1. Nominals at the interfaces

Since the appearance of Abney's (Reference Abney1987) seminal dissertation, the study of nominals has expanded dramatically (Ritter Reference Ritter and Rothstein1991, Reference Ritter1992, Reference Ritter1993; Valois Reference Valois1991; Li Reference Li1999; Ghomeshi Reference Ghomeshi2003; Bošković Reference Bošković2005; Cheng and Sybesma Reference Cheng and Sybesma2012; Piriyawiboon Reference Piriyawiboon2011). The extended nominal projection has been compared with the extended verbal projection, with suggestions of strict parallelism between the two (Ogawa Reference Ogawa2001, Megerdoomian Reference Megerdoomian, Freidin, Otero and Zubizarreta2008), along with a proliferation of functional projections (nP, NumP, ClP, PossP, DP, KP, among others). The study of nominal structure impinges on our understanding of noun incorporation (Baker Reference Baker1988, van Geenhoven Reference van Geenhoven1998, Massam Reference Massam2001), semantics (Chierchia Reference Chierchia1998), phases (Newell Reference Newell2008), and prosody (Clemens Reference Clemens2014). The study of how nominals fit into the clausal spine impacts our understanding of case (Massam Reference Massam, Johns, Massam and Ndayiragije2005, Diercks Reference Diercks2012) and argument structure (Rosen Reference Rosen1989, Mithun and Corbett Reference Mithun, Corbett and Mereu1999, Chung and Ladusaw Reference Chung and Ladusaw2004). The questions this special issue addresses include but are not limited to the following:

• What functional projections are found in the extended nominal projection? Is the functional hierarchy universal (Cinque Reference Cinque2010), language-specific, or is its variation constrained in some way (Wiltschko Reference Wiltschko2014)?

• What kinds of reduced nominal expressions are found in natural language? Bare NPs? Bare NumPs? Cl+N expressions without numerals? Caseless nouns? How does this inventory of reduced nominals inform us about, and relate to noun incorporation and pseudo noun incorporation?

• What is the phase structure of nominals? What is the evidence for DP phases (Svenonius Reference Svenonius, Adger, Cat and Tsoulas2004)? Is there an internal nP phase corresponding to vP (Marantz Reference Marantz2001, Newell Reference Newell2008)?

• What are the prosodic properties of nominals and reduced nominals (Dyck Reference Dyck2009, Clemens Reference Clemens2014, Richards Reference Richards2017)?

• What are the semantic properties of nominals and reduced nominals? Is there a strict correlation between the size of the nominal and its semantic properties (Dayal Reference Dayal2011, Reference Dayal2015)? Do incorporated nouns and pseudo incorporated nouns have a uniform semantics (van Geenhoven Reference van Geenhoven1998) or not (Dayal Reference Dayal2015)?

2. Article summaries

The four papers contained in this volume address these and other questions related to nominals and the behaviour of nominals at the interfaces. These papers are a sample of presentations from the Nominals at the Interfaces workshop at Sogang University in November of 2018.

2.1 Deriving four generalizations about nominals in three classifier languages

Phan, Trinh, and Phan's paper examines the syntactic and semantic properties of number and nouns in three East Asian classifier languages: Mandarin, Vietnamese, and Bahnar (bdq), the latter being an Austroasiatic language.

They discuss a number of micro-parametric studies of number-marking languages and further note that micro-parametric variation among classifier languages is comparatively under-represented. It is with this background in mind that they present their observations. They note that:

• DEM can combine directly with CL + N (without a numeral) in Mandarin and Vietnamese, but not in Bahnar.

• A bare CL + N can be an argument in Vietnamese, but not in Mandarin and Bahnar.

• A bare NUM + CL + N can be definite in Bahnar and Vietnamese, but not in Mandarin.

• A bare NP can be definite in Bahnar and Mandarin, but not in Vietnamese.

Their analysis is very much along the lines of Chierchia (Reference Chierchia1998), taking the following lexical entries as a departure, where ‘dog’ represents the phonological form for dog in Bahnar, Vietnamese, or Mandarin:

(1)

a. 〚dog〛w = λx. x is a singular dog = {a, b, c}

b. 〚dog’〛w = λx. x is a singular dog or a plurality of dogs = {a, b, c, a

${\oplus} $b, a

${\oplus} $b, a ${\oplus} $c, b

${\oplus} $c, b ${\oplus} $c, a

${\oplus} $c, a ${\oplus} $b

${\oplus} $b ${\oplus} $c}

${\oplus} $c}

Phan et al. then lead us through an array of sophisticated semantic definitions for numerals and classifiers. They capture the differences among the three languages above by positing that numerals and classifiers can combine differently in different languages. In some languages, the classifier combines with the noun, and then this complex combines with the numeral. In other languages the numeral and the classifier combine first, and then this complex combines with the noun.Footnote 1 The other ingredients in their analysis are a null THE (similar to English the, and reminiscent of Paul's Reference Paul2016 analysis of Malagasy) and a null KIND. The authors then account for the four observations above on these three languages with the machinery in (1).

2.2 Oblique differential object marking, nominal structure and licensing strategies

Irimia examines differential object marking (DOM) in Spanish, Romanian, Gujarati and Mandarin Chinese. Her study investigates the difference between DOM and pseudo-incorporation and the different licensing conditions for nominals of different sizes. The key finding of her work is that DOM requires a licensing condition in addition to Case. Specifically, DOM interacts with a sentience feature on K.

She first investigates Spanish, a language with a wealth of studies on DOM and challenges the notion that DOM-less nominals are necessarily pseudo-incorporated (Ormazabal and Romero Reference Ormazabal and Romero2013). Instead, she shows that López (Reference López2012)'s Case-licensing proposal is more promising. The two approaches are summarized below.

