Refine search

Actions for selected content:

102 results

Chapter 2 - Darwin’s Predecessors

-

- Book:

- Darwin's Philosophy of Emotion

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 34-60

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - “All the Logic I think Proper to Employ”

-

-

- Book:

- Hume's <i>A Treatise of Human Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 05 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 64-78

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Scientific Ethos of Modern China: A Genealogy of Seeking Truth from Facts

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Chinese History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 December 2025, pp. 1-26

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - What This Book Is About

- from Part I - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Genes, Brains, Evolution and Language

- Published online:

- 13 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 November 2025, pp 3-16

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Romance as a Method, Enjoyment as Empiricism

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Public Humanities / Volume 1 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 October 2025, e150

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Empiricism and Kantian Accounts of Thought Experiment

- from Part I - The Origins of “Thought Experiment” in Kant and Ørsted

-

- Book:

- Kierkegaard and the Structure of Imagination

- Published online:

- 26 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 16 October 2025, pp 63-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Cognitive Development, Modularity and Innateness

-

- Book:

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Published online:

- 30 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025, pp 117-140

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Aquinas, Perception, and the Question of Realism

-

- Journal:

- New Blackfriars ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 October 2025, pp. 1-18

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Theology as social knowledge

-

- Journal:

- Religious Studies / Volume 61 / Issue S2 / December 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 September 2025, pp. S173-S190

- Print publication:

- December 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

6 - Eradicating Ethos

- from Part III - Façade of Neutrality

-

-

- Book:

- Rhetorical Traditions and Contemporary Law

- Published online:

- 02 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 May 2025, pp 119-138

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - Logical Empiricism

- from Part I - Background and Basic Concepts

-

- Book:

- An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science

- Published online:

- 29 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 March 2025, pp 39-50

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - An Empire of Experts

-

- Book:

- Global Servants of the Spanish King

- Published online:

- 20 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 27 February 2025, pp 128-165

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Continental Naturalism

- from Part IV - Writing as Vivisection

-

- Book:

- Vivisection and Late-Victorian Literary Culture

- Published online:

- 30 January 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 February 2025, pp 185-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Language and Style

-

- Book:

- Stylistics

- Published online:

- 18 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 1-31

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

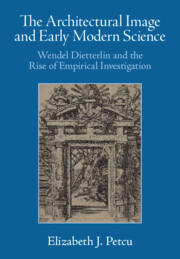

Two - Devising the Architectura: Rationalism and Empiricism in Architectural Design

-

- Book:

- The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science

- Published online:

- 29 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024, pp 103-168

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Naturphilosophie and the Problem of Clean Hands

- from Part I - Hegel’s Philosophy of Nature in the Historical and Systematic Context

-

-

- Book:

- Hegel's <i>Philosophy of Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 19 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024, pp 58-75

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 13 - The Prospects for an Idealist Natural Philosophy

- from Part IV - On Contemporary Challenges for the Philosophy of Nature

-

-

- Book:

- Hegel's <i>Philosophy of Nature</i>

- Published online:

- 19 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 December 2024, pp 259-272

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The Architectural Image and Early Modern Science

- Wendel Dietterlin and the Rise of Empirical Investigation

-

- Published online:

- 29 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 19 December 2024

1 - The Dream of the Butterfly

- from Part I - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Curating the Enlightenment

- Published online:

- 07 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 07 November 2024, pp 3-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Classic Hedonism Reconsidered

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation