Refine search

Actions for selected content:

310 results

8 - Holding against the Storming

-

- Book:

- Ability and Difference in Early Modern China

- Published online:

- 10 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 September 2025, pp 186-211

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Commerzbank

-

- Book:

- Extroverted Financialisation

- Published online:

- 07 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 21 August 2025, pp 127-142

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Specialist mental health crisis centres in England: a step forward or a stumble in the dark?

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Open / Volume 11 / Issue 5 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 August 2025, e187

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Macroeconomic populism in Chile: Allende and the recession of 1973

-

- Journal:

- Revista de Historia Economica - Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 August 2025, pp. 1-28

-

- Article

- Export citation

2 - Orders in Transition and Implications for Political Legitimacy

- from Part I - Setting the Stage

-

- Book:

- The Law and Politics of International Legitimacy

- Published online:

- 14 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025, pp 24-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Change of International Order and Legitimacy

- from Part V - International Legitimacy and Change

-

- Book:

- The Law and Politics of International Legitimacy

- Published online:

- 14 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 24 July 2025, pp 318-349

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

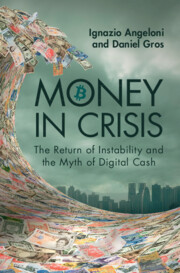

Money In Crisis

- The Return of Instability and the Myth of Digital Cash

-

- Published online:

- 15 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025

Pandemics meet democracy: the footprint of COVID-19 on democratic attitudes

-

- Journal:

- Political Science Research and Methods , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 15 July 2025, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

11 - What Is the Societal Impact of Innovation?

-

- Book:

- Innovation Management

- Published online:

- 06 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025, pp 160-177

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Rapid Communication: The Fate of Global Humanitarian Assistance Amidst Growing Health Challenges

-

- Journal:

- Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness / Volume 19 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 June 2025, e167

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

6 - Dehumanising Refugees

- from Part II - Confronting Global Contradictions

-

- Book:

- Global Crisis and Insecurity

- Published online:

- 01 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 132-153

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - The Existential Unsettling of Security

- from Part II - Confronting Global Contradictions

-

- Book:

- Global Crisis and Insecurity

- Published online:

- 01 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 61-85

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - The Future of Humanity Does Not Look Good

- from Part I - The Dark Energy of Our Time

-

- Book:

- Global Crisis and Insecurity

- Published online:

- 01 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 3-32

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Moving towards a Manifesto

- from Part III - Struggling for Positive Human Development

-

- Book:

- Global Crisis and Insecurity

- Published online:

- 01 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp 279-308

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Preface

-

- Book:

- Money In Crisis

- Published online:

- 15 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 12 June 2025, pp ix-xii

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Democracy through crises: state, regions and the influence of technocracy and expertise in Italy (2008–2020)

-

- Journal:

- Italian Political Science Review / Rivista Italiana di Scienza Politica , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 May 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

‘I would have killed myself had it not been for this service’: qualitative experiences of NHS and third sector crisis care in the UK

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych Open / Volume 11 / Issue 3 / May 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 May 2025, e107

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Myanmar Earthquake Aftermath – Critical Update and Expanded Analysis

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness / Volume 19 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 May 2025, e125

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Global social policy ideas in the COVID-19 crisis: Ideational change and continuity in the ILO, the OECD, the WHO, and the World Bank

-

- Journal:

- Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy / Volume 41 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 April 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

2 - The Great Conflagration (1914–1918)

-

- Book:

- The European Art Market and the First World War

- Published online:

- 10 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 April 2025, pp 66-104

-

- Chapter

- Export citation