Refine search

Actions for selected content:

52 results

7 - Human Rights and One Health

- from Part II - One Health and Contemporary Legal Structures

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of One Health and the Law

- Published online:

- 25 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025, pp 89-103

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Public Health Law

- from Part III - One Health and Future Legal Structures

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of One Health and the Law

- Published online:

- 25 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 09 October 2025, pp 259-271

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Toward a Posthumanist Understanding of Wartime Suffering: Public Concern for Animal Welfare in Ukraine

-

- Journal:

- Perspectives on Politics , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 August 2025, pp. 1-25

-

- Article

- Export citation

Representation of Nature and Animals in Pakistan Primary Textbooks and Reimagining Environmental Education for the New Generations

-

- Journal:

- Australian Journal of Environmental Education / Volume 41 / Issue 4 / September 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 August 2025, pp. 968-984

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - The Ancient World

- from Part I - Historical Periods

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of Literature and Plants

- Published online:

- 06 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 7-22

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Thriving World

-

-

- Book:

- How People Thrive

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 261-287

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

12 - Imag(in)ing Human–Robot Relationships

- from Part II - Social and Moral Issues

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Religion and Artificial Intelligence

- Published online:

- 20 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 201-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - A Degrowth Perspective on Environmental Violence

- from Part II - Critical Engagement of and with Environmental Violence

-

-

- Book:

- Exploring Environmental Violence

- Published online:

- 06 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 May 2024, pp 208-222

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A non-anthropocentric solution to the Fermi paradox

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Astrobiology / Volume 23 / 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 March 2024, e9

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Decentring the human

-

- Book:

- Re-imagining Social Work

- Published online:

- 07 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 30-52

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

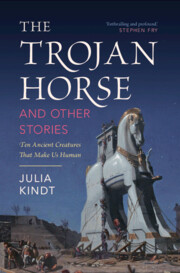

The Trojan Horse and Other Stories

- Ten Ancient Creatures That Make Us Human

-

- Published online:

- 09 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 11 January 2024

19 - Feminist and Queer Theories of the Non/Human and Paradoxical Possibilities of the Slash

- from Part Four - Desires and Relations

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook for the Anthropology of Gender and Sexuality

- Published online:

- 29 September 2023

- Print publication:

- 19 October 2023, pp 520-548

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

16 - The Sublime in American Romanticism

- from Part II - Romantic Sublimes

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to the Romantic Sublime

- Published online:

- 06 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 20 July 2023, pp 207-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - What Is a Good Decision?

-

- Book:

- Decisions for Sustainability

- Published online:

- 25 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 08 June 2023, pp 77-97

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The impacts of environmental science on Bhutanese students’ environmental sustainability competences

-

- Journal:

- Australian Journal of Environmental Education / Volume 39 / Issue 4 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 March 2023, pp. 437-451

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Anthropomorphism and anthropocentrism as influences in the quality of life of companion animals

-

- Journal:

- Animal Welfare / Volume 16 / Issue S1 / May 2007

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 11 January 2023, pp. 149-154

-

- Article

- Export citation

Learning to Live with Strange Error: Beyond Trustworthiness in Artificial Intelligence Ethics

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics / Volume 33 / Issue 3 / July 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 January 2023, pp. 333-345

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Animal ethics and the work of the International Whaling Commission

-

- Journal:

- Animal Welfare / Volume 22 / Issue 1 / February 2013

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2023, pp. 131-132

-

- Article

- Export citation

What do animals want?

-

- Journal:

- Animal Welfare / Volume 28 / Issue 1 / February 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 01 January 2023, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

14 - Ecological Interpretation

- from Part II - Frameworks/Stances

-

-

- Book:

- The New Cambridge Companion to Biblical Interpretation

- Published online:

- 15 October 2022

- Print publication:

- 22 December 2022, pp 265-282

-

- Chapter

- Export citation