Refine search

Actions for selected content:

15366 results in Military history

Index

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 352-360

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Colonial Warfare: Case Studies

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 76-128

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Maps

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp vii-vii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Abbreviations

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp xii-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Contents

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp v-vi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Colonial Warfare

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 38-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Transimperial Knowledge

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 129-187

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

A Note on Language

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp xi-xi

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

References

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 315-351

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- The Colonial Way of War

- Published online:

- 04 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

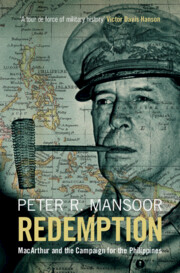

Redemption

- MacArthur and the Campaign for the Philippines

-

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025

10 - The Central and Southern Philippines

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 391-417

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Soldiers

-

- Book:

- Making Antifascist War

- Published online:

- 28 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 64-91

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Wars of dynasties, wars of empires: The nature of European conflicts, 1648–1792

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of War

- Published online:

- 18 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 309-341

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - The Battle for Leyte

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 221-269

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

- from Part III - The Downfall

-

- Book:

- The Generalissimo

- Published online:

- 31 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 229-234

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Copyright page

-

- Book:

- Making Antifascist War

- Published online:

- 28 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp iv-iv

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - ‘That most imperfect military organization’

- from Part I - The Ascent

-

- Book:

- The Generalissimo

- Published online:

- 31 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 43-65

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Leyte Gulf

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 174-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Real Thing

- from Part II - The Enigma of Consensus

-

- Book:

- The Generalissimo

- Published online:

- 31 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 111-137

-

- Chapter

- Export citation