“You and I come out publicly in a pre-emptive interview where you talk about evolving on women’s issues…You reached out to me to help understand rapidly evolving social mores around sexual misconduct because you are a good and decent person (as evidenced by your life’s work making films on important social issues and extremely generous philanthropy).” – Lisa Bloom memo to Harvey Weinstein, December 2016

Lisa Bloom was known as an attorney who helped victims of sexual harassment and assault get their days in court. She successfully advocated on behalf of the women who accused Bill O’Reilly of harassing them in the workplace (Cullins Reference Cullins2017); she represented a former staffer who accused Representative John Conyers of sexual misconduct (Stump Reference Stump2017); and she helped women accusing then-candidate Donald Trump of sexual assault go public with their accusations (Sathish-VanAtta Reference Sathish-VanAtta2016). Bloom’s pro-women reputation so thoroughly preceded her that W Magazine declared Bloom and her mother, feminist advocate Gloria Allred, “the Defenders of Women” (Pechman Reference Pechman2017). But in December 2016, Bloom quietly took on a new client: movie mogul Harvey Weinstein, around whom rumors of assault and harassment were beginning to swirl (Garber Reference Garber2019). When she took the job, Bloom assured Weinstein that her presence on his legal team would shore up his feminist bona fides and make accusations of misbehavior look misplaced (Kantor and Twohey Reference Kantor and Twohey2019). She promised that having such a powerful advocate for women’s rights supporting him would give Weinstein cover to deny the accusations and avoid reputational damage.

The logic behind Bloom’s assurances to Weinstein seems clear, as it can be difficult to argue with a woman vouching for a man’s respectability on women’s issues. But can women representing men accused of misbehavior actually legitimize outcomes favoring those men? In the legislative arena, the answer appears to be yes, because women are valued for their expertise on women’s issues (Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022), and female legislators’ inclusion in deliberations involving anti-feminist outcomes increases the perceived legitimacy of those outcomes (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). This is precisely why women often become the “face” of policies perceived as hurting or inhibiting women’s rights (Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021). We suspect that in the judicial arena, where the law is supposed to reign, a female attorney defending such policies is an even stronger validator of outcomes that disfavor women. Attorneys work within a legal system functioning on the belief that its actors are legally principled and work within the confines of the law (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013; Scheb and Lyons Reference Scheb and Lyons2000). Female attorneys arguing in favor of anti-women outcomes should thus be uniquely positioned to validate anti-women decisions and the judicial system that made them. After all, such mismatched representation should underscore the correctness of the decision and the notion that the law values fairness and equality over personal bias or desires.

To test these theories and better understand how attorney gender, clients, and judicial outcomes intersect to shape people’s perceptions of the courts and their decisions, we designed a survey experiment in which we asked 1,395 participants to read an article about a circuit court ruling in a sexual harassment case. In the article, we varied the gender of the attorney, the position for which they advocated, and whether the attorney won or lost the case. After reading the article, we asked participants questions about their feelings regarding the correctness of the decision and the fairness of the process used to get there, known respectively as substantive and procedural legitimacy. We find that, contrary to our expectations, attorney gender has little impact on people’s views of the courts’ legitimacy, and women advocating for anti-feminist causes do not really legitimize those outcomes. Any differences that do exist reflect expected gendered preferences, with one notable exception: women express higher feelings of procedural and substantive legitimacy when they see a woman represent an anti-feminist interest and win. On the whole, however, our findings suggest the judiciary is different than legislatures, and deploying female attorneys for symbolic reasons has limited effect on people’s reactions to judicial decisions and the process used to reach them.

By conducting this research, we contribute to the wider literature on symbolic representation in important ways. First, we expand the scope of the symbolic representation literature to the courts, which have received limited attention but are worth deeper examination. Broadly speaking, the judiciary is a unique institution because it is tasked with protecting individual rights in spite of popular support, while simultaneously depending on popular support for its authority (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013). Consequently, understanding if and how descriptive representation influences popular acceptance of the judiciary’s work is crucial for understanding the judiciary’s ability to protect those rights (Chen and Savage Reference Chen and Savage2024; Zilis Reference Zilis2021). Research establishes that an opinion writer’s identity characteristics can affect opinion acceptance (Boddery and Yates Reference Boddery and Yates2014; Ono and Zilis Reference Ono and Zilis2022; King and Schoenherr Reference King and Schoenherr2024), and a burgeoning literature on attorneys suggests they also play a part in the legitimation process (see Scott, Lane, and Schoenherr Reference Scott, Lane and Schoenherr2025). Leaning on symbolic representation literature, which suggests that those who bring up issues can affect popular acceptance of them, we introduce a new dimension to scholars’ study of the relationship between judicial representation and outcomes. Simultaneously, by focusing on the people who bring up the issues, we push scholars working in legislative and executive politics to think about how different advocates shape public response to political institutions and their decisions.

Second, by showing if, how, and for whom female attorneys can influence the legitimacy of anti-feminist rulings, we contribute to an ongoing conversation about when identity influences popular response to court rulings. Research shows that when people have information about who won a court case and who (or what) influenced the court’s eventual decision, they use identity characteristics such as partisanship or gender to process the decision and respond to it (Boddery, Moyer, and Yates Reference Boddery, Moyer and Yates2020; Zilis Reference Zilis2018). This work suggests some portion of the public does not respect a diverse decision-making process, because they do not believe women and racial and ethnic minorities can impartially judge people who share their identity characteristics (Ono and Zilis Reference Ono and Zilis2022). Consequently, one could wonder if women arguing against women’s interests might be able to validate anti-feminist decisions by playing against popular bias; indeed, research suggests that female judges can do exactly that (Matthews, Kreitzer, and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020). By shifting analysis toward the people advocating for those positions and finding evidence to the contrary, however, our research indicates that public response to court rulings is more complicated than existing work might suggest and thus worthy of deeper examination.

The Legitimizing Effects of Women’s Inclusion in Politics

Research has long established that women’s inclusion in the judiciary changes the way the courts do business. As judges, women are more likely to rule in favor of victims of sexual harassment and convince their male colleagues to follow suit (Boyd Reference Boyd2016; Boyd, Epstein, and Martin Reference Boyd, Epstein and Martin2010); they are better at pulling parties into agreement (Boyd Reference Boyd2013); and they garner more popular support for their decisions than those attributed to male judges (Boddery, Moyer, and Yates Reference Boddery, Moyer and Yates2020). As attorneys, women raise different issues (Litman, Murray, and Shaw Reference Litman, Murray and Shaw2021), offer subject-matter expertise that judges respect (Patton and Smith Reference Patton and Smith2017), and are consistently rated as more effective leaders and collaborators than their male counterparts (Rhode Reference Rhode2017). While gendered differences are not universal and are mostly tied to identity-relevant issues where lived experience matters (Haire and Moyer Reference Haire and Moyer2015; Szmer, Sarver, and Kaheny Reference Szmer, Sarver and Kaheny2010), these differences are meaningful enough to suggest that gender diverse judge and attorney corps modify and shape substantive judicial outcomes.

