Refine search

Actions for selected content:

84 results

Improving Constitutional Adjudication in Francophone Africa through Human Rights Treaties and Case Law: the Benin Constitutional Court

-

- Journal:

- Journal of African Law , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 09 September 2025, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Pan-African Print in Interwar Britain: Ras T. Makonnen and International African Opinion

-

- Journal:

- Transactions of the Royal Historical Society , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 August 2025, pp. 1-24

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - Ethiopianism, Redemptive Pan-Africanism, and the African Nation in the Thought of James Aggrey

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 39-86

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Uafrika na Umoja

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 261-292

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 1-38

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

3 - Building the African Nation

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 120-163

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 293-295

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - African Identity and Practical Pan-Africanism among the Women of the African Association

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 189-217

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Competing Nationalisms and Shifting Loyalties

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 218-260

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

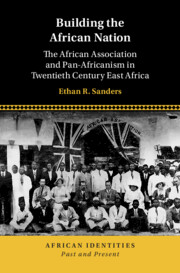

Building the African Nation

- The African Association and Pan-Africanism in Twentieth Century East Africa

-

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025

Chinweizu’s Vision: Unveiling the Complexities of Pan-Africanism and African Sovereignty

-

- Journal:

- African Studies Review / Volume 68 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 February 2025, pp. 111-132

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Multiple Layers of Pan-Africanism and Pan-Ethiopianism in Current Debates on Nationalism and Ethnicity in Ethiopia

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers , FirstView

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 February 2025, pp. 1-16

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

25 - Constitutions and Emerging Federalism

- from Part IV - Nationalism and Independence

-

- Book:

- Understanding Colonial Nigeria

- Published online:

- 21 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 November 2024, pp 530-547

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Music gonna teach: Decolonising IR through a musical exploration of knowledge

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies / Volume 51 / Issue 1 / January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 05 November 2024, pp. 121-138

- Print publication:

- January 2025

-

- Article

- Export citation

Harlem, Addis, and Johannesburg: African Solidarity and African American Internationalism in Harlem from the 1960s to the 1990s

-

- Journal:

- African Studies Review / Volume 67 / Issue 2 / June 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 22 April 2024, pp. 255-294

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

15 - The Essay in the Harlem Renaissance

- from Part II - Voicing the American Experiment (1865–1945)

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of the American Essay

- Published online:

- 28 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 14 December 2023, pp 250-264

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

6 - Towards a Critical Geopolitics of African Military Politics

-

- Book:

- African Military Politics in the Sahel

- Published online:

- 02 November 2023

- Print publication:

- 16 November 2023, pp 169-194

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Tensions on the Railway: West Indians, Colonial Hierarchies, and the Language of Racial Unity in West Africa

-

- Journal:

- The Journal of African History / Volume 64 / Issue 3 / November 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 16 November 2023, pp. 388-405

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Black Power, Raw Soul, and Race in Ghana

-

- Journal:

- African Studies Review / Volume 66 / Issue 4 / December 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 10 August 2023, pp. 988-1012

-

- Article

- Export citation

11 - Pan-African Responses to a Racialized World Economy

- from Part II - Beyond the Three Orthodoxies

-

- Book:

- The Contested World Economy

- Published online:

- 20 April 2023

- Print publication:

- 27 April 2023, pp 187-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation