Introduction

In Canada, approximately 7 per cent of older persons over the age of 65 years have some form of dementia, with around 76,000 new cases diagnosed each year (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2017). Older persons with dementia have twice as many co-morbid conditions as those without dementia and are at increased risk for other health issues, including falls, infections, and stroke (Poblador-Plou et al., Reference Poblador-Plou, Calderón-Larraňaga, Marta-Moreno, Hancco-Saavedra, Sicras-Mainar, Soljak and Prados-Torres2014; World Health Organization, 2019). Indeed, research has shown that persons with dementia are more likely than those without to be admitted for emergency hospitalization (Canadian Institute of Health Information, 2018; LaMantia, Stump, Messina, Miller, & Callahan, Reference LaMantia, Stump, Messina, Miller and Callahan2016; Sommerlad et al., Reference Sommerlad, Perera, Mueller, Singh-Manoux, Lewis, Stewart and Livingston2019). With increasing numbers of persons living with dementia and higher rates of hospitalization, it is necessary to ensure they receive appropriate and effective acute care. In this Policy and Practice Note, we present our international, collaborative work to bring a dementia education program for acute health care providers (HCPs) to Canada. Herein we present: (a) an overview of the program; (b) results from a national environmental scan; (c) key informant interviews; and (d) findings from a two-day meeting to begin initial work towards adaptation.

Research suggests that acute care environments are often harmful for persons with dementia (Dewing & Dijk, Reference Dewing and Dijk2016). Commonly identified issues include lack of privacy, noise, overcrowding, loss of independence, difficulty in wayfinding, boredom and lack of meaningful activities, unmet needs, and bed/ward moves (Clissett, Porock, Harwood, & Gladman, Reference Clissett, Porock, Harwood and Gladman2013; Digby & Bloomer, Reference Digby and Bloomer2014; Hung et al., Reference Hung, Phinney, Chaudhury, Rodney, Tabamo and Bohl2017; Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman, & Harwood, Reference Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman and Harwood2012; Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth, & Beattie, Reference Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth and Beattie2016; Parke et al., Reference Parke, Boltz, Hunter, Chambers, Wolf-Ostermann, Adi, Feldman and Gutman2017; Prato, Lindley, Boyles, Robinson, & Abley, Reference Prato, Lindley, Boyles, Robinson and Abley2019). Persons with dementia may also feel devalued and disempowered when acute HCPs do not include them in conversations or respect their wishes for care (Hung et al., Reference Hung, Phinney, Chaudhury, Rodney, Tabamo and Bohl2017). Families also report unmet expectations regarding personalized care and the maintenance of their relative’s dignity, physical comfort, privacy, identity, and safety (Jurgens et al., Reference Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman and Harwood2012). Acute HCPs often appear focused on medical treatment and task-oriented care while not necessarily meeting the person’s fundamental care and broader psychosocial needs (Jurgens et al., Reference Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman and Harwood2012; Moyle et al., Reference Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth and Beattie2016). In addition to the well-being of the person with dementia, families have identified communication with acute HCPs as a major issue (Jurgens et al., Reference Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman and Harwood2012; Moyle et al., Reference Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth and Beattie2016).

Acute HCPs describe many of the same issues, recognizing and aiming to minimize the disorientation that persons with dementia often experience, and acute HCPs work to create a safe environment, establish positive relationships, and attempt to initiate activity routines (Hynninen, Saarnio, & Isola, Reference Hynninen, Saarnio and Isola2014; Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Faul, Saxer, Burgstaller, Kamleitner and Mayer2018). Prato et al. (Reference Prato, Lindley, Boyles, Robinson and Abley2019) reported that acute HCPs felt it was important to practise person-centred care and empower persons with dementia, yet this did not always occur.

The busy pace of wards and understaffing affects the amount of time that acute HCPs can spend interacting with persons with dementia, who are perceived to require more time and effort for care than other persons (Coffey et al., Reference Coffey, Tyrrell, Buckley, Manning, Browne, Barrett and Timmons2014; Houghton, Murphy, Brooker, & Casey, Reference Houghton, Murphy, Brooker and Casey2016; Hynninen et al., Reference Hynninen, Saarnio and Isola2014; Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Faul, Saxer, Burgstaller, Kamleitner and Mayer2018). Acute HCPs also report inadequate dementia care training, resulting in reduced confidence and capability to effectively care for persons with dementia (Coffey et al., Reference Coffey, Tyrrell, Buckley, Manning, Browne, Barrett and Timmons2014; Cowell, Reference Cowell2010; Dewing & Djik, Reference Dewing and Dijk2016; Hynninen et al., Reference Hynninen, Saarnio and Isola2014; Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Faul, Saxer, Burgstaller, Kamleitner and Mayer2018).

Given these concerns, there have been calls for enhanced dementia education and development of standards and core competencies for acute HCPs (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, 2019; Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, Murphy, Brooker and Casey2016; Hynninen et al., Reference Hynninen, Saarnio and Isola2014). Indeed, improving dementia care is an identified priority for Canada (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2019) and is reinforced by Canada’s National Dementia Strategy principles (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Moreover, there is a clear need for efforts to go beyond educating individuals and enable positive changes at unit, department, and organizational levels (Moyle, Borbasi, Wallis, Olorenshaw, & Gracia, Reference Moyle, Borbasi, Wallis, Olorenshaw and Gracia2010; Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Faul, Saxer, Burgstaller, Kamleitner and Mayer2018).

