Introduction

Age-related dementias have become a significant health concern around the world. In Canada, approximately 500,000 people are thought to have age-related dementias. This number is projected to more than double to 1,125,184 over the next 30 years (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2010). Dementia has also been identified as an emerging health issue in Indigenous communities globally (Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, Reference Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry and Whitmer2016; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Flicker, Lautenschlager, Almeida, Atkinson and Dwyer2008) and in Canada (Jacklin, Walker, & Shawande, Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013). Recent research suggests that rates of dementia may be 34 per cent higher in First Nations populations than in non-First Nations populations in Canada, and that rates are also rising more quickly (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013). This, coupled with the finding of a unique epidemiologic presentation in this population, such as a younger age of onset and higher prevalence in males, suggest it is time to review what is known about dementia in this population. Age-related dementias, particularly Alzheimer’s disease, are argued to be “newer” illnesses in Indigenous peoples. It is suggested that because of improved life expectancy and an expanding senior population, Indigenous peoples are beginning to experience a new magnitude of age-related dementias (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Walker and Shawande2013). These trends have led researchers to specifically suggest that understandings of cultural influences concerning dementia in Indigenous peoples should be a priority research area (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002). Effectively, these trends imply that Indigenous people may be in a transitionary period in which they are negotiating cultural and biomedical meanings of this illness, which will in turn impact their health care seeking behaviours, and how they respond to biomedical treatment and care (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002; Whitehouse, Gaines, Lindstrom, & Graham, Reference Whitehouse, Gaines, Lindstrom and Graham2005).

Concerns have been raised regarding the recent increase in cases of dementia in Indigenous communities, where traditionally low rates along with relatively smaller older adult populations have led to a lower prioritization of dementia than for other illnesses (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007). As dementia is expected to be an increasing challenge for health care service delivery in Indigenous communities, the current lack of foundational information makes planning and responding to this growing issue difficult for communities and service providers (Lanting, Crossley, Morgan, & Cammer, Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007).

In this article, we present a review and consolidation of knowledge concerning cultural influences on dementia in Indigenous populations in Canada. This work was originally undertaken by the authors in 2012, in response to a request from Health Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, to identify and synthesize available knowledge and provide recommendations to inform the First Nation’s and Inuit Home and Community Care (FNIHCC) Program. Our guiding research question is: what is known about how culture influences experiences with dementia in Indigenous people in Canada? Specifically, we assess and report on the published and grey literature concerning the cultural construction and social mediation of the experience of dementia by Indigenous peoples, and how this affects experiences of care. It is well established that culture influences an individual’s understandings and behaviours around illness. This includes what people believe has caused their illness, how they think it should be treated, health care seeking behaviours, decision-making models, and what are considered appropriate models of care (Kane, Reference Kane2000; Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, Reference Kleinman, Eisenberg and Good1978). In dementia care, culture has been shown to influence individual and family experiences with the illness (Kane, Reference Kane2000). Understanding patients in the context of their culture and history is considered vital to the implementation of cultural safety in health care and the improvement of health outcomes. Without this understanding of culture, it is not possible to develop appropriate mechanisms for diagnosis, treatment, and care; as such, it becomes impossible to achieve health equity for Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Methods

The review is best characterized as a qualitative systematic review also referred to as a “qualitative evidence synthesis” (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009). Such reviews serve the purpose of broadening understandings of a particular topic through the synthesis of findings from qualitative studies. Qualitative evidence syntheses are appropriate to explore health-related questions such as “how do people experience illness,” and health systems questions such as “what are the barriers and facilitators to accessing health care” (Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Hannes, Booth, Harris, Harden, Popay, Higgins and Green2013). The approach normally involves the development of a search strategy (inclusion/exclusion criteria), a critical appraisal of the studies identified, thematic analysis, and synthesis (aggregative, narrative, or interpretive) (Grant & Booth, Reference Grant and Booth2009; Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Hannes, Booth, Harris, Harden, Popay, Higgins and Green2013). It is noted that there is greater flexibility in qualitative evidence syntheses than in other systematic reviews and that there is continued debate over the need for comprehensive, exhaustive searches and quality assessments (Noyes et al., Reference Noyes, Hannes, Booth, Harris, Harden, Popay, Higgins and Green2013).

We undertook a review of published academic and grey literature on age-related dementias in Indigenous peoples in Canada using two separate search strategies: one for peer-reviewed, academic literature and one for grey literature. A grey literature search was included to ensure that we captured other forms of dissemination on the topic. It is recognized that dementia in Indigenous populations is a recent topic of investigation and, therefore, it is reasonable to assume that data may be available from theses, dissertations, and Indigenous organizations that have not been published in peer-reviewed journals.

This review builds on a previous review conducted to inform the Trends in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias among First Nations and Inuit (Jacklin & Walker, Reference Jacklin and Walker2012). The purpose of the original review was to summarize the current state of knowledge regarding dementia among First Nations and Inuit in order to inform the FNIHCC Program 10 year strategy. This review concerns the systematic qualitative literature search under the general topic of “cultural considerations in diagnosis and care.” The original project included the following additional four knowledge domains not reported in this review: (1) incidence, prevalence, and rates of dementia in Aboriginal peoples; (2) dementia detection, screening, and diagnosis in Aboriginal peoples; (3) co-morbidity, social determinants of health, and risk factors in Aboriginal peoples; and (4) prevention and awareness campaigns aimed at Aboriginal people.

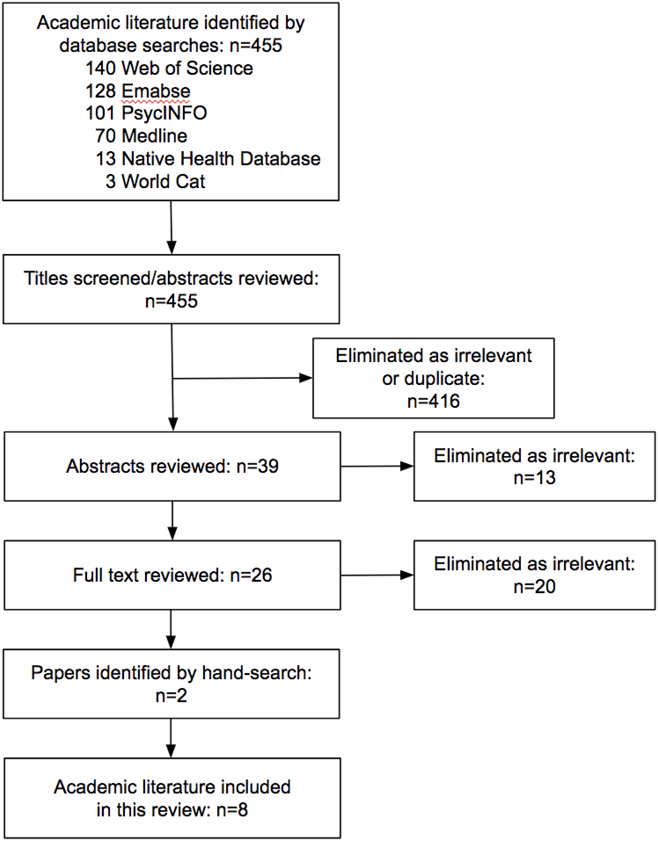

Academic articles and abstracts concerning this topic were identified through searches of the following databases: Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science), Embase, PsycINFO, MEDLINE®, Native Health Database, and WorldCat. These premier bibliographic databases were selected because of the quantity of reliable, quality scientific biomedical literature. Appropriate key words, (Tables 1and 2), were used to identify literature focused on Indigenous peoples, and combined cognitive decline and culture. We included academic literature published between 1975 and 2017. This time period could be consistently searched in the various databases. A single reviewer conducted a database search, which resulted in a total of 455 articles, as indicated in Figure 1. Articles were screened for relevance to the topic using the following criteria: (1) research focused on Indigenous dementia and/or dementia caregiving; (2) research was conducted with Indigenous people in Canada; and (3) culture was a variable in the analysis. To eliminate bias, a second reviewer also screened the titles of the articles identified in the search (n = 455). Of the 455 articles identified, 416 were eliminated by screening titles and removing duplicates; and an additional 13 articles were eliminated after reviewing the abstracts, resulting in 26 articles for full text review; 2 additional articles were identified by a hand search. The first author (K.J.) undertook a critical appraisal of the remaining articles in relation to our criteria, which resulted in the inclusion of eight academic articles. In our analysis primacy was given to Canadian references; however, because of the sparseness of available literature, studies from the United States were included at the authors’ discretion; for example, only one article in Canada touches on interpretations of symptoms, so we include a seminal U.S.-based study with Choctaw in this analysis.

Table 1: Keywords and search strategy for Indigenous cultural considerations in diagnosis and care

Table 2: Search results for Indigenous cultural considerations in diagnosis and care

Figure 1: Flow diagram of academic literature database search results

Grey literature was included as an important contributor in providing balance to the academic literature and to minimize potential publication bias (Mahood, van Eerd, & Irvin, Reference Mahood, van Eerd and Irvin2014; Paez, Reference Paez2017). Grey literature may include theses, dissertations, non-peer-reviewed articles, organizational materials, and technical reports. To maximize search sensitivity and keep results manageable and relevant (Wilcynski & Haynes, Reference Wilcynski and Haynes2007), the grey literature search was limited to Canada for the years 1975–2017. The search strategy included identifying a list of relevant organizations, Web sites, databases, and search engines following the model outlined in “Grey matters: A practical search tool for evidence-based medicine” produced by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) (2015). The CADTH model was selected as the preferred comprehensive tool to obtain Canadian grey literature because it provides a grey literature checklist and guidance on relevant topics with related database search tools.

