Social identity can be acquired or sustained well before birth and after death, forming an ‘extended’ life course in sociological terms. Identity can come into being or be maintained through inherently material (and often visual) practices that draw on ‘body-based traces’, such as imaging a foetus through ultrasound, viewing a corpse, or tending a grave, although modes of identity (re)creation at either end of a life largely take place in the absence of the person’s body.1 In Old English poetry, a person’s social identity is often depicted as continuing beyond the limit of their embodied existence in the forms of legacy and memorialisation, seen in the building and honouring of Beowulf’s barrow, for instance (3156–77). The soul, meanwhile, reaps the rewards or punishments that have been earned over the course of its life in the world, and, in this regard, it maintains a coherent personal identity – what might be called a spiritual identity – reliant on a different kind of legacy: one’s reputation with God.

However, one of the more unsettling aspects of Old English poetry is that it often presents a person’s existence as extending after death in a manner that is less obviously a matter of social or spiritual identity, and more dominantly a material matter of physical experience on the part of a corpse. The material situation of the body is meditated upon, whether through depictions of the visitations of carrion animals, the breaking apart of the body on the pyre, or the corpse’s experience of a sleep-like state.2 Some forms of the death state, especially those characterised by extreme constriction, paradoxically begin to resemble a social death more than a physical one, in that the person’s form is materially present, but desocialised and isolated away from its community – a body without a social identity, rather than a social identity without a body.

This impression is heightened by occasional suggestions that the dead body might have enough consciousness to find the condition of death miserable. Victoria Thompson has even suggested that while the sawl or gast must depart the body in the moment of death in Old English writings, the mod (loosely, the mind, thought, or emotion of a person) may linger, noting that prose texts sometimes give the impression that there can be ‘no permanently deceased and abandoned human body, only a body in stasis’.3 For instance, the author of Vercelli Homily 9 describes dying in terms that suggest the body becomes sealed, as death ‘covers the eyes from sight and the ears from hearing and the lips from speech and the feet from walking and the hands from work and the nostrils from smell’ (‘betyneð þa eagan from gesyhðe ond þa earan fram gehyrnesse ond þa weloras fram spræce ond þa fet fram gange ond þa handa fram weorce ond þa næs-ðyrelu fram stence’).4 Similarly, the dialogue poems Soul and Body I and II are predicated on a ‘dumb and deaf’ (‘dumb ond deaf’, 64a) body witnessing the reprimanding message of the soul, ‘silenced and immobilised but conscious’.5 Elsewhere, other Old English poems also seem to present death as a kind of extreme physical impairment, differing from the disabilities of the living ‘more in degree than in kind’.6 It can be a deeply constraining experience that is simultaneously slackening, given the human body’s reliance on carefully fastened joints.7 As a weakening force, death shares much with illness: this conceptual overlap is particularly obvious in Guthlac B, possibly composed by Cynewulf, which has long been at the centre of critical discussions of death in Old English poetry, as ‘a poem on the subject of death, or the coming of Death’.8

These aspects of the presentation of death in Old English poetry have been fruitfully analysed by previous scholars, and the present chapter builds on their work in two main ways. Firstly, death is here analysed as embedded within the wider structure of the life course. This chapter is in dialogue with Chapters 2 and 3 in particular, because the death of the body is frequently positioned as the antithesis of the strength that is associated with adulthood and relates in complex ways to the loss of that force (and the witnessing of such loss) in old age. Secondly, analysis of deathlike experiences that ostensibly belong to life – such as drunkenness, despair, weariness, and sleep – can help us to contextualise the meaning of death in Old English poetry, as poets frequently forge comparisons between death and these cognate experiences, likewise socially and spiritually fraught. Moreover, threats to human power and usefulness unfold in a manner which has much in common with nonhuman forms of waste and destruction in Old English verse, such as the ravaging of buildings and objects, and the destruction of the cosmos at Judgement. Over the course of the following discussion, the creation of physical conditions of idleness and uselessness emerge as crucial to both death and deathlike conditions in Old English poetry.

In exploring these ways of apprehending death, this chapter will range more widely across Old English verse than previous chapters, reflecting the omnipresence and the variety of depictions of death across the corpus. It will nonetheless be anchored particularly in those texts most strongly concerned with cosmic order and disorder: the poems commonly categorised as ‘wisdom catalogues’, including Maxims I (Exeter Book) and Maxims II (London, British Library, Cotton MS Tiberius B.i), The Fortunes of Men (Exeter Book), and the dialogue poem Solomon and Saturn II (CCCC MS 422); and those dominantly concerned with Doomsday, particularly Christ in Judgement (Exeter Book), Judgement Day II (CCCC MS 201), and The Ruin (Exeter Book), understood as a subtly eschatological text. As throughout this book, the Riddles remain an important touchstone, and Riddles 24 (‘gospel book’) and 25 (‘mead’) make an appearance in this chapter, taken as companion pieces on the subject of death. The death state can be understood as part of wider life courses across all these texts, including through being bound up with the deathlike states of the living, forming what might be termed a spectrum of animacy.9

First, I wish to highlight the moments in which the implications for the meaning of death have arisen in previous chapters. Of course, death has been an implicit presence throughout the rest of this book – in the words of Maxims II, ‘life must be against death’ (‘lif sceal wið deaþe’, 51a).10 In complex ways, death gives the life course its limits. Sometimes this is understood by Old English poets in strictly chronological terms – that is, insofar as a ‘death-day’ (deaþ-dæg) decides the number of days which make up a lifespan – but life and death can also be pitted against each other in a kind of cosmic conflict: death, at times an indistinctly personified Death, constitutes an invasive force, cracking apart a soul and body who would otherwise remain companions.11 Previous chapters of this book have reflected more specifically on how concepts of death inform other parts of the life course. For example, death constitutes the ultimate negation of the kind of escalating power and capacity for prosperity associated with midlife, as explored in Chapter 2 with reference to Judith. The word blæd was there closely associated with the kind of flourishing that is possible in youth and adulthood in Guthlac A and Juliana, in a manner which sometimes seemed to pun on bled, blæd (‘fruit’). We can now engage more closely with those poems which forge a contrast between prosperity and later degradation, often implicating a thwarted experience of burgeoning midlife, as in the final, longest stanza of The Rune Poem:

Earth is frightening to every man, when inexorably the flesh, the body, begins to cool, the pale one to choose the earth as a bedfellow; fruits wither, joys depart, pledges fail.

The ‘cooling’ body (with colian also meaning to ‘diminish in intensity’) prompts mention of perished fruits, lost happiness, and broken social contracts.12 In other poetic contexts too, death is held in opposition to both the flourishing and maximally grown body and societal structures at their most robust.

This chapter also builds on Chapter 3’s conclusions regarding old age and death in midlife as parallel destructive fates. These two forces form, for instance, the two ‘arch-thieves’ (‘regn-þeofas’), ‘old age’ (‘yldo’) and ‘premature death’ (‘ær-deað’), named by Moses in Exodus (539–40a), while according to Hrothgar, old age shares its reign-ruining dominion with ‘adl’ (‘sickness’), ‘ecg-hete’ (‘sword-hate’), and ‘inwit-sorh’ (‘dire despair’, Beowulf, 1736–8b). Old age, illness, and sudden death thus all threaten the norm of the able, adult body.13 Chapter 3 dwelled on the implications for old age, conceived as a state of survival. Occasionally, the elderly person’s sorrow shaded into a death state through the intermediary realm of despair, as when the bereaved father of lines 2444–71 of Beowulf takes to his bed and, sorrowing, chooses God’s light (2468–71), or when the Last Survivor grieves until death floods his heart (2267–70a).

Like old age, the question of whether death has a correct place in the life course at all is theologically fraught. Paul stresses death’s alien quality in the world, hitching a ride on Adam’s sin (Romans 5:12). In a similar vein, the poet of Guthlac B dwells on death as establishing a kind of empire in the wake of sin:

Death crowded in on mankind – the enemy reigned around the world.

From this perspective, death itself is a deviance from the natural order. Nonetheless, according to Isidore and other authorities, some deaths are more unnatural than others; Isidore’s model of different kinds of death is taken up by Ælfric, by way of Julian of Toledo, as he brings together Old English and Julian’s Latin in his Sermo ad populum:

Mors acerba, mors inmatura, mors naturalis. That is in English: the bitter death, the immature death, and the natural. The bitter death is called that which happens to children, and the immature death, to young people, and the natural, that comes to the old.

In both languages, the formulation is underpinned by a fruit metaphor which works differently to the blæd concept noted in The Rune Poem; here, the human body ripens towards death, rather than towards a peak of prosperity in midlife. The adult is ‘unripe’ for death, and for the child, death is simply biter or acerbus, terms which describe sharp-tasting food.16 This tradition associates particularly painful death with the loss of a person who would otherwise have continued to flourish. Although, on some level, in the wake of the Fall, all death is deviant, some deaths (according to Isidore, Julian, and Ælfric, at least) are more premature than others.

Strict delineation between different orders of death is nonetheless rarely observed in Old English poetry, such that ‘bitter’ deaths do not come solely to children. The three youths of Daniel all face ‘the bitter death’ (‘se bitera deað’, 223a), but in the Chronicle poem The Death of Edward, the same adjective describes Edward the Confessor’s passing in his early sixties:

The noble Edward defended his homeland, country, and people, until suddenly there came bitter death, and took that noble so dear from the earth.

The death that comes to Edward is not ‘bitter’ in Ælfric’s sense of befalling a child, but the hurt it causes still involves lost potential: the bitterness is synonymous with the interruption of Edward’s reign and the dissolution of the bonds of affection he enjoyed. The language of bitterness forges a connection with food which does not please or nourish, complementing how living humans can be figured as flourishing plants or fruits, able to please, sustain, and help others.

In such ways, Old English poets frequently embed the meaning of human death in nonhuman frames of reference. This habit is perhaps most explicit in wisdom catalogues such as Maxims I, which describe, for instance, architectural and arboreal lives:

A hall must stand, age on its own, a tree lying down grows least.

One scholar has described the second line of this passage as ‘bafflingly obvious’ and another has considered it ‘a logical tautology [that] cannot meaningfully be contradicted’.18 Stark as it is, though, the claim that ‘a tree lying down grows least’ is still interpretative – it contrasts prone posture and upright flourishing in a way that recalls the semantically charged postures of the human body, which is often described as lying down in death, as we will see. A suggestive contrast is drawn between the upright posture of the hall, aligned with its ability to endure through time, and the prone posture of the tree, unable to grow. Human death is often similarly linked with other kinds of death in Old English poetry, not only in wisdom catalogues, but also in poems concerned with Doomsday.

Ultimately, this chapter highlights how poems concerned with cosmic order and its dissolution posit human death as an escalation of the loss of power similarly experienced in states of drunkenness, despair, sleep, and extreme fatigue. The wide-ranging scope of these poems leads to particularly forceful articulations of the connections between, on the one hand, human death and deathlike experiences, and, on the other, nonhuman forms of waste. They relate the death of human bodies to other forms of ruin, whereby an otherwise powerful and flourishing entity (such as the cosmos itself) is decommissioned, for all that the cosmos dissolves permanently while body and soul will be reunited at Doomsday. Before turning to these texts, this chapter will briefly highlight the language of concealment which surrounds the human death state in Old English poems, because these passages raise the issue of the dead person’s body (and to some degree the soul) as receded from view, unknowable in status. They therefore begin to implicate a loss of social identity experienced by the dead.

The Secret Lives of the Dead

As we begin to think about death in terms of social identity and a lost usefulness to others, we may note several strands of a connection between death and secrecy forged in Old English poetry. For example, when death is described in The Phoenix in a passage not known to mediate any Latin source, individuals’ bodies are plunged into a death state which resembles capture:

then death, that slaughter-hungry warrior armed with weapons, takes the life of each person and at once sends the transitory bodies, bereft of souls, into the earth’s embrace, where they will long be, until the coming of the fire, covered over by earth.

Although the deaths of saints and other holy figures are often presented as far more deliberate and peaceful than those of non-saintly bodies, the threat of concealment within the grave retains much of its force, as for St Guthlac:

This soul-house, the doomed flesh-covering, must be covered by an earth-dwelling, my limbs by a roof of clay, fast in a deathbed, dwell in a slaughter-rest.

The full ambiguity of the verb wunian here adds to the playful construction of the grave as a home experienced by the body (which itself should only really be a house for the soul). Guthlac plays with this sinister idea – if the body is only a kind of covering, what really is it that is waiting, even living, in the grave?

Adding to these epistemological ambiguities, the act of burial itself is sometimes described as a kind of hiding. The speaker of The Wanderer reports that ‘one an anguished-faced man hid in an earth-cave’ (‘sumne dreorig-hleor / in eorð-scræfe eorl gehydde’, 83b–4). In the strongly eschatological Exeter Book text known as Judgement Day I, the poet takes care to note that the spirit will return to a body even if ‘it is hidden by earth, the corpse with clay’ (‘hit sy greote beþeaht, / lic mid lame’, 98b–9a).20 Elsewhere, Metre 10 of the Old English Boethius meditates on the implications of burial as concealment as part of reflecting on the insecurity of worldly legacy; the speaker asks ‘who knows now in which mound the bones of wise Weland lie on the earth?’ (‘Hwa wat nu þæs wisan Welandes ban / on hwelcum hlæwa hrusan þeccen?’, C-Text, 42–3). If adulthood is associated with making oneself known socially (as explored in Chapter 2 in Maxims I and Beowulf), death and burial can constitute an opposite force of re-concealment, whereby the body becomes unknown.

Meanwhile, the soul’s location often becomes unknowable in a different way. In the words of Maxims II, ‘the Creator alone knows where that soul must turn afterwards’ (‘Meotod ana wat / hwyder seo sawul sceal syððan hweorfan’, 57b–8) – similar statements appear in Cynewulf’s epilogue to Juliana (695b–703a) and Bede’s Death Song, as discussed in Chapter 3, for all that saintly figures can be assured of their soul’s fate in texts like Guthlac B. Of course, the fate of the separated soul attracts a great deal of attention elsewhere in Old English verse, but the depiction of the soul’s experience of heaven and hell lies outside the scope of this study, and I wish here simply to note the occasions on which it is stressed that the location of a given soul is unknown to the rest of humanity.

Further complicating matters, a body’s experience of the grave and a soul’s experience of hell are not wholly distinct in Old English literature. There is considerable rhetorical and semantic overlap (especially in homiletic prose) between the suffering undergone by the body in the grave and the experiences of the damned soul in hell, which, according to many patristic and medieval authorities, constitutes a ‘second death’.21 In the poetic corpus, the wounds afflicted by the worm Gifer and his followers in the Soul and Body poems recall the serpents of hell, and likewise hell-like are the conditions of darkness, deprivation, and constriction.22 Meanwhile, hell’s punishment for Satan and his accomplices in Christ and Satan involves an acute consciousness of imminent death – not only ‘the shadow of death’ (‘deaðes scuwan’, 453b), but ‘the fear of dying’ (‘hinsið-gryre’, 454b).23 Heaven, by contrast, accrues significance as an escape from the twin deaths of the grave and hell.

In contrast to the epistemological anxiety which surrounds the whereabouts of the body and soul, Old English poetry often lavishes considerable attention on the fate of a person’s belongings after death.24 If much about death is unknown, a person’s possessions at least can be comprehended, managed, and organised after the person who has given them up has relinquished such clear markers of social identity. The Genesis A-poet seems to see the experiences of losing one’s life and letting go of possessions as closely connected when describing the death of Enoch, claiming that he did not die:

as people do here, young and old, when God takes away from them their possessions and substance, treasures of the earth, and their life at the same time.

There is a close association between treasure and vitality, or life force, in both Alfredian prose and certain Old English poems, as Amy Faulkner has explored.25 This is particularly clear in Genesis A, where possessing treasure appears to be metonymic for life in the world; the inheritance of treasure after a person’s death then forms a key moment in the life course of the wider community, documented with particular care by this poet.26

To return to the realm of wisdom poetry and specifically Maxims I, many of these threads come together in the following lines:

The deep way [/wave] of the dead is secret the longest; holly must be burned, the inheritance of the dead person divided. Fame [/Judgement] is best.

The uncertain and unknown status of the dead person (whether a result of their concealed body, or the unclear fate of their soul) is here contrasted with the more visible, socially intelligible division of their belongings and formulation of their legacy. A distinction is made between continued social identity (in the form of fame) and the path taken by ‘the dead’ themselves, while the burning of the holly – for all that we lack context as to what this signifies – marks a transition into reflections on how the social world manages death. The path taken by the dead themselves, though, remains inscrutable.

The remainder of this chapter is concerned with the ways in which dead bodies are ejected or excluded from human society, rather than the ways in which a person’s social identity is maintained as a kind of conceptual afterlife. It is concerned particularly with how death, presented as a condition of acutely hampered physical ability, is shown to mimic other experiences which take away a person’s vitality and efficacy. Initially, I turn to the manner in which (as already hinted at in The Phoenix) the dead are depicted as slumbering until the profound shock of Judgement, as understood in wisdom poems and poetry on Judgement Day.

Death as Sleep, Sleep as Stupor

In Old English poetry, the ‘death as sleep’ metaphor flourishes, to the extent that its status as a live metaphor is sometimes uncertain. So far, we have seen a trace of this wide-reaching rhetorical framework in The Rune Poem’s reference to earth ‘as a bedfellow’ (‘to gebeddan’, 93a). Guthlac B is also rich in the language of deathly fatigue: in his final days, the saint’s ‘strength [is] wearied’ (‘mægen gemeðgad’, 977a), he is described as ‘sickness-tired’ (adl-werig, 1008a) and ‘in need of rest’ (‘ræste neod’, 1095b). Near to his death, Guthlac states: ‘I am now greatly wearied with work [/pain]’ (‘Nu ic swiðe eom / weorce gewergad’, 1268b–9a). This kind of declaration is informed by a complex conceptual background, exploration of which has much to contribute to our sense of the meaning of death in Old English poetry.

Much of the vocabulary of sleep-as-death is not specific to a poetic register: in both poetry and prose, a wide range of terms are available to describe the dead as ‘lying’, ‘resting’, or ‘sleeping’ in death, including prominently the verbs licgan, restan, and swefan.27 Concepts of the grave and the bed overlap substantially, such that the term most often used for the grave in law codes, leger, means also ‘sickbed’ and simply ‘place of rest’.28 Sometimes prose texts meditate at length on the similarity between death and sleep. When the legend of the Seven Sleepers is narrated in Old English, for instance, considerable ambiguity characterises the condition, such that it is presented as ‘a resurrection from a sleep of death’ rather than ‘a literal long sleep’: as the leader of the sleepers remarks in Ælfric’s account, ‘now we arise from death, and we live’ (‘Nu we arison of deaðe and we lybbað’).29 This metaphorical network is not contained, then, to Old English poetry.

Furthermore, the ‘death as sleep’ conceit is seemingly omnipresent across centuries of English literature. That said, there is surprising variety between different manifestations of what might broadly be seen as the same idea. Although Old English poetry’s approach sometimes shows continuity with classical and early Christian ideas of ‘death as sleep’, it also deviates. Across Greek and Latin traditions, death is frequently compared with a sleep that is peaceful and relatively pleasant. Following Epicurus in denouncing the logic of fearing death, Lucretius offers his ‘symmetry argument’, according to which the state of non-existence after one’s life mirrors the non-existence which took place before it: ‘Is there anything horrible in that? Is there anything gloomy? Is it not more peaceful than any sleep?’ (‘Numquid ibi horribile apparet? Num triste videtur / quicquam? Non omni somno securius exstat?’).30 In early Christian contexts, for all that sin can be described as a kind of sleep of the soul, the ‘death as sleep’ metaphor is often deployed to manage anxieties about the persistence of death in the delay before the Parousia (Christ’s return), with emphasis on the temporariness of such a sleep (see, for instance, 1 Thessalonians 4:14).31 Tertullian thus presents death as reassuringly akin to sleep:

Ideo et somnus tam salutaris, tam rationalis etiam in publicae et communis iam mortis effingitur exemplar … Proponit … tibi corpus amica vi soporis elisum, blanda quietis necessitate prostratum, immobile situ, quale ante vitam iacuit et quale post vitam iacebit[.]

This is why sleep is so salutary, so rational, and is actually formed into the model of that death which is general and common to the race of man […God] sets before your view the human body stricken by the friendly power of slumber, prostrated by the kindly necessity of repose immoveable in position, just as it lay previous to life, and just as it will lie after life is past[.]32

This vision of sleep as an image of death relies upon a construction of the former as positive: ‘Indeed, we cannot possibly believe that sleep is a weariness; it is rather the opposite, for it undoubtedly removes weariness, and a person is refreshed by sleep instead of being fatigued’ (‘Neque enim credendum est defetiscentiam esse somnum, contrarium potius defetiscentiae, quam scilicet tollit, siquidem homo somno magis reficitur quam fatigatur’).33 According to this tradition, sleep is peaceful, restorative, and enjoyable – as a foreshadowing of death, it should comfort.

The idea of death as a sleep which brings a release from the world’s cares is, in large part, the version of sleep-like death that is familiar from early modern contexts, and most so from Shakespeare’s formulation in Hamlet:

Although the possibility of torturous dreams punctures its status as a peaceful condition, this sleep of death initially carries the promise of comfort and relief.35 Indeed, it is not even clearly marked out as temporary in this version of the text, although the 1603 ‘bad quarto’ of Hamlet hastens to clarify its ultimate end: ‘For in that dream of death, when we’re awaked / And borne before an everlasting judge’.36 The 1603 quarto’s implicit anxiety over the idea of an indefinite sleep of death resonates with what Rosemary Woolf has identified as an earlier hesitancy surrounding the death-as-sleep metaphor in Middle English lyrics. She observes that, for all the abiding concern with death in these texts, the presentation of death as ‘a peaceful sleep, a longed-for harbour’, occurs only in late lyrics, such as in a single stanza recorded in a sixteenth-century hand which asserts: ‘Here ys the reste of all your besynesse, / Here ys the porte of peese, and resstfulnes’ (4–5). Woolf concludes that in both date and substance, this stanza ‘belongs to the Renaissance’, given its understanding of death as ‘a release from care rather than a gateway to heaven or hell’: an approach which sits uncomfortably with the literary and cultural norms of the medieval period, and apparently at least some of those of the early seventeenth century.37

Certainly, classical or early modern modes of connecting death and peaceful sleep do not correspond with much precision to the workings of superficially similar imagery in Old English poetry. There are certainly instances of a somnolent death presented more neutrally in the Old English corpus, but these largely take the form of compact, unelaborated references to individuals consigned to the sleep of death in heroic contexts. In Beowulf, sea-monsters are ‘put to sleep by swords’ (‘sweordum aswefede’, 567a); warriors ‘sleep blood-stained’ (blod-fag swefeð’, 2060b), or ‘sleep … in darkness’ (‘swefað / … in hoðman’, 2457b–8a). In The Battle of Brunanburh, the kings and earls of Anlaf are ‘put to sleep by swords (‘sweordum aswefede’, 30a). Such turns of phrase make a fairly straightforward connection between the states of death and sleep; in this regard, they do not obviously diverge from classical and exegetical tradition of sleep as the ‘semblance of death’ (‘Mortis imago’), described as such by Alcuin.38

However, as becomes clear even in these battle poems, this kind of deathly sleep is not peaceful or restorative. Little distinction is made between the conditions of being exhausted and sleeping in death. Beowulf wishes that Hrothgar could have seen Grendel ‘fall-weary’ (‘fyl-werigne’, 962b) – glossed by the DOE as ‘slaughter-weary, exhausted by death’.39 In the mere, Beowulf observes that weariness persists for Grendel even when the life force has gone, seeing ‘the war-weary Grendel lie lifeless’ (‘guð-werigne Grendel licgan, / aldorleasne’, 1586–7a). Æschere is ‘death-weary’ (deað-werig, 2125a) after his corpse has been carried away. In Brunanburh, as the sun rises and goes down over the fallen Scandinavian and Scottish warriors, they are statically fixed on the battlefield: ‘weary, sated with war’ (‘werig, wiges sæd’, 20a). Warriors are ‘wearied by wounds’ (‘wundum werige’, 303a) in The Battle of Maldon, but the condition of death does not seem to help with this fatigue.40 Exhaustion is an experience that can persist in both life and death, and as such, it often has the effect of blurring the distinction between the two. In this sense, the weariness of death in Old English poetry is distinct from the comforting visions of death-as-sleep which surface in classical and early Christian contexts, and further distinct, of course, from the peaceful rest that can be achieved by the virtuous in the afterlife, as described in Solomon and Saturn II and widely elsewhere: ‘God will set [a person] to rest with the blessed for his merits’ (‘God seteð / ðurh geearnunga eadgum to ræste’, 168b–9).

When the language of sleep is combined with that of death outside of battle poetry, the force of this metaphor is likewise not reassuring. Also in Solomon and Saturn II, Saturn places sleep at the end of a list of oppressions:

Night is the darkest of weathers, need is the sharpest of fates,

sorrow is the heaviest burden, sleep is the most similar to death.

The direction of the simile here asserts the deathlike quality of sleep, rather than vice versa. Through syntactic parallelism, the experience is aligned with ‘night’, ‘need’, and ‘sorrow’, further connected through alliterative stress with the last of these. Sleep alliteratively collocates with sorrow elsewhere, most famously in The Wanderer, ‘when sorrow and sleep, both together, often bind the wretched solitary man’ (‘ðonne sorg ond slæp somod ætgædre / earmne an-hogan oft gebindað’, 39–40).41 Notably there, both forces fall upon the figure simultaneously; sleep is no reprieve from the former. In both texts, sleep is associated with forms of suffering.

Scholars have helpfully located this passage from The Wanderer within theological and monastic traditions connecting sleep with sin and moral death, and have similarly contextualised the presentation of sleep as unpleasant or dangerous elsewhere in Old English writings (including as part of the ‘sleeping after the feast’ theme).42 Paul pleads, ‘let us not sleep, as others do, but let us watch and be sober’ (‘non dormiamus, sicut et ceteri, sed vigilemus et sobrii simus’, 1 Thessalonians 5:6). In this tradition, to sleep is, figuratively, to disregard one’s soul. In the context of Beowulf, Hrothgar famously invokes the dangers of metaphorical sleep in his ‘sermon’, warning against the creeping growth of pride in a person’s heart: ‘the guard sleeps, the keeper of the soul; the sleep is too deep’ (‘þonne se weard swefeð, / sawele hyrde; bið se slæp to fæst’, 1741b–2). With reference to The Wanderer, Antonia Harbus notes continuity with ‘sleep as a metaphor for ignorance, death, or spiritual torpor’ in patristic writings, sometimes functioning as ‘a metaphor for a state of sin, a death of the will to what is right’.43 Evagrius Ponticus placed great emphasis on spiritual wakefulness, and his ideas were widely disseminated in the West, including in pre-Conquest England, through the writings of John Cassian – here we have another context for the dangers of ‘dulled’ and distracted perception.44 Cassian stresses that the physical phenomenon of sleep may compromise fervour and energy as much as refresh it, and for this reason monks should not return to bed after Matins:

ne purificationem nostram confessione supplici et antelucanis orationibus adquisitam uel emergens quaedam redundantia umorum naturalium polluat uel inlusio corrumpat inimici, uel certe intercedens etiam puri ac simplicis somni refectio interrumpat spiritus nostri feruorem ac tepefactos somni torpore per totum diei spatium inertes deinceps ignauosque traducat.

lest the purity which we gain through humble confession and prayer before dawn be tainted by the rising overflow of natural humours, or corrupted by the deception of the fiend, or simply that our spiritual zeal be weakened by an interval of sleep, however pure and blameless, and we be rendered drowsy and sluggish throughout the day through the after-effects of sleep.45

The Benedictine Rule also strives to impose order upon sleep, stipulating monks ‘should sleep clothed … so that the monks are always ready and, arising immediately at the signal, may hasten to be the first to do the work of God’, and, when rising ‘should gently encourage one another, to counter the excuses of the sleepy’ (‘Vestiti dormiant … ut parati sint monachi semper et, facto signo, absque mora surgentes, festinent invicem se praevenire ad opus Dei; se moderate cohortentur propter somnulentorum excusationes’).46 Anxieties about sleep and the sleepy are furthermore well supported by scripture, for instance Proverbs 6:9–11:

Usquequo, piger, dormies? Quando consurges ex somno tuo? Paululum dormies; paululum dormitabis; paululum conseres manus ut dormias, et veniet tibi quasi viator egestas, et pauperies quasi vir armatus.

How long wilt thou sleep, O sluggard? When wilt thou arise out of thy sleep? Thou wilt sleep a little; thou wilt slumber a little; thou wilt fold thy hands a little to sleep, and want shall come upon thee as a traveller, and poverty as a man armed.

In this intellectual and moral tradition, sleep threatens self-control and renders a person vulnerable; it is a precursor to attack and deprivation.

In Old English poetry on the theme of Judgement, sleep is often associated with passive vulnerability in a way that blends with the deep lethargy of the death state. In a metaphorical manoeuvre which requires God to be cast in the role of trespasser, attacker, and burglar, the Exeter Book’s Christ in Judgement begins with a Judgement scene which relies upon a metaphor of the unawares caught in sleep, drawing on Matthew 24:42–3 and reminiscent also of 1 Thessalonians 5:2:

Then with sudden danger for the world’s inhabitants, the great day of the powerful Lord will crash over shining creation with force, in the middle of the night, just as often a deceitful enemy, a daring thief, the one who moves in shadows, in the dark night, suddenly lays hands on carefree heroes bound by sleep, assaults unready men with evil.

The Old English poet here diverges from exegetical traditions, which tend to treat the verses in Matthew allegorically to avoid identifying God with the burglar figure.48 Here, the literal sense of the verses is embraced. The pejorative associations attached to witless sleep, transferred to death, seem powerful enough to mitigate the implications of aligning God with a deceptive thief.

At times, sleep can appear to be slightly more pleasurable in Old English poetry, such as in the poem known as Judgement Day II which survives in CCCC MS 201, a compilation centred on Wulfstanian texts, shaped by a pronounced interest in ‘social responsibility and good governance’.49 This text nonetheless presents sleep as both a tempting joy of this world and also a kind of spiritual suffering: the text here builds on De die iudicii, attributed to Bede – in the Latin, ‘indolent sleep, and heavy torpor, slow idleness’ (‘Somnus iners, troporque gravis, desidia pigra’, 120) are listed as among the false worldly pleasures that will be absent from hell.50 The Old English poet embellishes this with a characterisation which imbues sleep with an agency and evasive movement all of its own:

and the wretched one will flee, powerless sleep, slack with slumber, slink behind.

This is the only attestation of the word uncræftig in Old English, and its sense is potentially wide-ranging, given that cræftig carries the senses ‘strong, powerful; knowing a craft, trade or discipline, versed in, skilled; wise, learned’ (with the noun cræft found to be of importance to Andreas’ characterisations of adulthood in Chapter 2).52 Accordingly, uncræftig is capable of denoting both idleness and vulnerability, helping us to understand what might be unpleasant about sleep as a metaphor for death. The word sleac also signifies moral reprehensibility and physical passivity: when applied to people, it can mean ‘inactive, slothful’, ‘careless, negligent’; of things, ‘slow’, ‘sluggish’.53 Furthermore, sleep is presented in Judgement Day II not only as a shallow worldly comfort absent from hell, but also one of the miserable experiences absent from heaven. Bede groups somnus with thirst, hunger, and labour, also absent from heaven (130), and the poet of Judgement Day II opts for the more forceful ‘shameful sleep’ (‘heanlic slæp’, 258b). This sentiment is well attested elsewhere: The Phoenix and Christ in Judgement share a near-identical reference to both slæp and swar leger (‘oppressive sickbed’, 56; 795) missing from heaven. The group that these terms form with sorg (as in The Phoenix, 56) has been described as ‘a trinity characterized by a lack of the controlling reason of the self’.54 These conditions are presented by the poets as both reprehensible and largely undesirable.

Such a set of connotations attached to sleep have extensive implications for the death state, conceived as a closely related condition. Rather than a rest or a reprieve, sleep can itself constitute a condition of unpleasant slackness, and the death state likewise resembles a troubling experience of passivity. Christ in Judgement describes Christ raising those who have died from the earth:

Then the children of men, of all mankind, will be woken from death, to their decreed fate, terrified from that old earth, they will command them to stand up, at once from their fixed sleep.

The adjective fæst often appears in connection with sleep and death; here, it denotes a restrictive death state which contrasts with the sharp perception of Judgement. In Andreas, the language of constriction similarly shapes the episode in which Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob are woken from their death-sleep by the divinely empowered statue, as they must:55

let go of the land-rest, and gather up their limbs, take hold of their souls and youth-hood, and come forward anew, present, wise old counsellors.

These three figures seem to have physically fallen apart – they need to collect together their limbs before they can emerge. As the poet goes on to explain, they were also constricted in this sleep, such that they must stand up ‘from the dirt … quickly from the sleep that bound them’ (‘of greote … / sneome of slæpe þæm fæstan’, 794–5).56 The sleep of death is thus emphasised as a condition of deep physical powerlessness.

Even that most deliberate and immaculate of deathly sleeps, that of Christ, is described in Old English poetry in terms that suggest the vulnerability of the condition itself, as well as its connection with ongoing physical exhaustion. Christ’s death is typologically connected (by Isidore and others) with Adam’s sleep in Eden, during which God painlessly extracted his rib.57 Nonetheless, the way in which Christ’s condition is described in, for instance, The Dream of the Rood, relies heavily on the heroic register of sleeping death – he is laid down ‘limb-weary’ (‘lim-werigne’, 63a) by his followers and rests ‘for a while, tired after that great struggle (‘hwile … / meðe æfter ðam miclan gewinne’, 64b–5a).58 Christ’s experience of death is usually handled by critics as atypical and separate from other deaths in Old English poetry. Jonathan Wilcox, for instance, does not discuss The Dream of the Rood in a study entitled ‘The Moment of Death in Old English Literature’, despite observing that this literature ‘does not particularly dwell on the precise moment of death’: this is of course especially true of The Dream of the Rood, which avoids narration of Christ’s death, skipping over it by way of a temporal conjunction: ‘after he had sent forth his spirit’ (‘siððan he hæfde his gast onsended’, 49b, emphasis mine).59 The language of weariness here, as elsewhere in Old English verse, provides a rhetorical grey area between conditions of living and death, useful for the poet of Rood in navigating the theologically fraught issue of the nature of Christ’s death, but also linking with the representation of death elsewhere in the corpus.

The death of Christ is also depicted (allegorically) as a sleep in The Panther in the Exeter Book, in a way which asserts the extreme privacy to which the creature retreats; it thus achieves a similar effect to The Dream of the Rood, where the sleeping Christ is closely watched:

Happy with its fill, when it partakes of food, after that feast it always seeks out a resting place, a secret space under a hill-cave; there the people’s warrior turns in a slumber, engaged in sleep for the interval of three nights. Then, on the third day, the bravely bold one stands up, swiftly out of sleep, enriched with power.

Sleeping after a feast, this figure retreats to a location so secluded that it removes the problem of vulnerability in somnolence. The creature awakens refreshed, and the phrase ‘slæpe gebiesgad’ is interpreted in the DOE as ‘engaged in sleep, asleep’, but in poetry the more usual sense of gebysgod is ‘troubled, afflicted’, and it appears in The Phoenix with the sense ‘burdened’.61 Even in this most purposeful and restrained of sleeps, some sense of difficulty attaches to the experience.

If the death state is often understood as resembling a sleep in Old English poetry, this is by no means the association familiar from early modern contexts. Rather than figured as a restorative reprieve from the world, death is constructed as a continuation of the constricting passivity associated with normal sleep. In the poetry surveyed here, especially that concerned with Judgement Day, sleep blurs with death in a manner far from reassuring.

Deathly Drunkenness

In 1 Thessalonians 5:6–7, Paul warns not only against spiritual vulnerability figured as a sleep state, but – in the same breath – against the dangers of drunkenness. Old English poetry is similarly quick to present drunken torpors as shading into a death state. Scholars have previously investigated the significance of drink as ‘a death-bearing thing’ (‘cwylm-bære ðing’, according to Ælfric) in Old English writings.62 It remains to wonder, however, what the implications of this kind of statement are for the idea of death itself, rather than for ideas of drunkenness. As with the sleep metaphor, much of the force of comparisons between the two states rests on lost control and functionality.

As an explicit piece of commentary on the phenomenon of drunkenness, we can begin with the Exeter Book’s Riddle 25, usually now solved as medu (‘mead’), with the misleading metaphorical centre understood by Niles to be a wrestler.63 The poem begins with accounts of the material’s origins (as nectar) in woods and hills, and its transportation under rooves and into barrels. As it progresses, however, the text dwells with increasing intensity on the shared semantic territory between death and drunkenness. Rather than a wrestler, the overwhelming force of death itself may be understood as the riddle’s metaphorical centre:

Now I am a constrictor and a striker; quickly, I throw a young man to the earth, sometimes an old man. Quickly he finds, he who struggles against me and contends against my violent force, that he must seek the earth with his back, if he does not cease from his folly beforehand. His strength is stolen, strong in speech, his power is taken away, he does not have mastery of mind, feet, or hands. Learn what am I called, who on earth so binds young men, stupid after blows, by day’s light.

I would suggest here that the line which asserts the capacity of this force to lay low ‘a young man …, sometimes an old man’ (‘esne …, hwilum ealdne ceorl’, 8) plays with death’s reputation as an indiscriminate assailant of people of all ages, ‘young and old’ (‘geonge and ealde’, as Genesis A put it, 1207a), while also signalling the differing sensitivities to alcohol of young and old.64 The passage’s binding imagery is consistent with descriptions of death as holding people fæst, explored earlier. Moreover, contact with the earth is referenced as a salient part of this experience, with emphasis increasingly (and helpfully, from the point of view of the solver) placed on this person being cast upon the earth rather than under it. Initially, the young and old men are cast ‘to eorþan’ (8a); then, in an ominous reference to supine posture, the struggling figure ‘must seek the earth with his back’ (‘hrycge sceal hrusan secan’, 11); finally, the young men are bound ‘on eorþan’ (16a). Although on can sometimes have the sense ‘in’, it is certainly not under, and as if to drive home the point, the figure’s bound state is said to be inflicted by the light of day (17b). One of several clues to the ‘real’ answer of this riddle is therefore given by the person’s situation as proximate to concealment under the earth, but falling just short of that fate. Like any riddle, the poem’s meaning is not constrained by its solution – this text could even be understood to offer a ‘small allegory’, to borrow a phrase from Niles, for mankind’s disastrous encounter with death, especially if we see the figure’s punishment for his unræd (‘folly’, or ‘ill-advised plan’) as quietly suggesting the impudence of the Fall.65 But even in more general terms, Riddle 25’s references to a figure committed to the earth may have more ominous implications than Niles perceives when viewing this particular riddle as a comparison between the effects of medu and those of ‘a ruffian who delights in binding and flogging others’, with the text designed to ‘raise a smile’.66

If Riddle 25 is instead taken as poem indirectly about death, with something to say about that condition, certain themes emerge which resonate with other parts of this chapter and this book. The riddle’s incapacitated figure loses his strengu (13a) and mægen (14a); he also no longer has ‘mastery of mind, feet or hands’ (‘modes geweald, fota ne folma’, 14b–15a). Such elements align with what scholars have previously noted about the death state in Old English poetry: it is often presented as a condition of extreme physical weakness, a restrictively slack and disorganised state. It also offers another way of refining the ‘one sex’ model for this context, with extreme physical weakness associated most clearly with the death state, rather than conditions of childhood or old age. It is, after all, in descriptions of the dead that we find the clearest negation of the active form of the human body, the most extreme possible point on a spectrum of animacy. While old age brings some skills, pleasures, and redeeming qualities in addition to physical weakness, a state of death offers none. It remains now to consider what else can be understood of this network of associations between states of drunken stupor and death in Old English poetry, particularly with regard to the idea of the unused and decommissioned body.

Some Old English poems use drinking to signal wickedness; others simply recommend restraint.67 The Exeter Book is particularly rich in poems which ‘warn of the dangers of overindulgence in alcohol’, particularly its association with ‘social discord’.68 There is considerable continuity here with exegetical and homiletic prose, which sees overdrinking as causing both personal and social harm. Bede is emphatic on this point in his Commentary on Proverbs, enthusiastically expanding on a passage that describes alcohol as a substance which is pleasant to consume, but one which ‘in the end will bite like a snake and will spread abroad poison like a basilisk’ (‘in novissimo mordebit ut coluber et sicut regulus venena diffundet’, 23:32).69 According to Proverbs 23:34, alcohol interferes with good judgement and good conduct, framed as the skill of steering: ‘thou shalt be as one sleeping in the midst of the sea and as a pilot fast asleep when the stern is lost’ (‘eris sicut dormiens in medio mari et quasi sopitus gubernator amisso clavo’). Drinking certainly leads to a profound lack of awareness and capacity for choice in contexts such as Judith, as discussed in Chapter 2: Holofernes’ men lie ‘as if struck by death, emptied of every good’ (‘swylce hie wæron deaðe geslegene, / agotene goda gehwylces’, 31b–2a), having abandoned what Bede might refer to as ‘the ship of the body’ (‘navem corporis’).70

The poet of Genesis A takes a particularly pejorative stance when describing Noah’s experience of being constricted by drunkenness, elaborating extensively on the Vulgate source.71 Noah’s drunkenness is signposted as a condition of decline when the poet stages an abrupt shift between his profitable work on the vineyard (also expanded from scripture) and his subsequent intoxication:

Then Noah began afresh to establish a home with his near relatives and to till the earth for food for them, he struggled and worked, set up a vineyard, sowed many seeds, sought eagerly when the green land brought him beautifully bright fruits, glorious gifts of the year. Then it came about that the blessed man became drunk with wine in his dwelling, slept feast-weary, and pushed off the bedclothes from his own body, as was not appropriate; he then lay limb-naked. He little perceived what miserably took place within his tent, when the head-dizziness in his breast seized his heart, in that holy one’s abode. His mind constricted very much in his sleep, so that he could not remember to cover himself with clothes, with his hands, and conceal his shame[.]

The status of drunkenness as an oblivious, unguarded, and vulnerable state is clear here, and overlaps somewhat with exhaustion – Noah is ‘feast-weary’ (‘symbel-werig’, 1564a). His lack of self-consciousness seems to constitute a turn away from society, as shame has no force to him. An ‘entropic logic’ seems to shape Genesis A, as Andrew Scheil has noted, in that the poem stages the continual corruption of humanity. This specific passage seems to be modelled on the Cain and Abel episode, connecting Noah’s decline into drunkenness with the murder of Abel.72 When compared with the Lot episode, further parallels emerge. The passage describing Lot’s decline into a drunken state is missing from the manuscript, but from what remains there is evidence of a similar structure in which morally dangerous inebriation comes hard on the heels of the optimistic establishment of a home. Lot and his daughters depart Zoar to seek a dwelling, which they find in a mountainside cave:

There the blessed Lot lived, faithful to his covenant, beloved by the Ruler, for a great count of days, and his two daughters.

The Book of Genesis offers no time frame here. The Vulgate notes that Lot ‘abode in the mountain’ and ‘in a cave’ with his daughters (‘mansit in monte, mansit in spelunca’, 19:30), while some Old Latin versions use the verb habitare, closer to the Old English poet’s sense of continued dwelling here.73 The poet amplifies Lot’s successful settlement and habitation, such that he occupies the cave for a great number of days, with this phase then interrupted by the scene of drunkenness. In doing so, the poet calls back to the Noah and Ham episode, and more indirectly to the moral decline of Cain and the Fall in Eden itself, as the intrusions of drunkenness echo the intrusions of death into the world.

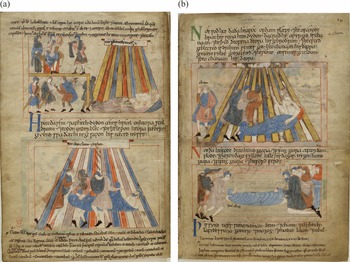

Parallels between Noah’s drunkenness and the experience of death surface also in a visual context, although not prominently in the illustrations of Junius 11. The illustrator of the Noah and Ham episode in Junius takes care to demarcate visually Noah’s bedbound state as reprehensibly sensuous: Noah is supported by a large pillow and has pulled back his blanket, resulting in a luxurious cascade of folds.74 The scene is handled differently in the illustration in the Old English Hexateuch, seemingly produced at St Augustine’s in Canterbury around the second quarter of the eleventh century. Here, Noah’s drunkenness is incorporated into the wider visual strategies which shape the illustrations of this codex. As Rachel Crabtree has observed, the illustrator of the Hexateuch employs a sustained pattern of spatial organisation towards the beginning of the volume (fols 10v–12r), resulting in ‘a stylised representation of Life on the left hand half of the page and Death on the right’ – in this scheme, ‘“Life” is characterised by a seated figure, surrounded by wife and sons, and “Death” by a swathed body lying across the middle of right-hand section, supported by two figures’.75 Shortly following this sequence, Noah’s condition of drunkenness is placed in visual parallel with his death state, across folios 17v–18r (see Figure 3). Especially given that, nine folios earlier, Abel is depicted as naked in death (fol. 8v), a visual language is shared here between drunkenness and death. In the lower images of both pages, Noah is held suspended aloft, just as repeatedly elsewhere in the codex ‘the shrouded body appears peculiarly weightless’.76 The illustrator of the Hexateuch, like the poet of Genesis A, makes use of a shared visual motif to depict the two conditions.

Figure 3 The Old English Hexateuch. London, British Library, Cotton MS Claudius B.iv, fols. 17v–18r.

We can now turn to the best-known meditation on death and drunkenness in the Old English poetic corpus: the depiction, in The Fortunes of Men, of sudden death brought about through heavy drinking.77 The details surrounding the experience(s) narrated here are obscure:

One is deprived of life by the sword’s edge, on the mead-bench, angry and steeped in ale, a man full of wine – his speech before was too rushed. One, through the server’s hand, is a mead-light warrior; then he does not know measure in determining his mouth with his mind, but must very sadly part from his life, endure great suffering, stripped of pleasures, and men call him a self-killer, mourn with their mouths the mead-light one’s drunkenness.

Although they run together, the passage may describe two different figures. For the first man, it is specifically his hasty words that bring about his death by the sword. The second sum of the passage ushers in a more general idea of drinking as a kind of self-killing; this person is light or giddy with mead (with this same compound, meodu-gal, used to describe Holofernes in Judith, 26a), and as a result is divided from his life. Again, it is the ability to speak deliberately which is lost: this figure relinquishes his ability to manage his mouth (52b–3). The result is an excess of words which leads to a profound deprivation, as the figure is ‘stripped of pleasures’ (‘dreamum biscyred’, 55b). This paradox resembles that which is highlighted in Riddle 25, where for the drunken figure, ‘strength is stolen, strong in speech’ (‘Strengo bistolen, strong on spræce’, 13). The deathly experience of drunkenness is notable for its status as a fundamentally immoderate and disorganised experience.

Crucially, the passage in Fortunes describes a social loss. It turns to those who are still in control of their mouths, and who agree amongst themselves that the man is a ‘self-killer’ (‘self-cwale’, 56a). They are said to ‘mourn with mouths’ (‘mænað mid muþe’, 57a) his drunkenness; in addition to the senses ‘to lament’ or ‘complain’, the verb mænan can mean ‘to mourn’ in response to a death – it is used in Beowulf in this sense (2267b, 3149, 3171). His death, whether literal (as a result of his inebriation) or figurative (in the inebriation itself) is disturbing on a communal level. In the shared semantic territory this passage nurtures between death and drunkenness, a key role is played by the negation of functional social relationships. The condition of drunkenness is connected with disruptive intracommunal violence, and eventually a judgement is made by peers that the death (whether literal or metaphorical) is a loss to the group. Even more than sleep, drunkenness is deathly for its disruption of social bonds. Having noted this theme in Fortunes, this chapter will now turn away from death framed as cognate with the sluggish and unproductive experiences of the living, and consider its depictions as simply costly in itself: the ultimate experience of waste.

Idle Hands: Ruin and Uselessness

Judgements as to the social and economic cost of death can be found widely in Old English poetry. This chapter has so far traced such ideas of loss at the respective intersections of death and sleep, and death and drunkenness – where death proper meets other forms of compromised liveliness. As will now be seen, there are many more places where death is more straightforwardly described as a kind of decommissioning, of making-idle. These statements are particularly pronounced – as will be seen – in the apocalyptic imagery of The Ruin, as well as the reflections on cosmic order and divinely ordained destruction in Maxims I.

We might initially also think of Grendel’s death, which is framed explicitly in terms of function, as Beowulf does not wish for the creature to depart alive, ‘nor consider[s] his life-days of use to anyone’ (‘ne his lif-dagas leoda ængum / nytte tealde’, 793–4a). This is set against a background in the rest of poem in which people are useful to others: nytt describes the ‘duty’ of the thane that carries the cup in the hall (494b), while Beowulf’s own resistance to Grendel is described as a ‘special duty’ (sundor-nytte’, 667b). The death of Æschere, a ‘treasure-giver’ (sinc-gyfa, 1342a), is framed by Hrothgar in terms of his value to the community, specifically the way his hand facilitated people’s hopes: ‘now the hand lies still, which for every one of you fulfilled your desires’ (‘nu seo hand ligeð, / se þe eow welhwylcra wilna dohte’, 1343b–4). The meaning of death is thus elided with the dismantling of previously pleasurable and productive social relationships.

There are analogues in Old Norse poetry for the idea of a useless death state. Most strident on the subject is the eddic poem Hávamál, which explicitly compares and contrasts death with disability:

The lame man rides a horse, the handless man drives a herd, the deaf man fights and succeeds; to be blind is better than to be burnt: a corpse is of no use to anyone.78

Here, the Old Norse cognate of the Old English adjective nytt is employed, similarly used to describe the value of the living. Parallels also surface in Latin traditions, as when Isidore accounts for the term defunctus:

Defunctus vocatus, quia conplevit vitae officium. Nam dicimus functos officio, qui officia debita conpleverunt; unde est et honoribus functus. Hinc ergo defunctus, quod ab officio sit vitae depositus, sive quod sit diem functus.

The deceased (defunctus) is so called, because he has completed his part in life. Thus we say that those who have completed services they owed have ‘discharged their duty’ (functus officio); whence also the phrase ‘having held (functus) public office.’ Hence therefore ‘defunct,’ because such a person has been ‘put aside from his duty’ (depositus officio) in life, or else because he has fulfilled (functus) his number of days.79

Such a perspective aligns well with New Testament parables of the world figured as a workplace, including a vineyard (Matthew 20:1–16; Matthew 21:33–46; Mark 12:1–12; Luke 20:9–19), or a field of crops (Matthew 13:1–13; Mark 4:1–20; Luke 8:4–15). At the same time, Isidore’s notion of being prematurely ‘put aside’ from the duty of living resonates with the idea of a ‘bitter’ death, in the sense of the unpalatable extinguishing of an otherwise successful, beloved, and promising social actor, as in the case of the king’s thwarted prosperity in The Death of Edward.

Analogous perspectives can be found in modern cultural and sociological theory with perhaps unexpected force, given that such theorists primarily describe societies shaped by industrialised capitalism. Michel de Certeau, for instance, meditates on the conceptual overlap between the indolent and the dead:

Along with the lazy man, and more than he, the dying man is the immoral man: the former, a subject that does not work; the latter, an object that no longer even makes itself available to be worked on by others … the dying man raises once again the question of the subject at the extreme frontier of inaction, at the very point where it is the most impertinent and the least bearable.80

Old English poetry is similarly troubled by death as a form of terrible, frustrating, and at times almost repulsive idleness. As in de Certeau’s formulation, the death state in these contexts is framed an intensification of other modes of opting out of social relations.

The most extended Old English poetic meditation on the once socially useful, now decommissioned, is the damaged text towards the end of the Exeter Book known as The Ruin. Critics have long read The Ruin as expressing nostalgia for a celebrated past, but Niles urges us to consider the ‘city of the dead’ it describes as one punished by God, in response to the moral degeneracy of a people ‘proud and light with wine’ (‘wlonc ond win-gal’, 36a) – with alcohol here again presented as a kind of spiritual death which causes a literal death.81 The people to whom the poem refers may have been specifically deserving of such destruction, but Niles recognises that the poem also supports a broader reading of ‘human civilization as something that is splendid in potentia but that is always in ruins or in the process of decay’; in Augustinian terms, this is the City of Man understood against the City of God.82 The cosmic ruin that will come at the end of the world is obliquely mentioned early in the poem, as the point at which the earth’s grip will finally be released:

The earth’s grip has the master builders – wasted away, passed away – the ground’s hard grasp, until a hundred generations of people have departed.

It is notable here and throughout the text how individuals are described with reference to their social functions as warriors, builders, and those who sustain social and physical structures. As the architecture falls away from its purpose, so do the human figures:

Slaughter fell widely, days of sickness came. Death seized all of the sword-brave men. Their defences became wasted places, the city rotted. The restorers fell, armies to the earth. Therefore, these dwellings fall desolate, and the red-arched roof of the vaulted rafters sheds its tiles.

The collapsed structures of the ruined building parallel both the ruined social bonds between its inhabitants, and the violated constraining architecture of the human body itself.83 Parallels with the seething motions of human distress suggest themselves in the imagery of welling water towards the damaged ending of The Ruin, as Lockett has pointed out:

the stream warmly spouted its ample surge; the overflow enveloped all in its bright bosom where the baths were, hot at its heart.84

A connection might further be made here with heolfor (‘blood, gore’) as ‘the ultimate fate of an attacked [human] body whose boundaries have been entirely burst apart’, a substance described as hat in both Andreas (1241a, 1277a) and Beowulf (849a, 1423a), mingling with the surging water of Grendel’s mere in the latter.85 The moral significance of the baths themselves in The Ruin is unclear – they may be associated with luxury, such that the poet’s formulation ‘that was convenient’ (‘Þæt was hyþelic’, 41b) pointedly gestures towards a worldly pleasure.86 If so, the bathing scene joins the drinking in creating conditions of moral danger which precipitate physical destruction.

The poet of The Ruin is keenly interested in the dynamics of use and pleasure, framing death and destruction as the apex of uselessness. Similarly, in The Wanderer, the material achievements of worldly communities are squandered, as the speaker reflects:

So, the shaper of men has laid waste to this dwelling place, until, lacking the noise of the city-dwellers, the old work of giants stood idle.

The adjective idel is often found translated as ‘empty’ here, but the word denotes also ‘idle’, ‘worthless, useless, ineffective’, a counterpoint to the sense of purposeful, intentional effort which informs geweorc.87

These patterns of thinking about waste on an individual, social, and cosmic scale again find a correlate in twentieth-century thought, this time in the philosophy of Georges Bataille, who trained as a medievalist and whose early engagement with medieval sources (especially Old French chivalric poetry and the theology of Aquinas) seem to have informed his later work.88 Bataille stresses the inevitability of waste in the world, and of the impossibility of indefinitely conserving resources. He traces how various cultures have negotiated the fact that ‘if [a] system can no longer grow, or if the excess cannot be completely absorbed in its growth, it must necessarily be lost without profit; it must be spent, willingly or not, gloriously or catastrophically’.89 The useless squandering of resources can take many forms, including gift-giving, but the most ‘remarkable’ form of excess, for Bataille, is death. His reflections on the subject move between human and nonhuman referents:

Of all conceivable luxuries, death, in its fatal and inexorable form, is undoubtedly the most costly. The fragility, the complexity, of the animal body already exhibits its luxurious quality, but this fragility and luxury culminate in death. Just as in space the trunks and branches of the tree raise the superimposed stages of the foliage to the light, death distributes the passage of the generations over time. It constantly leaves the necessary room for the coming of the newborn, and we are wrong to curse the one without whom we would not exist.90

Bataille is not concerned here with the Christian God, instead seeing the excessive activity of the world to begin with the sun – the ultimate dispenser of energy without return; nonetheless, many of his remarks parallel the observations of Old English texts such as Maxims I:

He increases infants, when early-disease takes them; this is why so many of mankind come to be on the earth. There would not be a limit to the progeny [lit. ‘timber of children’] in the world if he did not decrease it, who made this world. Stupid is the one who does not know his Lord, so often does death come unexpectedly.91

Compared to Bataille’s reflections, these lines similarly understand human habitation of the world as a kind of excessive flourishing which brings inevitable waste, anchoring this thought in an arboreal metaphor. From such a perspective, death is built into the system; it is part of the cosmic order. This passage does not simply articulate horror or distaste at the inescapability of death in the world, but something approaching respect, in a way that a modern reader might find unsettling, particularly given the reference to the early death of children. Attended to carefully, though, it prompts consideration of whether Old English poetry might appreciate worldly destruction, rather than simply lamenting it, more than its scholars tend to acknowledge.

Indeed, similar concern with divinely mandated destruction can be found in the Exeter Book riddle collection, in a manner which has the potential to nuance some critical orthodoxies regarding Old English poetry’s ‘elegiac’ leanings and concern with transience, typically understood as ‘regret for the brevity of human life and human joy’.92 Rather than solely constituting a lamentable problem resulting from the Fall, the only appropriate reaction to which is the redirection of hopes towards heaven, the presence of destruction in the fallen world is, at times, presented as part of the spectacle and variety of Creation, and a testament to divine power. When wind is loosened on the world in the third section of Riddle 1 (‘Wind of God’), it devastates cities and woods, and in churning the sea destroys an entire ship:

There a ship may expect a dire conflict, if the sea bears it at that terrible time, full of souls, so that it must become deprived of power, injured mortally, ride foamy on the backs of the waves. Then a certain terror is shown to men, when I must run strong on the hard path. Who makes that still?

This servant of God is an engine of waste, congruent with contemporary understandings of wind as a dangerously destructive force.94 The inevitability of ruin is here integrated into the disorderly order of the cosmos. Similarly, in Riddle 38, as in its source, Aldhelm’s Aenigma 100 (Creatura), the power of God to curtail and contain is as impressive as his creative capacity: the speaking Creation announces that God alone can ‘increase my strength, tame my force, so that I may not exceed myself’ (‘ecan meahtum, / geþeon þrymme, þæt ic onþunian ne sceal’, 90b–1). Creation itself encompasses both productive and destructive aspects: it can exist without eating, but it states, ‘I can consume more forcefully and eat as much as an old giant’ (‘Ic mesan mæg meahtelicor / ond efnetan ealdum þyrse’, 62–3).95 Violence, consumption, and the curtailment of existence is here part of the fabric of the created world.

Theories of waste have on occasion been brought in connection with Old English literature, as when Susan Signe Morrison dwells upon the deliberate ‘waste’ of the treasure taken out of a system of use at the end of Beowulf, connecting this sacrifice with the conceptual waste formed by periods of cultural upheaval.96 I wish to suggest that depictions of death in Old English often suggest the squandering of the otherwise useful and productive in a way that pre-empts Bataille’s model, whether such squandering comes about through death or other, comparable conditions. The condition of the drunken figure in Riddle 25 is seemingly comparable to death in its deactivation of the body, paralleling how, in Bataille’s terms, the consumption of alcohol constitutes a form of useless destruction – it ‘deprives us, for a time, of our strength to produce’.97 Riddle 25 describes the figure as having no control over ‘feet nor hands’ (‘fota ne folma’, 15a), and as Neville has previously observed, this phrase is reminiscent of Grendel’s killing of Hondscio, as he wholly consumes the ‘unliving one … feet and hands’ (‘unlyfigendes … / fet ond folma’, 744a–5a).98 A similar kind of threat to the total body is found as Abraham fetters the ‘feet and hands’ (‘fet and honda’, 2903b) of Isaac, described by way of another un-prefix as an ‘ungrown child’ (‘bearn unweaxen’ 2872a), at the close of Genesis A. Here, the context is explicitly sacrificial, while Hondscio’s death on Beowulf’s watch has been perceived as a ‘seeming sacrifice’.99 Bataille stresses how moments of sacrifice perversely confirm the social value of the destroyed entity: in the case of a sacrifice, ‘destruction … eliminat[es] his usefulness once and for all’.100

The meaning of a sacrificial victim thus lies in the curtailing of their future existence, or in other words the lif-dagas that are being given up; in the Exodus-poet’s description, Abraham demonstrates:

that he did not deem his life-days more beloved than obeying Heaven’s King.

In this context, the sacrifice of the ‘ungrown offspring’ (‘eaferan … / unweaxenne’, 412b–13a) is consciously and deliberately undertaken: in other words, ‘the sacrificer give[s] up the wealth that the victim could have been for him’.101 Elsewhere in Old English poetry and prose, martyrs give up the wealth of their own worldly lives, having removed themselves from earthly socio-economic systems.102 More broadly speaking, as explored earlier, death creates waste against the volition of humans and (if they have not prepared spiritually) their expectations. Described as a ‘slaughter-hungry warrior’ (‘wiga wæl-gifre’, The Phoenix, 486a), in Bataille’s terms, death ‘consume[s] profitlessly whatever might remain in the progression of useful works’.103 As extravagant consumption, death is a fundamental condition of worldly existence.

Dissolution, Consumption, and Carrion

For all that human remains must be revived at Judgement, the initial fate of the human body in Old English verse is often to be literally consumed: eaten by worms in more homiletic contexts, or devoured by beasts of battle in a heroic register. Even the verb meltan, used of corpses on funeral pyres, has the sense ‘to melt, become liquid, be consumed’, and of food, ‘to digest’.104 It is not surprising, given these trajectories, that a number of the life narratives of the Exeter Book Riddles culminate in a scene of consumption, including the ‘oyster’ riddle with which this study began.105 Indeed, at Judgement, even the cosmos meets a similar fate:

All the earth will shake, also too the hills will fall and collapse, and the slopes of the mountains will bend and dissolve, and the terrifying noise of the violent sea will greatly disturb the mind of every person.

Mountainsides ‘will dissolve’ or ‘will be consumed’ (‘myltað’, 101b), while hills ‘fall’ (‘dreosað’, 100a), just as the ‘high arch has fallen’ (‘steap geap gedreas’, 11b) in The Ruin. The abundance of seething imagery in Judgement Day II, as in The Ruin, connotes mental agitation and other disordered conditions of the individual human body. Like those of human death, the processes associated with the cosmic dissolution of the apocalypse are not wholly new (the sea has churned before, the earth has shaken; humans have been constricted through sleep, disease, or drunkenness), but the end is an escalation of previous, lesser destructions.

A few final comments will here be offered regarding the activities of carrion beasts, the significance of their consumption of bodies, and their association with efficacy, hope, and contentment, particularly in The Fortunes of Men. The raven, eagle, and wolf operate as emotional foils to the dead more widely in Old English. As Mo Pareles has pointed out, when, in Beowulf, Wiglaf’s messenger describes to the Geats the pleasure of the beasts that will follow the invasion of the Swedes, these carrion animals ‘provide a counterpoint of vitality and abundance to Geatish death and poverty’, in a manner which is further heightened by the poet’s indication of intimacy and collaboration between these animals:106

but the dark raven, keen over the doomed, speaking many things, saying to the eagle how he succeeded in eating, when he plundered the slaughter with the wolf.

At a moment, then, when ‘fighting and agential’ human bodies are reduced to food, their intimate relationships are superseded by avian relations of the same kind.107 Old English characterisations of the raven, the eagle, and the wolf are generally distinguishable from their Old Norse counterparts by their emphasis on their experience of expectation and anticipation.108 Indeed, in Beowulf, the thwarting of the hope which the elderly father placed in his son, now ‘young on the gallows’ (‘giong on galgan’, 2446a), is clearly offset by the raven as the new beneficiary of the son’s form, to whom he becomes a ‘solace’ (‘hroðre’, 2448a). The old man contrastingly cannot ‘await’, or ‘place hope in’ another heir (‘gebidanne’, 2452a). Insofar as the raven exemplifies hopeful expectation, it draws attention to precisely what has been lost from the community in this instance of a death: the present and future of the person who has died.

In Fortunes, an efficient and agential raven likewise highlights what has been lost in death as it shreds the body of the figure on the gallows:

One must ride upon the wide gallows, suspended in death, until his soul-hoard, his bloody bone-coffer becomes broken. There the raven seizes his eyes, dark-coated it slits him open, soulless; he cannot with repulsion defend himself with his hands against the air-robber, his life is departed, and he insensate, hopeless of spirit, waits for the outcome, pale on the beam, covered by slaughter-mist. His name is weary [/cursed].

Again, death is presented as physical incapacity, as this figure is ‘insensate’ (‘feleleas’, 40a).109 Some kind of wish to repel the raven is implied, but the figure’s hands are unable to intervene. The ultimate result is that the lifeless person – still referred to as he – becomes ‘hopeless’ (‘orwena’, 40b), entering an emotional condition of despair. This figure’s name may even be ‘weary’ (wērig, 42b), a usage of the adjective which Fulk has doubted, positing instead ‘cursed’ (*werge) – nonetheless, given the close associations between death, fatigue, and expenditure outlined in this chapter, we might consider accepting the exhausted status of this figure’s name at face value.110 The individual’s social identity is wholly spent, and the raven’s dexterous and efficacious eating only counterpoints his helpless and hopeless status.

A structurally similar scene unfolds in Riddle 24 (‘gospel book’) in a way which ultimately points its audience towards a spiritually robust mode of thinking about death. Here, destruction and consumption in the worldly sphere pave the way for flourishing spiritual growth, in a manner that evokes a human death, specifically a martyrdom.111 The riddle begins:

A certain enemy stripped me of life, deprived me of my world-strength, afterwards drenched me, dipped me in water, drew me out again, set me in the sun, where I quickly lost the hairs that I had.

Afterwards the severe edge of a knife cut me, impurities ground away; fingers folded me, and the bird’s joy often made tracks over me with successful drops, over the burnished brim, swallowed tree-dye, a share of the streams, stepped again on me again, travelled a dark track.

Feathers playfully figured as plundering carrion animals can be found elsewhere in the Riddles, but this text gives us a full-fledged ghost of a carrion scene.113 The creature is killed and then rent by sharp edges, at the mercy of the ‘bird’s joy’ (‘fugles wyn’, 7b) – on one level, a kenning for a quill feather, but on another, a misdirection to the joyful expectation of the raven or the eagle. The helpless condition of the speaker is offset by the visiting bird making a trail with ‘sped-dropum’ (8a), that is, ‘successful markings’ or ‘markings which bring success’, a foil to the deep passivity of the riddle-creature’s body, again suggesting joyfully efficacious carrion birds. It nonetheless becomes clear (far clearer than in Fortunes) that the spiritual life course of the dead creature extends beyond the bounds of its broken body: