As Indigenous communities undergo demographic changes, health conditions associated with old age (including dementia) are becoming more common and the health of older people is becoming a priority. Emergent literature points to Indigenous cultural practices and connection to place as having benefits in supporting health over the life course and into old age. Engagement and connectedness with kin, community, culture, and subsistence have been shown to be valuable contributors to well-being for Indigenous older adults (Lewis, Reference Lewis2010, Reference Lewis2014; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Additionally, wellness in late life has been linked to older peoples’ continued engagement in cultural roles related to teaching and the transmission of knowledge (Abonyi & Favel, Reference Abonyi and Favel2012; Baskin & Davey, Reference Baskin and Davey2015; Collings, Reference Collings2001; Lewis, Reference Lewis2011; Pace, Reference Pace2013), and humour as a cultural mechanism that bolsters resilience (Garrett, Garrett, Torres-Rivera, Wilbur, & Roberts-Wilbur, Reference Garrett, Garrett, Torres-Rivera, Wilbur and Roberts-Wilbur2005). Themes of empowerment and resilience in the literature are strongly related to a continued connection to place and culture.

In this article, I draw on the results of a Photovoice project about Southern Inuit experiences of aging and dementia, which was conducted in a small community in the NunatuKavut region of Labrador. Here, I explore the salience of place in Southern Inuit experiences of dementia and care, drawing attention to the relevance of the natural world in health promotion and care trajectories. My intent is to consider the role of culture and the natural environment in promoting behaviours that may contribute to healthy aging, be protective against cognitive decline, and support the maintenance of identity as people travel along their dementia journey. There is also a need to recognize the structural pressures that may be impacting the ability of older Indigenous people to age and be cared for “in place”.

It is evident from anecdotal evidence and the published literature that dementia has not, historically, been of significant concern in Indigenous communities (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002). However, demographic transitions, and the impacts of rapidly changing ways of life on older Indigenous peoples’ health, have contributed to an increase in the number of cases of dementia, which is now well established as a health concern in Indigenous populations (Jacklin, Walker, & Shawande, Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013; Radford et al., Reference Radford, Mack, Draper, Chalkley, Daylight and Cumming2015; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flicker, Lautenschlager, Almeida, Atkinson and Dwyer2008). Given the increasing burden, there remains a need to understand how best to support Indigenous people transitioning into dementia, and to ensure that culturally safe approaches to care are devised that reflect Indigenous peoples’ values related to personhood, quality of life, and care.

Indigenous populations experience a distinct constellation of elevated risk factors that increase their probability of developing dementia (Jacklin, Walker, & Shawande, Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). A “big change in culture”, for example, has been identified as having a significant bearing on the health of older Indigenous people, and is understood to play a role in shaping a person’s level of risk (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Lanting, Crossley, Morgan, & Cammer, Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011). Rapid changes to culture and ways of life have been posited to have implications in terms of diet and activity patterns, which play a role in determining a person’s health over the life course, as well as breaking down supportive social and caregiving structures (Hart-Wasekeesikaw, Reference Hart-Wasekeesikaw1996). Dementia risk in Indigenous communities relates to disparities in the social determinants of health, including poverty and low educational attainment, higher rates of associated diseases (hypertension, stroke, diabetes, cardiovascular disease) and higher rates of smoking and obesity, which may put Indigenous groups at elevated risk for developing dementia, particularly vascular dementias (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013; Loppie-Reading & Wein, Reference Loppie-Reading and Wein2009). High rates of head injury, childhood stress, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) relating to historical trauma may also be contributing factors (Henderson & Broe, Reference Henderson and Broe2010; Petrasek Macdonald, Barnes, & Middleton, Reference Petrasek Macdonald, Barnes and Middleton2015; Radford et al., Reference Radford, Delbaere, Draper, Mack, Daylight and Cumming2017). The effects of colonialism, including sedentarization, dispossession of land, and the long-term effects of the residential school system have additionally impacted Indigenous peoples’ health (Czyzewski, Reference Czyzewski2011).

The published literature demonstrates that for Indigenous people, dementia is often described as a natural part of the life cycle, with a loss of memory and ability, a return to “childlike” behaviours, or going “back to the baby stage” being perceived as an expected part of aging, and a natural stage in the life cycle (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Beyond the perception of memory loss and cognitive changes in old age as natural, it has been documented in some Indigenous settings that dementia may be perceived as sacred, representing a heightened ability to communicate with the creator and the spirit world (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002). However, in tension with the perception of dementia as “natural” is an increasing level of concern about the incidence of the condition in Indigenous communities, the capacity for adequate care provision, and the availability of culturally safe services and supports to ensure that people living with dementia can be appropriately cared for and enjoy a good quality of life (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Therefore, in contrast to nuanced cultural understandings of memory loss and other cognitive symptoms as a natural part of aging, a perception of dementia as worrisome, frightening, or a “terrible” disease, has also been documented. As Indigenous families negotiate the dementia journey, the realities of living with the condition are being acknowledged as a significant challenge at individual and community levels (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Although there is a growing literature representing late life and dementia among diverse Indigenous groups, representations of Inuit older adults’ experiences are scarce (Somogyi, Barker, MacLean, & Grischkan, Reference Somogyi, Barker, MacLean and Grischkan2015).

Cultural perceptions and explanatory models of dementia can influence how and when transitions into dementia are identified, as well as care trajectories, and approaches to caregiving (Carpentier, Bernard, Grenier, & Guberman, Reference Carpentier, Bernard, Grenier and Guberman2010; Kleinman, Reference Kleinman1978). The perception that dementia symptoms are a natural part of aging, for example, has been documented to have the effect of delaying diagnostic and care trajectories in some Indigenous communities (Jervis & Manson, Reference Jervis and Manson2002; Pace, Reference Pace2013). A delay in accessing biomedical care for dementia may reflect distrust of the Western medical system or a lack of accessible services related to dementia diagnosis and care, particularly in rural and remote communities (Jacklin, Pace, & Warry, Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; Jervis & Manson, Reference Jervis and Manson2002). A reluctance to leave one’s community to seek medical care may also shape help-seeking patterns, out of concern that people may not be allowed to return home if they leave. More broadly, cultural understandings of health and notions such as personhood may have bearing on how dementia – and people living with dementia – are recognized, understood, and cared for.

The notion of personhood has long been acknowledged in research and practice related to dementia (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997), and is a particularly salient point of reference when considering Indigenous experiences. Contrary to Western cultures and biomedicine, in which personhood is a status associated with individualism, in Indigenous cultures personhood tends to be relational and collective, with a person’s identity being inextricable from land, culture, family, and the natural world (Kirmayer, Simpson, & Cargo, Reference Kirmayer, Simpson and Cargo2003; Waid & Frazier, Reference Waid and Frazier2003). Among Inuit, for example, the concept of personhood has been shown to be ecocentric and cosmocentric, and health and wellness are achieved by seeking balance among the forces in the larger world (Kirmayer, Dandeneau, Marshall, Phillips, & Williamson, Reference Kirmayer, Dandeneau, Marshall, Phillips and Williamson2011).

For many Indigenous people, a strong relationship with the geophysical environment is a key determinant in their holistic conceptualization of health (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000; McMillan, Kampers, Traynor, & Dewing, Reference McMillan, Kampers, Traynor and Dewing2010). Among Southern Inuit, the maintenance of a constant, intimate relationship to the land is understood to be critical not only to health, but also to identity and indigeneity (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000). The land and sea, and the resources located within them, historically formed the basis of Southern Inuit life and health, including subsistence, travel, the economy, and leisure (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000). Key tenets of Southern Inuit beliefs about health include the principle of personal responsibility for individual and family well-being, and the maintenance of health through the fulfillment of relationship obligations to family, community, and the natural world (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000). Knowledge of how to live off the land and safely engage with the environment was crucial to ensure survival in this remote and often harsh environment and, beyond providing physical resources, the intimate relationship that Southern Inuit have with the land is a historical source of emotional support and well-being (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000). Although diverse factors have altered “traditional” ways of living in this region, many of the skills and values associated with the “Labrador life” remain central to contemporary Southern Inuit life.

The role of place and the environment in relation to health and aging are well documented in the literature, and topics such as “aging in place” and therapeutic landscapes have been a significant focus (Andrews, Reference Andrews2004; Conradson, Reference Conradson2005; Cutchin, Reference Cutchin2003; Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve, & Allen, Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012). The idea of therapeutic landscapes, for example, has considered the relationship between place and the prevention and treatment of illness as well as the enhancement of health (Conradson, Reference Conradson2005; Williams, Reference Williams2010). Significant lines of inquiry in relation to this topic include physical spaces associated with health (Gesler, Reference Gesler1996), formal sites of health care delivery (Andrews, Reference Andrews2004), and the meaning of environments to marginalized populations or special groups (Wilson, Reference Wilson2003). In mainstream literature, the idea of therapeutic landscapes has been theorized in relation to exceptional places or extraordinary events such as spas and shrines. However, discussions of the therapeutic value of landscape in an Indigenous context must consider Indigenous peoples’ everyday lives and their engagement with local environments (Wilson, Reference Wilson2003). In Indigenous settings, everyday interactions with surrounding landscapes are highly significant, and the landscape itself is considered to hold healing properties (Wilson, Reference Wilson2003). Continued interaction with spaces and places that are integral to subsistence and survival are inextricable from Indigenous peoples’ identity and livelihood, and thus play a role in defining personhood. As such, special considerations about the significance of the natural world may be necessary when designing policy and programing intended to support Indigenous people to age in place. I posit that attention should be paid to “place-ing” dementia prevention and care in the context of the natural and cultural environments that are significant to Indigenous people, and which may be supportive of personhood and wellness for people with dementia and their caregivers, when devising policy and programming related to aging in this population.

Setting

This research took place in Cartwright in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada (Figure 1). Cartwright is located at the mouth of Sandwich Bay, on the southern Labrador coast. The town has a population of 515 people (2011) who identify as Inuit, Innu, or settlers, or as having mixed heritage (Statistics Canada, 2017). Historically, Cartwright was a cod fishing centre and families in the region moved between seasonal homes and resource harvesting locations on a seasonal basis. Most often, they lived on the coast in the warmer months where they engaged in fishing and berry picking, and moved to sheltered areas in Sandwich Bay in the winter where they could hunt, trap, and gather firewood (Pace, Reference Pace2008). Because of changes in the economy, including the moratorium on Atlantic cod and salmon fisheries in the 1990s, the centralization of services in the town of Cartwright, and government resettlement programs in the 1950s through the 1970s, seasonal movement is no longer practiced (Kelvin & Rankin, Reference Kelvin, Rankin and Kennedy2014; Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2015). However, many community members retain strong ties to family homes and seasonal resource-gathering places (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy1995; Pace, Reference Pace2008). Some families continue to maintain properties at these locations, which they use as seasonal properties for recreation; and to engage in hunting, gathering, and fishing. As a result, the practice of moving around the natural environment remains central to the Southern Inuit way of life.

Figure 1: Location of Cartwright, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada

Methodology

This community-based, participatory research project employed a modified Photovoice approach as the primary method (Drew, Duncan, & Sawyer, Reference Drew, Duncan and Sawyer2010). Photovoice is a qualitative, arts-based research approach in which participants are asked to take photographs to represent their lived experience. In this approach, participant-generated photographs are used to elicit narratives, develop critical dialogue, and make community priorities and challenges visible to policy makers with the intent to influence social change and improve public health (Rapport, Wainwright, & Elwyn, Reference Rapport, Wainwright and Elwyn2005; Wang & Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1997). This approach is often utilized with marginalized populations to support them in making their voices heard (Rush, Murphy, & Kozak, Reference Rush, Murphy and Kozak2010).

Photovoice falls within the participatory research paradigm (Wang & Pies, Reference Wang and Pies2004), which aims to empower participants to self-define, actively contribute to the research process, and influence social change (Jennings & Lowe, Reference Jennings and Lowe2013; Minkler & Wallerstein, Reference Minkler and Wallerstein2003). Photovoice was selected for this project because of its potential to produce rich visual data, prompt storytelling, and allow participants autonomy in shaping the research questions. The potential to elicit stories was a strength of this approach, as this is a culturally salient way of sharing knowledge (Kovach, Reference Kovach, Strega and Brown2015). Of additional appeal was the potential to showcase participant photographs as part of the knowledge mobilization strategy. An underlying principle of this project was building authentic relationships and ensuring research relevance through consultation, consent, and dissemination by involving local Indigenous decision makers and community members throughout the research process (Bull, Reference Bull2010).

Photovoice typically involves participant training, a photography assignment, group discussion, and getting the attention of policy makers, community leaders, and other stakeholders through a public display of participant photographs and captions (Wang, Morrel-Samuels, Hutchison, Bell, & Pestronk, Reference Wang, Morrel-Samuels, Hutchison, Bell and Pestronk2004). For this project, the traditional Photovoice approach was modified by replacing group discussions of images with in-depth individual interviews centred around participant photographs, similar to the photo story approach described by Drew et al. (Reference Drew, Duncan and Sawyer2010). The justification for this approach relates to time and budgetary constraints associated with the remoteness of the community, as well as the potentially sensitive nature of participant experiences with aging, dementia, and care.

Approach and Subjects

This research began with the development of relationships with the NunatuKavut Community Council (NCC) and the community of Cartwright. The principal investigator collaborated with the NCC, a gatekeeper for research with Southern Inuit in Labrador, from early in the research process to ensure relevance of the research topic and methodological approach. The initial research question was inspired by discussions that the researcher engaged in with older adults living in Cartwright during a previous project (Pace, Reference Pace2008). Older adults from Cartwright were consulted about the research design in the early stages of project conceptualization. The NCC was also consulted early in the planning stages of the project, prior to grant submission, during ethics review, and on an ongoing basis throughout the project. The NCC expressed that they have very little data about the needs and experiences of the older adult population and that baseline information about health and aging would be beneficial. The project received approval and ethics clearance from the NCC and a research agreement was developed. The NCC also reviewed and approved drafts of research outputs including the photo book, poster, and community report. Research ethics approval was additionally granted by the McMaster University Research Ethics Board and the Health Research Ethics Authority of Newfoundland and Labrador.

Fourteen participants (3 male, 11 female) residing in Cartwright, NL participated in the project. Participants included adults 50 years of age and older, family caregivers, and home care workers. Thirteen participants engaged in the Photovoice assignment, and one completed an interview, but did not take photographs,Footnote 1 Prospective participants were approached by a local community research assistant who provided information about the project and extended an invitation to an information and training session. Six people participated in a group training session at the local senior centre, and eight were trained in individual sessions with the principal investigator at their own homes. Training involved providing participants with project details, reviewing Photovoice procedures and ethics, and explaining the informed consent process. Ample time was provided for questions and discussion with the researcher at each training session. Participants were provided with a point-and-shoot digital camera and given approximately one week to take photographs to represent their lived experience with aging, dementia, and/or dementia care.

As participants finished the photography assignment, they met with the principal investigator to discuss the content of their pictures. Interviews were informal conversations structured around the content of participant photographs. Participants took from 6 to 52 photographs each, with an average of 15 photographs per person. Participants were asked to describe each of their pictures, the reason they took them, and their significance. As they told stories related to their photographs, the researcher probed for detail as relevant topics emerged to draw connections between participant photographs and broader research themes.

Analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were coded and analyzed by the principle investigator during and after the field research trip. The qualitative data analysis software NVIVO 11 was used to store and organize data. Codes and themes were developed using inductive and deductive approaches (Joffe, Reference Joffe, Harper and Thompson2012) which involved journaling following interviews, deep reading of the transcripts (Rice & Ezzy, Reference Rice and Ezzy1999), and memoing (Birks, Chapman, & Francis, Reference Birks, Chapman and Francis2008) during transcription and coding. Data analysis was grounded in a critical interpretive theoretical framework (Scheper-Hughes Reference Scheper-Hughes1990). This framework situates health in the context of broad economic and political forces (Baer, Singer, & Susser, Reference Baer, Singer, Susser, Baer, Singer and Susser2003), recognizing that there are inequalities in health care and services to marginalized groups. Phenomenological thematic analysis was applied to both visual and interview data, as a means of understanding the lived experiences of project participants, and the embodiment of their experiences over the life course. An iterative and reflexive analytic approach was used which involved reviewing and sorting photographs into visual themes, matching photographs with the associated text from interview transcripts, and considering the overt meaning of the images as visual data as well as the meanings associated to images by participants during their interviews.

Knowledge Mobilization

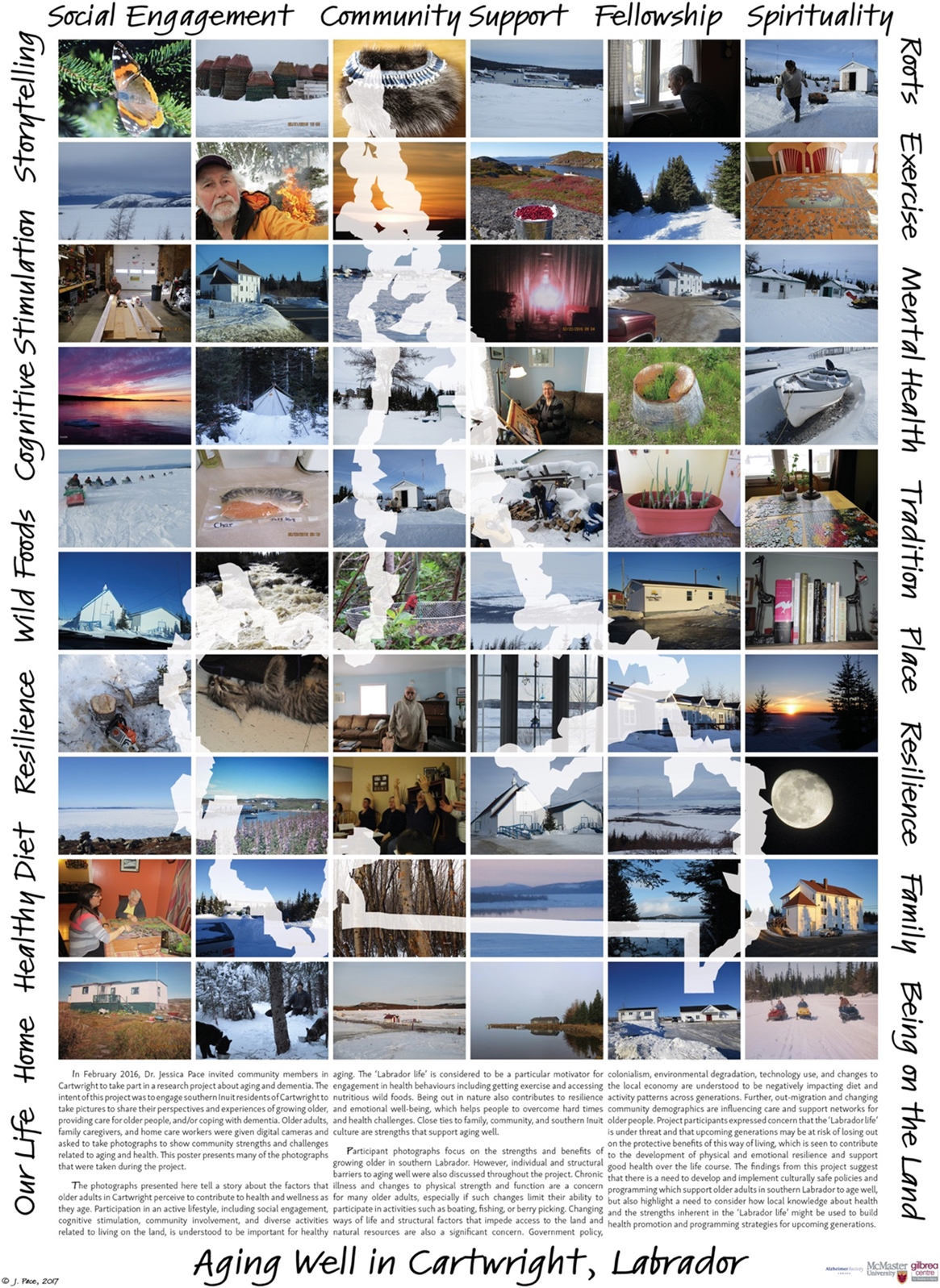

Following preliminary data analysis, the researcher returned to Cartwright to display a public photo exhibit at the Marion Centre (50+ Club). The exhibit presented participant photographs with associated stories, and provided an opportunity for community members to reflect and comment on the research findings and emergent themes. Two events were planned to showcase the photographs. The first was a supper for community members 50 years of age and older, to which key decision makers from the NCC, as well as local and provincial government officials were invited. The following day, all community members were welcomed to view and discuss the exhibit at a drop-in event. The events were well attended by community members of all ages, including most classes of the local all-grades school who came for a showing of the exhibit at the request of the school principal. Findings were formally reported to the NCC in the form of a written report as well as the development of a photo book which brought together photographs taken during the project and accompanying narratives. Copies of the photo books were donated to school libraries in all 11 NunatuKavut communities to ensure that the knowledge generated from this project remained within the communities; additional copies were provided to the NCC main office as well as to each individual participant. A poster (Figure 2) was also prepared to display the photographs in the Marion Centre (50+ Club) in Cartwright at the request of community Elders.

Figure 2: Poster depicting research findings

Findings

Research participants took over 250 photographs throughout the project, and the majority of these were representations of the natural world. It quickly became evident when viewing participant images, and listening to the accompanying narratives, that place and culture are major overarching themes within which aging, dementia, and care are experienced. Here, I present data that situate dementia prevention and care in the context of engagement with natural and cultural spaces in and around Sandwich Bay and explore some of the pressures that contemporary Southern Inuit perceive to limit them from engaging with the natural world.

Situating Dementia Prevention in the Context of Healthy Aging

Among Southern Inuit participants, strategies related to dementia prevention are closely related to practices that are perceived to be supportive of good health over the life course. In this setting, good health in aging is understood to be a direct outcome of life lived on the land in a time when and place where survival was reliant on the physically demanding work of subsistence and constant engagement with the geophysical world. Some participants reflected on the factors that shape good health in terms of previous generations, linking hard work, a supportive family and social network, physical activity, and acceptance of challenges as key contributors to resilience and well-being.

I’m sure there are things that we can do to improve our health as we grow older, you know, but I think for the previous generation, the generation before us, I think they did what they could to remain healthy, they worked hard, they were caring people and they worked harder physically than our generation did, you know, and today’s generation as well, I mean, they were slaves, really. It was a hard life, you know, but they accepted it and I think it contributed to their well-being. They had to be caring people, they had large families, they supported and needed each other, you know? (CG04)Footnote 2

Continued engagement with the land and a subsistence lifestyle – “our life”, or the “Labrador life” – remains a cornerstone of understandings of healthy aging and dementia prevention despite diverse pressures that have impacted the ability for Southern Inuit to participate fully in this lifestyle.

