Countries do not only fall into different categories of capitalist production and welfare regimes, but also different categories of housing regimes. In a capitalist country such as Germany, the entire real estate sector represented 22 percent of all existing German companies in 2006, 10 percent of all employees and 8 percent of all sales, while residential real estate amounted to 59 percent of the estimated 6.6 trillion euro value of German real estate in 2008 [Voigtländer et al. 2008: i-iv] and 39 percent of private net wealth [Piketty and Zucman Reference Piketty and Zucman2013]. In spite of this sector’s importance in the economy, comparative research on capitalist or welfare systems has accorded surprisingly little attention to this particular sphere of institutions, production, and welfare with the exception of specialized scholarship on housing.

Since the late 1960s [Donnison Reference Donnison1967], housing scholars have offered various models for grouping oecd countries in different clusters, according to the countries’ percentage of homeowners, of private and public tenants [Kemeny Reference Kemeny1981]; their modes of land development (private, public, mixed, or anarchic) [Barlow and Duncan Reference Barlow and Duncan1994]; their degree of decommodification of housing supply [Harloe Reference Harloe1995]; and their degree of mortgage indebtedness [Schwartz and Seabrooke Reference Schwartz and Seabrooke2008]. Rough correlations between types of welfare state regimes and types of housing regimes have been found [Arbaci Reference Arbaci2007, Castles and Ferrera Reference Castles and Ferrera1996, Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2005]. It would be a mistake to believe that these classification attempts yielded typologies as established as those of the production or welfare regimes, and proponents of a convergence thesis with regard to housing regimes would consider any attempt at such typology as being altogether futile [Kemeny and Lowe Reference Kemeny and Lowe2005].

However, all classifications to date seem to agree that Germany and the United States fall into entirely different housing market and policy regimes, although their industrial, urbanization, and city-system developments are often comparable. Germany has been one of the countries with the lowest rates of homeownership in international comparisons. The country has densely constructed cities of apartment buildings, where land development has been municipally regulated and a great deal of subsidizing took place in the public and private construction of rental property between 1920 and the 1970s. Furthermore, federal tenant protection legislation has been in existence since 1914. For its part, the United States embarked on the homeownership path: it suburbanized its cities by encouraging the construction of single-family houses on privately developed land with the support of a subsidy scheme favoring home-owning households during the New Deal. While the German homeownership rate moved from an estimated 25.7 percent in 1950 to today’s level of 45.7 percent [Glatzer Reference Glatzer1980: 246, Zensus Reference Zensus2011], the US homeownership rate rose from 43.6 percent in 1940 to almost 70 percent on the eve of the last financial crisis (US Census). At the same time, federally supported public housing hardly moved beyond the 5 percent threshold of new construction, and US federal rent legislation remained entirely nonexistent except in moments of crisis. These are only five of the important housing-related dimensions in which the two countries—and possibly others along the English-German language divide—systematically differ.

Instead of adding to the descriptive task of typologizing, this article will directly come to grips with the question concerning the causes for the differences between the two countries in their housing regimes. Why did Germany tend to become a country of tenants with a housing policy directed at private and public rental construction? Why, on the other hand, did the United States turn into a homeownership country? The not quite obvious answer to these questions lies in the realm of historic institutionalism: I will begin by arguing that it was the type of housing-specific financial institutions that emerged in the period of strong urbanization between 1870 and 1914 that channeled capital into either tenant-friendly apartment buildings or homeownership-advancing single-family houses. In short, the housing form followed finance.Footnote 1 More specifically, the early emergence of building societiesFootnote 2 in the United States favored the construction of single-family houses. In Germany, this institution did not become significant until the post-World War II (WWII) era and then in a different form, while the cities of apartment buildings built during the Imperial period were mostly financed by bond-financed mortgage banks. At the same time, non-profit housing associations began constructing apartment buildings locally for the lower-income strata. The combination of these two institutions––non-profit associations and mortgage banks––was one of the reasons why building societies of the British-American type did not arise in Germany. Note that these developments occurred in both countries prior to the first housing-related governmental interventions.

I will continue my argument by showing that the different types of housing institutions that emerged in the two countries pre-determined the way that government housing policy was designed, once the housing crises of the postwar periods and the Great Depression forced governments to react. Thus, it is not necessarily the different housing ideologies, the political system, or economic variables that account for the differences in the resulting housing policies. Rather it was the type of institutions (and their lobbies) that already had a legacy in housing provision that mattered, for governments found these most easy to address. While other factors such as differences in urban planning, city history, land availability, and living standards were certainly also important for the divergent housing trajectories, I will argue for a distinct explanatory power of these historic housing institutions.

The article makes three distinct contributions. It introduces the rather neglected field of housing into the realm of comparative political economy by using some established explanatory approaches from historic institutionalism to explain housing phenomena. Then, in order to provide an institutional answer to a question that has been overlooked, it examines two empirical country cases of different housing regime types and demonstrates that housing finance is the major variable that explains their differences. Finally, the article goes beyond the arena of housing and highlights the importance of institutional legacies in explaining governmental policies. Differences in early nineteenth century reforms, for example, may become crucial in explaining governmental social policy intervention in the twentieth century.

After introducing the three different housing-related institutions—savings and loan associations (slas), mortgage banks, and non-profit associations—in the following section, I will describe the origins of the slas in the United States (section 2). I will then explain why non-profit associations postponed the rise of an sla type of institution in Germany (section 3). Section 4 then returns to the United States to describe what prevented the rise of a similar independent non-profit housing movement there, while section 5 explains why capital-tapping mortgage banks arose in Germany, but not in the United States. Section 6 shows how the first housing policies can be seen as perpetuating the institutional legacies in both countries rather than breaking with earlier patterns. While this section refers only to the West German and the reunified German institutional development—East German housing policy was Sovietized and later integrated into the West German housing institutions after 1989—the previous sections refer to institutional developments before World War II in all of Germany. I conclude by generalizing the findings for other German- and English-speaking countries and point to some implications of my findings for further research.

The threefold distinction of organized housing finance circuits

Housing, like many durable goods, requires capital investments that go beyond usual consumption expenditure and, much like larger infrastructural investments, requires a great amount of borrowed capital. However, compared with rates of profit to be made in other industries, housing has usually been only of secondary importance and therefore in permanent need of more capital, especially in times of general scarcity. This profitability problem is compounded by the fact that there are more people seeking long-term mortgages than there are people making long-term investments or deposits. This “maturity-mismatch” problem [Schwartz Reference Schwartz2014b] surfaces either within financial intermediaries when they absorb short-term money to provide long-term mortgages or when borrowing households can only take out short-term mortgages, which have to be renewed more often. Traditionally until the nineteenth century, mortgage markets in most countries were organized through interpersonal networks linked by intermediaries such as notaries or lawyers. But with the growth of banks and finance in the later nineteenth century, the role of organized banking capital in the provision of mortgages became more important [Clemens and Reupke Reference Clemens and Reupke2008; Fishback, Rose and Snowden Reference Fishback, Rose and Snowden2013: 11].

There were two ideal-typical ways to provide for private housing capital through banks: to create specialized local circuits of housing capital that were shielded from competition or to access larger capital markets of mostly risk-aversive investors. In the first case, that of slas or the German Bausparkassen (building societies), local bank deposits, often reinforced through compulsory saving plans, recruited the necessary capital for the long-term housing investment. In the second case of bond-issuing mortgage banks, the necessary capital and time commitments were obtained by maturity-matching bonds sold on capital markets and believed to be without risk. Thus, mortgage bonds constituted a product similar to those that nineteenth century investors were familiar with—the government or railroad bonds.

A third, non-profit option for providing housing capital beyond these two private banking circuits is represented by housing associations, which were founded either as philanthropic entities from above or as religiously or union-inspired cooperatives from below. Building cooperatives are owned by members who contribute capital collectively in order to have the cooperative build their housing units. In contrast to the somewhat misnamed British building societies or American slas—which do not build themselves but help finance members’ building activities—building cooperatives constitute a separate entity commissioning or even constructing their own housing units. While members of slas or Bausparkassen only save money collectively but allow members to build housing units individually, building cooperatives pool capital to both construct and rent out units collectively. Even though they pool capital for housing construction, they are not a housing finance institution in the narrow sense but rather fulfill the role of a builder and landlord borrowing considerable sums.

The upshot of this threefold distinction of housing finance institutions into slas, mortgage banks, and non-profit institutions is that they do not act as a neutral channel through which savings flow into the housing sector; instead they establish selective circuits that favor either rental constructions of larger apartment buildings or small houses for owner-occupiers. More specifically, the local slas in American communities, much like the later German Bausparkassen, became the backbone of small-unit neighborhood housing, primarily for homeowners, while the bond-financed German mortgage banks and the non-profit movement—both absent in the United States—built dense German cities of apartment buildings. The correlation between finance institution, building type, and tenure (i.e. rental or ownership) status is never exact, but it is historically well supported and sometimes even legally prescribed. With the expansion of retail banking, banking concentration, and the end of very specialized banking beginning around 1980 [Ball Reference Ball1990; Diamond and Lea Reference Diamond and Lea1992], the argument grows successively weaker that housing-finance institutions have an autonomous effect on building and tenure types. Nowadays the persistence of these institutions and, more importantly, the persistence of much of the housing stock and urban structure their historic mortgage capital helped to construct suffice to ascribe these institutions a historical causal role in the creation of long-lasting housing regime differences. In the following, I will explain from a historical perspective why the United States took the sla-dominated path, while Germany chose the path with mortgage banks and non-profits as important housing institutions.

The emergence of the slas in the United States

Building societies, that is, collective thrift institutions offering loans to their members, have their origins in Friendly Societies of eighteenth century England; the first known American building society, founded in Frankford, Pennsylvania, in 1831, is a direct outgrowth of this tradition. At first, they were usually “fully terminating,” meaning that the society did not survive the construction of the last member’s house. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the so-called serial plan, followed by the Dayton plan and others, slas became permanent institutions that opened up to serve strictly saving members in equal measure, thus competing with other thrift institutions for deposits. With these changes, the institutions were gradually transformed from member-based, cooperative-like clubs to stronger, bureaucratized bank-like institutions that did not have to rely on the thrift discipline of all individual members [Haveman and Rao Reference Haveman and Rao1997].

With these developments, thrifts began to differ from the German Bausparkassen, for the latter were founded as cooperatives for saving and lending to members only, in which an obligation to save ex-ante existed and it was impossible to exit without the loss of all prior savings [Block Reference Block1931], principles that persist in relaxed form to this day. This stronger emphasis on ex-ante savings and the cooperative-like identity of members and borrowers are the main features of the so-called Continental form of slas which spread from Germany into other parts of Europe in the interwar era [Effosse Reference Effosse2003: 180]. The main difference between the Continental types of slas and those typical of Anglophone countries is that the former do not open themselves to the capital market, beyond their members’ deposits, and that members therefore have to save more capital themselves. The American slas also did not restrict themselves to issuing second mortgages like their later German counterparts, but became the primary mortgage lending institution that gradually institutionalized the amortizing mortgage at a time when it was still common to pay mortgages back in lump sums that had been saved in mutual or savings banks. The regular payments corresponded well with the regularizing paychecks of the rising working class and were less demanding with respect to long-term foresight, while still instilling attitudes of thrift [Daunton Reference Daunton1990: 260]. slas introduced this form of longer-term amortizing mortgages with relatively high loan-to-value ratios (ltv)Footnote 3 before the governmental insurance introduced by the New Deal standardized this type of mortgage. While amortizing mortgages or consumer installment credit has become the standard form of credit, the American situation starkly contrasts with that of Imperial Germany, where non-amortizing mortgages were dominant among the mortgage banks [Eberstadt 1920: 425].

A number of conditions were favorable to the rise and spread of slas throughout the United States. First, on the supply side, the American banking system was still in the making in the nineteenth century. Banks moved with the frontier, and regulations often restricted banking activity to local states. slas were technically easy to set up, and their club-like arrangement was welcomed by Americans, who had grown weary of repeated bank failures. Although mutual savings banks existed almost to the same extent as in Europe, especially in New England and the Middle Atlantic region, they certainly did not have branches covering the entire country, and the total number of saving books was smaller than in Europe [Garon Reference Garon2012: 93]. The success of the slas contributed to the decline of the market share held by savings banks even in their home regions and impeded their expansion into new ones [Lintner Reference Lintner1948: 51]. Contrary to savings banks, the slas invested almost 100 percent of their assets into mortgages, not only 50-75 percent, and thus circumvented deposits in investments other than housing. Two aspects made slas the more adaptive type of banking institution outside of the northeast: partially compulsory savings plans were standard at slas, and their members had a strong role in governing the institution, as opposed to banks controlled largely by civic-minded philanthropists.

Moreover, the slas occupied a market niche in the growing banking market. The US postal savings banks, competitors for collecting small savings, did not develop until the twentieth century, while life insurance companies preferred to finance mortgages on farms or commercial property and national banks did not enter the mortgage business before 1900 [Snowden Reference Snowden2003: 164]. Commercial banks did not tend to be an option for most mortgage-seekers because they were specialized in short-term business loans [Behrens Reference Behrens1952]. Both on the deposit-collecting side and the mortgage-lending side, the slas thus encountered far less established structure and competition than their counterparts did in continental Europe, where institutionalized banking had a longer history. Compared with other banks, slas traditionally had the advantage of low transaction costs—for members administrated themselves, at least initially—and of better information and sanctioning mechanisms concerning borrowers, as is shown in the relatively low foreclosure rates recorded in the first sla survey in 1893 [Mason Reference Mason2004: 29]. In the late 1880s, a group of nationally operating slas—referred to as the nationals—arose, aggressively serving mostly cities of low sla density. They made higher profits by serving high-interest areas and cutting back administrative costs. Both the real estate crisis of the 1890s and personal profit-seeking led to the demise of this temporary phenomenon within the same decade, further strengthening the slas’ commitment to localism.

Second, there was a specific demand for these institutions beyond the supply-side factors discussed above. slas filled a social niche in the nineteenth century banking market since workers, women, and immigrants were hesitant to enter the higher sphere of commercial banks, whose services specializing in short-term credit were not in any case tailored to their needs [Bühler Reference Bühler1965: 16; Mason Reference Mason2014]. The SLAs in a city were often as fragmented as its ethnically or occupationally segregated neighborhoods. More generally, SLAs were a local self-help response to the urban lack of capital and credit and to the resulting high interest rates that characterized much of the Western regions in the nineteenth century. Their diffusion could not be taken for granted, however. Some urban centers, such as St. Louis or New Orleans, were entirely devoid of a local sla in 1880 [Snowden Reference Snowden2003: 166]. In addition, it was not only ethnic or class separatism that drove the emergence of new SLAs, but other factors as well, such as the instrumental role of realtors in creating new financial institutions to extend access to credit and to increase demand in their markets [Snowden 1997].

Third, SLAs constituted the institution that was probably most congenial to the ideas described in frontier literature: “[T]he terminating plan was the material realization of a theory of thrift based on the pillars of mutual cooperation and external control” [Haveman and Rao Reference Haveman and Rao1997: 1621]. The image the SLAs projected through early pamphlets such as Edmund Wrigley’s The Working Man’s Way to Wealth—where he counts on every working man becoming his own capitalist—or in the advertisement campaigns of the United States League of Local Building and Loan Associations from 1900 onwards was that of a quasi-religious movement, not an industry, that was on the side of populists, small farmers, and community businesses in that it fought back against the big monopolies. This image also served to legitimize the SLAs’ exemption from corporate taxes in 1894 [Mason Reference Mason2004: 74]. While the big corporate entities served as one common enemy, any kind of more collective form of cooperation, such as the socialist experiments with production cooperatives inspired by Owen or Fourier, were equally condemned [Bodfish 1931: 2]. Generally the joint ownership of housing facilities had a very poor reputation. It thus became difficult to establish modern apartment living for the upper middle classes as it was denounced as being communist [Cromley Reference Cromley1990: 20; Wright Reference Wright1983: 145].

Finally, the sla was also supported by quite a variety of promoters, which made it a flexible partner in various coalitions. First of all, it was “promoted with missionary zeal by a vocal group of ‘building and loan men’ [local real estate businesses] who extolled homeownership as the means by which workers could better themselves and their communities” [Snowden Reference Snowden2003: 170]. A second external promoter was found in the Progressive movement and among housing reformers who also appreciated the SLAs’ role in integrating immigrants and decentralizing government. Ironically, Progressivist values seemed to have promoted the adoption of the Dayton plan in the SLAs that opened them to external savers and borrowers and whose increased flexibility made more professional management necessary. As a result, SLAs went from being community clubs to becoming trusted banking institutions [Haveman, Rao and Srikanth Reference Haveman, Rao and Paruchuri2007; Zucker Reference Zucker1986].

The SLAs’ causal role in furthering homeownership is hard to deny at first: they raise new capital and actually make it accessible for the purpose of constructing owner-occupied, single-family homes. The great majority of their mortgages flow into financing family homes, and their promotional activity, jointly with the realtors’ organizations, has been said to create a greater demand for homeownership. Even if many of the awarded mortgages have also gone toward the construction of rental units, the dominance of the single-family dwellings smoothed the way for easy conversions to owner-occupied units later. Moreover, much single-case historical evidence from the period between 1890 and 1930 suggests that the rising number of SLAs, their growing membership, and increasing assets in mostly urban areas were behind the rise in the mortgage indebtedness that special censuses in 1890 and 1920 revealed. The decline of the national percentage of homeownership through urbanization was also beginning to be compensated by rising urban homeownership rates [Snowden Reference Snowden2006b]. In the Lynds’ study of “Middletown” [1929: 104f], for instance, SLAs come into play from 1889 onwards and were estimated to finance 80 percent of new construction in this town, in which single-family homes built of wood were the predominant type of dwelling; 85 percent of sla members had a working-class background, and overall mortgage indebtedness was growing.

This anecdotal evidence often cited about the sla–homeownership nexus, which even found its way into popular culture through Frank Capra’s 1946 film It’s a Wonderful World, can be supported by a more systematic regression of the SLAs’ mortgage-market share on the percentage of single-family homes in 50 American cities in the 1930s. The unique historical data come from two surveys undertaken by the Civil Works Administration in the 1930s, namely the Real Estate Inventory and the Urban Financial Survey.

The following ols regression includes typical explanatory variables associated with the predominance of single-family homes, particularly the city’s size, its geographical location, demographic composition, and economic position. Car ownership should control for the degree of suburbanization. The percentage of SLAs in the mortgage market, controlled for mortgage interests, has a significant effect on the predominance of single-family homes in the housing stock; the overall regression explains 66 percent of the variance.

Table 1 OLS (n = 50). Dependent variable: percentage of single-family house structures in housing stock

Source: See text.

The development of German non-profit associations and the belated emergence of Bausparkassen

While a large network of local SLAs had developed in the United States and in most English-speaking countries by the 1920s, Germany and much of the European continent did not begin to develop a similar institution until the interwar period. The idea of encouraging thrift in workers by having them join an sla for the purpose of becoming the owners of their own homes was historically not unknown in Germany. The conservative reformer Victor Aimé Huber mentioned the institution for the first time around 1850, and both national-liberal reformers like the statistician Ernst Engel and members of the liberal Kongress deutscher Volkswirte (Congress of German Economists) spoke in favor of it [Müller Reference Müller1999: 48ff]. Very few examples of SLAs in Germany, however, are reported prior to their successful establishment in the form of the Bausparkassen in the 1920s. In the two individual cases of SLA institutions of the Anglo-American type, the SLAs ultimately failed because members did not pay contributions regularly and because they generally lacked capital [Müller Reference Müller1999: 54f].

One central reason for this modest development lies in the early and widespread development of Sparkassen (municipally controlled savings banks) in more urban regions and of credit cooperatives for the middle classes, the rural Raiffeisen banks and urban Volksbanken. From the 1860s onwards, these institutions maintained a closely meshed net of deposit-collecting branches covering most of Germany’s potential savers. By wwi, there were more than 3,000 Sparkassen, the rural cooperatives had almost two million members, and there were more than 2,000 urban cooperatives with over a million members [Kluge Reference Kluge1991: 89]; in 1884, the national postal banks constituted yet another branch-based rival to attract small savings. By 1914, roughly 19,000 credit cooperatives constituted the largest part of the cooperative movement [Aschhoff and Henningsen Reference Aschhoff and Henningsen1995: 30]. The founders of both types of cooperatives, Schulze-Delitzsch and Raiffeisen, were motivated by liberal philanthropy and social Catholicism to include low-income classes in the financial system; in doing so, they absorbed the clientele of potential SLAs. In contrast to the SLAs, the professionalization of cooperatives, however, transformed them more into small, agriculturally oriented business institutions for the middle classes, who were predominantly the borrowers of cooperatives, whereas workers were involved in credit cooperatives as savers at the most; skeptical attitudes of organized labor towards the cooperative movement in particular and consumption credits more generally may also have played a role [Kluge Reference Kluge1991: 113].

Daunton [1988] shows for the British case that workers rather turned to friendly societies, insuring against basic life risks, rather than to homeownership-promoting SLAs. Similarly, one reason for the absence of German SLAs lies in the existing network of insurance funds, mostly organized by professional groups and remnants of guild-based welfare systems. These funds served to protect their members from the most basic misfortunes of life—accidents, old age poverty, burial expenses (burial funds were already founded in the 1830s [Schneider Reference Schneider1989: 23])—and channeled savings that could have possibly financed housing in a different direction. Already by the 1870s, these funds were attracting two out of roughly four million industrial workers [Kaelble Reference Kaelble1991: 122], before Bismarckian compulsory insurance schemes were set up. In turn, the latter provided 6.8 million citizens with health insurance, 11.5 million with disability insurance, and 16.5 million with accident insurance for a total contribution of 242 million Reichsmarks by 1891 [Reuter Reference Reuter1980].

Private Bausparkassen did not exist in Germany prior to the 1920s, when they were founded by petty bourgeois land reformers. These institutions were soon complemented by public Bausparkassen established by the Sparkassen, which used them to cover riskier second mortgages on top of their own primary mortgages. This confirms the view that existing banks preempted the rise of the sla. The specialization on second mortgages was stipulated by law for all Bausparkassen in the 1930s. This institution, much like the SLAs, linked housing savings to investments in owner-occupied housing units. A calculation of Pearson’s correlation coefficients for the volume of per-capita deposits or mortgages in Bausparkassen and the homeownership rates in the various German federal states (Länder) in 1993 and 2000, for instance, results in values of above 0.6.

From the 1850s on, at a time when SLAs were emerging in the United States, Germany saw the development of the non-profit building association as an increasingly more common institution for financing housing [Bühler Reference Bühler1965: 11]. Until 1889, non-profit building associations were usually founded from above in the legal form of limited dividend companies, even with the Prussian king as protector and capital donator. The reformist origin of many of these companies guaranteed them a certain access to capital, which was always in short supply; the lack of capital was also the reason why the original plan to spread homeownership among German workers by way of a rent-to-buy scheme often ended up in the more cost-effective creation of non-profit rental units [Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1991: 66], much lamented by reformers who sought to attain a home-owning working class through British-like building societies [Sonnemann and Lange 1865]. The Berliner gemeinnützige Baugesellschaft (Berlin Non-Profit Building Society) of 1848, for instance, owned many buildings with up to ten dwelling units [Jenkis Reference Jenkis1973: 66]. Private capital was not available since mortgages on privately financed rental housing, which were offered as securities by the private mortgage banks, could offer much higher returns than the 4 percent philanthropy. But often workers were not willing to tie their capital to limited-dividend societies or cooperative shares because this increased housing costs and decreased labor mobility [Jenkis Reference Jenkis1973: 97].

Cooperatives were the legal form more apt to be founded from below, yet they were also haunted by the legal insecurity concerning the liability of cooperative members for cooperative debt beyond their initial contribution. Whereas early housing cooperatives were almost exclusively directed towards the mutual provision of small, privately owned houses, the Spar- und Bauverein Hannover of 1885 constituted the first cooperative devoted to raising capital for the construction of rental units through savings deposits [Jenkis Reference Jenkis1973: 135ff] and thus heralded a division in the movement between the homeownership- and the renting-direct cooperatives, with the latter becoming majoritarian.

In 1889, a new Cooperative Law (Genossenschaftsgesetz) was passed, which represented a breakthrough for worker cooperatives, for example, because it restricted the liability of cooperative capital. In the same year, old age and invalidity insurance was introduced, and its funds were soon to be used for social purposes favoring the insured [Tennstedt Reference Tennstedt1981: 187]. Both the number of cooperatives and the size of their membership grew. They were eagerly given land grants by municipalities, which were thus largely able to withdraw from the business of constructing housing themselves. There is evidence indicating that the 1880s were a time when Germany stood at the crossroads of the paths leading either to the cooperatives or to the SLAs. It was also when the reformist pastor Bodelschwingh founded the “Bausparkasse for everybody” and thereby coined the generic name of the specialized banks that is used today [Müller Reference Müller1999: 57]. What finally pushed Germany down the road to cooperatives was the persistent lack of capital of SLAs, the far too unrealistic projects of homeownership promoters and the eventual rise of the competing cooperatives thanks to social security funds. The complementary relationship between the funds collected through the compulsory social security schemes and the non-profit housing associations—non-profit associations could receive cheap credit to construct rent-restricted units for lower-income classes—was not directly intended: it was not anticipated by the legislators and was included in the law rather by accident. At first, social insurance funds did not receive any instructions about the criteria to be used for distribution other than the stipulation that the companies had to be non-profit [Bullock and Read Reference Bullock and Read1985: 231f]. As a consequence, a steady 31 to 44 percent of the workers’ social security funds or a total of 3.2 billion Reichsmarks between 1895 and 1913 [Reuter Reference Reuter1980]—augmented by the financing by the separate white-collar insurance of their own housing cooperative Gagfah in 1911—went into workers’ housing, much of which was allocated to the growing limited-dividend companies and cooperatives. While the institutions receiving these funds were only responsible for some 5 percent of the overall pre-wwi housing stock—albeit with much higher percentages in the cities [von Saldern 1979]—they laid the institutional groundwork for the large non-profit and municipal ownership of 23.3 percent of all housing units in 2006 [Voigtländer et al. 2008: 21].

The absence of a strong non-profit housing movement in the United States

Writing in hindsight during the 1930s, the American housing reformer Catherine Bauer remarked that a real housing movement comparable to the European one had been traditionally absent in the United States [Bauer Reference Bauer1974]. It is true that the non-profit idea of housing had not been entirely absent. The major center for limited-dividend companies and cooperatives was the northeast, especially the city of New York, where the first philanthropic housing associations constructed moderate-income housing in the late nineteenth century [Siegler and Levy Reference Siegler and Levy1987]. In 1876, the first American housing cooperative for building apartment houses was founded, but its legal status was such that it catered to upper-classes seeking to live in jointly managed apartment houses. The first cooperative in the European sense––where a joint endeavor is made not only of the purchase of material and construction of houses but also of the management of the constructed units–– did not arise until 1916, when Scandinavian immigrants imported the cooperative idea from their homelands to New York City [Karin 1947]. In these cooperatives, individuals only held shares equal to the value of their occupied housing unit, whereas the cooperative itself held the title over the entire property, which often included common amenities beyond the individual units. This cooperative form, which still makes up a considerable part of Scandinavia’s housing stock is much closer to private homeownership than Continental cooperative forms, where the cooperative does not require the purchase of shares equaling the sales price and where it acts more like a large non-profit landlord.

Yet, in spite of the closeness of American cooperatives to private homeownership, this associational form also did not gain much ground as a potential competitor to the SLAs. “The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics discovered only forty cooperative housing societies in existence during the mid-1920s. All but two of these were in New York City,” where most of these were apartment houses inhabited by Scandinavian immigrants [Lubove Reference Lubove1963: 69].

