Refine search

Actions for selected content:

271 results

8 - Anthropocene

-

- Book:

- Quaternary Climate Dynamics

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026, pp 202-228

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Epilogue

- from Part III - Ripples

-

- Book:

- Violent Waters

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 08 January 2026, pp 313-327

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Quaternary Climate Dynamics

- Integrating Paleoclimate Data, Modeling and Theory

-

- Published online:

- 17 December 2025

- Print publication:

- 22 January 2026

Chapter 6 - Global Warming and Artificial Intelligence

-

- Book:

- Entanglements in World Politics

- Published online:

- 27 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 222-271

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

43 - The Earth Has Been Done

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge History of Australian Poetry

- Published online:

- 19 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 11 December 2025, pp 803-823

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

From Miserable Pedagogies to Anthropocene Intelligence for Universities in the Meta-Crisis

-

- Journal:

- Australian Journal of Environmental Education , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 28 November 2025, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Kant and Environmental Philosophy

- Published online:

- 01 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2025, pp 1-12

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 6 - What Is the Human Being in the Anthropocene?

-

- Book:

- Kant and Environmental Philosophy

- Published online:

- 01 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2025, pp 153-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Uncooling the planet: Rewilding for function in a post-Pleistocene climate

-

- Journal:

- Cambridge Prisms: Extinction / Volume 3 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 14 November 2025, e15

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

16 - Technologies in Environmental Governance

- from Part V - Governance by Technology

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Handbook of the Governance of Technology

- Published online:

- 30 October 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 November 2025, pp 289-306

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Kant and Environmental Philosophy

- The Climate Crisis and the Imperative of Sustainability

-

- Published online:

- 01 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 20 November 2025

4 - Climate Change Throughout Earth History

-

-

- Book:

- Essentials of Geomorphology

- Published online:

- 12 November 2025

- Print publication:

- 23 October 2025, pp 50-74

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

The anxious a priori: an essay concerning science, law, and the temporal politics of the Anthropocene polycrisis

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Global Sustainability / Volume 8 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 20 October 2025, e49

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Systemic risks and governance of the global polycrisis in the Anthropocene: stability of the climate–conflict–migration–pandemic nexus

- Part of

-

- Journal:

- Global Sustainability / Volume 8 / 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 24 September 2025, e39

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Save the Bees and Save Ourselves: Young People’s Cli-Fi as Normative Myths of the Future

-

- Journal:

- Australian Journal of Environmental Education / Volume 41 / Issue 3 / July 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 07 August 2025, pp. 477-495

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Epilogue

-

- Book:

- Law and Inhumanity

- Published online:

- 20 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 17 July 2025, pp 121-125

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Chapter 40 - Ecocriticism

- from Part VI - Critical Understandings

-

-

- Book:

- Sean O'Casey in Context

- Published online:

- 23 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025, pp 435-444

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

Through the surrealist looking glass: international theory, imagination, and the Anthropocene

-

- Journal:

- International Theory / Volume 17 / Issue 3 / November 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 July 2025, pp. 424-446

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Chapter 9 - Launching into a Brown Future

- from Part II - Transforming Genres

-

-

- Book:

- Latinx Literature in Transition, 1992–2020

- Published online:

- 19 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 03 July 2025, pp 167-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

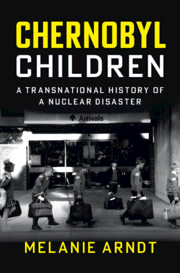

Chernobyl Children

- A Transnational History of a Nuclear Disaster

-

- Published online:

- 26 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025