Acute HCPs have access to few effective dementia education programs (Gkioka et al., Reference Gkioka, Schneider, Kruse, Tsolaki, Moraitou and Teichmann2020). One program in Canada described acute care staff’s experience with Gentle Persuasive Approaches (GPA), a program developed for long-term care staff to improve hands-on dementia care (Gkioka et al., Reference Gkioka, Schneider, Kruse, Tsolaki, Moraitou and Teichmann2020; Hung et al. Reference Hung, Son and Hung2019). GPA was evaluated in an acute care hospital in Ontario and had a positive effect on staff self-efficacy; however, the impact on patient health was not assessed (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Gillies, Coker, Pizzacalla, Montemuro, Suva and McLelland2016). While important, the GPA program does not involve the sufficient training intensity that Gkioka et al. (Reference Gkioka, Schneider, Kruse, Tsolaki, Moraitou and Teichmann2020) suggest is necessary to make changes at the organizational level in culture and practice within acute care settings. Moreover, the GPA was not designed for acute care settings. To the best of our knowledge, no extensive dementia education program, specifically for acute HCPs, exists in Canada, despite the need for such a program.

A dementia education program designed specifically for acute HCPs that has evidence for effectiveness is delivered in Scotland. The Scottish National Dementia Champions Programme (herein referred to as the Programme) equips acute HCPs with the knowledge, values, and skills needed to provide high-quality dementia care and support them to lead change in their care areas (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Waugh, Henderson, Sharp, Brown, Oliver and Marland2014). Evaluation has shown that the Programme has a measurable impact on participants’ knowledge of dementia, approaches to care, and confidence in their ability to achieve the Programme’s learning outcomes (Jack-Waugh et al., Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018). A Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland report (2018) highlighted the clear benefits of additional access to resources for other staff, persons with dementia, and carers. The Programme was developed to provide enhanced education that considers the complex systems that exist in the acute care context. Surr et al.’s (Reference Surr, Gates, Irving, Oyebode, Smith, Parveen, Drury and Dennison2017) systematic review identified several criteria of effective dementia education (e.g., relevant to participants’ role, encompasses in-person participation, taught by an experienced facilitator, has greater than eight hours of sessions); the Programme includes all of them. Given its rigorous development and focus on both individual education and broader practice/organizational change, the Programme could potentially address dementia education gaps for acute HCPs in Canada.

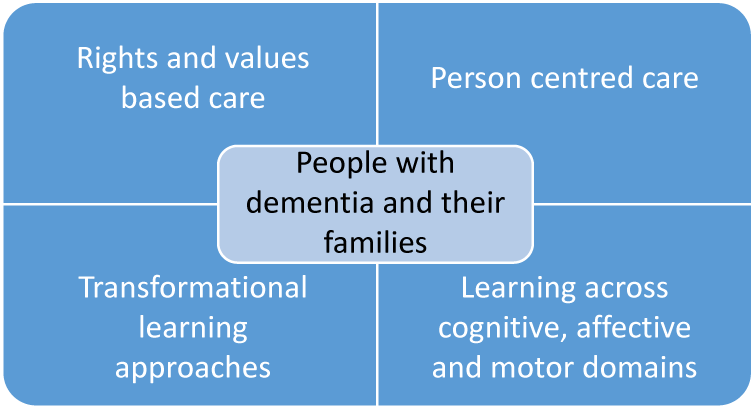

The Programme was commissioned as part of Scotland’s first dementia strategy, in response to the poor acute care that persons with dementia were experiencing (Alzheimer’s Society, 2009; Elvish et al., Reference Elvish, Burrow, Cawley, Harney, Pilling, Gregory and Keady2018; The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011). Funded by the Scottish Government in collaboration with the National Health Service Education for Scotland, and the Scottish Social Services Council, the Programme has been running since 2011. The University of the West of Scotland led the design and delivery of the Programme in partnership with Alzheimer Scotland. The Programme’s underlying pedagogical approach is described by Jack-Waugh et al. (Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018) and illustrated in Figure 1. Human rights, values-based care, and an understanding of the social model of disability (Durrell, Reference Durell2014) form the Programme’s theoretical spine (Jack-Waugh et al., Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018). Its pedagogy is informed by transformative learning theory, working with the affective (heart), cognitive (head), and psychomotor (hands) domains (Singleton, Reference Singleton2015). A collaborative approach to delivery has been central to enacting the Programme’s ethos; persons with dementia, family carers, and health and social care practitioners are all part of the education team. The Programme is grounded in Kitwood’s (Reference Kitwood1997) theoretical perspective of person-centred care for persons with dementia. The principles of valuing persons with dementia and their carers, treating them as individuals, seeing the world from the person with dementia’s perspective, and creating a positive social environment that promotes their well-being (Brooker, Reference Brooker2003) are all foundational to the Programme’s goals and teachings.

Figure 1. Pedagogy of the Dementia Champions Programme.

(Source: Jack-Waugh et al., Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018)