The “Labrador life” is perceived to provide the necessary supports for physical and mental health by providing opportunities for physical exertion and engagement (e.g., berry picking, shoveling snow, cutting firewood), nutrient-dense wild foods that contribute to a healthy diet (e.g., fish, berries, wild game), and engagement with the natural world, which is understood to support mental wellness. Aging in place, with access to well-established social networks and familiar places, is also understood to have protective benefits related to cognition.

I think activity...I’m certain of keeping doing the things you’re able to do, love to do, clearly would help with all that. The socializing is clearly part of the picture it seems to me, yeah, in my understanding diet has a place, and you can see the challenges with that in a place like this, and even organized activity, when you can no longer go on your own to the, to the fishing and the hunting, you know, or just outdoors. I’m sure the outdoors is a huge benefit, the places that are really important to you, you know what I mean? ‘Cause it’s the familiar…and going to familiar places just brings back the memories, we all know. Even now I go somewhere and I say, “oh yeah, this happened here”…and whatever times, good or bad, they spark the memories and I think sparking memories just can never be bad, unless they’re terrible, nasty, traumatic things, but for the purpose of memory it still must be good, pure, active memory. (CG02)

In this context, healthy aging is understood holistically in relation to a combination of factors including engagement, activity, good health, a positive attitude, and social connectedness. Cognitive health is understood to be directly related to these factors, one of which is challenging one’s brain. Activities such as reading, journaling, and doing crossword and jigsaw puzzles were described as advantageous. However, engagement with land-based pursuits is seen to have special benefits, including providing challenges and time to think things through.

I don’t do any real mind challenges other than living the way I always lived…I mean, it’s a repetition, but in the meantime while I’m there [outdoors], I mean, I’m thinking politics, I’m thinking family, I’m thinking everything while I’m at it and there’s nothing to clutter it up besides that, because the woods part just comes natural. I just, you know, it’s like walking, you can walk and talk at the same time, and do these things, but, you know, there’s things in my life that I think about while I’m at it, like my daughter is going through a divorce, and that stuff passes through my head every time I’m in there, but as far as finding ways to physically be able to measure it, I don’t know if you can do it or not. (S03)

In contrast to the busyness and stress of everyday life, spending time enjoying the natural world is perceived as providing time to think, reflect, and be calm (Figure 3).

That’s the mountains, and I dearly, dearly love the mountains. I said, “I got to put the mountains in ‘cause I so love those mountains.” I go over to the gas station every week and I’m quite sure that the reason I go is so I can look across the bay at the mountains in the spring, in the fall, see how much snow is on, how much, how fast the snow’s melting, and how much is left, and I do that all the time. I will not go to the gas station here (closer to home) when it’s open over there. I really don’t know what [the mountains] represent. I guess it’s… peace. I think to, you know, to be able to go over and sit down or sit, look, watch while he’s filling up the gas and just look and see the peace and quietness there…I’m always looking to see if anything is moving there, anything there, anything on the mountains moving, but that’s me. (S04)

Figure 3: “I got to put the mountains in ‘cause I so love those mountains” (S04)

Several older participants explained that when they spend time outdoors they constantly use their minds by observing the world around them, tracking seasons, weather, and the movements of animals, or navigating new or familiar routes across the land, sea, and ice.

In addition to the factors described, time spent with people is recognized as crucial for brain health. Loneliness and isolation were described as risk factors for developing dementia, whereas social contact was seen as protective against cognitive decline.

I think it’s, like, don’t be left alone, like, have family around, and be able to talk all the time. Like, I think a big part for dementia, this is only my own theory, but it’s if you’re left alone too much by yourself, probably, and you know…Loneliness, yeah, not having much, [interest] into like, different things like books or…I think that plays a big role into keeping your mind going like, books and crossword puzzles, anything, newspaper, yeah. (CG01)

Participants described that seeing other people regularly was good for the brain and for mental wellness. Visiting and social gatherings were perceived to spur laughter, storytelling, and reminiscence, which were described as supportive of memory as well as the reinforcement of collective identity and shared experiences (Figure 4).

Bringing the seniors together socially is good, that’s a good thing, because they’re able to interact with each other and reminisce and I find one of the things that we do, there, monthly is the last Saturday of each month we have a music and friends’ night and it’s a time to reminisce and sing some of the old stuff that they used to and they seem to really enjoy that, right? They talk about the old days as well, so it’s a new venture for the community. The Marion center only opened a year or so ago. (CG04)

Figure 4: The Marion Center 50+ Club, Cartwright (CG04)

Continued participation in activities located “in place” on the land, sea, and ice in and around Sandwich Bay is considered to tie people to their individual and family histories, knowledge of geography and natural resources, and the skills needed to survive, and to support the maintenance of “Southern Inuit” and “Labradorian” identities, which are central to local notions of personhood.

I think so. I really think so – healthy physically and mentally-emotionally, I think. Because it’s such an important part of – you identify this is partly who I am, right? In a changing world that [way of life] is still there and you can do it and it’s very, very important and I think you just, if you’ve been kicking around you see people they just, that’s what they do, they’re not just – it’s not just an outing for the day it’s a re-connection every time. Because, you know, the tent is one of the ways we lived so much, yeah. (CG02)

Place-ing Dementia Care: Supporting Personhood and Identity in Place

Knowledge of dementia was somewhat limited among participants. However, dominant understandings of the condition relate to the perception that a person with dementia experiences a loss of self or identity and difficulty connecting to the world around them.

I thinks of someone who is…their mind is gone, they forgets people around them, they forgets their surroundings…but to look at them, there’s nothing wrong. Yeah, but you can tell, like, day by day, that they’re slowly going a little further, like, they goes back to almost like a childhood. (CG03)

A search for “home” was a recurring theme in descriptions of the condition.

I used to work for [a client] and there was like guaranteed, every evening around that time, actually, he’d be wanting to go home, but we didn’t know where home was, but he wanted to go home. Like, you know, time do stand still for some of them. Yeah, and usually like every evening around that time that he’d start getting like that. (CG03)

With regard to care, support provided “in place” in the local community was preferred, as it was perceived that being forced to leave the community to access care was detrimental to older peoples’ well-being.

I think when seniors have to go away, I think it’s really negative on their lives, right? They’re so used to home and having, they worked hard, I know this lady personally and she raised a large family and for her to have to go away to live in a home I think that would be detrimental to her health. (CG04)

Family were therefore the desired care providers for people with dementia who continued to live in Cartwright, with family care sometimes being supplemented with support from a paid home care worker. Despite the preference for home care, individuals with dementia ultimately tend to end up in long-term care when the services in their communities become insufficient to support them to live at home.

Approaches to caring for a person with dementia were centred around love, empathy, and compassion. Trying to empathize with a person with dementia and “follow in their tracks” (CG03) (Figure 5) were emphasized. Patience and acceptance were described as key values.

I recall a senior lady that lived close to us when we were younger, that she had, uh, we didn’t know what it was then, we just said it was growing old, but we saw her doing things that were out of the ordinary, you know, and not, not normal as you would call normality, you know. Her family really cared for her, looked after her and loved her, you know, they accepted the fact that mom wasn’t the same as she was at one time, you know? (CG04)

Figure 5: “Try and follow in their tracks and try to understand what goes through their minds” (CG03)

Caring for a person with dementia involves supporting them to continue to live in their home for as long as possible by providing social support and assistance with activities of daily living. However, families also described strategies to “ground” people in their place and time, which seemed to be related to reinforcing their identity. This approach involved using family photographs or the view out the window to help orient a person who was experiencing confusion (Figures 6 and 7).

This picture (Figure 6) is the view from my father’s chair who suffered for only a couple of years with dementia. This is one of the scenes that we helped anchor him at times to his time and place, that was the purpose of it, to kind of ground him a bit…We’d point out to him, this is his wharf, this is the harbour that he always looks at, and that’s Big Hill, and so on. That was an important scene to him, that’s where he spent so much time on that wharf. (CG02)

Figure 6: “This is one of the scenes that we helped anchor him at times to his time and place” (CG02)

Figure 7: “He was failing quite seriously up till then but as soon as we were out in the boat and going the stories rolled, everyplace. Everyplace had a story” (CG02)

Engaging in cultural activities and/or taking a person with dementia out onto the landscape were perceived to have special benefits. The immersive experience of being out of doors and surrounded by familiar sights, smells, and sounds was perceived to spark memories that could help to orient a person and stimulate reminiscence (Figure 7).

He lived in this spot where you see this scene, well, this scene changed a little bit, like some of the buildings and stuff. Him and my mom lived in that house for over 60 years, but somewhere he lost track of where home was. So, we tried to search for that…as you know, it doesn’t work. He’d been born here in Cartwright, not far from that house, and then he spent quite a few years just 5 or 6 miles up here at Muddy Bay, so sometimes we thought that might be it. We did get up to there, I think I was telling you that story. He was failing quite seriously up till then but as soon as we were out in the boat and going the stories rolled, everyplace. Everyplace had a story. Some from his childhood days and some from times we shared and other family, they just kept rolling and they didn’t stop. At a certain point he got tired and wanted to go home, but until then he was amazing. I think that’s probably good for all of us, like. I think when you get into those kinds of spots where he was I think it’s definitely good, yeah. (CG02)

In line with this idea, another participant – who had previously provided care to a parent with Alzheimer’s disease – described that she had instructed her family that if she were ever to develop dementia, she would prefer to be surrounded by belongings that connected her to the outside world (Figures 8 and 9). She felt that having her photographs displayed in a slide show and natural/found materials that she utilized for crafts (e. g. driftwood, sea glass, wild grass) placed around her so that she could easily reach them would help her to feel that she was able to see the sights, smell the smells, and feel the textures that connected her to her life and her favourite places even if she were confined to a room in long-term care.

Figure 8: Rushing Brook...”I can feel the energy. Energy that I can use when I get back to my home” (S05)

Figure 9: Grasses by the landwash

Disconnection: Barriers to Place-Based Engagement in Aging

Although continued engagement in place was understood as central to aging well among Southern Inuit, participants described numerous barriers that impeded older people from accessing the natural and cultural spaces and places that they so closely link to identity and health. For example, structural pressures are restricting access to the land and natural resources through mechanisms such as government regulations around hunting and fishing rights.

I suppose it’s federal, as far as fish is concerned, because federal looks after the fish, but the province looks after the caribou and the others, in season…My growing up, you know, you fished for salmon and char and trout and that for the whole summer, like, but you never took any more than you needed but now they’ve got this little window, probably about two weeks when you’re allowed to take. (S03)

The generation that is aging now has experienced many facets of governmental control of access to land and resources over their lives, including widespread resettlement programs in the 1950s through 1970s, the military presence in their community in the 1950s and 1960s, residential schools, the loss of the caribou hunt, and the moratorium on the Atlantic cod fishery in 1992.

The health of the local environment also impacts the way that residents of Cartwright engage with the land. Participants described concerns related to climate change as well as environmental contamination such as PCBs, which were dumped by the American military when they closed their base in Cartwright in the late 1960s. Many community members actively avoid gathering resources from around the site of the base for fear of ingesting the PCBs that have infiltrated the food chain. Another pressing concern is large-scale development and resource extraction projects in the region including the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project, which has raised significant concerns about the potential for methylmercury contamination. This issue was at the top of people’s minds when I returned to the community to display the photo exhibit, as Muskrat Falls was actively being protested by Land Protectors at the time.

The capacity for older people to be cared for in the community was also a concern for many participants. They perceived that many in the younger generation were less interested in supporting older community members.

It’s a generation that don’t want to – can’t take the time to care, you know, for the elders, they can’t do it, they just - everything is all about them and, you know, yeah, cause when we were kids growing up, we’d shovel out somebody’s door or we’d bring in someone’s clothes just to do it, I mean we always did it around all the community, right? And we used to visit the old people, go in and visit them and sometimes we’d just stand by the door and then we’d go in and, but all the kids done it, you know, we always did that. (S01)

Changing values and ways of living, and an influx of new technologies, combined with limited economic opportunities in the region have greatly reduced the availability of family in the community to support older people to stay in-place as they age. Outmigration is common for the younger generation as they seek employment and education. Formal supports are also limited in the region; there is no assistive housing for older people in the community of Cartwright, and only one personal care home and one long-term care facility in southern Labrador.

In addition to the abovementioned factors, which may limit peoples’ ability to stay in their community and access natural resources, changes to health and ability associated with aging can also make it more challenging for older people to continue to engage with the natural world. Participants described that changing mobility could alter their ability to travel on the land, especially independently.

One thing that worries me is the – losing mobility – right, and not be able to do…because the heart still wants to do what it wants to do and like, [Peggy] used to, I used to try to get her to come berry picking, I said, or we could just walk on the hill or something, and she couldn’t do it, she wanted to do it, her heart wanted her to do it, but she couldn’t do it. And I found that sad, you know, when she started losing her mobility and then she had to have a walking stick…that would hurt, to have all those feelings, to want to do all those things that mean so much, and then not be able to do anything would be the worst. (S01)

For some people, particularly women, changes to their spouse’s health or mobility was as much a concern as their own. This often altered their ability to access the land, as it is men who are usually the primary boat driver (Figure 10).

That’s what we spend a lot of time in ‘cause we leave here and go to Spotted [Island] in speedboat, and this one we’re leaving to go, but that boat, we’ve done a lot of going, like, [my husband] and I up around the…I think that’s what I miss most though, you know, where he can’t really go what he used to, ‘cause we would just leave here and we had a small cabin just not too far from here, so we went there and then we’d go on to Table Bay, or you know, some of the…just to see things there…I just like to be outdoors, I like to look around, I like to know where everything is. (S02)

Figure 10: “I just like to be outdoors. I like to look around. I like to know where everything is” (S02)

For couples who, for example, engaged in fishing excursions or trips to the cabin together, changing mobility acts to significantly limit their access to the land, especially if they have no adult children living in the community to support them in travelling via these means. In this regard, changing mobility was in some ways more of a fear for older people than the possibility of developing dementia.

Discussion and Conclusions

Photographs taken by Southern Inuit participants, and the narratives that accompany these images, reveal that experiences of aging, dementia prevention, and care are deeply situated “in place” in the natural environment and cultural spaces surrounding Sandwich Bay. The relationship between place and dementia in this setting is reflective of the life-long embodiment of engagement in cultural, economic, social, subsistence, and leisure activities embedded in the geophysical world, and the grounding of personhood and identity in relationships with particular places that are used for activities including hunting, gathering, fishing, and travelling. For older adults living in southern Labrador, place and nature provide the key building blocks that support good health throughout the life course and into old age, including those that are understood to be protective of brain health.

Southern Inuit older adults describe dementia prevention in terms of healthy lifestyle behaviours, which include practices such as eating a healthy diet, getting physical exercise, engaging the brain through diverse and challenging activities, reducing stress, and adequate social contact. These factors are reflective of recommendations that are well accepted in the biomedical health promotion literature related to cognitive health (Alzheimer Society, 2010). However, in this setting, these behaviours are consistently framed as place embedded and situated in engagement with the natural world over the life course, which should be considered when developing policy and programming for this population.

Several exemplars were given of cultural activities that were understood to benefit cognitive wellness. Harvesting firewood, for example, requires the use of knowledge of the land and the location of suitable wood, navigation skills, and the ability to drive both a car and a skidoo, as well as snowshoeing, chopping, and stacking wood, which provide physical exercise. Procuring firewood also involves a significant amount of time spent outdoors, which is understood to provide stress relief and time to think. The process of procuring firewood also links individuals to their past and the knowledge of their ancestors, while resulting in an important resource that helps people to heat their homes, and as such, offers motivation for engagement because of the necessity of the task. These findings are similar to culturally grounded understandings of dementia prevention, which have been documented in other Indigenous settings and, in line with other studies, emphasize the holistic and relational elements of caring for cognitive health (Pace, Jacklin, Warry, & Pitawanakwat, Reference Pace, Jacklin, Warry, Pitawanakwat, Hulko, Balestrery and Wilson2019). The multifaceted benefits (physical, economic, dietary, social, cognitive, and emotional) of activities grounded in place and culture cannot easily be replaced or simulated if people must leave their homes and communities to receive care.

In the NunatuKavut region, the generation that is aging now was raised during a time when life was intensely physical and highly dependent on knowledge of the land, including how to travel within it and harvest and process the resources it provided (Hanrahan, Reference Hanrahan2000). Older adults perceive this to be a significant source of resilience. However, over the course of their lives, this cohort has witnessed rapid and ongoing pressures on their culture, way of life, and the environment, which have so deeply shaped their livelihood. Colonial practices including residential school and forced resettlement programs, environmental degradation caused by large-scale resource extraction and development projects, and an influx of new technology in the last half century have impacted the way Southern Inuit engage with the land and each other (Kennedy, Reference Kennedy2015). As this population ages, they are reflecting on changes in their health, their capacity to age in place, changing care and support structures in their communities, and their roles as cultural knowledge keepers. Although dementia is a concern, passing down knowledge of the land and supporting cultural continuity for younger generations is perhaps a more pressing issue. Older adults perceive that younger generations are at risk of losing the protective benefits gained from life lived on the land and therefore at risk of poorer health as they grow older. Consequently, dementia was framed as only one threat to identity in the context of a changing world.

This research highlights that experiences of aging, dementia, and care among Southern Inuit resemble those of other Indigenous peoples in Canada, including a shared desire to age and die at home in their own communities and the challenges associated with pressures on “traditional” ways of living (Gorospe, Reference Gorospe2006; Hotson, MacDonald, & Martin, Reference Hotson, Macdonald and Martin2004; Hulko, et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Improving End-of-Life Care First Nations Communities Research Team, 2017; Pace, Reference Pace2013). However, aging in place is often difficult for a population with high rates of chronic illness and early-onset frailty (First Nations Information Governance Centre & Walker, Reference Walker2017) in regions where specialized medical care and home care services are often unavailable or difficult to access (Hotson et al., Reference Hotson, Macdonald and Martin2004). In such settings, the availability of informal supports at the community level, such as family care, are also in flux because of factors including a lack of economic opportunities, which lead to the outmigration of younger generations (Habjan, Prince, & Kelly, Reference Habjan, Prince and Kelley2012). Additionally, the realities of climate change and environmental degradation are making it less safe to engage in some land-based practices (King & Furgal, Reference King and Furgal2014) or to access the land at all (Cunsolo Willox, et al. Reference Cunsolo-Willox, Harper, Ford, Landman, Houle and Edge2012).

Research with Indigenous peoples has consistently indicated that there is a deep connection between land and health, and increasingly the link to mental and emotional health is being emphasized (Cunsolo Willox, et al., Reference Cunsolo-Willox, Harper, Ford, Landman, Houle and Edge2012; Ostapchuk, Harper, Cunsolo Willox, Edge, & the Rigolet Inuit Community Government, Reference Ostapchuk, Harper, Cunsolo-Willox and Edge2015). Evidence suggests that a loss of access to the land can contribute to feelings of social isolation and depression among older people, which are known risk factors for dementia. Therefore, as research about the benefits of land-based engagement and mental health develops, the impacts on cognitive health in aging should not be overlooked. As we develop a stronger understanding of the impacts of participation in land and culturally based engagement on wellness over the life course, attention should be paid to ways in which engagement with natural places, spaces, and materials can be incorporated into policy and programming for older people with dementia living both “in” and “out of” place.

In reflecting on culturally safe care and support for Southern Inuit adults transitioning into older age, and potentially dementia, it is important to consider how conceptions of personhood and the significance of relationships to place, culture, and the natural world play into overall notions of health and wellness. Attention should be paid to how such elements might be considered in developing strategies for optimal dementia care. In the biomedical literature, caring for personhood includes the recognition that people with dementia remain people despite disease symptoms that might hamper their ability to communicate with the world around them. To be effective, however, person-centred care must be respectful of notions of what constitutes personhood in diverse settings and endeavour to address supports to identity and personhood, which are relevant to the person receiving care. Culturally safe care for Southern Inuit living with dementia must be grounded in an understanding of the relationship between health and place, space, tradition, and culture, and must consider access to the natural environment to be a central contributor to quality of life.

Experiences of dementia, prevention, and care in Southern Labrador are deeply connected to place and culture. However, diverse factors including the impacts of colonization, economic and environmental change, outmigration of younger generations, shifting cultural values, and individual health and abilities all impact the capacity of older people to engage with the natural environment and to receive care at home. There is a need for policy and programming in this region to consider the unique needs of Southern Inuit who live in remote communities in the context of changing social supports and community structures. For example, consideration should be given to ways of supporting older people to maintain relationships with the land, land-based resources, and culture as they age. This may entail implementing programs that support older people in accessing the land, making wild foods available to older adults who are no longer able to procure them (including those living in long- term care), and developing programming for older people that is culturally relevant. Reflecting on the limited care options for older people in the region, and the potential detriments of moving away from one’s community, there may be benefits in considering how housing options and social supports such as senior’s centres might work together to support older people, especially those with limited mobility or other risk factors for social isolation, to stay engaged and remain in their communities longer. This could be achieved by housing such services in the same building complex as each other or in close geographic proximity to each other. Privileging opportunities for intergenerational teaching and knowledge sharing would likewise support the fulfillment of meaningful roles for the older population, while also benefiting younger generations.

There is a need to empower Indigenous people, including older adults, to continue to engage with land-based practices in the natural world over the life course, so that they might continue to benefit from the supports to identity, indigeneity, and healing that are inherent in these practices (McCormick, Reference McCormick, Kirmayer and Valaskakis2008). For this to happen, there is a need for innovative policy and programming related to health promotion as well as a focus on the development of stronger home care supports and services emplaced within the context of culture and the land.

Limitations

Most the older adults who were interviewed were relatively young (62–73 years of age) and quite active and engaged in their community. This limits the range of perspectives presented and does not account for people who may be socially isolated, less mobile, or otherwise less able to participate in a project of this type. No participants who identified as having dementia were recruited, although three older adult participants spoke of changes to their memory or events in which they had experienced memory loss. The small sample size may limit the generalizability of the research findings. Finally, despite many benefits of the Photovoice approach, the camera/photography assignment may have been a barrier to some older adults, particularly those with low knowledge of technology or limited mobility. Efforts were made to accommodate everyone who expressed an interest in participating: for example, by allowing people to participate only in the interview, or offering additional training on how to use a camera.