Introduction

On March 13, 1995, a commemorative plaque displayed on a monument located eighty kilometers north of Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, was destroyed, and the names inscribed on it were erased. This plaque had been placed there by the colonial administration in memory of those who had lost their lives in the Battle of Um Tounsi in 1932, in which colonial troops (with the support of local military personnel) clashed with fighters from the northern boundaries of present-day Mauritania. The instigators of this destruction were the descendants of some of those who died at Um Tounsi, who claim that their intention was to erase the traces of a shameful past, as the plaque served as a reminder that their ancestors fought alongside colonial forces (see Figure 1). This incident epitomizes the ambiguity of feelings still evident today toward Mauritania’s colonial legacy. It also illustrates the intricacy and pervasive character of this historical period, a century after the implementation of colonial rule and more than half a century after the country’s independence in 1960, as the descendants of the Mauritanian participants of that colonial battle reenact this clash in the national parliament and in different media outlets.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Um Tounsi’s colonial monument 80 kilometers north of Nouakchott (Photo by Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba)

The media freedom unleashed after the end of the long rule of President Maaouya Ould Sid’Ahmed Taya (1984–2005) reached its apex in January 2012, when broadcasting licenses were granted to various private television and radio stations.Footnote 2 Since then, the controversy surrounding the Battle of Um Tounsi (and Mauritania’s colonial past more generally) has intensified substantially. One of the results of this unprecedented media freedom has been the propagation of views defending the—seemingly forgotten—Mauritanian resistance (muqawama in Arabic) to French colonization.Footnote 3 Through often-virulent verbal attacks, various people have been accused of having “collaborated” with the colonial authorities. Further exacerbating this tension, many television and radio stations have felt compelled to give air time to commentators who, in the most bitter terms, openly accused a specific region of the country and/or a particular community (e.g., the Trarza/El Gibla region of southwestern Mauritania and its “religious”/Zwāya status groups; see Figure 3) of being traitors and “lackeys” of France. This verbal aggression caused a chain reaction, giving rise to what we term a “negationist” discourse, meaning the attempt of anti-resistance voices to question the commonly accepted facts and the quasi-hegemonic nature of the current “resistance narrative.” Using similar media platforms (i.e., newspaper columns, social media, and web pages), voices rejecting the very existence of resistance to colonization started to emerge. This debate is not new in Mauritania, but the public dimension it has recently attained has transformed it into a de facto national debate.Footnote 4

The actors and the motives behind this current public outburst elude a precise definition. One can confidently discern, however, a state-sponsored effort to inscribe the resistance narrative in media and political agendas. The outgoing president of Mauritania, Ould Abdel Aziz, personally delivered speeches addressing this topic. Furthermore, the majority of those defending the muqawama as a decisive moment in the country’s history can be traced back to the government and its supporters. Conversely, a large number of voices denying the existence of an effective resistance movement in colonial Mauritania belong to the political opposition to the current presidency of Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, who assumed office in August 2019 and who continues the agenda of Ould Abdel Aziz.

Further complicating this controversy, this debate also engages with the widely known western Saharan tripartite social design (Stewart Reference Stewart1973). Remarkably, those supporting the resistance debate are predominantly from the northern and eastern regions of Mauritania and bear an Hassān (“warrior”) social status, while those denying the significance of this debate belong mostly to Zwāya (“religious”) status groups hailing from southwestern Mauritania. Without attempting to simplistically reduce this debate to a binary social partition, which has been abundantly questioned (Bonte Reference Bonte1989; Cleaveland Reference Cleaveland1998; Harrison Reference Harrison1988:38), the inescapable presence of the Hassān/Zwāya historical rivalry reflected in the contemporary “resistance debate” must nonetheless be acknowledged. As we will later demonstrate, while providing elements of comparison with neighboring countries and with parallel situations in Europe, the evocation of this debate remains eminently local in character and clearly tied to the historically deep-rooted Saharan social landscapes.Footnote 5

To the best of our knowledge, the existing body of academic discussion on this topic—the rivalry between Hassān and Zwāya status groups—predominantly relies on historical documentation. We draw rather on other elements, analyzing, in particular, documents emanating from different media outlets such as newspapers, radio, TV shows, and social media. Our approach is important insofar as it incorporates a significant corpus of non-referenced bibliographical materials, largely published online on Mauritanian media platforms or newspapers. This methodological option effectively broadens the scope of available sources on contemporary Mauritanian debates and authors. It should also classify and validate such sources as significant elements in the understanding of regional history. Our selection incorporates the authors—often with a limited track record of published materials (books)—who, through their public voices (in Arabic and French), have more clearly delineated the muqawama controversy.

The reading suggested here is less concerned with history-centered Saharan scholarly debates and more with the contemporary display and use of such argumentation, and in this respect it echoes some of the decolonizing knowledge debates gripping many parts of Africa and beyond. Public challenges to historical narratives, particularly the way that colonial legacies are remembered, memorialized, contested, and disrupted, inform our narration of the Mauritanian debates (e.g., Mamdani Reference Mamdani2016; Mignolo Reference Mignolo2011; Nyamnjoh Reference Nyamnjoh2016). We claim, nonetheless, that Mauritanian particularities, especially the impact of the recent loosening of media controls, have greatly impacted the understanding of Mauritania’s distant as well as its more recent (colonial) past. This article begins with a theoretical introduction to the memory debate, particularly as it relates to Mauritanian so-called resistance; we then discuss key actors associated with the “resistance” on Mauritanian media platforms and analyze their main ideas. The article concludes with a focus on the political instrumentalization that has taken place with regard to this controversy, particularly in light of recent decisions by the Mauritanian parliament.

History, memory, and politics

Debates about memory have been extensively explored by philosophers and historians (Bédarida Reference Bédarida2001; Nora Reference Nora1984; Ricœur Reference Ricœur2000); these scholarly exercises provide us with a set of tools that allows us to address the Mauritanian resistance debate, as well as this country’s (late) discussion of its colonial past and of its present as an independent state.

Memory debates involve memorial places and chosen historical episodes. They generally embrace political motivations and tend to be instrumentalized. These memorialized topics then are publicly discussed through different media outlets as well as in academic publications. The creation of memories often pertains to issues of identity—concerning policies of national definition, or the interests of a specific group—through the selection of a particular episode that is either glorified or denigrated. The construction of memories is often based on the idealized conception a group or a community has about its past, which can be either negative (victimization) or positive (glorification). When making its claims, a community opens itself to be challenged by other groups with contradictory views regarding the episode at hand. These opinions tend to generate a conflicting version of the same event, causing what Pascal Blanchard and Isabelle Veyrat-Masson (Reference Blanchard and Veyrat-Masson2008) have called “the war of memories.”

Generally speaking, the relationship between history and memory, though closely related, differs in nature, objectives, and means. Pierre Nora accurately defines memory as a domain that “filters, accumulates, capitalizes, and transmits,… erases and recomposes at will, according to the needs of the moment” (Blanchard & Veyrat-Masson Reference Blanchard and Veyrat-Masson2008:337). The work of memory is thus resolutely subjective and partial, sometimes simply representing a manipulation of history (Klein Reference Klein2000); it can also be oriented toward oblivion and the rejection of certain episodes. Through this selective work, a community can either rewrite or conceal part of its history. The work of memory thus participates both in a “strategy of forgetfulness as well as remembrance” (Gensberger & Lavabre Reference Gensburger, Lavabre and Müller2005:8). Enveloping the known parameters of “forgetfulness” or “reminiscence” (Étienne Reference Étienne2006), the state is many times a protagonist in the making of memories (or, in fact, history; see Trouillot [Reference Trouillot1995]). This stance, sometimes embodied in memorial laws, can aggravate an already strained landscape of conflicting opinions (see Figure 2).Footnote 6

Figure 2. Avenue de la Résistance, Rachid, Mauritania (Photo by Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba)

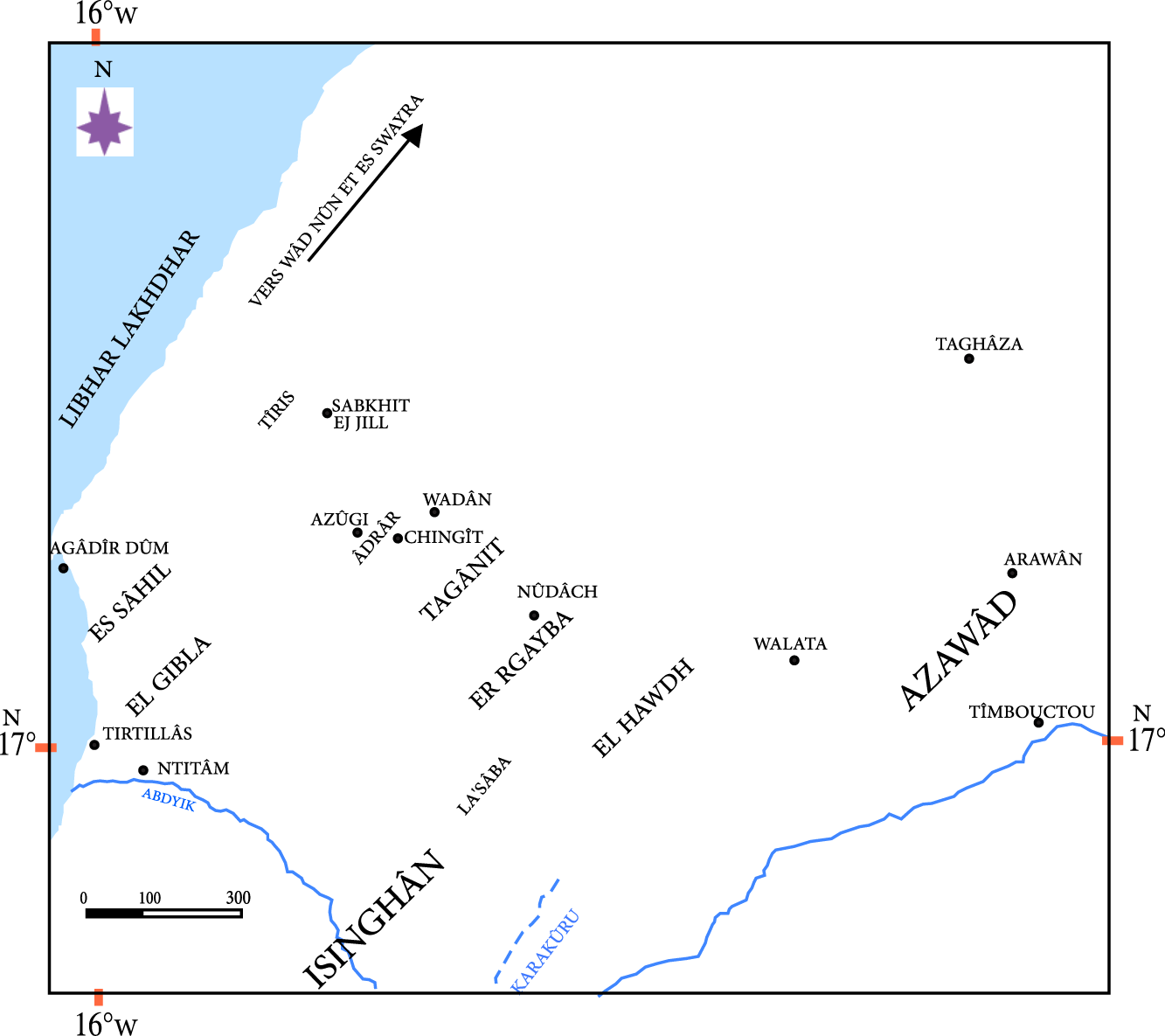

Figure 3. Map representing the Bidhan geographic aire d’influence

The fate of the Um Tounsi’s monument described above epitomizes the ambivalent approach of certain segments of society toward the remembering of a particular event. Those who destroyed this memorial plaque wanted to forget an episode that was disadvantageous for them, while others, observing the same event, reiterated the implausibility of any resistance movement against French colonial rule in Mauritania.Footnote 7

Attempting a reading of the region’s colonial past, one cannot overlook recent events in neighboring Senegal. In contrast to events in Mauritania—where the Um Tounsi’s memorial plaque has not been rehabilitated and the whole monument is today practically in ruins—in Senegal the statue of the former French governor of the colony, Louis Faidherbe, initially erected in 1886, was restored to public space in 2017, with the inscription: “To its governor, L. Faidherbe, Senegal is grateful.” In fact, the Senegalese government ordered the mayor of the city of Saint-Louis to repair Faidherbe’s statue after strong gusts of wind toppled it from its pedestal in September 2017. This episode has raised intense debate, with opinions in some cases declaring that this “was the perfect opportunity to get rid of it once and for all” and others arguing that Faidherbe was “the creator of modern Senegal and the liberator of black Senegalese facing the exactions of the Moors.”Footnote 8

Achille Mbembe’s “conspiratorial reading of history” (Reference Mbembe2001:11), identifying Africa’s need to annihilate its enemy (the colonizer) as a common model for producing cultural identity, is also useful here, particularly if we focus on the recent actions promoted by the Mauritanian government. While reflecting on Mbembe’s views, what is probably more surprising are the difficulties observed in the process of structuring national identity, almost sixty years after the closure of the colonial moment in Mauritania. If the memory/resistance debate in Mauritania in fact portrays the colonizer as an enemy—despite the depth of the social, political, and economic bonds still noticeable between Nouakchott and Paris—it equally resonates with more profound social questionings specific to Mauritanian hassanophone spheres.

The most prominent aspect of the resistance debate relates to the reawakening of the well-known rivalry between groups of different status (Hassān and Zwāya). The present reassessment of the country’s history affirms the resuscitation of a unresolved centuries-old quarrel, which was muted during the colonial and immediate postcolonial period. The difficulties faced by Mauritania in its transition from colony to independent state—difficulties also evident in the theorizing efforts of researchers on postcolonial spheres (Seth Reference Seth2014)—are proof of the ubiquitous character of these internal tensions. One wonders if Mauritania is not finally concluding its decolonial transition, through what Mudimbe (Reference Mudimbe1994:xiv) called a return to the “original locality.” Our analysis has broader significance for current debates about the decolonization of knowledge, insofar as the data presented here declare a valuable reassessment of Mauritania’s colonial period (and, in fact, of the overall western region of the Sahara). The succession of long political administrations (Daddah, 1960–1978; Ould Taya, 1984–2005), as well as the instability generated between these regime-change periods, seem to have somewhat frozen the public debate associated with the country’s colonial past. It might have taken Mauritania more than half a century to fully consider its internal tensions and, while coming to terms with its colonial past, reassess the social designs associated with its Bidhan populations.

Society and history in the muqawama debate

In order to fully understand the surge of publications denying the existence of a resistance movement to colonization in Mauritania, it is necessary to briefly recall the region’s underlying sociohistorical context. The population of the Islamic Republic of Mauritania comprises an Arab-Berber community known as Bidhan (Moors in English) and three Black African communities: Pulaar, Soninké, and Wolof. Traditionally, each of these communities hierarchically discriminates between “noble” groups—of “religious” and “warrior” status—served by different tributary populations (Barry Reference Barry1985; Bathily Reference Bathily1989; Kane Reference Kane1986). As the resistance debate dealt with in this article is limited to the Bidhan, we will restrict ourselves to presenting the historical background of this community, which took its current form in the seventeenth century, with the consolidation of the duality between the two components of its nobility: a “religious” group of Sanhadja origin (the Zwāya) and a group of warriors of Arab origin (the Hassān). The Arabs who began their descent into present-day Mauritania in the fifteenth century triumphed over the region’s original inhabitants and later founded supra-tribal political organizations called emirates, four of which reigned over the Moorish country: Trarza, Brakna, Tagant, Adrar.Footnote 9

At the end of the nineteenth century, conflicts between different emirates, and succession crises within one emirate, created an “anarchic” (sayba) milieu, marked by the increase of depredatory raids carried out by the tribes of the north (the Ahil Sahil, essentially comprising the Rgueybat, the Awlād Busba, and the Awlād Dlaym), which frequently targeted the southern (Al-Gibla) Zwāya tribes, who pejoratively called their rival groups lamhaliyyin (“the wicked”).Footnote 10

It is during this period (the late nineteenth century) that the existing rivalries between nomadic groups (from the north) and southern Mauritanian populations (much more attached to commerce and with very limited nomadic routes) started to experience the interference of European colonial powers throughout the extended western Saharan region. French authority, centralized in Saint-Louis (a town bordering Mauritania, on the southern margins of the Senegal River basin), hoped to consolidate its rule over the northern (eminently Saharan) territories. This ambition (Taylor Reference Taylor1995) should be seen in the context of the southern Moroccan frontier, where the Spanish accelerated a colonial project of their own for the western Sahara. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in addition to intra-Saharan social rivalries (often comprising north-south depredatory raids), interventions by colonial actors throughout the entire Bidhan region of influence were increasingly significant.

The Zwāya, suffering from predatory raids from the north and often oppressed by warrior groups from their own emirate (Ould Mohamed Baba Reference Ould Mohamed Baba1984:7), supported the machinations of Xavier Coppolani, a colonial officer who, with the aid of distinguished Zwāya figures such as Cheikh Sidiya Baba, ratified the French protectorate over the Trarza (El Gibla) region (southwestern Mauritania) on December 12, 1902 (Harrison Reference Harrison1988:33–40).Footnote 11

From the Hassān standpoint, opposition to this agreement was immediate. Ahmed Ould Deid, the Trarza emir, now a hero for the resistance party, decided to attack the French forces. The Brakna emir, Ahmedu Ould Sid’Eli, also participated in the 1906 battles against the French. Bakar Ould Swayd Ahmed, the emir of the Tagant, and Sid’Ahmed Ould Ahmed Ould ‘Ayda, the Adrar emir, were both killed in combat (in 1905 and 1932 respectively).

Coppolani was murdered in Tidjikja on May 12, 1905, by a commando unit led by Sharif Sidi Ould Moulay Zein.Footnote 12 In the aftermath, armed groups from different regions, galvanized by the psychological effect of Coppolani’s death and with the support of the Moroccan sultan, created a federation under the banner of Cheikh Ma al-‘Ainin.Footnote 13 The French forces subsequently suffered a number of crushing defeats, forcing them to deploy many more troops to maintain control of the Adrar region (northern Mauritania) in 1909 (Bonte Reference Bonte1984, Reference Bonte2006). By then, the northern tribes, often called tlāmīd (“disciples”) of Cheikh Ma al-‘Ainin, and commanded by Ma al-‘Ainin’s own sons, were raiding colonial military posts while also attacking the populations of the Al-Gibla region, whom they accused of providing logistical support to colonial forces. The followers and sons of Cheikh Ma al-‘Ainin justified these actions by a fatwa, which declared that the goods owned by these populations constituted lawful booty.Footnote 14 These guerrilla raids continued until 1934, when aviation and radio TSF started to operate in Mauritania.Footnote 15 In the same year, a joint colonial operation, uniting troops from Sudan (colonial Mali), Algeria, and Morocco, regrouped around Mauritania’s northeastern borders. This blocked off the corridors from which the groups of fighters staged their attacks on French military posts. This is the historical context that led to the “war of memories” currently taking place in Mauritania.

“You are nothing but looters”

Since at least November 28, 2008, the commemorations of Mauritania’s independence have been permanently marked by controversy. While declaring their right to freedom of expression, some speakers have started openly to attack Zwāya status groups (those from the Trarza/Al-Gibla region, in particular), who are regarded as the main endogenous vectors of colonial occupation and openly treated as “traitors to the national cause.” They have been accused of responsibility for facilitating colonization, “by offering them [the colonizers] legitimacy through treaties and fatwas and by providing them with supplies.”Footnote 16 In contrast, according to this view, the Hassān established a coherent front blocking French occupation.

Faced with these attacks, the voices of those opposed to the existence of any resistance movement in Mauritania also gained an audience in the general public, and over time the media began to give them a lot of publicity. An online article with the corrosive title “National Resistance: Myth or Reality?” was published in 2014. The author of this article described the muqawama as “a war of interests, of raids and counter-raids of looter gangs” (Ould Inalla Reference Ould Inalla2014).

One of the authors spurring the greatest controversy was undoubtedly Omar Ould Beibacar.Footnote 17 Ould Beibacar published a series of articles about the “resistance,” the first of which was in response to the decision to name Nouakchott’s new airport “Um Tounsi.”Footnote 18 He called for this decision to be reversed, claiming it was intended only to “immortalize a battle in which several dozen Mauritanian soldiers from the Trarza Nomadic Group were massacred in an ambush by a ghazi of 120 foreign looters.”Footnote 19 In his rendition, this battle was motivated “essentially by a vendetta against Trarza warriors.” He concluded by asking, “how can we honor foreigners who have distinguished themselves by the looting and the systematic slaughter of our fellow citizens?” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015a).

After this first article, Ould Beibacar became more and more virulent, and in his second article titled “Facing Colonial Occupation: Can We Speak of Resistance?” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b), he explicitly attacked the iconic figure of the resistance narrative, Sharif Sidi Ould Moulay Zein (see footnote 12), who, on May 12, 1905, in Tidjikja in central Mauritania, killed Xavier Coppolani, the Governor-General’s delegate and architect of the so-called penetration pacifique (or peaceful expansion) in Mauritania.

Coppolani’s death constitutes a major turning point in Mauritanian colonial history. After his passing, colonial authorities experienced a period of uncertainty, and consideration was even given to withdrawing from Mauritania entirely. The disappearance of the head of the colonial expedition completely disorganized the “Tagant Mission,” which was besieged for a time after being apparently lost in enemy territory far from its bases. (Désiré-Vuillemin Reference Désiré-Vuillemin1999:145–84). On the other hand, news of Coppolani’s death, while giving hope of a definitive end to the colonial expansion, presented additional arguments to the Saint-Louis trading lobby, which had initially opposed Coppolani’s presence in Mauritania and pleaded for France to withdraw after this incident. For the Saint-Louis merchants, it would have been more profitable to continue trading peacefully with the Saharan populations rather than penetrating into their territory. Coppolani’s assassination also boosted the morale of the muqawama partisans, who, by then, were benefiting from the military and organizational support of Cheikh Ma al-‘Aynin. This period, in fact, marked one of the greatest offensives of the resistance, notably with the battles of Tidjikja and N’yimlān in 1906 (Bonte Reference Bonte2002).

Let us now return to Ould Beibacar’s argument as outlined in his second article (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b). He started by minimizing the effective role of the Sharif, suggesting that credit for the operation that made him famous should be shared with Sidi Ould Boubeit, a man the Sharif had met by chance and who nonetheless provided him with information on the precise location and routines of Coppolani and his entourage. According to Ould Beibacar, it was because of this man that the Sharif acquired the information necessary for the success of the operation:

He had given him the precise situation with regard to the internal and external security features of the barracks, the enrolments, and the number of shifts during the day and night, the kind of armaments used, as well as the positioning of the units and the distribution of the missions. He had told him the most secure route to access the camp and set the perfect time and the most favorable place to make the assault, and finally the exact location of Coppolani. (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b)

In addition to noting the amateurish planning of this operation, dependent on the hazardous meeting of an anonymous informant, Ould Beibacar questions the authorship of the founding act of the so-called “Mauritanian resistance,” by asking “Who killed Coppolani?” He quotes Frèrejean, another decisive colonial actor, as saying that “it was a second shot fired by another member of the Sharif group that finished Coppolani off,” and concludes that “the Sharif was not the real killer” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b).Footnote 20 This statement openly confronts a pivotal moment in the building of the resistance narrative. Sharif Sidi Ould Moulay Zein, the martyr par excellence, as well as his defining act of “bravery” are irreverently labeled “le coup de main de Tidjigja” by Ould Beibacar (Reference Ould Beibacar2015b).

Ould Beibacar represents the core argument of those who refuse to qualify the armed actions undertaken against the French during the colonial era as effective acts of resistance. For those who share this opinion, it is the culture of violence and the spirit of plunder that determined these actions, rather than any religious or patriotic motives, as supporters of the resistance narrative claim. According to his interpretation, the muqawama was nothing more than an armed “feudal” fight against French expansion, orchestrated by secular and bloodthirsty emirate leaderships that had profited from such methods since the eighteenth century. Some of the members of this coalition were allied with ambitious militant Sufi brotherhoods whose aim was essentially to preserve a long-established order (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b).

According to Ould Beibacar, the regional status quo was characterized by violence, arbitrariness, and the decline of Islamic values. He argued that the political structures behind these operations (the emirates) lived essentially off the profits earned from the trade in gum arabic, salt, and especially slaves (captured among the black populations of the Senegal River basin), through a systematic plunder of the weakest. For him, the colonial occupation of Mauritania could not have favored the well-established “predation economy” on which certain segments of society based their supremacy. Therefore, in addition to denying the existence of real patriotic and religious motives, the deniers of the muqawama also act as the voice of the groups subjected to the oppression of the “old system,” and who were, naturally, appreciative of the “benefits of colonization” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015b).

Ould Beibacar rejoices at the defeat of what he calls “feudal entities,” which were “fortunately beaten, pacified, and subjected to French colonization, which was much more merciful.” In a highly provocative tone, he titles one of his texts “Merci Coppolani” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015c).Footnote 21 He again heaps criticism on the hero of the resistance, Sharif Sidi Ould Moulay Zein, considering him “an enlightened fanatic” who committed a “heinous crime.” On the other hand, he laments the fate reserved for Coppolani: “an illustrious administrator, a great humanist of superior intelligence, who wanted to make our country the largest and richest of the states of French West Africa” (Ould Beibacar Reference Ould Beibacar2015c).

It is this opposition between the model established by the colonizer and a state of disruption (al-sayba, “the reign of anarchy”) that constitutes the backbone of the arguments of those refuting the muqawama, which is presented as an apologia for arbitrariness.

“You are nothing but ignorant”

The arguments advanced by Ould Beibacar have also been addressed by Ould Haroun, who, in a series of online articles, has distanced himself from the provocative style of Ould Beibacar.Footnote 22 However, Ould Haroun’s arguments can easily be qualified as a pro domo plea. Its author, a lawyer and counselor at the Ministry of Justice, is in fact the grandson of Cheikh Sidiya Baba, and his public intervention was based on what he considered “his family’s moral duty” to defend his ancestor (a renowned Islamic scholar and Brotherhood leader; see footnote 11).

In an introduction to the debate, Ould Haroun states that he hopes to respond, in particular, to the flow of denigrating arguments that became almost intolerable when “November zealots” and provokers, taking advantage of competition among television channels, began to label those who had cooperated with the colonizer as mercenaries, accomplices, lackeys, and traitors (Ould Haroun Reference Ould Haroun2014).Footnote 23 In his response to these “provocations,” he extensively reviews local historiographic accounts and Islamic jurisprudence, to conclude that, due to the local and international geopolitical context, cooperation with the colonizer was the more justifiable option (Ould Haroun Reference Ould Haroun2014).

He repeats Ould Beibacar’s argument, signaling the state of endemic anarchy that reigned in precolonial Mauritania, drawing on the existing sociocultural environment at the time of Cheikh Baba Ould Cheikh Sidiya. He defends his ancestor’s doctrinal position and reformist project, based on that of his grandfather, Cheikh Sidiya Ould Mokhtar al-Hayba (1777–1868) (Robinson Reference Robinson2001:178–93).Footnote 24

The elements of Islamic jurisprudence evoked by Ould Haroun remove all legitimacy from jihad/“resistance.” The basic conditions for jihad—the appointment of an imam and the establishment of communal funds—were simply not met in colonial Mauritania. For Ould Haroun, jihad is prescribed only when the hostility of the Christian party prevents Muslims from practicing their rite—something that, in his opinion, did not occur in colonial Mauritania (Ould Haroun Reference Ould Haroun2014).

Ould Haroun also observed the geopolitical arguments explored in a fatwa by Cheikh Sidiya, where he argued for a peace pact with the French. His argumentation was based both on legal/theological justifications as well as on a pragmatic/political basis, as he viewed colonial progression as an unavoidable reality acknowledged all over the world. He thus concluded that it was better to negotiate peace with the French before being confronted with their—inevitable—occupation of Mauritania (Ould Haroun Reference Ould Haroun2014).

The theological controversy, according to Ould Haroun, revolved around the writings of Islamic scholars who had allowed their followers to plunder the goods of the populations subjected to, or who were accomplices with, the French.Footnote 25 On the basis of the evidence available to him, he demonstrates that these scholars finally distanced themselves from their initial position and prohibited any harm to the lives and property of the populations of southwestern Mauritania (Ould Haroun Reference Ould Haroun2014).Footnote 26 The absence of legal (Islamic) foundations for a resistance movement, the inevitability of colonization, and the anarchic antecedent acknowledged in the region supports the position of the muqawama deniers. These arguments should suffice to justify their cooperation with the colonial authority. The logical conclusion to this argument emphasizes the unfounded nature of the “resistance” and the pure and simple denial of the existence of such a movement.

Political uses of the muqawama

The Mauritanian government was itself directly involved in debates around the muqawama, and one might even speculate that it had a role in the creation of the controversy. Indeed, it was after a presidential speech, delivered in November 2009, during the official celebrations to mark the country’s independence, that laudatory interventions regarding the resistance started to permeate the media landscape. In his speech, President Aziz declared:

Our people have undeniably proved their commitment to these values through the enormous sacrifices they have made, with bravery and nobility, during the colonial period. Therefore, this anniversary is, for us, an opportunity to remember the martyrs of the motherland (Shuhada al-watan) in all pride and the heroes of the resistance that Allah has immortalized by His holy words.Footnote 27

One might regard this moment as the start of the official rehabilitation of the resistance narrative in Mauritania, through a political effort expressed by the country’s highest figure. In celebrating the heroism of “the resistance” and meditating on its martyrs, President Aziz committed the state to a policy that defends the need to rewrite the country’s recent history, thus questioning a historiographic tradition in which resistance to colonialism had, to a very large extent, been officially silenced.Footnote 28

In stark contrast to the first generation of Mauritanian political leaders, President Aziz declared the emergence of a “New Mauritania,” which should distance itself from the “old regimes.” In his view, resistance should play a pivotal role in this agenda. Aziz’s role as champion of the resistance was made clear in yet another statement, made in November 2016, when he declared that “Mauritania has a rich history of fighting against colonialism… . The nonwriting of the history of the national resistance is explained by external and internal causes, but it is necessary to write this history and to value it.”Footnote 29 It is evident that the internal reasons he refers to are associated with the political class that governed the country until 1978, which blatantly rejected the resistance topos. These political actors have been portrayed as direct heirs of the Gibla (southwestern Mauritania) politico-religious elite that established peace with the French colonial forces and continued to play a decisive role in the country’s transition to independence. For those in the resistance camp, the Gibla political actors have always aimed to silence anything likely to shame French colonization of Mauritania.

More recently, the resistance controversy has moved into Mauritania’s parliament, confirming its appropriation by eminently political groups. Following days of consultations, which were boycotted by some members of the opposition, revisions to the 1991 constitution were put to a referendum. The proposed amendments included changes to two key symbols associated with the first civil regime: the flag and the national anthem.Footnote 30 Concerning the flag, it was proposed that two red stripes be added to the original design, symbolizing the blood of the martyrs of the resistance (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The current Mauritanian flag now incorporates 2 red stripes, symbolizing the blood of the martyrs of the resistance

As for the national anthem, the suggestion was made to introduce a completely new theme. For those proposing this amendment, the national anthem did not display any elements likely to stimulate patriotic fervor, and, probably more importantly, it made no reference to the resistance. Those opposed to this proposal reiterated that the religious character of the hymn was the best conceivable formula for uniting the entire country around the song.Footnote 31

The debate leading to the parliamentary approval of a new flag and a new national anthem perfectly illustrates the socio-political poles characterizing the current resistance debate in Mauritania. For those unwilling to accept changes to these national symbols, Mauritania’s first civil regime represented a blessed time of affirmation of national identity, of civic values, and of economic development. For those defending the amendments, Aziz’s efforts were valued as patriotic acts, in line with the president’s courageous reformist policies.

At times, this debate also assumed a regionalist angle, and was dragged into vulgarity and quibble in the antagonism between “the people of the north” and “the people of the south” (Ould Eida Reference Ould Eida2015). It was ultimately a controversy between the opposition, which sometimes used the arguments of the resistance deniers, and the supporters of President Aziz, who always supported the resistance and therefore supported the proposed reforms. The constitutional amendments finally adopted express the alignment between the government and those glorifying the resistance.Footnote 32

These changes to the flag and the anthem, in addition to the renaming of Nouakchott Airport (now “Oumtounsy International Airport,” see Figure 5), can be likened to “memorial laws,” in that the state legislates on the basis of a non-consensual representation of the country’s past.Footnote 33

Figure 5. The new Nouakchott international airport, named after the battle of Um Tounsi (Photo by Elemine Ould Mohamed Baba)

Conclusion

The current memory debate in the Islamic Republic of Mauritania is inextricably linked to the country’s colonial past. But it also sheds light on the complexity of the region’s social design, associated in particular with its Bidhan populations. The government’s clear stance in this debate has helped to amplify the voices denying the existence of any structured resistance to the French colonial powers, leading to a dangerous bipolarization between north and south in the country. From the political perspective, this “war of memories” represents a standoff between the old political regime and President Aziz’s project of a “new Mauritania.” The new generation of political actors brought about a different interpretation of the past, and the Mauritanian political elite of the 1960s and 1970s is heavily criticized for the role it played during the colonial period. Despite the strong presence of a political component, it would be a mistake to interpret this debate solely through a political lens. This debate also touches on the division between Zwāya and Hassān social status groups. The former were the main figures in the country’s political landscape during the transition period from independence to regime change in 1978, while the latter, favoring Hassān values, are currently finding themselves emboldened by former President Aziz’s policies and those of his designated successor.

Will the government persevere in its commitment to the “war of memories” by continuing to promulgate memorial laws? Will it recognize the rights of the resistance fighters and perhaps even support their reparation? And will it consider a gesture toward the frustrated Negro-African and Haratine communities, who claim recognition of past injustices? The rewriting of history that the Mauritanian government has more recently tried to accomplish would necessarily need to involve historians in the process. The absence of any state initiative in this direction would validate government actors limiting themselves to a mere instrumentalization of memories. Contrary to the debate in France, where historians have voiced their disapproval of the state’s “abuse of memory” (Berliner Reference Berliner2005), Mauritanian historians have not (yet) intervened in this controversy, leaving the stage open for amateurs and polemists on both sides.

The muqawama debate examined here might also be conceived of as the closure of the colonial period in Mauritania, epitomized by France’s “peaceful expansion” and its proposed model of “development” (Sarr Reference Sarr2016:26). In this regard, an effective return to local spheres of debate and influence, which largely coincides with the social model acknowledged in the western regions of the Sahara, is clearly noticeable (Bonte Reference Bonte1984:28). But if this is indeed the case, the Hassān/Zwāya partition is not the only subject in need of re-evaluation; we must also reconsider the contemporary prominence, and intricate role, attached to other actors with stigmatized genealogies, who have also begun to make their voices heard in the country’s social landscape.

Acknowledgments

This study has benefited from the comments provided by the African Studies Review editorial team, and for the critical inputs made by Saad Bouh Ould Mohamed Moustapha, Ahmed Ould Haroun, Abdoulaye Diakhité, José da Silva Horta and Carlos Almeida.

This article is part of a project that has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 716467)