Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

Foreword

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Maps

- Introduction

- 1 A bed of his own blood: Nombuyiselo Ntlane

- 2 This country is my home: Azam Khan

- 3 On patrol in the dark city: Ntombi Theys

- 4 Johannesburg hustle: Lucas Machel

- 5 Don't. Expose. Yourself: Papi Thetele

- 6 The big man of Hosaena: Estifanos Worku Abeto

- 7 Do we owe them just because they helped us?

- 8 Love in the time of xenophobia: Chichi Ngozi

- 9 This land is our land: Lufuno Gogoro

- 10 Alien: Esther Khumalo*

- 11 One day is one day: Alphonse Nahimana*

- 12 I won't abandon Jeppe: Charalabos (Harry) Koulaxizis

- 13 The induna: Manyathela Mvelase

- Timeline

- Glossary

- Selected place names

- Contributors

Summary

I have a deep, personal connection with migration. My parents met in Bloemfontein during apartheid. They were from a different province, migrant workers living as ‘foreigners’ in the Free State, given the influx control laws of the time. Soon after I was born, our small family moved to Mmabatho, in the bantustan state of Bophuthatswana. In 1988, when I was seven, political strife forced us to flee to Botswana. During the process of moving, my father, sister and grandmother nearly died in a car accident that took place under mysterious circumstances, so we continued to live with fear and insecurity. My father wouldn't say why, but it had to do with Lucas Mangope, the president of Bophuthatswana. The Anglican Church ended up giving my father a job and providing comfortable shelter and school for my sister and me in Botswana. My parents always told us that one day, we would go back home to South Africa.

When my baby sister and I started at our new school, it wasn't easy to explain where exactly we came from. For her, it didn't really matter because five-year-olds have little awareness of such things and adapt easily. I, however, was still traumatised by the car accident and, although I was little, I knew exactly what was going on. I also knew it was not likely that I would ever see my friends and old teachers again. It's bad enough being the new kid in school, but having a weird back story makes you stick out even more. Eventually I found my way; my school had children from all over the world, and the South African community in Gaborone was closely involved with the Anglican Church, which played a significant role in the anti-apartheid movement. Looking back, I am grateful that I had a strong, caring community to buffer me from the sense of alienation that typifies the experiences of many migrants across Africa. Also, my family remained intact and we were comforted and fortified by the love and protection of our parents.

During quiet time at home, my parents would tell us stories about South Africa, insisting that we came from a country of brave and talented people, and it was to South Africa that we belonged.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

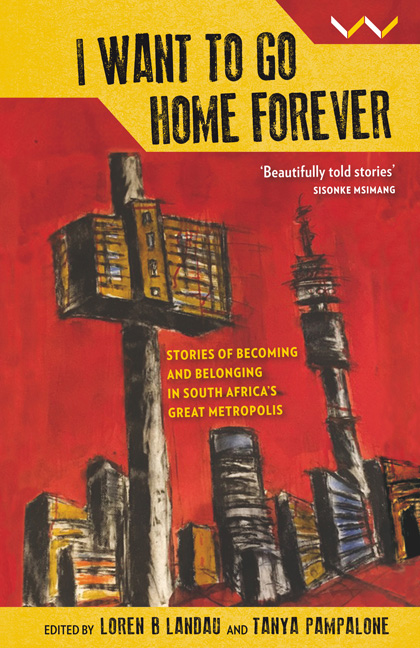

- I Want to Go Home ForeverStories of Becoming and Belonging in South Africa's Great Metropolis, pp. xi - xviPublisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2018