Antibiotic resistance is a major public health burden driven by the unnecessary use of antibiotics. Reference Thompson, Williams and Pulcini1 Dentists contribute significantly to global antibiotic use and are responsible for an estimated 10% of all antibiotics prescribed to humans. The FDI World Dental Federation has highlighted the overwhelming case for restricting the use of antibiotics to only when absolutely necessary. Reference Thompson, Williams and Pulcini1

High rates of dental overprescribing in relation to national guidelines have been identified in Australia, Reference Teoh, Marino and Stewart2 England, Reference Cope, Francis and Wood3 and the United States. Reference Suda, Calip and Zhou4 Comparing appropriateness between countries is difficult, however, because guidelines for therapeutic and prophylactic uses of antibiotics by dentists differ markedly around the world. Reference Thompson, Williams and Pulcini1 Unexplained differences in patterns of antibiotic use have been employed as a means of assessing unnecessary use of antibiotics; England’s UK 5-year national action plan identifies priority actions to reduce variation in antibiotic prescribing between healthcare organizations. 5

Studies of antibiotic prescribing patterns by general dentists in individual countries have been widely undertaken. In North America, an increasing trend has been identified in British Columbia, Canada, Reference Marra, George and Chong6 and in the United States. Reference King, Bartoces and Fleming-Dutra7 By contrast, Australia Reference Teoh, Stewart and Marino8 and England Reference Thornhill, Dayer and Durkin9 have experienced a reducing trend. In this study, we compared patterns of dental antibiotic prescribing during 2017 in several regions of the world: Australia, England, and North America (United States and British Columbia, Canada).

Method

This study was a population-level analysis of dental antibiotic prescribing between January 1 and December 31, 2017. Metrics to assess the quantity of antibiotic use were selected from an international consensus of outpatient quantity metrics. Reference Versporten, Gyssens and Pulcini10 Prescriptions per defined population counts the number of antibiotic items without considering the daily dose or duration of the antibiotic course. Reference Versporten, Gyssens and Pulcini10

Dispensed systemic antibiotic prescriptions from outpatient pharmacies, community, and mail-service pharmacies prescribed by dentists in Australia, England, the United States and British Columbia were included. The drugs were grouped by class: penicillins, cephalosporins, lincosamides (which includes clindamycin), macrolides (which includes erythromycin and azithromycin), nitroimidazoles (which includes metronidazole), tetracyclines, and others (which includes trimethoprim with sulfamethoxazole, spiramycin, and quinolones).

Data sources

Data for antibiotics dispensed by pharmacists to dental patients in Australia were accessed from the Department of Health relating to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. 11 Greater than 90% of these prescriptions are from the community setting, which is the main source of dental prescriptions. 12 The 2017 mid-year population size (24,598,900) was obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. 13

Data for antibiotics dispensed by community pharmacists to dental patients in England were accessed from the National Health Service Digital Prescription Cost Analysis. 14 These data relate only to antibiotics prescribed to dental patients who receive care through the publicly funded National Health Service. The 2017 mid-year population size (55,619,430) was obtained from the UK Office for National Statistics. 15

The US data relating to antibiotics prescribed by dentists were obtained from IQVIA LRx and included those who were commercially insured, used Medicare or Medicaid, and who paid cash. These data included 92% of all outpatient prescriptions dispensed in the United States. The 2017 population size (325,147,121) was obtained from the US Census Bureau. 16

Prescribing data relating to dentists in British Columbia were obtained from the BC Ministry of Health, PharmaNet, a database capturing 99% of outpatient prescriptions in the province. 17 The 2017 mid-year population size (4,817,160) was obtained from Statistics Canada. 18

No ethics approval was required from the Australian Department of Health because these data were publicly available to facilitate health policy research and analysis. Data from England were available via request to the National Health Service under the UK Freedom of Information Act 2000. Use of the National Health Service Business Services Authority data sets is licensed under the terms of the Open Government License for Public Sector Information. The University of Illinois at Chicago Investigational Review Board deemed that this study was exempt from review and informed consent. The University of British Columbia Institutional Review Board approved the protocol used in this study (no. HO9-00650).

Outcomes

Three outcomes for each country were described: (1) rate per 1,000 population of antibiotic prescription items dispensed, (2) relative proportions of each antibiotic class, and (3) rate per 1,000 population of each antibiotic type.

Statistical analysis

Data and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Comparison of proportions of prescriptions and each specific antibiotic by country were analyzed using the χ2 or the Fisher exact test, and a 2-sided P value ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

In 2017, dentists in the United States prescribed 23.6 million antibiotic items, 3.0 million in England, 0.8 million in Australia, and 0.3 million in British Columbia. As shown in Figure 1, dentists in the United States had the highest rate of antibiotic use (72.6 antibiotic items per 1,000 population) and Australia had the lowest rate of antibiotic use (33.2 antibiotic items per 1,000 population) during 2017.

Fig. 1. Rate of dental antibiotic prescribing per 1,000 population by country.

Relative proportions of each antibiotic class

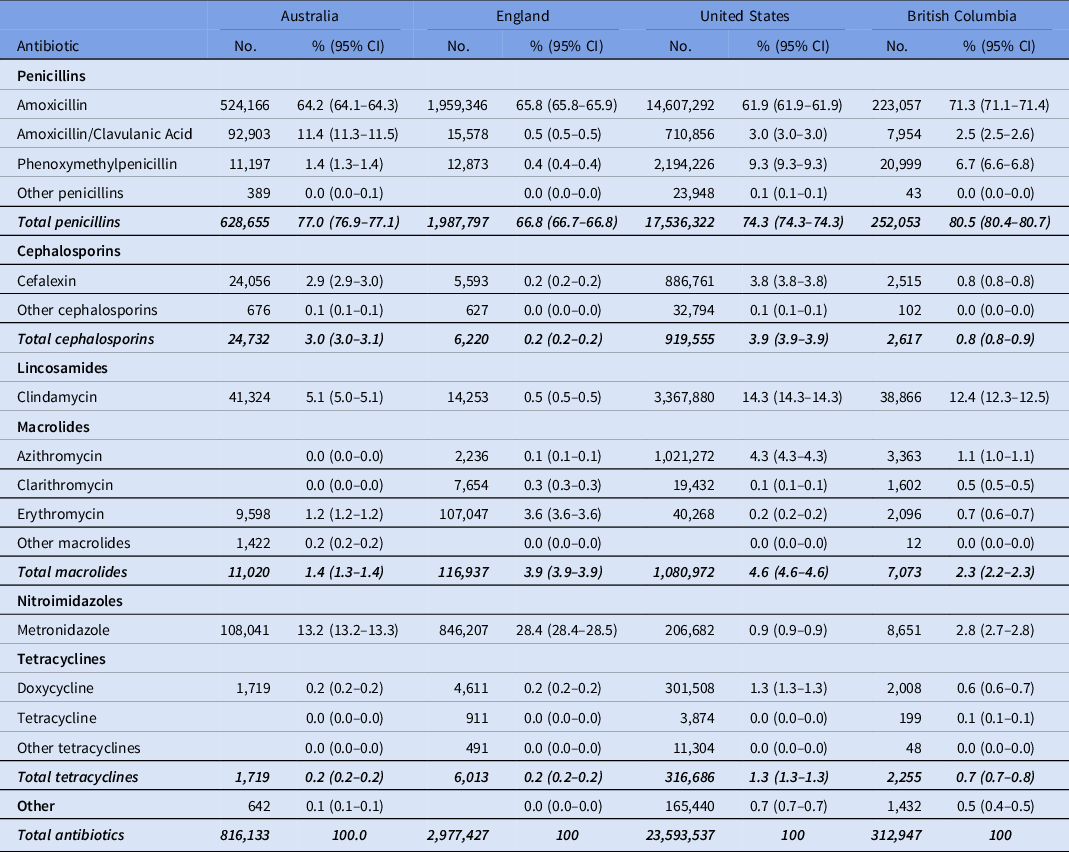

As shown in Table 1, the penicillin class of antibiotics was the most prescribed in each country (highest at 80.5% in British Colombia and lowest at 66.8% in England). Nitroimidazoles (ie, metronidazole) comprised the second most frequently prescribed class of antibiotics in England (28.4%) and Australia (13.2%). Lincosamides (ie, clindamycin) comprised the second most frequently prescribed class of antibiotics in the United States (14.3%) and British Columbia (12.4%). Macrolides comprised the third most frequently prescribed class of antibiotics in the United States. Cephalosporins were prescribed more often in the United States (3.9%) and Australia (3.0%) than in British Columbia (0.8%) and England (0.2%). Tetracyclines were rarely prescribed in any of the countries.

Table 1. Relative Proportion of Dispensed Antibiotic Types in 2017 by Country

Note. CI, confidence interval.

Rate per 1,000 population by antibiotic type

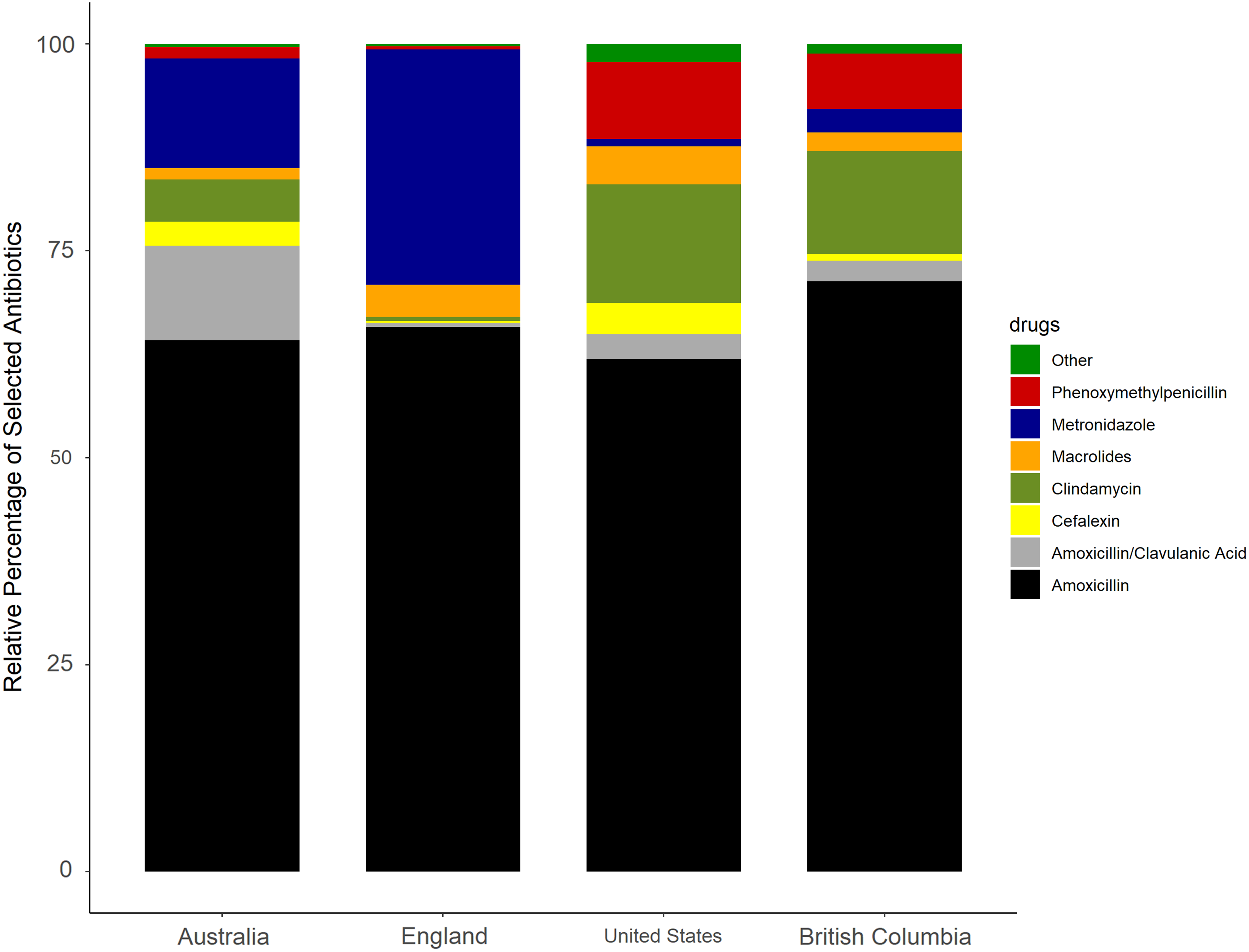

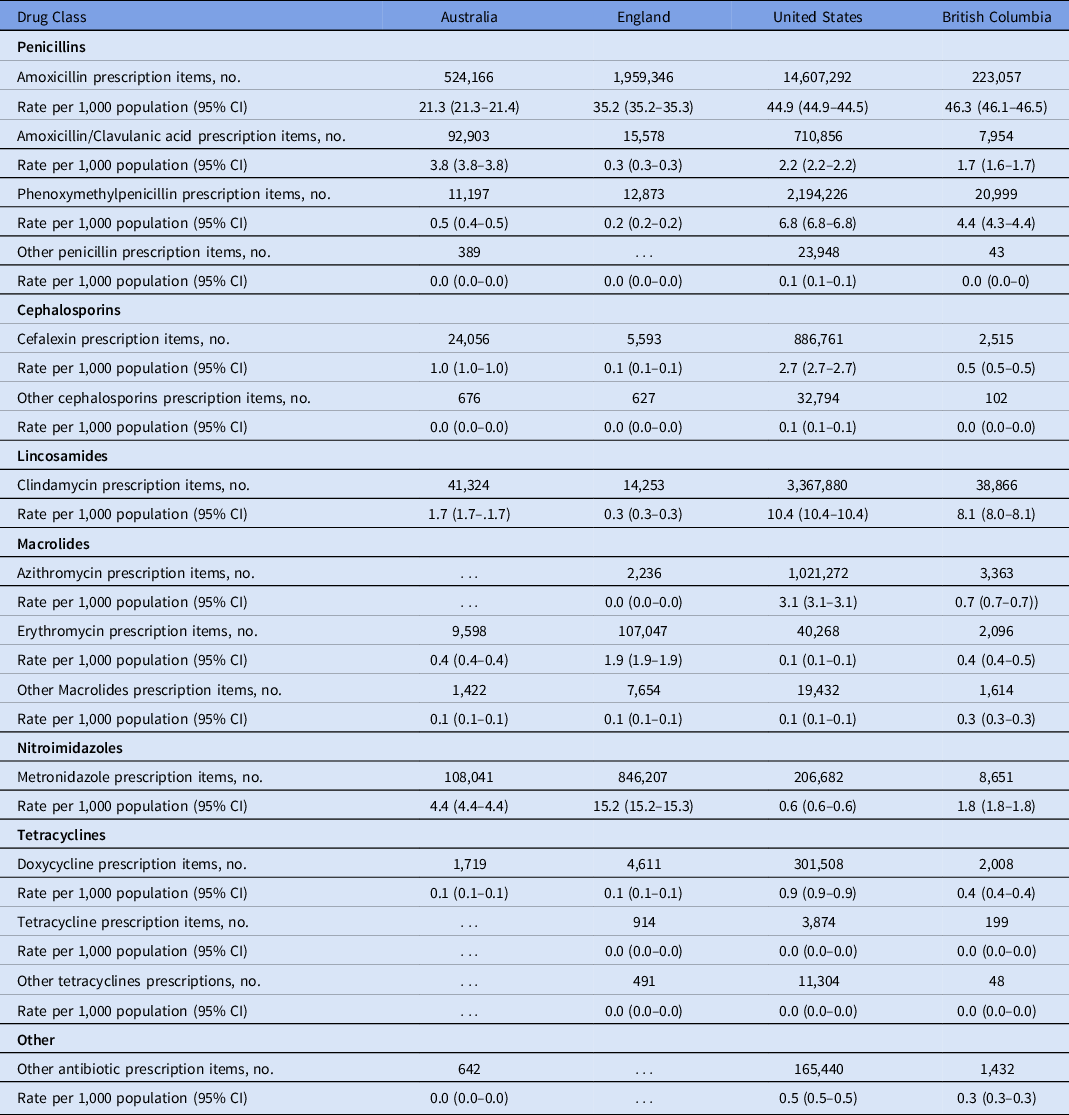

As shown in Figure 2, the highest rate of antibiotic prescribing per 1,000 population in each country was amoxicillin; British Columbia had the highest rate (46.3 prescription items per 1,000 population) and Australia had the lowest rate (21.3 per 1,000 population) (Table 2). The rate of prescribing for the broader-spectrum antibiotic amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was highest in Australia (3.8 per 1,000 population) and lowest in England (0.3 per 1,000 population). The narrowest-spectrum antibiotic, phenoxymethylpenicillin, was most commonly prescribed in the United States (6.8 per 1,000 population) and least commonly in England (0.2 per 1,000 population).

Fig. 2. Relative proportions of each antibiotic type by country.

Table 2. Rates of Dental Antibiotic Drug Class Prescribed per 1,000 Population in 2017 by Country

Note. CI, confidence interval.

Metronidazole was the second most frequently used antibiotic in England (15.2 prescription items per 1,000 population) and Australia (4.4 per 1,000 population). Clindamycin was the second most frequently used antibiotic in the United States (10.4 items per 1,000 population) and British Columbia (8.1 per 1,000 population). The rate of cephalexin use was highest in the United States (2.7 per 1,000 population) and lowest in England (0.1 per 1,000 population). Macrolides were rarely used in Australia or British Columbia; in the United States, azithromycin was the most prescribed macrolide (3.1 per 1,000 population) and in England it was erythromycin (1.9 per 1,000 population). Doxycycline was the most prescribed tetracycline; the highest rate was in the United States (0.9 items per 1,000 population) and the lowest rates were in Australia and England (both 0.1 per 1,000 population).

Discussion

In 2017, wide variation existed in the patterns of antibiotic prescribing by dentists. The rate per 1,000 population in the United States was twice that in Australia, which had the lowest prescribing rate. Although amoxicillin was the most prescribed dental antibiotic in all 4 countries, clindamycin was the second most prescribed dental antibiotic in the United States and British Columbia compared to metronidazole in Australia and England. Other broad-spectrum agents, such as amoxicillin-clavulanate and macrolides (eg, azithromycin), which have higher resistance potential, were also used by dentists.

The variation in the rates of antibiotic prescribing among the 4 countries does not seem to be explained by differences in dental health, but it may be related to differences in the prophylactic use of dental antibiotics aiming to protect people at risk of distance site infections during operative dental procedures. Similar levels of dental health have been previously described using well-established epidemiological outcomes measures of oral health including missing teeth, edentulousness, number of carious teeth, and degree of caries experience. Reference Mejia, Elani and Harper19,Reference Slade, Nuttall and Sanders20 Many factors are known, however, to influence dental antibiotic prescribing, including access to dental treatment and the existence of (or knowledge about) national guidelines. Reference Suda, Calip and Zhou4,Reference Thompson, McEachan and Pavitt21–Reference Shah, Wordley and Thompson24 Further research to explain the reasons for the significant variation identified is needed.

Variation in national guidelines: Indications

Dental antibiotic guidelines around the world for therapeutic indications are generally based on the principles of draining infections and removing the cause, with procedures such as dental extraction. Reference Lockhart, Tampi and Abt25–27 For the prevention of conditions such as infective endocarditis, antibiotic prophylaxis (a single oral dose of amoxicillin 3 g or clindamycin 600 mg) is indicated by guidance in most countries, including Australia, the United States, and Canada, 26,Reference Nishimura, Otto and Bonow28 but it is not routinely recommended by guidelines used in England. 29 The extent to which this fundamental difference in guideline philosophy accounts for differences between England and the other nations in this study is unclear, although it is likely to be relatively small. Reference Thornhill, Dayer and Prendergast30,31 In the United States, high rates of prophylactic overprescribing (not in accordance with guidelines) are known to occur. Reference Suda, Calip and Zhou4 Suggested explanations include the perioperative use of antibiotics to prevent complications of oral surgery procedures, such as the placement of dental implants and the removal of third molars. Reference Marra, George and Chong6

Ensuring that national guidelines are clear about therapeutic, prophylactic, and perioperative indications will be important to reducing variation in the rates of dental antibiotic prescribing internationally. 27,Reference Thornhill, Dayer and Prendergast30,31

