Long-distance overland travel has been historically important across the globe where groups of people and caravans of travellers, traders and pilgrims passing through rural areas have been the norm. Travellers need safe and hospitable places to obtain supplies, rest and information while moving across less familiar places. From Eurasian contexts, for instance, travel stopovers, including small countryside caravanserai (‘caravan hall’), were founded in rural areas on roads or paths between towns (Franklin & Boak Reference Franklin, Boak, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Johansen Reference Johansen2016; Shokoohy Reference Shokoohy1983). These small stopovers in peripheral areas consisted of settlements, structures for storage and sleeping, public spaces and water sources (Yavuz Reference Yavuz1997). Rural stopovers, like the caravanserai, have also been important for trade and their religious shrines for collective ceremonies. Importantly, the small rural stopovers frequently have fortifications, resting areas, storage, plazas for exchange and interaction, and religious buildings, which were important for travellers (Shokoohy Reference Shokoohy1983; Thareani-Sussely Reference Thareani-Sussely2007). While many stopovers continuously functioned as barracks for safe lodging (Nielson Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nossov Reference Nossov2013), some eventually became small settlements due to their importance for trade, ritual, safety and social interaction among various groups traveling long distances across the countryside (Núñez & Briones Reference Núñez, Briones, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Palka Reference Palkain press). These sites are not ports, entrepots or secondary trading centres since they are not primary settlement or market nodes in a regional economy, nor do they have the demographic size, developed market-places and political connections with the population centres of ports (Alexander Reference Alexander, Kepecs and Alexander2005; Andrews Reference Andrews and Liendo Stuardo2008; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Franklin & Boak Reference Franklin, Boak, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Polanyi Reference Polanyi1963). Stopovers are placed along interior trade routes in rural areas and do not have the large amounts of diverse exotic goods of the trading ports (Clark Reference Clark2016). Stopovers also differ from pilgrimage centres (Palka Reference Palka2014) since they have more permanent habitation, fewer religious buildings, more storage facilities and more defensive capabilities. Stopovers are also larger and have bigger buildings and more permanent residents when compared to travellers’ camps, resting places and depots (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021). Small rural stopovers are more like way stations, outposts or caravanserais that were loosely connected through subsidiary routes to ports of trade and demographic centres in regional trade networks (Berenguer Reference Berenguer, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Edwards Reference Edwards, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Mader et al. Reference Mader, Reindel, Isla, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Siveroni Reference Siveroni, Clarkson and Santoro2021). In colonial period Mesoamerica, some of these small indigenous rural sites with habitational structures and shrines became Spanish parajes, paradas and estancias maintained by local communities for travellers visiting markets, political centres and pilgrimage centres. These sites were located either on main roads or informal routes and paths (caminos, corredores, vías, senderos) across the realm (Bonilla Palmeros Reference Bonilla Palmeros2020; Lee & Navarrete Reference Lee and Navarrete1978; Long Towell & Attolini Lecón Reference Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010). One such rural stopover at Late Postclassic to early historic (c. ad 1350–1650) Maya sites at Mensabak in Chiapas, Mexico, is discussed below in comparative context (Fig. 1). I construct a model for specific human behaviours at rural stopover sites that have archaeological correlates and anthropological significance.

Figure 1. Location of Mensabak and its archaeological sites in the Sierras of Chiapas, Mexico, between Tabasco on the Gulf Coast and Soconusco on the Pacific Ocean. (Map: Santiago Juarez and Joel Palka.)

Importantly, the locations and material culture of rural stopovers make them archaeologically visible. Small rural stopover places have not been studied as often historically and archaeologically as larger trading ports, rural centres and pilgrimage shrines, but they can be examined with surveys and excavations by archaeologists conducting complete ground truthing in the countryside (Berenguer Reference Berenguer, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Erickson-Gini & Israel Reference Erickson-Gini and Israel2013; Jiménez Gómez Reference Jiménez Gómez, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Palka Reference Palka2014). Historical accounts provide information regarding the locations, nature, economic structure and social implications of these interesting sites (Jiménez Gómez Reference Jiménez Gómez, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Morante López Reference Morante López, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010). However, we often lack detailed historical descriptions of the stopovers and life within them because chroniclers usually do not describe small rural settlements. Historical information on Maya travel routes and rural sites have been used to reconstruct regional interaction and economies (Caso Barrera Reference Caso Barrera2002; Feldman Reference Feldman2000; Woodfill Reference Woodfill2019), but we know less about stopover sites in countryside and lifeways there. Archaeology and comparative analyses help fill this informational gap. In this article, I place rural stopovers in an anthropological context and discuss salient human behaviours at these kinds of sites with the archaeological case study of Mensabak, Chiapas, Mexico.

Stopover sites in comparative analysis

Cross-culturally, small rural stopovers have existed in societies practising long-distance mercantilism, overland travel and pilgrimage between religious shrines. People require places to stop safely between the more populous towns and they need sustenance and crucial information about hostile regions. European traders, for instance, safely lodged in small rural Islamic caravanserais because of the economic importance and protection of local merchants there (Burns Reference Burns1971; Burton [1893] Reference Burton1964). In Mesoamerica, some small stopovers were incorporated into ritual landscapes, many with rock-art shrines, along distant trade routes that drew in local people, merchants, pilgrims and travellers for collective exchange, rituals and social ties (Pye & Gutiérrez Reference Pye, Gutiérrez, Lowe and Pye2007; Reyes Esquiguas Reference Reyes Esquiguas, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010, 620). The group rituals helped people feel secure and they promoted success in travel, social interaction and trade from the assistance of resident deities and local inhabitants (Dibble & Anderson Reference Dibble and Anderson1959; Palka Reference Palka2014). Subsequently, at small rural stopover sites people joined in trade, ceremony, protection and social solidarity, making them cross-culturally significant for human settlement and interaction. Hence, the investigation of rural stopovers carries important anthropological and material insights into human behaviour regarding travel, economic interaction, religious ritual and social cohesion among people trekking in the countryside. Archaeology is significant for this endeavour since these often neglected sites can be excavated to learn about them and human behaviours associated with them.

To date, archaeological, historical and anthropological studies of travel have concentrated on roads, connections between centres, economic organization and phenomenology (Candy Reference Candy2009; Franklin & Boak Reference Franklin, Boak, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984; Núñez & Briones Reference Núñez, Briones, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Rueda Reference Rueda, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Trombold Reference Trombold1991; Van Dyke Reference Van Dyke2007). Investigations of travel routes routinely focus on main routes and site locations—typically towns—and connections between them, along with reconstructions of trade and economic behaviours (Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). Scholars often look at pragmatic considerations, such as travel times, strategic town placement and the geographical organization of travel sites (Gorenstein & Pollard Reference Gorenstein, Pollard and Trombold1991; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). Other investigators theorize on the function and social importance of travel and trade sites, including ports of trade, market centres, trade diasporas, international trade centres, storage facilities and gateway communities (Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Gallareta Negrón, Robles Castellanos, Cobos Palma and Cervera Rivero1988; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Clark Reference Clark2016; Edwards Reference Edwards, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Gasco & Berdan Reference Gasco, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003; Hirth Reference Hirth1978; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Polanyi Reference Polanyi1963; Stein Reference Stein1999).

Yet small rural travel stopovers, traffic ports, outposts and caravanserais on less-travelled paths and their social and economic importance have not received adequate treatment in travel and settlement studies (Long Towell & Attolini Lecón Reference Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978; Nossov Reference Nossov2013; Yavuz Reference Yavuz1997). However, investigations are increasing regarding human interaction and behaviour at caravan campsites, rest areas, small rural centres, oases and caravanserais on secondary routes through ethnoarchaeology, ethnohistory and archaeological excavations (Darnell Reference Darnell, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Mader et al. Reference Mader, Reindel, Isla, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Núñez & Briones Reference Núñez, Briones, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Palka Reference Palka2014; Siveroni Reference Siveroni, Clarkson and Santoro2021). Economic and political power structures also are important at these rural places, which can be managed locally or sometimes impacted by state polities (Darnell Reference Darnell, Clarkson and Santoro2021). For comparative purposes here, small travel stopovers in rural Mesoamerica were similar to Eurasian caravanserais and Andes outposts (Mader et al. Reference Mader, Reindel, Isla, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 178; Siveroni Reference Siveroni, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 114). Their similar economic, religious and integrative characteristics were practical for travellers and important for social cohesion.

Characteristics of small rural stopovers

Across the Old World, caravans and groups of people covering hundreds of kilometres in rural areas needed safe places to stop so traders, travellers and pilgrims could rest, acquire food and water, exchange goods and make religious offerings. In the particular cases of Eurasian caravan stopovers, including caravanserais, they were dispersed in the countryside far from towns (Fig. 2; Johansen Reference Johansen2016; Shokoohy Reference Shokoohy1983). Many were commonly known destinations along principal (formal) or less-travelled (informal) long-distance routes (Bryce et al. Reference Bryce, O'Gorman and Baxter2013; Clarkson & Fowler Reference Clarkson, Fowler, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Trombold Reference Trombold1991) since people seeking hospitable stopovers required rest and crucial information on where they could safely venture. Importantly, religious shrines united the travellers in collective ritual due to the uncertainties and dangers of rural travel (Bryce et al. Reference Bryce, O'Gorman and Baxter2013; Johansen Reference Johansen2016; Shokoohy Reference Shokoohy1983). Travellers need to communicate with spiritual forces through ritual for the well-being of people and their goods, and for the success of the trip (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 20, 26–8, 32–3). These rituals have taken place at landscape altars, temples in settlements and rock-art sites. After collective rituals, travellers shared meals, interacted socially and exchanged information (Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 28–9).

Figure 2. Example of rural caravanserai stopover, landscape shrines, and fortified public area, Fars Province, Iran: Izadkhast caravanserai, seventeenthth century. (Photograph: Bernard Gagnon, Wikipedia commons.)

Other desirable characteristics of small rural stopovers included their small markets and receptive local populations where traders exchanged goods and economic information (Yavuz Reference Yavuz1997). The stopovers led to interaction between people who did not have kinship ties and who were not united in cultural practices, ethnicity, or political affiliation (Bryce et al. Reference Bryce, O'Gorman and Baxter2013; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 35; Núñez & Briones Reference Núñez, Briones, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 222–3). For example, rural stopovers with their hospices, markets, water and shrines, such as ‘travel villages’, ritual rock cairns, ecclesiastical estates and caravanserais, were valuable for the solidarity and safety of the multinational travellers on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela (Candy Reference Candy2009, 42-7, 60–61, 80–81). Clearly small rural stopover places helped different groups of people form social bonds and allowed them successfully to undertake their travels, trade and religious worship across the world.

Central elements of stopover sites include their placement along rural trade routes, small settlements, water availability, structures for storage and sleeping, fortified safe havens, public religious shrines, ritual landscapes and social places for small-scale trade of exotic goods (Dale Reference Dale1994; Edwards Reference Edwards, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Mader et al. Reference Mader, Reindel, Isla, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Thareani-Sussely Reference Thareani-Sussely2007). Frequently, rural stopovers are politically autonomous. These sites, too, can managed by local governments that may be loosely connected to regional states (Darnell Reference Darnell, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 30). However, sometimes they can actually be controlled by regional polities if they are on main trade or pilgrimage routes (Edwards Reference Edwards, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Franklin & Boak Reference Franklin, Boak, Clarkson and Santoro2021). Burton ([1893] Reference Burton1964, 253–5) describes some of these attributes at a rural small site, Al-Hamra, found on an alternate route to Meccah:

It [Al-Hamra] is built on a narrow shelf at the top of a precipitous [defensible] hill … [here] water of good quality is readily found … Al-Hamra is a collection of stunted houses made of unbaked brick. It appears thickly populated in the parts where the walls are standing … It is well-supplied with provisions … The bazar [market] is a long lane, here covered with matting … Near the encamping ground of caravans is a fort for the officer commanding a troop of Albanian cavalry, whose duty is to defend the village, to hold the country, and to escort travellers.

Archaeologically, such rural stopovers can be recognized as small clusters of structures near springs or rivers with reduced market spaces and few habitational structures, some of which were fortified (Berenguer Reference Berenguer, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Bryce et al. Reference Bryce, O'Gorman and Baxter2013; Burns Reference Burns1971; Franklin & Boak Reference Franklin, Boak, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Núñez & Briones Reference Núñez, Briones, Clarkson and Santoro2021). Additionally, these sites can be found along travel routes on maps and aerial photographs, in travellers’ accounts and through survey in rural areas between centres. Small caravanserais along the Silk Road and trade routes in Iran, for instance, have drawn the attention of art historians and archaeologists examining their constructions, functions and local religious life (Erickson-Gini & Israel Reference Erickson-Gini and Israel2013; Johansen Reference Johansen2016).

For the Americas, one historical and archaeological example of a stopover in the countryside is the Inca site of Cajamarca, Peru. Cajamarca was a small town founded by local indigenous people that became a stopover (tambo or tampu, ‘resting place’) on the Inca road far north from the capital of Cuzco (Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984, 56–61; Julien Reference Julien1993). Elites supported these rural tambos, or estancias, for officials’ journeys, that were central for storage, rest, and the movement of people and goods along the extensive Inca road system (Garrido Reference Garrido2016; Hyslop Reference Hyslop1984). Local indigenous populations resided at Cajamarca to maintain its buildings, storage facilities, plaza, temples and structures for Inca nobles and Spaniards when they travelled with their caravans. People stayed in the site's buildings or in tents. Water was available for travellers and adjacent hot springs served as baths. Goods were exchanged at the site, especially in its plaza that was fortified. Additionally, a hilltop fortress was found close by if violence broke out in this rural area. Travellers, too, undertook rituals in the plaza and adjacent temples (Julien Reference Julien1993, 252). On Andean travel routes, rock-art shrines were important for collective rituals on the landscape at rural stopover sites and along rural routes (Berenguer Reference Berenguer, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Mader et al. Reference Mader, Reindel, Isla, Clarkson and Santoro2021; Nielsen Reference Nielsen, Clarkson and Santoro2021, 32).

One archaeological example of a rural Mesoamerican stopover is the ancient site of Los Horcones, which rests on the Pacific coast of Chiapas between major ancient economic and political centres. People established this protected site on an impressive hill with shrines, some with rock art, located along a trade and travel route in this coastal cacao-growing area. Los Horcones has temples and ballcourts for collective community rituals, numerous buildings for sleeping and storage and enclosed plaza areas for trade and social interaction between local people and traders. The stone monuments, ceramics and architecture at the site point to strong ties with people from the Classic-period (c. ad 300–500) metropolis of Teotihuacan in Central Mexico (Garciá-Des Lauriers Reference García-Des Lauriers, García-Des Lauriers and Love2016). People were moving between Teotihuacan, sites in Veracruz, the lowland Soconusco cacao area in Chiapas and coastal Guatemalan towns. Monuments depicting war gods in addition to enclosed plazas on elevated areas point to the defence of the site's inhabitants. The large percentage of green Pachuca obsidian (about 40 per cent of the assemblage) brought from Central Mexico to Los Horcones underscores the strong ties with Teotihuacan merchants travelling to the Chiapas coast for trade in obsidian and cacao beans. Long-distance trade and travel across Mesoamerica and the setting up of stopovers and ritual landscape shrines with unified iconography (and rock art) along overland routes had existed for centuries (Pye & Gutiérrez Reference Pye, Gutiérrez, Lowe and Pye2007), but we have few details regarding everyday life at these rural places. Fortunately, scholars have documented comparative travel sites and trade routes from historic documents and archaeological survey in Mesoamerica (Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Long Towell & Attolini Lecón Reference Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). Their insights are important for understanding ancient stopover sites at Mensabak and elsewhere.

Mesoamerican trade caravans and stopover sites

Long-distance travel for trade and pilgrimage with human caravans in Mesoamerica was widely documented following the Spanish conquest (Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Clarkson & Fowler Reference Clarkson, Fowler, Clarkson and Santoro2021). Large numbers of people travelled along routes through mountains and forests across political boundaries. The travellers included merchants, pilgrims, political officials, migrants, tribute collectors, warriors, spies and porters. In these rural areas, travel was often hazardous (Dibble & Anderson Reference Dibble and Anderson1959; Viqueria Reference Viqueira2002, 119, 147). Some settlements were not always friendly to outsiders. Hence, local governments, merchants and soldiers helped maintain small rural settlements for safety along the long routes. Ports of trade, trading diasporas, towns and small stopover sites in between were developed to facilitate trade and travel to central economic destinations. Sites with markets and pilgrimage shrines were more accepting of travellers and strangers due to social interaction and the importance of peaceful trade (Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Gaxiola González Reference Gaxiola González, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010). In Chiapas, Aztec and Maya merchants crossed the region exchanging their wares and travel information. These merchants organized human caravans and negotiated trade in foreign areas as part of their specializations (Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957, 115; Clarkson & Fowler Reference Clarkson, Fowler, Clarkson and Santoro2021).

