While it is not a perfect example of a “love triangle,” managing and maintaining a constructive and professional triangular relationship between authors, reviewers, and editors constitutes the core of a successful academic journal and an effective peer-review system more generally. It is only when authors get the impression that the decisions and feedback they receive from editors and reviewers are justified and based on a genuine assessment of their work, will they be willing to contribute to the journal’s “reviewer common good” themselves. By the same token, as time is limited, if reviewers get the feeling that the time spent reviewing for a journal is appreciated and that their feedback contributes to the editors’ decision-making and helps authors to improve their manuscripts, will they also accept future reviewer requests and submit their reviews to the journal in a timely manner. Both are necessary for any journal to continue publishing peer-reviewed work at the highest standards.

In recent years, the continuous increase in the number of submissions has been a key challenge in maintaining balance in this triangular relationship. In 2018, the American Political Science Review (APSR) hit another record in submission numbers by receiving 1,227 new manuscripts, ultimately receiving 2.4% more submissions than in the year prior and 25% more submissions than in 2015, the year before our current team took over the editorship. To respond to this development, which other outlets also face, editors have two realistic strategies at their disposal.

First, they can increase the desk rejection rate. This strategy may, however, put strain on the triangular relationship as it is likely to upset authors who may get the impression that their work is not thoroughly evaluated. As a consequence, upset authors are less likely to accept review invitations from the respective journal. Second, editors can invite more reviewers. However, this may also have negative consequences for the triangular relationship, specifically for two similar and connected reasons. As the pool of potential reviewers does not grow at the same rate as submissions have in the past, it either requires a higher workload for reviewers or additional efforts on behalf of the editorial team to discover new reviewers. The former, in particular, may backfire and contribute to the often discussed “reviewer fatigue,” wherein reviewers feel that their (unpaid) time is too often absorbed by a journal. As a result, reviewers are more likely to either reject review invitations, prolong the review process by delaying the submission of a review, and/or submit reviews with little feedback. Any of these scenarios add additional time to the already slow review process because editorial teams need to search for reviewers with expertise in the topic of the manuscript who also submit their reviews with adequate feedback on time.

During our editorship, we have tried to engage in both strategies, increasing the number of desk rejections as well as identifying and inviting new reviewers to maintain the rate of review acceptances, the duration, and the quality of submitted reviews in spite of the increasing number of submissions. Because we have already discussed the consequences of higher desk rejection rates before, in this issue’s Notes from the Editors, we want to take a closer look at how the increasing manuscript submission rate has affected the peer-review process. Specifically, we are going to focus on the trajectory of the annual number of invitations to review sent out by our journal, how often invited reviewers accept to review for the APSR, and how many reviews are ultimately submitted. To capture potential signs of reviewer fatigue, we are additionally going to report on the average review duration and report length. In general, this short investigation indicates that our efforts seem to be paying off. Although we reduced the number of invitations, the average acceptance share to review has increased. Moreover, both the average review duration and review length have remained at constant levels over time.

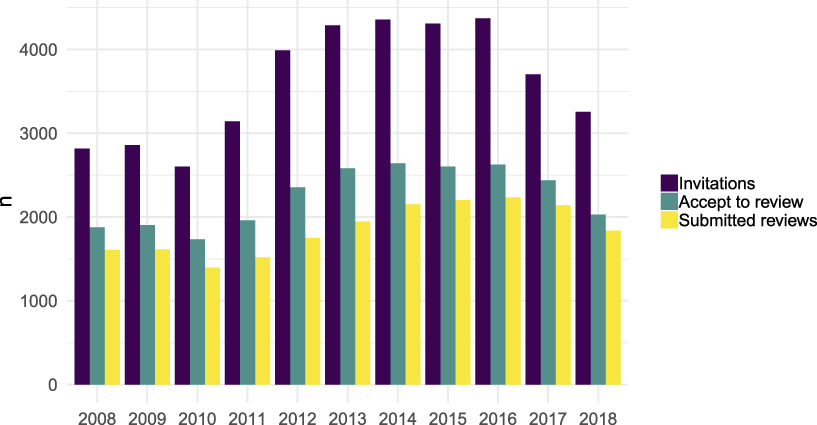

Figure 1 shows the development of annual numbers of invitations to review, acceptances to review, and submitted reviews in absolute terms. Regarding invitations, the graph clearly shows that our current editorial team successfully reduced the number of invitations to review sent out from 4,309 invitations in 2015 to 3,254 invitations in 2018, a decrease of 24%. This way, we have been able to keep the average annual number of invitations to review per invited scholars at a relatively stable level. Although the number of submissions rose by more than 25% since 2015, the annual invitation share per reviewer increased by less than 1% during this time with an average of 1.2 invitations in 2018. The effort to maintain the reviewers' workload at similar levels is not only due to our higher desk rejection rate of approximately 40% in 2018, but additionally, our editorial team's hard work at deepening the reviewer pool. Accordingly, the share of newly registered reviewers among invited reviewers has continued to increase. In 2018, the share of newly registered reviewers constituted 14% of invited reviewers, which is only slightly higher than the ten-year average of 13%. Together with our internal policy to only invite a reviewer three months after his or her last submitted review, it kept the invitation rate at a reasonable level.

FIGURE 1. Absolute Annual Number of Invitations to Review, Acceptances to Review, and Submitted Reviews

Second, the development of the number of accepted invitations to review seems to follow the number of invitations at a relatively stable rate, as also shown in Figure 1. In fact, the average share of invited reviewers who accepted an invitation has remained rather stable over the years. Relative to the number of invites, the average acceptance share was 66% in 2008, 60% in 2015, and 62% in 2018. Acceptances to review are an important indicator of how scholars perceive a journal and its standing in their field of expertise. Although we occasionally experience scholars rejecting an invitation to review for the APSR because they feel that editors and reviewers are prejudiced against their subfield or methodological approach, the most common mentioned reason is “too many reviews on the desk” or “too many other professional obligations to review.” Therefore, the moderate increase in relative invitation acceptance rates that we have observed since 2015 suggests that the efforts to avoid “reviewer fatigue” has paid off (at least on average).

Third, we turn to the annual number of actual submitted reviews, which reflects the amount of work that reviewers provide to the “common good” for the APSR. In absolute numbers, we observe again a close relationship between the number of acceptances to review and the number of sent-out invitations (see Figure 1). However, the relative share of submitted reviews in comparison to the number of accepted invitations has continued to increase since 2015. In fact, our predecessors had already increased the actual review submission rate from 75% in 2012 to 85% in 2015. Last year, the submission rate among reviewers who accepted to review reached almost 91%, another increase of 7% compared to 2015. Furthermore, the number of reviews that the average reviewer submitted in a year has remained stable over time. Even though there are reviewers in our database who have submitted up to five reviews per year, the average number was 1.1 reviews in 2018. These figures suggest that the de facto workload of reviewers in the APSR stayed at similar levels despite the substantial increase in submissions.

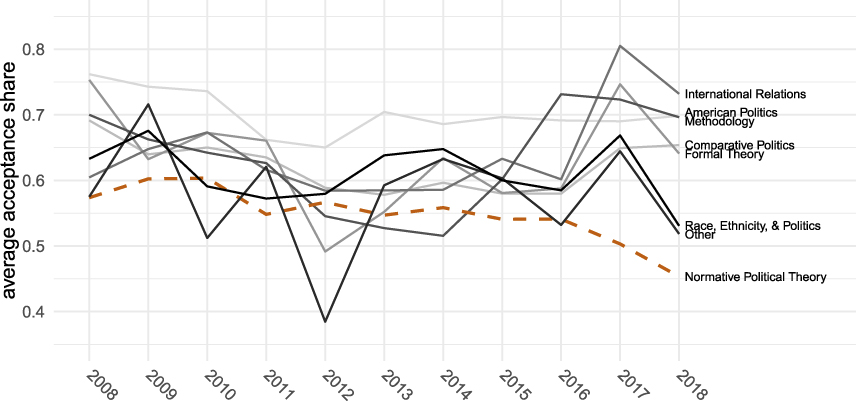

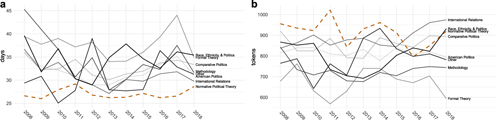

However, we also want to report that not all subfields seem to be developing in a similar manner. In this regard, Figure 2 shows the annual acceptance rate to review by subfields. Although the acceptance rate has remained relatively constant or even increased in most subfields, we observe a continuous decline in the acceptance share to review in the subfield of Normative Political Theory. Admittedly, we can only speculate about the underlying reasons. Naturally, we cannot exclude that some declines may be associated with perceptions of the APSR, which is understandable, but all editorial teams have been following the same pluralist publication strategy and working to represent all subfields of our discipline. We tried to go further by implementing a bilateral decision-making process between associate editors and the lead editor to reduce field-specific bias. Such a perception would stand in contrast to the publication likelihood—measured by the number of published articles in relation to the number of submissions, which is highest for Normative Political Theory (7.3% compared to 5.2% in other fields). In other words, the overall acceptance rate (21.7%) is higher than the overall submission rate (16.6%) in Normative Political Theory.

FIGURE 2. Relative Annual Acceptance Share to Review by Subfield

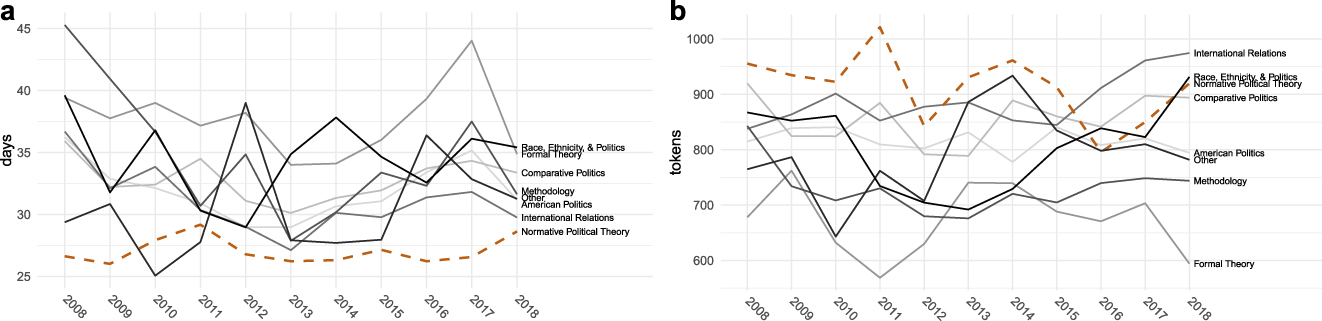

For each subfield, review duration and textual length serve as indicators of how much time and effort reviewers spend on giving feedback to authors and editors. Accordingly, it is important to note that both indicators have been astonishingly stable across years on average, thus, not revealing any signs of change in reviewer fatigue (see Figure 3). The ten-year average review duration is 32 days and a typical report has a length of about 840 words. On close inspection of subfields, we observe some small variation over time. In most subfields, the average review duration has decreased in recent years. Yet, Normative Political Theory constitutes again an exception. In spite of a recent small increase, the duration time is still the fastest among all subfields. Similarly, the reviewers’ feedback in this subfield continue to be one of the largest in terms of text length. Taken together, it seems that the lower acceptance rate can hardly be attributed to reviewer fatigue. In addition to the highest publication likelihood, review duration and length indicate that the peer-review process in Normative Political Theory is among the most effective ones.

FIGURE 3. Annual Review Duration (Days with Reviewer) and Text Length of Reviewers’ Comments to the Author (Number of Tokens)

All things considered, the presented numbers raise our confidence that despite the increasing submission rate felt across journals these days, the peer-review process has not been affected in a negative manner. However, we believe that the trend will remain one of the most important challenges editors face in keeping reviewer fatigue low for the years to come. As promised, we will continue analyzing and evaluating our data to provide authors, reviewers, and ourselves information about the peer-review process. We hope that this transparency maintains the constructive and professional triangular relationship between authors, reviewers, and editors that continues to motivate authors and reviewers to further contribute to the journals’ “reviewer common good,” which is essential for attracting and publishing excellent manuscripts from all subfields in political science.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.