Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

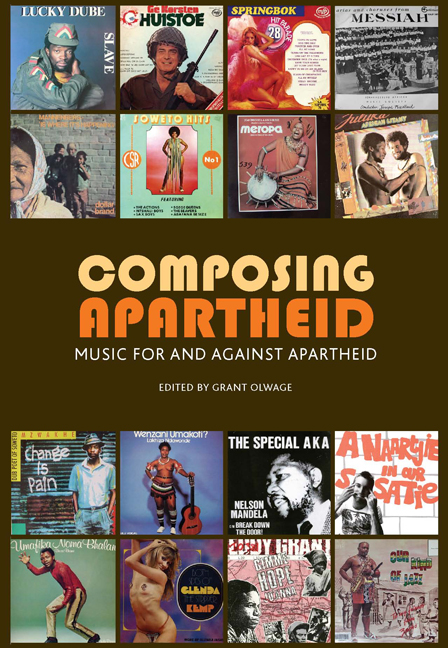

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Chapter 10 - Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 April 2018

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Back to the Future? Idioms of ‘displaced time’ in South African composition

- Chapter 2 Apartheid's Musical Signs: Reflections on black choralism, modernity and race-ethnicity in the segregation era

- Chapter 3 Discomposing Apartheid's Story: Who owns Handel?

- Chapter 4 Kwela's White Audiences: The politics of pleasure and identification in the early apartheid period

- Chapter 5 Popular Music and Negotiating Whiteness in Apartheid South Africa

- Chapter 6 Packaging Desires: Album covers and the presentation of apartheid

- Chapter 7 Musical Echoes: Composing a past in/for South African jazz

- Chapter 8 Singing Against Apartheid: ANC cultural groups and the international anti-apartheid struggle

- Chapter 9 ‘Nkosi Sikelel' iAfrika’: Stories of an African anthem

- Chapter 10 Whose ‘White Man Sleeps’ Aesthetics? and politics in the early work of Kevin Volans

- Chapter 11 State of Contention: Recomposing apartheid at Pretoria's State Theatre, 1990–1994. A personal recollection

- Chapter 12 Decomposing Apartheid: Things come together

- Chapter 13 Arnold van Wyk's Hands

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

Introduction

In the late 1970s and 1980s, when apartheid still held sway in South Africa, the composer Kevin Volans wrote a set of compositions entitled African Paraphrases. Though they were cast in a Western idiom, these works drew on distinctly African modes of music-making, such as music of the mbira dza vadzimu and matepe from Zimbabwe, lesiba music from Lesotho and nyanga panpipe music from Mozambique, to name a few representative instances. Volans’ paraphrase compositions, which gained considerable success in Europe and America, posed a conspicuous challenge to the ‘official’ aesthetic ideology of apartheid in South Africa. In his various statements and writings Volans has addressed his musical compositions to predicaments across two intersecting political arenas: On the one hand, he argues that his early music was meant to effect ‘reconciliation’ between ‘African and European aesthetics’ (through connecting what was deemed culturally separate). On a local level, then, the composer regards the music as his ‘small contribution to the struggle against apartheid’ (Volans, n.d.). On the other hand, Volans’ early music was meant to call into question the industrialised standardisation of Western culture in general; its obsession with (what the composer calls) an ‘objectified and reified’ sound that ultimately would end ‘in a nightmare of alienation’ (Volans, 1986). On a general level, that is, the composer argues that the processes of capitalist modernisation have had a largely negative impact on African music, seeking either to domesticate it (‘to Westernise African music’); or to exoticise it (give it ‘local colour’). Instead, Volans sought to ‘gently set up an African colonisation of Western music and instruments’ as if to ‘introduce a computer virus into the heart of Western contemporary music’ (Volans, n.d.). The principal mechanism used to achieve this reversal in his early works was quotation and, of course, paraphrase.

This article examines the hoped-for politics implied by the ways Volans’ paraphrase technique allows one cultural practice to intersect and blend with another in a time of rigid cultural divisions. By borrowing some (and warding off other) African musical forms and intensities, and thereby effectively moving a carefully chosen selection of African fragments of musical text (transcriptions and performance techniques) from one place to another, Volans’ early music offers a unique critical glimpse into the complex social processes through which musical rituals in various quarters were, and are, routinely understood.

Information

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Composing ApartheidMusic for and against apartheid, pp. 209 - 236Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2008