, Raju

Medi, Sharath

Prince, Clementine

Tyagi, Nishith

and

Kommineni, Jyothi

2019.

Evaluating Patient Experiences in Dry Eye Disease Through Social Media Listening Research.

Ophthalmology and Therapy,

Vol. 8,

Issue. 3,

p.

407.

Saylam, Ayşegül

and

Yıldız, Mete

2022.

Conceptualizing citizen-to-citizen (C2C) interactions within the E-government domain.

Government Information Quarterly,

Vol. 39,

Issue. 1,

p.

101655.

There has been increasing focus on the use of HTA to inform both investment in and disinvestment from technologies. Understanding the social aspects of a health technology may be particularly important when considering disinvestment from an entrenched and valued technology or service. However, the cultural beliefs and values associated with a technology may be difficult to measure or assess. Furthermore, in the same way that social meaning and “best case” promise of a new technology may work against evidence of safety, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness, strongly held beliefs, values, and interests with respect to an existing technology may frustrate disinvestment initiatives (Reference Elshaug, Hiller, Tunis and Moss11).

In the context of disinvestment, in-depth analysis of the socio-political environment using theoretical frameworks is important but empirical collection of community perspectives may also be useful, if potentially expensive and time-consuming (Reference Braunack-Mayer, Street and Rogers2;Reference Facey, Boivin and Gracia12). Web2.0 (interactive social media) offers an opportunity to inexpensively collect a range of community views (Reference Street, Braunack-Mayer, Facey, Ashcroft and Hiller23).

Through its universal health insurance program, Medicare, the Australian Government subsidizes assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures, including in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), for all citizens and permanent residents (Reference Doherty6). The Medicare scheme sets a level of reimbursement for a particular medical service. In Australia's fee for service healthcare system, doctors in the private sector may charge above this level of reimbursement, resulting in a “gap” payment. With ART services primarily private sector based, such “gap” payments are dependent on: procedure undertaken, treatment stage and clinic billing policy. However, ART services are also covered by the Extended Medicare Safety Net (EMSN), which can be accessed once an individual's medical costs reach a threshold amount in a given financial year (Reference Doherty6). The Australian Government has periodically entered into policy debates around the introduction of access criteria for IVF services, most notably in 2005 when age and cycle limits were proposed but not enacted. However, after a change of government, the 2009/2010 Federal budget included a cap on EMSN rebates for ART services to counter purportedly inappropriately high provider fees. This policy change took place in a context where the Australian Government provides a “baby bonus,” a one-off payment awarded to all new parents on the birth of a child.

We have analyzed relevant peer reviewed literature, media articles and associated on-line public response, to provide insight into the socio-political implications of disinvestment from ART public funding in Australia. This method is based on the assumption that the media both reflects and forms community views and that it was the primary information source for the public of the proposed disinvestment. The objective of this study was to examine whether such an analysis provides a useful view of sociopolitical aspects of a technology and in particular, community beliefs and values with respect to disinvestment from publicly funded health care.

METHODS

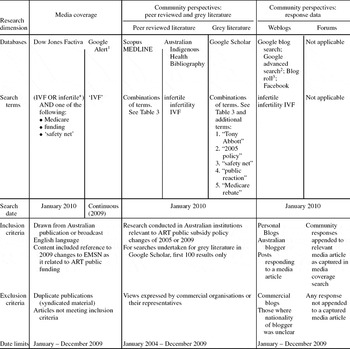

Peer reviewed, gray literature and published documents detailing media and community response to the 2009 proposed changes to ART public funding were sourced as summarized in Table 1. Searches and culling were carried out by one researcher (SH) based on criteria developed by all authors.

Table 1. Summary of Methods and Sources Used in the Study

Note. *truncation character; 1 Google Alerts are email updates of the latest relevant Google results based on own choice of topic” 2 within domains of blogspot.com and blogger.com; 3 List of blogs relating to infertility, pregnancy and adoption, http://www.stirrup-queens.com

Media Coverage

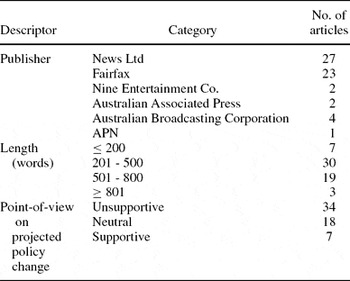

Print and on-line media articles were sourced for 2009 through the Dow Jones Factiva database (http://global.factiva.com/), which can only be searched using free text, and from a 2009 Google alert (http://www.google.com/alerts). Search terms and exclusion/inclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1. In total, 363 media articles were identified. Articles are frequently syndicated, with the same article appearing in multiple newspapers. Duplicates of syndicated material and papers which did not fit the criteria were eliminated; the characteristics of selected articles are described in Table 2. A full list of included articles can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 3, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011028.

Table 2. Summary of the Characteristics of Media Articles (n = 59) Selected for Analysis

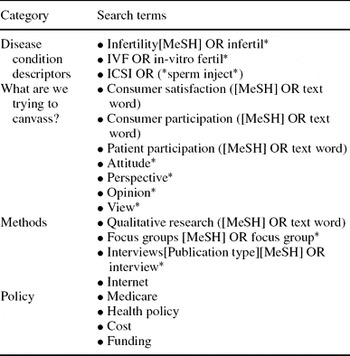

Peer Reviewed Literature

Scopus and Medline bibliographic databases were searched to identify peer reviewed studies providing community views on proposed public funding policy changes (see Tables 1 and 3). Including articles published January 2005 to December 2009 captured discussions relating to proposed policy changes in 2005 and the lead up to policy change in late 2009. Views expressed by commercial organizations or representatives of commercial organizations were excluded. Use of Scopus permitted the search to be limited to research conducted at Australian institutions. Titles and abstracts were examined to determine relevance and if unclear the full article was retrieved and read. The Australian Indigenous Education and Research Health Bibliography Kurongkurl Katitjin (http://www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au/) was also searched for relevant publications. No articles were identified.

Table 3. Search Terms for Peer Reviewed Literature

Note. If not otherwise indicated, search terms were searched as free text.

Grey Literature

Australian grey literature was searched using Google Scholar (see Tables 1 and 3). Searches were restricted to the first 100 results from each of sixteen searches. Only one article, an examination of dominant academic discourses in Australian ART policy, was identified (Reference Doherty6).

Community Response to Media

Community responses to the proposed policy changes were identified in discussion forums appended to—or blogs and public on-line forums which responded to—relevant media articles. Public on-line social networking sites were also searched (see Table 1). It is possible that site owner(s) may have removed offensive postings or in the case of personal sites, any they did not agree with. If there was difficulty ascertaining the writer's nationality or whether the site represented commercial interests, it was excluded.

Data Analysis

Data for analysis included fifty-nine media articles, thirty-nine discussion forums, relevant postings from thirteen blogs and three Facebook pages. Data were imported into NVivo 8 (QSR International) and analyzed thematically in the tradition of grounded theory (Reference Liamputtong and Ezzy17, p. 265). S.H. and J.S. independently carried out initial open coding. These were subsequently discussed and any differences resolved. In open coding, some codes arose from the 2005 attempt to change the criteria for funding and from our framework of health technology assessment, namely the prognostic factors described by the codes, “maternal age” and “number of cycles,” and others emerged from the material itself such as “profiteering” which related to the Government's framing of the proposed policy change as a bulwark against clinic profiteering. After extensive open coding, a more in-depth analysis of the relationships between the codes was performed by J.S. and S.H. with associated division and collapsing of codes and their organization into relationship trees. For example, the codes “2005 policy,” “lobbying,” “Opposition,” and “backflips” were grouped under the code “political resistance” because they all related to rhetoric in the political arena which aimed to undermine the case for policy change. Comparison between the coding for media and coding for community comments also occurred at this stage. This was followed by selective coding where we identified overarching themes and built relationship diagrams. One such overarching theme was “value of a baby” which found resonance both in the media and community responses. Themes expressed by a minority of participants such as religious views about the acceptability of ART or arguments for the desirability of “natural selection” are not included in this paper. A list of quotations supporting the major themes can be found in Supplementary Table 2, which can be viewed online at www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011028.

FINDINGS

The media articles focused on the significance of parenthood and the potential impact of policy change on the ability to achieve parenthood but also gave considerable space to the political context, the nature of the potential policy changes and the opinions of politicians and lobbyists with respect to such changes. Community views, expressed in discussion forums and blogs, reflected a much broader slate of opinion topics. Abortion, adoption, overpopulation, scarce resources, equity, comparison with alternate funding choices, and the expectations and rights of taxpayers were discussed. There was little consensus building amongst forum participants and, although individual comments were often reflective of a broader political stance, for example, neo-liberal or feminist, the discussion ranged well beyond an examination of party politics. In most cases, particular comments within a forum caused a flurry of reactive discussion which would then be temporally replaced by reactive discussion around an alternate issue. In contrast, discussion on blogs or Facebook pages devoted to ART users was cohesive.

The primary themes identified across the sourcesthe va were lue of parenthood, perceptions of profiteering by doctors, accountability for public money and managing public policy choices. There was very little discussion relating to the prognostic factors around which potential disinvestment from ART had been framed in 2005: limits on funding based on maternal age and number of ART cycles. Participants framed the issue in particular ways to support their case: for example, supporters of public funding for ART framed infertility as a medical condition whereas nonsupporters, in contrast, framed it as a lifestyle choice which was non-essential.

Value of Parenthood

A subset of twelve media articles, drawn primarily from tabloid newspapers, focused on the high value placed on parenthood in Australian society. These used emotive photos and language including a widely quoted response from one Federal Senator that restrictions on public funding for ART would be pricing people out of parenthood (Reference Drape8) and from another that it amounted to a tax on mothers (Reference Drape8). Personal stories of experience with ART and/or childbirth formed the basis of 24 articles (e.g., (Reference Chester3)), including one from a Federal Member of Parliament (Reference Morrison19). The most emotive articles described babies as miracles (Reference O'Brien20) and suggested that attempts to place a value on a baby were inappropriate. Others reported the anger of families who saw the cuts as unjust (Reference O'Brien20) and described the torment experienced by families undergoing ART (Reference Morrison19;Reference O'Brien20).

Similarly the community response, particularly in blogs and forums devoted to ART advocacy, focused on the value of parenthood and the strong emotion bound up in the desire for children. Participants used emotive language to describe the revelation of infertility as heartbreaking and the children born of ART as precious miracles who are deeply loved and cherished. Many participants indicated that reducing public funding would price ART services beyond reach. Media discussion forum participants were less sympathetic and painted the desire for children as an irrational desire to breed and parenthood as only one of the options that life might provide. The majority of posts opposed to disinvestment in ART were posted by those who indicated they were present or past users of ART with only one comment in favor of disinvestment from an individual who identified as an ART consumer.

Allegations of Profiteering by Doctors

Broad coverage was given to the Government's primary argument, that burgeoning ART costs ensued from doctors’ profiteering (Reference Ryan22). However, even more space was devoted to strong responses from clinician lobbyists and a patient lobby group including denial that costs were as high as reported (Reference Cresswell4) or alternatively that costs were in line with general medical inflation (Reference Miller18;Reference Robotham21), proceeded from improved costlier methods (Reference Robotham21), constituted “catch-up” for previous inadequate funding (Reference Ryan22), or represented costs of large staff loads (Reference Miller18).

Most responses in discussion forums and blogs were critical of doctors. Patients complained of large price hikes in private ART services and variability in out-of-pocket expenses. Respondents called for redirection of investment away from private clinics and toward the public sector. One respondent questioned the integrity of some ART physicians:

. . .baby making is big business and there are some people out there selling false promises. [“Rev,” Money Mum Blog] (Reference Davies5)

Some ART users considered that the policy changes would target patients and instead should target doctors rorting the system. One respondent summarized these views:

If the unrasonable [sic] increase in specialists [sic] fees are truly to blame for these budget cutbacks, why don't you actually implement one of your election promises–reform medical system. [“Katherine,” Discussion forum: Daily Telegraph] (Reference Dunlevy10)

Managing Public Money and Policy Choices

Many media articles reported the Government line, namely that restricting public funding to ART was responsible budgeting. Some emphasized the issue of burgeoning cost but many also covered the medical lobby backlash (e.g., Reference Gordon13). However, greater media emphasis fell on the financial pressure threatening individual patients than on that faced by National budgets.

In contrast, respondents on discussion forums and those blogs not dedicated to supporting ART public funding, recognized the problems associated with managing a budget for a system where demands are theoretically unlimited. Some respondents questioned the use of funds for ART when rural areas and marginalized groups lacked access to good health care, while others saw it as part of a larger area where disinvestment was needed.

So first taxpayers (and yes taxpayers include people who don't WANT children) have to help subsidize the IVF, then we have to subsidize the baby bonus, and then if it's a working mother the up to 26 weeks paid leave! Give me a break. [“Kelly of Brisbane,” Discussion forum: Courier Mail] (Reference Chester3)

Many, however, questioned why ART funding should be targeted when these other benefits for fertile couples would continue (Reference Haydon14).

Prognostic Factors

We were interested in how relevant prognostic factors that could form the basis for disinvestment, such as maternal age and number of cycles, were discussed. The 2009 change was not focused on prognostic factors thus this aspect attracted little attention in news or social media although the perceived need to fund several cycles to maximize success was discussed (Reference O'Brien20). Any focus on prognostic factors was challenged, particularly on ART support blogs and Facebook pages, on the basis that many couples and individuals accessing ART were of normal weight and young or, if older, had already effectively paid for ART in their taxes.

A Human Right or a Lifestyle Choice

Some supporters of public funding for ART framed the issue as a basic right:

We have every right to have children. We didn't ask to have fertility issues. This is the hand we have been dealt and they should admire our strength and determination to strive for our dream. [“Tanya Spreitzer,” Discussion forum: Sunday Mail] (Reference Doherty7)

The principal patient lobby group gained wide coverage for its opposition to the proposed policy changes by focusing on the issue of equity (Reference Drape8). This stance reflected the sentiment of a Senator: the proposed changes would make IVF affordable only for the wealthy and were inequitable in targeting a common medical condition for funding restriction (Reference Xenophon25). No articles discussed the inequitable exclusion of those unable to afford up-front payments or out-of-pocket expenses. This issue was raised in a small number of community postings which suggested that it was doubly unfair because consumers had to deal with both the pain of infertility and the financial cost of ART.

The framing of the issue as a right was challenged by many respondents who portrayed the use of ART services variously as a lifestyle choice, selfish desire or luxury good.

You have a basic maternity right–the right to get pregnant & be maternal. It doesn't provide a “right” to have us pay for it. Your kid, your cost. [“PGS,” Discussion forum: Daily Telegraph (Reference Dunlevy9)

Some respondents suggested that resources were limited in a context of competing needs but others were more concerned about the impact on society from what they saw as an unnatural experiment. Some forum participants singled out IVF users for vilification, accusing them of not only contributing to their own failure to reproduce but also being selfish.

How about the link between infertility and obesity? Try losing weight, you'll save money on cheesecakes and treatment. [“Brett,” Discussion forum: Sunday Mail] (Reference Doherty7)

IVF is for selfish people. It's not a desire for children per se–more of the biological imperialist attitude of MINE! [“REDstar,” Blog response: The Punch] (Reference Xenophon25)

It is not surprising that many ART consumers chose to only participate in sympathetic forums and that, in response to this unsympathetic framing of the debate, supporters of public funding for IVF positioned themselves as worthy taxpaying citizens “deserving” of funding.

I have paid tax since I was 14yrs and 9mths of age. Why shouldn't I claim on the one thing I have needed assistance for in my life? [“Vicki Clare-Geluk,” Facebook] (Reference Vicki24)

DISCUSSION

Currently, there are few standardized methods for examining the social aspects of a health technology, particularly in the context of disinvestment. A variety of techniques have been used to collect public preferences, including consumer representation, conjoint analysis, surveys, interviews, focus groups, and citizen juries (Reference Braunack-Mayer, Street and Rogers2;Reference Facey, Boivin and Gracia12;Reference Street, Braunack-Mayer, Facey, Ashcroft and Hiller23). Only some engage with and elucidate broader socio-political contexts. We have previously demonstrated that information about social aspects of a new technology may be collected from on-line social media (Reference Street, Braunack-Mayer, Facey, Ashcroft and Hiller23). In our current research, we extend this method to examine the socio-political aspects of disinvestment from an existing technology using an analysis of on-line news media, discussion forums and blogs.

In 2009, with little reference to the broader socio-political landscape, Australian news media narrowly framed proposals for disinvestment from ART public funding as: (i) the emotive narrative of individual infertility distress and (ii) the political nexus of interests. Similar findings were reported in a media analysis examining the introduction of the drug Herceptin (Reference Abelson and Collins1). Canadian and UK coverage of the story used primarily “individualistic general story frames” with positive framing of the benefits of the drug and little consideration of societal impact particularly in terms of differential effectiveness, capacity to benefit, and opportunity cost.

By contrast, in our study, discussion on forums and blogs in response to media articles about disinvestment from ART funding, although incorporating both of these frameworks, was more complex, placing the issue within the context of limited resources and alternative policy funding choices and a variety of broader social issues. Of interest, the argument used by the Government to support disinvestment was not explicitly framed as the usual relative cost-effectiveness argument but rather one of controlling greed (of providers). This shifted responsibility for the cuts away from Government and highlighted the notion of opportunity cost, where less profit need not impact services, but permit redeployment of scarce resources. This resonated with on-line respondents who recognized the impact of commercial interests and questioned the primarily uncritical portrayal of ART providers in the media. Of interest, there is no clear unified message of community support for ART public funding on blogs and discussion forums despite research which suggests that public opinion strongly favors such measures (Reference Kovacs, Morgan, Wood, Forbes and Howlett15). This may be because the majority nonpartisan community voice is not well represented within these forums. In addition, the voices of the consumer majority, those who had undergone ART but not gone home with a baby, were largely silent. The major voices represented in the forums and blogs were polarized: disenchanted taxpayers and defensive IVF consumers.

Web 2.0 sites differ from traditional media commentary, such as letters to the editor or talkback radio, in that posts may be unfiltered and are often anonymous. This permits the collection of views which may be popular in the community but not generally collectable through standard research methods because self-selected participants may moderate their views in interaction with others. A limitation of the research is the lack of participant demographic data and the potential for commercial interference in influencing the debate through fabricated posts and promotion of consumer protest.

A clearer understanding of the socio-political context for disinvestment from ART in Australia emerges from the interaction of media and public. This interaction is itself underpinned by the relationship between politics and scientific evidence. Lehoux and Blume (Reference Lehoux and Blume16) classify three types of such interactions: political shaping of knowledge, social distribution of authority between experts and lay participants and, business steering of knowledge. With respect to the political shaping of knowledge it is apparent that the nature of knowledge collected in a standard HTA is different to that synthesized from news articles and social media. “Evidence” in the form of efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness is relatively unimportant if ART is framed as a right or ART patients as selfish. Similarly, the dominant role of clinician as expert in this disinvestment agenda may be problematic due to conflict of interest. In particular, disinvestment from ART public funding impacts on the livelihoods of ART clinicians and the viability of private ART clinics. Some public participants in the discussion forums recognized this conflict and challenged ART clinicians’ standing as experts in this debate. This connects to the importance of industry steering of knowledge: framing infertility as a medical condition, as ART clinicians did (and beyond this, ART consumers), places funding for ART into the protected realm of doctor–patient decision making.

Our findings suggest that social media stimulates broader discussion of the issues and provides a more diverse range of opinions and concerns than traditional media. We would note that for each participant with an “extreme” view who posted on a social media site, it is probable that there were many with more neutral views who read the site but did not post. Provided the site was not specifically targeted to a particular audience, such as those offering support for women undergoing IVF, the discussion presented on social media was often more wide ranging than that seen in traditional media, albeit more extreme and polarized in its nature.

This research suggests that, in the case of a disinvestment deliberation, where there are strongly held beliefs and values, traditional news, and social media may be dominated by polarized debate. Understanding this debate is essential if we are to understand the social and political aspects of ART and other contentious technologies. In our case study, it is possible that a better understanding of the community response to the 2005 disinvestment attempts would have assisted policy change in 2009. Our study provides a window into the nature and extent of the debate but additional measures of community and stakeholder engagement would be useful if further disinvestment attempts are envisaged.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 3

www.journals.cambridge.org/thc2011028

CONTACT INFORMATION

Jackie M. Street, PhD (jackie.street@adelaide.edu.au), Sophie E. Hennessy, BHlthSc (sophie.hennessy@student.adelaide.edu.au), Amber M. Watt, MPH (amber.watt@adelaide.edu.au), The University of Adelaide–School of Population Health and Clinical Practice Level 7, 178 North Terrace Mail Drop 650 550, Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia

Janet E. Hiller, MPH, PhD (janet.hiller@acu.edu.au), Faculty of Health Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Locked Bag 4115, Fitzroy, MDC, VIC 3065, Australia

Adam G. Elshaug, MPH, PhD (adam.elshaug@adelaide.edu.au), Department of Health Care Policy, Harvard Medical School, 180 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors report they have no potential conflicts of interest.