Over the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Arabic language underwent profound transformations due to communication revolutions like the introduction of the telegraph and the expansion of the press, new translation practices and attitudes towards writing, state-building projects, and educational reforms. In particular, the press was a central domain of original language debates and innovative stylistic and translation practices during this period, with editors and intellectuals of the Nahda (the so-called Arab literary and cultural renaissance) expending extensive effort to theorize and reform language.

However, it was not only the Arabic language that came under renewed scrutiny in this period, but also its alphabet, including the possibility of romanizing it. In 1889, Ottoman Syrian editors Yaʿqub Sarruf (1852–1927) and Faris Nimr (1857–1951) designed a model for writing the Arabic language using the Latin script and showcased it in their Egypt-based, popular-science monthly magazine al-Muqtataf (The Digest, first established in Beirut in 1876). Al-Muqtataf was arguably the most popular Arabic science periodical of its time. It was committed to producing accessible knowledge, seen as key to the cultural and social progress of Egyptians and Arabic-speaking readers at large, and played an important role in popularizing translation practices and conventions.Footnote 1 As was the case for other contemporary magazines, al-Muqtataf was reportedly read “from Fez to Baghdad, from Beirut to Aden, and from Cairo to Bombay, as well as in Europe.”Footnote 2 While low literacy levels hampered the overall spread of publications, for intellectuals, politicians, activists, students, and the growing educated middle class more broadly, newspapers and magazines represented a key arena for political and intellectual debate. Editors, journalists, intellectuals, as well as readers themselves used the press to put forth an array of views and agendas, with publications often seeking financial support from, or aligning with, local political parties and foreign powers. Al-Muqtataf espoused anti-Ottoman and pro-British tendencies, with the daily al-Muqattam, founded in 1889 and published by the same press, engaging in blatantly one-sided news coverage in defense of the British, who had occupied Egypt since 1882.Footnote 3

In 1897, around a decade after publishing their first romanization model, Sarruf and Nimr developed and publicized yet another romanization system, which—while presenting some formal differences in terms of the Latin fonts selected to represent Arabic characters—

still stemmed from the same rationale as the 1889 model. I refer to al-Muqtataf's models as instances of romanization, a capacious term that can be used both as a synonym of transliteration and to refer to the concrete practice through which an alphabet reform is carried out, in order to account for the degree of ambiguity in the editors’ conception and use of Latin-script Arabic. Sarruf and Nimr specified that they were “not among those inciting to replace the Arabic alphabet with a different one.” Still, they sought to present their readers with what they regarded as the best way to do so, “if it were necessary,” and to note its potential benefits.Footnote 4 From this perspective, al-Muqtataf's Latin-script Arabic did not amount to an attempt at alphabet reform. Yet, at the same time, it was also envisioned by the editors as potentially suited for more than just transliteration, the rendering of “single foreign-language words or phrases” in a text written in a different language.Footnote 5 Sarruf and Nimr's models were not designed to write isolated Arabic words or sentences in a text written in a different language, but rather to produce an Arabic-language text using a different script. The models, moreover, could ideally be used in any linguistic domain, including the press, advertising, or––as Sarruf and Nimr showed through a sample excerpt they wrote in the new script in 1897––Arabic poetry from the Abbasid period.Footnote 6

Al-Muqtataf was unique, at least among non-European publications, in designing romanization models in the nineteenth century. Crucially, however, it did so in a context of widespread transformations in transliteration practices and the technological and financial workings of the press. The nineteenth century, and particularly the turn of the century, was a time of unprecedented growth in the press and publishing industry. Several dozen new printing presses were established in Egypt between the 1880s and 1910s, with most large publications also operating in the book market.Footnote 7 Matbaʿat al-Muqtataf (al-Muqtataf Press), for example, printed numerous books in both Arabic and European languages alongside the monthly magazine al-Muqtataf and daily newspaper al-Muqattam. Since at least the mid-nineteenth century, as I show here, orientalist and Arab scholars, government officials, publishers, and advertisers in Egypt and beyond increasingly experimented with, commented on, or sought to regulate transliteration practices, even proposing, in a few instances, outright alphabet reforms.

Moreover, romanization endeavors were by no means limited to Egypt in this period. As Uluğ Kuzuoğlu's 2021 study of the Chinese-language romanization activities of Protestant missionaries in Qing China demonstrates, the nineteenth century was a global moment of romanization attempts that were “as much an extension of Western imperialism as of industrialized print.”Footnote 8 Sarruf and Nimr's discussion of Arabic's romanization, and the development of models to do so, similarly constituted an attempt to pursue financial profit and technological efficiency in the publishing industry. From this perspective, the case of al-Muqtataf contributes to a burgeoning transregional investigation of the role of new media technologies and the workings of the press as an industry in debates about romanization. Yet, in addition to addressing questions of technology and the economy of printing, al-Muqtataf's editors also regarded romanization as a new and original avenue to promote Arabic-language scientific and intellectual production within transregional publishing networks encompassing different languages, chiefly Latin-script, European ones.

The nineteenth century was indeed a time of global reconfiguration of scripts. In addition to the missionary romanization activities in Qing China, in this period we also find “cross-imperial debates” around romanization in the Russian and Ottoman empires, which, starting in the 1860s, laid the bases for the later wave of 1920s alphabet reforms in the Turkish Republic and the USSR.Footnote 9 In nineteenth-century colonial India, various British officials and missionaries promoted romanization through the press and education, elevating the Latin script to “a symbol of modernity itself.”Footnote 10 Starting in the 1870s, moreover, early attempts at alphabet reform stemming from nationalist and independence movements––like the romanization of Albanian proposed by some Ottoman-Albanian intellectuals since the 1870s––were also made.Footnote 11

I thus situate Arabic romanization within a global history of alphabet reform and romanization debates to discern its similarity to and distinctiveness from contemporary and later instances within and beyond Egypt, contributing to “a new history of scripts” predicated on a transnational approach.Footnote 12 In particular, the case of al-Muqtataf allows us, on the one hand, to further situate romanization attempts within the broader context of experimentation with typography and, on the other hand, to disentangle the association of debates over scripts and alphabet reform in the modern period that fall overwhelmingly within a national framework. Unlike, for example, the 1928 Turkish alphabet reform and more notorious proposals to romanize Arabic in Egypt in the mid-twentieth century, such as those advanced by ʿAbd al-ʿAziz Fahmi (1870–1951) and Salama Musa (1887–1958), al-Muqtataf's new Latin script for the Arabic language did not stem from nationalist or state-building concerns, but rather targeted transregional Arabic-speaking publishing networks that included, but were not limited to, Egypt. Therefore, al-Muqtataf's romanization model opens alternative geographies of script that equally partook in this historical moment of global reconfiguration and investigation of alphabets and languages.

Sarruf and Nimr's early discussion of the possibility of employing the Latin script to write the Arabic language, and the models they designed, have, to my knowledge, never been previously discussed. More generally, debates from this period about Arabic's romanization have received very little scholarly attention, with the few works on the topic focusing largely on the activities of foreign scholars, such as Liesbeth Zack's illuminating study of the work of American linguist Daniel Willard Fiske (1831–1904), who developed a Latin-script version of colloquial Egyptian Arabic in the 1890s, which I return to later in the article.Footnote 13 Therefore, even though some romanization debates in the Egyptian press did emerge in dialogue with the activities of foreign intellectuals and orientalists, I focus first and foremost on the local and regional factors that shaped discussions of romanization in the Egyptian press since the late nineteenth century.Footnote 14

After introducing al-Muqtataf's models and situating them within the wider context of romanization attempts and debates in the domains of orientalist knowledge production, “mundane” transliteration practices in the press and beyond, and governance, this article examines, first, the technical and financial motivations and, second, the intellectual and ideological concerns that informed al-Muqtataf's romanization endeavors. No publisher––including, crucially, al-Muqtataf's own––began using the magazine's new script for Arabic. Still, scripts are historical artifacts rather than neutral tools informed simply by convention or practicality. Examining instances in which they are called into question, even if isolated, thus offers a unique opportunity to identify otherwise overlooked intellectual concerns and political stakes.

Governing Scripts and Through Scripts

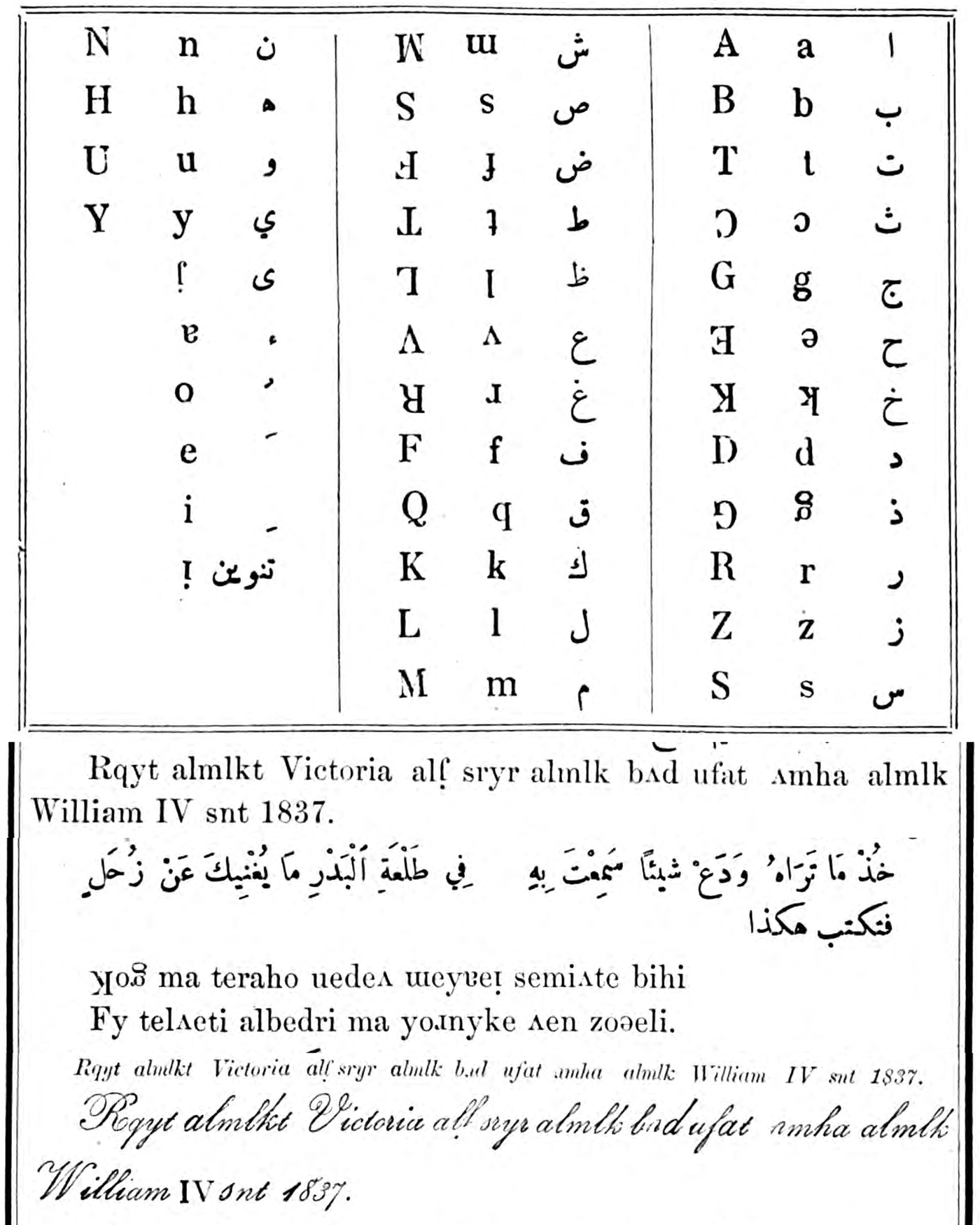

Al-Muqtataf's 1889 and 1897 romanization models were predicated on the same rationale and served two key goals.Footnote 15 On the one hand, they aimed to reduce the expenses of publishers and editors, making them more competitive vis-à-vis those printing in European languages. Sarruf and Nimr achieved this by designing a system that romanized Arabic using only the fonts already found in Latin-script printing presses (Fig. 1). This way, publishers did not have to purchase or mold new typefaces featuring “dots and lines,” meaning diacritics (as those commonly used in transliteration methods at the time, which I return to in the next section).

Figure 1. Alphabet chart and sample sentences in “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi” (Latin Letters for the Arabic Script), al-Muqtataf, September 1, 1897, 689–90.

On the other hand, the editors of al-Muqtataf saw romanization as conducive to the spread of knowledge and information among Arabic-speaking readers, particularly with regard to foreign terms. In fact, romanization was seen as solving the “problem,” as the editors referred to it, of translating or conveying European words (naqala), as writing Arabic in Latin script allowed one to, for example, leave “European names in their original spelling” (al-aʿlām al-ifranjiyya bi-tahji'tihā al-aṣliyya).Footnote 16 While this issue was discussed only with reference to proper names (aʿlām) in al-Muqtataf's articles on romanization, it fed into the magazine's views on translation more broadly; chiefly, its positive attitude towards the incorporation of foreign words into Arabic.Footnote 17 As Marwa Elshakry noted, the editors regarded European scientific and intellectual production as a primary reference point, rooted in a long-held belief that there was “no shame in borrowing from the West.”Footnote 18 This attitude informed not only the magazine's stance on translation and the dissemination of knowledge, but also, as we see in detail in the third section of the article, its discussion of Arabic's romanization.

Sarruf and Nimr's proposed models for writing Arabic in Latin script were a direct response to some of the transliteration methods developed by orientalists as well as linguists and journalists from the Middle East in the late nineteenth century. Contemporary publications employed various methods to transliterate or transcribe (the rendition of speech in writing) Arabic words and text excerpts for Western consumption. Tourist books, for example, privileged transcription over transliteration, and Egyptian Arabic over fuṣḥā (Classical Arabic), due to their focus on rendering simple oral interactions. Orientalist grammars, readers, and scholarly publications, meanwhile, appear to have used a variety of transliteration systems, as shown by repeated attempts to standardize the transliteration of non-Latin script languages, such as Arabic. In 1895, for example, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, a leading British orientalist publication, published the report of the “Committee appointed by the Congress,” meaning that year's International Congress of Orientalists, “to select a system for the transliteration of the Sanskrit and Arabic Alphabets.” The committee had reviewed the work of another special committee appointed by The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society itself, as well as the “systems of transliteration usually adopted in France [and] in Germany,” in order to develop a system “with a view to general adoption by Orientalists.” It was hoped that “Orientalists in every country will endeavour to still further reduce [the number of alternative methods] by conforming as much as possible to the system recommended by the Committee.”Footnote 19 Crucially, the transliteration model designed by the committee made use of diacritics—precisely what the editors of al-Muqtataf had sought to avoid when developing their romanization methods (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. “Transliteration of Arabic Alphabet,” The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 27, no. 4 (1895): 882.

In the same period, some orientalist scholars even designed and attempted to promote outright alphabet reforms for local, “vernacular” languages. In the 1890s, as Zack details, Fiske developed a Latin-script version of colloquial Egyptian Arabic that, he believed, should become Egypt's national language.Footnote 20 A similar stance informed the call by Selden Willmore (1856–1931)––a British scholar who held official positions across Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, including as a judge in the Cairo Native Court of Appeal––in his 1901 book The Spoken Arabic of Egypt, to use Egyptian Arabic and the Roman alphabet.Footnote 21 However, it was not only European and North American scholars who sought to standardize transliteration, or even push for full-on romanization. Indeed, in 1889, al-Muqtataf published an article by the Damascene scholar Ilyas al-Qudsi (1850–1926) that presented a transliteration method for writing Arabic words and names using the Latin script. Al-Qudsi's transliteration method once again included diacritics, which al-Muqtataf's editors categorically sought to avoid.Footnote 22

Publishers and journalists in Egypt, including but not limited to al-Muqtataf, were quick to engage with the question of Arabic romanization. Zack, for example, rightly suggests that the criticism of a “project of some foreigners” to romanize Egyptian Arabic expressed in 1898 in the review section of the literary and scientific magazine al-Hilal (The Crescent, established in 1892) was most likely a response to Fiske's work.Footnote 23 Al-Muqtaṭaf's 1889 and 1897 articles, in turn, were direct responses to the transliteration method developed by al-Qudsi and the alphabet reform proposed by Fiske respectively, and offered models for writing Arabic in the Latin script that the editors regarded as more efficient and profitable for printers of the Arabic language.

Additionally, due to the presence of “spontaneous” instances of romanization in newspaper and magazine headers, shop signs, and advertisements, Egypt's visual environments displayed a variety of scripts that did not necessarily conform to any given standardized model. Arabic words and expressions, including proper names and technical terms, had long been rendered in Latin script. Further, there existed several different, nonsystematic renditions of Arabic words that employed the Latin script without resorting to diacritics (as in scholarly transliterations) or to a full-fledged romanization model (like the one designed by al-Muqtataf). Instances of this kind of romanized Arabic appeared in manuscripts and later in printed materials such as newspapers and magazines, stamps, language textbooks, maps, legal documents, and official certificates. Many Arabic newspapers and magazines printed in Egypt from at least the third quarter of the nineteenth century, for example, featured Arabic words in Latin script, especially in their headers (Fig. 3), possibly to make their titles legible to non-Arabic speaking readers, and in advertisements for foreign businesses or local ones seeking to entice customers by stressing the “European” character of their products.

Figure 3. Examples of newspaper and magazine headers from the turn of the century featuring Latin-script Arabic. Al-Muqtataf XVI, 1892; and al-Ahram, December 10, 1902.

Such “extemporaneous” romanization practices were not only confined to the press, however, as they also characterized more mundane domains, engaging audiences with different degrees of literacy and foreign language skills, as in the case of street and shop signs, train tickets, and coins.Footnote 24 Photographs from the turn of the century show that many shop signs and display material designed for public consumption incorporated Arabic written in Latin script, as well as European words written in the Arabic alphabet, particularly in commercial streets in cities and areas where the highest concentration of Europeans lived, such as Cairo, Alexandria, and the Suez Canal cities. The exposure to and consumption of multiple languages and alphabets was thus not limited to educated elites trained in foreign languages, but was also part of the daily experience of individuals from various social classes and backgrounds as they navigated their city, used coins, or took the train.

The presence of different “mundane,” unregulated transliteration practices was criticized in the press and by state authorities for its allegedly unregulated character and potential for generating confusion. In 1915, al-Hilal published the article “Arabic Writing with Foreign Letters,” which reported the opinion of William Worrell (1879–1952), the “well known American orientalist,” on the confusing way Arabic words were written in the Roman alphabet in Egypt at the time. Worrell's complaint specifically concerned street signs. The Arabic word shāriʿ (street), he noted, was written as “chareh,” which caused different pronunciations by English, French, and Italian speakers, who read this as “chary,” “shary,” or “kary” respectively. The article went on to remind readers that “orientalists have set clear rules […] to govern the [Arabic] letters and short vowels (harakāt).” To remind the reader of the “correct” way of romanizing Arabic, al-Hilal featured a chart displaying a common transliteration method that employed diacritical marks, not dissimilar to the one featured in 1895 in The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society.

The perceived confusion brought on by the multiplicity of ways in which foreign words were written in Arabic was a concern for not only journalists and intellectuals, but for state and colonial officials as well. As Yasir Suleiman notes in A War of Words, orientalists’ interest in linguistic matters went hand in hand with “extralinguistic concerns,” primarily the furthering of imperial objectives. This was the case, for instance, with geographic knowledge and the issue of toponyms in maps. In his 1895 Handbook of Modern Arabic, Oxford fellow Francis Newman (1805–97) characterized the “intervention of the European character [alphabet] and European maps” as key to promoting the “intelligence and prosperity of Turkey, and with it all the solid and legitimate interests of England.”Footnote 25

With respect to Egypt specifically, since the beginning of the de facto occupation in 1882, which saw British “advisors” routinely appointed to oversee government ministries, correspondence and official publications were often written in multiple languages, mainly Arabic and French, but also English. To my knowledge, at least two separate attempts were made to standardize romanization practices in the domain of governance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before the emergence of more ambitious, if still relatively isolated, attempts following the establishment of the Egyptian Language Academy in 1936. In 1915, the British established a commission to revise and standardize the transliteration of Arabic terms in English. Similar to Newman, the commission was concerned with “maps” and “reports dealing with topographical matter, desert expeditions, engineering and similar subjects,” which, in the absence of a consistent system of transliteration, “will decrease in value and may sometimes be actually misleading.” Once again, differences in the transliteration of Arabic terms were attributed to the fact that “a Frenchman would write a name down in one way, an Englishman in another, and Italian or German according to his own mother tongue and so on,” as well as to the poor Arabic proficiency of the officers responsible for compiling maps.Footnote 26

Yet it was not only colonial authorities raising the alarm regarding inconsistent romanization practices in Egypt's administration. Already in 1892, Egyptian Minister of Education Muhammad Zaki Pasha proposed that a commission be formed to standardize how Arabic words were written in English and French, and vice versa, due to “the mistakes made especially in official correspondence between governmental bodies.”Footnote 27 To demonstrate the gravity of the situation, Zaki attached a list of words taken from recent issues of the official government bulletin, the then Arabic-French bilingual al-Waqaʾiʿ al-Misriyya/Journal Officiel, showcasing the many different spellings of Arabic words rendered in English and French, as well as French words in Arabic (Fig. 4). The French title “Capitaine,” for example, was rendered in Arabic as either “qabudān” or “qabṭān,” and the word “poste” (mail) as “al-busta” or “al-busṭa.”

Figure 4. “Examples of Transcription from French to Arabic,” Majlis al-Nuzzar wa-l-Wuzara' (December 24, 1892), DWQ #0075-044061.

Adopting a consistent transliteration system was not only crucial “from a linguistic point of view,” Zaki pointed out, but was also needed to avert “serious administrative and legal inconveniences due to the mistakes that might arise from the different transcription of proper names, the names of localities, technical or scientific terms, etc.” The governing of scripts through the standardization of transliteration was thus not only an imperial impulse, but also a governmental concern for local state officials navigating a multi-script bureaucratic environment.

Arabic Romanization as a Typographic Endeavor

Therefore, when al-Muqtataf designed its romanization models, it did so in an environment of scripts already crowded with unregulated, “spontaneous” instances of romanized Arabic, as well as more or less established, learned transliteration practices. The editors of al-Muqtataf took issue not only with the alleged “chaos” of multiple transliteration methods, but also with their inefficiency from an economic perspective. The most explicit argument made by al-Muqtataf's editors for the need to romanize Arabic was, in fact, financial. The 1897 “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi” (Latin Letters for the Arabic Script), as the longer al-Muqtataf article on romanization (and hence the one most relied on in this discussion) was titled, opened by noting: “as soon as printing started spreading in our region [Egypt] and the Levant, Arabs and Europeans who study our language felt the strong necessity of reforming the letters of printed Arabic.”Footnote 28 Molding Arabic typographic fonts, it was argued, posed technical difficulties and high production costs, rendering the reform of printed Arabic a priority. Before presenting their romanization model, Sarruf and Nimr reviewed alternative ways of resolving this problem. One option they discussed drew on contemporary transliteration methods, such as those previously examined, and entailed writing Arabic in Latin script by adding diacritics to Latin typefaces in order to accommodate for Arabic letters with no direct equivalent in European languages.

However, the editors soon dismissed this method as unproductive. Publishers of romanized Arabic, they argued, needed to avoid having to procure new typographical fonts as a way of limiting production expenses. While buying printing equipment does not appear to have been prohibitively expensive, it remained one of the largest expenses for publishers, along with postage for newspapers and magazines. Kathryn Schwartz notes that “[a]lmost all of the major Egyptian-owned presses of the 1860s and 1870s employed typefaces that once belonged to the government.”Footnote 29 In later decades as well, “[m]ost presses utilized primitive equipment and methods, as labor costs for setting type and folding the paper manually were so low that it did not pay to install more advanced and costlier machines.”Footnote 30 This limited evidence might help explain al-Muqtataf's objection to making printers procure new typefaces, especially the less widespread kind featuring Latin typefaces with diacritics. The editors added that Matbaʿat al-Muqtataf had been forced to “sustain enormous expenses in vain” when printing the Arabic language using Latin script––in, for example, books that included foreign terminology or didactical texts––due to the many different romanization models that existed, including those using diacritics.Footnote 31

Sarruf and Nimr's insistence on the economic dimension of the press and publishing industry constituted a dimension of the concern regarding economization, rationalization, and efficiency shared by many contemporary scholars, publishers, and editors. Scholar of literature Hannah Scott Deuchar, for example, has demonstrated that some of the most prominent intellectuals and editors operating in Egypt in the first decade of the twentieth century, including those of al-Muqtataf, theorized literature and language through the economic “notions of equivalency and exchange” embedded in “(imperial) capitalist logics of market efficiency and infinite exchangeability.”Footnote 32 Historians of the Nahda and the Arabic press such as, most recently, Kathryn Schwartz and Leor Halevi, have shown how the political economy of printing and the financial workings of printing presses and journals profoundly affected the editorial choices of publishers and newspaper and magazine owners.Footnote 33

As opposed to the (more costly) option of molding new Latin typefaces with diacritics, al-Muqtataf's romanization model allowed printers to use “the Latin letters that already exist in French, English, and Italian printing, without adding different ones.”Footnote 34 In fact, various local printing presses already had the capacity to print Latin-script foreign languages in addition to Arabic (for example the al-Ahram and al-Hilal printing presses), meaning that adopting al-Muqtataf's romanization models would have ideally been cost-free. In the 1889 article, the editors suggested adding commas and other punctuation signs (all of which were already found in Latin-script printing presses) to some Roman letters in order to write Arabic letters with no direct equivalent in Latin script. For example, if the Arabic letter dāl was rendered as the Latin letter “d,” the letter ḍād, whose sound and respective grapheme are not found in Latin script, was written as the letter “d” with an upside-down semicolon next to it.

The 1897 article, in turn, proposed using letters of the Latin script in upside-down and mirrored positions. For example, if the Arabic letter rāʾ was rendered as “r,” the letter ghayn (which, like the letter ḍād, is not found in Latin script) appeared as an upside-down “r.” In addition to displaying the new script, the editors also included some sample phrases, such as “Queen Victoria ascended to the throne after the death of her uncle king William IV in the year 1837” (Fig. 1). The editors selected this specific sentence to showcase how their new script allowed them to maintain the original spelling of foreign words (such as the proper name “Victoria”), thus avoiding translation and transcription issues, and employ the numbers used in Europe, rather than the Indian ones Arabic traditionally employs. To demonstrate their script's suitability for all genres of Arabic writing and literature, not merely the domain of journalism, the article also included an excerpt from an Abbasid-era poem written in the new alphabet.

Following the first rendition of the sentences, the editors featured additional versions in different styles and fonts, such as italics, in order to display the aesthetic potential of their romanized Arabic. The emphasis on providing multiple and embellished fonts was in keeping with the editors’ growing interest in employing new and graphically-elaborate styles and, particularly, in making them available to advertisers. Advertising, which was entering a new phase in Egypt in the 1890s in terms of variety and quantity of announcements, constituted one of the first and most important domains of experimentation with different designs, discursive strategies, and embellished fonts in both Arabic and Latin scripts. The literary and scientific magazine al-Hilal, a publication at the forefront of new advertising practices, displayed a selection of different fonts in both Roman and Arabic scripts in order to entice advertisers (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. “Ashkal al-Huruf al-‘Arabiyya wa-l-Ifranjiyya fi Matba‘at al-Ta'lif al-Hilal” (Shapes of the Arabic and Latin Letters in the al-Hilal Press), al-Hilal, March 1, 1897, 520.

Offering both Arabic and Latin-script fonts was part of al-Hilal editor Jurji Zaydan's broader strategy to promote advertising in his magazine. Zaydan stressed the importance of alluring readers, prompting advertisers to, for example, “put the name [of the product] and a drawing that attracts the attention.”Footnote 35 The way Zaydan displayed Arabic and Latin typefaces in al-Hilal further reveals an attempt to draw a perfect equivalence between the two scripts in terms of stylistic variety and aesthetic potential. Traditional Arabic calligraphic styles such as “al-thuluth,” as well as novel ones like “al-Amīrikānī” (the American), were in fact juxtaposed to Latin-script styles like “italic,” “bold,” “upper case,” and “lower case.”Footnote 36 By forging a direct parallel between otherwise unrelated features (note, for example, how the chart, despite the fact that the Arabic script does not differentiate between upper and lower cases, still paired upper and lower case styles in Latin script with other alternatives in Arabic), Zaydan sought to present the two alphabets as equally suited to represent different styles, with roughly the same number of options available in the Arabic and Latin scripts (six and seven respectively).

Sarruf and Nimr also commented on the question of advertising, drawing a direct line between the aesthetic quality of fonts and the region's potential for economic growth through the effective promotion of local products and industries. “The small number of Arabic fonts,” they complained, “is inadequate for marketing commercial and industrial goods that need to be advertised with different fonts that attract the attention [of readers],” especially when compared to the “seventy types of capital and small letters [used by] the British and the French.”Footnote 37 From a technological and economic standpoint, al-Muqtataf regarded romanized Arabic as offering an economic advantage to those printing in Arabic, making them more competitive in the international, multilingual printing market, including advertising. As al-Muqtataf's model was the only one using fonts already readily available in many Egyptian printing presses, it was “the most convenient and profitable.”Footnote 38

Arabic Romanization as an Intellectual and Scientific Advantage

Romanizing Arabic, however, had not only technological and financial significance, but also deeply political and cultural implications related to anxieties around the role of Arabic and the Arab world in the context of colonization and confrontation with European knowledge production. A second issue raised by the editors was that of the translatability or, to be more precise, the transcriptability of intellectual and scientific knowledge originating from and traveling across regions using different languages and alphabets. Writing the Arabic language in Latin script would, according to the editors of al-Muqtataf, solve what they perceived as an underlying problem of the local Arabic press: how could writers of Arabic render European words in an efficient and consistent way?

To appreciate al-Muqtataf's conception of romanization as a solution to the unregulated and confusing way in which foreign words were rendered in Arabic, I return to the introduction of “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi.” This presented a further, if ultimately dismissed, strategy to cut typographical costs: reducing the number of Arabic typefaces used to print each letter of the alphabet. In Arabic, letters have a different shape depending both on their position in the word and which letter precedes or follows them. Instead of using different typefaces for these different shapes, the article noted, printers could continue using the Arabic script by employing “one single letter [shape] regardless of whether it is at the beginning, the middle, or the end of the word.”Footnote 39 In this way, they could reduce the number of typefaces needed for printing in Arabic script and, in turn, reduce typographical expenses.

However, this system did nothing to solve what al-Muqtataf regarded as the “problem” of integrating European words into Arabic, an issue that related to the broader question of translation, a key area of debate among Nahda intellectuals. Al-Muqtataf, Elshakry notes, was a primary vehicle and experimental arena for different translation practices and, in virtue of its popularity and commitment to producing accessible knowledge, successfully established some conventions of Arabic scientific terminology still used today. As illustrated by Elshakry, translators used three main strategies to construct neologisms at the time: “Arabicization” (taʿrīb), such as translating the word “democracy” as “al-dīmuqrāṭiyya,” “bank” as “al-bank,” or “bureaucracy” as “al-bīrūqrāṭiyya”; the derivation of words (ishtiqāq) by, for example, turning to older vocabulary to express a new concept; and, finally, the formation of new compound words (naḥt).Footnote 40

Romanization represented yet another way of incorporating foreign words into Arabic, one that bypassed issues of translation and transliteration altogether. Foreign words, al-Muqtataf's editors complained in “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi,” were often rendered in Arabic in multiple, non-standardized versions, creating great confusion. To underscore their point, the editors displayed the numerous ways the word “Gravy” could be written in Arabic.Footnote 41 If rendered in Arabic as ghrāfī, they explained, the word could be read as either “grafi,” “grafy,” “graphy,” or “graphi.” If written as jrāfī (taking advantage of the fact that the Arabic letter “j” is read in Egyptian Arabic as the English hard “g” sound), non-Egyptian Arabic speakers, such as those in the Levant, would mistake the “g” sound for the French soft “j” sound, reading the word as “jravy” instead of “gravy.” By continuing to use this confusing method, the authors declared, local publishers were giving Europeans “an advantage over us.” Instead, if publishers turned to romanization, the whole of the Arabic language would be written using the Latin script and they would be able to “leave the foreign names in their original spelling in order not to lose their origin or corrupt their pronunciation.”Footnote 42

As noted, the romanization of Arabic as conceived by al-Muqtataf remained distinct from the practice of transliteration, which renders “single foreign-language words or phrases [that maintain their] identity as a fragment of another language” within a text fully grounded in its original language.Footnote 43 Al-Qudsi's development of a transliteration system for Arabic in the late nineteenth century, for example, was not at odds with his opposition to romanizing the Arabic language in toto, as he made clear in 1923 when tasked by the Arabic Language Academy of Damascus (established in 1918) with refuting proposals for such a reform.Footnote 44 Instead, what al-Muqtataf envisioned through its romanized Arabic was the complete integration of foreign words into Arabic. Once what the editors regarded as the “problem” of using a different script was removed, words could seamlessly move across languages (or at least those using the Latin script) rather than needing alteration as they moved from one tongue to the other.Footnote 45 Crucially, al-Muqtataf sought to render foreign words in Arabic in the least laborious way possible not only when discussing romanization, but also by resorting to Arabicization often as a translation method; a move criticized by some readers and scholars as corrupting Arabic by overtly importing from European languages.Footnote 46 Thus, the logics of efficiency underlying al-Muqtataf ‘s romanization model manifested when it came to technical and economicas well as intellectual concerns by reducing both printing expenses and the labor of translation.

Skeptical Readers, Defensive Editors

In line with its editorial mission to popularize scientific knowledge, al-Muqtataf hoped to foster debate around the topics it discussed. On November 1, 1897, two months after the publication of “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi,” the magazine featured a reader's critical response in its “Views and Correspondence” section. “To the editors of al-Muqtataf,” wrote reader Salim Shakir, “I read what you wrote about the use of Latin letters instead of Arabic letters and the advantages for Arab printers to only need to use the French, English, or Italian typefaces (literally: al-ḥurūf, letters).” Referring to the practice of adding diacritics to Latin letters to provide for Arabic letters that did not exist in Latin script, Shakir noted: “the readers, whether they are Arabs or not, would read better the [Latin] letter ‘k’ as the [Arabic letter] khāʾ if it had a dot underneath, rather than if it was flipped upside-down,” as al-Muqtataf proposed. Shakir's rejection of the features of al-Muqtataf's romanization model revolved around the issue of legibility and, implicitly, habitus. “A letter upside-down,” he continued, “bothers the eye, and the reader would think there has been an unintentional mistake.”

The editors’ response was quite defensive: “If you were someone who crafts letters, you would know that [adding dots to letters] is harder than it seems.” On the issue of legibility, the editors noted that “some of the Latin letters resemble each other upside-down, like the letters ‘u’ and ‘n’ and ‘d’ and ‘p,’ and yet the eye does not suffer when it reads them because they have been made that way.” “When a man reads,” they added, “he does not pay attention to the form of the letter or its position, but to the word in its entirety.” From their privileged position, the editors further defended their method, and the following month published a second, shorter article on the same topic. It started with the declaration: “many distinguished intellectuals approve of the method of writing Arabic in Latin letters as we have explained.” For the most part, this second article repeated the arguments already introduced in the previous one, but also elaborated on the authors’ reasoning for opting for specific fonts and their orientation. In selecting specific letters, they explained, the editors first rationale was phonetic similarity to Arabic letters, like the use of the Latin letter “s” for the Arabic letter sīn. Their second rationale, however, was purely graphic. The choice of using an upside-down “m” to indicate the Arabic letter shīn, for example, was reportedly down to the similarity in shape of an upside-down “m,” with its two shoulders, to that of the Arabic letter shin, with its two curved lines (Fig. 1).Footnote 47

The exchange between the editors and reader, if read alongside the alleged opinions of the “many distinguished intellectuals [who] approved of the method,” suggests a degree of debate––even if limited to the pages of al-Muqtataf––around the question of romanized Arabic and, specifically, the magazine's model for accomplishing this. Crucially, the reader raised reasonable points; points as revealing for our historical analysis as those advanced by al-Muqtataf itself. The magazine's proposed romanized Arabic, if not “bothering to the eye,” could surely strike one as artificial and disorienting, at least at first. In turn, the editors’ statement, “the eye does not suffer when it reads [the letters] because they have been made that way,” stemmed from the conviction that any script is artificial and based on convention. This point was necessary to the editors’ envisioning of the possibility of romanizing Arabic in the first place, and justified their prioritization of financial and technological concerns over linguistic convention.

At the same time, the editors failed to take on the reader's point about familiarity, as well as the larger context and longer history of Arabic romanization in which they were operating. As noted, al-Muqtataf's romanization model operated in an environment of scripts already replete with unregulated, “spontaneous” instances of romanized Arabic and more or less established transliteration practices, a fact that helps explain the reader's discomfort in the moment of encounter with the magazine's proposed new alphabet. Some twenty years later, the promoters of the Turkish alphabet reform would face a similar challenge. Istanbul newspapers, much like those in Egypt, had been featuring instances of romanization for decades before the 1928 alphabet reform was implemented, particularly in their advertising sections. However, when newspapers began promoting and using the new Turkish alphabet, readership dropped sharply, and most publications managed to weather this transition only through the support of government subsidies.Footnote 48

Printers, writers, intellectuals, and readers envisioned discussions of and experimentation with translation, transcriptability, and cross-linguistic exchange as concerning not only the Arabic-speaking audience, but also European interlocutors. This dual public was a recurrent feature of al-Muqtataf's articles. In addition to its opening statement, which mentioned both “Arabs and Europeans who study our language,” the article “al-Huruf al-Ifranjiyya li-l-Khat al-‘Arabi” repeatedly brought up the theme of the economic and cultural advantage of “them,” Europeans, over “us,” Arabic speakers in Egypt and al-Sham (Greater Syria). The omnipresent backdrop of “European printers,” in fact, emerged not only in relation to the technological aspect of typeface production, but also with respect to the question of readership. The editors of al-Muqtataf regarded romanization as a process that not only modified the script used for Arabic, but also the language itself, particularly as a way to avoid translating and transliterating foreign words, instead allowing for their integration into Arabic without alteration. As foreign languages were understood, at least by the editors of al-Muqtataf, as an inevitable point of reference and competitor Arab intellectuals had to confront economically and intellectually, romanization could represent a new, original strategy aimed at not “giving them [Europeans] an advantage over us, while we will have an advantage over them.”Footnote 49 The new alphabet, in addition to benefitting local publishers and businesses, was in fact seen as expanding the readership of Arabic texts by making them more accessible, thus championing the standing of Arabic and Arab intellectual production within the international, multilingual publishing scene.

At a time when the question of the translation of scientific and literary terms was at the forefront of intellectual debates (first and foremost, in al-Muqtataf itself), even bearing weight on the workings of governance and bureaucracy, the magazine's preference for romanization over translation––at least in the context of the 1889 and 1897 articles discussed here––carried its own political stand and intellectual agenda. Al-Muqtataf's alphabet was the “most convenient and profitable” not only from a financial and technological standpoint, as it reduced the costs and labor needed to print and publish, but also from an intellectual point of view, as it eliminated the labor of conveying words across languages altogether. The editors’ approach to scripts was thus predicated on an association of efficiency with advantage in the production and dissemination of information, which manifested in their deep concern with economic profitability and the rhetoric of competition with European printers.Footnote 50

As previously examined, the discussions and proposed reforms originating in both the press and governmental contexts similarly aimed to affect how scripts were used beyond the domains of intellectual debate and administrative practice. Minister of Education Muhammad Zaki's wish that a standardized transcription system be “imposed on the state administrations as well as the schools of the government,” for example, was tied to the hope that this would “lead the public to adopt it.”Footnote 51 In turn, among the responses to al-Muqtataf's romanization model, some reportedly expressed their desire for the new alphabet to become “widespread and generalized,” and that “Arabic speakers start writing their names using it.”Footnote 52 The domains of intellectual production and governance were thus deeply interconnected as the pursuit of seamless translatability, and transcriptability, across Arabic and the languages of Europe was sustained and reinforced by the reality of foreign encroachment and the Latin script's perceived irrevocable dominance in global printing networks.

Conclusion

Following al-Muqtataf's discussion of romanization in the late nineteenth century, the Egyptian press does not appear to have addressed the question of writing the Arabic language in Latin script extensively until the late 1920s, when the 1928 Turkish alphabet reform stirred new debates around the potential benefits and risks of accomplishing a similar endeavor in Egypt and discussions of the romanization of Arabic became more widespread.Footnote 53 Over the span of around two decades, starting in 1928, al-Ahram featured at least a few dozen articles on the question of romanization. These were generally skeptical, as romanization was seen as entailing “insurmountable difficulties” and unsuited to the “necessities of a language that [the Latin alphabet] has no resemblance to.”Footnote 54 In 1944, ʿAbd al-ʿAziz Fahmi published a book entitled al-Huruf al-Latiniyya li-l-Kitaba al-ʿArabiyya (Latin Letters for Writing in Arabic), which discussed a romanization proposal he had brought before the Egyptian Language Academy.Footnote 55 Citing the example of the Turkish alphabet reform, Fahmi argued that, over the course of two or three months, students would learn the new alphabet perfectly and find it easier to learn foreign languages.Footnote 56 In his 1945 book al-Balagha al-ʿAsriyya wa-l-Lugha al-ʿArabiyya (Eloquence and the Arabic Language), the prominent intellectual Salama Musa also advocated for romanization.Footnote 57 Yet their concerns, different from the earlier debates examined in this article, sought to contribute to the state-led reforms under way at the time. Fahmi's understanding of romanization as part of state-led educational projects was evident, for example, in his insistence on drawing parallels with alphabet reform in Turkey.Footnote 58

Instead, the romanization models proposed in al-Muqtataf primarily targeted the Arabic-speaking publishing and reading circles of the transregional Nahda, chiefly across Egypt and Greater Syria, seeking to carve out a more central place for Arabic within transnational intellectual production and competition. Moreover, the technical features of the magazine's proposed romanization and its insistence on technological and linguistic efficiency were characteristic of the business-oriented attitude of many Nahda-era editors. Al-Muqtataf's emphasis on the aesthetic potential of fonts was a typical example of experimentations with new visual strategies in rapidly developing media like advertising, further demonstrating how––as was the case in other contexts, including Ottoman and Russian inter-imperial printing networks and colonial North India during the same period––the history of romanization was deeply interconnected with developments in and experimentation with typographical printing.

Sustained attempts to romanize Arabic, in Egypt and other Arabic-speaking countries, remained rare throughout the rest of the twentieth century. An interesting exception was the Lebanese nationalist poet and writer Saʿid ʿAql (1911–2014), who designed a romanized version of Lebanese Arabic in the 1970s to promote it as a language independent of standard Arabic. Today, in keeping with the growing “hegemony of the Roman script as the global, universal medium of communication systems,” the Roman script is increasingly employed by smartphone and computer users to write many non-Latin script languages, such as the pinyin transliteration system (originally developed in the 1950s based on earlier romanization models) for Mandarin, and so-called Arabizi or Franco-Arabic, the practice by which Arabic speakers, if only a small minority, write Arabic words using the Latin keyboards of smartphones and computers.Footnote 59

In a 1955 article featured in the Middle Eastern Affairs journal entitled “Arabic Language Problems,” Salama Musa declared: “the time will come when we will go the way the Turks went.”Footnote 60 While his prediction does not seem any likelier to come true today than it was half a century ago, it will be for future historians to assess the trajectory and impact, if limited, of recent romanization practices. What an examination of past instances of romanization, successful or extemporaneous, offers is a reminder to pay attention to the miniscule space of scripts and the historical horizons it can reveal.

Acknowledgements

This article benefitted from the guidance and support of many mentors and colleagues. I am grateful to Zachary Lockman, Sara Pursley, and the three IJMES reviewers. Thanks to Joseph Viscomi, Larry Wolff, Brinkley Messick, Mahnaz Yousefzadeh, and Hasia Diner for providing feedback on this research long before I imagined turning it into an article. I am also indebted to Zack Cuyler, Idriss Jebari, Marianna Pecoraro, Hannah Scott Deuchar, and Gabriel Young for their continued support and help with various drafts, and to the IJMES editor Joel Gordon and associate editor Sarwar Alam for bringing this article to press.