In cases in which the Web site had an effective embedded search engine, we used the following sets of search terms, as appropriate: set 1: Aboriginal, First Nations, Inuit, Métis, Indigenous; set 2: dementia, Alzheimer, memory. In cases in which the Web site did not have a search engine or the previously described search generated no results, we browsed the site for related reports, news items, and other relevant documents. Grey literature was assessed by the authors for relevance, source of information, and quality of information as determined by a critical review of the document. Once identified and reviewed for relevance, the academic and grey literature citations were entered into EndNote bibliographic management software with a summary and thematic tags.

An inductive analysis of the relevant academic and grey literature was undertaken, with memoing in the margins to develop initial codes (Finfgeld-Connett, Reference Finfgeld-Connett2014). Our approach to the analysis of the identified literature is informed by the Indigenous social determinants of health model (Loppie Reading & Wein, Reference Loppie Reading and Wein2009). This framework recognizes that Indigenous health is affected by a complex interplay of historic, environmental, social, political, cultural, economic, and behavioural factors over each individual’s life course. In this model, distal determinants include historic, political, social, and economic contexts, such as the effects of residential schools and the Indian Act (1985). Intermediate determinants include community infrastructure, resources, systems, and capacities. Proximal determinants are more immediate factors such as health behaviours and physical and social environments (Loppie Reading & Wein, Reference Loppie Reading and Wein2009). We acknowledge that the distal, intermediate, and proximal determinants are a complex interconnected web that is impacted over the life course. In this review, we focus on culture as a determinant of health that is influenced at each of these three levels.

Results

The database and hand searches resulted in eight relevant peer-reviewed publications specific to culture and Indigenous experiences of dementia or dementia caregiving in Canada (Table 3). Of these, five of the articles focus on some aspect of culture and experiences of dementia; and three focus on caregiving specific to dementia. However, we note that some sources touch on both cultural understandings and caregiving. Other articles concerning Indigenous experiences of illness and aging were included as needed to fill key gaps in knowledge, but these articles are not identified in our search results or results tables. Specifically, we reference articles relevant to Inuit mental health and aging (Collings, Reference Collings2001; Kirmayer, Fletcher, Corin, & Boothroy, Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Corin and Boothroy1994; Kirmayer, Fletcher, & Watt, Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009); dementia and culture in U.S.-based studies (Boss, Kaplan, & Gordon, Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995; Henderson, Reference Henderson2002; John, Hennessy, Roy, & Salvini, Reference John, Hennessy, Roy, Salvini, Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson1996), and research on Indigenous caregiving and institutionalized care that are not specific to dementia (Brown & Gibbons, Reference Brown and Gibbons2008; Buchignani & Armstrong-Esther, Reference Buchignani and Armstrong-Esther1999; Chapleski, Sobeck, & Fisher, Reference Chapleski, Sobeck and Fisher2003; Graves, Smith, Easley, & Kanaqlak, Reference Graves, Smith, Easley and Kanaqlak2004; Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1995; Jervis, Boland, & Fickenscher, Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010; John, Hennessy, Dyeson, & Garrett, Reference John, Hennessy, Dyeson and Garrett2001; McClendon, Symth, & Neundorfer, Reference McClendon, Symth and Neundorfer2006).

Table 3: Relevant academic literature for Indigenous cultural considerations in diagnosis and care

The grey literature search strategy and hand search identified 10 relevant resources specific to culture and Indigenous experiences of dementia or dementia caregiving in Canada (Table 4). The resources include: one Master’s thesis (Cammer, Reference Cammer2006); one dissertation (Pace, Reference Pace2013); and two online reports (Native Women’s Association of Canada, 2013; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007); as well as five fact sheets, a corresponding model and methodology report (Jacklin, Blind, Jones, Otowadjiwan, & Warry, Reference Jacklin, Blind, Jones, Otowadjiwan and Warry2017; Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Jones, & Webkamigad, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Jones and Webkamigad2017a, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Jones and Webkamigad2017b; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Blind, Jones, Otowadjiwan and Warry2017; Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Webkamigad, & Jones, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Webkamigad and Jones2017a, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Webkamigad and Jones2017b, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Webkamigad and Jones2017c).

Table 4: Relevant grey literature for Indigenous cultural considerations in diagnosis and care

Together, the available resources were analyzed and categorized into five thematic areas related to how culture may influence experiences of dementia: (1) Indigenous understandings of dementia, (2) theories of causation, (3) interpretation of symptoms, (4) caregiving, and (5) Indigenous medicine. The Indigenous determinants of health became a cross-cutting theme in the five thematic areas. The extent of information available for each theme is not consistent, with more information available in the areas of Indigenous understandings.

