Refine search

Actions for selected content:

6 results

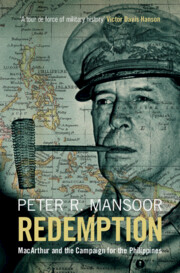

Redemption

- MacArthur and the Campaign for the Philippines

-

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025

5 - Leyte Gulf

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 174-220

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Decision

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 147-173

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

1 - Catastrophe

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 1-50

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

11 - Rebirth

-

- Book:

- Redemption

- Published online:

- 14 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 418-436

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Was There a Diplomatic Alternative? The Atomic Bombing and Japan's Surrender

-

- Journal:

- Asia-Pacific Journal / Volume 19 / Issue 20 / October 2021

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 March 2025, e4

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation