Refine search

Actions for selected content:

59 results

Iron status of Māori, Pacific and other infants in Aotearoa New Zealand

-

- Journal:

- Proceedings of the Nutrition Society / Volume 84 / Issue OCE2 / June 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 July 2025, E161

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Export citation

Indigenous Representational Choices: Results from a Large Qualitative Survey on Māori Electoral Roll Choice

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Race, Ethnicity and Politics / Volume 10 / Issue 2 / July 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 March 2025, pp. 290-311

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Tuning in to the prosody of a novel language is easier without orthography

-

- Journal:

- Bilingualism: Language and Cognition , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 04 February 2025, pp. 1-10

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Indigenous political theory, metaphysical revolt, and the decolonial rearticulation of political ordering

-

- Journal:

- International Theory / Volume 17 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 January 2025, pp. 92-117

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Hauora: relational wellbeing of Māori community support workers

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- The Economic and Labour Relations Review / Volume 36 / Issue 1 / March 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 January 2025, pp. 28-45

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

‘Sovereignty is still the name of the game’: Indigenous theorising and strategic entanglement in Māori political discourses

-

- Journal:

- Review of International Studies / Volume 51 / Issue 1 / January 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 21 February 2024, pp. 22-41

- Print publication:

- January 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Te Kete Aronui

-

-

- Book:

- Learning to Lead in Early Childhood Education

- Published online:

- 17 August 2023

- Print publication:

- 31 August 2023, pp 34-52

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - Assisted Reproduction and Making Kin Connections between Māori and Pākehā in Aotearoa New Zealand

- from Part II - Children’s and Adults’ Lived Experiences in Diverse Donor-Linked Families

-

-

- Book:

- Donor-Linked Families in the Digital Age

- Published online:

- 13 July 2023

- Print publication:

- 27 July 2023, pp 174-191

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Morphological segmentations of Non-Māori Speaking New Zealanders match proficient speakers

-

- Journal:

- Bilingualism: Language and Cognition / Volume 27 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 June 2023, pp. 1-15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

3 - Tactics on Stage: Indigenous Performers, Cultural Exchange and Negotiated Power

-

- Book:

- Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World

- Published online:

- 18 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2023, pp 80-106

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Popular Science in a Changing Māori World

-

- Book:

- Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World

- Published online:

- 18 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2023, pp 168-179

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Pacific Islander Mobilities from Colonial Incursions to the Present

- from Part II - Empires, New Nations, and Mobilities

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Global Migrations

- Published online:

- 12 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2023, pp 123-138

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

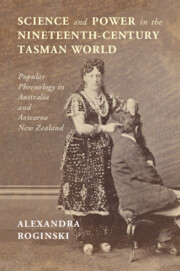

Science and Power in the Nineteenth-Century Tasman World

- Popular Phrenology in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand

-

- Published online:

- 18 May 2023

- Print publication:

- 01 June 2023

2 - A Very British Genocide

- from Part I - Settler Colonialism

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge World History of Genocide

- Published online:

- 23 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 04 May 2023, pp 46-68

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Inequities in COVID-19 Omicron infections and hospitalisations for Māori and Pacific people in Te Manawa Taki Midland region, New Zealand

-

- Journal:

- Epidemiology & Infection / Volume 151 / 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 April 2023, e74

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

A partnership between Māori healing and psychiatry in Aotearoa New Zealand

-

- Journal:

- BJPsych International / Volume 20 / Issue 2 / May 2023

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 27 February 2023, pp. 31-33

- Print publication:

- May 2023

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

9 - Ethnic Change among the Māori in New Zealand

-

- Book:

- Industrialization and Assimilation

- Published online:

- 18 November 2022

- Print publication:

- 22 December 2022, pp 186-211

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

17 - Language, Identity and Empowerment in Endangered Language Contexts

- from Part III - Multilingual Identity and Investment

-

-

- Book:

- Multilingualism and Identity

- Published online:

- 22 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 04 August 2022, pp 341-364

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Indigenous entrepreneurial ecosystems: a comparison of Mapuche entrepreneurship in Chile and Māori entrepreneurship in Aotearoa New Zealand

-

- Journal:

- Journal of Management & Organization / Volume 30 / Issue 1 / January 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 02 May 2022, pp. 40-58

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

14 - Indigenous Rights: New Zealand

- from V - Rights

-

-

- Book:

- Constitutionalism in Context

- Published online:

- 17 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 17 February 2022, pp 303-329

-

- Chapter

- Export citation