Indigenous Understandings of Age-Related Dementias

Our knowledge of how Indigenous peoples experience dementia is limited (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995; Finkelstein, Forbes, & Richmond, Reference Finkelstein, Forbes and Richmond2012; Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Webkamigad, & Jones, Reference Jacklin, Warry, Blind, Jones and Webkamigad2017b). Most research with Indigenous peoples to date has found that the biomedical construct of dementia, in which dementia is perceived as a disease, is not well understood, and that often the illness is not viewed as problematic. The studies and reports we reviewed that discussed dementia in an Indigenous framework included participants who described dementia as a “natural” part of the “circle of life.” This was the case for the Secwepemc in British Columbia (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010), for communities in rural Northern Saskatchewan (Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011), for multiple communities in Ontario (Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012; Pace, Reference Pace2013), and Ojibwe in the United States (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995). A study with Secwepemc communities in British Columbia found that community EldersFootnote 1 held differing perceptions of dementia and that these understandings have changed over time (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). Understandings included Secwepemc beliefs that dementia was a part of “going through the full circle of life” (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010, p. 308). In Saskatchewan, Grandmothers described dementia as going “back to the baby stage” and part of the “circle of life” (Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011, p. 109). These ideas were similar to those in a study among Ojibwe in northern Minnesota in which female caregivers explained “part of her life was just part of the circle of life; she became a little child again” (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995, p. 8). During a roundtable gathering in Ontario, Indigenous participants from on- and off-reserve communities in Ontario described dementia as part of the natural life cycle and a return to the stage of infancy (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007). The cultural understanding of dementia as “normal” and as part of “the circle of life” was consistent among diverse Indigenous communities in Ontario, including the Haudensaune people of Six Nations of the Grand River Territory in Southern Ontario, and the seven rural Ojibwa, Odawa, and Pottawatomi First Nations of Manitoulin Island in Northeastern Ontario (Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Arguably, the view of dementia as “normal” is widespread across many non-Western cultures (Botsford, Clarke, & Gibb, Reference Botsford, Clarke and Gibb2011); however, the nuances of how “normal” is defined and understood vary considerably. In the studies from Indigenous peoples cited, the cultural framework of the medicine wheel and the circle of life provide context for Indigenous understandings. For example, the understanding of the connections between the spirit world and the physical world at the intersection of old age, death, birth, and infancy help explain “childlike” behaviour and communication with the deceased.

Indigenous participants at an Ontario roundtable on this issue suggested that because people are described as being “closer to the Creator” there may be less stigma associated with mental illness, including dementia, in Ojibwa communities (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007). Other studies have also found a general lack of shame associated with dementia (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Jacklin, Pace, & Warry, Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). However, there was also recognition of dementia and/or Alzheimer’s disease as a biomedical disease process; for example, among the Secwepemc it was reported that the changing perception that dementia is “your dementia” (a disease of white people) has been increasing over the past century (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). Focus group participants in this study agreed to use the term “your dementia” to identify the biomedical disease of dementia.

Despite those who view dementia as normal (or as having been normal prior to colonization), dementia could still be feared by many, and caring for someone with dementia was sometimes viewed as extremely difficult (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). In some cases, communities reported feeling unprepared and poorly equipped to deal with someone in the later stages of the illness (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007). In Ontario, studies found that Indigenous persons with dementia and informal care providers often lacked knowledge about dementia, including information about risk factors, symptoms, progression, and treatments (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Forbes and Richmond2012; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

We found no research reports on understandings of dementia among the Inuit, but did find some limited information on perceptions of aging and conceptions of mental health. One research study in the Northwest Territories with the Inuit community of Holman investigated Inuit conceptions of healthy aging and found linkages to mental and physical capacities (Collings, Reference Collings2001). Continuation of a physically active life on the land was highly regarded among men, and continued social engagement and domestic roles were valued for women. Interestingly, there was no mention of dementia, memory loss, or forgetfulness that emerged from this study. However, there were frequent mentions of “mind changes” being related to aging poorly, which would fall into the categories of apathy and depression that can be related to Alzheimer’s disease. Further, “wisdom”, as related to the role of passing on knowledge, was a highly valued aspect of healthy aging, but not having “wisdom” was never cited as a contributor to “unhealthy aging”. This limited evidence suggests that the primary symptoms of dementia (forgetfulness, memory loss, confusion, inability to recall knowledge) may not be viewed as problematic by Inuit throughout the aging process, but that related symptoms of depression and apathy are viewed as problematic, especially for women. Kirmayer et al. (Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009) cite earlier work (Vallee, Reference Vallee1966), which also described “withdrawal and melancholy” as one of the patterns of mental illness among Inuit, as well as an additional behaviour called quajimaillituq: “a term applied to rabid dogs, and, in this context, conveying the sense ‘he does foolish things and he does not know what he does’” (Kirmayer et al., Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009, p. 312). These categories of behaviours were generally used to describe acute episodes, but there was also recognition that they could become chronic. In their own research, Kirmayer et al. (Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Corin and Boothroy1994), were made aware of isumaqanngtiuq, meaning “he has no mind/brain”, “crazy”, “doesn’t know what is going on around him”, with the literal translation to English being “she/he is without thoughts” (Kirmayer et al., Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Corin and Boothroy1994, p. 31). Kirmayer et al. (Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009) suggest that the same term can be applied to someone who is profoundly intellectually disabled or demented (Kirmayer et al., Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009).

Although little is known about the biomedical construct of Alzheimer’s disease or dementia in Inuit people, the work of Kirmayer et al. (Reference Kirmayer, Fletcher, Watt, Kirmayer and WValaskakis2009) suggests that there is a specific cultural interpretation of symptoms related to dementia for the Inuit, which warrants further work specific to dementia.

