Disaster is defined as a nature, technology, or human-induced event that causes physical, economic, and social losses in society, and stops or interrupts normal life and human activities. 1 Disasters emerge as an important public health problem in terms of high morbidity and mortality rates and the economic losses they cause. Reference Taşkıran and Baykal2 The increase in disasters around the world seriously affects human health, environmental health, and the economy. In the past decade, more than 2.6 billion people in the world have been affected by natural events such as earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, hurricanes, heat waves, floods, or severe cold weather. 3

Turkey is a country that frequently encounters natural disasters due to its tectonic, seismic, topographic, and climatic structure. Disasters seen in Turkey include floods, floods, avalanches, landslides, fires, but most importantly earthquakes. Turkey ranks third in the world in terms of human loss in earthquakes and eighth in terms of the number of people affected. On average, at least 1 earthquake with a magnitude between 5 and 6 occurs every year. 4,5 Two major earthquakes of magnitude 7.7 and 7.6 occurred in our country on June 2, 2023, centered in Kahramanmaraş, and nearly 60,000 people lost their lives, and 107,000 people were injured. 4

Being prepared for disaster management has an important place in reducing the harmful effects of emergencies and disasters. Reference Baack and Alfred6 Nurses are the health professionals who are most responsible for reducing risks in the environment and protecting health during disasters. In this context, nurses’ knowledge about disasters, their preparedness for disasters, and their capacity to respond quickly play an important role in the management of disasters. Reference Veenema, Griffin and Gable7 Nurses can engage in a wide range of nursing activities such as environmental assessment, triage, decontamination, patient care, chronic disease management, treatment, care of the deceased, and rehabilitation in disasters. These activities also require nurses to respond to disasters under difficult conditions and with limited resources, to adapt to the process, and to communicate effectively with other health-care providers. Reference Taşkıran and Baykal2

At the same time, it is emphasized that preparing nurses more effectively for disasters is 1 of the mandatory issues of the 21st century. Reference Kamanyire, Wesonga and Achora8 Therefore, it is very important for nursing students to learn the knowledge and skills necessary to be ready for and respond to disaster situations throughout their education process. Reference Bülbül9 Studies have determined that most nurses have low levels of knowledge and readiness to respond to disasters. Reference Loke, Guo and Molassiotis10 Additionally, studies on disaster management in nurses/nursing students have also shown that nurses do not have the relevant competencies to manage disasters effectively. Reference Bülbül9,Reference Usher, Redman-MacLaren and Mills11–Reference Avcı, Kaplan and Ortabağ14 Studies conducted in Japan, Reference Öztekin, Larson and Akahoshi15 the Philippines, Reference Labrague, Yboa and McEnroe-Petitte16 and the United States Reference Baack and Alfred6 showed that nurses were not competent and self-confident in responding to disaster events, and that they did not plan their workplace emergency or disaster plans. They stated that they did not think they could implement it. Additionally, nurses in some developed and developing countries have not been adequately prepared for disaster management. Reference Usher, Redman-MacLaren and Mills11

Contrary to the research results, nurses and nursing students are expected to have high disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness. Nurses’ skills and readiness to respond to any disaster event are largely related to their self-efficacy. Studies have determined that disaster-related self-efficacy and previous experience in disaster management affect disaster preparedness in nurses/nursing students. Reference Mousavi, Majidi and Shabahang17,Reference Wutjatmiko, Zuhrivah and Fathoni18

It is important to increase nursing students’ disaster preparedness and disaster response self-efficacy to avoid damages that may occur because of a disaster. In short, it is important to increase the disaster self-efficacy levels of nursing students to ensure their preparedness for disaster. However, no study examining the relationship between these 2 concepts has been found in our country. However, Turkey is a risky country in terms of disasters. For this reason, it is necessary to first reveal the relationship between these concepts to plan appropriate interventions to ensure that future nurses are prepared for disasters. Therefore, this study aimed to reveal the relationship between nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy and their perceptions of disaster preparedness. Determining nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy and preparedness perceptions is important in planning initiatives based on sustainable development goals.

Research Questions

-

1. What is the disaster response self-efficacy level of nursing students?

-

2. What is the perception of disaster preparedness level of nursing students?

-

3. Is there a relationship between nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy and their perceptions of disaster preparedness?