While it is clear that gender diversity in the judiciary plays a role in shaping substantive outcomes, scholars understand less about gender’s role in shaping symbolic attitudes toward the legitimacy of courts and their decisions (but see Chen and Savage Reference Chen and Savage2024; Lane and Schoenherr Reference Lane and Schoenherr2025). To what extent could women’s inclusion in the federal judiciary broadly shape public views of judicial legitimacy and support for the courts? Existing literature on the linkages between descriptive and symbolic representation suggests institutional diversity affects how people view decision-making bodies and the degree to which the public accepts their decisions (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Scholarship also indicates that when women are included in positions of power, the public views those institutions as more legitimate, more trustworthy, and more open and responsive to public needs (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler Reference Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler2005; Atkeson and Carrillo Reference Atkeson and Carrillo2007; Stauffer Reference Stauffer2021). This work also shows that women’s inclusion induces greater levels of participation and engagement with an institution (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2021; Campbell and Wolbrecht Reference Campbell and Wolbrecht2006; Reingold and Harrell Reference Reingold and Harrell2010; Mariani, Marshall, and Mathews-Schultz Reference Mariani, Marshall and Mathews-Schultz2015). Put simply, the public prefers institutions that have women.

Moving beyond these more general attitudes, Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo (Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019) note two distinct forms of legitimacy where women’s inclusion is particularly important: procedural and substantive legitimacy. The first, procedural legitimacy, ties to the fairness of the rules, procedure, and process used to reach a decision. When women are included in deliberations, individuals express more positive views of the decision-making process, viewing it as more fair and valid (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). This may be the result of gender stereotypes; consider, for example, that the public perceives lower levels of corruption in legislatures or cabinets that include women, at least partially because stereotypes about women’s honesty and integrity lead people to view women as “clean” outsiders (Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Barnes, O’Brien and Taylor-Robinson2022; Valdini Reference Valdini2019; Barnes and Beaulieu Reference Barnes and Beaulieu2019; Funk, Hinojosa and Piscopo Reference Funk, Hinojosa and Piscopo2021). Indeed, as Stauffer (Reference StaufferForthcoming) argues, many of the stereotypes the public holds about women, such as honesty, willingness to compromise, and empathy, map onto characteristics Americans see as desirable in decision making (see also Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002). Even the mere belief that women are included in a legislature can lead to people viewing it as more ethical, willing to compromise, less beholden to special interests, and more likely to take input from constituents (Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming). Altogether, these findings suggest that women’s inclusion in office can shape evaluations of procedure because the public assumes women bring certain (desirable) characteristics to decision-making contexts.

The second distinct form of legitimacy is substantive legitimacy, which refers to views about the degree to which the outcome produced by an institution is the “correct” one, regardless of the procedure used to produce it.Footnote 1 Here, scholars believe women’s presence is especially legitimizing for outcomes that are related to women’s interests. Essentially, when the decision being issued impacts women, the inclusion of women in the deliberations sends a signal that the institution is capable of producing the correct outcome for the group (Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming). This effect is especially pronounced in instances where women’s rights are being restricted, with women’s participation in anti-feminist causes effectively legitimizing outcomes that harm “their group” (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Matthews, Kreitzer, and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020).

Does Gender Diversity Influence the Legitimacy of the Courts?

Understanding which factors affect public views of judicial legitimacy is critical because the federal courts rely on popularly elected officials to enforce their decisions (Hall Reference Hall2010; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008), and elected officials are more likely to do so when courts appear legitimate (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira1992). Judicial legitimacy stems foremost from popular belief that people will receive their fair day in court (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2013); as long as people believe the courts are procedurally fair, they accept losses as the cost of living in a law-based society (Gibson Reference Gibson, Bornstein and Tomkins2015). Making the judiciary look like an apolitical arbiter of the law is thus a preoccupation for anyone who works within it. For judges, this means consistently reminding the public of their unique role in the political system, from wearing robes to disguise their individuality (Gibson, Lodge, and Woodson Reference Gibson, Lodge and Woodson2014), to speaking the language of the law (Zilis Reference Zilis2015), to banning cameras from their courtrooms (Black et al. Reference Black, Johnson, Owens and Wedeking2024), to reminding everyone that judges make decisions based on the law (Armaly and Schoenherr Reference Armaly and Schoenherr2025). While research mostly focuses on judges’ role in legitimation, attorneys also help maintain the system’s legitimacy. Law students’ professionalization process and subsequent admission to the bar require lawyers to present themselves as protectors of the fair administration of justice.Footnote 2 More cynically, lawyers also financially benefit from a functioning and powerful legal system and thus have every incentive to help maintain it.Footnote 3

Research suggests women’s presence in decision-making bodies can also legitimize institutions in a number of ways, but much of the existing work on this topic focuses on women joining legislative or executive institutions. Should we expect to see similar legitimizing dynamics at play for the courts? Work on judicial diversification indicates there are real ways new faces can impact legitimacy. Shortell and Valdini (Reference Shortell and Valdini2022) show that individuals are more likely to view national courts positively when there is a greater proportion of women serving, though this effect is limited to those with relatively lower levels of hostile sexism (see also Scherer Reference Scherer2023). Putting women on high courts leads to increased belief that women can and should be lawyers and judges, which normalizes their appearances within the judiciary and decreases their notoriety (Escobar-Lemmon et al. Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Hoekstra, Kang and Kittilson2021; Kenney Reference Kenney2013), and having women in judgeships also leads to more women filling the judiciary’s supporting roles (Lane and Schoenherr Reference Lane and Schoenherr2025). Moreover, senators and presidents campaign on their diversification records, suggesting that adding women to the bench is politically popular, too (Badas and Stauffer Reference Badas and Stauffer2023; Bratton and Spill Reference Bratton and Spill2002; King, Schoenherr, and Ostrander Reference King, Schoenherr and Ostrander2025). Such research suggests that, at least in some circumstances, descriptive representation positively shapes people’s views of the judiciary and their willingness to support the institution itself.

At the same time, however, public belief in judicial fairness and equity also leads people to question the procedural and substantive value of a diverse bench. While Americans are legal realists who understand political preferences influence the judicial decision-making process, they still expect judges to make legally principled decisions (Bartels and Johnston Reference Bartels and Johnston2020). Judicial passivity — the fact that judges, unlike legislators or executives, cannot actively pursue issues (Rice Reference Rice2020) — contributes to the belief that judging is principled and different from politicking. Consequently, judicial inclusion is not something the public necessarily demands, as there is a belief that identity should not influence the decisions judges reach. To that end, people express higher support for merit-based systems that perpetuate all-male judiciaries than they do for selection systems that favor inclusion (Arrington Reference Arrington2021). Additionally, some people believe women’s inclusion in the judiciary induces bias, as they assume female judges’ “feminine natures” supersede their dedication to the law (Ono and Zilis Reference Ono and Zilis2022). Alternatively, those same people are also more trusting of anti-feminist decisions that come from women judges (Matthews, Kreitzer, and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020), and those decisions make people who are typically supportive of diversification wary of it (Chen and Savage Reference Chen and Savage2024). Judges consequently tend to lay low and hide within their institution so they avoid provoking these reactions, which they can do in a world where the media offers limited coverage of their work (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). Altogether, research suggests that while Americans theoretically appreciate the diversification of the judiciary, many are also skeptical that diversification will result in them receiving their fair day in court.Footnote 4

Of course, judges are not the only people who work within the judiciary. And importantly, unlike legislatures or the executive branch, the judiciary’s policy proposals do not come from the people who ultimately enact the final policy. Attorneys, not judges, are the ones who propose policies and offer guidance on how to enact them (Marshall and Hale Reference Marshall and Hale2014), and they make decisions about how to argue cases effectively so they and their clients get the outcomes they want (Johnson, Wahlbeck, and Spriggs Reference Johnson, Wahlbeck and Spriggs2006). They are also responsible for their clients and take an oath to fiercely advocate for them, which means attorneys are, in fact, required to use the law in any way they can to achieve those outcomes (Lane and Schoenherr Reference Lane and SchoenherrForthcoming). Attorneys are thus an excellent judicial parallel to elected officials who are similarly responsible for producing desired outcomes in ways that federal judges are not. Importantly, attorneys’ position as well-trained, specialized advocates also creates an air of seriousness and commitment to working within the confines of the law, which underlines the principled nature of the judiciary, too (Hazelton and Hinkle Reference Hazelton and Hinkle2022). Is it possible that female attorneys’ advocacy for particular policies or positions can increase the substantive and procedural legitimacy of the courts?

We suspect the answer to the question is yes, though only in limited circumstances. Broadly, we would expect that learning about attorneys and their advocacy work simply reinforces people’s pre-existing beliefs in the judiciary’s legitimacy; there is something about seeing someone working within the confines of the law that makes people believe in the judiciary’s legitimacy (Krewson Reference Krewson2019). In the case of “women’s issues” specifically, popular expectation in women’s prowess over such areas should make women seem especially trustworthy on such issues (e.g., Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022). Consequently, seeing someone advocate against expectations should emphasize the principled nature of the law (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming). That is, if a woman is advocating against women’s interests, then her argument must be the best possible legal answer.Footnote 5 Put differently, we suspect that harassers like Harvey Weinstein hire female advocates because they expect those advocates’ presence will bolster the arguments made in their favor and help legitimize favorable substantive outcomes in ways that male advocates cannot. Simultaneously, we also expect that a woman’s role as advocate in cases like these will also increase belief in a legitimate process, as the woman’s presence signals a commitment to legal correctness that might not otherwise exist.

Attorney Gender and Substantive Legitimacy: Is the Decision Correct?

Starting first with substantive legitimacy — that is, the correctness of the decision — we expect people will view rulings that work against women’s interests as more legitimate when the attorney arguing against those interests is a woman. As Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo (Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019) note, people view anti-feminist outcomes as more legitimate when women participate in the decision-making process that produced them. In cases where women’s rights get rolled back, political actors may strategically use descriptive representation to argue that such policies are actually in the group’s interests; consider that some of the strongest advocates for anti-abortion policies in state politics have been conservative women purposefully deployed to shut down arguments the policies are anti-women (Matthews, Kreitzer, and Schilling Reference Matthews, Kreitzer and Schilling2020; Reingold et al. Reference Reingold, Kreitzer, Osborn and Swers2021). As we suggested earlier, we believe that women’s presence in court arguing in favor of an anti-woman outcome should be particularly meaningful and signal the correctness, if not inevitability, of such an outcome. That is, a female attorney representing an anti-feminist position should validate and legitimize an anti-women ruling, just like women’s inclusion in decision-making bodies legitimizes anti-feminist policy outcomes.

H1: In contexts where women successfully represent an anti-feminist interest, people will report increased levels of substantive legitimacy, relative to when a man represents an anti-feminist position.

Similarly, we expect that female attorneys who represent feminist positions and lose can delegitimize a court decision. Because the public expects women will be experts on topics involving their own issues (Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022), their position in a harassment case again signals the correctness (or incorrectness) of the court’s decision. By ruling against such a “fair and expert” advocate, then, the court should look like it made a bad decision, and people’s support for that decision will consequently slide.

H2: In contexts where women unsuccessfully represent a feminist interest, people will report decreased levels of substantive legitimacy, relative to when a man represents the feminist position.

While having a woman represent an anti-feminist (feminist) interest could be potentially legitimizing (delegitimizing) in some instances, we expect these effects might be contingent on respondent gender. In particular, we expect that attorney gender will play a greater role in men’s evaluations of substantive legitimacy compared to women. Indeed, Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo (Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019) find that men are more likely to draw on information about gender composition to evaluate whether decision-making bodies have appropriately represented women’s substantive interests. For issues that relate to or disproportionately impact women, women are more likely to have crystallized opinions about what the correct outcome is. While women may disagree on what the “correct” outcome might be, they are more likely to have an opinion in the first place, and thus are less likely to draw on attorney gender to formulate an opinion. For men, however, the “correct” outcome involving women’s rights might be less clear because their opinions are less crystallized. Here, seeing a woman representing an anti-feminist position may legitimize that position by signaling that some women support the outcome. Moreover, the broader literature on gender stereotypes suggests men are more likely to rely on simplistic gender cues and stereotypes than women because it is easier for them to apply these stereotypes to “out-groups,” whereas women understand their group is inherently more complex and less reducible to simple stereotypes (Boyd, Collins Jr., and Ringhand Reference Boyd, Collins and Ringhand2018; Dovidio and Gaertner Reference Dovidio and Gaertner2000).

H3: The legitimizing effect of attorney gender on anti-feminist outcomes will be stronger for men compared to women.

H4: The delegitimizing effects of attorney gender on feminist outcomes will be stronger for men compared to women.

In contrast, when a woman unsuccessfully represents an anti-feminist position, we do not expect to observe an effect. In these instances, the advocate for the anti-feminist outcome matters little because the court preserved women’s interests anyway. Likewise, when a woman is seen successfully representing a “pro-woman” outcome, we do not expect to see attorney gender play a role in perceptions of substantive legitimacy. The attorney gender cue is less useful here because the court reached what would be considered the default “correct” decision for the group.

H5: In contexts where women unsuccessfully represent an anti-feminist interest, people will report similar levels of substantive legitimacy compared to when a man represents an anti-feminist interest.

H6: In contexts where women successfully represent a feminist interest, people will report similar levels of substantive legitimacy compared to when a man represents a feminist interest.Footnote 6

Attorney Gender and Procedural Legitimacy: Was the Process Fair?

Beyond the implications that attorney gender might have for substantive legitimacy, we also expect the attorney’s gender will have ramifications for perceptions of procedural legitimacy — the fairness of the process used to reach the decision. As Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo (Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019) show, the public views decision-making bodies that exclude women with skepticism, even when producing substantively desirable policy outcomes — something simply looks unfair about a group legislating without women. We similarly expect that in cases adjudicating women’s interests, the gender of the attorneys making the arguments will likewise influence the courts’ procedural legitimacy.

As we previously noted, the public expects women to be subject matter experts on issues particularly salient to women (Strickland and Stauffer Reference Strickland and Stauffer2022). Female attorneys’ presence in cases involving those issues should thus affect people’s willingness to accept the outcomes for which they advocated. However, we also suspect that a woman attorney winning her case will send signals about the process by which the decision was reached. Because of their presumed expertise, when women prevail in arguing for (or against) feminist outcomes, a win also signals that the court relied on the people most knowledgeable about the issue. That is, the female attorney’s win signals the court reached the decision the “right” way. Conversely, seeing the court reject a female attorney’s position on a women’s issue may send signals that the institution is not open and responsive to the voices of women on the issues where they have expertise — that is, that the court decided the decision the “wrong” way. Indeed, recent research highlights the linkage between the public’s views of procedure and substance in legislative contexts (Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming).

Moreover, we expect how women attorneys fare in court to serve as a cue about whether the judicial process is truly open and accessible to women’s interests. While in a legislative context, inclusion in and of itself might signal that the process was open to women’s interests (see Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019), the context of attorneys is somewhat distinct. When women are included in decision-making bodies, they play a role in determining the ultimate outcome. While attorneys make arguments in hope of shaping outcomes, they, unlike legislators, lack ultimate control over final outcomes, which sit with judges. This means that simply seeing women attorneys participating in the judicial process may not necessarily signal procedural legitimacy in instances where the woman loses. Indeed, seeing women consistently lose in court may actually send signals of a process that is biased against women’s interests and repeatedly rejects them.

H7: People will view outcomes as more procedurally legitimate when female attorneys successfully advocate a position (regardless of whether they are advocating for feminist or anti-feminist positions) than when male attorneys win by making the same arguments.

H8: People will view outcomes as less procedurally legitimate when female attorneys unsuccessfully advocate for a position (regardless of whether they are advocating for feminist or anti-feminist positions) than when male attorneys win by making the same arguments.

Motivation and Approach

To address these hypotheses, we designed a 2 × 2 × 2 survey experiment in which we asked participants to read a newspaper article that discussed a circuit court ruling in a workplace sexual harassment case and then respond to it. We focused our analysis on workplace sexual harassment because it is an issue traditionally associated with women (Boyd, Epstein, and Martin Reference Boyd, Epstein and Martin2010; Haire and Moyer Reference Haire and Moyer2015), and there are clear feminist outcomes (the court rules in favor of the person being harassed), and clear anti-feminist outcomes (the court rules in favor of the harasser or the employer that hired them), which offers us the best opportunity to examine the role that attorney gender might play in validating judicial outcomes and the processes used to get there.Footnote 7

We used Lucid Theorem to recruit a sample of 1,395 participants to complete our survey between September 23 and October 14, 2022 (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019).Footnote 8 After consenting to take the survey, participants answered a handful of questions about the Court before they were randomly sorted into their treatment groups and asked to read a newspaper article.Footnote 9 In the article, participants read about an attorney, named either Kevin or Katherine Bailey, who was responding to a federal circuit court ruling that either mandated employers terminate employees found guilty of sexual harassment or gave employers discretion over what to do with harassing employees.Footnote 10 The attorney offering their thoughts, who represented either the employer (the anti-feminist condition) or the woman bringing the sexual harassment complaint (the feminist condition), either lamented the outcome when they lost or praised it when they won.Footnote 11 The article included a professional photo of the attorney whose response got covered.Footnote 12 A breakdown of the treatment conditions is available in Table 1.

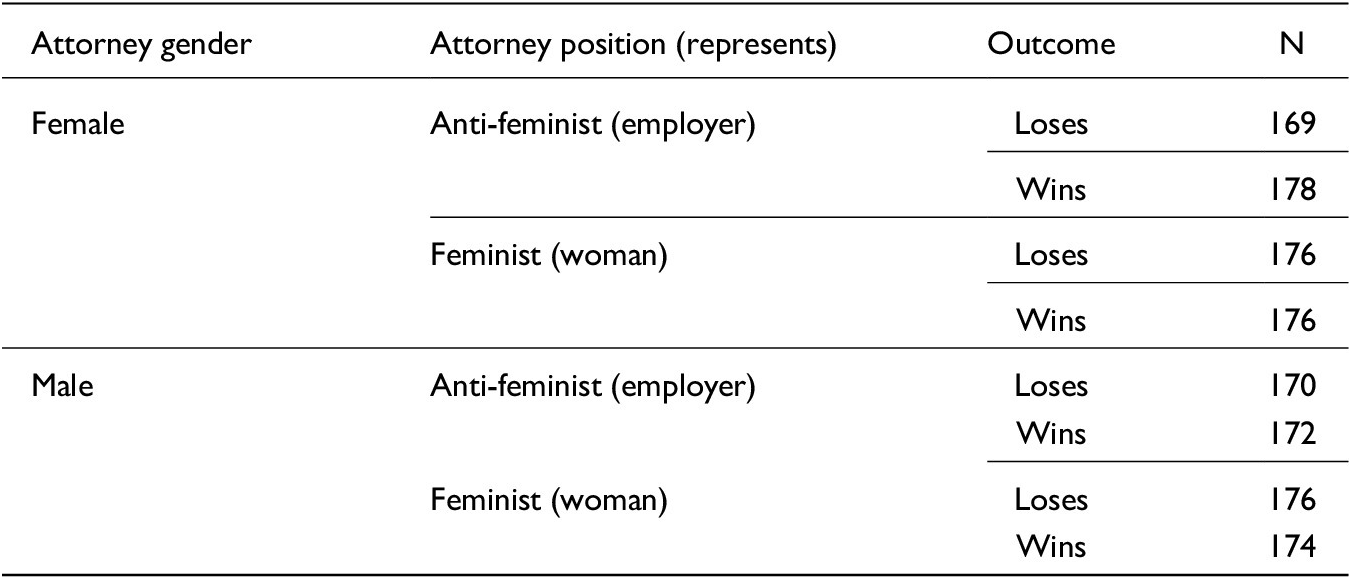

Table 1. Experimental conditions

After reading the vignette, participants answered a series of questions regarding their feelings of substantive and procedural legitimacy toward the federal court system. These questions are based on Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo (Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019), with the only modifications being the target of the questions. When asking participants about their perceptions of substantive legitimacy, we prompted them to provide their level of agreement with the rightness of the decision for Americans and women before asking them to rate the fairness of the decision. Specifically, participants responded to the following items:

-

• The court made the right decision for Americans. [strongly disagree to strongly agree]

-

• The court made the right decision for women. [strongly disagree to strongly agree]

-

• How fair was this decision to women? [very unfair to very fair]

Participants rated their level of agreement and perception of fairness on a four-point Likert scale, with higher values equaling higher levels of agreement and fairness. These responses are highly correlated and load together onto a single factor, so we generate a substantive legitimacy composite score that runs from one to four.Footnote 13

After asking participants about their perceptions of substantive legitimacy, we asked participants about their feelings of procedural legitimacy using three different prompts:Footnote 14

-

• Thinking about the gender of the attorney, how fair was the decision-making process? [very unfair to very fair]

-

• Thinking about the gender of the attorney, the court can be trusted to make decisions that are right for Americans. [strongly disagree to strongly agree]

-

• The court can be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country. [strongly disagree to strongly agree]

Again, we asked participants to rate their level of agreement or perception of fairness on a four-point Likert scale, with higher values indicating higher levels of agreement and fairness. And, similar to our measure of substantive legitimacy, we generated a procedural legitimacy composite score that runs from one to four because the responses were again highly correlated and loaded together onto a single factor.Footnote 15

Between the questions asking about perceptions of substantive and procedural legitimacy, we asked participants to identify the gender of the attorney mentioned in the article, which served as our manipulation check.Footnote 16 After answering the post-treatment questions about substantive and procedural legitimacy, we debriefed the participants and told them the news article they read was fictional before thanking them for completing the survey.

Results: Substantive Legitimacy

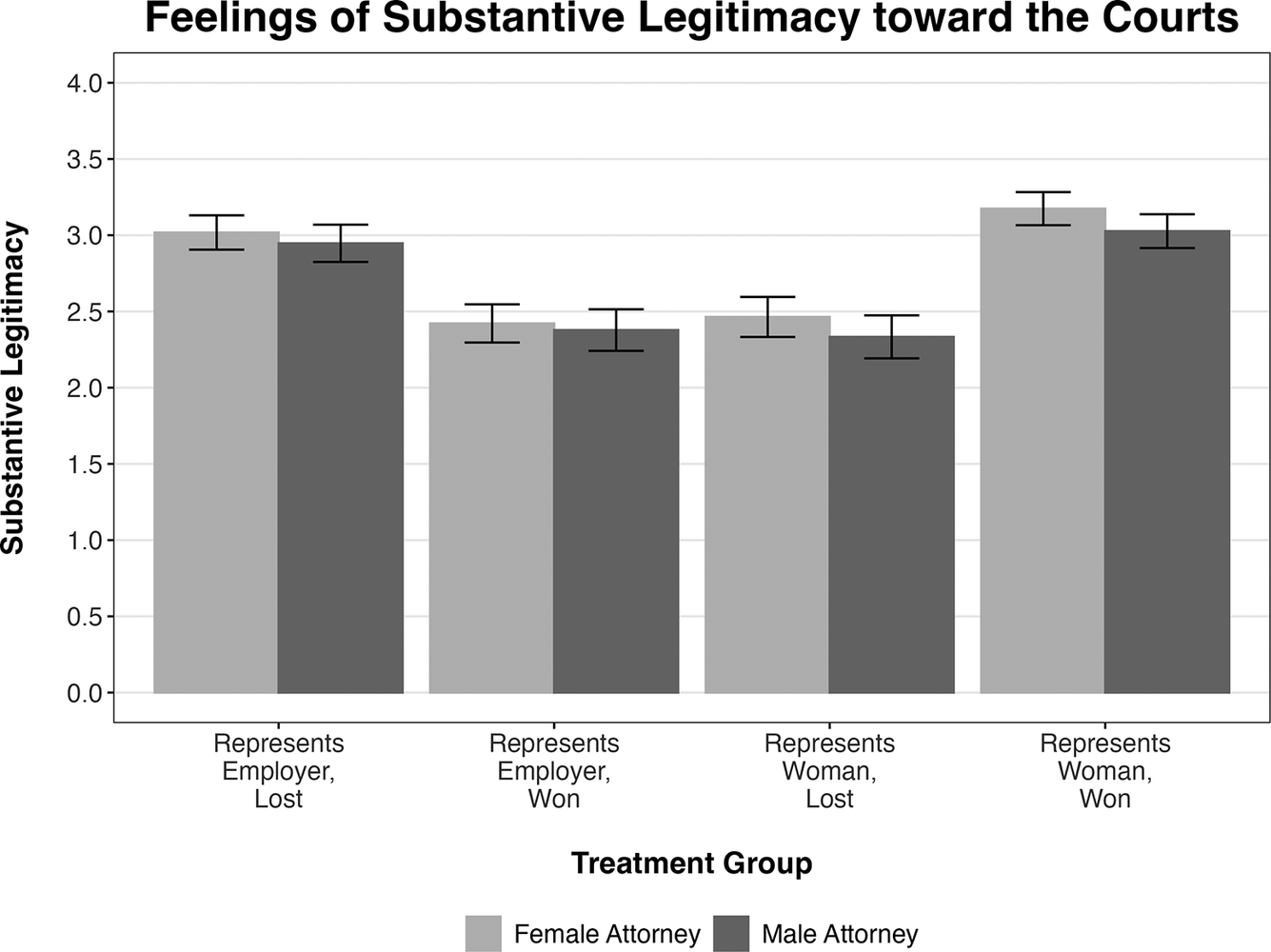

To examine participants’ feelings of substantive legitimacy toward the Court, we use our four-point composite scale, where higher scores indicate higher levels of legitimacy.Footnote 17 We begin by examining how attorney gender influences feelings of substantive legitimacy broadly. As we show in Figure 1, and contrary to our Hypotheses 1 and 2, we find no evidence that attorney gender significantly influences feelings of substantive support for the courts following a sexual harassment decision, no matter what decision is reached.

Figure 1. Mean differences in participant feelings of substantive legitimacy toward the courts after reading about a sexual harassment decision.

Contrary to our expectations in Hypothesis 1, a female attorney taking an anti-feminist position and winning does not increase feelings of substantive legitimacy compared to when a male attorney does the same. Further, we do not find support for Hypothesis 2, as a female attorney unsuccessfully representing a feminist interest does not decrease levels of substantive legitimacy relative to when a male attorney does. Taken together, we do not find evidence of a [de]legitimization effect based on the gender of the attorney and case outcome. Contrary to evidence found in legislatures where women’s inclusion can legitimize anti-woman outcomes (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019), female attorneys representing anti-feminist interests do not legitimize outcomes, nor does losing a case representing feminist interests delegitimize outcomes with regard to the courts.