Theories of Causation

The most widely held view found to date is that dementia is a natural part of the life cycle. Yet, in most studies, the participants also held alternative views of dementia as a disease caused by external determinants such as Western foods, changes in lifestyle, drug and alcohol use, environmental toxins, and more (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Dwosh, Beattie, Guimond, Lombera and Brief2011; Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012; Pace, Reference Pace2013). One study in northern Minnesota linked dementia with lifestyle, suggesting “…what goes around comes around, and how we live our life will eventually come back to us” (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995). In Ontario, people expressed that dementia has emerged because older adults are not as engaged as they used to be, and discussed that in previous generations they kept busy and had more defined roles, which may have helped to prevent memory loss and other symptoms of cognitive decline (Pace, Reference Pace2013). Those studies that investigated Indigenous peoples’ views of the causes of dementia found that there was generally a much greater emphasis placed on social and environmental factors than on biomedical factors (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Dwosh, Beattie, Guimond, Lombera and Brief2011; Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Pace, Reference Pace2013). Secwepemc participants discussed changes in diet, the transition off the land, chemicals in the food, accidents, alcohol, drugs, age, medications, pollutants, loss of oral cultural traditions, and trauma (residential schools included), creating complex interconnected webs of causation that could include a multitude of the above-mentioned causes (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). Study participants in a remote community in British Columbia with early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease identified by genetic testing, attributed the disease to the environment, changes in diet, industrial pollutants, and alcohol and drug use, in addition to hereditary genetic factors (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Dwosh, Beattie, Guimond, Lombera and Brief2011). One study involving Six Nations of the Grand River Territory and seven rural First Nations communities on Manitoulin Island, Ontario suggests that Indigenous peoples’ explanations of what causes dementia can be categorized into three frameworks: (1) physiological (e.g., genetics, aging, vascular disease, medication side effects, and Parkinson’s disease); (2) psychosocial (e.g., unresolved grief and historical trauma, stress, substance misuse); and (3) Indigenous (e.g. disruptions to land-based and traditional activities) (Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012).

Interpretation of Symptoms

Very little has been reported concerning Indigenous interpretations and understandings of symptoms of dementia. A detailed case study of an American Indian woman described by Henderson and Henderson (Reference Henderson and Henderson2002) demonstrates how an American Indian family living on reserve interprets their mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. For this family, the hallucinations associated with the illness are viewed as a mechanism by which their mother is able to communicate with the “other side”. In this case, her illness was not normalized; rather it was viewed as “supernormal”. The interpretation of symptoms as expressions of culture and as part of the life cycle was also found in Ontario, where some Indigenous research participants expressed great concern when behaviours such as hallucinations were labeled as symptoms of a disease, because caregivers viewed these as visions (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Caregiving

Indigenous caregiving in relation to dementia is only just beginning to be explored in Canadian contexts (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Forbes and Richmond2012; Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, Finkelstein, Gibson and Morgan2013; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). More studies concerning caregiving for older Indigenous people were found coming from the United States (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995; Brown & Gibbons, Reference Brown and Gibbons2008; Chapleski et al., Reference Chapleski, Sobeck and Fisher2003; Graves et al., Reference Graves, Smith, Easley and Kanaqlak2004; Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1996; Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010; John et al., Reference John, Hennessy, Roy, Salvini, Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson1996; John et al., Reference John, Hennessy, Dyeson and Garrett2001) We draw on these studies as well as Canadian studies to provide a more complete overview of the topic.

Informal Caregiving

Informal caregivers in Indigenous communities are reported to find caregiving rewarding, but they also experience stress in the form of anxiety related to the quality of care they are providing (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010), the psychosocial aspects of care, the strains on family relations, and the negative effects on personal well-being (Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1996).