One reason for this absence certainly lies in the less rapid and different development of the cooperative movement in the United States more generally. Whereas today the American cooperative economy appears to be larger and even has a stronger membership base than in European countries such as Germany [Battilani and Schröter Reference Battilani and Schröter2012], the movement’s form and beginnings were quite different. While cooperatives were developed in European countries especially for consumption, credit, some production, and then housing, these manifestations remained rather rare in nineteenth century America. The most fertile ground for such institutions was rural America, where the various populist farmer movements nurtured the existence of purchase, production and sales cooperatives [Horsthemke Reference Horsthemke1998]. The United States’ reputation as a “nation of joiners,” as observed by Tocqueville, Schlesinger, Putnam and others in reference to Americans’ strong tendency to join associations, derives more from the popularity of (quasi-) religious clubs and movements than from any efforts to do business jointly as a cooperative would [Skocpol, Ganz and Munson Reference Skocpol, Ganz and Munson2000]. The reasons for this systematic difference are complex, but they probably have to do with the prevailing private business solutions and an aversion to too much top-down philanthropy, which was associated with many cooperative institutions. In fact, many of the reasons explaining the restricted development of socialism in the United States might equally explain the relative lack of cooperatives. Cooperative ideas and realizations were certainly not absent in America and especially the northeast witnessed the rise of Raiffeisen-inspired credit unions, consumer and eventually housing cooperatives. The early socialist ideas of Owen, Fourier, or others had even motivated the founding of entire utopian towns, whose survival rate proved, however, to be very low [Benevolo Reference Benevolo1971]. American housing cooperatives, which were created from the late nineteenth century onwards, lacked the vital, sustained support of three key groups: reformers, labor, and eventually the government. Such support was essential if they were to thrive like their German equivalents.

Reformers

Prior to the second generation of housing reformers such as Catherine Bauer, Edith Wood, or Lawrence Stein from the 1920s onwards, American turn-of-the-century reformers did not promote non-profit housing as a real alternative model to the private tenement evils that were the target of much reformer activity [Daunton Reference Daunton1990: 257]. Early American housing reformers were certainly aware of European tendencies, where overcrowding, congestion, and slum problems had a longer history. Prior to wwi and again between the wars, city planners and housing reformers would cross the Atlantic from the United States to Europe, and particularly Germany, when looking for new solutions [Rogers Reference Rogers1998]. American housing reformers either proposed the suburban-family retreat [Fishman Reference Fishman1987: 121], offered model houses at low, philanthropically subsidized 5-7 percent interest rates [Lubove Reference Lubove1962: 34], tried to educate immigrants and workers to help them achieve middle-class living standards in the Settlement House Movement, tried to improve tenement living through tenement commissions such as those headed by Lawrence Veiller in New York [Lubove Reference Lubove1962: 105] or else attempted to uplift downtown areas and populations with outstanding public buildings in the City Beautiful movement [Sutcliffe Reference Sutcliffe1981: 98,108]. In all of these different reformer circles, the absence of non-profit rental housing with decent standards can be considered a negative common denominator. European reformers often sought to extend access to decent middle-class rental facilities to the working classes; American reformers usually rejected that idea from the start.

When reformers of the European type—those associated with Edith Elmer Wood, Catherine Bauer, and generally the members of the Regional Planning Association of America (rpaa)—did emerge about the time of wwi, they could not count on equal support at the municipal, state and federal levels [Von Saldern 1997: 81]. The suggested creation of institutions ranging from national housing banks to municipal land banks in the legislation proposed by Wood in 1913 reveals this institutional void [Lubove Reference Lubove1963: 27]. After wwi, the United States “lacked any governmental machinery to compensate for the collapse of the private building industry, which had assumed exclusive responsibility for satisfying the nation’s housing needs” [Lubove Reference Lubove1963: 18].

Labor

Reformers did not adhere to the idea of non-profit housing subsidies benefitting the lower-income classes, and the mainstream American labor movement was equally disinterested. In European countries, cooperative movements and especially the labor movement collaborated with the housing cooperatives by acting as financial sponsors, organizers, member spill-overs, or even very directly as builders. Socialism and labor movements were, of course, not entirely absent in the United States, especially prior to wwi. Indeed, the Socialist Party of America was much in favor of social municipalism as practiced in Europe. But it was certainly weaker and less well organized than its German counterpart; in particular, the surviving and politically relevant elements exhibited different, often outright pro-capitalist political attitudes.

Private ownership of land has never been fundamentally challenged in the United States, and the critique of large land monopolies or of effortless land gains considered by many to be illegitimate did not lead to effective demands for municipal or state ownership of land or other kinds of land distribution beyond the market as it did in Germany or the United Kingdom [Daunton Reference Daunton2007]. Rather, the dominant reaction was to put restrictions on monopolistic speculators in favor of a more equal distribution of land so as to make everyone a participant in the market. Even Eugene Debs of the Socialist Party proposed more small landownership as a counterbalance to the big corporations [Fitrakis 1990: 24]. These ideas, taken up in the first Land Ordinance from 1785, the Homestead Act of 1862, and the 1920s Zoning Ordinances, were repeatedly defended, first with regard to agrarian land for farmers, then in the second half of the nineteenth century for urban land for industrial workers as well. Both farmer groups and labor unions were often sympathetic to each other’s concerns and used a similar vocabulary. For example, the Knights of Labor, whose strongly Irish and Catholic constituency affiliated itself with the fight for land reform in Ireland, included the demand for a free distribution of land to the people in the preamble of its program in 1878 [Schratz 2011: 30]. But also the American Federation of Labor (afl) was in favor of homeownership and better housing for unionized workers, as is documented in various proceedings from its annual conventions.

There are several reasons why American labor preferred homeownership. One reason, also cited in the debate about the absence or decline of socialism in the United States, is the exceptional culture of the American frontier that provided easy access to property [Foner Reference Foner1984: 60, Harris and Hamnett Reference Harris and Hamnett1987, Lipset and Marks 2000: 24, Turner 1920]. A second reason for American labor’s affinity to homeownership and indifference towards non-profit housing lies in the factual housing conditions. Urban historians generally report higher homeownership rates for workers than for the middle classes before 1900, when cities were not yet socially segregated and the middle class had not yet made the form of tenure a status norm [Garb Reference Garb2005; Simon Reference Simon1996; Zunz Reference Zunz1982]. A third reason for labor’s adherence to the homeownership ideal lies in its association with populist farmer groups. Contrary to Germany [Puhle Reference Puhle1975: 33ff], industrialism aroused various movements of small farmers such as the populist movement that served as examples to the labor movement, kept ideas of egalitarian landownership alive, and fostered fraternization against common enemies such as big monopolies, regressive taxes, and tight monetary policy [Hays 1957: 28f, Prasad Reference Prasad2012: 125ff]. Finally, smaller types of housing such as single-family houses, two-story tenements, or even triple-deckers, meant that less minimum capital was necessary if one wanted to invest in housing than was the case in Germany, where apartment buildings were made up of at least half a dozen inseparable housing units. In times of hardship, one survival strategy of American labor was to invest in owner-occupied housing while renting out parts of it to earn an additional income [Harris Reference Harris1989].

Government

Finally, the various levels of government largely abstained from initiating or supporting this kind of housing provision before explicit housing policy started in the 1930s. American municipalities lacked the tradition of municipal land-banking, which would have helped cooperatives receive implicit subsidies through land provisions and would have solved their location problem, given the rise of ever more excluding neighborhoods. The provision of municipal housing lay even farther beyond the possible competences of American cities. Nor did the federal government, which subsidized homesteads, railroads, and farming through cheap land sales, become involved in subsidizing non-profit housing associations with land grants. There was no parallel in the early twentieth century United States to the German social insurance system, so there was also no substantial pool of this kind from which funds could have been drawn for non-profit purposes to subsidize low-income rental housing; this situation was decidedly different from the one in Germany.

Thus, due to the lack of support by reformers, labor, and the government, a wider non-profit housing movement did not arise in the United States, while saving institutions specializing in housing did. Once the SLAs were in place, they also constituted an essential element of a private real estate lobby that prevented the allotment of any government money to competing institutions and made life for American housing reformers more difficult [McDonnell Reference McDonnell1957].

Why mortgage banks emerged in Germany and failed in the United States

The origins of modern German mortgage banks, the oldest institution of the modern mortgage market, reach back to the aftermath of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), when Prussian rural noblemen were in urgent need of capital [Clark Reference Clark2007: 194ff]. Frederick the Great obliged local landholders to enter associations of debtors, the Landschaften, in which both the individual properties and all landholders in person mutually backed a mortgage bond that the individual debtor himself had to sell in order to receive capital. “In exchange for the compulsory membership, all members of the Landschaften held a ‘right to credit,’ so the Landschaft could not discriminate against individual estates. Therefore, a key to prevent adverse selection was the determination of the credit limit and the correct assessment of the estate to guarantee collateral”; the assessors were even personally liable for losses due to assessments that were too generous [Wandschneider Reference Wandschneider2013: 11]. These conservative lending standards and trust in the monitoring of the local landholders enabled the holders of larger estates to enter into considerable mortgage debt, whereas small landowners were usually discriminated against in these Landschaften. It also meant the creation of an organized credit system in times when personal loans were still the most common form of credit, and it established a special circuit of finance for largely agricultural purposes. The Landschaften maintained roughly 20 percent of the mortgage market, predominantly in rural areas, and served as a model for Scandinavian mortgage banks and the French 1852 Crédit Foncier, which in turn became the model for the German mortgage stock banks: private banks issuing first mortgages to individuals that were held on their books and financed through the sale of bonds (Pfandbriefe) of matching duration [Schönmann Reference Schönmann1993: 826ff].

Mortgage banks were not permitted prior to the 1850s because the Prussian state feared another strong rival for its state credit next to the growing railway and industrial bonds [Redenius Reference Redenius2009: 73]. Most of the mortgage banks were then founded between 1862 and 1872 as private stock companies to finance the expanding construction in urban areas. In 1872, mainly agricultural forces successfully pressured the government to harmonize the different mortgage laws and allow for interstate credit flows in Germany [Eberstadt 1920: 387]. “Whereas in 1865 the volume of private mortgage bank mortgages amounted to the modest sum of 66 million marks, with Landschaften reaching 470 million, in 1900 it had increased to 6.9 billion, exceeding the Landschaften (2.2 billion) threefold” [Redenius Reference Redenius2009: 76, transl. by author]. Prussian ordinances regarding mortgage banks prescribed highly conservative lending, which thus strengthened banks from more liberal southern states. With the advent of troubled banks and market transparency problems, the government then enacted the 1899 federal law that legally established mortgage banks as the only issuer of Pfandbriefe (only abolished in 2005); their practice of lending at a maximum of 60 percent ltv underpinned their reputation as the provider of long-term investments that were as stable as government bonds [Schmidt 1993: 1026ff]. Since Pfandbriefe were traded on German stock exchanges, mortgage banks did not need to be situated in the lending region nor issue Pfandbriefe there. Indeed, the expansion of Berlin and other Prussian cities was largely made possible at first by non-Prussian banks [Eberstadt 1901: 140].

The roughly 40 private mortgage banks grew to be the biggest financer of private urban construction in Imperial Germany, with 95 percent of their mortgages being made in cities. Undoubtedly, the mere economics of more expensive urban land and the corresponding demand of clients for apartment-building mortgages shaped their business, but some characteristics of their own made them a functional complement to private apartment-building construction. First, whereas mortgage banks issued bonds in relatively small shares to attract greater demand among institutional investors and the wealthy bourgeoisie, they preferred to issue mortgages of higher nominal values. Contrary to the other major source of mortgage finance in Imperial Germany, namely the local savings banks (Sparkassen), mortgage banks could not count on a diversified network of branches to serve small customers with amortizing mortgages [Eberstadt 1920: 424f]. The administrative costs for smaller mortgages and regular amortization payments (and non-payment sanctions) would have been much higher. Moreover, the relatively frequent trade in land or apartment buildings made non-amortizing mortgages more attractive as they could be passed onto the buyer more easily (ibid. 402]. Second, contrary to cooperative banks or Sparkassen, mortgage banks were not tied to investments in certain regions. Their lack of a branch system implied less knowledge of local conditions, and it is evident in their evaluation guidelines that they even mistrusted local evaluators, fearing they were possibly corrupt [Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen1894b]. Instead, mortgage banks had to rely on more standardized ratings based on the most standardized product in urban construction—the apartment building—while otherwise following conservative lending standards [Faller Reference Faller2001]. The stereotyped rental building, much criticized from architectural and city-planning points of view, served the purposes of the banks much better. Third, since mortgage banks had to pay continued interest on their bonds––as codified in the mortgage banking law––they were strongly inclined to issue loans on income-generating objects, the best of which were apartment buildings with their continuously flowing rent payments [Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen1894a: 233, vdh 1999: 39]. The granting of mortgages for single-family homes was an exception to this practice that was only found in the German southwest [Fuchs Reference Fuchs1929: 47]. The mortgage banks thus became major players in the organized mortgage market that were at least as important in Germany as the SLAs were in the United States, but they financed apartment buildings, not single-family houses.

Mortgage banks could not have flourished, of course, without the demand created by long-term bond investors or without the existence of a landlord class willing to own and manage real estate. This class was mainly made up of many small owners, often from the petty bourgeoisie, who invested surplus profits from small companies in city property. Possibly, the relative insignificance of stock investments for the German middle classes was a reason why these classes invested in mortgage bonds and real estate. Highly organized already during the Imperial period, this landlord class became an important pillar of the housing market and a strong interest group for liberal rent legislation. They were a part of the old middle classes, the Mittelstand, which conservative political groups courted from the 1890s onwards [Unterstell Reference Unterstell1989]. Thus, private landlords could count on fewer post-wwi rent restrictions than in neighboring countries [Führer 1999] and later became addressees of tax subsidies and depreciation allowances [Voigtländer Reference Voigtländer2009]. At the same time, the 1920s witnessed the first attempts at national tenancy legislation which—though opposed by landlords—also made renting permanently attractive for tenants. Both the political support for private landlords and the national tenancy legislation distinguish Germany from the United States and guaranteed credit demand for mortgage banks.

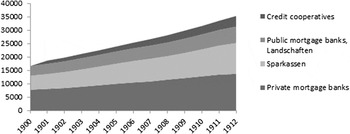

Figure 1 Pre-wwi mortgage market volumes in million marks

Source: [DeutscheBundesbank 1976] via Gesis; volume of Pfandbriefe for the public mortgage banks; Sparkassen-mortgages calculated as Prussian percentage of mortgages as part of German Sparkassen assets; all credit volume for the credit cooperatives.

In the US, on the contrary, bond-issuing mortgage banks preferring income-generating rental objects did not succeed. “Mortgage securitization appeared in six different forms between 1870 and 1940, and each time the market for mortgage-backed securities grew rapidly for a few short years and then collapsed” for largely two reasons [Snowden Reference Snowden1995b: 262]: only unstable private mortgage banks without a state-supported structure arose, and financial regulation preventing defaults and over-lending crises remained nonexistent [ibid. 275]. “The major problem was the informational asymmetry between bondholders and lenders. Many mortgage banks exploited their informational advantage by placing high-risk, high-interest loans behind the bonds” [Lea Reference Lea1996: 158]. When a capital market for secondary mortgages was eventually created in the 1930s, it was built on the existing system of mortgage-lending, which was dominated by the mortgages for single-family houses awarded by deposit institutions such as the SLAs.

Most of the attempts prior to the 1930s concerned farm mortgages in times of new settlement in the 1880s and of production extensions such as wwi or farmers’ indebtedness problems in the 1920s [Snowden Reference Snowden2007]. The first national securitization system, instituted by the Farm Loan Act of 1916, deserves mention as it anticipated the latter urban mortgage securitization for the case of farm mortgages [Prasad Reference Prasad2012: 199]. The Act created a Federal Reserve of land banks that relieved commercial banks of problematic farm mortgages and guaranteed new loans corresponding to standardization requirements. When the realtors and the SLAs lobbied for a national mortgage securitization system after wwi for the first time, the Farm Loan Act served as their guiding example. A second pillar of the Act allowed voluntary local credit cooperatives that would mutually guarantee their issued mortgage bonds, a system reminiscent of the German Landschaften but adapted to the American context. The century-old institutional heritage of modern German mortgage banks like the eighteenth century Landschaften, however, was lacking in post-colonial America. Imposed as a compulsory credit cooperative from above, often on noble landlords who felt strong ties to their localities, the Landschaften model was neither compatible with the transatlantic reservations about strong governmental measures nor with the nonexistence of a locally bound elite in a young society of small settlers [Frederiksen Reference Frederiksen1894b: 60]. Thus, these cooperative banks for agricultural purposes could not serve as models, as they had in Germany, for the development of mortgage banks focused on urban real estate in the nineteenth century. More generally, the development of modern urban mortgage institutions seems to hinge upon early rural mortgage models that evolved into a centralized, bond-issuing model in urban Germany and a secondary mortgage market model in urban America that was created, standardized and guaranteed by the government.Footnote 4

The last American mortgage-bond type to appear prior to the Great Depression emerged in the 1920s and fueled the overproduction of apartment houses that ultimately led to the demise of this financing tool [Radford Reference Radford1996: 13f]. “The timing of the rental housing boom [1926-1929] was greatly influenced by the growing popularity of mortgage bonds in the financing of rental housing” [Grebler Reference Grebler1950: 132]. During that period, this new bond-based mode of financing led to the highest percentages of multifamily units in new construction in American building history, equaling up to 54 percent of all units. Usually the buildings were larger apartment projects, often in New York City [Baar 1989: 111]. In peak times, mortgage bonds reached a volume of several billion dollars, of which roughly half went into apartments and apartment hotels, while the remainder fueled business construction [Goetzmann and Newman Reference Goetzmann and Newman2010, White Reference White2009]. Historically, the origins of bond-issuing institutions, which mediated between the building companies in larger cities and private investors, lay in the 1904 legalization by New York State of the private mortgage insurance business since the elimination of the risk of default is a precondition of successful bond securitization. However, lax supervision, over-lending, and the oversaturation of the apartment market then led to the practical disappearance of this industry after the 1929 Wall Street crash.Footnote 5Figure 2 shows the rise and fall of the bond curve and the general rise to dominance of the SLAs and thrift institutions.

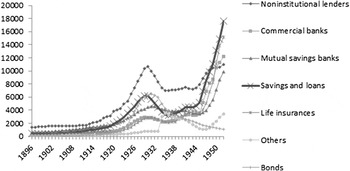

Figure 2 Residential non-farm outstanding mortgages in million dollars

Source: [Snowden Reference Snowden2006a].

The general absence of mortgage bonds in the United States prior to government intervention also reflects the prevailing regionalization of mortgage markets and the low degree of interregional lending even for non-securitized mortgages. Savings banks and the SLAs, which were the traditional urban mortgage lenders along with personal lending networks, were restricted by law to lend within their own region or state. Ethnic SLAs, in turn, focused on their respective neighborhoods; their concentration of risk was compensated by a precise knowledge of local conditions and of lenders, and by better monitoring mechanisms [Snowden Reference Snowden1995a: 218]. The one exception to this rule of localism in mortgage lending was that of life insurance companies, which successfully managed to monitor local loan agents and enforce defaulting mortgages quickly. Life insurance companies held 60 percent of their assets in mortgages, sometimes up to 10 percent directly in real estate, but gradually reduced their share to below 15 percent in the twentieth century in favor of alternative investments in railroad and government bonds [Saulnier Reference Saulnier1950: 12]. While they held a high number of home mortgages (up to 90 percent in the early twentieth century), the volume of their investments in dollars was very directed towards income-producing residential and commercial mortgages (45 percent in 1946) [ibid. 49], known for long-term amortizing loans with high ltv ratios.

Thus, the lack of sufficient government regulation, the absence of a feudal mortgage-bank tradition, and the dominance of local deposit-banking prevented the rise of an institution similar to the German mortgage banks.

The dependence of governmental housing policy on existing institutions

So far I have described how the basic housing institutions in Germany and the United States emerged in the nineteenth century. Although they undoubtedly received legal and sometimes even direct or indirect financial aid from governments, it would be misleading to talk of any government design behind the different institutional worlds that developed. German mortgage banks grew out of an initial desire to enhance agricultural credit. German cooperatives profited rather collaterally from the social insurance funds, which had obviously been set up for purposes other than housing. The first contact American SLAs had with the federal government was the 1893 survey that documented their decade-long emergence and growth.

The history of the origins of American and German housing policies has already been written elsewhere [Schwartz Reference Schwartz2014a, Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1991]. What is of particular interest here is to show that the principal government housing policies were determined by the pre-existing institutional world once the postwar or Depression housing crises set in. I will therefore describe how the main government housing policy programs directly addressed features of those already existing institutions while ignoring others.

In the American case, the 1930s saw the development of three major housing policy institutions: federal insurance for standardized mortgages, public housing, and a secondary mortgage market. The immediate reaction to the foreclosure problems after 1929 was the establishment of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (holc), which bought problematic mortgages from lenders, amongst them a considerable number from SLAs [Harriss 1951: 35]. The SLAs successfully lobbied in favor of supporting New Deal legislation and against any additional mortgage offers from the government that would crowd out private mortgages [Mason Reference Mason2004: 96]. Both the publicly organized insurance of private mortgages through the Federal Housing Association of 1934 and the publicly organized resale of privately issued mortgages on a secondary market can be understood as merely complementary institutions that helped make the SLAs the financers of American postwar suburbanization. Another innovation financed generously by the federal government that made private mortgage products more attractive was the new opportunity to deduct mortgage costs from personal income taxes.

At the same time, American housing reformers attempted unsuccessfully to copy the European subsidy scheme for non-profit associations. Under the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Public Works Administration (pwa) created a housing division that adopted a limited-dividend subsidy program originating in President Hoover’s Reconstruction Finance Corporation (rfc). In 1932, the rfc had looked in vain for housing associations worthy of its subsidies and had found only one such association in New York. The subsequent pwa program suffered a similar fate when the Carl Mackley Homes of the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers became its only completed housing project [Radford Reference Radford1996: 111]. The lack of adequate housing associations qualified to be the beneficiaries of subsidies outside of New York brought Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior, to rely on direct governmental top-down housing developments. Thus, the public housing administration had to build the first public housing units itself and had to initiate a new infrastructure of local housing authorities. Without an existing lobby on behalf of the housing movement and with high capital subsidy costs, the building of public housing became an easy target of cutbacks from the 1950s onwards.

In the German case, the federal government began to intervene in the non-profit housing sector in the 1920s and became much more heavily involved in the post-wwii era, when the first Bausparkassen subsidies were also initiated. For the private rental apartments traditionally financed by mortgage banks, it became important to develop rent and tenancy regulations that simultaneously protected tenants and ensured financial profits. The Weimar Republic saw the first housing-specific tax legislation and the first non-profit housing credit programs. Union-associated cooperatives and building construction trades in particular became the main recipients of the public housing subsidies, which reached their peak between 1924 and 1931. Thanks to government subsidies, the union-owned Neue Heimat became the largest real estate company in Germany until the 1980s.

Bausparkassen savers received government subsidies in the course of the general attempt to mobilize more private capital in the 1950s by promoting savings earmarked for housing construction through bonuses and income deductions on savings. The 1952 Wohnungsbauprämienrecht (housing subsidy legislation) initially provided saving bonuses for all kinds of savings related to housing investments, but it seemed tailored to the existing housing finance institutions [Pergande and Pergande Reference Pergande and Pergande1973: 183]. In its general pursuit to enable workers accumulate wealth, the government subsidized Bausparkassen savings. The idea was to encourage lower- and medium-income employees to accumulate savings earmarked for purchasing housing, and to have their employers contribute to workers’ wealth formation by matching those funds [Kohlhase Reference Kohlhase2011: 41]. In 1969, lower-income groups received additional bonuses, but the state subsidies were steadily reduced as of 1974 [ibid. 127f].

When it came to the financial sector, German housing policy was concerned with the incentive to save. Otherwise, the policy aims were to encourage the construction of rental housing units in the social and private sector. In the United States, however, most of the governmental housing budget was directed at supporting housing finance institutions. These differences in housing policy regimes are a direct reflection of the housing institutions predating the first housing laws in both countries.

Conclusion

I started out by noting that Germany and the United States fall into opposing housing regime typologies in many respects. Particularly salient are the different percentages of homeowners and private and public tenants in their respective populations. In this article, I introduced a new explanatory factor to account for these differences, namely the history of housing finance institutions. More specifically, I addressed the question of why the United States developed an sla-dominated system, while mortgage banks and the non-profit association circuit were more important in Germany. As housing form and tenure follow finance, these institutional differences were reflected in the housing stocks that were built in the countries during crucial phases of their urbanization. Housing stock in turn strongly correlates with tenure form in the two countries, i.e. single-family houses are dominantly owner-occupied, and apartments are rented. While the variations today between different housing finance systems have already been noted [Boléat Reference Boléat1985], this article makes a new contribution by describing these systems’ origins and their historical impact on housing regime differences.

To sum up: SLAs tended to develop in non-banked areas and reflected the experience of pioneering American settlers, while the rise of a non-profit housing movement similar to the one in Germany was preempted by a lack of support from the labor movement, reformers, and the government as well as the absence of any kind of funding that might have existed had there been a social security system in the United States in the nineteenth century. Because the tradition of feudal mortgage banks was utterly lacking in the United States and the lending behavior of temporarily arising mortgage banks was not regulated, bond-financed mortgage banks did not emerge in the United States. In Germany, however, SLAs were preempted by an existing banking network and the competing non-profit housing associations, which were supported by active municipalities, reformers, and eventually the government. Government housing policies, in turn, were built on the existing institutions. The holc rescue bank, mortgage insurance, and the secondary mortgage market system mainly for SLAs in the United States were paralleled by a residual government-controlled public housing sector, since there was no non-profit housing movement. The German government subsidized non-profit housing and focused its homeowner subsidies on the ex-ante savings, which were mostly used by the members of Bausparkassen. Thus, US institutions gave the American housing policy a finance bias, while German institutions gave that country’s housing policy a construction-subsidy bias.

The historic sequence of nineteenth century developments featuring limited-profit housing associations, rental-housing mortgage banks, and twentieth century SLAs is paralleled by Austria, Switzerland, and France [Bouveret 1977], which copied the German Bausparkassen model in the 1930s [Deutsch and Tomann Reference Deutsch and Tomann1995], albeit to a much lesser degree in capital-rich, low-interest-rate Switzerland [SBG 1979: 30]. One of the persisting features of this Continental sla model is the relatively high percentage of equity that households save prior to entering homeownership at an above-average age. Interestingly, mortgage banks based on the sale of covered bonds have never emerged in Belgium, where the predominant type of dwelling is small, owner-occupied houses [Doling and Elsinga Reference Doling and Elsinga2013: 33].

At the same time, SLAs spread through the English-speaking world. The first international congress of building societies that included the promotion of homeownership in their constitutions was almost exclusively frequented by members of English-speaking countries [Ewalt Reference Ewalt1982, Price Reference Price1958: 454ff]. In most English-speaking countries, these institutions became the main financers of homeownership expansion [Donnison and Ungerson Reference Donnison and Ungerson1982: 212]—making up 35 percent of the twentieth century Australian market, for instance [Kemeny Reference Kemeny1983: 17f]. An independent tradition of non-profit housing cooperatives has yet to develop there [Kemeny Reference Kemeny1981: 10].

This article stresses the importance of reconsidering the differences in financial systems between countries—which have been much discussed with regard to capital investments in companies—from a new housing-finance perspective. If Germany’s financial system is to be called bank-based and that of the United States market-based for company finance [Zysman Reference Zysman1983], it is interesting to note that the housing finance constellation for the two countries is reversed: German mortgage banks channeled money from the anonymous capital market into the housing sector, whereas local deposit banks were the dominant actors in the United States. This article emphasizes how these differing constellations significantly impacted types of housing, forms of tenure and eventually the shape of cities. Given the importance of the housing sector in an economy with regard to savings, credit, and investment, future research should focus on other consequences of the differences between historical housing finance institutions in countries. Can the differences in these systems, for instance, explain cross-national differences in saving rates? How much do these systems contribute to the stability of countries in times of financial crisis? To what extent do these institutions channel capital into the housing sector, when compared with the sectors of industry, services or the state? Further inquiry into the composition and organization of historic mortgage markets of more countries could also promise a more encompassing typology along the lines proposed here.