Unlike Hypotheses 1 and 2, which predicted a [de]legitimizing effect due to attorney gender, we predicted in Hypotheses 5 and 6 that substantive legitimacy would not change in cases where either a female attorney represented anti-feminist interests and lost or represented feminist interests and won relative to a male attorney. We find this to be the case in both instances, as seen in Figure 1. That is, as expected, there is no significant difference in views of substantive legitimacy when women unsuccessfully argue for anti-feminist outcomes or when women successfully represent feminist ones. When the court reaches the default “correct” decision for the group, attorney gender is not a useful cue and fails to influence views of substantive legitimacy.

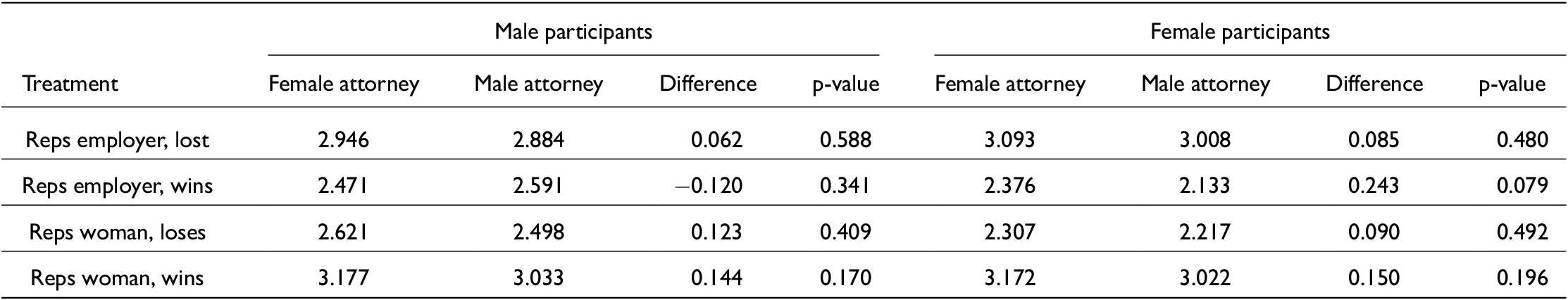

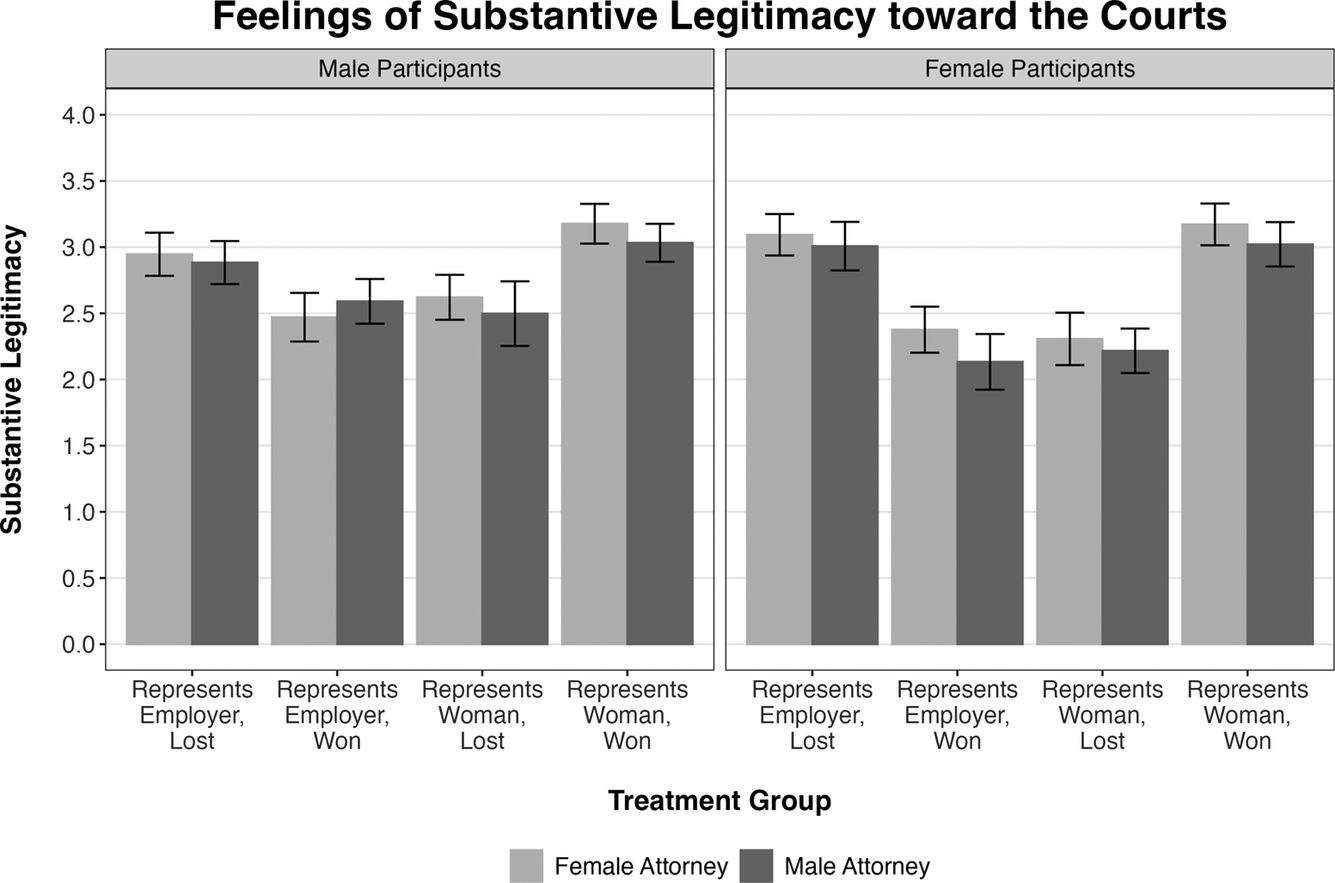

Moving beyond broad support, we suggested in Hypotheses 3 and 4 that male and female participants would rely on the cue of attorney differently when evaluating substantive legitimacy. More specifically, we expected that the cue of a female attorney would be stronger for men. Contrary to our expectations, Table 2 and Figure 2 show minimal evidence that men and women make different inferences based on the gender of an attorney. Specifically, Table 2 and Figure 2 demonstrate the within-group comparisons of how male or female participants view substantive legitimacy based on a male or female attorney, who they represent, and the eventual case outcome. In all but one instance, neither male nor female participants seem to base their views of substantive legitimacy on the gender of the attorney arguing for the winning side, regardless of who they represent.

Table 2. Substantive legitimacy comparisons, male and female participants

Figure 2. Mean differences in participant feelings of substantive legitimacy toward the courts after reading about a sexual harassment decision. Male participants are on the left and female participants are on the right.

The sole exception is among female participants, where, when a female attorney represents an anti-feminist interest and wins, we see a legitimizing effect. Female participants have higher feelings of substantive legitimacy when a female attorney represents an anti-feminist position and wins compared to when a male attorney does, contrary to our expectations. This could indicate that for women, seeing another woman argue in favor of an employer accused of harassment signals something about the veracity and credibility of the claims made by the accuser. In other words, if a female attorney is arguing in favor of an employer, other women may take that as a signal that the original accusation was not credible or made in good faith.

In all other cases, we find no significant within-gender differences in participants’ views of male or female attorneys and therefore find no support for our Hypotheses 3 and 4.Footnote 18 These results further demonstrate that participant gender is not driving our null results for Hypotheses 1 and 2. Or, put differently, our results for Hypotheses 1 and 2 are the result of both men and women being largely unmoved by attorney gender, rather than men and women reacting to attorney gender differently and effectively cancelling each other out. Instead, it appears that attorney gender simply does not influence views of substantive legitimacy for the courts (in most instances) compared to how they do for other branches of government.

It is important to note that both male and female respondents have higher feelings of substantive legitimacy for the courts when they reach feminist decisions than anti-feminist decisions. So, while there is not much variation of substantive legitimacy by attorney gender, the outcome of the case matters and influences views of the courts. Our results show that participants perceive the courts as more substantively legitimate when they reach feminist decisions. These feelings are significantly decreased if the courts reach anti-feminist results.

Results: Procedural Legitimacy

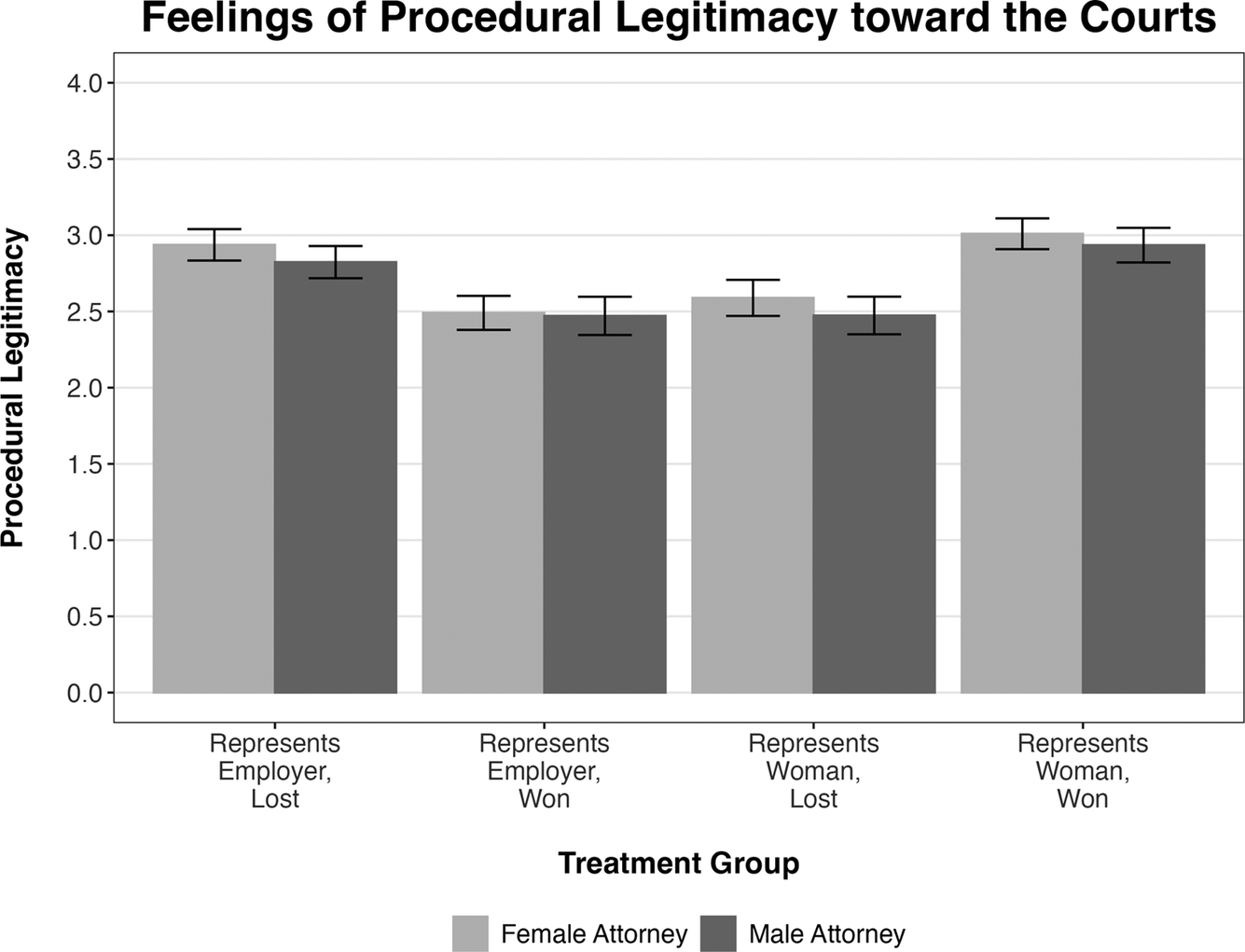

Shifting our attention to procedural legitimacy, Figure 3 provides participants’ feelings of procedural fairness toward the courts across our four treatment groups. Again, we utilize a four-point composite scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of legitimacy.Footnote 19

Figure 3. Mean differences in participant feelings of procedural legitimacy toward the courts after reading about a sexual harassment decision.

Here, we find that, similar to feelings of substantive legitimacy, there are no significant differences in participants’ feelings of procedural legitimacy based on attorney gender.Footnote 20 Participants exhibit similar levels of perceived fairness regardless of whether a male or female attorney represents an anti-feminist interest and wins, represents an anti-feminist interest and loses, represents a feminist interest and wins, or represents a feminist interest and loses. These results are contrary to our expectations for Hypothesis 7 (increased procedural legitimacy when a female attorney successfully argues a feminist or anti-feminist position compared to a male attorney) and Hypothesis 8 (decreased procedural legitimacy when a female attorney unsuccessfully argues a case compared to a male attorney). As such, we do not find support for Hypotheses 7 and 8. This suggests that when determining whether the judiciary acted in a fair manner with respect to specific cases, individuals might not take advocates’ identities and successes into account.

Discussion

Ultimately, our results suggest an attorney’s gender rarely shifts public views of judicial legitimacy. From a substantive perspective, we generally found that female attorneys did not shift the needle of public opinion all that much. While our respondents did seem to have a preferred outcome (ranking cases where accused employers lost as more legitimate), it mattered little who served as the face of these arguments. For issues such as sexual harassment, where there is a presumed victim and victimizer, the public seems to have a preconceived idea of what the “correct” outcome is. The biggest driver of people’s assessment of legitimacy is whether that correct outcome occurred. Importantly, however, we did find one instance where female attorneys did legitimize an anti-feminist outcome. For female respondents, seeing a female attorney successfully argue in favor of an accused sexual harasser made the outcome more palatable than when a man made the same argument. As we speculated in the preceding section, one possible explanation for this finding is that seeing another woman questioning or fighting against a victim of sexual harassment may signal (rightly or wrongly) that the victim’s claims are dubious or otherwise unfounded. This might be an especially meaningful cue to women, who could be more likely to express backlash against unfounded claims of harassment, because they know that such claims are often used as a cudgel to question women who have experienced harassment at the hands of their employers. Ultimately, however, we can only speculate on this point, and more research is needed to fully unpack the underpinnings of this particular relationship.

While we found one notable instance where attorney gender did seem to shape substantive legitimacy, in general, we did not find much of an effect. This differs from legislative contexts where women’s inclusion more broadly seems to legitimize anti-feminist outcomes (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Why does this effect seem more constrained in the context of attorneys and judicial outcomes? One potential reason might be the way people react to court cases. Though the legal process itself is complex, most people do not learn about cases’ complexities and instead only learn about the outcome, typically through the media’s lens (Zilis Reference Zilis2015). Media coverage often provides cues such as judicial partisanship, legal actors’ identity characteristics, and identifying winners and losers to help people react to decisions (Zilis Reference Zilis2021). Such framing mirrors the “game frame” approach used when covering other institutions (Hitt and Searles Reference Hitt and Searles2018), but the end result is wholly different, because people still tend to accept the ruling and the processes used to reach it, even if they disagree with the decision (Gibson Reference Gibson, Bornstein and Tomkins2015). That is, people learn about decisions and respond to them, but their responses do not necessarily shake their confidence in the judiciary. Consequently, gender cues might be interesting but not determinative in these particular situations. Alternatively, in institutions that lack a reservoir of goodwill, the public needs help deciding whether or not to accept outcomes and processes, and gender cues are particularly useful for that sorting. Ultimately, additional research should be conducted with different issue areas and more direct legislative comparisons to fully understand these dynamics.

From a procedural perspective, we found virtually no evidence that attorney gender mattered for respondent evaluations of whether the legal process that decided a case was fair. This again differs from the legislative context, where women’s inclusion generally appears to foster a greater sense of confidence in the decision-making process (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019; Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming). This difference leads us to ask again what makes the judiciary distinct and why findings from legislatures do not appear to port over. We believe the answer lies with the unique nature of judiciary, particularly public belief in its ability to be principled, fair, and impartial. Indeed, research suggests the public trusts the judiciary more than any other political institution, and their belief in judicial legitimacy is enduring and difficult to move (Armaly and Enders Reference Armaly and Enders2022), at least partially because people know little about the judiciary and thus default to the trusting position they learned to take as children (Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003; Zilis Reference Zilis2015). In other words, the public perceives the judiciary is working under a fair and neutral process. Because such processes are already perceived to be working as intended in a fair way, there might be less room for gender to move the needle of public opinion.

Legislatures, in contrast, do not enjoy the same procedural reputation with the public. Research on public opinion finds that when Americans are asked to evaluate the process used by Congress and state legislatures, for example, they offer dismal assessments and report believing the process is largely broken (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse Reference Hibbing and Theiss-Morse2002; Stauffer Reference StaufferForthcoming). This might offer more room for women’s inclusion to make a difference, as the public perceives there to be more room and need for improvement in the realm of legislative process. Moreover, the nature of the legislature just might seem different to Americans. Where the courts are expected to be neutral, no such expectation exists for the legislature. Indeed, the legislature is supposed to actively advocate for groups and interests in ways the courts are not. This difference may simply create a different baseline expectation for how identity comes into play across these different branches of government. Legislative politics also tends to receive more news coverage, which may further set public expectations about the process while also making them feel more familiar with this branch of government compared to the courts.

Conclusion

When Lisa Bloom signed on to represent Harvey Weinstein, the goal was for her presence to legitimize arguments made on Weinstein’s behalf and to signal that any judgment in his favor was valid. She proposed that she could strategically use her gender to legitimize a set of arguments and an eventual outcome that clearly cut against the interests of women. Weinstein is far from the only client to deploy such tactics; consider, for example, that five Canadian hockey players accused of assaulting a young woman made their female attorneys the face of their defense during their very public 2025 trial (Strang and Robson Reference Strang and Robson2025). In this paper, we sought to examine whether such strategies actually work. Using a survey experiment, we asked whether the gender of attorneys representing feminist and anti-feminist interests influenced the degree to which the public viewed the substantive and procedural legitimacy of the courts. For the most part, we found that contrary to our expectations, attorney gender was generally unrelated to how the public evaluated the courts. In other words, it appears the “face” of a particular argument matters less than the outcome the court reaches. While women’s inclusion may broadly legitimize anti-feminist outcomes in some instances (i.e., Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019), our findings suggest that in the context of the courts, the gender identity of the attorney representing a particular argument or group plays little role in shaping the legitimacy of judicial processes or the outcomes of specific cases. This could be because, unlike legislative contexts, citizens idealize courts that are neutral arbiters rather than advocates for particular groups or causes.

While our findings suggest that women attorneys have little influence on the procedural and substantive legitimacy of court cases, there was one very notable exception: when female attorneys successfully represent anti-feminist interests, women participants were more likely to see the process as fair and unbiased. In such situations, it appears that when the courts rule against women, the means by which these rulings are achieved is viewed as less biased and more neutral. This is perhaps not surprising, given that the public broadly believes that institutions built on merit, like nominations-based courts, are inherently fair and unbiased (Goelzhauser Reference Goelzhauser2016), but it is concerning. This finding implies that when women represent anti-feminist interests, the public perceives the process as less biased than if a male attorney took the same position. Given the structural realities of institutions and the continued exclusion of women from positions of power (Arrington Reference Arrington2021), such legitimization may artificially prop up institutions that are, in fact, biased. We hope that future work continues to examine this particularly interesting result.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X25100500.

Acknowledgments

Originally prepared for the 2023 Annual Meetings of the Southern and Midwestern Political Science Associations. We thank Ryan Black, Christina Boyd, Morgan Hazelton, Rachael Hinkle, Alyx Mark, Kirsten Widner, and the Law and Courts Women’s Writing Group for their help on this project.

Statements and declarations

The authors declare no competing interests related to this research. This research was reviewed by the institutional review boards at Michigan State University and the University of South Carolina and is pre-registered through As Predicted, see https://aspredicted.org/HWN_J59.