In Indigenous communities, the family is often viewed as the primary or sole provider of care (Buchignani & Armstrong-Esther, Reference Buchignani and Armstrong-Esther1999; Cammer, Reference Cammer2006; Chapleski et al., Reference Chapleski, Sobeck and Fisher2003; Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1996; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; John et al., Reference John, Hennessy, Roy, Salvini, Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson1996). This stems from necessity in some cases, but more often it takes place because of a cultural emphasis on familial interdependence (Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1995), and the cultural values of reciprocity (Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010) and respect (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). However, the dependence on family for the provision of care is sometimes the only option, as many First Nations reserves do not have residential care facilities or trained home care staff that can properly care for people at later stages of dementia (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Studies in the United States among the Pueblo and Northern Plains have found that caregiving is most often provided by females (Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1995; Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010; John et al., Reference John, Hennessy, Dyeson and Garrett2001). One study among Anishinaabe female caregivers found that the eldest child, whether daughter or son, is raised to know that when the time comes to provide care to their elders, it will be their designated role and responsibility (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995). These studies have found that caregiver burden in these communities is exceptionally high, but that the caregivers rarely express any negative emotions. It was reported that the strategy for coping was similar to that of other tribes, which emphasized acceptance and adaptation rather than control or trying to “fix” things or “make them better” (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995; Hennessy & John, Reference Hennessy and John1995), and that caregivers rely heavily on cultural resources such as siblings, extended family, and traditional, spiritual, and religious practices to cope (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995). There is some suggestion as well that cultural values of reciprocity were related to low levels of caregiver stress and strain (Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010), and that Indigenous caregivers feel rewarded in their role because of the development of strong relationships with loved ones (Jervis et al., Reference Jervis, Boland and Fickenscher2010). Such thoughts were echoed in a Canadian study whereby dementia caregivers expressed feelings of frustration, anger, and stress associated with their caregiving responsibilities, but felt committed to and rewarded in their role. Participants in this study attributed their commitment to Indigenous values of respect, reciprocity and love, and reported that they drew strength from their spirituality (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Across both the United States and Canada, Indigenous research has suggested that role conflict, negative feelings, doubt concerning caregiving abilities, and guilt are common burdens experienced by Indigenous caregivers, both when deciding to take on the role, and after the caregiver role has been assumed (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995; John et al., Reference John, Hennessy, Roy, Salvini, Yeo and Gallagher-Thompson1996). Some caregivers relocated and changed their children’s schools (Boss et al., Reference Boss, Kaplan and Gordon1995) or set aside their own careers and education goals in order to fulfill their caregiving duties (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Community Caregiving

An underdeveloped theme that emerged from the Canadian literature is the role of the community in dementia caregiving. Research with a remote First Nation in British Columbia found that the community participated in dementia caregiving in two distinct ways: first, Elders from the community became involved in decision making in cases in which the person with dementia had no family; and second, community members participated in monitoring people with dementia who were known to wander. In the latter case, caregivers sent letters to other community members to alert them to the person’s behaviour (Lombera, Butler, Beattie, & Illes, Reference Lombera, Butler, Beattie and Illes2009). The role of community members in locating the wandering elderly was also mentioned in an Ontario study in which one caregiver explained how everyone in her community knew where she worked and knew that her loved one wandered, so those who located her always knew where to bring her (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Community caregiving was also noted to have potential therapeutic advantages. A caregiver in a remote First Nations community explained that the community is the best place for people with Alzheimer’s disease, as they are surrounded by all of their memory triggers. The caregiver expressed that placing someone with dementia in a hospital setting would result in the loss of those cognitive stimuli (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). Among the Secwepemc, it was suggested that community caregiving is not just therapeutic but also culturally appropriate: “… as part of a community whose members support one another through the life course, an Elder would continue to be supported and to support others while completing their journey through the full circle of life” (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010, p. 342). This group suggested that the words “supporting one another” best reflected the participant’s ideals concerning caregiving for persons with dementia, such as family relationships, holistic health, and community. More explicitly, “supporting one another” is also meant to convey that participants felt that there is a growing disconnect between the vision of the health care system and the vision of the community (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010).

Formal Caregiving

Indigenous grandmothers in Saskatchewan talked about the ‘big change in culture’ that has been occurring in their communities. They discussed the increased pace of life and changing family structures as being related to less community helping and more isolation for elders (Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011). In Ontario, Indigenous people shared how specific historical policies of the federal government, such as the residential school policy, have led to post-traumatic stress in the older Indigenous population, and intergenerational trauma in the younger generations, which greatly affects the ability of families to function in a caregiving role without a healing process (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, Finkelstein, Gibson and Morgan2013). Yet, enabling community and family caregiving is viewed as culturally appropriate whereas long-term care facilities are viewed as a “death sentence” (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007).

Such sentiments about long-term care were echoed in Ontario, where caregivers from rural, remote, and urban Indigenous research sites all expressed a deep aversion to the use of long-term care, sometimes relating this idea directly back to cultural family values (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). Removal from a community to obtain care at a nursing home or hospital was viewed as inappropriate, detrimental to health, and a last resort (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Blake, Thiessen, Finkelstein, Gibson and Morgan2013; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). Others have commented that removal of elders from the community is seen to further disrupt traditional modalities for the passing on of knowledge; that is, preventing the teaching and learning of culture and the passing on of Indigenous knowledge, and has been described as “forced disengagement” (Graves et al., Reference Graves, Smith, Easley and Kanaqlak2004).

These concerns are not unfounded; institutionalization can double the mortality rates for people with dementia (McClendon et al., Reference McClendon, Symth and Neundorfer2006). From the limited studies available, suggestions to strengthen care in the community include improved home care, supporting traditional caregiving values, more culturally congruent and safe care from service providers, and nursing homes that more closely resemble assisted living facilities under the ownership and operation of the tribe or band, which better reflect Indigenous culture, language, and values (Brown & Gibbons, Reference Brown and Gibbons2008; Chapleski et al., Reference Chapleski, Sobeck and Fisher2003; Graves et al., Reference Graves, Smith, Easley and Kanaqlak2004).

Indigenous Medicine

Plant-based remedies and ceremonies are an important aspect of healing from past traumas and medical conditions (Sutherland, Reference Sutherland2007). The inclusion of Indigenous medicine and ceremony in care is a reccurring theme in the literature (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002; Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; Keightley et al., Reference Keightley, King, Jang, White, Colantonio and Minore2011; Pace, Reference Pace2013). These studies suggest that the incorporation of Indigenous medicine is an important part of providing culturally appropriate care and improving outcomes. In Northwestern Ontario, a study that included Alzheimer’s disease in its categorization of “acquired brain injury” found that spirituality and access to Indigenous care were deemed essential (Keightley et al., Reference Keightley, King, Jang, White, Colantonio and Minore2011). It was emphasized that the Ojibwa approach to wellness does not focus on fixing the illness, but rather that wellness is holistic, and improvements in cognitive function can be best accomplished when biomedical health care teams work with Indigenous healers to promote wellness (Keightley et al., Reference Keightley, King, Jang, White, Colantonio and Minore2011).

Limitations

It is unlikely that any search strategy can identify all published knowledge on a given topic. Our search strategy was unlikely to identify any articles in which dementia in Indigenous contexts was incidentally mentioned or in which the mention was not substantial enough to be reflected in the title or keywords. We also believe that our strategy did not adequately capture chapters in edited volumes, because of indexing strategies on the part of publishers.

Because of the limited number of studies concerning culture and dementia in Indigenous populations in Canada, it was necessary to include some US-based studies to inform more substantive discussions. Although we have been transparent in our decision to include these, it is possible that some themes, for example, caregiving, appear more robust than is the case in Canada.

Assessing the state of knowledge concerning how culture influences the experience of dementia in Indigenous populations comes with the strong caveat that Indigenous populations in Canada are diverse. Culture is different among First Nations; First Nations, Inuit, and Métis; among Indigenous communities who are urban, rural, and remote; and among those in the north, south, west, and east. Additionally, in some of the dementia studies we reviewed, researchers found that external pressures resulting from colonialism and increased experiences with, and exposure to, Western biomedical models and Western culture can impact Indigenous frameworks for understanding dementia (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002; Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010; Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012; Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011). That is, each person’s view of dementia reflects biomedical and Western information as well as cultural understandings framed within that person’s own history, circumstances, and context (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002).

Therefore, it is important in considering the consolidated evidence to remember that cultural beliefs and practices presented here are specific to a time and place, and that although they are useful in helping us to understand some common cultural values and conceptualizations concerning dementia in Indigenous peoples, they should not be used to essentialize or romanticize the Indigenous experience with dementia. It is widely recognized now that assigning general cultural attributes or traits to populations comes with many risks to patient care (Botsford et al., Reference Botsford, Clarke and Gibb2011).

Conclusion

Our review revealed that although there have been some recent studies concerning culture and dementia in Indigenous populations in Canada, this remains a relatively unexplored area, with only eight peer-reviewed publications focused on this topic. To date, First Nations communities in British Columbia and Ontario have been involved in Indigenous dementia research. Studies have also included urban populations in Ontario and Saskatchewan, and health service providers in Ontario. All eight of the peer-reviewed publications and all but two of the grey literature contributions were published from 2010 through 2017. Information from a multi-site study in Ontario supplemented by available literature has recently been synthesized into information fact sheets (Indigenous Cognition & Aging Awareness Research Exchange [I-CAARE], 2018; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Blind, Jones, Otowadjiwan and Warry2017), yet the diversity of Indigenous peoples in Canada has yet to be adequately represented in our knowledge base. Overall, we found studies specific to dementia, aging, and caregiving in older Indigenous people in Canada to be rare. The research did not uncover any information specifically concerning dementia in the Inuit population, and, as such, we are only able to hypothesize based on studies concerning aging and mental health. Also, to date we have not located any studies specific to Métis people. The absence of information on the Métis and Inuit populations regarding cognitive health and aging represent important knowledge gaps.

Although the study of dementia among Indigenous populations in Canada is in its infancy, this review revealed several themes relating to how culturally informed frameworks of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias impact the Indigenous experience and understanding of dementia: Indigenous understandings, theories of causation, interpretations of symptoms, caregiving, and Indigenous medicine. Although we do not suggest that these are the only ways that cultural frameworks shape Indigenous experiences, the findings will be useful to health service providers as they begin to respond to the increasing rates of dementia in Indigenous peoples and seek to provide Indigenous-specific dementia care strategies.

The Indigenous determinants of health framework served as a valuable tool for analysis and interpretation. Colonialism as a distal determinant of health was pervasive in these studies. Federal and provincial policies specific to Indigenous populations in Canada shaped the dementia experience for participants in these studies at the distal level by creating differential conditions for Indigenous communities that limit access to their cultural, social, and environmental resources and healing traditions. The outcomes of government policies creating inequitable health, economic, and social systems for Indigenous peoples are realized at an intermediate determinants level at which participants discussed inappropriate and inadequate caregiving resources. At the level of the individual, the participants in these studies shared how the impacts of policies have everyday consequences affecting their belief systems, their family, and their social support systems.

In general, the review revealed that Indigenous peoples hold unique understandings of dementia, which are influenced by an Indigenous cultural framework that people engage with to make sense of the illness. In this view, dementia is often thought of as normal and as a natural part of the “circle of life”, as understood in their teachings that speak of coming “full circle” and “back to the baby stage”. Underlying belief systems about the Indigenous life cycle and Indigenous spirituality support this interpretation. This cultural framework, although reportedly largely intact, has been challenged by Western biomedical models, which consider dementia a physiological disease of the brain (Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012), sometimes leading to the distinction of “your dementia” in reference to Western biomedical constructions of the illness (Hulko et al., Reference Hulko, Camille, Antifeau, Arnouse, Bachynski and Taylor2010). In the articles reviewed, Western biomedical notions of dementia as a disease were usually articulated more prominently in relation to causation as compared with the other themes. For example, Indigenous explanatory models of dementia can be seen to be expanding to include “Western” influences in theories of causation such as vascular factors, diet, and substance misuse (Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012; Lanting et al., Reference Lanting, Crossley, Morgan and Cammer2011). Discussions in the studies reviewed identified concerning disconnection from land and culture, and trauma from residential schools as causes of dementia, which demonstrate how at an individual level Indigenous people connect the distal determinants of health to their everyday dementia experiences.

The review also uncovered some of the ways that culture permeates experiences of symptoms of dementia, particularly visions (Henderson & Henderson, Reference Henderson and Henderson2002; Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012). In these cases, symptoms commonly known as hallucinations were understood as visions and as gifts that individuals have access to as they sit closer to the Creator at this point in their life cycle. This discord between Indigenous and biomedical understandings of the cause of this phenomenon was noted as a source of conflict at the patient level (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015). Overall, culturally grounded understandings were reported to be beneficial in reducing stigma and promoting familial and community caregiving. Respecting these views will be an important aspect of the development of culturally safe dementia care and the overall decolonization of health care (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015; Jacklin & Warry, Reference Jacklin and Warry2012).

Caregiving is a theme that is just beginning to be explored in Canada, with a much longer research record in the United States. Taken together, the evidence suggests that there is a strong desire to age in place (in one’s home community), even when physical or cognitive limitations are present. All of the caregiving literature suggests that formal institutionalized caregiving is viewed as problematic by many Indigenous people. Institutions are viewed as a mechanism by which the transmission of knowledge between generations in the community is interrupted, and elders’ important roles in the community are undermined, especially when institutions are located outside of the community. Although there are significant medical and social challenges for older Indigenous populations, the studies we reviewed suggest that informal caregivers in Indigenous communities often view their roles positively and accept responsibility with few questions. Cultural values play a large role in sustaining informal and community caregiving in these communities. Historical and contemporary government policies and the changing way of life in Indigenous communities figured prominently in the caregiving literature reviewed. Although culture was a positive force in sustaining community-based caregiving models, it was clear from the participants in these studies that past policies such as residential schools and the Sixties Scoop created familial disruptions and, in some cases, unhealthy home environments. Particular participants described their conversion of these challenges into positive caregiving outcomes (Jacklin et al., Reference Jacklin, Pace and Warry2015).

Very little was revealed about the potential role of Indigenous medicine and Indigenous approaches to care for dementia. Across studies, participants referenced Indigenous understandings of health as related to medicines and healing, but nothing has yet been reported that would provide specific information on how Indigenous medicine could be applied to dementia. Although perhaps not surprising, there may be much to learn from investigations in this area that would help support culturally safe dementia care for Indigenous peoples.

There are recent “calls to action” resulting from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada findings (The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015). Many of the actions are related to the provision of appropriate, safe, and equitable health services for Indigenous peoples in Canada. This review suggests that Indigenous culture has an important and central role in shaping understandings of dementia as well as responses to the illness. It provides a means to understand the illness and its symptoms, and to shape how loved ones and communities respond. What has been published to date suggests that dementia is an area that would greatly benefit from cultural safety training for health care practitioners. There is certainly room for practitioners to reflect on any potential bias that they may carry during health care interactions, and to consider opportunities that they have in their practice to respect and incorporate Indigenous views of the illness. The Indigenous dementia fact sheets found at www.I-CAARE.ca/factsheets are currently the only tools available to guide providers and those affected in the Indigenous dementia care journey.

As rates of dementia continue to increase in Indigenous populations, individuals, communities, and health and service providers will need information concerning the patient and caregiver experiences in order to formulate appropriate responses and services. Although not reviewed in this article, it is not difficult to speculate that if culture is shaping Indigenous perspectives on cause, symptoms, and caregiving, culture will equally influence prevention and intervention. Given the growing disparity in the prevalence of dementia in Indigenous populations in Canada and abroad, it is imperative that there are substantial investments in research concerning Indigenous patient and family experiences from diverse regions of the country. This knowledge is fundamental to the provision of appropriate, effective, and safe dementia care for Indigenous populations.