-

4. What are the predictors that affect perception of disaster preparedness in nursing students?

Methods

Study Design

This is a cross-sectional study.

Place and Time of Study

The research was conducted at a university in western Turkey between June 12, 2023, and October 27, 2023.

Study Setting and Sample

The population of the research consisted of 3rd and 4th grade students studying at a university’s Faculty of Health Sciences/Department of Nursing. Because students studying in this department take both Emergency Nursing and First Aid and Public Health Nursing courses until the 3rd grade, they have knowledge and awareness about disasters. For this reason, the population of the study consisted of 3rd and 4th grade nursing students (N = 315).

In the study, a 2-way hypothesis was established to examine the relationship between nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness, and the number of samples was calculated using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 program. The correlation value was taken as 0.21 and the required number of samples was calculated as at least 289 with a 5% margin of error for the correlation analysis (α = 0.05, H0 correlation value 0 and 95% power (1-β = 0.95). Missing data were considered during the research process. Ten percent more individuals were included in the study. Initially, 310 students participated in the study, 8 students were excluded because they had incomplete answers in the data collection forms, and the study was completed with a total of 302 students. The inclusion criteria for the study were: (1) being a student in the nursing department, (2) 3rd and 4th grades (must be at least a 3rd grade student), and (3) be over 18 y of age. Exclusion criteria; students who have started the 3rd grade with transfer from other departments and have not taken Emergency Nursing and First Aid courses (Departments such as Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Elderly Care, etc.). Students who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study formed the sample of the study.

Instruments

A personal and disaster-related information form, Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale, and Nurses’ Disaster Preparedness Perception Scale were used as data collection tools.

Personal and Disaster-Related Information Form

This form was prepared by researchers in line with the literature. Reference Kamanyire, Wesonga and Achora8,Reference Bülbül9,Reference Özcan and Erol19–Reference Ciris Yildiz and Yildirim22 This form contains questions about individuals’ socio-demographic characteristics and their knowledge and attitudes toward the disaster.

Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale (DRSES)

This scale was developed by Li et al. in 2017. Reference Li, Bi and Zhong23 The Turkish validity and reliability of the scale was conducted by Toraman and Korkmaz in 2023. Reference Toraman and Korkmaz24 The scale is a 5-point Likert type and consists of a total of 19 items and 3 sub-dimensions (Search and rescue and psychological assessment self-efficacy, Disaster assessment self-efficacy, Adaptation self-efficacy). The scale is answered as “I don’t have any confidence in myself (1 point), I don’t have confidence in myself (2 points), I have very little confidence in myself (3 points), I have confidence in myself (4 points), and I have great confidence in myself (5 points).” The scale score is calculated by summing the answers to the questions. A high score from the scale indicates high disaster response self-efficacy. The minimum score from the scale is 19 and the maximum score is 95. In the Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was found to be 0.94 and test-retest reliability was 0.95. Goodness-of-fit indexes of the scale are x2/df 2.540; RMSEA: 0.067; GFI: 0.93, CFI = 0.93, IFI = 0.92, NFI: 0.95, TLI: 0.94.

Disaster Preparedness Perception Scale (DPPS)

It is a scale developed in Turkish by Özcan and Erol in 2013 to measure how prepared nurses feel against disaster. The scale consists of 20 items and 3 sub-dimensions. Sub-dimensions; Preparation phase (questions 1-6), Intervention phase (questions 7-15), After disaster phase (questions 16-20). Scale items are 5-point Likert type and are scored as (1-Strongly Disagree, 2-Disagree, 3-Partly Agree, 4-Agree, 5-Strongly Agree). As the score obtained from the scale increases, the perception of disaster preparedness increases. The cutoff points of the scale are determined by dividing the total of the scale and subscale scores by 5. For the subscale and total scale, the score is 1.00-1.79 as very low, 1.80-2.59 as low, 2.60-3.39 as moderate, and 3.40-4.19 as high. The content validity of the scale was found to be 92%, the Cronbach Alpha value was 0.90, and the test-retest reliability coefficient was 0.98. Reference Özcan and Erol19

Data Collection Process

The data of the research were collected in the classroom environment using the face-to-face data collection method. Data collection took an average of 30 min. The entire process and dates of the study are as follows: Identifying the problem (February-March 2023), Literature review (March-April 2023), Creating the research question (April 2023), Determining the research and analysis methods (April-May 2023), Data collection and analysis (12.06.2023-27.10.2023).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 22.0. Descriptive statistics including mean, standard deviation, and percentage were used to express data about descriptive characteristics, DRSES and DPPS. Because data collected with the DRSES and DPPS had a normal distribution (Skewness/Kurtosis value for Self-Efficacy: 0.542/-0.700; Skewness/Kurtosis value for Preparedness: 0.432/-0.224), parametric tests were used for analysis of the data. Independent samples t-test was used to determine the differences in the mean scores on the DRSES and DPPS in terms of sociodemographic features between 2 groups and Bonferroni corrected 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the differences among 3 or more groups. The relation between the mean score on the DRSES and the mean score on the DPPS was examined by using Pearson correlation analysis. The factors affecting disaster preparedness was determined with a multiple linear regression analysis. P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Disaster Related Characteristics of the Nursing Students

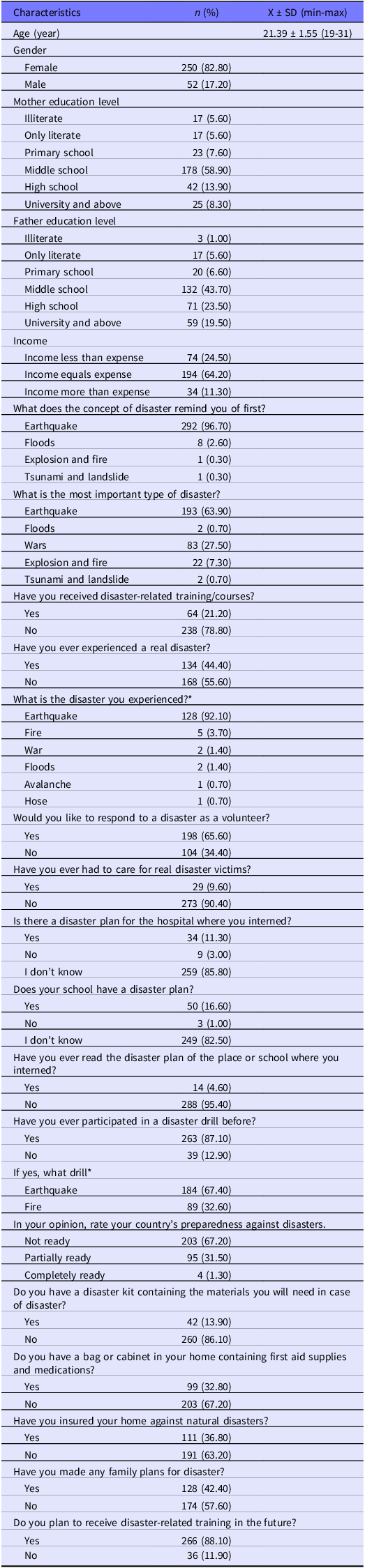

The mean age of nursing students is 21.39 ± 1.55. In the study, 82.8% of the nursing students are female. The concept of disaster reminds students of earthquakes the most (96.7%). The type of disaster that students find most important is earthquake (63.9%) and war (27.5%). Only 21.2% of the students received disaster-related training. A total of 44.4% of the students reported that they had experienced a disaster, and 92.1% of them had experienced an earthquake. Most of the students reported that they wanted to intervene in the disaster (65.6%). Most of the students have participated in disaster drills before (87.1%), 67.4% of which were earthquake drills. While only 13.9% of the students have a disaster kit, 32.8% have a first aid kit (Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and disaster related characteristics of the nursing students (n = 302)

Abbreviations: X, mean; SD, standard deviation; min, minimum; max, maximum.

* Participants marked more than 1 option.

DRSES and DPPS Score Means of Nursing Students

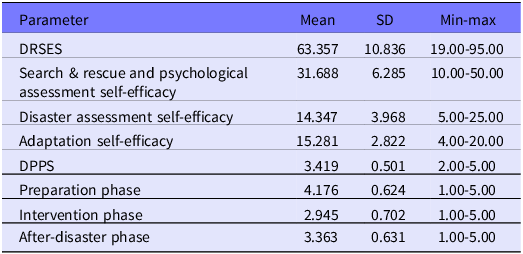

In this study, the DRSES score of nursing students is 63.35 ± 10.83 (moderate level), the search and rescue and psychological assessment self-efficacy subscale score is 31.68 ± 6.28, the disaster assessment self-efficacy subscale score is 14.34 ± 3.96, and the adaptation self-efficacy subscale score is 15.28 ± 2.82. Nursing students’ DPPS score is 3.41 ± 0.50 (high level), preparation phase subdimension score is 4.17 ± 0.62 (high level), intervention phase subdimension mean score is 2.94 ± 0.70 (moderate level), after disaster phase subdimension score is 3.36 ± 0.631. It was found to be 0.63 (moderate level) (Table 2).

Table 2. Scale score averages of nursing students

Abbreviations: DPPS, Disaster Preparedness Perception Scale; DRSES, Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale; min, minimum; max, maximum; SD, standard deviation; X, mean.

Comparison of Nursing Students’ Scores From DRSES and DPPS in Terms of Demographic and Disaster Related Characteristics

The mean scores of male students in DRSES (66.94 ± 9.77), search and rescue, and psychological assessment self-efficacy (34.42 ± 5.13) and disaster assessment self-efficacy (15.69 ± 2.84) were found to be significantly higher (P < 0.05). Only the DPPS (3.55 ± 0.59) and disaster assessment self-efficacy (15.64 ± 4.63) mean scores of the students who had previously received disaster-oriented training were found to be significantly higher than those who had not received disaster-oriented training (P < 0.05). While the mean scores of DRSES (65.34 ± 9.92), search and rescue, and psychological evaluation competency (32.79 ± 5.93), disaster assessment self-efficacy (15.17 ± 3.79) of students with previous disaster experience are significantly higher than those of students without disaster experience. DRSES (69.07 ± 8.98) and search and rescue and psychological assessment self-efficacy (35.35 ± 4.21) scale scores of the students who read the disaster plan of the place or school where they did their internship were found to be significantly higher than the students who did not read the disaster plan before. DRSES and DPPS scores of students who have a disaster kit containing the materials they will need in case of a disaster are higher than students who do not have a disaster kit. The DPPS (3.53 ± 0.52), DRSES (65.28 ± 11.47), disaster assessment self-efficacy (14.49 ± 4.30), and adaptation self-efficacy (16.04 ± 2.76) mean scores of the students who made family planning for a disaster were found to be significantly higher than the students who did not make family planning (Table 3).

Table 3. Comparison of nursing students’ scores from DRSES and DPPS in terms of demographic and disaster related characteristics

Note: One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni, t = independent sample t-test <0.05.

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DPPS, Disaster Preparedness Perception Scale; DRSES, Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale.

Relationship Between DRSES and DPPS Mean Scores in Nursing Students

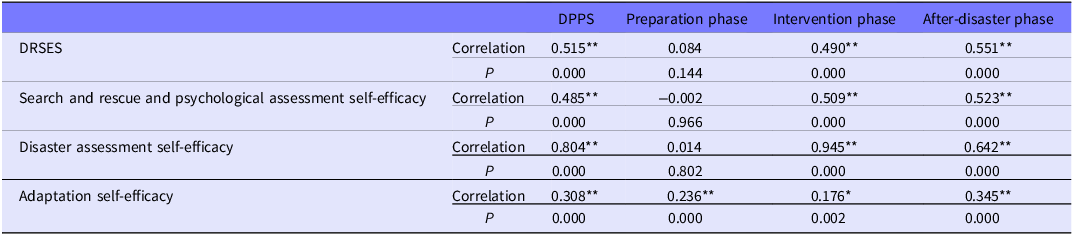

A positive and moderate correlation was found between the DRSES scale score and the DPPS scale score of nursing students (r = 0.515; P = 0.000). A positive and moderately significant correlation was found between nursing students’ DRSES scale score and the intervention phase (r = 0.490; P = 0.000) and after-disaster phase mean score (r = 0.551; P = 0.000) (Table 4).

Table 4. Relationship between DRSES and DPPS mean scores in nursing students

Abbreviations: DPPS, Disaster Preparedness Perception Scale; DRSES, Disaster Response Self-Efficacy Scale.

* = p < 0.01, ** = p < 0.05.

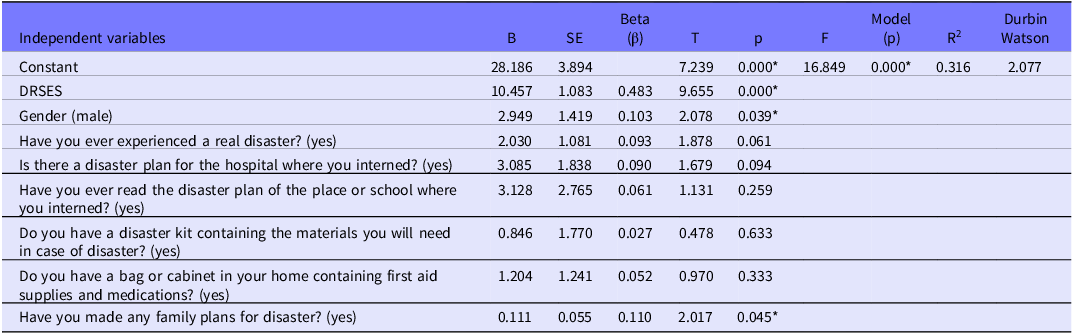

Predictors Affecting Disaster Preparedness in Nursing Students

Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to determine the predictors affecting the disaster preparedness of nursing students. According to the analysis results, increasing disaster response self-efficacy of nursing students (β = 0.483), being male (β = 0.103), and making a family disaster plan (β = 0.111) were determined as predictors that increased disaster preparedness (Table 5).

Table 5. Predictors affecting disaster preparedness in nursing students

Abbreviations: SE, standard error of coefficient; β, standardized regression coefficient; R2, proportion of variation in dependent variable explained by regression model; p, the level of statistical significance, *P < 0.05.

Discussion

In the study, the disaster response self-efficacy of the nursing students was found to be at a moderate level and their disaster preparedness was found to be at a high level. There is a positive relationship between nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness. In addition, high disaster response self-efficacy is among the predictors affecting nursing students’ disaster preparedness. Previous studies have determined that most nurses have low knowledge and readiness to respond to disasters. Reference Loke, Guo and Molassiotis10,Reference Avcı, Kaplan and Ortabağ14 Additionally, studies on disaster management in nurses/nursing students have also shown that nurses do not have the relevant competencies to effectively manage disasters. Reference Bülbül9,Reference Usher, Redman-MacLaren and Mills11–Reference Avcı, Kaplan and Ortabağ14 Studies conducted in Japan, Reference Öztekin, Larson and Akahoshi15 the Philippines, Reference Labrague, Yboa and McEnroe-Petitte16 and the United States Reference Baack and Alfred6 showed that nurses were not competent and self-confident in responding to disaster events, and that they did not plan their workplace emergency or disaster plans. They stated that they did not think they could implement it. Additionally, nurses in some developed and developing countries have not been adequately prepared for disaster management. Reference Usher, Redman-MacLaren and Mills11

In our study, nursing students reported that they were willing to receive education about disasters to prepare for disaster management. This finding is consistent with Al Khalaileh et al. (2012), which is similar to a previous study. Nursing students were found to express a strong need for disaster nursing content. Reference Al Khalaileh, Bond and Alasad25

Attendance in disaster-related training or courses has been established as an important strategy to improve nurses’ disaster readiness and competencies. Previous studies have identified higher levels of competence and preparedness for disaster events among nurses who had undertaken training and courses related to disaster. Surprisingly, in our study, more than half of the nursing students reported not having attended any disaster-related courses or training, which aligns with earlier studies. Reference Bülbül9,Reference Labrague, Kamanyire and Achora20,Reference Rizqillah and Suna26 The fact that there is no difference between the disaster response self-efficacy scores of students who received training and those who did not receive training may indicate that the training is not effective and sufficient in practice.

The concept of disaster reminds students mostly of earthquakes, and the type of disaster they find most important is earthquake. Most of the students stated that their disaster experience was an earthquake. The reason for this is that Turkey is an earthquake country and a major earthquake occurred on February 6, 2023. 4 It is an expected result that the disaster response self-efficacy, search and rescue, and psychological evaluation proficiency, and disaster evaluation proficiency mean scores of students with previous disaster experience will be higher than those without disaster experience. Labrague et al. (2021) found that the disaster response self-efficacy of nurses who had experienced disasters before was high. However, the fact that nursing students’ adaptation competence was not high in this study indicates that their self-efficacy will be low in case of a disaster, and they will not be able to cope with the disaster effectively.

The reason why there is no difference between the disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness of students who have participated in disaster drills and those who have not participated before indicates that the disaster drills are not functional and do not give effective results for the moment of disaster. Many studies have found that interactive, simulation-based, and learner-centered nursing education programs helped prepare health-care professionals and positively influenced their self-confidence, motivation, and disaster response attitudes. Reference Kose, Unver and Tastan27 In the experimental study conducted by Erkin et al. (2023) it was observed that the disaster nursing course positively improved nursing students’ disaster awareness, disaster preparedness, and disaster response self-efficacy perceptions. Reference Erkin, Konakçi and Arkan Üner28 Kamanyire et al. (2021) reported that it is mandatory for nursing students to be included in regular disaster drills and simulations to gain knowledge about institutional and personal disaster preparedness. Reference Kamanyire, Wesonga and Achora29

The number of students who have a disaster kit containing the materials they will need in case of a disaster and a cabinet/bag containing first aid materials and medicines at home is quite low. Also, in others study reported that most of participants did not have disaster kit preparation. Reference Unver, Basak and Tastan30 Students who have a disaster kit and first aid materials at home have a high level of disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness perception. This situation is associated with the fact that students already care about disasters and have high awareness about disasters. Again, although the number of students who plan for disaster within the family is low, these students have a high level of disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness perception. In a study conducted on nursing students, most of the students were unaware of the existence of an emergency plan and had not read the plan. Reference Koca and Arkan31 Additionally, among the predictors affecting the disaster preparedness of nursing students is any planning within the family for a disaster situation. It is also an important result that individuals who have high sensitivity and awareness about disasters in the family take such precautions against disasters.

The predictor that affects nursing students’ disaster preparedness is disaster response self-efficacy. This emphasizes the conclusion that self-efficacy is important in increasing nursing students’ disaster preparedness. It is important to increase the disaster response self-efficacy and disaster preparedness of nursing students to be prepared for disasters and intervene early in a society that lives in a region with a high risk of disasters, such as Turkey.

Although the disaster response self-efficacy of the nursing students participating in this study was found to be at a moderate level, programs to increase the perception of disaster preparedness are continuing or being implemented in Turkey. Currently, there are important plans and activities in Turkey regarding disaster management and the creation of applicable disaster management plans. Reference Erkin, Konakçi and Arkan Üner28 These plans must cover all health-care professionals. Additionally, AFAD organizes many Disaster Awareness and Preparedness Trainings. 32

Conclusions

As a result, although nursing students see themselves as moderate in disaster response, most of the students are willing to respond to disasters. Disaster self-efficacy is an important predictor of actual disaster response; thus, measures to increase disaster self-efficacy in nursing students are warranted. Nursing students’ disaster response self-efficacy affects their disaster preparedness perceptions. The results of this study highlight the importance of increasing the disaster response self-efficacy needed by nursing students to successfully assist patients in disaster situations. It can be used to evaluate the need for nursing departments in Turkey to include the disaster nursing course in the nursing curriculum. The increase in nursing students’ search and rescue and psychological assessments self-efficacy, disaster assessment competency and adaptation competency will increase students’ readiness and self-confidence in managing future disasters. Nursing education plays an important role in fostering disaster competence and confidence in responding to emergency and disastrous events by incorporating disaster-related content into the nursing curriculum using simulated disaster drills, first aid, and life support training.

Acknowledgments

I thank all the students who participated in this study and the university that gave the institution permission.

Author contributions

Eda Kılınç İşleyen: Conceptualization; data collecting; writing-original draft; analysis, review & editing. Zehra Demirkaya: Data collecting; conceptualization; investigation; writing.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the (TUBITAK 2209-A) under Grant (number 1919B012301666).

Competing interests

The author(s) declare none.

Ethical consideration

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Uşak University Non-Interventional Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Date: 08.06.2023/No: 136-136-13). Informed consent was obtained from all nursing students before starting the study. Besides, permission was received from the Faculty of Health Science where the study was conducted (Date and Number of Documents: 16.05.2023-E.142335). Permission was also obtained from the researchers developing the scales used by means of email.