The development of strategies to promote the more conscientious use of clinical tests and interventions is a growing international trend in health care, represented by a relatively new body of literature on “de-adoption” or “disinvestment” of particular procedures (Niven et al., Reference Niven, Mrklas, Holodinsky, Straus, Hemmelgarn, Jeffs and Stelfox2015). The deprescribing of potentially inappropriate medications is a foundational element of the broader de-adoption movement. There is now a substantial body of literature addressing barriers, facilitators, and strategies to support deprescribing in practice (Anderson, Stowasser, Freeman, & Scott, Reference Anderson, Stowasser, Freeman and Scott2014; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Naganathan, Carter, McLachlan, Nickel, Irwig and Turner2016; Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, To, Hendrix, Shakib, Roberts and Wiese2013; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Hilmer, Reeve, Potter, Le Couteur, Rigby and Page2015), lending further support for the growing urgency to promote the more appropriate use of medications especially among older people (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Tsang, Raman-Wilms, Irving, Conklin and Pottie2015). Considering these insights, the need to mobilize knowledge in support of prescribing practice change is paramount.

Safe and appropriate prescribing is a complex process, involving issues of over-prescription, under-prescription, and inappropriate prescription (Spinewine et al., Reference Spinewine, Schmader, Barber, Hughes, Lapane, Swine and Hanlon2007). The mandate of CaDeN is to implement a coherent multi-pronged strategy for deprescribing, as part of the solution to address over-prescribing and inappropriate prescribing. To date, efforts to encourage deprescribing via medication reviews and software alerts have primarily targeted physicians and pharmacists, with varying degrees of success (Kaur, Mitchell, Vitetta, & Roberts, Reference Kaur, Mitchell, Vitetta and Roberts2009). Approaches involving interprofessional teams have been used but little is known about how team members function together to manage polypharmacy (Bergkvist, Midlöv, Höglund, Larsson, & Eriksson, Reference Bergkvist, Midlöv, Höglund, Larsson and Eriksson2009; Mudge et al., Reference Mudge, Radnedge, Kasper, Mullins, Adsett, Rofail and Barras2016). Strategies directly targeting patients, such as consumer-directed educational interventions, yield promising results but remain in their infancy (Tannenbaum, Martin, Tamblyn, Benedetti, & Ahmed, Reference Tannenbaum, Martin, Tamblyn, Benedetti and Ahmed2014). Higher level policy approaches have thus far primarily taken the form of pay-for-performance incentives and restricted use authorization from insurers, occasionally resulting in unintended consequences that create further health-related challenges (Chen & Kreling, Reference Chen and Kreling2014; Colla, Reference Colla2014; Schaffer, Buckley, Cairns, & Pearson, Reference Schaffer, Buckley, Cairns and Pearson2016). No single initiative has simultaneously deployed a multi-level approach to deprescribing across Canada, involving patient, clinician, and policy-maker partners to advance support for deprescribing across key stakeholder groups.

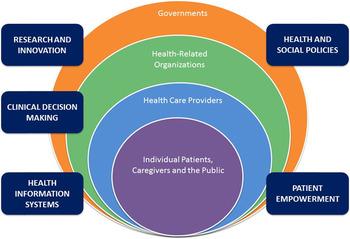

The purpose of this article is to describe the justification, theoretical foundation, and process for establishing a national network of individuals and organizations interested in the deprescribing of potentially inappropriate medications in Canada: a Canadian Deprescribing Network (CaDeN). This network represents a novel approach to mobilizing knowledge and facilitating practice change on deprescribing by organizing volunteer members into action committees based on a consolidated theory of health services transformation and health care provider practice change (Best et al., Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz2012; Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009; Michie, van Stralen, & West, Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). The multi-level, ecological approach adopted by the CaDeN is illustrated in Figure 1. Inspired by a public health perspective (Richard, Barthélémy, Tremblay, Pin, & Gauvin, Reference Richard, Barthélémy, Tremblay, Pin and Gauvin2013), the approach draws upon existing theories of health system transformation. The mandate of the CaDeN is of relevance to an international audience interested in prescribing best practices, health care transformation, and knowledge mobilization, as it proposes a unique model to achieve changes in health care that might be applied both in new national settings and for different transformational challenges in health care.

Figure 1: Ecological model of health system change.

Note: Adapted from Richard et al. (2013). Interventions de prévention et promotion de la santé pour les aînés: modèle écologique. Guide d’aide à l’action francoquébécois. Saint-Denis: Inpes, coll. Santé en action.

Problem: Use of Medication that may Cause More Harm than Benefit

Use of medication that may cause more harm than benefit is considered potentially inappropriate when safer pharmacological or non-pharmacological alternatives exist. In Canada, 42 per cent of women over the age of 65 and 31 per cent of older men are taking potentially inappropriate medications, based on estimates from prescription claims from publicly financed provincial drug plans, as defined by the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Medication List (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Hunt, Rioux, Proulx, Weymann and Tannenbaum2016). The cost of these inappropriate prescriptions approximates $419 million, and likely reaches $1.4 billion if the indirect costs of drug-induced falls, fractures, and hospitalizations are accounted for (Boulin, Diaby, & Tannenbaum, Reference Boulin, Diaby and Tannenbaum2016; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Hunt, Rioux, Proulx, Weymann and Tannenbaum2016; Tannenbaum et al., Reference Tannenbaum, Diaby, Singh, Perreault, Luc and Vasiliadis2015). Currently, 65.9 per cent of Canadians over the age of 65 report taking five or more drug classes, and 27.2 per cent report taking 10 or more over the past year, a prevalence that increases to 39 per cent in persons over 85 (Proulx & Hunt, Reference Proulx and Hunt2014). These rising rates of polypharmacy and medication inappropriateness raise important questions about quality of care and safety (Budnitz, Lovegrove, Shehab, & Richards, Reference Budnitz, Lovegrove, Shehab and Richards2011; Opondo et al., Reference Opondo, Eslami, Visscher, De Rooij, Verheij, Korevaar and Abu-Hanna2012). In addition to causing falls, fractures, and confusion, prescribing cascades are common (Rochon & Gurwitz, Reference Rochon and Gurwitz1997), which contribute to injury-related hospitalizations and death (Berdot et al., Reference Berdot, Bertrand, Dartigues, Fourrier, Tavernier, Ritchie and Alpérovitch2009). The Canadian Medical Association (2015) estimates that in the five-year period between 2006 and 2011 there were almost 140,000 hospitalizations for adverse drug reactions among seniors in Canada. Forty per cent of emergency room visits due to adverse drug events are deemed preventable (Budnitz et al., Reference Budnitz, Lovegrove, Shehab and Richards2011; Hohl et al., Reference Hohl, Nosyk, Kuramoto, Zed, Brubacher, Abu-Laban and Sobolev2011; Marcum et al., Reference Marcum, Amuan, Hanlon, Aspinall, Handler, Ruby and Pugh2012; Stockl, Le, Zhang, & Harada, Reference Stockl, Le, Zhang and Harada2010; Wu, Bell, & Wodchis, Reference Wu, Bell and Wodchis2012; Zed et al., Reference Zed, Abu-Laban, Balen, Loewen, Hohl, Brubacher and Lacaria2008).