Variation in antibiotic types

Although amoxicillin is the most prescribed antibiotic in each of the 4 countries, in Norway and Sweden the most prescribed antibiotic is phenoxymethylpenicillin Reference Smith, Al-Mahdi and Malcolm32 and in Japan cephalosporins and macrolides are most often prescribed. Reference Ono, Ishikane and Kusama23 Macrolides were prescribed by dentists in all 4 countries studied: erythromycin most often in England and azithromycin most often in the United States. The World Health Organization (WHO) has introduced 3 classifications of antibiotics as part of its efforts to tackle antibiotic resistance: the AWaRe classification (ie, Access, Watch, Reserve). 33 Antibiotics which offer the best therapeutic value while minimizing the potential for resistance are included in the ‘Access’ group. Antibiotics that are prone to selecting for resistance are included in the ‘Watch’ group. Watch-group antibiotics (including macrolides) should be prioritized in antibiotic stewardship programs to minimize their use. 33

High levels of resistance to erythromycin are associated with bacteria commonly isolated from odontogenic infections and increased incidence of side-effects (eg, gastrointestinal adverse effects) and drug interactions in some parts of the world. 27 Dental antibiotic stewardship programs, which focus on reducing the unnecessary use of antibiotics generally and optimizing the use of macrolide antibiotics specifically, are needed worldwide.

Adverse drug reactions to oral antibiotics commonly prescribed by dentists are also important considerations. Common antibiotic-related adverse reactions include nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. More serious outcomes include allergy, anaphylaxis, bacterial resistance, and Clostridoides difficile infection. Clindamycin use in dentistry has been associated with a significant number of nonfatal and fatal adverse drug reactions, Reference Thornhill, Dayer and Prendergast30 and community-associated Clostridoides difficile infections have been related to dental use of clindamycin in the United States. Reference Bye, Whitten and Holzbauer34 Our finding that clindamycin was prescribed in the United States and British Columbia far more often than in England is significant and highlights the importance of a review of dental antibiotic guidelines to ensure that they consider the risks as well as the benefits for patients.

Patient-reported penicillin allergy is the reason dentists in Australia and the United States prescribe clindamycin. Reference Lockhart, Tampi and Abt25,26 In England, macrolides are recommended for patients who are allergic or unable to tolerate penicillin or metronidazole antibiotics. 27 This problem is significant because penicillin allergy is reported in 10%–20% of patients, yet a high percentage of penicillin allergy labels on medical records are likely to be erroneous. Reference West, Smith and Pavitt35 Providing pathways for dentists to refer patients for penicillin-allergy testing and, where appropriate, delabeling should further improve patient safety by reducing the use of antibiotics that are known to be associated with increased incidence of Clostridoides difficile, more drug-resistant bacterial infections, longer hospital stays, greater frequency of hospital readmissions, poorer clinical outcomes, and increased economic costs. Reference West, Smith and Pavitt35 In addition, national dental antibiotic guidelines should be updated to consider the most recent evidence relating to appropriate alternative drugs for people with penicillin allergies, such as cephalosporins. Reference Trubiano, Stone and Grayson36

Updating and implementing national guidelines

The importance of national dental antibiotic guidelines that consider the local context including rates of resistance to antibiotics to particular antibiotics, the availability of quality-assured antibiotics, and access to dental services has been highlighted by the FDI World Dental Federation. Reference Thompson, Williams and Pulcini1 In particular, guidelines appropriate in high-income countries may not be appropriate in low- and middle-income countries where access to dentistry and high-quality antibiotics may differ. As a result, dental antibiotic prescribing guidelines around the world will continue to vary.

Antibiotic stewardship measures aim to optimize antibiotic prescribing in accordance with national guidelines. They have been advocated as one way that dental teams can contribute to global efforts to tackle antibiotic resistance. Reference Thompson, Williams and Pulcini1 Because factors driving antibiotic prescribing decisions are complex and numerous, there is no ‘one size fits all’ solution: combinations of clinical audits, feedback, and educational outreach visits have been shown to be particularly effective in primary dental care. Reference Loffler, Bohmer and Hornung37 A systematic review of metrics for evaluating antibiotic stewardship programs across primary health care revealed that dental studies focused solely on rates of antibiotic prescribing, whereas a wider set of outcomes, such as adverse outcomes and patient satisfaction, were employed in other primary healthcare settings. Reference Teoh, Sloan and McCullough38 Further research to develop international consensus for a set of dental antibiotic stewardship core outcomes is needed.

