Coeliac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disease where the ingestion of gluten drives the autoimmune process. The only treatment for this disease is a strict gluten-free (GF) diet. Consuming this diet requires a major lifestyle change as adherence is necessary to avoid long-term health complications (e.g. poor bone health, lymphoma)(Reference Snyder, Butzner and DeFelice1,Reference Green and Cellier2) . This also means a major behavioural shift in food selection, food literacy and food purchasing patterns(Reference Russo, Wolf and Leichter3–Reference Case6). While it is possible to consume a nutritious GF diet(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7), this is a major challenge for children/youth and their families. Recent evidence has shown that the GF diet is characterised by high levels of added sugar, saturated fat, low intakes of several micronutrients (e.g. folate, vitamin D) and low diet quality(Reference Mager, Liu and Marcon8–Reference Ting, Katz and Sutherland15). The lack of nutrient fortification in processed GF grains (e.g. folate) and suboptimal dairy intake are major contributors to low micronutrient intake in children/youth with CD(Reference Mager, Liu and Marcon8,Reference Jamieson, Weir and Gougeon16–Reference Pellegrini and Agostoni18) .

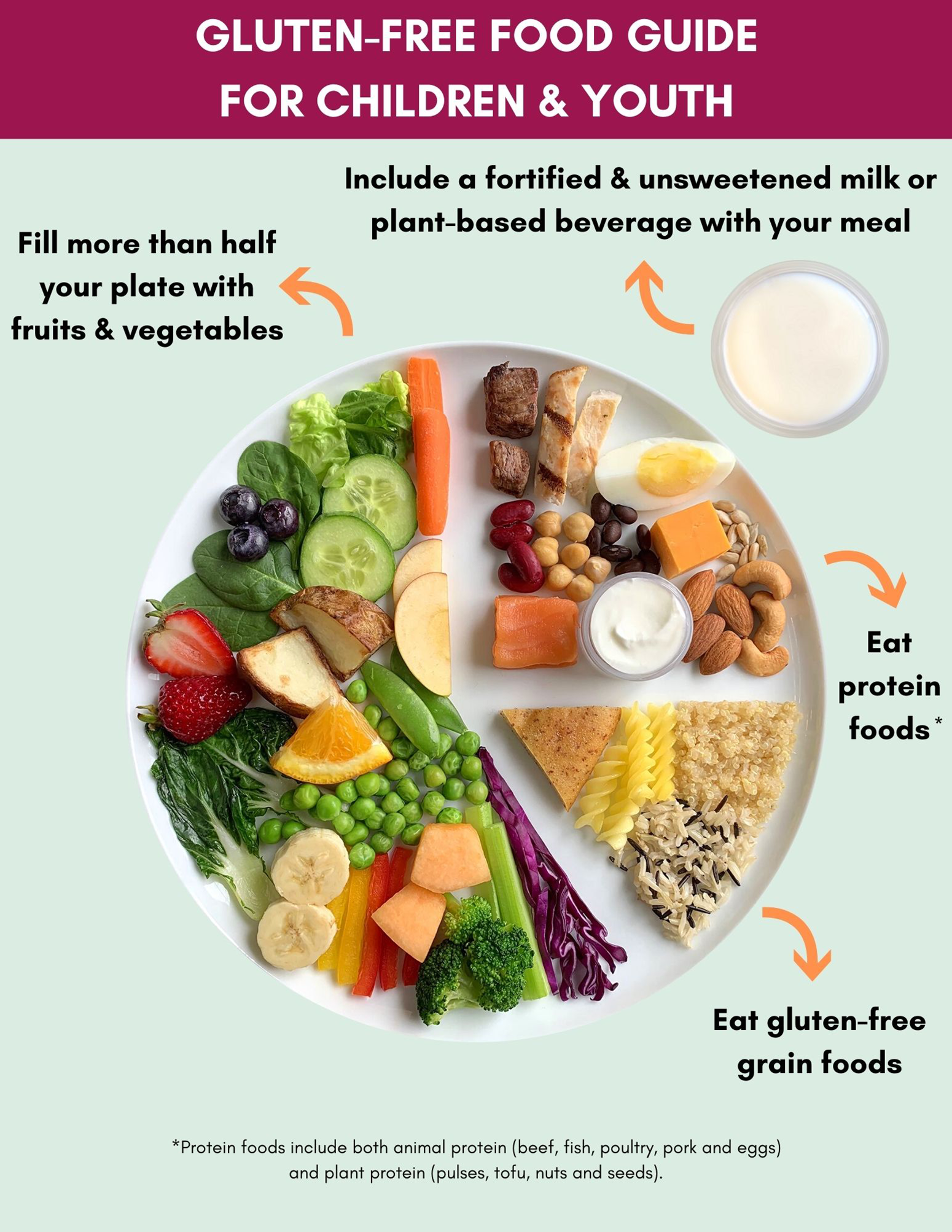

Food literacy education on the GF diet in newly diagnosed children/youth and their families is critical to manoeuvre the nutritional complexities of following a GF diet. However, access to dietitians with specialised knowledge in CD and the GF diet can be limited within the community(Reference Isaac, Wu and Mager19). The 2019 Canada’s Food Guide (CFG) provides Canadians with voluntary guidance regarding healthy eating behaviours for chronic disease prevention; however, these guidelines do not take into account the unique nutritional considerations of the GF diet(20,21) . To address this important gap, our team has reported on the methodological and nutritional considerations of a newly developed GF food guide for Canadian children and youth with CD (4–18 years)(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7). This report illustrates that a GF plate model which reflects > 50 % fruits and vegetables, 25 % protein and < 25 % GF grains is recommended to support children/youth in meeting their nutritional needs (Fig. 1)(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7). The key messages of the GF food guide focus on fruit and vegetable intake, limiting highly processed GF foods and emphasising key nutrients (e.g. vitamin D, folate, iron, calcium, fibre)(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7). In addition, messaging that encourages children/youth to enjoy their food is important to foster healthy eating habits. One major difference between the plate model of the GF food guide compared with the 2019 CFG is the recommendation to include fortified and unsweetened milk or a plant-based alternative to ensure that growing children/youth with CD meet their calcium and vitamin D needs(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7,20) .

Fig. 1. The gluten-free food guide for children and youth with coeliac disease. This guide is a two-page document. Illustrated above is the first page which includes the gluten-free plate model and the following four key messages: (1) fill more than half your plate with fruits and vegetables to meet your nutrient needs, (2) eat protein foods from plant and/or animal-based sources, (3) eat gluten-free grain foods, (4) include a vitamin D and calcium fortified and unsweetened milk or plant-based beverage with your meal. The second page of the gluten-free food guide (not shown) includes an additional six key messages: (5) choose foods that are rich sources of folate, iron and fibre, (6) eat less gluten-free processed foods to limit saturated fat, added sugar and sodium intake, (7) read food labels and ingredient lists for gluten and nutrition content, (8) cook at home more often, (9) drink water throughout the day, (10) enjoy gluten-free foods. All key messages were adapted based on the recommendations outlined in the 2019 Canada’s Dietary Guidelines(21).

Formative evaluations have previously been used to refine healthcare innovations before being widely distributed to end-stakeholders. This helps researchers make timely and appropriate changes to improve uptake(Reference Elwy, Wasan and Gillman22–Reference Stetler, Legro and Wallace24). We used this approach to ensure that the GF food guide and the supplementary educational materials translated into feasible and useable materials within multi-ethnic community and clinical-based settings across Canada. The study objective was to conduct an evaluation on the GF food guide for content, layout, feasibility and dissemination strategies from end-stakeholder users (children/youth, their parents/caregivers and health care professionals (HP)). We hypothesise that the GF food guide for children/youth with CD will contain evidence-based content that is feasible and usable with understandable nutritional information for children/youth, their families and HP.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study using a multi-method approach of virtual focus groups and Internet surveys to conduct post-guide formative evaluations. Stakeholders were consulted from across Canada to obtain their perception on the content and layout of the GF food guide for children and youth (4–18 years). This included a convenience sample of the coeliac community (e.g. children/youth with CD, parents/caregivers) and HP (e.g. dietitians, physicians and nurses). The detailed inclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1. Stakeholder inclusion criteria

CD, coeliac disease; GF, gluten-free.

* Exclusion criteria: non-Canadian resident; focus group: ≤ 7 years of age; survey: ≤ 14 years of age.

† Survey eligibility was expanded to include all adults ≥ 19 years of age with CD (even those without a child with CD) to ensure that all perspectives were ultimately considered.

Gluten-free food guide for children and youth

The GF food guide consists of a two-page visually appealing document that is accompanied by twenty-two educational handouts and four video resources (Fig. 1, online Supplementary Table S1). These materials provide education related to a variety of important topics (e.g. food preparation, food shopping and micronutrients). The first page of the food guide shows the GF plate model which illustrates the recommended distribution of food groups on the plate with four key messages (Fig. 1). The second page provides a total of six key messages targeted towards children/youth living with CD on the GF diet. These messages were based on the healthy eating recommendations for the Canadian population (≥ 2 years) outlined in the 2019 Canada’s Dietary Guidelines that were vetted and validated by Health Canada(21). The supplementary educational materials cover a variety of different nutrient and lifestyle topics (> 20 topics) to support the unique needs of children/youth with CD.

Participant recruitment

Focus group participants and Internet survey respondents were recruited using recruitment flyers and newsletters that were disseminated through a variety of electronic communication channels across Canada. These included health organisations (e.g. Alberta Health Service), provincial regulatory bodies (College of Dietitians of Alberta), professional organisations (Canadian Celiac Association, Canadian Association of Gastroenterology,) and/or community run social media pages.

Focus groups

Focus groups were conducted virtually between September 2020 to January 2021 using Zoom Video Communications Inc® V5.54(25). Each focus group was approximately 60-minutes in duration. Separate focus groups were conducted for youth alone (12–18 years), parents and their children (8–18 years), parents of children/youth (4–18 years) and for HP alone. Focus groups were facilitated by two trained and arm’s length moderators including a graduate student (S.C, RD) and a research assistant (C.L, BSc) who also made field notes during each focus group. An interview guide was used that consisted of twelve open-ended questions which were vetted by experts in the field. Questions were used to formally probe participants on their perception about the guide and the supplementary educational materials (e.g. handouts, videos) developed by our team.

Thematic analysis

Each focus group was audio recorded using two external voice recorders (Sony IC recorder ICD PX312®) with permission from all participants. Recordings were transcribed verbatim, de-identified and audited independently for accuracy by three trained reviewers. Data were collected until data saturation was achieved. Transcripts were independently reviewed by two co-investigators. Data were evaluated by an investigator (C.L) and coded to identify themes. This was cross verified by a second investigator (S.C) and then data were sorted into themes and sub-themes. Themes were sorted using Microsoft Excel. Both deductive and inductive coding approaches were applied to identify themes(Reference Braun and Clarke26). Data were reviewed until thematic saturation was achieved.

Internet surveys

Redcap® software was used to administer an anonymous Internet survey to the coeliac community and HP between November 2020 and February 2021(Reference Harris, Taylor and Thielke27,Reference Harris, Taylor and Minor28) . The thirty-one item survey contained open and close-ended questions related to the GF food guide for children/youth and the supplementary educational materials. Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00103128). Informed consent and/or assent was obtained from all focus group participants, and implied consent was obtained from all eligible Internet survey respondents.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Analysis Software (SAS; version 9.4 SAS Institute). χ 2 and Fisher’s exact statistical analyses were performed on demographic and close-ended survey questions. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·05.

Results

Stakeholder consultations

Demographic factors

The coeliac community (n 273) and HP (n 80) provided their perceptions on the GF food guide and the supplementary educational materials (Table 2, online Supplementary Fig. S1). No significant differences in geographic location were noted between focus group participants and survey respondents and/or between survey respondents whose responses were included in the analysis versus those excluded (P > 0·05).

Table 2. Demographic data

(Numbers and percentages)

CD, coeliac disease; IQR, interquartile range; y, years.

* A total of 19 focus groups were conducted: n 11 with health care professionals and n 8 with the coeliac community (n 2 with youth only, n 3 with parents and children, n 3 with parents only).

† 8–11 years.

‡ 12–18 years.

§ Western Canada: British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Northwest Territories, Yukon. Eastern Canada: Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut.

|| n 28 health care professionals and n 149 coeliac community members completed all survey responses; n 14 health care professionals and n 95 coeliac community members completed partial survey responses. Respondents were not required to answer all survey questions.

¶ ≥ 19 y: an adult with CD but who does not identify as a parent of a child/youth with CD; Parent (+): a parent with CD who has a child/youth with CD; Parent (−): a parent without CD who has a child/youth with CD.

** n 1 health care professional responded ‘prefer not to answer’ to the survey question.

Themes and sub-themes

Similar themes and sub-themes were identified from the focus group participants and survey respondents (Fig. 2, Table 3, online Supplementary Table S2). All stakeholders provided comprehensive evaluations and few differences were noted between the feedback received from children v. youth.

Fig. 2. Themes and sub-themes identified post stakeholder consultations. A total of eight themes and eighteen sub-themes were identified from the consultations conducted with virtual focus group participants and online survey respondents.

Table 3. Selected quotes from focus groups illustrating themes generated by stakeholders

C: child/youth; y: years old; P: parent; HP: health care professional.

Gluten-free food guide content

Focus group participants, including children/youth, supported the GF plate model and appreciated the variety of GF foods shown on the plate. Survey respondents also reported satisfaction with the food items (community members (94 %, n 211 out of 225) and HP (89 %, n 34 out of 38)). The fruits and vegetables were described by children/youth from the focus groups as colourful and encouraging to eat, but additional favorites were suggested (e.g. strawberries, melons). Red meat was a key item that HP and parents from across Canada considered important due to its iron content. Certain GF foods on the plate (e.g. quinoa, yogurt) were not easily identifiable by some focus group participants, but it was acknowledged that this was the same case for these individuals regarding the 2019 CFG plate model as well. HP believed that the inability to identify some foods on the plate could help spark positive conversation among children/youth and their parents related to food preferences and food literacy including nutritional composition.

A stronger emphasis to include more affordable food options on the plate such as frozen or canned varieties of fruits and vegetables was suggested. Root-based vegetables were also suggested, especially potatoes which were noted as staples in the North American diets of children(Reference Beals29). Feedback also advocated towards addressing seasonal availability and accessibility, particularly for families living in rural settings and/or in northern Canada.

Focus group participants, including children/youth supported fortified and unsweetened fluid milk or a plant-based alternative as the beverage of choice to increase their calcium and vitamin D intake. However, parents and HP also wanted additional clarification on why this piece differed compared with the 2019 CFG and more information on the recommended servings compared with water. HP also wanted to see more guidance on calcium, whereby initially, the message in the guide primarily targeted vitamin D.

Community (91 %, n 160 out of 175) and HP (82 %, n 28 out of 34) survey respondents agreed that the key messages outlined in the guide were understandable. Yet, they also desired more information on why these recommendations were made along with clearer language and examples of nutrient specific food items (e.g. folate) to help families put the recommendations into context. Focus group participants felt similarly but also believed that the supplementary educational materials would likely address some of these concerns.

Gluten-free food guide layout

Focus group participants appreciated that the GF plate model was visually comparable with the 2019 CFG. Yet, children/youth particularly liked that this guide only provided GF food options. Parents and HP thought the volume of food depicted on the plate was overwhelming for younger children, but younger children did not directly comment on this concern. Survey respondents shared this viewpoint and suggested to reduce the volume but keep the same variety to address this concern.

There was agreement on the design features of the guide with minor suggestions to improve spatial organisation, scaling and graphic elements. The feedback was similar for the supplementary educational materials. Focus group participants, including children/youth, described the guide as appealing, colourful and concise (i.e. two pages). Parents did not consistently notice that the proportion of fruits and vegetables on the plate was > 50 % and differed from the 2019 CFG. Children/youth more readily noticed this difference which some attributed it to being very familiar with the 2019 CFG. Parents felt that larger ‘spaces’ between the food groups and that strategically placing foods on the plate would make this more apparent.

Ethnicity

Children/youth and parents from the focus groups expressed that the plate model showed a good representation of cultures and food traditions. They felt that the food items (e.g. vegetables, rice, legumes) could easily be incorporated into a variety of traditional dishes. Additional considerations on cultural representation (e.g. South Asian) and food suggestions (e.g. roti, bok choy, melons) were equally provided to better represent the Canadian population.

Feasibility

Children/youth acknowledged that eating > 50 % of fruits and vegetables at meals and snacks would require more effort to prepare but could be achieved. Parents felt that more planning and preparation would be required and acknowledged that their children typically eat more GF grains due to preferences and convenience. Feasibility was not a theme frequently brought up by survey respondents.

Supplementary educational material content

Parents and HP felt that the educational materials would help meet the unique needs of children/youth with CD. Survey respondents (community members (96 %, n 161 out of 168), HP (97 % n 31 out of 32)) shared similar viewpoints. However, some additional topics were requested by children/youth, parents and HP. This included information related to social events, cross-contamination, GF grains and flours (e.g. listing different types, how to cook and/or bake with them). Younger children also wanted more information on GF recipes while youth wanted information on eating out safely while on the GF diet (e.g. fast foods, restaurants). It was also agreed upon that these materials should be available in different languages (e.g. French).

Useability

Focus group participants felt that the guide and the supplementary handouts would be useful to educate children/youth with CD. This was confirmed by survey respondents (community members (86 %, n 128 out of 149), HP (90 %, n 25 out of 28)). Video-based resources were not as popular (community members (77 % n 114 out of 149), HP (54 %, n 15 out of 28)). HP survey respondents were concerned about video length during clinic visits whereby parents felt that uptake would depend on the exact topic and the target audience of the videos (i.e. children/youth, parents and both). Still, most agreed that access to any of these resources would have been beneficial at time of diagnosis and that they will benefit future children/youth with CD. Survey respondents (70 %, n 123 out of 177) reported that both electronic and paper-based documents should be available to ensure equitable and convenient access to all demographics. This mixed response was shared by focus group participants.

Discussion

The intent of the GF food guide is to provide general nutrition guidelines for children/youth following the GF diet. The plate model is to illustrate what proportions of food should be consumed to ensure a healthy GF diet. Transitioning to a GF diet can be challenging for children/youth with CD since dietary restrictions can impact their psychosocial well-being and differences in the nutrient density of GF foods may adversely impact macronutrient and micronutrient intake(Reference Mager, Liu and Marcon8,Reference Rashid, Cranney and Zarkadas30) . Gluten restrictions can also result in stigmatisation and social withdrawal among the paediatric population especially at school(Reference Rashid, Cranney and Zarkadas30,Reference Olsson, Lyon and Hornell31) . Non-adherence by children/youth with CD can increase risk of health complications (e.g. poor bone health) as they struggle to restrict gluten-containing foods(Reference White, Bannerman and Gillett32). The GF food guide and the supplementary educational materials address the unique nutritional needs for children/youth on the GF diet(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7) (Fig. 1, online Supplementary Table S1). Therefore, these resources will help children/youth and their families of diverse cultures all around the world navigate the complexities of following the GF diet. Stakeholder consultations were conducted through a formative evaluation process to ensure that concepts related to content, layout, feasibility, usability and dissemination would be addressed within the GF guideline process. This evaluation was unique because it gathered feedback from children/youth with CD, their parents and HP to evaluate these concepts.

Overall, stakeholders positively perceived the GF food guide and the associated educational materials. Children/youth liked that the GF plate model mirrored the plate model from the 2019 CFG because it made them feel less ‘different’ than their non-CD peers. Since the stakeholders perceived children/youth to already face many dietary restrictions, they advocated to display certain GF foods on the plate that they perceived children/youth to really enjoy (e.g. cheese, potatoes). Cheese is an important component of the diet in North America, is a rich source of calcium and some hard cheese can be a good options for those with CD who experience lactose intolerance(Reference Ojetti, Nucera and Migneco33–Reference Chen, Wang and Tong36). While plant-based protein intake was emphasised within the GF food guide, parents and HP felt that animal-based sources (e.g. lean cuts of red meat) were also important in relation to the risk of suboptimal iron status at time of CD diagnosis(Reference Di Nardo, Villa and Conti11). While this may be perceived to add to saturated fat intake in children/youth, saturated fat intake in the diet simulations that included these food choices were well below current recommendations (< 10 % energy intake)(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7).

Stakeholders wanted additional clarifications as to why the GF food guide encourages fortified and unsweetened fluid milk or a plant-based alternative as the beverage of choice, while the 2019 CFG encourages water. In growing children/youth, calcium and vitamin D are key nutrients for bone health(Reference Munasinghe, Willows and Yuan37). Since this guide solely targets children/youth on the GF diet and they are at risk of suboptimal vitamin D intake, this can be a practical solution to increase intake(Reference Mager, Cyrkot and Lirette7,Reference Mager, Qiao and Turner13) . These sources also contain protein, riboflavin, vitamins A and B12 to contribute to nutritional adequacy in the diets of children/youth(34). For additional hydration, water is a healthy choice and is still encouraged to be consumed ad libitum throughout the day. Dietary supplementation for calcium and vitamin D is an alternative option, but inconsistent adherence has been reported(Reference Hoffmann, Alzaben and Enns38).

Knowledge translation

Dissemination strategies

The dissemination plan was made with an intent to increase awareness about the GF food guide and the supplementary educational materials. This was needed so that children/youth and their families know where to access reliable information since the burden of treatment falls heavily on them to strictly adhere to a GF diet. When Health Canada launched the 2019 CFG, multiple dissemination strategies were observed including a Canada-wide press conference with media coverage, a website re-launch, social media presence and webinars(20,Reference Woodruff, Coyne and Fulcher39,40) . The use of combined strategies, including one-way and mutually reinforcing strategies, has been shown to help create awareness and discussion(Reference Schipper, Bakker and De Wit41). Standalone paper or electronic lay resources can be another strategy, but they need to be easily accessible to facilitate awareness and unambiguous and clear to empower families to adopt them(Reference Schipper, Bakker and De Wit41). Collaborating with frontline HP is another strategy to help reinforce standalone resources to patients/clients during clinic visits, answer their questions and address any misinformation or confusion(Reference Schipper, Bakker and De Wit41). With support from HP, consistent information and trusted messaging can be better disseminated to Canadians(Reference Garza, Stover and Ohlhorst42). Endorsements made by well-known public figures (e.g. Registered Dietitian), nutrition champions (i.e. past focus group children/youth or parents) or trusted organisations such as provincial or territorial health authorities and/or the Canadian Celiac Association, including local chapters can also facilitate reach(Reference Schipper, Bakker and De Wit41). Recurring dissemination strategies have also been pursued by Health Canada with the release of monthly newsletters and routine social media posts. This strategy permits the sender to expand, reach and reminds the public that these evidence-based tools exist thus facilitating awareness and uptake(Reference Schipper, Bakker and De Wit41). Guide dissemination directly to schools can be another strategy to reach families and their children/youth at a critical period of learning and growth. About 20 % of surveyed Canadians reported receiving a copy of the CFG from their child’s school(Reference Slater and Mudryj43).

Implications to uptake

Stakeholder evaluations were proactively used to address potential factors that may inhibit or facilitate future guide uptake. A unique difference compared with the 2019 CFG is the greater proportion of fruits and vegetables shown on the plate. Historically, children/youth have not met their serving recommendations(Reference Garriguet44) due to factors such as preferences, sensory appeal and financial constraints(Reference Rasmussen, Krolner and Klepp45,Reference Chu, Farmer and Fung46) . Children/youth were key stakeholders to inform food selections and cited that the variety and colours were appealing and engaging. Plates of food that are colourful have been preferred by children, and visually appealing fruits and vegetables have notably promoted intake(Reference Zampollo, Kniffin and Wansink47,Reference Krolner, Rasmussen and Brug48) . The plate model also includes nutrient-rich examples of relatively affordable food options such as root-based vegetables (e.g. carrots, potatoes)(Reference Reed, Frazão and Itskowitz49). Frozen fruits and vegetables were also included due to increased accessibility, longer shelf-life and year-round availability(Reference Miller and Knudson50).

Conducting food literacy interventions will also be important to help support children/youth and their families to voluntarily use these resources and improve the feasibility of recommendations. Interventions related to food skills (e.g. learning how to cook GF grains), label reading, meal planning and overcoming picky eating can empower families to prepare meals at home according to the GF plate model and key messages. Developing knowledge and skill earlier in life can help foster positive eating habits into adulthood and make these recommendations more feasible on a routine basis(Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris51,Reference Vanderlee, Hobin and White52) . Other possible facilitators to guide adoption may stem from aesthetic qualities of materials which can influence perceived usability, satisfaction and uptake(Reference Talati, Pettigrew and Moore53,Reference Truman54) . Future interventions may be needed to address behaviour change or time barriers (e.g. full-time employment), which may prevent families from adopting and routinely following the guide.

In this study, strengths included the use of a multi-method approach with virtual consultations that allowed for pan-Canada feedback with cross-cultural input. This method helped obtain perceptions from across Canada where the accessibility and availability of GF foods can differ. Some limitations include the lack of information regarding socio-economic status of study participants and the smaller sample size of the children/youth who participated in focus groups. However, socio-economic status was addressed and highlighted by both parents and HP as an important factor that may influence food guide uptake and adherence to not only food guide recommendations but with the actual GF diet. This is likely due to the high costs associated with GF food(Reference Kulai and Rashid55). One highlighted factor by parents in particular was that the food guide should focus on less expensive food choices within the GF diet (e.g. root-based vegetables). Recruiting a larger sample size of children/youth would have conferred increase rigor to the study design. However, we had a large representation of parents with children in both the focus groups and Internet surveys. This is highly relevant since parents are often the main influencer of the dietary intakes of younger children(Reference Vereecken, Haerens and De Bourdeaudhuij56) and would be the main users of the guide itself. Additional recruitment of older children/youth would have conferred increased strength as they take more authority over their food choices(Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson57). The feedback included an evaluation of supplementary educational materials and the need for additional content. One important concept will be the inclusion of a bilingual GF food guide (English and French) and translation to other languages to reflect the needs of culturally diverse communities. This is important to ensure that all materials can be used internationally.

Conclusions

A GF food guide for children and youth addresses a major gap in the literature as there are currently no evidence-based nutrition guidelines that focus specifically on the GF diet. The evaluation of the GF food guide for content, layout, feasibility and dissemination strategies by end-stakeholders (children/youth with CD, their parents/caregivers and HP) provided practical and patient-focused feedback regarding the GF diet. This information is critical to ensure that guide uptake is successful in the community and clinical-based settings. Ongoing work will focus on guideline uptake in children/youth with CD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge Daria Antoszko, Aviva Sharma, Anushka Vadgama and Wendy Zhou for their assistance with this research study. The authors would also like to gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the children/youth, their parents and the health care professionals who participated in this research study.

This work was supported by the Canadian Celiac Association: Edmonton and Calgary Chapters; Alberta Health Services – Maternal Newborn Child and Youth Strategic Clinical Network; Alberta Health Services – Diabetes, Obesity and Nutrition Strategic Clinical Network; Vitamin Fund provided by the University of Alberta; Canadian Celiac Association JA Campbell award (2019, D.R.M); WCHRI Graduate Studentship by the support of the Stollery Children’s Hospital Foundation through the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute (2020, S.C); Sir Frederick Banting and Dr. Charles Best Canada Graduate Studentship – Master’s (CIHR CGSM) (2020, S.C); Walter H Johns Graduate Fellowship from the University of Alberta (2020, S.C); Alberta Graduate Studentship (2019, S.C) and the Alberta Diabetes Institute Graduate Studentship by donation from the G. Woodrow Wirtanen Studentship (2019, S.C). Funders had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this manuscript.

D. R. M.: Conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. S. C.: Conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition (scholarship funding), methodology, project administration, resources, software, visualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. C. L.: Conceptualisation, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, resources, software, visualisation, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. H. B.: Funding acquisition, project administration, writing – review and editing. J. D.: Visualisation, writing – review and editing. H. M.: Project administration, visualisation, writing – review and editing. C. B-H.: Project administration, writing – review and editing. R. N.: Project administration, visualisation, writing – review & editing. E. A.: project administration, writing – review and editing. M. M.: Conceptualisation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, visualisation, writing – review and editing. J. M. T.: Conceptualisation, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, visualisation, writing – review and editing.

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material/s referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521002774