Older adults are a particularly vulnerable population as the risk of adverse drug events increases with changes in pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and physiologic reserve as people age (Sera & McPherson, Reference Sera and McPherson2012). Those older adults living with frailty are also at higher risk of adverse effects, and several recent guidelines for chronic disease now recommend relaxed targets in this population or make reference to recommended therapy that has been specifically studied in frailty (Cheng & Lau, Reference Cheng and Lau2013; Howlett et al., Reference Howlett, Chan, Ezekowitz, Harkness, Heckman, Kouz and Abrams2016; Muscedere et al., Reference Muscedere, Andrew, Bagshaw, Estabrooks, Hogan, Holroyd-Leduc and McNally2016). Benzodiazepine drugs are among the most worrisome; they are the most frequent class of inappropriate drugs used in Canadian seniors (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Hunt, Rioux, Proulx, Weymann and Tannenbaum2016) and are associated with falls, fractures, confusion, dementia, and mortality (de Gage et al., Reference de Gage, Bégaud, Bazin, Verdoux, Dartigues, Pérès and Pariente2012; Glass, Lanctôt, Herrmann, Sproule, & Busto, Reference Glass, Lanctôt, Herrmann, Sproule and Busto2005). In Canada, 12 per cent of senior women and seven per cent of men consume sedative-hypnotics, with significant variation across provinces (Figure 2). Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is rising, with a higher mean rate of female than male consumers in Canada, approximating 20 per cent (Figure 3). Though sometimes prescribed appropriately, long-term use of a PPI increases the likelihood of Clostridium difficile infections, community-acquired pneumonia, hypomagnesemia, fractures, and both acute and chronic kidney disease (Gomm et al., Reference Gomm, von Holt, Thomé, Broich, Maier, Fink and Haenisch2016; Schoenfeld & Grady, Reference Schoenfeld and Grady2016). The prescription of long-acting sulfonylurea drugs for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes is also of concern, occupying significant market share in more men aged 65 and older than women (Figure 4). Sulfonylurea use is linked to an increased risk of hypoglycaemia, as well as falls, fractures, hospitalisation, and mortality (Cryer, Reference Cryer2008; Jafari & Britton, Reference Jafari and Britton2015). As safer pharmacological or non-pharmacological alternative therapies are available for all three classes of these drugs, these medication classes fall under the category of being potentially inappropriate in older people (O’Mahony et al., Reference O’Mahony, O’Sullivan, Byrne, O’Connor, Ryan and Gallagher2014).

Figure 2: Proportion of community-dwelling men and women over the age of 65 with potentially inappropriate use of sedative hypnotics, selected provinces, 2011 to 2014.

Notes:

9 provinces submitting claims data to the NPDUIS Database as of December 2015: Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4 represent 4 consecutive 3-monthly periods (quarters) in each calendar year.

Source: National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Figure 3: Proportion of community-dwelling men and women over the age of 65 with potentially inappropriate use of proton pump inhibitors, by province and quarter, selected provinces, 2011 to 2014.

Notes:

9 provinces submitting claims data to the NPDUIS Database as of December 2015: Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4 represent 4 consecutive 3-monthly periods (quarters) in each calendar year.

Source: National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

Figure 4: Proportion of community-dwelling men and women over the age of 65 with potentially inappropriate use of sulphonylurea drugs, by province and quarter, selected provinces, 2011 to 2014.

Notes:

9 provinces submitting claims data to the NPDUIS Database as of December 2015: Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia.

Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4 represent 4 consecutive 3-monthly periods (quarters) in each calendar year.

Source: National Prescription Drug Utilization Information System Database, Canadian Institute for Health Information.

A Brief Overview of Deprescribing

Deprescribing is the planned and supervised process of dose reduction or stopping of medications that may be causing harm or are no longer providing benefit (Thompson & Farrell, Reference Thompson and Farrell2013). The term is relatively new; it was first described in 2003 in an article which outlined steps for deprescribing (Woodward, Reference Woodward2003). However, the practice of reducing inappropriate medication use is not new. Studies examining the impact of reducing or ceasing medication date back several decades (Iyer, Naganathan, McLachlan, & Le Conteur, Reference Iyer, Naganathan, McLachlan and Le Conteur2008).

In Canada, an expert panel of geriatricians, family physicians, pharmacists, and nurse practitioners recently identified 14 drug classes for which deprescribing guidelines would be useful (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Tsang, Raman-Wilms, Irving, Conklin and Pottie2015). Several generic frameworks outline steps for clinicians to follow when deprescribing that include, among others: taking a full medication history, assessing the ongoing indication and effectiveness of each medication, assessing for side effects of each medication, determining whether any symptoms could be caused by a medication, determining whether another medication or non-pharmacological approach would be as or more effective and safer, and ultimately, whether the medication dose can be reduced, stopped, or switched (Reeve & Wiese, Reference Reeve and Wiese2014). However, prescribers and patients continue to express barriers to deprescribing that include difficulty weighing benefits and risks, or continuing or stopping specific medications, as well as pressure to continue to prescribe according to prescribing guidelines (Reeve et al., Reference Reeve, To, Hendrix, Shakib, Roberts and Wiese2013; Turner, Edwards, Stanners, Shakib, & Bell, Reference Turner, Edwards, Stanners, Shakib and Bell2016). A recent Canadian effort to produce class-specific deprescribing guidelines attempts to address these barriers (Conklin et al., Reference Conklin, Farrell, Ward, McCarthy, Irving and Raman-Wilms2015).

Interprofessional teams are emerging as a common approach to caring for older people (Trivedi et al., Reference Trivedi, Goodman, Gage, Baron, Scheibl, Iliffe and Drennan2013). Studies have demonstrated reduction in medication exposure through pharmacist/physician/nurse-conducted medication reviews, and through specialist and multidisciplinary collaboration (Gnjidic, Le Couteur, Kouladjian, & Hilmer, Reference Gnjidic, Le Couteur, Kouladjian and Hilmer2012; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Vogt-Ferrier, Hasso, Le Saint, Dramé, Zekry and Prudent2012; Mudge et al., Reference Mudge, Radnedge, Kasper, Mullins, Adsett, Rofail and Barras2016). Considering these points, an interprofessional approach to deprescribing and ensuring that appropriate alternative pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments are in place is essential. Regardless of whether a framework or guideline approach is undertaken, deprescribing strategies should consider patient complexity and multimorbidity, and may be guided by recent innovations such as individualised medication, genetics, and pharmacogenetics testing. Approaches to deprescribing require attention not only to benefit and harm, but also to factors associated with frailty, life expectancy, and patient goals (Holmes et al., Reference Holmes, Min, Yee, Varadhan, Basran, Dale and Boyd2013; Todd & Holmes, Reference Todd and Holmes2015).

A Theoretical Foundation for System-Wide Deprescribing

Reducing the use of potentially inappropriate medications, such as benzodiazepines, long-acting sulfonylurea drugs, and PPIs, is a complex health system problem. Efforts to promote deprescribing therefore require attention to multiple levels of action across multiple stakeholder groups (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Stowasser, Freeman and Scott2014). The most immediate stakeholders requiring attention are patients, informal caregivers, and health care providers, as these are the key actors involved in the prescribing and consumption of medications. However, the organizational and policy contexts in which prescribing and deprescribing take place cannot be ignored. As such, a comprehensive approach to promoting deprescribing requires a theoretical foundation that encourages consideration of this wide variety of influences.

We examined theories of implementation and health system change to help guide the strategic development of CaDeN. We integrated systematic reviews and literature syntheses on implementation science (Damschroder et al., Reference Damschroder, Aron, Keith, Kirsh, Alexander and Lowery2009; Nilsen, Ståhl, Roback, & Cairney, Reference Nilsen, Ståhl, Roback and Cairney2013), innovation adoption (Chaudoir, Dugan, & Barr, Reference Chaudoir, Dugan and Barr2013), and health care transformation (Best et al., Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz2012), and identified themes across these distinct bodies of research in order to inform the strategy for the initiative. The network strategy was founded on three key themes: (1) a multi-level approach to system transformation, (2) an understanding of drivers of human behaviour change, and (3) principles of network development.

A Multi-level Approach to System Transformation

The central feature of the theoretical foundation for CaDen is a multi-level approach including strategic attention to four interdependent levels of the health system: individual patients (and the public), health care providers, health-related organizations, and governments (Figure 1). Actions across these four levels are interdependent in the sense that the behaviour of actors at each level is shaped by various social and legal institutions (rules, regulations, norms, and expectations) that can span multiple layers (e.g., charter rights, privacy law, or the norm of Canada’s universal health care system) or be situated within a single layer (e.g., charters of professional colleges) (Kotter, Reference Kotter1996). The initiatives that CaDeN prioritizes span these multiple levels, targeting the following strategic areas of focus: (a) empowerment of patients, caregivers, and the general public; (b) clinical decision-making across health care provider and professional groups; (c) health and social policies related to prescribing appropriateness; (d) health information systems; and (e) research and innovation related to deprescribing. Each of these actions/initiatives may originate with more than one type of organization, government, or profession and constitute an important cross-cutting element of the national strategy to bring about health system change to promote deprescribing.

One key framework that helped to guide the development of the network was the seminal work of Best et al. (Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz2012) on large system transformation in health care. In their realist review of strategies to promote change across entire health systems, Best et al. (Reference Best, Greenhalgh, Lewis, Saul, Carroll and Bitz2012) reported five simple rules to guide transformational efforts. The first of these rules was to engage individuals at all levels in leading change efforts, establishing distributed leadership across levels of the health system. Accordingly, CaDeN adopted a multi-level approach emphasizing the importance of distributed leadership among each of the stated health system stakeholder groups. One key adaptation of this model is that where Best et al. described a cyclical approach to transformational change, the leaders of CaDeN believe that efforts across patient, clinician, and decision-making stakeholder groups need to be simultaneous and synergistic.

Understanding the Drivers of Human Behaviour Change

A second key element of the theoretical foundation for CaDeN is to situate the activities of the network within an understanding of the factors driving human behaviour change (Michie et al., Reference Michie, van Stralen and West2011). Michie et al. suggested that human behaviour is a function of the interaction between three key determinants: capability, opportunity, and motivation. When an individual has (a) the capability to engage in a particular action (e.g., the knowledge and skills of what and how to deprescribe), (b) the opportunity to engage in that action (e.g., dedicated time in a professional environment for conversations between patients and prescribers on deprescribing), and (c) the motivation to engage in that action (e.g., concern about the harms associated with inappropriate medications), then the action itself will occur. Essentially, this model of behaviour change recognizes that simply providing information is not enough to bring about changes in clinical practice or public action. Instead, motivation and opportunities to engage in a new behaviour such as deprescribing are also essential.

In the case of CaDeN, the goal is to achieve changes at each health system level that bring about the conditions to enable deprescribing. This means that the kinds of activities focused, for example, on health care providers will be substantively different than those focused on policy – these different strategic actions are intended to achieve different outcomes. For actions focused on health care providers, the goal is to enhance capability for deprescribing. For actions focused on policy, the goal is to promote policy changes that enable opportunities for deprescribing to take place. For actions focused on patients, the goal is to drive motivation on the part of patients to engage in conversations about deprescribing and bring about culture change. In this way, a coordinated strategic vision for CaDeN that integrates different actions at different health system levels is central to achieving the overall goal of the network.

Principles of Network Development

Networks seeking to make changes in health and social care can take many forms, consisting primarily of organizations, individuals, or both (Bess, Speer, & Perkins, Reference Bess, Speer and Perkins2012; Provan & Kenis, Reference Provan and Kenis2008). Fundamentally, networks depend on the commitment of individual members who have either personal or organizational incentives to participate (Ysa, Sierra, & Esteve, Reference Ysa, Sierra and Esteve2014). Developing the network membership and articulating the network goals are thus important elements of ensuring the network’s success.

Agranoff and McGuire (Reference Agranoff and McGuire2001) suggested that there are four key activities involved in network development when initiating successful networks: activation, framing, mobilizing, and synthesizing. Activation refers to integrating the right network members early in the network development process, and developing a strategy to leverage these members’ resources. Framing refers to shaping the overall culture of the network, influencing how network members view their participation and the network in general. Mobilizing refers to the establishment of systematic processes to share and use network resources throughout the life of the network. Synthesizing refers to establishing network conditions that make interaction between network members as easy as possible, harnessing the creative potential of spontaneous interaction within the network.

Canadian Deprescribing Network

CaDeN was initiated through a Partnership for Health System Improvement research grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. Based on existing professional networks, this research grant brought together health system stakeholders with expertise on patient empowerment, clinical deprescribing strategies, and policy levers to take action on promoting deprescribing among older people living in the community in Canada. In order to determine interest in establishing a formal national network, and expand the group of stakeholders beyond the small group involved in developing the research grant (i.e., the network development activity of activation), the leadership hosted an inaugural symposium on safe and appropriate medical therapy in Canada. Invitations were sent to a select group of policymakers, patient representatives, health care providers, and researchers, who met in person in January 2015 to discuss issues associated with promoting safe and appropriate use of medications and to determine next steps for a formally established network (Canadian Institutes of Health Research [CIHR], 2015).

This first symposium represented the network leadership’s efforts in framing the issue the network would develop, and initiating the mobilization of resources for future network actions. A key focus of the inaugural meeting was the commitment to apply a sex- and gender-based analysis framework to the initiative, recognizing that older women and men exhibit different patterns of potentially inappropriate drug use. For instance, women are more likely to take certain classes of potentially inappropriate medication, and have higher chances of experiencing adverse drug events (Bierman et al., Reference Bierman, Pugh, Dhalla, Amuan, Fincke, Rosen and Berlowitz2007). Older men with dementia experience drug-related hospitalizations more frequently than women due to incident use of antipsychotic medication (Rochon et al., Reference Rochon, Gruneir, Gill, Wu, Fischer, Bronskill and Bell2013). Figures 2–4 illustrate clear sex differences in patterns of use of benzodiazepines, sulfonylurea drugs, and PPIs among Canadian seniors.

Following the inaugural symposium, the network leadership developed a strategic vision based on two inter-related aspirational goals. The first was to reduce harm by curbing the use of potentially inappropriate medications among older people by 50 per cent by the year 2020. The second was to promote health by advocating for access to safer pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. Dividing participants who were willing and interested into strategic committees based on their interests and expertise, the network leaders asked volunteers to consider how they might work towards achieving these goals within five different strategic groups.

The strategic committees that were initially outlined were based on the importance of a multi-level approach and sought to foster distributed leadership to enable health system transformation. After several iterations and some changes in committee membership, the final breakdown of the strategic foci of each CaDeN committee is as follows:

-

1. Public awareness, engagement, and action on deprescribing

-

2. Health care providers’ motivation, awareness, and capacity to deprescribe

-

3. Policy change at the federal, provincial, and territory levels

-

4. Integration of deprescribing strategies within health information systems

-

5. Research capacity and impact, within a sex-and-gender-based analysis framework

The activities of each committee were determined based on the expertise and commitment of each committee’s members, maintaining a realistic focus on what changes could be made in a five-year time frame. For instance, the public outreach strategy will tailor messages and activities differently to three different target audiences: healthy/fit seniors, the frail elderly, and the caregivers and children of the frail elderly. Further details about the specific goals and activities outlined as priorities by each sub-committee may be found on CaDeN’s official website http://deprescribing.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/ACTION-PLAN-ENGLISH-for-Deprescribe_org-updated-March-15th-2016.pdf. The network’s leadership, or core executive committee, maintains oversight and considers how the activities of each strategic committee will contribute to enabling health care providers, patients, and families to work together on deprescribing.

Evaluation

Evaluation of network performance and the degree of network progress on achieving its goals is a complex and challenging task. Achieving a 50 per cent reduction in the use of unnecessary or potentially harmful medication among seniors is the primary goal of the initiative. However, it is also important to examine the wide range of process goals and secondary outcomes achieved throughout the course of network action. The evaluation plan for CaDeN thus takes a multi-pronged approach, focusing on (a) the primary outcome of reducing the use of potentially harmful or unnecessary medication among seniors, (b) process goals related to the actions taken by each strategic committee, and (c) secondary outcomes representing network performance in alternative ways.

To simplify the quantitative evaluation of the network, and to be able to monitor and gauge success, the three specific medication classes detailed earlier were selected as an indicator of potentially harmful and inappropriate medication use among seniors: the benzodiazepines, the long-acting sulfonylurea anti-diabetic agents, and the PPIs. These three medication classes are frequently used in Canada, are prescribed for widely different indications, and are all supported by rigorous evidence of harm associated with chronic use. Changes in use over time will be monitored in seniors under public drug claim coverage in nine different provinces at regular intervals, in collaboration with the Canadian Institute for Health Information. These data will be collected at quarterly intervals throughout the duration of the project to enable an interrupted time series analysis of changes to drug claims data before, during, and after CaDen engages in its core activities. In addition, we intend to repeat previous analyses to examine changes in the proportion of seniors on public drug programs that had at least one claim for a drug from the Beers Criteria Medication list, and a change in the proportion of seniors that had a claim for two or more drugs, using the same methodology as previous reports (Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Hunt, Rioux, Proulx, Weymann and Tannenbaum2016; Proulx & Hunt, Reference Proulx and Hunt2014).

Despite some inherent challenges in collecting accurate drug use data, these are the best available data indicating the use of these medication classes across the Canadian population. There may be differences in population characteristics (such as age and health status) between seniors with and without public coverage. In provinces with lower proportions of seniors who have claims accepted by the public plan (i.e., Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick), drug utilization patterns among those with public coverage are less likely to be reflective of utilization patterns among all seniors in the province. Although this impacts comparisons between provinces, it is not expected to impact trends within provinces over time.

Despite acknowledged challenges with the collection and reporting of data regarding the dispensing and use of potentially inappropriate medications, these data suggest that wide variation persists across the jurisdictions represented, beyond what might be expected due to differences in program design and population health and demographics. Such wide variation suggests differences in prescribing behaviour, calling for efforts to implement best practices regarding safe and appropriate medications on a Pan-Canadian scale. These data inform the goals and strategy of CaDeN, and provide an essential baseline picture of the issue in Canada.

In addition to examining changes in the primary outcome of drug claims data, the network evaluation strategy focuses on mixed-methods data representing process goals and secondary network outcomes. Process goals are determined by each strategic committee, based on the specific activities they will undertake to achieve the primary goals. For example, in order to measure the success of efforts to raise public awareness, a national phone survey is currently being conducted among community-dwelling seniors at the onset of implementing the action plan, and again in 2020. The committee focused on health care provider motivation, awareness, and capacity to deprescribe will track progress in completing actions such as (a) developing a toolkit of evidence-based deprescribing resources for dissemination to health care providers across the country, (b) publishing commentaries or letters to the editor in professional academic journals to help increase awareness of deprescribing, and (c) collaborating to support continued professional education courses focused on deprescribing. Beyond simply identifying whether these actions have been performed, the evaluation strategy will engage key network members in qualitative interviews to identify how and why particular activities have been accomplished, and to explore network members’ beliefs about what is most effective at creating targeted changes and why. Actions and engagement of various government organizations, such as the Pharmaceutical Directors’ Forum, will be tracked to evaluate the progress of the policy committee, as well as the development of new or modification of existing policies that support the reduction of potentially inappropriate prescriptions or access to safer, non-pharmacological alternatives.

The final domain of the evaluation is focused on secondary network outcomes. These secondary outcomes emphasize the intrinsic value of the network as a mechanism to diffuse knowledge and foster collaboration on deprescribing across the country. Examples of secondary outcomes include changes in network density and the development of new personally meaningful professional relationships, representing the quality of the network in facilitating collaboration and change (Kenis & Provan, Reference Kenis and Provan2009). Secondary outcomes are developed based on network theory and research, and capture the perhaps less obvious but nonetheless important effects of a Pan-Canadian network such as CaDeN.

Conclusion and Next Steps

CaDeN is a theoretically informed, multi-level group of organizations and individuals dedicated to advancing the deprescribing of potentially inappropriate medications in Canada. In this article we outlined the justification, theoretical foundation, development, and evaluation plan for the network. By introducing the network in this way, we hope to garner interest from potential collaborators across the country and contribute to the body of knowledge on strategies for policy and practice change to promote the health and well-being of an aging population. Although the network has come a long way in its development thus far, it has much distance to travel to achieve its ambitious year 2020 goals.

The network hosted its second annual symposium on safe and appropriate medical therapies in January 2016, expanding its membership and developing further support for its mandate (CIHR, 2016). Already, a number of partners and organizations have joined the campaign, representing stakeholders from seniors groups, patient safety groups, government, pharmaceutical policy committees, and professional organizations. Each individual and group participating in the network offers skills, knowledge, and access to additional network members, proportional to their resources in contributing to advancing deprescribing in Canada. The network will continue to develop and advance deprescribing across Canada, remaining open to collaboration with a wide range of stakeholders to bring about real transformation in Canadian health care.