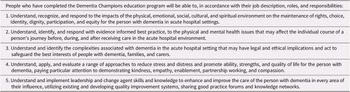

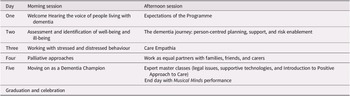

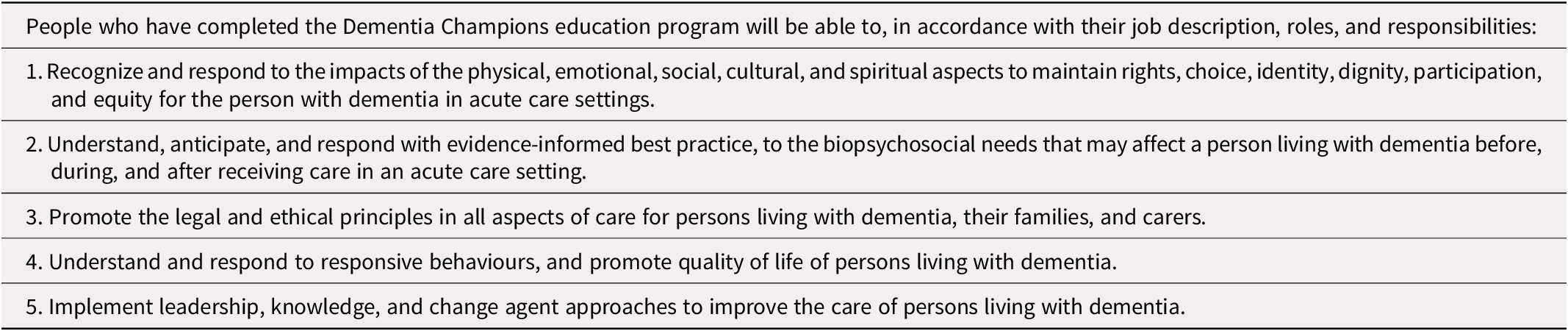

The Programme’s main objective is to provide enhanced dementia care education to HCPs, supporting them to lead change in acute care settings that will improve care for persons with dementia and their families. The six-month program includes a blended educational program with pre- and post-reading for the five in-person study days and half-day community placement; three written assignments; and development of a collaborative change plan to improve dementia care in their care setting. In sum, the Programme’s unique elements include: (a) recognizing the challenges in acute care settings; (b) using a rights-based approach; (c) having persons living with dementia as an integral part of the teaching team; (d) partnering with family carers; and (e) disseminating the champions’ developed activities to benefit their colleagues. The Programme’s learning outcomes and topics covered in the teaching sessions are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1. Dementia Champions Programme learning outcomes

(Source: Banks et al., Reference Banks, Waugh, Henderson, Sharp, Brown, Oliver and Marland2014)

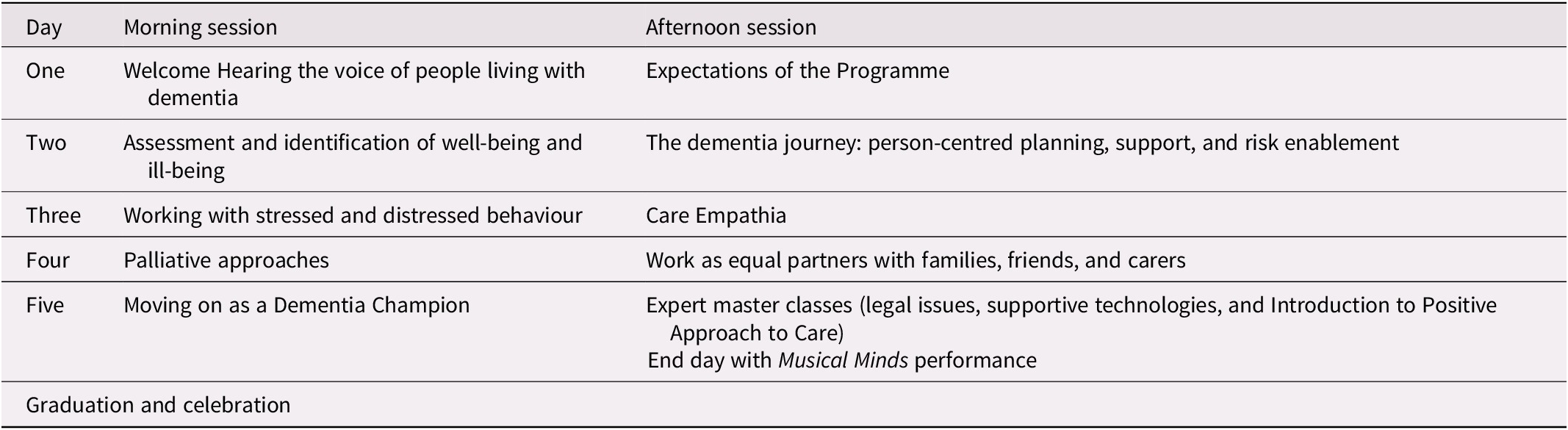

Table 2. Dementia Champions Programme sessions

Source: Banks et al., Reference Banks, Waugh, Henderson, Sharp, Brown, Oliver and Marland2014.

To date, over 1,000 qualified health and social care professionals have completed the Programme in Scotland. Approximately 70 per cent of participants are qualified nurses; other participants include allied health professionals (e.g., occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, podiatrists, dietitians), nurse educators, managers (discharge and patient flow), and hospital social workers. There is evidence that some champions have made demonstrable practice improvement, such as implementing “Getting to Know Me” (Alzheimer Scotland, 2015), to provide more person-centred care, improving pharmaceutical support, environmental design and change, increased partnership with families, delirium prevention, personal music, a bedside vascular service, creation of quiet spaces and gardens, activity boxes, and dementia cafés (Jack-Waugh et al., Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018). Developing examples of some of the Dementia Champions’ actions can be accessed through #oneweething and the Blog: https://letstalkaboutdementia.wordpress.com/.

Adapting the Programme for Canada

Providing comprehensive dementia care education to acute HCPs will increase their capacity to provide optimal care to persons with dementia, which is one of the priorities identified in Canada’s National Dementia Strategy (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). The Programme’s focus on individual dementia care education together with a broader practice and system change is unique. This program was chosen for adaptation in Canada because of these focuses, its grounding in best practices, its success in Scotland, and the generosity of our Scottish colleagues in sharing their knowledge throughout the adaptation process. The fit between the Programme and philosophical goals of dementia care in Canada, specifically the strong grounding in person-centred care and inclusion of persons with dementia and carers as peer educators (Jack-Waugh, Reference Jack-Waugh, Ritchie and MacRae2018), are also fundamentally important.

Co-production is embedded within our work via Hawkins et al.’s (Reference Hawkins, Madden, Fletcher, Midgley, Grant, Cox and White2017) framework for the co-production of an intervention entailing three stages: (a) evidence review and stakeholder consultation; (b) co-production of intervention content; and (c) prototyping the new intervention. This Policy and Practice Note presents the first stage of evidence review and stakeholder consultation, which included three steps: (1) an environmental scan to examine existing dementia education for Canadian acute HCPs; (2) key informant interviews with two carers and one person with dementia about their experiences of acute care and issues needing attention, to hear from those with recent lived experience; and (3) a planning meeting with various experts – including our Scottish collaborators (AJW and RM) – to establish program principles, priorities, learning outcomes, pedagogical approaches, and content for a Canadian program. These steps (along with a literature review) constitute an evidence review and stakeholder consultation, laying the groundwork for co-producing intervention content. The process and outcomes of each step are described below. Ethical approval for each step was received from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Saskatchewan.

Adaptation Activities and Findings

Environmental Scan of Current Canadian Programming

The purpose of the environmental scan was to examine the literature and publicly available information (Graham, Evitts, & Thomas-MacLean, Reference Graham, Evitts and Thomas-MacLean2008) guided by the work of Choo (Reference Choo1999) to identify currently available Canadian dementia education programs for acute HCPs. Strengths, limitations, and gaps of the programs were also considered.

Methods

Data for the environmental scan (Choo, Reference Choo1999; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Evitts and Thomas-MacLean2008) included correspondence (n = 4 telephone interviews, n = 4 e-mail communications) with Alzheimer Society staff from across Canada between November 2019 and February 2020. Since most dementia education occurs either directly or in partnership with Provincial/Territorial Alzheimer Societies, they were considered the key experts to consult. Alzheimer Society offices were contacted by e-mail, and participating staff were asked to provide their perspectives on challenges/needs faced by persons with dementia when in acute care. They were also asked to identify any existing dementia education program for Canadian acute HCPs offered by their organization or others, and describe what they thought would be essential to include in such a program. Data from the staff were transcribed and analysed for salient content using a thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Other data on existing programming were obtained via a Google search conducted between September 2019 and January 2020, using the terms “Canada”, “dementia education”, “workshops”, and/or “online/webinar”.

Findings

The environmental scan’s findings include: (a) challenges, needs, and priorities of persons with dementia in acute care shared by Alzheimer Society staff; and (b) current education programs for acute HCPs on offer in Canada as identified by staff and the Google search, and components/elements that should be included in an education program for acute HCPs (Surr et al., Reference Surr, Gates, Irving, Oyebode, Smith, Parveen, Drury and Dennison2017).

Challenges, needs, and priorities of persons with dementia in acute care. Alzheimer Society staff perceived persons with dementia and their carers as facing stigma, disabling built environments, limited HCP understanding and knowledge of dementia, and a lack of person-centred care. Staff felt persons with dementia were misunderstood by acute HCPs, “who often have stereotypic and stigmatized images in their heads of what a person with dementia looks like” (telephone interview). By identifying as a person with dementia, a person may be ignored or communicated to differently, and unrelated symptoms may be assumed to be “just dementia, this is nothing more” (telephone interview). Staff also felt that persons with dementia and their carers may not disclose a dementia diagnosis to acute HCPs to avoid misdiagnosis and mismanagement of illness or pain.

Staff-cited gaps in acute HCPs’ dementia-related knowledge included lack of systematic protocols for supporting persons with dementia in acute care, absence of training to identify persons with dementia and their symptoms, lack of clarity around effective communication with persons with dementia, and inappropriate use of physical and chemical restraints. For example, staff shared stories such as HCPs “using straps to tie [a person] to the bed, which is very alarming to see a family member tied down like that, and of course resorting to medications to calm [a person with dementia] down” (telephone interview) instead of trying to determine and address their needs. A lack of person-centred approaches to care, with the predominance of a general one size fits all approach, insufficient continuity of care, and inadequate communication between acute HCPs and families were identified. The challenges and unmet needs staff identified are consistent with the reviewed literature, suggesting these issues remain in Canadian acute care environments.

Staff identified elements of acute care that could be improved to address the above issues. They emphasized that care should be provided by HCPs who have received enhanced experiential simulated learning of dementia, because persons with dementia “should be cared for by a team who has received the proper education/training” (e-mail communication). They stressed the need for acute HCPs to be educated about dementia (e.g., types, diagnosis, treatments, and symptoms). Staff felt that acute HCPs should know how to: (a) support persons with dementia; (b) provide person-centred care; (c) connect families with dementia support services; (d) work in partnership with families/carers; and (e) improve communication about the person’s needs, likes, and abilities. Staff also felt that preparing persons with dementia and carers for acute care could be helpful. For example, carers could create a written summary with the person with dementia about their most critical health care needs, current abilities, and likes and dislikes that could be brought into acute care and shared with HCPs. Staff identified the Alzheimer Society’s First Link as another resource that could help prepare families for acute care settings (McAiney, Hillier, Stolee, Harvey, & Michael, Reference McAiney, Hillier, Stolee, Harvey and Michael2012).

Lastly, staff felt built environments should be modified to be more enabling and dementia-friendly. Acute care environments by design are clinical spaces, often very bright with shiny hard surfaces, noisy, and difficult to navigate. Without adaptations for persons with dementia, environments can be both distressing and disabling. Staff identified several potential modifications, including clear wayfinding signage, lighting to improve visibility and reduce glare, access to quiet spaces/rooms, consistent use of visible staff name tags, and standard uniforms “that make staff recognizable” (telephone interview). Overall, staff felt that improving acute care experiences for persons with dementia and their carers would require a significant culture shift within organizations.

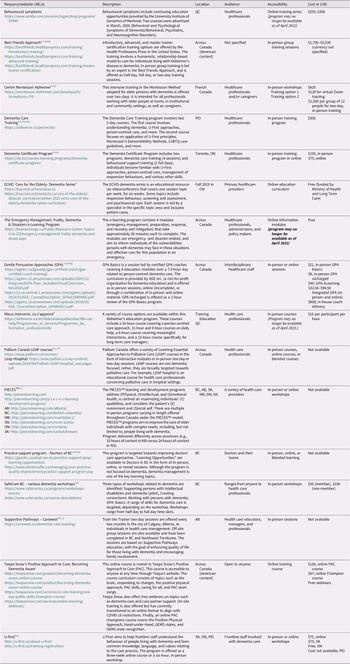

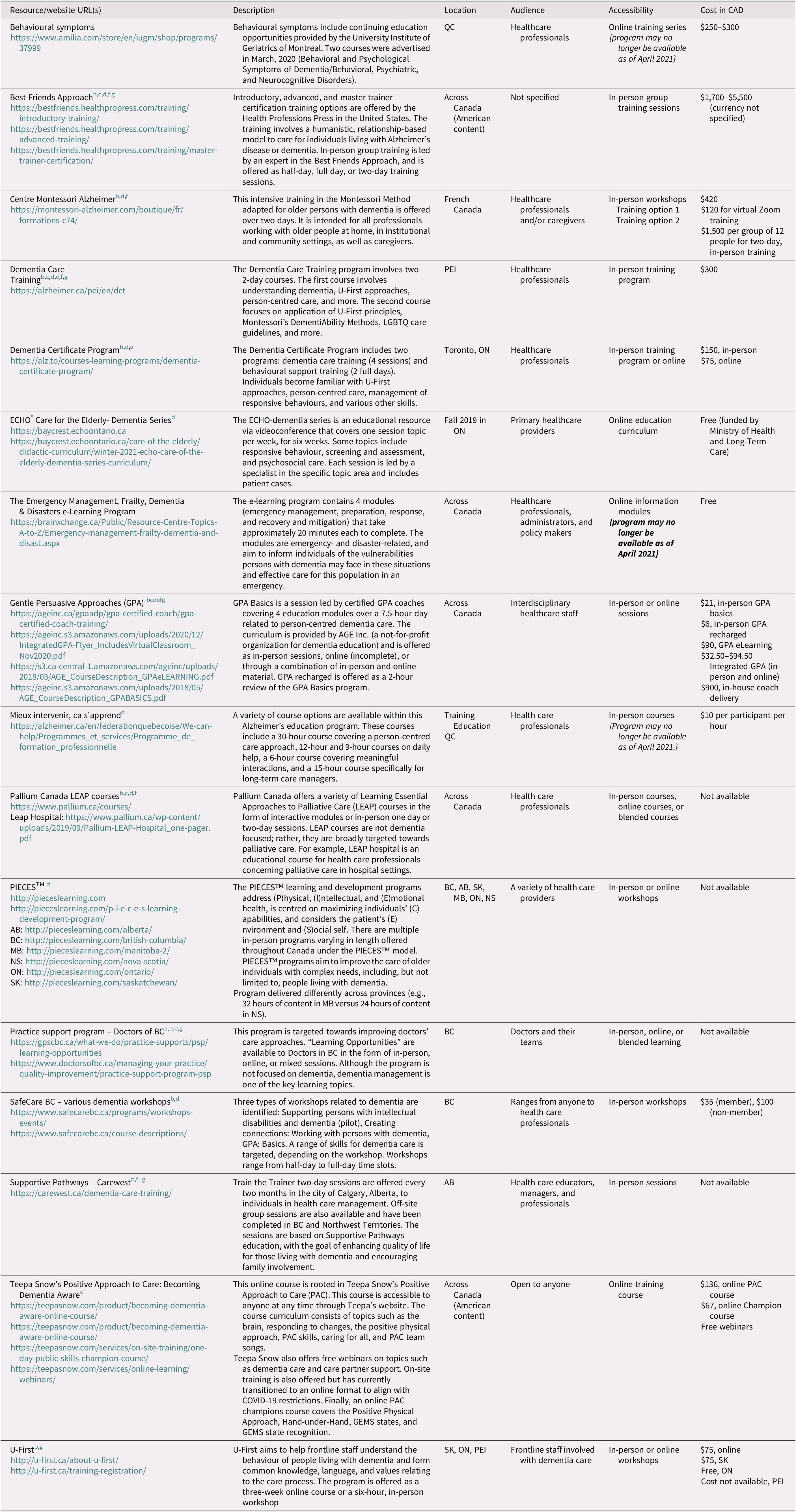

Current education programs for acute HCPs. We identified 16 educational programs in Canada that incorporate dementia education accessible to acute HCPs. Table 3 describes the location, audience, curricula, accessibility, and cost of these programs. Dementia care was the specific focus of six programs, although all included a dementia-related component. The other programs focused more broadly on persons living with dementia, psychiatric, and cognitive disorders; those in palliative care; and older persons in general. The target audience of most programs was HCPs working in a range of settings; no program was specifically focused on acute HCPs. Six program websites did not provide specific information about dementia-related curricula, and four programs could be accessed online only. Of the seven program websites that included curricula, commonly covered topics were screening, diagnosis, communication, and brain and behaviour changes. Less often, curricula included topics such as self-protection strategies for HCPs, strategies for risk situations, action planning, and general information on aging. Some of the components of effective dementia education were clearly part of identified programs (Surr et al., Reference Surr, Gates, Irving, Oyebode, Smith, Parveen, Drury and Dennison2017): 10/16 programs offered face-to-face courses (3 did not specify), 10 included course options that had a total duration of eight hours (3 did not specify), 6 provided individuals with a structured tool (10 did not specify), 6 included interactive learning (7 did not specify), 5 were delivered by an experienced facilitator (10 did not specify), 4 supported the application of learning in practice (6 did not specify), and 1 noted that programs were oriented to be relevant to the learner (15 did not specify).

Table 3. Canadian resources for dementia education

a Content relevant to participant’s role.

b Face-to-face instruction.

c Experienced facilitator.

d Content > 8 hours.

e Apply learning to practice.

f Structured guide.

g Interactive learning.

Findings from this environmental scan suggest that dementia education for Canadian acute HCPs is limited and piece-meal across the country, and not geared specifically towards acute care. Moreover, while some programs are grounded in concepts of person-centred care and include a focus on understanding persons with dementia and their needs, none address the concern that education of learners should tackle broader shifts in practices, policies, and organizational cultures within acute care (Moyle et al., Reference Moyle, Borbasi, Wallis, Olorenshaw and Gracia2010; Pinkert et al., Reference Pinkert, Faul, Saxer, Burgstaller, Kamleitner and Mayer2018). This illustrates the need for a Canadian program that supports acute HCPs to both increase their knowledge of dementia, and lead and implement change on a broader scale (Surr et al., Reference Surr, Gates, Irving, Oyebode, Smith, Parveen, Drury and Dennison2017).

Lived Experience Interviews

The purpose of the key informant interviews was to provide a means for planning meeting participants to hear the experiences of persons with dementia and carers, and identify any additional issues that may be unique and important to address in the Canadian dementia education program for acute HCPs.

Methods

Semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with three key informants (one man living with dementia and his wife carer, and an additional woman carer) recruited through the Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan, who had experienced an acute care admission within the last 12 months. Given that the purpose of our key informant interviews was to hear about recent acute care experiences (not to provide information about acute care experiences that is generalizable to all persons with dementia and carers), the small number of participants was deemed sufficient. Informants were asked questions like: “Can you please describe your recent experience in the hospital?” “What do you think needs to change to better support people with dementia and family carers who are accessing hospital care?” “What is most important for health care providers working in hospitals to know about what it is like to be a person with dementia or a family carer of a person with dementia going to the hospital for care?” Interviews were held in informants’ homes and were audio-recorded then transcribed. Thematic analysis was conducted to identify key elements of informants’ experiences (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Analysis involved an iterative process (undertaken by SP and KH), whereby transcripts were read and re-read for key aspects of the informants’ experiences; then coding was performed to capture key elements in the data, developing and refining themes in collaboration with AJW to highlight the salient elements of the informants’ experiences.

Findings

Key informants highlighted the importance of three things: the need for frequent and effective communication from acute HCPs, the nature of acute care environments, and the need for person- and family-centred care. First, informants spoke at length about the significance of regular contact with and communication from providers. A communication vacuum was the biggest problem in their acute care experiences; they described missed opportunities to connect with doctors and lack of sufficient communication from nurses:

I never met the doctor that was supposed to be looking after him. The nurses wouldn’t tell me a lot. I wasn’t happy with it, but he was being looked after and that was the most important thing to me… I just thought there was a lack of communication. I’d want some information and I didn’t get it. ‘He’s doing fine’ or something like that. I wanted to know exactly. (Carer #1)

Carers desired clear communication about how the person was doing when they were not there, medical information from supervising doctors, and chart updates. They wanted this communication on a regular and ongoing basis and did not want to have to “chase down” acute HCPs to get it – an often unsuccessful endeavour. Communication was considered crucial because the symptoms of dementia made it difficult for the person to remember and effectively communicate details to their carers.

It was also important that communication be concrete, effective, and accessible. For example, our informant with dementia identified the value of having printed information to supplement verbal communication: Actually giving documents or a note of something, saying this is what we have discussed. So it doesn’t just go in one ear and out the other, because I have a hard time retaining things sometimes. One carer noted that she also appreciated when acute HCPs were patient with her loved ones when they did not understand or forgot information.

Secondly, the acute care experience was improved when the setting was “homey” and had windows so the person with dementia could look outside. Crowded, dingy, and depressing environments were problematic, as were lighting and noise:

I find that I need the calm and you’re in a ward with a whole bunch of other people… You’re just having a nap and more visitors come in. That really gets me going. It’s a hectic environment to be in… I find it stressful. (Person with dementia)

One carer suggested that not having a quiet space, sharing a room with other patients, and disrupted sleep exacerbate emotions like anxiety, agitation, fear, and uncertainty that persons with dementia may experience in acute care. She suggested this should be mitigated by more attention to the allocation of persons with dementia to particular spaces, and a more personalized approach to care.

Finally, it was clear that a person- and family-centred approach to care was important. Informants appreciated opportunities for personal connection with acute HCPs wherein they felt valued: That really does go a long way when you’re seeing the same people, and they know you, and you have the sense that they know you… I think connection is really, really important (Carer #2). Feeling a connection was closely tied to communication and not feeling like information was withheld, as well as interactions where HCPs were patient, kind, and understanding. It was important to carers to be involved in the care of the person with dementia via communication with acute HCPs, so that care was family-centred. Although informants were satisfied with the medical care persons with dementia received, one of the carers was distressed by instances where her husband’s fundamental needs and human rights were not met: He used to say he had to go to the bathroom, they’d say ‘well he has to wait until one o’clock, he can’t go because it takes two of us to sit him in the bathroom’, I always found that hard (Carer #1). Other issues were the need for comfort in the acute care environment, stability (not being repeatedly moved to different environments), and support maintaining mobility.

The experiences of informants were consistent with the broader literature (e.g., Clisset et al., Reference Clissett, Porock, Harwood and Gladman2013; Hung et al., Reference Hung, Phinney, Chaudhury, Rodney, Tabamo and Bohl2017; Jurgens et al., Reference Jurgens, Clissett, Gladman and Harwood2012; Moyle et al., Reference Moyle, Bramble, Bauer, Smyth and Beattie2016). In particular, the importance of regular and appropriate communication that is not only effective in conveying information but also engenders a person- and family-centred approach was highlighted. Hearing informants’ experiences reaffirm these critical aspects for education and change in practice.

Planning Meeting

The purpose of the planning meeting, held over two days in February 2020, was to bring experts (n = 19, academics from across Canada, community stakeholders from the Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan and older adult community services, acute care clinicians such as nurses and a psychologist, and a couple living with dementia) together to collaborate on how to adapt the Dementia Champions Programme to the Canadian context. Those who could not attend in-person (n = 3) participated via Webex. The objectives were to: (a) establish Canadian priorities for dementia education; and (b) use these priorities to adapt the overarching learning outcomes and individual sessions of the Programme. SP, AJW, and RM collated pre-meeting information to share with the participants, including a summary of the environmental scan described above, the executive summary of Canada’s National Dementia Strategy, and a summary of the Programme objectives. Detailed agendas were created for each day to guide and inform the meeting process.

Day one

Priorities for acute HCP dementia education in Canada were established using an adapted Nominal Technique (American Society for Quality, 2019). First, participants watched a video (created by KH and SH) that shared our key informants’ experiences in acute care. This was important to ensure their experiences and issues were foreground in discussions of priorities, and to reflect the importance of involving persons with dementia and carers as peer-educators.

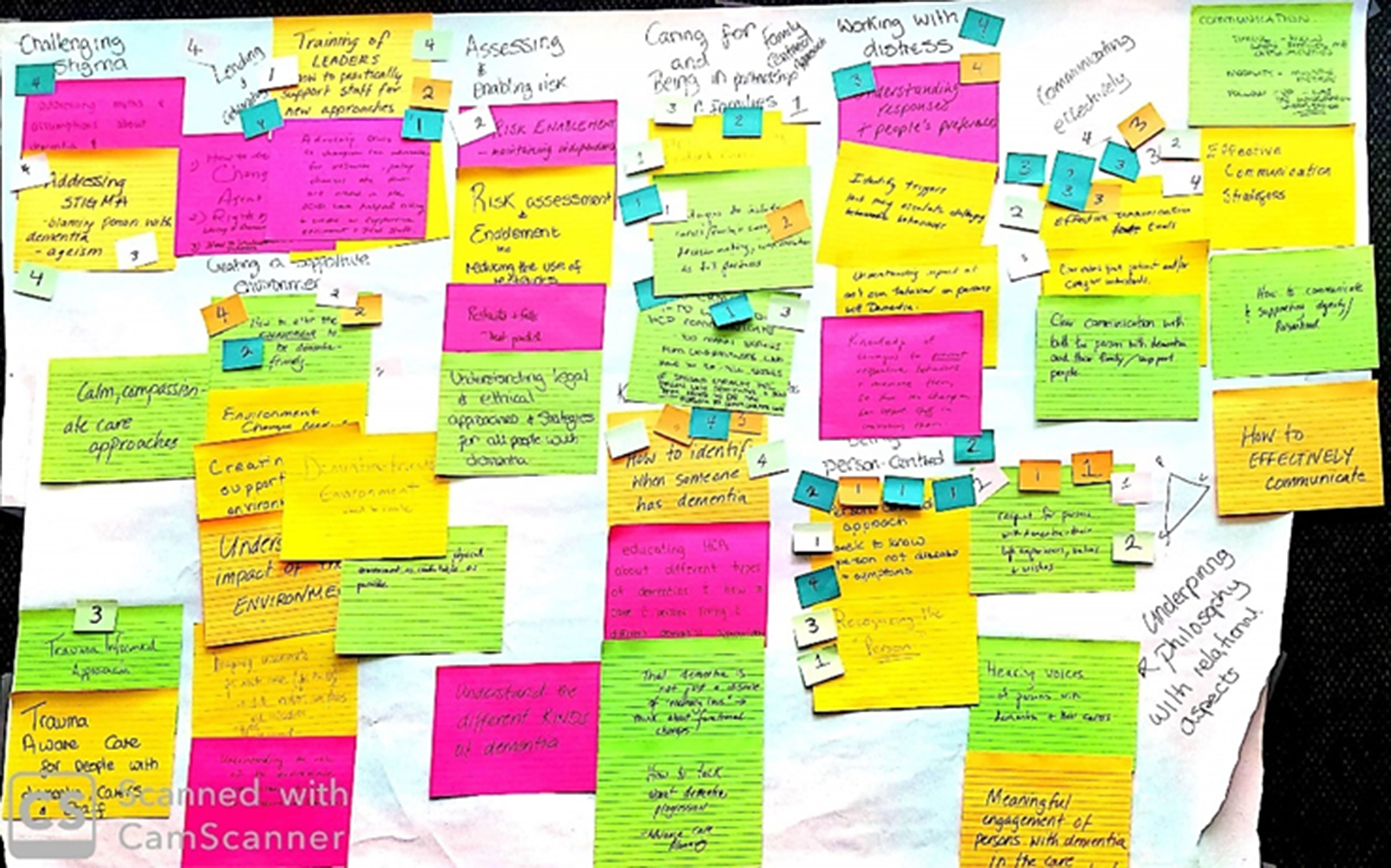

The group then deliberated and voted on main priorities. Participants were asked, “In light of your dementia research, education, and/or practice experience, if you were to design a dementia education programme for professional healthcare staff working in acute care settings what would your top three priorities need to include?” Participants wrote their priorities on sticky notes and added them to a blank wall chart for the group to view (those participating by Webex e-mailed their priorities to be added). Priorities were thematically grouped on the wall chart by two collaborators (SP and AJW). Participants discussed these themed priorities then voted (via sticky notes) for the three they believed were most important. Voting and subsequent discussion showed that participants felt a person- and family-centred approach was crucial as a philosophy for care and should ground all other priorities. With that established, another round of voting was held that established the following key priorities: (a) communicating effectively, (b) working with responsive behaviours, (c) understanding different dementias, (d) creating supportive environments, and (e) identifying leadership qualities that lead to advocacy (Figure 2 captures this process of establishing these priorities).

Figure 2. Canadian priorities.

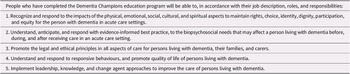

Once Canadian priorities were drafted, we heard from WD about how to effectively adapt interventions; this was important so the group recognized the need to maintain the fidelity of the Programme while reflecting the principles of Canada’s National Dementia Strategy, health care system, professional education, and values. We continued with a presentation on the Programme’s five overarching learning outcomes (AJW). We then used an adapted World Café (The World Café, 2020) approach to adapt the outcomes to a Canadian context, bearing in mind the identified Canadian priorities. Five flipcharts, each listing individual outcomes, were placed on five tables. Participants moved about the room (in five-minute intervals) between the flipcharts to discuss written feedback on adapting the Scottish learning outcomes. The adapted outcomes for Canada can be viewed in Table 4. The Canadian learning outcomes incorporate differing action words (e.g., instead of “understand and identify” we used “promote” for learning outcome #3), yet align with Scottish learning outcomes as our identified priorities were largely reflected in the Scottish program. We refined the learning outcomes and incorporated language common to Canada (e.g., learning outcome #4 “responsive behaviours”). The day ended with a participatory example of simulated experiential learning of one pedagogical approach used in the Programme, lead by RM. These activities sensitized participants to the work ahead in adapting the Programme’s individual sessions.

Table 4. Canadian program learning outcomes

Day two

We began with a detailed overview of the Programme (presented by RM) and moved onto the individual program sessions. Participants worked in small groups to consider the content of each session (two per day, for five days) that makes up the Programme. We displayed the Canadian priorities identified the day before to guide participants in co-producing what needs to stay in the session, how the session can be taught, and who is best skilled at delivering the content. Each table had significant feedback that was recorded by facilitators (student research assistants). Written documents capturing this feedback have been retained and will be used to develop specific content for the Canadian program.

After summarizing the work from the morning, the final afternoon concluded with a session to strategize future directions. This included identification of a knowledge dissemination plan for our work to date, and discussion of funding opportunities to support the continued development and pilot of the Canadian program. As part of knowledge dissemination, we took the opportunity to record comments from our expert participants to develop a video and lay the summary of the planning meetings (Bayly, Peacock, Jack-Waugh, & MacRae, Reference Bayly, Peacock, Jack-Waugh and MacRae2020).

Summary and Next Steps

Our overall aim is to co-produce a dementia education program that embodies Canadian health care values, principles, and priorities for dementia care in acute care settings, and has utility and acceptability for those providing and receiving care. The work described within this Policy and Practice Note reflects the first stage of the co-production of an intervention (evidence review and stakeholder consultation; Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Madden, Fletcher, Midgley, Grant, Cox and White2017), including an environmental scan of existing Canadian dementia education programs available to acute HCPs, key informant interviews, and a planning meeting event bringing together experts from Scotland with Canadian stakeholders. During the planning meeting, participants identified Canadian priorities for dementia education, overall learning objectives for a Canadian program, and provided feedback related to each session of the Programme. Including only three key informants with lived experience of dementia in our interviews could be viewed as a limitation, but their rich accounts of their acute care experiences were useful to inform the work in the planning meeting. Additionally, we could have interviewed acute care providers prior to the planning meeting to gain their perspectives on challenges and gaps regarding dementia education; their perspectives will be highlighted via focus groups as we refine the program for implementation. Access to detailed information about the various dementia education programs in Canada was limited to the knowledge of Provincial/Territorial Alzheimer Society staff and what is publicly accessible; regardless, no dementia programs in Canada exist that are comparable to the Programme. Our work from the planning meeting is significant to moving forward with a Canadian program.

The results of this planning meeting are now being used to inform the next stage of co-production, which is the co-development of the content of the Canadian dementia education program for acute HCPs (Hawkins et al., Reference Hawkins, Madden, Fletcher, Midgley, Grant, Cox and White2017). Once the core development group (SP, MB, RM, AJW, KH, LH, JB, and NR) creates an initial program and implementation plan, these will be shared with key stakeholder groups for additional input. Of importance is to explore offering online/virtual options for program delivery, given the vastness of Canada as well as the issues the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic revealed. We will hold two focus groups with persons living with dementia and their carers, as well as a focus group with frontline acute HCPs to ensure the utility and acceptability of the Canadian program. Future research endeavours (that reflect the third stage of co-production) include acquiring funding to pilot and evaluate the Canadian program. We will further develop and maintain our website (see https://www.dementiachampionscanada.com/) to make our work visible and accessible to people who would benefit from a dementia education program for acute HCPs.

Funding

None.