Refine search

Actions for selected content:

115 results

4 - From Protest to Resistance (1967)

-

- Book:

- Waging Peace

- Published online:

- 03 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 November 2025, pp 119-180

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Nakba: The Displacement of the Medical Community

-

- Book:

- Palestinian Doctors

- Published online:

- 12 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 02 October 2025, pp 214-247

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter Seven - The Afro-Latin American Context

- from Part III - Research Paths: Cuba and Afro-Latin America

-

-

- Book:

- My Own Past

- Published online:

- 30 September 2025

- Print publication:

- 18 September 2025, pp 189-215

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Who Stopped the Equal Rights Amendment?

-

- Journal:

- State Politics & Policy Quarterly ,

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 September 2025, pp. 1-25

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

10 - Civil Society Resistance to Democratic Backsliding

- from Part II - Civil Society, Social Media, and Political Messaging

-

-

- Book:

- Global Challenges to Democracy

- Published online:

- 01 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 15 May 2025, pp 196-214

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - On Manipulation in Politics

- from Part II - The Ethics

-

- Book:

- The Concept and Ethics of Manipulation

- Published online:

- 10 April 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 April 2025, pp 197-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Citizen Advocacy: The Achievements of New Zealand's Peace Activism

-

- Journal:

- Asia-Pacific Journal / Volume 17 / Issue 19 / October 2019

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 March 2025, e2

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

Mobilizing the Rights of Homeless EU Citizens in the Netherlands

-

- Journal:

- German Law Journal / Volume 25 / Issue 6 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 January 2025, pp. 910-918

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

5 - Property

- from Part II - A Tale of Three Cities

-

- Book:

- The Authoritarian Commons

- Published online:

- 21 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 09 January 2025, pp 61-82

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - The End of the German Empire

-

- Book:

- The German Empire, 1871–1918

- Published online:

- 06 December 2024

- Print publication:

- 02 January 2025, pp 546-604

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

“The Anti-Woke Academy”: Dutch Far-Right Politics of Knowledge About Gender

-

- Journal:

- Politics & Gender / Volume 21 / Issue 2 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 December 2024, pp. 195-219

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - War and the State in the Pacific

- from Part III - Case Studies

-

- Book:

- Bringing War Back In

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 185-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - War and the State in Mexico and Central America

- from Part III - Case Studies

-

- Book:

- Bringing War Back In

- Published online:

- 14 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 223-262

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

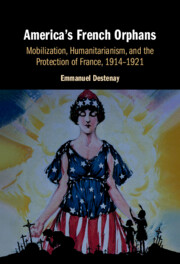

America's French Orphans

- Mobilization, Humanitarianism, and the Protection of France, 1914–1921

-

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024

Discrimination and Political Engagement: A Cross-national Test

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics / Volume 9 / Issue 3 / November 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 October 2024, pp. 472-487

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - Political Participation

- from Part III - The Inputs of Democratic Decision-Making in a Racially Divided America

-

- Book:

- Race and Inequality in American Politics

- Published online:

- 09 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 17 October 2024, pp 216-261

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Ethnopolitics in a Mining Enterprise in Crisis: Revisiting the Albanian Miners’ Protests in Late Socialist Kosovo

-

- Journal:

- Nationalities Papers / Volume 53 / Issue 3 / May 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 August 2024, pp. 600-618

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 26 - Terrorism

- from Part 4 - The new agenda: Globalisation and global challenges

-

-

- Book:

- An Introduction to International Relations

- Published online:

- 31 August 2024

- Print publication:

- 12 August 2024, pp 345-357

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- America's French Orphans

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024, pp 1-17

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - Mobilizing Support for France’s Fatherless Children

-

- Book:

- America's French Orphans

- Published online:

- 24 October 2024

- Print publication:

- 13 June 2024, pp 48-84

-

- Chapter

- Export citation