Refine search

Actions for selected content:

4 results

Introduction

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 1-38

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Conclusion

-

- Book:

- Building the African Nation

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025, pp 293-295

-

- Chapter

- Export citation

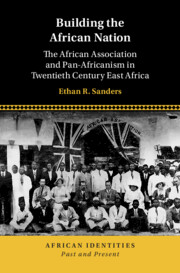

Building the African Nation

- The African Association and Pan-Africanism in Twentieth Century East Africa

-

- Published online:

- 25 July 2025

- Print publication:

- 14 August 2025

Introduction

-

- Book:

- New Sudans

- Published online:

- 06 February 2025

- Print publication:

- 13 February 2025, pp 1-28

-

- Chapter

- Export citation