This study had several limitations. Each nation collects and reports its antibiotic prescribing data in different ways. The data reported in this study for Australia, England, and British Columbia were obtained from public health data sources, whereas US data are proprietary. As highlighted in a similar study across Northern Europe, Reference Smith, Al-Mahdi and Malcolm32 the figures for each country are known to be underestimates of the total number of antibiotics prescribed to dental patients and, in particular, the English data do not include prescriptions for patients receiving private treatment. This factor also applies to the Australian data, although these numbers are estimated to be low because all common antibiotics prescribed for dental treatment are listed on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. 11 In contrast, the British Columbia PharmaNet captures all outpatient prescriptions, irrespective of payer, and there is reasonable confidence that it captures most dental use. 17

Importantly, these data include only antibiotics dispensed by pharmacists. Around the world, not all antibiotics are supplied to patients by pharmacists. In England, private dentists can supply antibiotics directly to patients, and while the actual quantity is unknown, it has been estimated that this may represent another 25% of dental antibiotics that are currently uncounted. 39 Dentists in Australia may also dispense antibiotics directly, although dental dispensing of medicines is thought to be rare. Regulations in Canada and the United States prevent dentists from supplying antibiotics. However, in many countries (especially low- to middle-income countries), >60% of antibiotics can be purchased directly without a prescription and not necessarily through a pharmacy. Reference Batista, Rodrigues and Figueiras40 The inability to quantify the potentially numerous antibiotics supplied directly is a significant issue, and high-priority action is required to ensure that systems are in place to monitor all antibiotic use in all countries, irrespective of payer or supplier.

Although the routinely collected data included in this study were assessed to be the best available to quantify the amount of antibiotics dispensed to dental patients, it was not possible to assess the indication (eg, therapeutic or prophylactic use) for the prescription, nor to assess the appropriateness of prescribing. Furthermore, differences between national guidelines make it difficult to compare antibiotic prescribing between countries. The necessity for national guidelines that consider the local context, such as patterns of resistant bacteria and access to dental procedures (as advocated by the FDI World Dental Federation), present considerable difficulty in drawing conclusions about rates of overprescribing across the international dental community. Further research is needed to identify how best to present international comparisons for dental antibiotic prescribing to drive quality improvements using the proposed core outcome set for dental antimicrobial stewardship.

In conclusion, concerning differences exist in the patterns of dental antibiotic prescribing around the world. Significant opportunities exist for the global dental community to contribute to international efforts to tackle antibiotic resistance, including by changing from broad-spectrum antibiotics (eg, amoxicillin/clavulanate) to narrower-spectrum antibiotics (eg, phenoxymethylpenicillin) and by reducing the use of WHO ‘Watch’ antibiotics (eg, azithromycin). The dental profession can also contribute to improvements in patient safety by minimizing the use of antibiotics associated with increased adverse drug reactions (eg, clindamycin) by reviewing guidelines, auditing compliance, and assisting in efforts to delabel people who identify as penicillin allergic. Dental antibiotic stewardship programs are urgently required as part of national responses to delivering the WHO global action plan on tackling antimicrobial resistance. Further research to understand locally relevant factors driving unnecessary dental antibiotic prescribing in each country is needed to support the development of context-appropriate stewardship solutions to the global problem of antibiotic resistance. To enable improvements in the quality of dental antibiotic prescribing around the world, it is vital that governments ensure that they have systems to capture all data relating to antibiotic prescribing, irrespective of payer or supplier.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the BC Ministry of Health for providing the data on antimicrobial consumption for British Columbia, Canada. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the US government, or of IQVIA or any of its affiliated entities. The statements, findings, conclusions, views, and opinions contained and expressed in this article are based in part on data obtained under license from IQVIA (source: LRx January 2017 to December 2017, IQVIA Inc). All rights reserved.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research integrated academic training program (to Thompson), the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship (grant no. 241616 to Teoh), and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. R01 HS25177 to Suda and Hubbard).

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; nor the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of interest

A. Campbell is an employee of IQVIA. All other authors report no conflicts of interest related to this article.