Exile is an emotionally devastating experience, that’s well recognized. What not everyone grasps is that it’s also a politically transformative one.

Francisco Toro, “My Name is Francisco, and I Am a Toxic Exile,” Caracas ChroniclesExile—the banishment of dissidents from their home countryFootnote 1—is among the most common forms of repression targeting political opponents. Used by regimes to stifle opposition, its goal is to limit the influence of activists by splintering their networks and reducing their domestic influence (Esberg Reference Esberg2021). However, exiles typically continue their activism overseas. Activists from across the globe have used a variety of strategies to shape foreign policies and alter outcomes in their home countries.Footnote 2 The rise of digital media technologies has afforded exiled dissidents new platforms to disseminate messages, enabling them to amass large online followings and to produce content in multiple languages targeting diverse audiences (Kendzior Reference Kendzior2012; Michaelsen Reference Michaelsen2018). Although exile is a tried and true strategy for authoritarian and hybrid regimes seeking to stifle domestic opposition, we know relatively little about its effects, especially since the advent of social media (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2009).

In this article, we ask how exile affects elite online dissent. By forcing opponents from the country, exile internationalizes elites’ networks, strengthening their relationships with foreign audiences and opening new opportunities for international activism (Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007; Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016; Koinova Reference Koinova2021). It also removes them from day-to-day life in their home countries, making them less vulnerable to repression but also less directly connected to their domestic constituencies (Henry and Plantan Reference Henry and Plantan2022; McKeever Reference McKeever2020). Because of this, we argue that exile should fundamentally change activists’ strategies, including the types of policies and issues that they discuss publicly.

More specifically, we expect exile to change the content of activists’ dissent in three central ways. First, we expect exile to increase activists’ support for foreign-led policy solutions. Going abroad means that exiles are socialized into new communities and have very different methods of activism available to them. For example, exiles may be particularly well placed to lobby their host-country governments, but they are less capable than in-country activists of participating in domestic political processes (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2011; Reference Brinkerhoff2016; Henry and Plantan Reference Henry and Plantan2022; Koinova Reference Koinova2021). As exiles’ networks become more international, it follows that the types of policies that they discuss and advocate for publicly should change to highlight and take advantage of the tools that are most readily available to them.

Second, we expect activists to focus less on local grievances. With more international networks, exiles have incentives to focus on topics that resonate with a broad audience. Moreover, with less connection to on-the-ground events at home, exiles may have less knowledge of or involvement in matters of primarily domestic interest (McKeever Reference McKeever2020). As a result, we expect exiles’ rhetoric to shift away from local issues. Finally, we theorize that harsh criticisms of the home-country government should increase following exile. Bold, national-level critiques should resonate with a broader and more international audience. Activists may also be less likely to self-censor due to reduced fears of repression abroad, particularly where home-country regimes have low state capacity for transnational repression (Shen and Truex Reference Shen and Truex2021).

We test this theory in the case of Venezuela, where many opponents of Nicolás Maduro have gone into exile. To do this, we developed a dataset of online opposition speech. Drawing on lists of politicians and other opposition activists, we ascertained their exile status and collected their Twitter handles. We then gathered the full tweet history for the 357 activists in our sample dating back to January 2013, of whom 94 were exiled, totaling more than 5 million social media posts. Because Venezuela has one of the highest rates of Twitter penetration in the world (Silver et al. Reference Silver, Smith, Johnson, Taylor, Jiang, Anderson and Rainie2019) and the platform is widely used to discuss politics (Morales Reference Morales2020; Morselli, Passini, and McGarty Reference Morselli, Passini and McGarty2021; Munger et al. Reference Munger, Bonneau, Nagler and Tucker2019; Waisbord and Amado Reference Waisbord and Amado2017), Twitter data enable us to develop temporally granular measures of how exiled and nonexiled activists express dissent online.

Using text analysis and a two-way fixed effects design, we demonstrate that Venezuelan activists’ discourse changes after exile. After leaving the country, opposition figures become more likely to discuss and support popular foreign-led solutions to Venezuela’s political and economic crisis including diplomacy, foreign intervention, and sanctions. In contrast, activists in exile are somewhat less likely to discuss local grievances, like food shortages and blackouts, as well as local protests. Exile is also associated with harsher antiregime criticisms such as accusations of narco-trafficking, fascism, Cuban or Russian invasion, and extrajudicial repression.

Exploring the mechanisms by which exile might influence online dissent, our analysis suggests that after leaving Venezuela activists’ online networks become more international and focused on foreign actors. We demonstrate that discussions of foreign entities increase after exile, the percentage of tweets directed at international actors increases, and tweets in English become more common. We also show that references to the new host country particularly increase, providing further evidence that this internationalization is largely the result of new overseas networks.

By empirically demonstrating how exile influences activists’ online discourse, this work builds on a growing body of research examining the relationship between repression and dissent in the digital age (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013; Pan and Siegel Reference Pan and Siegel2020; Roberts Reference Roberts2018; Woolley and Howard Reference Woolley and Howard2018). Our focus on elite opposition figures also provides a novel contribution to the literature on diaspora activism abroad (Adamson Reference Adamson and Checkel2013; Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007; Girard and Grenier Reference Girard and Grenier2008; Koinova Reference Koinova2011; Reference Koinova2014; Koinova and Karabegović Reference Koinova and Karabegović2019; Moss Reference Moss2021).

More broadly, our findings offer new evidence of the political consequences of exile—one of the most ubiquitous but least studied forms of repression. Research on the individual-level consequences of dissent typically focuses on the effects of violent repression, like imprisonment or killings (Bautista Reference Bautista2015; García-Ponce and Pasquale Reference García-Ponce and Pasquale2015; Young Reference Young2019; Reference Young2020). Although exile is similarly used to undermine opposition, exiled communities are often actively engaged in agenda setting overseas (Danitz and Strobel Reference Danitz and Strobel1999; Girard and Grenier Reference Girard and Grenier2008). Our research shows how exile changes not only the geography of opposition movements but also the content of activists’ public dissent, in line with literature on how migration can shape political beliefs and tactics (Batista, Seither, and Vicente Reference Batista, Seither and Vicente2019; Careja and Emmenegger Reference Careja and Emmenegger2012; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow Reference Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow2009).

The Effect of Exile on Political Discourse

The goal of exile under repressive regimes is to fragment the opposition, scattering activists across countries to reduce the effectiveness of antiregime mobilization (Esberg Reference Esberg2021; Wright and Oñate Zuñiga Reference Wright and Zuñiga2007). By casting opponents out of the country, traditional opposition networks are broken and exiles no longer have direct access to the country’s citizens and institutions. Research on the individual-level effects of repression has found that proximity to violence often dampens political participation, which may make dissent less likely (Bautista Reference Bautista2015; García-Ponce and Pasquale Reference García-Ponce and Pasquale2015; Rozenas and Zhukov Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2013; Young Reference Young2020). This contributes to a broader literature on the dynamic relationship between repression and dissent (Carey Reference Carey2006; Reference Carey2009; Christensen Reference Christensen2018; Davenport and Moore Reference Davenport and Moore2012; Siegel Reference Siegel2011; Truex Reference Truex2018). However, much of this work focuses on overtly violent repression like imprisonment and killings.

Exile is markedly different from many other forms of repression in that exiles can continue their activism abroad. Literature on diaspora politics more broadly shows how activists from diverse home countries including Albania, Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, China, Chile, Cuba, Democratic Republic of Congo, Kosovo, Palestine, Libya, Russia, South Africa, Syria, Tibet, and Yemen have used brokerage, framing, ethnic outbidding, lobbying, coalition building, and the diffusion of ideas to shape foreign policies and alter outcomes in their home countries (Adamson Reference Adamson and Checkel2013; Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007; Girard and Grenier Reference Girard and Grenier2008; Koinova Reference Koinova2011; Reference Koinova2014; Koinova and Karabegović Reference Koinova and Karabegović2019; Moss Reference Moss2021; Shain Reference Shain1988; Reference Shain1994; Reference Shain2002). Indeed Shain (Reference Shain1999) described political exiles as “some of the most prominent harbingers of regime change in the world.” Social media has also transformed the tools available to exiles, giving opposition figures a platform to communicate publicly with other activists, international audiences, domestic citizens, and the regime itself (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016; Kendzior Reference Kendzior2012; Michaelsen Reference Michaelsen2018).

We expect that exiles’ behavior abroad will be shaped by their changing political opportunities and constraints in their new host countries (Koinova Reference Koinova2014; Wayland Reference Wayland2004). We draw on the literature on transnational social movements, though we focus in on an important subset of the broader diaspora and “diaspora entrepreneurs”: elite exiles who began their political work in the home country, under a repressive regime, and fled due to fear of harm related to their activism (Moss Reference Moss2021). We expect opposition elites, including those in exile, to be strategic actors who will adjust their activism to best achieve their goals. Given the widespread use of exile to suppress opposition, understanding how it changes the content of dissent is particularly important. We argue that exile changes dissidents’ political opportunity structures by internationalizing their networks and creating distance from the repressive regime.

First, moving abroad enables exiles to develop new relationships and audiences both among the broader diaspora and with foreign governments, civil society actors, and journalists (Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007; Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016). This “institutional acculturation” offers dissidents new opportunities for influence, or vertical voice (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2011; Henry and Plantan Reference Henry and Plantan2022; Hirschman Reference Hirschman1978). With access to new international audiences and the ability to lobby their host-country governments, exiles acquire a new toolkit for opposition. And as political actors, exiles should be strategically responsive to these opportunities. It follows that after moving abroad, activists should shift both their modes of activism and the content of their dissent to match their new circumstances.

At the same time, exiles’ links to the home community may weaken, particularly under conditions of harsh repression and censorship. As McKeever (Reference McKeever2020, 11) describes, “from their sanctuary, activists find they retain limited access to the closed political opportunity structure of their sending country but are offered a range of opportunities by their new host country.” Exiles are not able to engage in the forms of dissent that they may have done domestically, such as organizing marches against the regime or participating in formal political processes. Particularly without the ability to visit in person, their connections to local politics and constituencies may weaken, making them less engaged with on-the-ground events—even with digital technologies available (Henry and Plantan Reference Henry and Plantan2022; Hussain and Howard Reference Hussain and Howard2013; Karimzad and Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018; Kuran Reference Kuran1991; Pierskalla Reference Pierskalla2010). By leaving the country, their relative advantage in activism shifts to serving as “bridge figures” (Zuckerman Reference Zuckerman2013) between the host and home country, broadcasting messages to an international audience and brokering between previously unconnected actors and entities inside and outside of the home country (Andén-Papadopoulos and Pantti Reference Andén-Papadopoulos and Pantti2013; Koinova Reference Koinova2021; Moss Reference Moss2021; Shain Reference Shain1999).

Finally, going abroad reduces activists’ fear of repression and reprisals from their home-country governments. Although moving abroad does not free opposition figures from threats to their own safety or livelihoods—or those of their family members—they face fewer risks abroad than they do at home. Though transnational repression is on the rise globally and has been shown to have chilling effects on diaspora activism in diverse contexts (Adamson Reference Adamson2020; Adamson and Tsourapas Reference Adamson and Tsourapas2020; Dalmasso et al. Reference Dalmasso, Del Sordi, Glasius, Hirt, Michaelsen, Mohammad and Moss2018; Moss Reference Moss2021; Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2021), exiles should nevertheless be less vulnerable than at home. This should be especially true for dissidents from host states with low state capacity for transnational repression. Well-known exiled elites who began their activism under repressive governments may also be less vulnerable to the dampening effects of repression.

We focus on the online behavior of activists. Political actors are increasingly taking to Twitter to communicate policy platforms and criticize regimes that otherwise may limit freedom of speech (Pan and Siegel Reference Pan and Siegel2020). Unlike statements through organizations or to the press, communication on social media is direct and frequent, giving us a rich source of fine-grained data that reflects activists’ priorities, policy positions, and communication strategies. Although social media data do not necessarily allow us to assess whether true or sincere attitudes toward the regime change with exile, we can estimate how the content of activists’ strategic public discourse shifts. This, in turn, can tell us about how dissent changes with leaving the country, differentiating the approaches of activists forced out and those who remain.

We expect to see three central changes to activists’ online discourse after exile. First, exiles should increasingly promote and discuss foreign-led solutions to problems in the home country in response to the new networks and new opportunities afforded them (Koinova Reference Koinova2021). The exact nature of these solutions should reflect the foreign policy goals, ideology, and values of the host-country government, as well as the ideology of the exiles themselves (Shain Reference Shain1999). For example, Cuban exiles’ calls for harsh sanctions have dovetailed with the US government’s historically antileftist policies in Latin America (Falke Reference Falke2000). Similarly, Iraqi exiles’ calls to remove Saddam Hussein from power in the early 2000s aligned with hawkish US foreign policy goals dating back to the first Gulf War (Vanderbush Reference Vanderbush2009). Other diaspora communities have sought much more limited goals: Belarusian activists have used their position as pro-democracy advocates abroad to draw attention to repression at home and to lobby European governments to expand sanctions and cut ties with state-owned companies (Rudnik Reference Rudnik2021).

Second, exiles should focus less on local domestic grievances and activism, both in response to their new position as brokers between the host and home country and because their knowledge of certain aspects of local politics may be less relevant (McKeever Reference McKeever2020; Yeh Reference Yeh2007). Although we expect this to be true even as online tools facilitate transnational connections (Karimzad and Catedral Reference Karimzad and Catedral2018), the extent may vary based on exiles’ perceived likelihood of return as well as the degree of censorship in their home country. For example, China heavily censors discussions of collective action but allows for the expression of grievances more generally (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013). If discussions of local collective action are censored at home, we might observe an increase in such discussions as activists have the opportunity to comment on such issues for the first time. Alternatively, exiles from countries with strong censorship structures like China may experience even greater levels of disconnection with their home-country networks (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013).

Third, activists may phrase their criticisms in harsher terms, both strategically—to appeal to their growing international networks—and due to reduced self-censorship. We expect these effects to be moderated by state capacity for transnational repression, as fears of being targeted abroad may reduce exiles’ willingness to speak out (Adamson Reference Adamson2020; Adamson and Tsourapas Reference Adamson and Tsourapas2020; Dalmasso et al. Reference Dalmasso, Del Sordi, Glasius, Hirt, Michaelsen, Mohammad and Moss2018; Moss Reference Moss2021; Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2021). Such fear may moderate the effects we find, though concerns about international reach should be less intense for elite exiles, who are already vulnerable due to their history of open dissent in the home country.

Although the specific ways in which the content of dissent changes may vary by home- and host-country context, we expect our broad theory to hold for exiles coming from repressive regimes and seeking structural change in the home country. In these contexts, the goal of opposition activism both internally and internationally is national-level political reform through methods like regime change and negotiated settlement. In such cases foreign pressure may be particularly influential, local grievances may be of less direct salience to the political conflict, and there is a clear subject of criticism. Such exiles differ substantially from refugees fleeing generalized conflict, where first-order goals may revolve around reducing violence. They should also differ from exiles from ethnic groups and separatist regions, who typically seek more limited territorial and administrative goals revolving around self-determination. Nevertheless, our theoretical expectations apply to a variety of authoritarian and hybrid regimes that use repression to suppress opposition.

The Case of Venezuela

We test this theory in the case of Venezuela, where the increasingly authoritarian president Nicolás Maduro has often pushed opposition out of the country as a tool of control. Maduro first took power upon the death of his predecessor, Hugo Chávez, in March 2013. Since then, he has taken a number of measures to ensure greater control over the electoral system in an attempt to further disempower the opposition. Among others, these include barring prominent members of the opposition from running for office; vote buying, including by strategically doling out food aid and medical care; and packing the national electoral board and court system with loyalists (Casey Reference Casey2019; Faiola Reference Faiola2018; International Crisis Group 2020; Mainwaring and Pérez Liñán Reference Mainwaring and Liñán2015; Rodrigues de Caires and Sánchez Azuaje Reference de Caires, Carlos and Sánchez Azuaje2018). In response to electoral irregularities in the May 2018 elections, Juan Guaidó—a member of the National Assembly and a central figure of the opposition—declared himself acting president. The United States quickly recognized him, and dozens of other countries followed (though many, including the European Union, have since downgraded his status). Massive protests, as well as an abortive military uprising, occurred in the months after.

Simultaneously, Venezuela has suffered one of the most severe economic crises in decades. Inflation and the national debt exploded; poverty, fuel shortages, and hunger began to rise. Though initially buoyed by the price of oil, plunging prices reduced the government’s ability to spend on social programs to keep the political base intact (Davies Reference Davies2016).Footnote 3 One in three Venezuelans is food insecure (World Food Program 2020), and estimates suggest an 85% shortage in medicine, leading to a resurgence of treatable diseases (Agencia EFE 2017; Faiola and Krygier Reference Faiola and Krygier2018). Four in 10 households experience daily electricity outages (The Guardian 2020).

In this period of political and economic crisis, repressive actions against political opponents have intensified. The security services regularly respond to peaceful protests with beatings, tear gas, and close-range rubber bullets. Political opponents are imprisoned or barred from running for political office. Estimates suggest thousands of Venezuelans are now killed per year in extrajudicial murders (UNCHR 2019). For example, under the pretext of addressing terrorism, “Operation Peoples’ Liberation” led to more than 500 murders by the security services, as well as evictions, home raids, and detentions (Human Rights Watch 2019).

Online Political Discourse in Venezuela

Venezuela has a high rate of social media penetration, with 69% of adults using at least one social media app (Silver et al. Reference Silver, Smith, Johnson, Taylor, Jiang, Anderson and Rainie2019). As of 2019, 21% of Venezuelans use Twitter, compared with 22% of US citizens as a point of reference. Twitter has long been a popular platform for discussing politics in Venezuela. Indeed, Chávez was considered the second most influential leader in the world on Twitter (Morales et al. Reference Morales, Borondo, Losada and Benito2015). Twitter has also been heavily used by opposition activists and politicians in Venezuela, as in other parts of Latin America (Calvo Reference Calvo2015; Lupu, Ramírez Bustamante, and Zechmeister Reference Lupu, Ramírez Bustamante and Zechmeister2020; Morales Reference Morales2020; Morselli, Passini, and McGarty Reference Morselli, Passini and McGarty2021; Munger et al. Reference Munger, Bonneau, Nagler and Tucker2019; Waisbord and Amado Reference Waisbord and Amado2017). Government control over the media has increased under Maduro, with most news sources being state-run and even independent outlets heavily restricted (Nugent Reference Nugent2019). One blogger wrote in 2014, “No longer will we just settle on trusting that Globovisión will carry whatever little things we do. We will now have to explore the use of other outlets—Twitter, Capriles.tv, Facebook” (Friedman Reference Friedman2019).

As a result, Twitter plays an important role in the political media landscape in Venezuela more broadly. As one political figure in exile notes, “Twitter phenomena … try to condition, often with success, local politics” (International Crisis Group 2021, 16). Media produced abroad tends to get picked up in the local press and discourse, precisely because of limits on free speech domestically: “Exiles like those in Miami have a great deal of influence because of media capacity” (International Crisis Group 2021, 16). A 2014 survey found that 74% of Venezuelans learned about politicians’ political beliefs on Twitter, the most of any country polled (Friedman Reference Friedman2019).

Exile and Online Discourse in Venezuela

Maduro’s opponents are frequently forced into exile.Footnote 4 Although we lack statistics on repression in the country, nearly four million Venezuelans, about 13% of the population, have left since 1999 (UNHCR 2019). This exodus is largely due to the economic and humanitarian crisis, but many activists were also pushed out of the country (WLRN 2017). Political exiles in Venezuela often remain active in politics in their host country; for example, the Organization of the Venezuelan Politically Persecuted in Exile frequently advocates for aggressive US policies targeting Maduro.Footnote 5

Exiles themselves view the experience of leaving Venezuela as fundamentally altering how they approach the regime. One formerly exiled activist puts it in the following way: “It’s like cream and milk. When cream forms, it doesn’t look different from milk, but it’s not milk, you know? The same happens with the radicalization of the diaspora. [After exile] you’re the cream, not the milk within Venezuela.”Footnote 6 As Toro (Reference Toro2020) describes, “the day politics forces you out of your home, a wedge is driven between you and the country you leave behind.”

The theory presented above outlines the general patterns we expect to see when exiles leave a repressive regime, conditional on our scope conditions. However, we expect the specific ways these relationships evolve will vary, based on factors like the feasibility of different policy options and the threat of repression both at home and abroad (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016; Koinova Reference Koinova2021). We adapt our theory to identify three testable hypotheses for the case of Venezuela.

Our theory first predicts that exile should be associated with an increased discussion of foreign-led solutions to the Venezuelan crisis. Given that we expect exiles to advocate for policies that may appeal to their host country governments and are widely viewed as possible, we focus on the three most common proposed policy solutions in this period: military intervention, sanctions, and diplomacy. Although it has not been pursued, hardline opponents and international officials regularly discuss humanitarian or military intervention in Venezuela. Guaidó himself has said on international military action, “If it’s necessary, maybe we will approve it” (Faiola Reference Faiola2019). Others have proposed forceful humanitarian intervention to deliver aid (UN 2019). Since 2014 a number of countries—including the United States, Canada, and Mexico—have placed sanctions against individuals and companies associated with Maduro, targeting sectors from mining to food (Congressional Research Service 2020). Diplomacy by international actors has also been a popular solution to ease the political crisis in Venezuela in recognition of the country’s importance to broader geopolitics. To that end, Norway facilitated a series of talks that made some headway toward an easing of conflict (International Crisis Group 2022).

Second, our theory suggests that exile will be associated with less discussion of local grievances or mobilization efforts. For Venezuela, which is in the midst of multiple humanitarian and economic crises, we expect this to be most visible in discussions of devastating internal grievances related to issues like electricity blackouts, water and food shortages, and the struggling medical system. Despite the severity of this crisis, we expect that discussions of these shortages—particularly those describing local circumstances—will decrease: exiles are no longer affected by such shortages, they may lack details on when or where they are occurring, and such criticisms may be less relevant to international audiences. With respect to collective action events, Eubank and Kronick (Reference Eubank and Kronick2021) have shown that domestic networks in Venezuela are a major determinant of protest mobilization. Although there have been a number of very significant national protest movements, collective action events also take place at a smaller scale. One estimate suggests there have been as many as 50,000 protests in Venezuela since Maduro’s election (El Tiempo Reference Tiempo2019). Although we expect exiles to offer support for such protests, particularly during major national events, exiles are no longer able to participate directly. For that reason we expect them to be less engaged in organizing events and less likely to discuss more local protest activities.

Third, we expect that the nature of criticisms targeting the regime will change, becoming increasingly harsh. Criticisms of the Maduro government are highly varied, but we focus on several categories that we consider particularly severe. First, the Maduro government is often tied to narco-trafficking, linked to the alleged Cartel de los Soles run by high-ranking members of the government (Rashbaum, Weiser, and Benner Reference Rashbaum, Weiser and Benner2020). Second, because of his attempts to subvert checks and balances on his power, Maduro is frequently accused of fascism. Third, critics attack the “hijacking” or “invasion” of Venezuela by Russian and Cuban agents supporting the current regime (Borges Reference Borges2019). Fourth, as described, Maduro frequently uses extrajudicial methods of repression to silence opponents. These criticisms are largely, if not entirely, based in truth, particularly given Maduro’s widespread human rights violations. We argue, however, that they represent broad, severe, and national-level attacks on the regime, both more interpretable by international audiences and reflective of exiles’ greater outspokenness.

We also expect to find evidence for one primary mechanism behind our theory: the internationalization of activists’ networks. With socialization into new communities and changing opportunities for influence, we expect activists to increasingly use rhetoric targeted at international audiences. A core component of our theory posits that activists will increasingly interact with and appeal to international actors after exile. Interaction with citizens of host countries should be particularly likely to increase, as these individuals should be the primary target of activism. For example, Venezuelan opposition leaders living in Miami should be more focused on US action against Venezuela than those living in Bogotá.

Data and Methods

To understand the relationship between exile and online political discourse, we draw on original data on the exile of Venezuelan opposition activists. We collected more than 5 million tweets posted by opposition leaders since 2013.Footnote 7 We then estimate the effect of exile on different topics of interest—foreign policy, domestic grievances, and harsh criticism of the regime—using difference-in-differences models and event study analyses. We describe our data and methods in greater detail below.

Data

Venezuelan Opposition

To explore the relationship between exile and discourse on Twitter, we first identified well-known Venezuelan opposition activists. We included all opposition deputies who served on Venezuela’s National Assembly (established in 2000), which is the most influential governing body on which opponents serve; opposition mayors elected in the last two cycles, since 2013Footnote 8; and prominent unelected activists and journalists who are publicly recognized as regime opponents. Because we identified the latter through searches of public news sources, we show in Appendix B3 that results hold using the more regularized sample of elected politicians. We coded each individual for whether they were in exile, the date they left Venezuela, and their destination internationally. Where date of exile could not be precisely determined, we used the date of the first news article listing the individual as living in exile.

Because our focus is on how exile affects online political discourse, we then collected activist Twitter handles, excluding those who did not have an account or who have not tweeted since 2013. This left us with a sample of 357 opposition leaders who were active on Twitter as of May 2020, of whom 94 were exiled.Footnote 9 The majority of those exiled (86) left after Maduro took office in 2013. After our data collection ended, Maduro granted pardons to a number of opposition members living in exile, but in our sample just two activists returned to Venezuela.Footnote 10

Exile is difficult to measure, and often encompasses a wide range of reasons for individuals fleeing their home countries. For example, estimates for Chilean exiles during Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship range from several thousand to 200,000, the latter including those who fled not because of direct pressure but due to political and economic concerns (Esberg Reference Esberg2021). Though most of the Venezuelan exodus fled due to economic collapse, they are still often referred to as Venezuelans “in exile.” Recognizing the difficulty of operationalizing exile, we adopt a broad, neutral measure: we include any activist in our dataset who had left Venezuela at the time of data collection. In practice, however, this decision is rarely voluntary. Many exiles are forced out through harassment, such as threats of detention, but pushing them abroad may have been what the regime intended (Wright and Oñate Zuñiga Reference Wright and Zuñiga2007). For example, Guaidó was threatened with charges during a brief period outside the country in 2019, but those threats seemed designed to force him into exile; he has not yet been charged, and remains in the country. Among the exiled whose reason for leaving the country we could identify, 44 preemptively fled detention, violence, threats, or prosecution; 33 were forced out by the regime through unspecified measures; six fled for political reasons; and three were barred from reentering after going abroad. Just three identified as being in voluntary or self-imposed exile.

Our sample is not exhaustive, and our results can best be interpreted as how exile influences the online discourse of opposition elites. Because we collected our list of opponents through internet searches, we likely missed many activists operating locally outside of major cities. This also means our sample may bias toward wealthier elites, which affects their ability to leave the country and the host countries where they settle.Footnote 11 We also cannot know the degree to which our sample is representative of the broader diaspora, though we expect political actors to be particularly strategic in shifting their online discourse to reflect their new positioning. However, this population of political elites is of great interest to the regime and to the international community, as these more prominent national-level political figures are the most visible outside the country.

Twitter Data Collection

Once we identified our sample of 357 opposition leaders who had active Twitter accounts, we used Twitter’s Historical Power Track API to collect their tweets from January 1, 2013, until May 31, 2020, when we began collecting data. This API provides access to the entire historical archive of public Twitter data—dating back to the first tweet—using a rule-based filtering system to deliver complete coverage of historical Twitter data. This yielded a dataset of 5,299,214 tweets.

Accounts in our dataset have an average of 35,021 followers and 4,123 friends. Most accounts in our dataset have been on Twitter for a long time—3,345 days or almost 10 years on average. Tweets sent by these accounts receive high levels of engagement. We find that on average each users’ tweets in our data are retweeted 626 times and liked or favorited 870 times, demonstrating the importance of Twitter to Venezuelan politics. In addition to our data-collection approach, which involved manually identifying each account, the fact that the accounts we identified have been active for a long time, have large followings, and high levels of engagement increases our confidence that they are authentic Twitter users—rather than bots or trolls.Footnote 12

Topics

Our primary outcome variables are the percentages of opposition leaders’ tweets that reference several central topics: foreign action (meaning diplomacy, sanctions, or military intervention); local grievances related to the provision of services; protest; and harsh regime criticism, meaning content related to accusations of narco-trafficking, fascism, Cuban or Russian invasion, and extrajudicial repression. We additionally test whether exile changes the networks of those outside Venezuela. Among other ways of illustrating this mechanism, we track references to foreign actors.

To identify topics in our data, we use a word2vec model (Mikolov et al. Reference Mikolov, Chen, Corrado, Jeffrey Dean and Zweig2013) trained on the entire corpus of tweets in our dataset. This includes both English- and Spanish-language tweets, the most common languages in the data, to reflect the fact that the language used by exiles may change as well.Footnote 13 Word2vec models produce word-embeddings built on shallow neural networks, which rely on the collocation of words in texts to create vectors of terms that represent each word. They have been shown to capture complex concepts from analogies to changing cultural meanings and stereotypes associated with race, ethnicity, and gender (Rodman Reference Rodman2020). In particular, we begin with a set of seed words that we identify as being relevant to the concept of interest (e.g., “manifestación” for protest). We then used word embeddings to identify other words that are semantically related to our seed words in the data. Semantic similarity here is based on these words appearing in similar contexts and can be computed using cosine similarity on the word-embedding space (Gurciullo and Mikhaylov Reference Gurciullo and Mikhaylov2017). These dictionaries are then limited to the 100 most similar words, and we remove overly general or irrelevant terms.Footnote 14 Expert validation of tweets classified as referencing foreign action, protest, criticism of the regime, and service provision using our word2vec dictionary method suggests that between 93% and 97% of tweets were accurately classified across the four topics.Footnote 15 For foreign intervention and sanctions, both controversial policy options, we additionally train a classifier to specifically identify support for these policies.Footnote 16

Empirical Strategy

Fixed Effects Models

To identify the relationship between exile and online behavior, we exploit both variation between exiles and those who remain in country and changes in exiles’ behavior in the months before and after they leave Venezuela. Our main analyses transform our tweet-level dataset into a panel by aggregating posts to the month-individual level, which helps prevent unduly weighting the tweets of frequent posters. Our main dependent variables are the percentages of tweets related to a given topic or subtopic (for example, the percentage of tweets by an opposition leader in a given month referencing sanctions). The median number of tweets per month for activists in our sample is 98.Footnote 17

Our main specification uses two-way fixed effects to estimate the relationship between exile and online dissent while accounting for common time shocks and time-invariant user characteristics. Our independent variable is whether a user was in exile in a given month, and our main dependent variable is the percentage of posts on a given topic:

The coefficient of interest is

![]() $ {\beta}_1 $

, representing the effect of individual i’s exile on tweeting about this topic, and Yit is our dependent variable, the percentage of posts about a given topic that individual i tweets in month t. The primary independent variable is

$ {\beta}_1 $

, representing the effect of individual i’s exile on tweeting about this topic, and Yit is our dependent variable, the percentage of posts about a given topic that individual i tweets in month t. The primary independent variable is

![]() $ {Exile}_{it}, $

a binary indicator for whether an individual spent that month in exile.

$ {Exile}_{it}, $

a binary indicator for whether an individual spent that month in exile.

![]() $ {\lambda}_i $

are individual fixed effects, which account for time-invariant characteristics;

$ {\lambda}_i $

are individual fixed effects, which account for time-invariant characteristics;

![]() $ {\eta}_t $

are month fixed effects, which account for common time shocks; and

$ {\eta}_t $

are month fixed effects, which account for common time shocks; and

![]() $ {X}^{\prime } $

is the (log) number of tweets per month, accounting for variation in rates of tweeting. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

$ {X}^{\prime } $

is the (log) number of tweets per month, accounting for variation in rates of tweeting. Standard errors are clustered at the individual level.

The central requirement for interpreting results causally is that exiled activists would have, in the absence of treatment, behaved similarly to those who remain in country. Although an untestable assumption, in traditional difference-in-differences designs, we may support this by demonstrating parallel trends before treatment. As our treatment is staggered, we can use an event study design, which replaces the binary independent variable with leads and lags for the months until or since exile:Footnote 18

$$ {Y}_{it\hskip0.35em =\hskip0.35em }{\beta}_0+\sum \limits_{\genfrac{}{}{0pt}{}{n=-6}{n\ne -1}}^{n=11}{\beta}_n{I}_{it}^n+{\lambda}_i+{\eta}_t+{\beta}_2{X}^{\prime }+{\varepsilon}_{it}. $$

$$ {Y}_{it\hskip0.35em =\hskip0.35em }{\beta}_0+\sum \limits_{\genfrac{}{}{0pt}{}{n=-6}{n\ne -1}}^{n=11}{\beta}_n{I}_{it}^n+{\lambda}_i+{\eta}_t+{\beta}_2{X}^{\prime }+{\varepsilon}_{it}. $$

We include dummies

![]() $ {I}_{it}^n $

for the six months prior to exile and the 12 months following, comparing them to the month directly prior to an individual leaving the country. Thus,

$ {I}_{it}^n $

for the six months prior to exile and the 12 months following, comparing them to the month directly prior to an individual leaving the country. Thus,

![]() $ {\beta}_n $

are the n − 1 coefficients of interest,

$ {\beta}_n $

are the n − 1 coefficients of interest,

![]() $ {\lambda}_i $

are individual fixed effects accounting for time-invariant characteristics, and

$ {\lambda}_i $

are individual fixed effects accounting for time-invariant characteristics, and

![]() $ {\eta}_t $

is month fixed effects, to adjust for common time shocks. As above, we include the log number of tweets in a given month. Estimated lead coefficients that are nonzero suggest violation of parallel trends. This also allows us to see the dynamic effects of exile over time. As event studies are less appropriate for rare outcomes, we show these plots only for the major categories we track (calls for foreign action, discussion of protest, criticism of the regime, and mentions of foreign actors).

$ {\eta}_t $

is month fixed effects, to adjust for common time shocks. As above, we include the log number of tweets in a given month. Estimated lead coefficients that are nonzero suggest violation of parallel trends. This also allows us to see the dynamic effects of exile over time. As event studies are less appropriate for rare outcomes, we show these plots only for the major categories we track (calls for foreign action, discussion of protest, criticism of the regime, and mentions of foreign actors).

Still, exile is nonrandom, dependent on characteristics of the activist and more likely during periods of regime instability. Exile may target those members of the opposition most likely to be affected by leaving the country: for example, the government may want to push out particularly stringent or outspoken opposition activists, but they may be the most likely to even more vociferously criticize the government when safely overseas. The regime may force an individual to flee because they were increasingly critical of Maduro, in which case we may see a spurious relationship between exile and behavior. In addition to exploring pretrends and anticipation effects in our event study design, however, this concern is lessened by the nature of our sample: these are individuals whose political beliefs are widely known and who openly stand with the opposition.

To provide further confidence in the results, we show that results hold when including an individual-specific linear time trend, which accounts for possible activist-specific trends in the dependent variable. Given concerns about the interpretation and validity of two-way fixed effects, we also show pooled results that control for month but not unit fixed effects to account for major nation-wide events like protests and elections (Imai and Kim Reference Imai and Kim2020). In Appendices B7–B8, we additionally show the results of robustness tests related to new literature on the problems of staggered treatment timing in difference-in-differences designs.

Results

This section provides evidence that exile significantly increases Twitter discussions of foreign policy solutions to Venezuela’s crisis and harsh criticisms of the regime; in contrast, it reduces discussions of local grievances and protests. In line with our theory, this suggests that exile shifts opportunities for dissent and influence, leading activists to target their messages more to foreign than to domestic audiences. To provide further evidence for this mechanism, we demonstrate that across multiple metrics exile is associated with a significant increase in discussions of and interactions with foreign entities.

Calls for Foreign Action

We argue that exiles increasingly turn to foreign-led solutions to Venezuela’s crisis. In order to demonstrate this, we built word2vec dictionaries related to three major foreign policy options proposed for Venezuela: military intervention, sanctions, and diplomacy. Military intervention encompasses references to foreign military involvement by the United States or an international coalition, both direct and indirect (e.g., “all options are on the table”); naval blockades; and forceful humanitarian intervention. References to military intervention are in general quite rare, with 0.12% (6,257) of our 5 million tweets mentioning them. Sanctions include both targeted and generalized sanctions against the regime or the country, totaling 0.54% of tweets (28,385). Diplomacy includes references to diplomatic efforts, international pressure, international dialogue, or an internationally negotiated transition, and 1.33% of tweets (70,471) discuss international diplomatic efforts. Example tweets about foreign-led policies include the following:

-

• A military intervention by nationals supported by foreigners would not be a setback from the current situation. The setback would be to let criminals continue to exterminate our population and to only confront them with non-violence #LibertyOrNothing.

-

• Despite the efforts of those linked to the #Caracas regime in #WashingtonDC to eliminate the sanctions, the administration of @realDonaldTrump continues to punish members of organized crime that govern #Venezuela #Sanctions #Justicia

-

• RT @jguaido: At last I can report that we have already established contact with our international allies to evaluate collaborative proposals for Venezuela. We are looking for help for our people.

Figure 1 demonstrates that references to foreign policy actions increase significantly with exile. Within the first two months of leaving the country, they became significantly more likely to discuss international policy solutions for the Venezuelan crisis, and this effect persists for a full year after exile. The left panel shows coefficient plots for our fixed effects models (two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects with a unit-specific linear time trend, and month fixed effects only). Results show the percentage-point change in discussions of each topic after exile, relative to activists who remained in Venezuela. Although some of these changes appear quite small, relative to the amount the topics are discussed, the substantive effects are sizable. Overall, after exile the percentage of activists’ tweets focused on foreign policy topics more than doubles.

Figure 1. Exile and Discussions of Foreign Action

Note: Left panel: Coefficient plots for models using two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects plus a unit-specific time trend, and month fixed effects only. Right panel: Event study plots estimating leads and lags for exile, using the month immediately prior as the comparison period. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are robust and clustered at the individual level. Results demonstrate that exile is associated with a significant increase in discussions of foreign policy solutions for Venezuela’s crisis. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A1 and A7 in the Appendix.

Although these results are driven by all mentions of these foreign actions identified using our dictionary approach, they do not automatically express a policy position. Even though reading the tweets in our dataset suggests that references to diplomacy are almost always positive, positions expressed about military interventions and sanctions, two aggressive and controversial foreign policy measures, are more diverse. Exiled individuals might be increasingly arguing against these policies, arguing for them, or neutrally sharing information related to these options. To test this, we hand-coded a set of 2,000 tweets identified as relating to military intervention and 2,000 tweets related to sanctions, asking coders to assess whether (1) a particular tweet was relevant to the topic and (2) whether it spoke of military intervention or sanctions positively, negatively, or neutrally (see Appendix A4). We then trained naive Bayes classifiers to first ascertain whether tweets were relevant to either military interventions or sanctions and then to label each tweet about military interventions or sanctions according to the sentiment it expressed.

This enables us to see that our results are mainly driven by an increase in supportive statements related to military intervention and sanctions, suggesting that exiled activists increasingly espoused aggressive foreign policy measures. Of tweets referencing military intervention, we identified 88.3% as relevant; of these, 58.2% spoke positively and 14.2% spoke negatively of military intervention. Regarding sanctions, 90.8% of tweets we initially identified as mentioning sanctions were classified as relevant, with 34.7% supportive of sanctions and 2.7% referencing them negatively.Footnote 19 More formally, we demonstrate in Appendix A5 that our results hold when including only statements positively referencing aggressive foreign policies. Exiles do not simply engage more with these policies; they make more public statements in support of such actions.

Our results also provide some descriptive evidence that the feasibility of different foreign policy options affects uptake by members of the opposition. Appendix A2 shows the rate of discussion for our topics over time. Breaking this down further by type of foreign policy, we see an increase in discussions of military action when Trump is president—providing suggestive evidence that the effects discussed here will vary by the foreign policy options considered available to exiles.

Local Grievances

Our theory additionally suggests that exile should change the degree to which opposition figures focus on issues and activism at the local level. Just as exiles may recognize the new opportunities afforded by going abroad, old pathways of influence may be less effective from outside of the country. Activists abroad should also be less aware of specific local events on the ground and less active in organizing domestic opposition directly. Opponents frequently criticize the Venezuelan government for widespread hunger, lack of water, intermittent electricity, gas shortages, and other failures to provide basic services; 5.6% of tweets (294,447) reference the provision of such services. Examples include “The government shows, once again, its inability to operate and maintain public services” and “Because of years of abandonment by @Hidrocentro2011, today we Carabobeños live a tragedy, more than 20 days without water in our communities #CaraboboSinAgua.”

We additionally argue that exiled activists will be less focused on domestic mobilization. Opposition figures abroad are no longer present to organize and participate in collective action and should thus discuss it less. Although Venezuela has a strong history of national protests, many happen at a much smaller scale in response to local issues (BBC 2020). We expect that differences between activists at home and abroad will largely be driven by the degree to which domestic activists are involved in organizing protests and engaging in local collective action. Exiles are likely to remain more engaged in major and national protest, including through tweets of support. Although difficult to test quantitatively, qualitative evidence offers some support. An example tweet about protest reads, “We are now arriving at #Chacaito alongside the brave people of #Caracas to join this concentration. #100DaysOfResistanceForVenezuela.” Another post states, “#TACHIRA. San Pedro del Rio, Autopista San Cristóbal-La Fría, reported road closure due to protest against the shortage of domestic gas and continuous electricity cuts.”

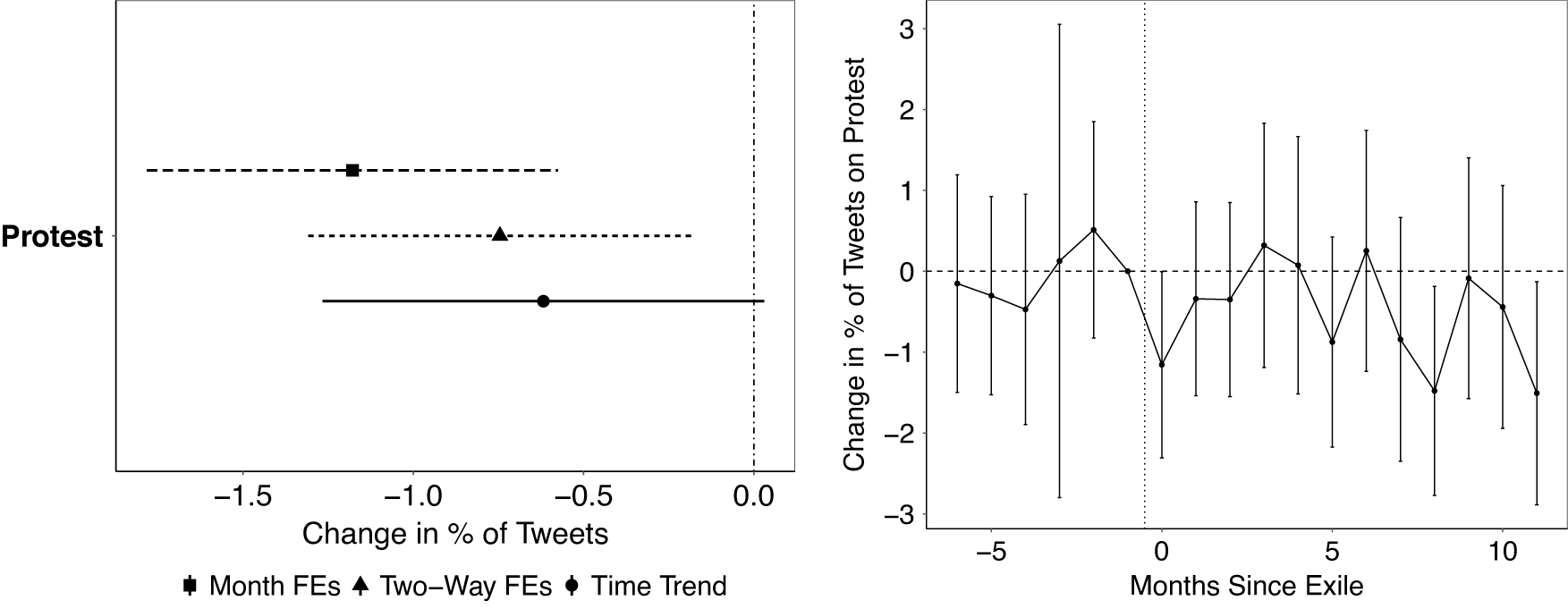

Figure 2 demonstrates that criticisms related to service provision drop significantly after exile, an effect that persists through the following year. Relative to the mean rate at which these topics were discussed, service-provision-related criticisms dropped by about half. This suggests that exiles become less focused on these local grievances as their international networks strengthen and their connection to local politics is reduced. Figure 3 shows that exile is associated with a decrease in discussion of domestic protest. The effects are smaller and noisier than those we identified for foreign actions or service provision. Nevertheless, our main specification suggests that there is an approximately 0.75 percentage-point drop in discussions of protest after leaving the country compared with an overall mean of 4.9% of tweets (260,086) referencing mobilization.

Figure 2. Exile and Service Criticisms

Note: Left panels: Coefficient plot for models using two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects plus a unit-specific time trend, and month fixed effects only. Right panel: Event study plots estimating leads and lags for exile, using the month immediately prior as the comparison period. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are robust and clustered at the individual level. Results demonstrate that more domestically focused critiques of service provision fall after exile. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A2 and A7 in the Appendix.

Figure 3. Exile and Protest

Note: Left panel: Coefficient plots for models using two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects plus a unit-specific time trend, and month fixed effects only. Right panel: Event study plots estimating leads and lags for exile, using the month immediately prior as the comparison period. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are robust and clustered at the individual level. Though results are noisy, they demonstrate a drop in discussions of mobilization after exile. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A3 and A7 in the Appendix.

Criticism of the Regime

We expect that exile should also be associated with an increase in harsh criticisms that target the legitimacy of Maduro’s regime directly. Such criticisms can be more safely made from abroad than domestically, and they may be more appealing to international audiences. We track four types of harsh criticisms. Narco-state criticisms, which make up 2.15% of tweets (113,781), focus on references to narco-trafficking and Maduro’s links to drug money. Dictator criticisms focus on accusations of fascism or dictatorship, making up 4.96% of tweets (262,670). Cuban/Russian Influence critiques play up the role of Cuba and Russia in supporting the Maduro regime and appear in 1.86% of tweets (98,671). Repression tweets make up 7.4% of tweets (392,112) and reference political killings, disappearances, imprisonment, torture, home searches, and other forms of state violence. Footnote 20 Example tweets include:

-

• 7,186,170 Venezuelans vote YES to democracy, YES to the Constitution, YES to Nicolás Maduro’s narco-regime leaving Miraflores.

-

• This prosecutor is used by and part of the Repressive Structure of Maduro the Usurper, he will never appoint prosecutors to investigate the murder of protestors, extrajudicial executions, torture, etc.

-

• The Venezuela problem is not just political, as we face a dictatorship supported by Russia.

Figure 4 demonstrates that harsh criticism of the regime increases with exile. This aligns with both reduced self-censorship among activists and the potential strategic adjustment of criticisms to focus more on critiques of interest to international audiences. The flow of cocaine through Venezuela, and high-level Venezuelan officials’ involvement in the drug trade, is of particular importance to U.S. policy makers, for example (Ramsey and Smilde Reference Ramsey and Smilde2020).

Figure 4. Exile and Criticism

Note: Left panel: Coefficient plots for models using two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects plus a unit-specific time trend, and month fixed effects only. Right panel: Event study plots estimating leads and lags for exile, using the month immediately prior as the comparison period. Standard errors and 95% confidence intervals are robust and clustered at the individual level. Results suggest an increase in stringent criticism after exile. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A4 and A7 in the Appendix.

Our sample of activists in Venezuela is not exhaustive, and there may be concern that there is a fundamental difference between the treated and control groups that drive our findings. To reduce these concerns, in Appendix B3 we demonstrate that results hold when using only our most complete set of activists, elected deputies and mayors. We also show that the results hold when including only those elected more recently (since 2011), in case parts of our sample left politics (Appendix B3). To rule out that periods of imprisonment, especially those preceding exile, might be driving our findings, we additionally demonstrate that our results hold when excluding opposition activists imprisoned during the period under study (Appendix B4). Given variation within the Venezuelan opposition, we additionally demonstrate that results hold when controlling for politicians’ parties interacted with a linear time trend or when restricting our sample only to members of the more hardline Voluntad Popular party (Appendix B5). In addition, to ensure that our results are not being significantly skewed by a particular user or set of users, we show that results are stable when dropping each user in our sample in turn (Appendix B6).

Recent research has also raised concerns about the causal interpretation of two-way fixed effects difference-in-differences designs with staggered treatment timing when effects are heterogenous across time (which is often likely to be the case; Brantly and Sant’Anna Reference Brantly and Sant’Anna2021; Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2021; Imai and Kim Reference Imai and Kim2020). The central concern is that negative weights may be assigned when treatment effects and timing vary because already-treated units may serve as control groups. This is of somewhat less concern in our design because our sample of never-treated individuals is large, but we nevertheless perform several robustness checks to ensure the validity of our findings in Appendix B7. First, we show the results of a Goodman-Bacon decomposition, which demonstrates that our estimates are similar regardless of the timing of treatment and weights are similar across treatment periods. We then show results hold using the Callaway and Sant’Anna (Reference Brantly and Sant’Anna2021) estimator for a “dynamic” event study specification.Footnote 21 Additionally, we show that our results hold when excluding those who went into exile early (Appendix B9), prior to the start of our tweet data, and when including only those who were exiled later in the regime (after 2017). Moreover, our results hold using t-tests comparing the percentage of tweets by exiles about each topic in the period preceding and following exile (Appendix A8). Although simply descriptive, this helps reduce concerns that our results are driven by modeling decisions.

Mechanism: Increased Engagement with Foreign Actors

One pathway through which we expect exile to change the content of dissent is activists’ increased engagement with and focus on international communities. As their networks become internationalized, activists may tailor messaging to this audience and may increasingly engage with the policy options available to their host country. We provide evidence for this in multiple ways. First, Figure 5 shows that Foreign Terms (such as references to other Latin American countries, the US, and European nations) increase following exile. Although this measure encompasses many countries, we also show that mentions of the United States alone—the most popular destination country for Venezuelan exiles—increase. These effects begin shortly after exile and persist through the year, with no evidence of a pretrend in the event-study plot.

Figure 5. Exile and Foreign Actors

Note: Left panel: Coefficient plot for models using two-way fixed effects, two-way fixed effects plus a unit-specific time trend, and month fixed effects only. Standard errors and confidence intervals are robust and clustered at the individual level. Foreign engagement uses only tweets “@”ing a user self-reported to live in Venezuela or overseas. Right panel: Event study plot estimating leads and lags for exile, using the month immediately prior as the comparison period. Results demonstrate that references to and engagement with foreign actors increases following exile. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A5 and A7 in the Appendix.

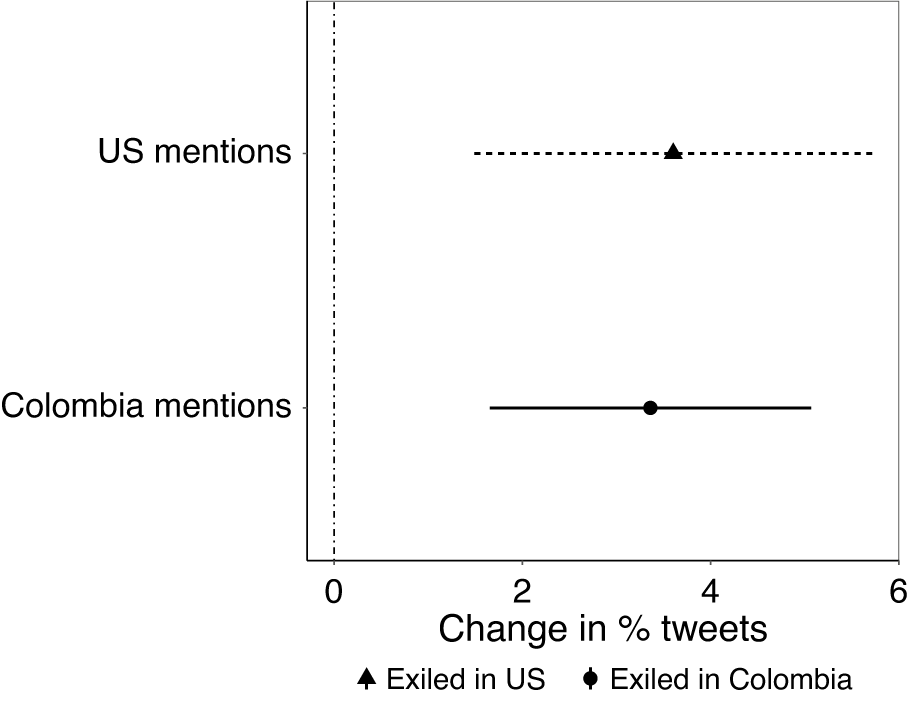

Figure 6. Exile and Destination

Note: Coefficient plot regressing mentions of common host destinations (the US and Colombia) on whether the user was in exile in that country in a given month. Coefficients show the effect of exile on mentions of the host country, relative to those in exile in other states. Models use two-way fixed effects with robust standard errors clustered at the individual level. Though all exiles are more likely to mention foreign nations, this effect is particularly pronounced for an activist’s host country. Tabular results are displayed in Tables A6 and A7 in the Appendix.

Second, the left panel of Figure 5 also shows the effect of exile on Foreign Engagement. To measure this, we collected the Twitter handles of all users that the activists in our sample tweeted at or replied to. Where available, we then used the self-reported location information to identify users who lived abroad or in Venezuela, restricting our sample to only those cases where location information was available. Our results demonstrate that exiled activists increasingly associated with Twitter users living abroad, confirming that their networks become more international. We also show that exiles are more likely to tweet in English, one signal of exiles strategically positioning themselves in the international community.

Finally, Figure 6 demonstrates that exile increases references to host-country nations. Using our coding of exiles’ destinations overseas, we interact our binary independent variable for whether a user was in exile in a given month with whether they live in the United States or Colombia, the most common destinations. Our dependent variables are references particularly to these nations. Overall, all exiles were more likely to reference foreign actors than those who remained in Venezuela. But relative to those who went to other countries, Venezuelans in the US were more likely to use terms relating to the United States; Venezuelans in Colombia were more likely to reference Colombia-related terms. In Appendix A7 we additionally explore results broken down by exiles’ host state. However, there are no significant differences between exiles living in the United States versus other locations, which may be a reflection of an underpowered sample when splitting exiles by destination or a degree of ideological similarity among the international networks and diaspora communities that exiles join.

Exiles and observers point to the effects of this internationalization—and particularly socialization into a new political community—as central to why leaving Venezuela changes expressed attitudes. The Venezuelan diaspora focuses a great deal on shaping foreign policy toward Venezuela, in the process becoming much more engaged with political actors in their host country (Noriega Reference Noriega2014). They also become more integrated into a broader diaspora: one former US official noted that for exiles, the diaspora “becomes their tribe and identification.”Footnote 22 Expressing more centrist views toward the Maduro regime abroad, one former exile noted, was “almost unacceptable.”Footnote 23 This is in part enforced through social media, and particularly Twitter, where deviation may be met with claims of “chavismo” (Padgett Reference Padgett2017).

This is not the only mechanism underlying the change in how exiles communicate. Exiles refer to weakened ties with on-the-ground politics as a source of the divergence in attitudes after leaving. Toro (Reference Toro2020) describes how, by situating activists out of the country, exile may lead to divergence between the opposition at home and abroad: “How dare [I] pass judgment … from the comfort of a Montreal exile, where the water always works, the power never goes out and nobody throws you in jail for thinking the wrong thought? … How dare anyone not in Venezuela do that?” Dissidents are also freer to express themselves, with one former politician explaining, “[outside Venezuela], there’s no political cost to doing or saying anything.”Footnote 24 Although reduced self-censorship and less fear of government reprisals certainly play a role in the findings documented here, it should be noted it is unlikely to be the only mechanism: it cannot alone explain the increased focus on foreign rather than domestic issues.

Conclusion

In this article, we demonstrate that exile changes how activists express dissent. Being overseas opens new opportunities to influence foreign governments and freely express themselves. However, it also weakens activists’ ties to local networks and reduces their awareness of day-to-day activities at home. As a result, we argue that going abroad should make exiles increasingly focused on foreign policies toward their home state, less attuned to local grievances, and more willing to be harshly critical of the regime. Drawing on an original dataset of Venezuelan opposition figures and their Twitter histories, we provide evidence in support of these theoretical expectations. We also find that these changes are in part due to the increasingly international networks that exiles join when they go abroad, showing across several metrics that activist engagement with foreign entities significantly increases following exile.

This article contributes to our understanding of the consequences of repression and the relationship between repression and dissent more broadly. Although decades of social science literature have explored the dissent–repression nexus, empirical findings have often been contradictory, prompting scholars to call for disaggregating by type of repression, by space, and by time to better explain the dynamic relationship between repression and dissent (Chenoweth, Perkoski, and Kang Reference Chenoweth, Perkoski and Kang2017; Davenport Reference Davenport2007; Davenport and Inman Reference Davenport and Inman2012; Davenport and Moore Reference Davenport and Moore2012; Pan and Siegel Reference Pan and Siegel2020). Our temporally granular individual-level data enable us to examine the political consequences of exile—a ubiquitous but understudied form of repression in the political science literature.

Research on how individuals respond to repression typically focuses on more violent methods, like detention or killings (Bautista Reference Bautista2015; García-Ponce and Pasquale Reference García-Ponce and Pasquale2015; Rozenas and Zhukov Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2013; Young Reference Young2020). However, exile fundamentally differs from these methods because opposition abroad often continue their activism in a different setting, with reduced fear for their physical integrity rights. A large body of research has highlighted how diaspora communities from a wide variety of home- and host-country governments have used brokerage, framing, ethnic outbidding, lobbying, coalition building, and the diffusion of ideas to shape foreign policies and alter outcomes in their home countries (Adamson Reference Adamson and Checkel2013; Adamson and Demetriou Reference Adamson and Demetriou2007; Girard and Grenier Reference Girard and Grenier2008; Koinova Reference Koinova2011; Reference Koinova2014; Koinova and Karabegović Reference Koinova and Karabegović2019; Moss Reference Moss2021; Shain Reference Shain1988; Reference Shain1994; Reference Shain2002). By focusing on well-known, elite dissidents—actors who are particularly well positioned to influence policy—and by quantitatively testing the effect of exile on individual-level behavior, our work provides an important contribution. Our study also adds to a growing body of work on the effects of repression on online dissent. This includes research examining a range of repressive strategies from arrests (Pan and Siegel Reference Pan and Siegel2020) to censorship (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013; Roberts Reference Roberts2018) and computational propaganda (Woolley and Howard Reference Woolley and Howard2018). Here, we provide the first large-scale, quantitative study of the effects of exile on online opposition.

Although our results are limited to the Venezuelan context, we expect our theory to hold for exiles emanating from repressive regimes, who share the goal of structurally changing their home-country government. Exiles or refugees who fled broader conflict should differ in their objectives and how they talk about their home countries. Members of distinct ethnic, nationalist, or social groups in exile may seek territorial or political change only for their population (Koinova Reference Koinova2009; Reference Koinova2014; Reference Koinova2021). For exiles fleeing repressive authoritarian or hybrid governments, however, we expect our theory to broadly apply—though we anticipate the specific ways in which discourse changes will vary based on home- and host-state context (Brinkerhoff Reference Brinkerhoff2016).

The types of foreign policy interventions that exiles advocate for will depend on feasibility, including how much they align with host-country foreign policy goals. In many cases these include similar calls for sanctions, military intervention, and diplomacy that we observed in the Venezuelan context. For example, in 2003 Myanmar’s exiled Prime Minister called for increased sanctions against the military government (Humhreys Reference Humhreys2003). A group of exiled Iranian dissidents supported the Trump administration’s policy of “maximum pressure,” including widespread sanctions (Behravesh Reference Behravesh2019). Cuban exiles have repeatedly called for similar interventionist policies (Grenier Reference Grenier2017), and Iraqi exiles notoriously lobbied for the 2003 US invasion of Iraq to depose Sadaam Hussein (Vanderbush Reference Vanderbush2009). For exiles from home countries that maintain close military or economic ties with the host state, calls for foreign action may focus on lighter-touch interventions, such as Saudi activists’ calls for Western governments and human rights organizations to condemn the kingdom’s human rights abuses (Nowairah Reference Nowairah2021). We expect that the degree to which more drastic action is feasible in a given home country will shape how extreme or moderate exiles’ demands are. This may be one reason why some past work suggests that exiles express more extreme positions (Koinova Reference Koinova2009) and other findings suggest that exiles are more moderate than those in the home country (Müller-Funk Reference Müller-Funk2016; Nugent Reference Nugent2020; Reference Nugent2022).

Although we expect moving abroad to make all exiles less connected to local networks and developments in their home countries, the degree to which exiles discuss local grievances and activism after exile may be shaped by the level of home-state control over speech. Restrictions on free speech affect the baseline rate at which dissidents at home can discuss certain topics related to local activism: for example, discussions of collective action are actively censored in China, though discussion of other grievances are allowed (King, Pan, and Roberts Reference King, Pan and Roberts2013). We might expect changes in the rate of discussions of local protest to look different if exiles are exiting a high-censorship environment than a lower-censorship environment. Discussion of local grievances and activism may also be moderated by exiles’ perceived likelihood of return.

Finally, we expect that home-state capacity for transnational repression may shape the willingness of exiles to harshly criticize the regime from abroad (Adamson Reference Adamson2020; Adamson and Tsourapas Reference Adamson and Tsourapas2020; Dalmasso et al. Reference Dalmasso, Del Sordi, Glasius, Hirt, Michaelsen, Mohammad and Moss2018; Tsourapas Reference Tsourapas2021). Fear of repression abroad has been found to dampen antiregime opposition among the Syrian, Libyan, and Yemeni diaspora communities, for example (Moss Reference Moss2021). Among elite exiles, however, we might not observe the same dampening that researchers have found in the diaspora as a whole. Because elite exiles have long been well known to their home-country regimes and faced severe threats that prompted them to leave the country, they will likely still feel freer to express criticism from abroad. Along these lines, Saudi activists have heavily criticized the regime and directly called out King Mohamed bin Salman for abuses even after the death of Jamal Khashoggi highlighted the regime’s ability to target dissidents abroad (Nowairah Reference Nowairah2021).

Considering the generalizability of our results opens up a number of avenues for future research on the relationship between exile and dissent. First, we provide some descriptive evidence that opposition members tend to shift their rhetoric strategically in response to home- and host-country conditions. Future research should explore when and how diaspora communities’ political goals shift. Second, authoritarian regimes have increasingly cut off access to social media sites for long periods; future research could explore how this changes who dissents online. Third, countries differ in the degree to which exile is a legal versus an ad hoc instrument. Although in Venezuela most activists were forced out through threats or intimidation, future research could explore how different forms of exile affect changes in rhetoric. Fourth, the effects of exile may vary by continued vulnerability to the repressive regime. For example, exiles whose families remain in the home country or who have significant assets there may be more wary of changing their rhetoric. Additionally, future research should continue to explore how exile communities evolve over time and across generations—research begun with the study of Cuban Americans (Grenier Reference Grenier2017). We hope that future work will draw on similar methods and data sources in diverse global contexts to advance our understanding of how one of the most ubiquitous forms of repression is shaping dissent in the digital age.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001290.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/3RWCPB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For helpful feedback, we would like to thank Ivan Briscoe, Tarek Ghani, Phil Gunson, Dorothy Kronick, Renata Segura, Lauren Young, Stanford’s Immigration Policy Lab, UPENN’s Comparative Politics Workshop, University of Washington’s Seminar in Comparative Politics, WZB Berlin’s Social Science Center, UCLA’s Politics of Order and Development Lab, and members of the WUSTL Methods Lab. Emma Li, Beatriz Teles, Emily Schultis, and Emily Tomz provided excellent research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.