(2)

a. A nominal that lacks DOM necessarily undergoes PNI.

b. A nominal that lacks DOM is still Case-licensed, but in a different way from DOM nominals.

She presents data from Romanian that show a clear contrast between PNI nominals and DOM-less nominals. Unlike the PNI nominals, the DOM-less nominals act as though they require Case-licensing. Her key analysis, then, rests on the following proposals.

(3)

a. DOM-less nominals are DPs. D requires Case.

b. DOM nominals are KPs. K is licensed by a sentience requirement (discussed below).

c. PNI nominals are either bare NPs or bare NumPs.

Since D is the locus of Case assignment, both DOM-less and DOM nominals require Case. DOM nominals are further licensed by a sentience requirement on K. K, as a funtional projection high in the extended nominal projection, is responsible for sentience, perspective, interaction between speech act participants and the like, along the lines of Speas and Tenny (Reference Speas, Tenny, Di Sciullo and Aktuell2003) and Ritter and Wiltschko (Reference Ritter and Wiltschko2019). The sentience feature on K is checked by a functional projection in the vP layer. PNI nominals, lacking a D head, do not receive Case and are licensed in a different way. There are many proposals on the table for how they are licensed, but these are not explored in detail, as PNI is not the object of Irimia's analysis. She then goes on to apply her analysis to Gujarati and to Mandarin Chinese.

The core contribution of Irimia's article is twofold. First, she shows that PNI is distinct from differential object splits. Second, she shows that both DOM and DOM-less nominals are Case marked. DOM nominals, in addition, require “something else” (in Irimia's words) – namely DOM nominals are licensed by a sentience feature.

2.3 Displaced sentential complements to nouns in German

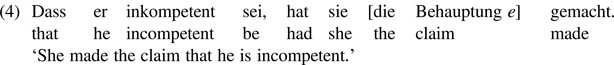

Blümel analyzes a hitherto undocumented construction in German in which clausal complements to a noun can appear in a displaced position external to the DP. Here is the example that he gives to illustrate this phenomenon.

He compares displaced noun complement clauses (NCC) to extraposed PPs, pointing out several similarities between the two constructions. He notes, however, some curious properties of extracted NCCs. In particular, they contravene the Specificity Condition, as they are extracted out of definite DPs. Blümel argues that a more nuanced view of extraction from DPs must be undertaken in light of data such as example (4).

After a discussion of previous work on extraction from nominals, notably Chomsky (Reference Chomsky, Culicover, Wasow and Akmajian1977) and Davies and Dubinsky (Reference Davies and Dubinsky2003), Blümel discusses how the German NCC extraction structure fits with (or doesn't fit with) proposals therein. As stated above, he shows that NCC extraction obeys many of the standard constraints on movement, but extraction out of a definite DP is permitted.

Blümel does note that the lack of robust judgments on the data indicate that more delicate methods must be used to investigate this phenomenon further. As such, he states that the preliminary analysis he gives should be taken as tentative. He suggests that the displaced NCC raises to SpecCP by A-bar movement. One line of support for this is that the displaced NCC can undergo long-distance movement in those varieties of German that otherwise allow long-distance A-bar movement. He ends with some suggestive remarks for future research on this topic.

The core contribution of Blümel's article is that it is the first description of the phenomenon of NCC extraction in German, along with a tentative analysis. The broader impact of his contribution is that the properties of extraction from DPs cross-linguistically are more nuanced than previously thought and thus further investigation is required.

2.4 Definiteness in Laki: Its interaction with demonstratives and number

In this article, Taghipour describes double definiteness marking in Laki (lki), an under-described Kurdish language.

Taghipour offers several diagnostics showing that the two definiteness markers in Laki have different properties, concluding that they are not the same morpheme. She compares the Laki facts with similar, well-known facts in Scandinavian, but concludes that the Scandinavian facts are different from those of Laki. Thus, the analysis used to account for Scandinavian cannot be carried over to Laki.

She proposes an elegant analysis in which the observed forms fall out from agreement (or lack thereof) with two distinct features: [uN] and [u def]. She argues that the DP-internal definiteness marker is a reflex of agreement with [u def] on N, which is triggered by the [uN] feature on D. In indefinite DP, this feature remains unvalued and is deleted, following Preminger's (Reference Preminger2014) theory of failed agreement.

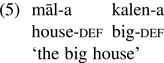

A discussion of number marking and demonstratives is then undertaken, including a cross-dialectal and cross-linguistic discussion of the intriguing properties of number marking in Indo-Iranian and its interaction with definiteness and anaphoricity. The following paradigm illustrates the pattern in Laki for the reader's reference.

Taghipour adopts Ritter's (Reference Ritter1992) NumP projection and proposes that Num and D fuse in some environments, ultimately leading to the pattern above. In the final part of her analysis, she proposes that agreement facts between D and N can also account for the facts with anaphoric and deictic determiners.

3. Concluding remarks

The four articles contained in this issue cover a tremendous amount of linguistic diversity, including data from Mandarin Chinese, Vietnamese, Bahnar (Austroasiatic), Spanish, Romanian, Gujarati, German, and Laki (Indo-Aryan) along with other Kurdish varieties. In addition, these articles touch on a number of areas in which the study of nominals informs our understanding of the interfaces in linguistics, such as the ever-popular line of inquiry regarding how nominals of different sizes inform our understanding of the syntax-semantics interface. Phan et al. and Irimia address this topic and open further avenues for research in both classifier and DOM/PNI languages. Blümel's article addresses how DP structure interfaces with clausal structure and the lexical semantics of embedding verbs. Finally, Taghipour's article addresses the syntax-semantics interface with regard to Laki number and definiteness marking. It is hoped that the articles in this issue stimulate further exciting research on these and other related topics.