The Concept of Brain Death

Internationally, death is determined either by irreversible cessation of heartbeat and breathing (cardiopulmonary death) or by irreversible cessation of functions of the brain (brain death). In the United States, for instance, each state has laws for determining these two categories of death informed by the Uniform Determination of Death Act.Footnote 1

In most Western cultures, treating a person only as a mere means to an end of another is a challenge to core concepts of human dignity as Immanuel Kant and other eighteenth-century philosophers argued.Footnote 2 Contemporary ethicists have always argued that, transferring organs to another person either from a living donor or from postmortem procured organs must be performed in a way that guarantees (1) human dignity, (2) autonomy, and (3) social justifiability.Footnote 3, Footnote 4

Phenomenological dignity as an applied concept hinges on cognition as essential for human identity and for perceiving others as human beings to be treated with the same dignity that one would expect for oneself. This concept is supported by a reflexive mode of dignity in which the autonomous (re-)evaluation and adjustment of actions is facilitated by relating intention, action, and consequences to commonly accepted values and human rights. Mutual value-based appreciation of humans goes hand in hand with a value-driven evaluation and adjustment of interaction, turning dignity into a relational concept and guiding principle of human coexistence and the basis for social justifiability. Looking at brain death, all dimensions of dignity are crucial for evaluating values, moral concepts, and needs of donors and recipients of organs alike.Footnote 5

Only against this background could the concept of brain death become at the same time the medical basis and ethical justification for moving from life-sustaining intensive care for the brain-dead person to organ explantation, weighing the interest of the living recipient against the interest of the deceased donor.

It is this amalgamation of medical and ethical dimensions of brain death that makes organ procurement a widely accepted practice in Western culture. This is especially true because of the potential for other procurement strategies, such as procurement from non-heart-beating donors (donation after circulatory death [DCD]), which require careful, detailed, and transparent protocols to prevent a potential for conflicts of interest regarding treatment and verification of the death of the potential donor.Footnote 6, Footnote 7 Circulatory death is, if not clearly defined as the irreversible cessation of cardiovascular circulation, potentially reversible. Furthermore, it can be prognostically highly dependent on a number of arbitrary, concomitant circumstances (time, temperature, and cause). Strict protocols are required, including electrocardiography and blood pressure monitoring, to assure that death has occurred and is permanent. Given that DCD donation may also lead to decreased quality of recovered organs due to prolonged ischemia, it has thus to be seen as a procedure only applicable in settings with reliable clinical standard operating procedures implemented in an evidence-based mode by well-trained medical personnel.Footnote 8, Footnote 9

Development of Brain Death Determination in China

In 2003, the Ministry of Health drafted Standards for Determining Brain Death (Draft for Comments) and Technical Specifications for Determining Brain Death (Draft for Comments). In 2009, the Ministry of Health revised the two documents. In March 2012, the National Health and Family Planning Commission (the former Ministry of Health) assigned Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University as the Brain Injury Quality Control Evaluation Center. In 2013, the Center further revised and combined the two documents into “Brain Death Determination Criteria and Technical Specification (Adult Quality Control Version).”Footnote 10 The English version was published as “Criteria and practical guidance for determination of brain death in adults (BQCC version).”Footnote 11 Experts consider the 2013 version as identical with the 2009 criteria.Footnote 12 A comparison study concludes that Chinese criteria were stricter than those of the United States, had a lower positive rate (89.2% vs. 24.3%), had significantly greater money (5.6×) and time (18.9×) costs, and were considered slightly more reliable by doctors.Footnote 13 This may surprise given the history of abuse in Chinese transplantation including sourcing organs from prisoners and forced organ harvesting.Footnote 14, Footnote 15 Ding et al. claimed that the ethics committee approval was unnecessary given publication of criteria in national journals “which represent the legal status of this evaluation” and established clinical practice for component steps (although families were informed).Footnote 16

The first documented brain death diagnosis in China was performed on February 25, 2003, in Wuhan, Hubei Province.Footnote 17 The brain death determination was carried out according to the published 2003 draft. In November 2003, the kidneys of a boy diagnosed as brain dead were used for transplantation with the consent of the parents.Footnote 18 Both events were considered breakthroughs in Chinese transplant medicine. Since then, there have been reported increasing numbers of organ donations after brain death.

However, these criteria and technical specifications represent a suggested medical standard; it is not a standard procedure, a mandatory guideline for medical practitioners, or an administrative regulation. Above all, the standard is not legally binding.Footnote 19 There is as yet no brain death legislation in China and circulatory death is the legal standard.Footnote 20 Huang Jiefu, then Vice Minister of Health, told Chinese reporters in 2006 that “It is currently illegal to use organs from brain-dead people for transplantation.”Footnote 21 The current lack of legislation on brain death presents obstacles for China to adopt this process for organ donation.Footnote 22 Similarly, China Daily acknowledged in a report in 2007 that “it is illegal to take organs from the brain-dead for transplant purposes” in China.Footnote 23 However, Chen Zhonghua, the leading transplant surgeon promoting organ donation after brain death insists that there is no law in China explicitly addressing this issue. Therefore, voluntary and unpaid organ donation after brain death is reasonable and not illegal.Footnote 24

Although the criteria for brain death and the suggested procedures of brain death determination have been published since 2003, efforts to translate these medical procedures into law or policy remained unsuccessful.Footnote 25 In 2017, Huang Jiefu expected that brain legislation would not be possible within 20 years.Footnote 26 Now, new hope is on the horizon, when in 2018 a special committee of the national legislature stated that it is necessary for the country to specify the legalities of brain death.Footnote 27

Abuse of Brain Death Determination in China

A recent study published in the Chinese Medical Journal evaluated a total of 550 brain death cases from 44 hospitals in China. It was reported that the performance of brain death determination in most of the cases conforms with the BQCC criteria. In about 73% of the cases, two separate brain death examinations were successfully carried out with at least a 12-h waiting period between. All brain death cases were reportedly determined by at least two qualified physicians.Footnote 28

In parallel to the reported promising and encouraging developments in brain death determination practice in China,Footnote 34 abuse of brain death definition has also emerged. In a variety of Chinese medical publications, transplant organs were claimed to be from “brain-dead donors,” whereas organ procurement processes indicated otherwise.Footnote 35 We have evaluated selected cases (from military hospitals, university hospitals and other civilian hospitals) carefully, and the results of our evaluation are summarized below.

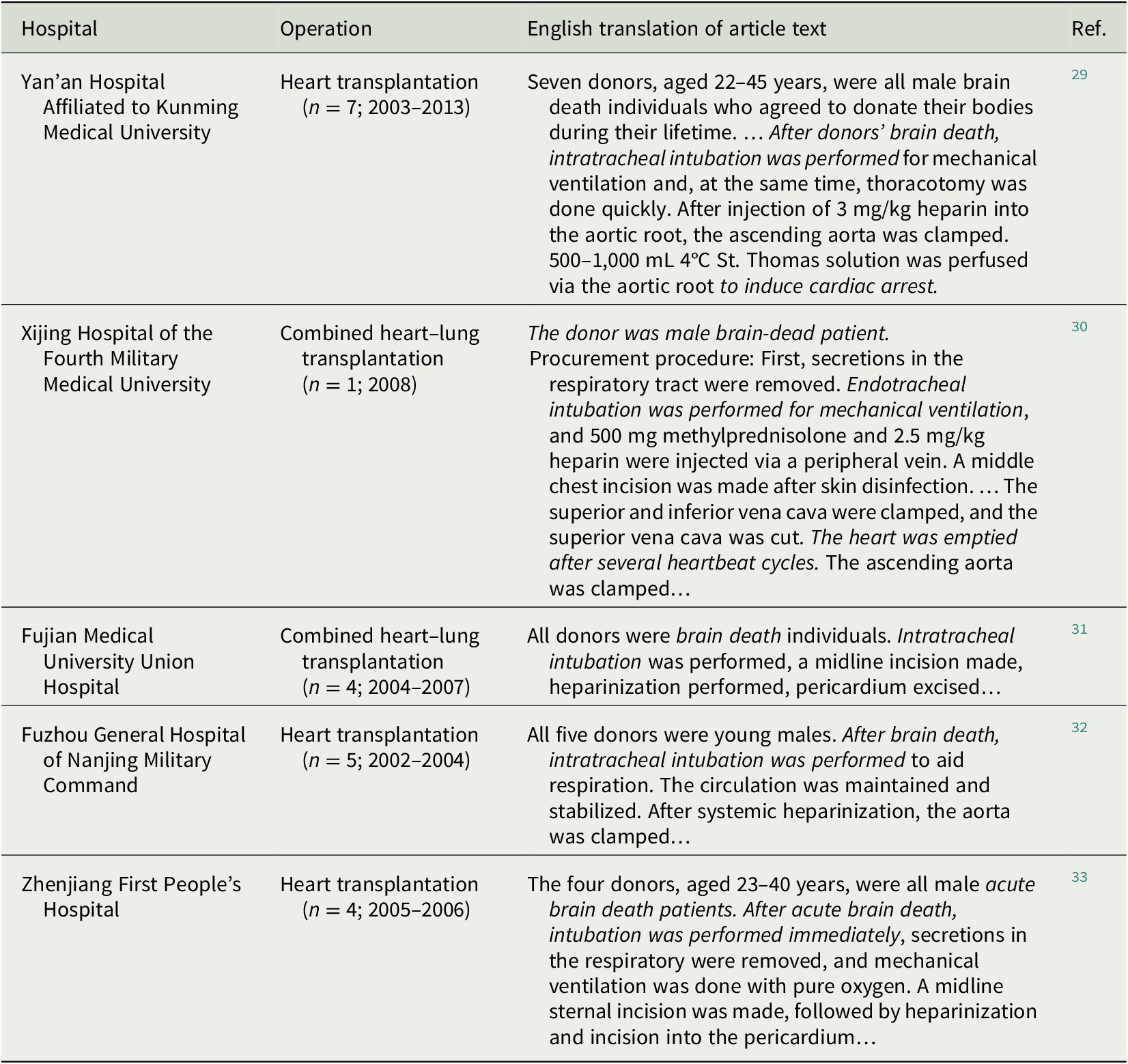

The phrases “brain death determination” or “brain death diagnosis” cannot be found in any of the articles listed in Table 1. It was simply claimed that the “donors” were brain dead, without mentioning any determination procedure or criteria. On the contrary, a brain death determination was obviously not performed because the donors were not ventilator-supported (thus no apnea test) before organ procurement. Apnea testing is a core mean of determining brain death.Footnote 36 The Chinese brain death determination guidelines emphasize that “Apnea and depending on mechanical ventilator completely to maintain ventilation are necessary for brain death determination.”Footnote 37 “Apnea should be confirmed by the apnea test according to the strict procedures” by “disconnecting the patient from ventilator for 8–10 min.”Footnote 38 Thus, a patient undergoing determination for brain death must already be on a ventilator. In the cases listed in Table 1, however, intratracheal intubation was performed after “brain death,” and the intubation was directly followed by organ procurement operations, indicating that the mechanical ventilation served only the purpose of organ harvesting.

Table 1. Transplantation Cases Involving Organs from Claimed “Brain-Dead” Donors

Moreover, in the first two cases listed in Table 1, the organ procurement procedure indicates undoubtedly that the heart of the donor was functioning. Without a brain death determination, only circulatory death criteria can apply. Thus, these heart-beating donors were not heart-beating brain-dead organ donors. This means that the condition of these donors neither met the criteria of brain death nor those of cardiac death. In other words, the “donor organs” may well have been procured in these cases from living human beings and the “donors” killed by the medical professionals through organ explantation.

It is puzzling how such superficial mistakes as the “after-brain-death-intubation” could get published. One explanation is that the authors do not care about what they are saying because there would be no consequences anyway. The more likely possibility is that the authors did not understand brain death and did not realize that they were actually documenting their own crime. Huang Jiefu, Chairman of the National Organ Donation and Transplantation Committee, admitted to Chinese domestic media in 2013 that “90% of the doctors do not know how brain death works.”Footnote 39 Thus, it is likely that the authors used the term “brain death” only as pretext to cover up the real organ source because the organ sources were illegal.

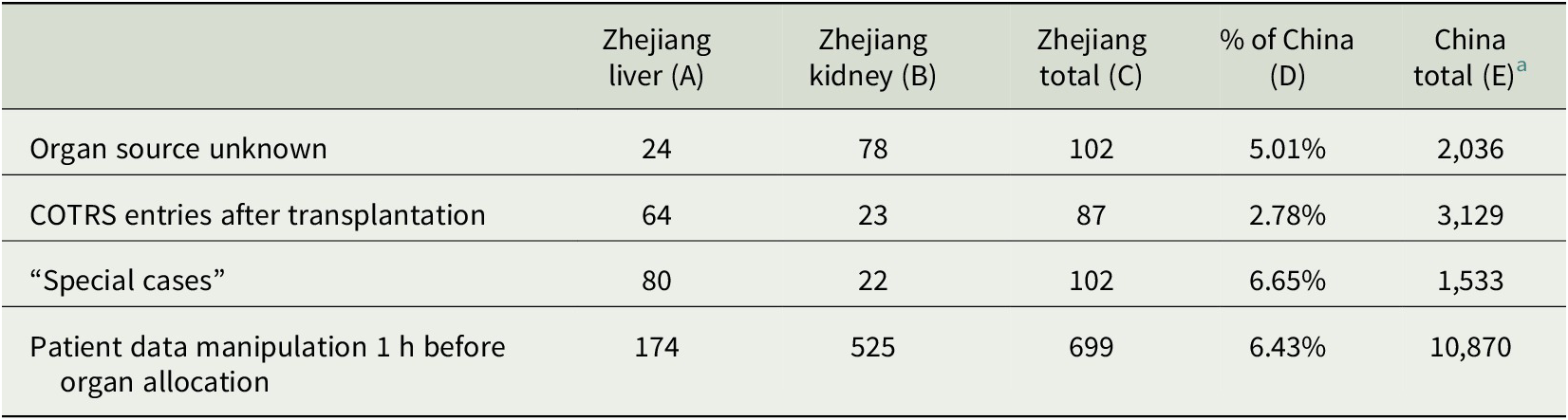

Recent evidence indicates that a considerable amount of the organs used for transplantation in China are still obtained via illegal ways. Since 2015, all organs for transplantation in China must come from the national organ allocation system, the China Organ Transplant Response System (COTRS). All other organs are illegal. However, a leaked COTRS internal data verification report revealed that a quite large number of transplant organs were not from COTRS, that is, were illegal transplants.Footnote 40, Footnote 41 The report cross-checked the data from COTRS with the China Liver Transplant Registry (CLTR) and Chinese Scientific Registry of Kidney Transplantation (CSRKT). In the time range from January 2015 to April 2018, 102 transplants performed in the Zhejiang Province were not allocated from the COTRS, and per definition, these were illegal organ transplants (Table 2). In the whole of China, more than 2,000 transplants were found to be from “unknown” sources. In more than 10,000 cases, patient data in the COTRS were manipulated 1 h before organ allocation (Table 2). The above-mentioned transplants with unknown source are only those reported to CLTR or CSRKT. It is conceivable that more illegal transplants were not reported to these registries and remained unidentified by the COTRS data verification reports. Thus, the real number of illegal organ transplants must be much higher than that summarized in (Table 2). A systematic investigation into organ donation from claimed brain-dead donors is warranted.

Table 2. Selected Results from the China Organ Transplant Response System (COTRS) Data Verification Report Zhejiang Province (January 1, 2015 to April 13, 2018)

a The leaked report contains data from Zhejiang Province (columns A, B, C, and D). China totals (column E) were extrapolated (E = C/D) by the authors of the present article.

Conclusion

Chinese medical professionals have developed brain death determination guidelines in the absence of brain death legislation. Encouraging progress in brain death determination practice has been reported from China. Chinese criteria were even more robust than those in the United States. At the same time, the brain death definition appears to be abused by individuals for organ harvesting and to cover up the illegal organ sources. In such cases, it was obvious that a brain death determination was not carried out and the “donors” were simply declared to be brain dead. To obtain international credibility and to obtain trust from patients, China must honestly and seriously identify and combat the organ crimes in its transplant system. Only in this way can China’s transplant medicine gain the respect it aspires.

Acknowledgment

This work was partly supported by the grant Graduiertenkolleg (GRK) 2015/2 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), Bonn, Germany.