Refine search

Actions for selected content:

43 results

Chapter 6 - Counterinsurgency

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 147-172

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 198-201

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - Combat

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 120-146

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 2 - The Australian Army in South Africa

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 35-71

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - Raising Australia’s Army

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 10-34

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 3 - Command

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 72-96

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 1-9

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Morale

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 97-119

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 7 - Coercion

-

- Book:

- Soldiers and Bushmen

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025, pp 173-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

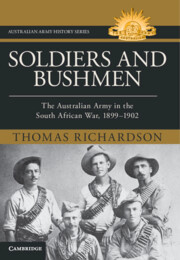

Soldiers and Bushmen

- The Australian Army in South Africa, 1899–1902

-

- Published online:

- 29 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 06 August 2025

Chapter 3 - Preserving scratch

- from Part 2 - Mobilising resources for war

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 50-70

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 4 - Industrial mobilisation

- from Part 2 - Mobilising resources for war

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 71-93

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Introduction

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 15 - The Kangaroo Exercise Series, 1989–1995

- from Part 6 - Deployment challenges

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 320-343

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 8 - Concurrency pressures of accelerated warfare

- from Part 4 - Alliance and concurrency pressures

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 170-176

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 1 - The Australian Army, mobilisation and its recent intellectual history

- from Part 1 - Mobilising an army

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 12-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 14 - Reserve mobilisation for domestic contingencies

- from Part 5 - Force preparation

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 297-318

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 18 - Where to from here?

- from Part 7 - Reflections

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 388-400

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 5 - A double-edged sword

- from Part 2 - Mobilising resources for war

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 94-122

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 10 - The Australian Army’s growing concurrency pressures, 2003–2010

- from Part 4 - Alliance and concurrency pressures

-

-

- Book:

- Mobilising the Australian Army

- Published online:

- 23 May 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 May 2025, pp 201-224

-

- Chapter

- Export citation