Refine search

Actions for selected content:

7 results

5 - The Arrests Begin

- from Part III - Conspiracy Arrested

-

- Book:

- Seditious Spaces

- Published online:

- 06 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 March 2025, pp 141-175

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Seditious Spaces

- Published online:

- 06 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 March 2025, pp 1-20

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

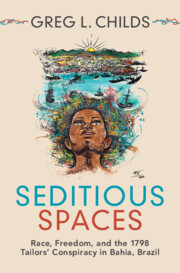

Seditious Spaces

- Race, Freedom, and the 1798 Tailors' Conspiracy in Bahia, Brazil

-

- Published online:

- 06 March 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 March 2025

15 - Costumes

- from Part II - Theater

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 105-112

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

40 - Textiles and Clothing Construction

- from Part IV - Science and Technology

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 288-293

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part IV - Science and Technology

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 247-322

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Part II - Theater

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Guide to the Worlds of Shakespeare

- Published online:

- 17 August 2019

- Print publication:

- 21 January 2016, pp 67-160

-

- Chapter

- Export citation