Mesoamerican historical chronicles provide evidence for long-distance travel routes and their small rural stopovers. Some of the better-described historic routes are found in southern Mexico (Attolini Lecón Reference Attolini Lecón, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; Dibble & Anderson Reference Dibble and Anderson1959; Viqueira Reference Viqueira2002). However, smaller radial routes in rural areas off the main roads connected towns and stopovers (Rueda Reference Rueda, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Sheseña et al. Reference Sheseña, Lozada, Tovalín and Cruz2021), but they are not as well described as the main routes. Colonial period maps from Chiapas (Fig. 3) show several possible paths and rural stopovers and not just large centres (Lee & Navarrete Reference Lee and Navarrete1978, 78, 96, 103). One extensive rural route went through several towns, farmsteads (ranches, estancias) and resting places (parajes) ranging between one and four leagues apart (around 5–20 km; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978, 77–84). It was important for merchants to reach rest points at the ranches and small stopovers along these overland routes so they could safely exchange their products with local populations (Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). For instance, roads, paths, ritual sites and stopovers connected centres in Guerrero, Oaxaca and central Chiapas with the Pacific coast Aztec province of Soconusco (Xoconochco; Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Pye & Gutiérrez Reference Pye, Gutiérrez, Lowe and Pye2007), which was critically important for the trade in cacao and other regional products.

Figure 3. Colonial period map showing towns and stopovers along routes in Soconusco on the Pacific Coast of Chiapas, Mexico. (From Navarrete Reference Navarrete, Lee and Navarrete1978, 78, fig. 16, courtesy of the New World Archaeological Foundation.)

One account mentions rural stopovers along a rural Chiapas route:

the road passes through valleys with few inhabitants and since the traffic does not earn enough to permit the carrying of forage and provisions, settlements sprung up at 8 km. or so intervals to feed the men and animals; their aspect and function are determined completely by the traffic. These serve for resting and staying overnight. (Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978, 83)

Catholic priests also helped maintain and integrate the routes and their travellers by creating churches, shrines and missions at stops along them (Viqueira Reference Viqueira2002, 125–34). The colonial governments ensured their protection and viability. Therefore, these rural stopovers had important economic, religious, political and social functions for the caravans.

In Spanish conquest-era Chiapas, caravan trade and travel routes crossed extremely rural areas since highly prized Aztec and Maya products, including cacao, tobacco, feathers, incense and amber, were available here (Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978; Viqueira Reference Viqueira2002). Aztec pochteca merchants traded green Pachuca obsidian, copper bells and cotton cloth for these highly sought Maya items (Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Dibble & Anderson Reference Dibble and Anderson1959). Importantly, Aztec merchants established garrisons and trade enclaves at Zinacantan (Zinacantlan) in the highlands and in their cacao-growing province of Soconusco on the Pacific coast to protect their caravans (Kohler Reference Kohler, Lee and Navarrete1978). Similar caravans of Maya traders crossed the area, which was not always safe due to the politically fragmented landscape with its violence, random trade taxation and piracy. Aztec and Maya traders also maintained markets and garrisons on the Gulf Coast, which were connected economically and socially with trade towns and small rural stopovers in Chiapas (Attolini Lecón Reference Attolini Lecón, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957). Travel routes ran through the Chiapas highlands connecting this region with the Gulf Coast to the north and with Aztec Central Mexico and the Guatemalan highlands (Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Lee Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). Another important route was through the countryside along the Pacific Coast of Chiapas that continued to Oaxaca and Central Mexico (Attolini Lecón Reference Attolini Lecón, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Feldman Reference Feldman1985). An additional rural route passed through the towns of Zinacantan and Comitan (near San Cristobal or Ciudad Real) heading north to the lowlands and Gulf Coast via Ocosingo (Ocosinco) in Chiapas (De Vos Reference De Vos1980; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978; Taladoire Reference Taladoire2016). Modern roadways follow these ancient rural routes; one secondary road from Ocosingo to Palenque passes near Mensabak, as discussed below (see Figure 3). Another less-travelled path incorporated the rural Ch'ol Maya towns to Tumbalá and Tila, which had pilgrimage shrines, ritual caves with paintings (rock art) and market areas that integrated travel, commerce, religion and different social groups (Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2015; Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978, 93).

Significantly, Acalan (‘Place of [Trading] Canoes’) Chontal Maya merchants of the Gulf Coast of Tabasco supported the criss-crossing trade routes through the countryside that connected their lands with Central Mexico, Guatemala, Yucatán and Honduras (Attolini Lecón Reference Attolini Lecón, Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957). These Chontal Maya actively maintained exchange ties with Maya and Zoque peoples in the rural sierras of Chiapas to the south to provide their markets with exotic bird feathers, animal pelts, incense and tobacco (Navarrete Reference Lee, Lee and Navarrete1978). Tenosique (Tanoche or Tanosic), Tabasco, played a major role in these economic interactions since the small town, which was jointly occupied by Chontal and Yucatec Mayas (also Aztecs intermittently), is located where the Usumacinta River is first navigable downriver to the Gulf Coast (De Vos Reference De Vos1980). One overland secondary route connected Tenosique with Ocosingo, which Maya from Mensabak (perhaps called Nohha; De Vos Reference De Vos1980) used to visit these towns (Fig. 4). Another path followed valleys from rural Mensabak towards the large Ch'olti’-Lacandon settlement of Lakamtun at Lake Miramar just to the south. This informal route was linked to a path from Palenque and Tumbalá to the Lake Miramar settlements through Pochutla on Lake Ocotal Grande (Fig. 4; Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2015; De Vos Reference De Vos1980). Significantly, Mensabak rests right on the crossroads of the rural Ocosingo to Tenosique and Tumbalá/Palenque to Ocotal/Miramar routes (De Vos Reference De Vos1980, 507, 510). Historic Lacandon Maya from Mensabak actually travelled along these informal paths to Palenque, Ocosingo and Tenosique to trade their tobacco for salt, cloth and metal tools until recently (Palka Reference Palka2005; Reference Palka, Schwartzkopf and Sampeck2017). The documentary evidence regarding trade and travel routes, in addition to archaeological data, indicates that Aztec and Maya merchants and travellers walking the countryside between the Gulf Coast, Zinacantan in the highlands, and then to Soconusco on the Pacific Coast, used Mensabak as a rural stopover site because of its special geographical, social, ritual and economic characteristics. Hence, this site provides an ideal archaeological case study to examine social life at these sites.

Figure 4. Possible rural travel routes in Late Postclassic (c. ce 1500) Chiapas as optimal routes calculated in GIS. (Map: Josuhé Lozada Toledo, courtesy of the Mensabak Project.)

Case study: a small rural stopover at Mensabak, Chiapas

Long-distance overland travel stopovers can be examined through archaeology for insights on specific human behaviours associated with them. Their characteristics, especially their locations on rural travel routes, abundant water, buildings for sleeping and storage, fortifications for safety, trade in exotic items, small populations and public religious shrines can be identified through survey, excavation and artifacts. Postclassic sites dot the Tabasco plain (Scholes & Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1968), but few coeval sites have been encountered in adjacent northern Chiapas, including along the Usumacinta and Tulijá river routes (Palka & Lozada Toledo Reference Palka, Lozada Toledo and Linares Villanueva2018). One site was discovered along a secondary long-distance travel, trade and pilgrimage route at rural Mensabak, Chiapas, Mexico (Palka Reference Palka2014). Mensabak (also Mensäbäk) is a small cluster of archaeological sites at a small lake located in the Sierras of Chiapas, about 250 km to the south of the lowland coastal Maya and Aztec trade enclaves and port towns of Potonchan and Xicalango (Xicalanco) on the Gulf Coast of Tabasco (Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957; see Figure 1). The sites and shrines at Mensabak were discovered during the author's collaborative rural archaeological surveys with local Lacandon Maya from Puerto Bello Mensabak (Palka Reference Palka2014; Palka et al. Reference Palka, Sánchez and Lozada2020). We research an area far from regional Maya centres and ports, which have drawn more archaeological attention due to the presence of Maya elite material culture like palaces and hieroglyphic monuments. Mensabak is a rural stopover site with multiple communal rock-art shrines, canoe ports, plazas and several protected settlements spread out along the shore of a small lake. The Mensabak site as a whole acted as a safe haven, religious sector and small-scale market area. Mensabak also has plentiful water from its lakes, springs and streams along with abundant foods from the waters, fields and forests for residents and travellers. Mensabak did not function as a trading port since it is not located on main travel routes managed by regional polities. Hence, the adjacent lakeside settlements, plazas and shrines here functioned together as a rural stopover; there was not just one central site or port.

Two small settlements dating to around the time of Spanish colonization (Late Postclassic to early historic times: c. ad 1350–1650) were founded by rural Maya leaders and their allies at Mensabak (Palka Reference Palka2014). The two settlements, Tzibana and La Punta, were placed on fortified peninsulas on the lake shore by Maya elites and merchants to attract travellers, traders and pilgrims. Both sites have large canoe ports where travellers docked their canoes, unloaded their goods and sought food, shelter and social interaction. Diagnostic Late Postclassic ceramic types are found at these sites, including Matillas Fine Orange wares from the Chontal Maya Gulf Coast, in addition to small footed bowls and colanders (Fig. 5). Maya lineages and their allies migrated to Mensabak specifically because of the culturally significant pilgrimage shrines located there (Palka Reference Palkain press). Mirador Mountain (also El Mirador), an impressive, unusual mountain with a sheer, red-stained cliff rising out of the lake, dominates the Mensabak landscape (Fig. 6). Maya travellers arrived at a canoe port at the Ixtabay temple complex (see Figure 1) and ascended this mountain for rituals at a stone-block temple near a cave on its summit. This ‘water mountain’ with temples on an island in an idyllic lake recalls the Aztec mythological/historical homeland of Aztlan and altepetl (‘community’). Mirador Mountain even has a spring that initiates a major river (the Río Tulijá) recalled in Aztec Aztlan myths. Maya and Aztec pilgrims, Aztec pochteca and Maya merchants and travellers arrived at Mensabak where they ascended Mirador Mountain to conduct ceremonies at landscape shrines here. They also performed collective rituals with the local community at nearby landscape and public rock-art shrines.

Figure 5. Late Postclassic Maya ceramics from Mensabak: (a) stamp representing Mirador Mountain (upside down); (b) small bowl; (c) colander fragments; (d–e) Matillas Fine Orange trade wares. (Figure: Rubén Nuñez, courtesy of Mensabak Project.)

Figure 6. Mirador Mountain in an Aztlan-like lake setting at Mensabak, Chiapas, Mexico. (Photograph: Joel W. Palka.)

One site, La Punta, is protected with defensive walls and residences along the lakeshore every 4–6 metres, like bastions (Fig. 7). An artificial stone-block island (Str. 11) provided a check-point at the canoe port entrance. The large, well-formed canoe port was the focal point of this settlement, enhancing its function as a stopover site. Storage buildings (Strs. 4, 8 and 57), public structures (Strs. 3, 58 and 59) near a small plaza for unloading and gathering (Strs. 60 and 61) and residences (Strs. 10, 12, 66 and 67) were located around the canoe port. A stairway from the canoe port rises to a large structure compound (Strs. 2 and 9) on a small plaza with a central altar and stela for ceremonies. Some traders and pilgrims went up the stairs to join local leaders in collective ritual feasts and to exchange goods in the plaza. Buildings on the plaza and on the site's hilltop shrine near cliffs (Strs. 51 and 55) were aligned to the temple and cave on Mirador Mountain, enhancing the site's religious importance. The hilltop shrine's plaza would have held numerous ritual participants, which indicates its communal function.

Figure 7. La Punta, Mensabak. Note the walls and structures protecting the perimeter, canoe port, plaza and hilltop shrine. (Map: Joel Palka.)

Archaeologists recovered large amounts of animal bone from feasting and some trade goods on the plaza (Palka Reference Palka2014). The trade goods included a small amount of Matillas Fine Orange ceramics produced by Chontal Maya in Tabasco, a marine shell bangle from Soconusco (Voorhies & Gasco Reference Voorhies and Gasco2004), a few copper bells from Central and West Mexico (Hosler Reference Hosler1994) and many green obsidian blades (about 40 per cent of the obsidian artifacts) from the Pachuca source in Central Mexico, brought by Aztec pochteca merchants (Fig. 8; Berdan et al. Reference Berdan, Masson, Gasco, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Lee, Salcedo and Voorhies1989; Smith Reference Smith1990). Sites located along Aztec travel and trade routes and colonies along the Pacific Coast in southern Mexico, such as Tututepec, Oaxaca and Ocelocalco in Soconusco on the Chiapas Pacific coast, typically contain a large quantity (over 30 per cent) of Pachuca obsidian (Braswell Reference Braswell, Smith and Berdan2003; Clark & Lee Reference Clark, Lee, Lowe and Pye2007; Clark et al. Reference Clark, Lee, Salcedo and Voorhies1989; Levine et al. Reference Levine, Joyce and Glascock2011; Ohnersorgen Reference Ohnersorgen2006; Smith Reference Smith1990). Most Late Postclassic sites in Chiapas have low quantities (less than 10 per cent) of green Pachuca obsidian. Aztec Nahuatl terms also appear in the local Lacandon Mayan language and in historic Maya groups in the region (De Vos Reference De Vos1980), pointing to significant long-term interaction with Aztec people. Small quantities of Central Mexican copper bells also occur in households at other Mensabak settlements, underscoring their importance in inter-regional trade and ritual. It is possible that Aztec pochteca merchants visited Mensabak and its Aztlan-like Mirador Mountain, since the site rests along a rural route between their garrisons on the Gulf Coast, Zinacantan in the Chiapas highlands and Soconusco. Traders probably acquired local tobacco, animal skins and feathers, which were prized in Postclassic times, including in Central Mexico (Palka Reference Palka, Schwartzkopf and Sampeck2017). Moreover, Maya merchants from Tabasco also arrived at Mensabak, since they actively participated in the trade and ritual life involving Aztec pochteca in this region. La Punta was a safe residential site, a place for storing goods, a setting for communal feasting and a stopover for travellers to interact, trade and perform rituals with local political leaders and inhabitants.

Figure 8. Long-distance Late Postclassic trade items from La Punta, Mensabak: (top left) Chontal Maya Matillas Fine Orange ceramic from Tabasco; (top right) marine shell bangle from Soconusco; (lower left) Aztec green Pachuca obsidian from Central Mexico; (lower right) copper bell from Central or West Mexico. (Photographs: Joel Palka.)

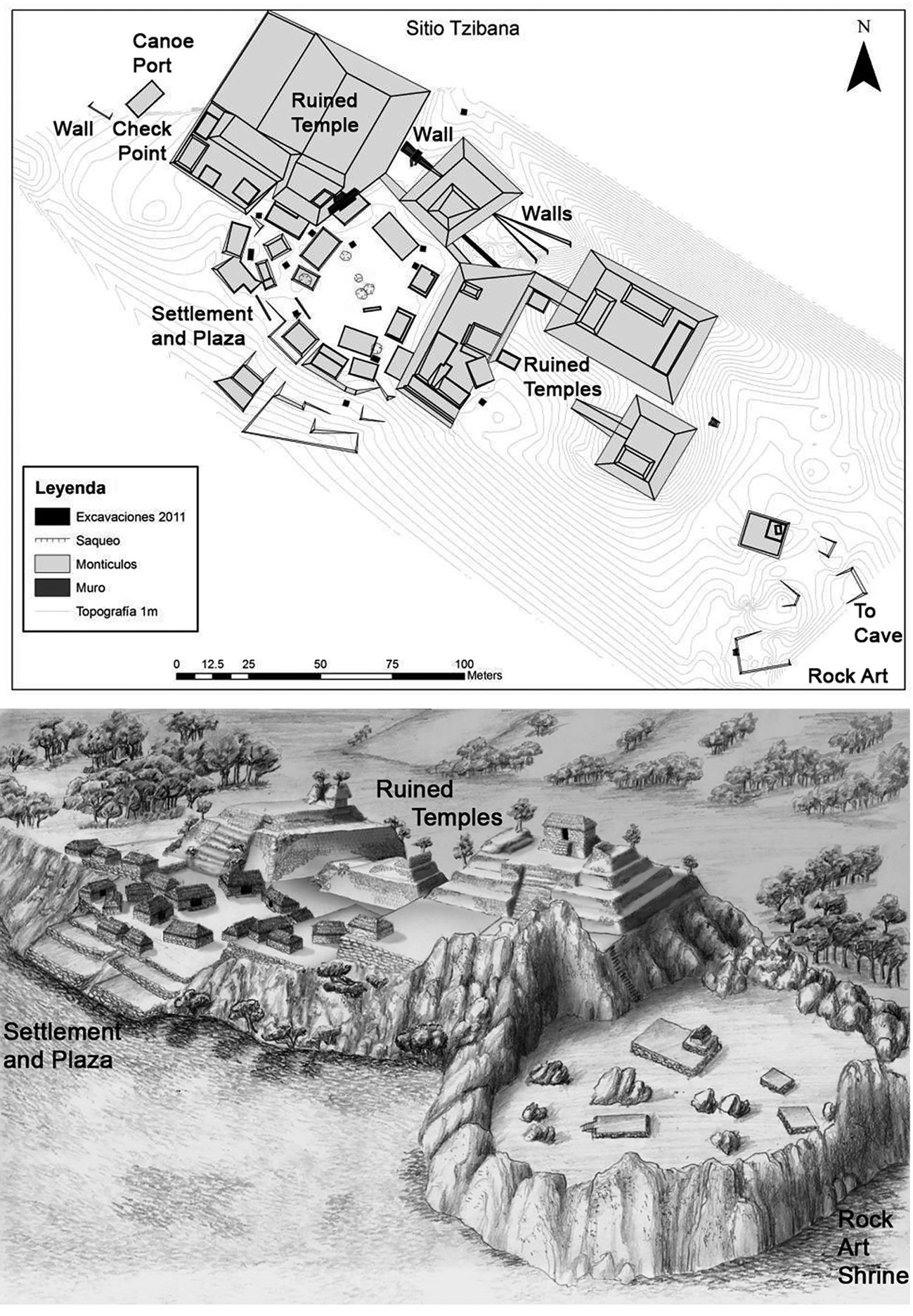

Another Mensabak settlement, Tzibana (also Tz'ib’ana), is a small site across the lake from La Punta with a large plaza surrounded by a cluster of buildings and defensive walls uphill from its large canoe port (Fig. 9). A defensive wall blocks access to the site from the canoe port. Important Maya families resided at Tzibana, which is evidenced by the presence of large Late Postclassic residences made of finely dressed blocks. The site has only a few residential structures, but their sizable construction and architectural complexity point to the wealth of the inhabitants, which was probably gained through trade. Travellers were drawn to Tzibana because of its important Maya families, ample plaza, location near water and the Late Postclassic ceremonial shrines at ruined ancient temples, a nearby cliff with rock art rising from the lake (Fig. 10) and a large lakeside cave, which was full of ritual materials. The multitude of rock-art designs, including hunting scenes, animal totems or spirit familiars and hand prints of men, women and children (Palka & Lozada Toledo Reference Palka and Lozada Toledo2022), speak to the communal nature of the rites at the cliff. Additionally, the numerous human burials and utilitarian ceramics in the cavern behind the cliff also evidence the ceremonial involvement of the community and not just a few religious specialists or elites. Postclassic people did not construct residences on the tall Preclassic (c. 200 bc–ad 200) temples, but they may have used them for public rituals and feasts according to sporadic finds of broken ceramics and animal bone on their surfaces. Whereas La Punta was a political and economic hub at Mensabak, the inhabitants of Tzibana demonstrated their families’ wealth and their abilities to conduct collective ceremonies at important shrines to visitors. The travellers were likely to have used the many residential and storage structures around its plaza where trade was conducted. Traders brought small quantities of Chontal Maya Matillas Fine Orange ceramics from Tabasco, Mexican copper bells and exotic marine shell. Furthermore, they exchanged a large percentage (about 35 per cent) of Central Mexican Pachuca green obsidian, pointing again to the presence of Aztec traders, or their direct influence on Chontal Maya merchants, in the local economy as historically and archaeologically seen in Chiapas and nearby Oaxaca (Clark et al. Reference Clark, Lee, Salcedo and Voorhies1989; Levine et al. Reference Levine, Joyce and Glascock2011). Hence, Tzibana was the secure locale for the exchange of goods and collective rituals at religious shrines. It is likely that a small number of travellers rested at Tzibana before continuing on their journeys.

Figure 9. The Late Postclassic Tzibana site, Mensabak. Note the protective walls, canoe port, plaza and ruined Maya temples as shrines. (Above: map by Rebecca Deeb and Chris Hernandez; below: drawing by Santiago Juárez, courtesy of the Mensabak Project.)

Figure 10. Tzibana rock-art shrine on a lakeside cliff at Mensabak, Chiapas. (Photograph: Joel Palka.)

Other comparable Postclassic Maya sites in Chiapas and nearby Petén, Guatemala, differ from what we have seen at the Mensabak rural stopover. For instance, the large island site of Topoxte in Petén was a town with large stone block temples and palaces (Wurster Reference Wurster2000). Topoxte was a political centre of the Kowoj Maya polity that interacted with the nearby regionally powerful Itza Maya and their many sites of the Petén Lakes area (Rice & Rice Reference Rice and Rice2009). Another example, the large site of Canajaste in highland Chiapas was strongly fortified and not very accessible, and it had a large population comparable to other contemporaneous centres in the region (Blake Reference Blake2010). Canajaste Maya interacted with adjacent populations along the trade corridors of the Grijalva River system and this was not built in a rural area. Moreover, this centre, in addition to the Petén sites, did not exist in the far countryside, nor did they have communal landscape and rock-art shrines for use in collective rituals. One Late Postclassic Maya site, Isla Cilvituk, located in rural Campeche (Alexander Reference Alexander, Kepecs and Alexander2005), may have functioned as a defensible stopover along regional trade and travel routes. However, the site is rather large compared to Mensabak settlements and it may have been a secondary centre. Additionally, no evidence was found at Cilvituk for canoe ports and storage, nor collective ritual at temples or landscape shrines.

Conclusions: rural stopovers in cultural context

The identification of a small rural stopover for travellers and traders along an informal, secondary route at Mensabak, Chiapas, underscores the economic, social and religious components of long-distance overland caravans and road networks seen in comparative contexts. Insights from archaeological studies of countryside stopovers add to knowledge of the complexity of social interaction and settlement types in these material and cultural contexts besides the trading ports, colonies and major routes that have been studied across the world. The defining characteristics of small rural stopovers seen in Mesoamerica and Eurasia and in the Andes are their locations in the distant countryside along travel routes, general availability of food and water, buildings for resting and storage, protective constructions for safe havens, places for small-scale trade and social interaction, the presence of people of different ethnicities, and religious shrines in the landscape, often with rock art, for collective worship. In the case of Mensabak, traders and pilgrims arrived here and interacted with the populations of these small rural settlements, such as La Punta and Tzibana. No direct architectural evidence or human burials currently point to an Aztec or Chontal Maya trade diaspora colony at Mensabak, although contact and trade with these people are seen in the substantial amounts of green Pachuca obsidian blades from Central Mexico and the Matillas Fine Orange ceramics from Tabasco. Maya leaders and merchants, and probably Aztec pochteca traders, maintained safe access to this site and they may have influenced local political and economic organizations.

Mensabak was not a port and not just a location of pilgrimage shrines. The adjacent site of Toniná near Ocosingo, on the other hand, was a Postclassic Maya pilgrimage centre where people buried their dead and performed rituals in ancient Maya ruins. At this site and others in the Ocosingo valley, only small amounts of Pachuca green obsidian, Matillas Fine Orange ceramics and copper bells have been found (Becquelin & Baudez Reference Becquelin and Baudez1979). These items recovered in domestic contexts and in plazas at Mensabak point to the presence of traders and Aztec merchants travelling between the Gulf Coast and the Chiapas highlands, and not just pilgrims visiting temples. Furthermore, Mensabak is more likely a small rural trade route stopover (caravanserai) rather than a Mesoamerican gateway centre like Chalcatzingo in Morelos (Hirth Reference Hirth1978), the international trade town of Xicalanco (Gasco & Berdan Reference Gasco, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003), a major pilgrimage centre like Cozumel (Freidel & Sabloff Reference Freidel and Sabloff1984), or a coastal port of trade as seen at Potonchan (Chapman Reference Chapman, Polanyi, Arensberg and Pearson1957), because of its small settlement size, rural location, location along rural overland routes and comparatively small amounts of exotic trade goods compared to ports. Trade at Mensabak was limited to select local items, like the historically known tobacco, animal skins, cacao, ceramics, copper bells, and green obsidian, rather than the many different types and larger quantities of exotic goods known for larger, more populous trading ports (Clark Reference Clark2016; Gasco & Berdan Reference Gasco, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003; Hirth Reference Hirth1978). The larger towns closer to markets, main routes, and denser populations in the Gulf Coast and Chiapas highlands served as gateway centres and international trading centres on the formal overland trade routes.

Small rural stopover sites can be discovered and examined further with archaeology and ethnohistory, but investigators have to shift from centres and ports to often neglected rural areas, particularly in Mesoamerica. Historical documents (Feldman Reference Feldman1985; Lee & Navarrete Reference Lee and Navarrete1978; Long Towell & Attolini Lecón Reference Long Towell and Attolini Lecón2010) and aerial LiDAR mapping (Ensley et al. Reference Ensley, Hansen, Morales-Aguilar and Thompson2021) demonstrate that small rural sites, and possible stopovers, were common across time throughout this region. In surveys and excavations, we can recover evidence for rural stopovers on travel routes, such as small sites with buildings and walls for protection, items related to long-distance trade, evidence of trails and countryside settlements, public interaction and trading spaces and communal religious shrines. The public areas for exchange, central buildings for storage and sleeping and religious shrines integrated local populations socially with travellers and merchants. Landscape shrines for collective ritual of travellers seeking safety and economic success while on the road, particularly at rock-art sites, are important elements for rural stopovers as well. The ritual, trade and the exchange of information lead to social interaction and solidarity at these intriguing sites. While some rural sites may have served as pilgrimage shrines or gateway communities, the smaller ones can function as practical stopovers and places for exchange among travellers between centres, especially if they are located on trade or pilgrimage routes. These places could also have served in small trade fairs where travellers and merchants met at rural pilgrimage shrines on secondary travel routes to exchange their goods and participate in ritual at prescribed times (Feldman Reference Feldman1985, 19–20; Freidel & Sabloff Reference Freidel and Sabloff1984; Palka Reference Palka2014). Furthermore, the stopovers can eventually become settlements attracting people due to their social, economic, protective and ritual significance. The presence of these small countryside sites and the growth of settlements around them accentuate their importance in human history as being crucial for integrating different ethnic groups, regional economies and powerful polities as long as they, the trade routes, collective religious rituals and inter-connected centres are maintained.

Acknowledgements

Research at Mensabak was funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, National Science Foundation, the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia de México, the University of Illinois-Chicago, and Arizona State University.