Refine search

Actions for selected content:

22 results

Chapter 4 - The Athenian Empire and the Peloponnesian War

-

-

- Book:

- Reassessing the Peloponnesian War

- Published online:

- 21 August 2025

- Print publication:

- 04 September 2025, pp 63-92

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Proper and Orthodox Way of War

-

- Book:

- Warriors in Washington

- Published online:

- 23 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025, pp 125-158

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Into the Dark

-

- Book:

- Warriors in Washington

- Published online:

- 23 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025, pp 34-60

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

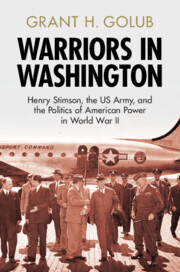

Warriors in Washington

- Henry Stimson, the US Army, and the Politics of American Power in World War II

-

- Published online:

- 23 June 2025

- Print publication:

- 10 July 2025

The Italian Resistance: historical junctures and new perspectives

-

- Journal:

- Modern Italy / Volume 30 / Issue 2 / May 2025

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 08 May 2025, pp. 125-130

- Print publication:

- May 2025

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - Double Visions (1)

-

- Book:

- Berlin

- Published online:

- 13 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 30 January 2025, pp 161-184

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

2 - Europe’s Zero Hour: Population Transfers in the Aftermath of WWII

- from Part I - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Uprooted

- Published online:

- 07 November 2024

- Print publication:

- 21 November 2024, pp 31-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - Compliance by the United States

-

- Book:

- Perceptions of State

- Published online:

- 07 June 2024

- Print publication:

- 27 June 2024, pp 104-154

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

15 - Diplomatic Negotiation

-

-

- Book:

- Diplomatic Tradecraft

- Published online:

- 15 March 2024

- Print publication:

- 28 March 2024, pp 320-349

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - Colonial Transplantation

-

- Book:

- Neutrality and Collaboration in South China

- Published online:

- 01 June 2023

- Print publication:

- 15 June 2023, pp 196-235

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Talking, Shouting Back, and Listening Better

-

- Book:

- Hanging Together

- Published online:

- 07 July 2022

- Print publication:

- 21 July 2022, pp 115-140

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - A Military Geography

-

-

- Book:

- The Architecture of Confinement

- Published online:

- 17 February 2022

- Print publication:

- 24 February 2022, pp 144-178

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

9 - Alternative Trajectories: Seeing like Parastates, Militias, and Strongmen

- from Part II - Disassemblage/Reassemblage, 1947–1953

-

- Book:

- The First Vietnam War

- Published online:

- 17 August 2021

- Print publication:

- 26 August 2021, pp 235-258

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

4 - The Great Panathenaia: Ritual and Reciprocity

-

- Book:

- Serving Athena

- Published online:

- 17 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 11 March 2021, pp 116-170

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - Creating Identities at the Great Panathenaia: Other Residents and Non-Residents

-

- Book:

- Serving Athena

- Published online:

- 17 April 2021

- Print publication:

- 11 March 2021, pp 253-313

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Contested Treaty

- from Part I - Making the Anglo-Italian Entente (1911–1915)

-

- Book:

- Britain and Italy in the Era of the Great War

- Published online:

- 08 December 2020

- Print publication:

- 10 December 2020, pp 67-72

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

5 - The Politics and Practices of Allied Relief

-

- Book:

- The Hunger Winter

- Published online:

- 04 July 2020

- Print publication:

- 23 July 2020, pp 127-163

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

8 - After North Africa

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 173-197

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

7 - The End in North Africa and the Shipping Crisis

-

- Book:

- Strangling the Axis

- Published online:

- 04 June 2020

- Print publication:

- 25 June 2020, pp 148-172

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - Buying Allies

-

- Book:

- Rules and Allies

- Published online:

- 15 July 2019

- Print publication:

- 25 July 2019, pp 203-222

-

- Chapter

- Export citation