Language is key to the identity and meaning of the Latin refrain song, delineating the communities for whom Latin is a shared language of education, devotion, and communication. In the previous chapter I explored the mobility and memorability of refrains, showing how text and music travel from liturgy to song, and among songs, and circulate by both written and unwritten means. Importantly, these itinerant refrains are all Latin. The Latinity of the refrain song fosters its mobility and wide-reaching transmission, the shared language of the church and its texts making it possible for disparate communities and institutions to adopt the refrain song for their own purposes or create entirely new devotional songs.Footnote 1 Yet these communities of clerics, monks, and students learned Latin as a second language; their first language was that of their family, town, and region.Footnote 2 In other words, a vernacular language.

The Latin refrain song reflects the varied vernacular contexts of its composers, poets, and performers chiefly through contrafacture, the sharing of a melody by two or more texts in the same or different languages.Footnote 3 Although contrafacture is not a core feature of medieval Latin song in the same way that it is for the motet or liturgical sequence, for instance, clusters of Latin contrafacts (both pairs of Latin songs, and Latin and vernacular songs) emerge in certain manuscripts, associated with particular poets or narrative works, or emanating from specific milieus.Footnote 4 The refrain in Latin song represents a special formal nexus for contrafacture across language; through contrafacture, refrains repeat across the boundaries not only of individual songs, but also language, time, and place. Although a close relationship between Latin and vernacular refrain forms is often assumed due to the formal parallels between the French rondeau and Latin rondellus, the similarity of form does not necessarily suggest the more intimate relationship implied by contrafacture, which involves the sharing of music as well as formal characteristics. Contrafacture – instances in which music is shared explicitly or implicitly across texts – provides a more nuanced perspective on these oft-cited formal parallels and the ways in which the Latin refrain song was, or was not, influenced by vernacular song and refrain, and vice versa.

In this chapter I explore the refrain as an axis between Latin and vernacular song, focusing on what the concentration of contrafacts in a small number of unique manuscripts reveals concerning the interpenetration of song cultures and their languages across Europe. Reflecting highly localized processes of production and transmission, three manuscripts are at the center of Latin refrain song contrafacture: the late thirteenth-century St-Victor Miscellany, copied in the environs of Paris and its schools; the fourteenth-century Engelberg Codex, copied in an abbey scriptorium in Engelberg, Switzerland; and the late fourteenth-century Red Book of Ossory, originating from the diocese of Ossory in Ireland.Footnote 5 These manuscripts demonstrate limited connections to the broader transmission of Latin song, with few concordances, although the poetry and, when extant, music share numerous formal, stylistic, and thematic features with the wider repertoire of Latin refrain songs.

While the three manuscripts are chronologically and geographically disparate, they are linked by the way their collections of Latin refrain songs are transmitted on the page. In each manuscript, Latin refrain songs are accompanied by scribal rubrics and marginalia that cue the text, form, and music of vernacular song. Before or beside Latin poems, in other words, scribes copied short, lyrical fragments in French, German, and English, transforming intertexts into paratexts and alluding to the sharing of poetic form and music; importantly, these fragments are, in the majority of cases, vernacular refrains that correspond directly to Latin refrains. However, two of the three sources – the St-Victor Miscellany and the Red Book of Ossory – transmit only unnotated songs, while the Engelberg Codex lacks notation for six of its nine marginally annotated songs. Since the practice of contrafacture is rooted in the sharing of melodies, the absence of notation is unsurprising. The vernacular fragments, or refrains, behave in many ways like musical notation; knowledge of the melody attached to a given vernacular text enables the musical realization of the Latin poem. Independently of one another, the St-Victor Miscellany, Engelberg Codex, and Red Book of Ossory treat the Latin and vernacular refrain in similar ways by using a formal component of song to initiate formal links and generate musical meaning in the absence of notation.

Although scribal and textual practices in these manuscripts make musical notation unnecessary, they assume an audience familiar with the melodies of vernacular song and refrain. Contrafacture always signals a layer of meaning accessible only to individuals belonging to communities within which sets of texts, melodies, and contrafacts already circulated; even when scribal paratexts elucidate a particular relationship, the audience still requires prior knowledge of vernacular music, form, and poetry. A singer’s relationship to an individual song in any of the three manuscripts discussed in this chapter would change depending on their familiarity with each work in the contrafact pair, or in some cases, cluster, shaping meaning, interpretation, and ultimately performance.Footnote 6 Moreover, the textual persistence of the vernacular in these collections of Latin song and poetry is a reminder that, however deeply embedded through liturgy and education, Latin was a learned language and always circulated alongside vernacular tongues for the creators, scribes, and singers of the Latin refrain song. The St-Victor Miscellany, Engelberg Codex, and Red Book of Ossory bear witness to the multilinguality of medieval song communities, blurring through the lens of the refrain the linguistic boundaries that often define and divide medieval song repertoires.

Contrafacture and the Latin Refrain Song

What counts as a contrafact? Most often, identification of contrafacts derives from recognition of a shared melodic material by sight or sound. How much must be shared to “count” is part of the question, as is the degree to which the text and its poetic and formal characteristics must also be shared.Footnote 7 The degree of sameness is important in terms of distinguishing between contrafacture and other forms of borrowing and citation, in which music might be shared but other elements such as form are not. Judging sameness is especially challenging for the Latin refrain songs in the three manuscripts at the center of this chapter. Although Latin and vernacular song is textually linked by scribes, music rarely survives, and never for both a Latin song and its vernacular counterpart – the degree of musical correspondence, in other words, is impossible to determine. Situating the process of contrafacture in the refrain, however, offers insight into the formal and, to a degree, poetic parallels between Latin and vernacular works. The refrain creates an expectation of form and poetic structure that fosters a degree of similarity across language.

The potential of the refrain to produce certain formal expectations in the process of contrafacture is a likely factor in its popularity among poets and composers: Latin–vernacular contrafacts cluster decidedly around refrain forms. Of the total number of songs in the Appendix, around 12 percent are part of contrafact pairs or families; this compares to roughly 8 percent of all medieval Latin song being identified as contrafacts, of which over 4 percent represent refrain forms.Footnote 8 Refrain-form songs unquestionably participate in contrafacture more often than non-refrain forms. This can partially be attributed to the weightiness of refrains. Although typically representing only a small portion of text, the refrain carries a great deal of information. Refrains convey something about form, namely the presence of repetitive structures, and in many cases the poetry and musical settings of refrains mirror or anticipate those of surrounding strophes; this is certainly the case for the rondellus. The refrain is also a memorable part of a song, perhaps more so than its incipit. As illustrated in the previous chapter, Latin refrains were both constructed from familiar texts and circulated among songs and communities; through different means, the French refrain also circulated among genres and contexts, marked off as distinctive, recognizable, and memorable. Refrains offered something special to scribes and singers – a unit of text (and in some cases music) rich with potential meaning as it repeats within and across song and language.

In the retexting of refrains, meaning is not only transmitted, but shared between two or more songs, knowledge of each work in a contrafact complex informing the understanding of the other(s). With contrafacture, cross-song resonances are always possible, although resonances vary depending on the access a scribe, singer, or listeners has to all the works in a contrafact network and the order in which they are exposed to each work.Footnote 9 For contrafacts lacking textual cues or markers, it is possible to be unaware of relationships to other works via the melody and form. When contrafacture is inscribed on the page, however, an immediate visual, textual, and aural connection is engendered that persists for each new user of the manuscript. Even if – as for modern scholars – the songs cued in rubrics and the margins are unfamiliar, the sensation of hearing more than one song is nevertheless produced.Footnote 10 Moreover, when cued songs are unknown, the new texts and, when available, musical settings, allow us to extend our hearing into this lacuna, however imperfectly – the exchange of information goes in both directions. In our trio of manuscripts, this bidirectional flow enables glimpses into, for instance, repertoires of German and English rondeaux, as well as the early history of certain French refrains.

One well-examined resonance between contrafacts relates to poetic register, and specifically between sacred and secular texts. Contrafacture can enable the implicit or explicit conversion of secular texts toward devotional purposes, as was the case for Gautier de Coinci’s widely transmitted Miracles de Nostre Dame.Footnote 11 By extension, secular vernacular texts can be replaced by pious Latin texts, further magnifying the process of conversion not only by thematic redirection, but also by linguistic change. This has remained a frequent interpretation for the Latin songs of the St-Victor Miscellany, Engelberg Codex, and Red Book of Ossory. However, although the Latin song poems they transmit are entirely devotional, the vernacular songs with which they are associated are not so clearly secular, as I discuss later in this chapter. While the textualization of vernacular song may be interpreted as confirmation of, and emphasis on, the textual conversion from secular to sacred, vernacular to Latin, in these three manuscripts this is only one possibility, and not a fully convincing one. Instead, the regularity and persistence of the vernacular alongside Latin refrain song contrafacts ensures that works are repeatedly read and heard against one another in a way that suggests a continuing discourse rather than a moment of conversion.

Finally, the textual cues and markers found in these three manuscripts are rare among medieval song sources more generally.Footnote 12 In the case of Latin–vernacular contrafacts, cueing happens almost exclusively in the absence of music for one or both works in the contrafact pair, and is overwhelmingly concentrated in the witnesses of the St-Victor Miscellany, Engelberg Codex, and Red Book of Ossory.Footnote 13 Scribal paratexts indicating contrafacture represent an exceptional rather than quotidian practice. Yet the highly localized songs and scribal habits in these three sources simultaneously speak beyond their disparate points of origin to a trans-European interest in the refrain as a point of formal contact between Latin and vernacular song repertoires. Their parallel treatment of the relationship between Latin and vernacular song attests to the agency of refrains and refrain forms in larger cultural discourses around song, language, and meaning. In what follows, I examine each manuscript in turn, beginning with the St-Victor Miscellany in the late thirteenth century and ending with the Red Book of Ossory in the fourteenth century, exploring how song and refrain interact on the page and the implications of this for our understanding of Latin as well as vernacular song and refrain throughout medieval Europe.

French Refrains as Rubrics in a Parisian Miscellany

The earliest of the three sources for Latin contrafacts of vernacular refrain songs, the St-Victor Miscellany, dates from after 1289, a date provided by the poetry copied in its final folios alongside epistolatory materials – letters – pertaining in many cases to the abbey school of St-Denis, its teachers, and its students.Footnote 14 Rather than organized according to type, Latin and bilingual (Latin, French, and Greek) poems and Latin letters alternate freely, with individual items numbered sequentially in the margins by a later hand. While the letters deal with more practical matters than the poems, thematic links do appear, as with references across texts to particular feast days (notably St. Nicholas, a patron saint of students). The collection of verse and epistolary materials in the Miscellany suggests a compiler working in a milieu that was multilingual and intellectual. Several of the poems include words, lines, or partial strophes in French and Greek and details in the letters point to the figure of a grammar school master, capable, among other things, of citing Horace.Footnote 15

While notation is neither included nor was space left for its addition, the musical identity of the Latin poems in the St-Victor Miscellany has long been acknowledged. In part, this is due to the nature of the poems themselves as rithmi, which conveys a degree of inherent musicality and performance. A more revealing feature is the presence of French refrains in the form of rubrics, frequently accompanied by a brief Latin phrase that describes the relationship between the refrain and subsequent text: “contra in latino” (“conversely in Latin”). Identified by Robert Falck as “a kind of ‘prehistory’ for the term contrafactum,” the combination of French refrain and the term “contra” in the rubrics of the Miscellany has established its Latin poems as integral to the tradition of medieval contrafacture, if not as prime examples of the practice.Footnote 16

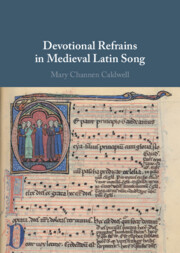

Each rubricated Latin poem in the St-Victor Miscellany, moreover, employs a refrain; poems lacking rubrication invariably lack refrains. It is not only remarkable that these seventeen refrain-form poems are associated with French song; in this case explicit scribal cues for vernacular song uniformly predict the presence of a refrain (see Table 5.1).Footnote 17 As the mise en page makes clear, the French refrains were copied at the same time as the poems they introduce by the same hand (see Figure 5.1). Rather than additions or emendations, the refrains are integral to poems as they uniquely survive in the St-Victor Miscellany. In the layout of the poems, the French refrains are neither marginal nor visually subordinated to the Latin texts. Rather, the layout underscores the importance of the refrains as an interpretive, formal, and musical framework for the Latin poems that follow.

Table 5.1 Poems with refrain rubrics in the St-Victor Miscellany

| Refrain | Incipit of first strophe | Occasion | Rubric | Folio | vdB # | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

| Ecce nobilis | Virgin | Par defaus de leaute que j’ai en amour trove me partire du pais. contra in latino | 177r | vdB 1476 |

| 2 |

| Ecce sanctorum | All Saints’ Day | De tele heure vi la biaute ma dame que ne puis sanz li. contra in latino | 178r | vdB 484 |

| 3 |

| Virgo gemma gracie | Katherine | La tres grant biaute de li ma le cuer du cors ravi. contra in latino | 178r–v | vdB 1205 |

| 4 |

| Ille puerulus jacens cunabulis | Nicholas | Joi te rossignol chantez de sus .i. rain u jardinet m’amie de sus l’ante florie. contra in latino | 178v | vdB 1159 |

| 5 |

| Ecce festum egregii | Denis the Martyr | E jolis cuers se tu t’en vas s’onques m’amas pour dieu ne m’antroblie pas. contra in latino | 181r | vdB 847 |

| 6 | Letare mater ecclesia | Ecce festum beate Katerine | Katherine | Ci aual querez amoureites. contra in latino | 181v | vdB 355 |

| 7 |

| Hic fulgens virtutibus | Nicholas | Je fere mentel taillier cousu de flours, ourle d’amours fourre de violeite. contra in latino | 182r | vdB 1044 |

| 8 |

| Ecce venit insigne | Virgin/Pentecost | Amours amours amours ai qui m’ocient et la nuit et le iour | 183r | vdB 150 |

| 9 |

| Ecce festum nobile | Pentecost | Au bois irai pour cullir la violeite mon ami i trouverai. contra in latino | 183v | vdB 191 |

| 10 |

| Ave, plena gracia | Virgin | Dex quar haiez merci de m’ame si con j’e envers vous mespris. contra | 184v | vdB 488 |

| 11 |

| Universorum orgio | All Saints’ Day | Amez moi douce dame amez, et je fere voz voulentez | 186r | vdB 117 |

| 12 |

| Virgo costi filia | Katherine | Unques mes ne fu seurpris du mal d’amoueites mes or le sui orandroit | 186r–v | vdB 1423 |

| 13 |

| Hic Dei plenus gracia | Nicholas | Unques en amer leaument ne conquis fors que mal talent | 186v | vdB 1420 |

| 14 |

| Pulsa noxe scoria | Pentecost | Honniz soit qui mes ouan beguineite devendra | 187v | vdB 881 |

| 15 |

| Ecce orgium | Pentecost | Bonne amoureite m’a en sa prison pieca | 188r–v | vdB 288 |

| 16 |

| Ecce virginis Marie | Virgin | Dex donnez me joie de ce que jain l’amour a la belle ne puis avoir | 188v | vdB 515 |

| 17 |

| Ille civis Pathere | Nicholas | Rois gentis faites ardoir ces juiis pendre ou escorcher vis | 189r | vdB 1635 |

Figure 5.1 St-Victor Miscellany, fol. 177r, Marie preconio with French refrain and “contra in latino.”

From the perspective of form, the French refrains and the works they signal outside of the Miscellany appear to correspond with the poetic and formal structures of the Latin poetry. To take Marie preconio from Figure 5.1 as a further example, the French refrain serving as its rubric survives in Douce 308 (fol. 214r–v [226r–v]) in the context of a ballette à refrain, a courtly love song.Footnote 18 Comparing the French refrain with the Latin refrain, the mirroring of syllable count and rhyme across languages is readily apparent (pp = proparoxytonic accent):

| Par fate de lëaultei | 7 | a | Marie preconio | 7pp | a |

| Ke j’ai an amors trovei | 7 | a | Serviat cum gaudio | 7pp | a |

| Me partirai dou païx. | 7 | b | Militans Ecclesia. | 7pp | b |

| Due to the lack of loyalty I have found in love, I will leave the region. | May the militant church preserve with joy praise of Mary. |

The same holds true for the strophic material of the ballette à refrain in Douce 308 and Latin poem in the Miscellany: The latter corresponds in syllable count and rhyme scheme with the vernacular song. This refrain concordance is especially helpful due to the inconsistent cueing of the Latin refrain in Marie preconio. Despite a relatively high degree of scribal attention to layout in the poetic assemblage of the St-Victor Miscellany in general, cues for regularly recurring refrains do not always appear. In this case, the alternation of strophes and refrains can be extrapolated from knowledge of the French ballette à refrain.Footnote 19 What the survival of the French refrain in Douce 308 does not provide, however, is a possible musical realization for Marie preconio, since this sole refrain concordance is unnotated.

Of the seventeen refrains preserved in the St-Victor Miscellany, five (including the one just discussed) have concordances as refrains in ballettes à refrain, dits entés, and narratives.Footnote 20 Of these, three survive with notation in at least one source. Two of these notated refrains appear in the early thirteenth-century interpolated Fauvel manuscript attributed to Jehannot de Lescurel, while the third occurs in the late thirteenth-century romance Renart le Nouvel (see Table 5.2).Footnote 21 Given the existence of notated concordances, it is possible to underlay some of the Latin poems to the melodies of French refrains, as scholars have previously attempted.Footnote 22 A parallel transcription of the refrain Ames moi douce dame amez from Fauvel cited in the rubric for Superne matris gaudia appears in Example 5.1; the close relationship between syllable count and rhyme scheme is readily apparent. For this refrain, a musico-poetic insertion in a dit enté attributed to Jehannot de Lescurel and not part of a larger song structure, the only music preserved is that of the refrain itself. Indeed, all three concordant refrains presented with notation survive as refrain melodies alone, serving as insertions into poetic and literary texts (a dit and romance) rather than as part of fixed song forms, such as a ballette à refrain. In the two contexts for which the concordant refrain belongs to a song (in both cases ballettes à refrain in Douce 308), notation is unfortunately lacking.

Table 5.2 Refrain concordances in the St-Victor Miscellany

| French refrain incipit in the St-Victor Miscellany | Concordances | Date | Context | Notated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Par defaus de leaute | Douce 308, 214r–v (226r–v) and 225r (236r) | after 1309 | Ballette à refrain | No |

| Joi te rossignol chantez | Fauvel, 61r | 1314–1317 |

| Yes |

| Ci aual querez amoureites | Paris fr. 23111, 212v | late 13th | Le Livre d’amoretes | No |

| Paris lat. 13091, 151r | 1380–1400 | |||

| Amez moi douce dame | Fauvel, 61v | 1314–1317 |

| Yes |

| Unques en amer leaument | Douce 308, 227v (238v) | after 1309 | Ballette à refrain | No |

| Paris fr. 372, 34v | ca. 1292 | Renart le Nouvel | Yes | |

| Paris fr. 1593, 33v (34v) | ca. 1290 | |||

| Trouv W, 147v | after 1288 | |||

| Paris fr. 1581, 33v | late 13th | No |

Example 5.1 Underlay of Superne matris gaudia to Amez moi douce dame (St-Victor Miscellany, fol. 186r and Fauvel, fol. 61v)

Consequently, the music for the refrains alone survives as a clue to the melodic realization of certain Latin poems in the St-Victor Miscellany. In each case, the refrain’s music can nevertheless be underlaid to the entirety of the Latin poem due to the shared scansion between strophes and refrain. Following Grocheio’s description of a rotundellus, “the parts of which do not have a melody different from the melody of the response or refrain,” for these Latin poems with notated refrain concordances, the music of the whole could be derived solely from the refrain.Footnote 23 In the case of the three songs with extant melodic material for the French refrains, Superne matris gaudia, Nicholai sollempnio, and Sancti Nicholai, the regular scansion and form of each poem allows for the reuse of the refrain’s melody throughout; in the other poems with refrain rubrics but without surviving musical material, the scansion is varied enough to make such a realization unlikely. In other words, only in certain cases does the music of the French refrain accompany both strophic and refrain material. The survival of notated refrain concordances nevertheless supports interpretation of the French refrain rubrics in the St-Victor Miscellany as musical, as well as formal, cues. Even without notated concordances one could understand the cues as musical – the absence of notation does not necessarily correlate to the absence of music.Footnote 24 Moreover, the refrains themselves rhetorically convey musical performance, repeatedly calling on the church and its community to sing using the imperative and subjunctive forms of verbs including “concinere,” “cantare,” and “pangere” (see Chapter 2 on similar verbiage suggesting musical performance in refrain songs).

Why provide solely refrain-form poems with such explicit cues? It seems unlikely that the other, strophic poems would have lacked a similar life in performance, and there are certainly examples of strophic contrafacts outside of the Miscellany. One answer might be found in the itinerant nature of refrains during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. As Ardis Butterfield notes, the vernacular refrain’s identity as a “small, independent and culturally distinctive [element]” affords it weighty currency in the circulation of medieval music and text. The privileging of the refrain as an epicenter of musical and poetic meaning speaks, too, to the broader context of the intertextual refrain and its citation in clerical and monastic contexts. As Jennifer Saltzstein argues, “vernacular refrains were treated as valued sources of knowledge,” and “the treatment of intertextual refrains in these contexts reveals a preoccupation among clerical writers with the status and authority of the vernacular song tradition, even when measured directly against the authority of the Latin.”Footnote 25 In the St-Victor Miscellany, Latin and vernacular interact explicitly through the refrain, serving as yet another form of intertextual citation and as an acknowledgment of the wider song culture of which Latin song is a part.

The refrain rubrics in the St-Victor Miscellany certainly suggest a poet and/or scribe conversant enough in the culture of vernacular song such that refrains could serve as a musico-poetic shorthand. Given the Parisian milieu of Lescurel, the sole name attached to the refrains copied in the Miscellany – albeit copied more than a quarter of a century later in Fauvel – and the circulation of the other refrains in northern French sources, responsibility for the collection of refrains and Latin contrafacts in the Miscellany probably resides with an individual or community not only affiliated with a pedagogical institution, but with ears tuned to French lyric. This is all the more evident considering the network of refrain concordances in Renart, Le Livre d’amoretes, Douce 308, and the dits of Lescurel in Fauvel that form the core of the refrains cited in the St-Victor Miscellany.Footnote 26

The timeline of these sources for the concordant refrains in the St-Victor Miscellany, however, is notable – none of the refrains is transmitted in any manuscripts earlier than the late thirteenth century. In other words, the rubrics in the St-Victor Miscellany reflect the earliest copying dates for five refrains, and the unique witness for the remaining twelve. What might this reveal about the citational network of refrains in the later thirteenth century? If the refrains were known prior to their inclusion in the rubrics of the St-Victor Miscellany, how and where were they circulating? Conversely, if these refrains were newly created for the Miscellany, through which intermediary texts did they make their way, for instance, into Lescurel’s dits entés or Douce 308?

While these questions may remain unanswerable, the subject matter of the French refrains offers some insight into the milieu of the creator and/or compiler of the poems, as well as the earlier history of refrains otherwise only attested in later sources. Courtly love comprises the principal theme of the refrains on the whole, with the conventional vocabulary of French song and romance fully present. With themes of courtly love amply represented, most of the refrains with and without concordances transmitted in the St-Victor Miscellany would be at home in any of the expected contexts, from song and motet to narrative romance, as evidenced by the list of concordances in Table 5.2. Amid the predominantly love-themed refrains, two stand out for their lack of engagement in this courtly vocabulary. The first, “Honniz soit qui mes ouan beguineite devendra” (“Evil be to her who will now become a beguine”), rubricating Pange cum leticia, references the beguines, and the second, “Rois gentis faites ardoir ces juiis pendre ou escorcher vis” (“Noble king, make the Jews burn, hang, or be skinned alive”), rubricating Laudibus Nicholai, is an alarming invective against Jews. While both appear to be unique, the refrains nevertheless display striking resonances with the broader cultural context of thirteenth-century France and its literary and musical sources.

The first of the two unique refrains curses a woman entering the lay sisterhood of the beguines, a community whose numbers increased dramatically over the course of the thirteenth century before reforms in the early fourteenth century.Footnote 27 With communities across Europe, especially the Low Countries and in major cities such as Paris, beguines received both positive and negative attention from religious and civic institutions and individuals. Beguines (as with other religious figures, especially women) make repeated appearances in medieval French song and poetry, which refer to them in pejorative ways.Footnote 28 The refrain of the motetus in a rondeau-motet in the Chansonnier de Noailles, Ja n’avrés deduit de moi/SECULUM exemplifies one of the more common attitudes toward beguines, situating an anonymous beguine as a hypocrite, only offering her affections after entering the (celibate) lay order:

| Motetus | Ja n’avrés deduit de moi se je ne sui beguine, par la foi ke je vous doi. Ja n’avrés deduit [de moi] se je ne sui beguine. | You will never take your pleasure with me unless I become a Beguine; Take my word for it. You will never take your pleasure with me |

In a similar vein, the refrain in the St-Victor Miscellany focuses not on the hypocrisy of beguines, but on the perceived wrongness of the lay order. Reflecting an attitude of censure often held by clerics and monastics, the inclusion of an anti-beguine refrain in a collection of devotional Latin texts serves as another possible indicator of the institutionally religious, and potentially conservative, milieu of the compiler.

The second of the two non-courtly love refrains, beginning “rois gentis,” expresses a markedly darker sentiment than most contemporary refrains, although not necessarily darker than texts in contemporary genres. Hostility toward Jews akin to what appears in the refrain from the St-Victor Miscellany is scattered throughout medieval French narrative sources, sermons, and numerous other texts. Throughout the thirteenth century in France, under the rule of Louis IX followed by Philip III and Philip IV, Jewish communities experienced increasing antisemitism and violence, culminating in the expulsion of Jews from France in 1306.Footnote 30 However, as far as I am aware, no parallel poem or song exists featuring such strikingly violent language. References to Jews do occur, often in the context of conversion, and the song culture of medieval France included a number of Jewish composers and poets.Footnote 31

I have located a possible model for the language of this violent refrain in an Old French Evangile de l’enfance, an example of a subtype of vernacular religious writing that takes Christ’s infancy as its focus.Footnote 32 Although sources for the Old French Evangile all date from after the turn of the fourteenth century, the origins of the text have been placed in the late thirteenth century, if not earlier.Footnote 33 With a terminus post quem of 1289 for the St-Victor Miscellany, the composition of the Evangile and the Latin poems may be roughly contemporaneous. Significantly, the Evangile de l’enfance includes a passage whose language mirrors (or is mirrored by?) the refrain in the St-Victor Miscellany:

| Evangile de l’enfance | St-Victor Miscellany, fol. 189r |

|

Vivre ne devroit o nous chi, Ansi le doit on crucfïer Pendre ou ardoir ou eschorchier, Car il confront toutes nos loys; Je veul gue il soit mis en crois. | Rois gentis faites ardoir ces juiis pendre ou escorcher vis |

|

He [Jesus] should not live with us here, But we should crucify him Hang him or burn him or skin him Because he is destroying all our laws; I want him to be put on a cross.Footnote 34 | Noble king, make the Jews burn, hang or be skinned alive. |

Both texts list the same horrors – burning, hanging, and flaying. The key difference is the intended recipient of the torture in each context.Footnote 35 In the Evangile de l’enfance, the speaker is a Jew addressing Jesus, while the invectives of the refrain are explicitly directed at Jews. In the Evangile de l’enfance, the anti-Jewish sentiment surrounds the excerpted passage, including in the authorial explanation that directly follows: “this was the first root [cause] | why God had hatred for the Jews.”Footnote 36 In both contexts, then, Jews are ultimately situated in negative terms, whether as the aggressor in the Evangile or object of aggression in the poem. Whatever the relationship between the sources (including the possibility of an unknown intermediary), the shared vocabulary of the two texts undeniably participates in the deeply anti-Semitic culture of thirteenth-century France.Footnote 37

The refrain rubrics of the St-Victor Miscellany represent a varied, if at times problematic, interpretive frame for the relationship between Latin and vernacular song. Situating the collection of unnotated Latin poems within a deeply bilingual setting, the use of French refrains points not only to the compiler’s or scribe’s familiarity with vernacular song, but their assumption of an audience equally familiar with the vernacular repertoire. With refrains serving as formal and melodic mnemonics for the Latin poems, a collection that is otherwise lacking music is provided with a musical subtext, even if the sound of many of the songs remains inaccessible due to the lack of notated concordances. Yet refrains with and without concordances paint a picture of a working environment for the compiler and/or writer of the poems that is of his time – a complaint about beguines and a brutal cry to arms against Jews place the poetry firmly within the cultural setting of late thirteenth-century France. Finally, refrain-form poems comprise only part of the poetic contents of the Miscellany, yet these are the sole works whose ties to vernacular song are made visually and textually explicit. The refrains of the St-Victor Miscellany bear witness to the multivalence of the refrain, bridging language and register, and cueing music and form.

German Song in the Margins in the Engelberg Codex

The late fourteenth-century/early fifteenth-century service book and troper for the Benedictine Abbey of Engelberg, the Engelberg Codex, sits at a sharp chronological, geographical, and repertorial remove from the St-Victor Miscellany.Footnote 38 Alongside polyphonic works, tropes of Office and Mass chants, and an Easter play, numerous Latin songs are preserved in this unique source produced by and for the use of a single community in Switzerland.Footnote 39 Also particular to the Engelberg Codex is its transmission of German-texted works, both liturgical and extraliturgical, including several German contrafacts of hymns, sequences, and songs.Footnote 40 In addition to offering insight into late medieval troping practices, the Engelberg Codex also serves as a witness to the use of the vernacular within and alongside the liturgy. Although the liturgical orientation of this Swiss Codex contrasts with the intellectual milieu of the St-Victor Miscellany, the contents of both manuscripts reveal an interest in multilinguality and song.

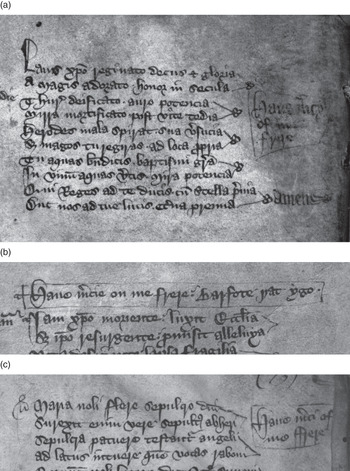

Refrain songs are among the varied works copied into the twelfth and final gathering of the Codex (fol. 168r–182v), a grab bag in terms of genre and function.Footnote 41 Since the gathering existed independently before being compiled with the other eleven, trimming of the edges resulted in the loss of some textual information. Specifically, for nine unique Latin songs with refrains – eight of which are rondelli – marginal notes added by two different scribes have been partially lost. What remains are jotted fragments of German lyric, included in Table 5.3 along with corresponding Latin poems, refrains, rubrics, and occasions.Footnote 42

Table 5.3 Engelberg Codex, refrain songs with marginal German annotations

| Incipit | Refrain | Occasion | Rubric | Marginal German lyric | Folio | Notation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Veni sancte spiritus |

| Pentecost | De spiritu sancto | Sol mi [ ] dienst sin | 168r | YES |

| 2 | O virgo pelle |

| Marian | De sancta Maria | Dissen ich [ ] vs | 168r–v | NO |

| 3 | Pusillus nobis nascitur |

| Nativity | De nativitate domini | [ ]kùnd | 168v | NO |

| 4 | Flore vernat |

| John the Evangelist | De Iohanne ewangelista | [ ]ten sehen []cherli | 168v | YES |

| 5 | O stirpe regis filia |

| Marian | De sancta Maria | [ ] dich alle [ ] so bin ich | 168v | NO |

| 6 | Salve virgo Margaretha |

| St. Margaret | De sancta Margaretha | Ein wild [ ]vf [ ] gen | 169r | NO |

| 7 | Congaudent omnes angeli |

| St. Michael | De angelis | [ ] wilduang [ ] f genaden | 169v | YES |

| 8 | Ave stella maris Maria |

| Marian | De sancta Maria | [ ] mimpt mir [ ]l der frœd | 169v | NO |

| 9 | Nato celorum Domino |

| Nativity | De nativitate domini conductus | [ ] blᵫndes [ ]s aller selikeit | 175v–176r | NO |

In addition to belonging to a single gathering, the nine songs appear within the space of relatively few folios (168r–176r), with the rondelli (songs 1–8) copied almost back-to-back. Only three songs survive with notation, a not uncommon situation for this codex. For each song, visible stave lines indicate a single melodic line, with the residuum copied below. With respect to musical style, the eight rondelli are unusual among Latin refrain songs since they feature melismatic passages, typically at the beginning and end of verse lines.Footnote 43 Even for the unnotated songs, text underlay suggests similar melismatic treatments. For the only strophic+refrain song, Nato celorum Domino, the textual underlay of this unnotated song suggests a syllabic rather than melismatic setting. Form, rubrication, and, in nearly all cases, musical style mark these songs as different from others within the Engelberg Codex and among the wider repertoire of Latin refrain songs.

Yet, these songs are still devotional; Latin rubrics indicating feast or saint introduce all nine songs. The poems cover conventional topics for refrain songs (Christmas, Pentecost, the Virgin), with the addition of two unusual saints for the repertoire, Margaret and Michael; neither saint appears with any regularity in medieval Latin song, and both must have been of special interest to the community in Engelberg. While the Latin poems are unique, several rework liturgical chant texts, including sequences and hymns preserved elsewhere in the Engelberg Codex. Most notable is Flore vernat virginali for John the Evangelist, which shares its incipit and textual material with a sequence of the same name appearing earlier in the manuscript.Footnote 44 Other refrain songs in the Engelberg Codex similarly appear to be reworkings, although less closely tied to their models than Flore vernat virginali. These include Veni sancte spiritus [B] and Ave stella maris Maria, both of which borrow from well-known chants, namely a Pentecost sequence and a Marian hymn, respectively.

Notably, the melodies for both sequence and song versions of Flore vernat virginali survive in the Engelberg Codex, and they are markedly different. The song reworks only the text, not the musical setting. Instead, the melody for the refrain song appears to derive from outside of the manuscript, cued by means of a marginal note made unintelligible by trimming undertaken when the gathering was joined with the previous eleven to form the current Engelberg Codex (see Figure 5.2).Footnote 45 The German text as it appears here is “[]ten sehen[]cherli,” which offers little in terms of poetic meaning and has no witnesses outside of the Engelberg Codex. Nevertheless, the marginal notes in this gathering of refrain-form songs suggest that they were modeled on the melodies and perhaps also poetic forms of vernacular songs – in this case, chiefly German songs that take the poetic and musical form of a rondeau (ABaAabAB). Certain of the refrain song contrafacts in the Engelberg Codex, in other words, are doubly constructed from borrowed material – text from liturgical chant and music from vernacular song. This may explain, too, the more unusual musical, melismatic style for the rondelli in the Codex compared to other notated rondelli, such as those in the thirteenth-century F and Tours 927; earlier rondelli are generally not contrafacts, while these later fourteenth-century rondelli appear to be musically related to German song.

Figure 5.2 Engelberg Codex, fol. 168v, Flore vernat virginali with marginal lyric.

Although the nine pairs of German lyric and Latin contrafacts are unique to the Engelberg Codex, the existence of these rondelli has not escaped the notice of scholars seeking German counterparts to the French formes fixes. Indeed, the contrafacts in the Engelberg Codex have long been positioned as early witnesses to a tradition of German song modeled after northern French forms.Footnote 46 Notably, the relationship between Latin and German rondeau-form songs occurs in at least one other source that makes the relationship between the two languages explicit, albeit with no surviving music: the Erfurt Codex.Footnote 47 A fourteenth-century manuscript originating in England before being owned and annotated by rector Johannes Barba of the St. Katherine Chapel at Aachen’s collegiate church of St. Mary, the Erfurt Codex transmits a series of unnotated German songs with similarly unnotated Latin contrafacts in rondeau form all added by Barba. Rubrication cues the relationship, with Latin poems preceded by rubrics such as “Kantilena Latinalis super isto” (referring to the German poem just prior) or “Sequitur kantilena primo in Teutonico, post in Latino.” All told, the Erfurt Codex transmits six German rondeaux with five Latin contrafacts, in addition to an assortment of poetic texts in both languages.Footnote 48 While the Erfurt Codex contains no musical notation, its pairing of German and Latin rondeaux provides a fuller picture of the diglossic tradition gestured to in the marginal inclusion of German lyrical fragments in the Engelberg Codex. Moreover, the existence of the full text in both languages in Barba’s pairings sheds light on the nature of the poetry itself; akin to the Engelberg Codex, the Latin poems are chiefly devotional in register, while the German songs reflect a worldlier outlook. The phrasing and position of the songs in the manuscript is also notable; the German poems provide the models for the Latin poems, the latter in each case designated “super,” “to the tune of,” the former.Footnote 49

The existence of Barba’s bilingual poetic addendum, however, does not offer insight into the specific German songs cued in the margins of the Engelberg Codex. For the most part, scholars have lamented the fragmentary nature of the German lyrics in the margins. Even the interpretation of these fragments is subject to debate; readings of the marginal lyrics vary considerably, although general consensus is that the German texts from which they are derived are unique.Footnote 50

One promising avenue has emerged in a study attempting to locate German lyrics cited in the early fifteenth-century Limburg Chronicle attributed to Tilemann Elhen von Wolfhagen, in which Gisela Kornrumpf outlines a network of largely unnotated German rondeaux surviving from the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. With the marginal lyrics preserved in the Engelberg Codex and the more complete texts in the Erfurt Codex among her examples, Kornrumpf has uncovered a concordance for three of the German marginalia in the Engelberg Codex, those lyrical fragments attached to Salve virgo Margaretha, Congaudent omnes angeli, and O virgo pelle (see Table 5.3). With respect to the first two songs, Kornrumpf makes the case that they share the same German lyric, linking “Ein wild []vf [] gen” beside Salve virgo Margaretha to “[] wilduang [] f genaden” beside Congaudent omnes angeli. Kornrumpf identifies a possible match with this German lyric in a rondeau transmitted as text only in Munich cgm. 1113, Ein wildfanch auf genad.Footnote 51 As she demonstrates, the extant poetry of the German rondeau aligns neatly with that of the Latin rondelli in the Engelberg Codex, making her identification of the marginal lyric highly possible. Consequently, it seems that the German song lyrics familiar to the scribes of the Engelberg Codex circulated beyond the immediate milieu of the manuscript. One could also move in the other direction and interpret the musical setting of Congaudent omnes angeli as preserving the melody of an otherwise unnotated German song.

More directly connecting to Tilemann’s Chronicle is the refrain song O virgo pelle, its accompanying lyrical fragment reading, according to Kornrumpf, as “<Des?> | dispa< … > | ich vs(g)< … >.”Footnote 52 What this new interpretation of the German text affords is a link to a lyric cited in the Limburg Chronicle, beginning “Des dipans bin ich ußgezalt.”Footnote 53 As Kornrumpf argues, the texts in the Limburg Chronicle (sung by the “Barfüßers vom Main”) may be refrains of longer German rondeaux.Footnote 54 In this case, the marginal lyric beside O virgo pelle could provide confirmation that the lyric in the Chronicle is, in fact, a refrain. Conversely, a concordance for a second of the German songs cited in the Engelberg Codex points to the borrowing of musical and poetic materials in circulation more widely, either in writing or orally. As these examples illustrate, information flows not only from the vernacular to Latin, but from Latin to German, painting a fuller picture not only of Latin song culture in medieval monasteries, but of a multilingual song culture.

To sum up, of the nine unique Latin contrafacts in the Engelberg Codex, at least three may be modeled after German rondeaux surviving in other sources compiled in German-speaking areas, paralleling similar practices found in contemporary, albeit unnotated, sources. The lack of notation in these other sources, however, sets the Engelberg Codex apart. While the existence of the lyrics elsewhere affirms the wide dissemination of the German songs, their inscription in the Engelberg Codex means that their music may also have survived, retexted with devotional Latin poetry. The engagement of the scribes of the Engelberg Codex with German songs in wider circulation also speaks to the integral bilingualism of the manuscript. As in the St-Victor Miscellany, in which Latin and French freely rub shoulders and complement one another, German and Latin continually inform one another throughout the Engelberg Codex. With movement from Latin to German, and vice versa, represented, the manuscript offers a window into the linguistic fluidity of high medieval musical life and, indeed, its song culture.

The gathering of refrain-form Latin songs with their marginal German lyrical citations further situates the refrain as a node through which linguistic transformations could take place. With the identification of at least three of the lyrical fragments as likely German rondeaux, it is clear that the refrain was not only the most memorable part of the song (and therefore provided the richest textual and visual clue), but also that it encoded melodic information. Kornrumpf in fact has suggested that the marginal lyrics were cues for the music scribe, indicating solely through the incipit of German refrains the melodic structure to which the new Latin poems were to be fitted.Footnote 55 This would certainly go a far way toward explaining why these songs required notation in the first place, since it is often the case that the citation of a musical model eliminates the need for musical notation. However, a degree of inconsistency obtains throughout the Engelberg Codex with respect to how contrafacts were inscribed. In the case of German reworkings (or more accurately, translations) of hymns and sequences, at times text alone is preserved with rubrics pointing to the textual and musical model (i.e. “Ut queant laxis verbo et melodia,” fol. 10r); at other times, both rubric and music appear (as in “Sicut Letabundus verbo et melodia,” fol. 89r).Footnote 56 In other words, the scribes of the Engelberg Codex did not preclude notation for works they probably knew (such as the sequence beginning Letabundus). Instead, as in the refrain-form songs in the final gathering, the scribes doubled up on information for works that crossed linguistic boundaries, including rubrics, marginal notes, and musical notation. Regardless of the reasons for the seeming overlap between textual and musical information, the marginal annotations of Latin refrain songs in the Engelberg Codex provide further testimony to the encoding of melodic and poetic meaning in refrains, however fragmentary and brief their inscription and accidental their survival.

Multilinguality in the Red Book of Ossory

Approximately 1,000 miles away during the same decades that the scriptorium at Engelberg actively copied and compiled the Engelberg Codex, a different group of scribes began work on what would become known as the “Red Book of Ossory.” Copied from the last quarter of the fourteenth century and into the fifteenth century, the Red Book of Ossory preserves a variety of materials, including documents pertaining to the Ossorian diocese, chapters of the Magna Carta, various statutes and ordinances, proverbs, and a collection of sixty largely unique, unnotated, devotional Latin poems.Footnote 57 Although predominantly Latin, the manuscript as a whole is multilingual, with contents in French and, to a lesser degree, English. Due to its wide-ranging contents, the Red Book of Ossory has drawn the attention of scholars for over a century; the Latin poems in particular (often dubbed “hymns”) have received frequent mention and were edited in their entirety three times in the early 1970s, in a somewhat bizarre coincidence.Footnote 58

The modern fame of the poems in the Red Book of Ossory derives from two features of the manuscript source: the authorial framing of a textual preface on the first folio of the collection; and the inclusion of “snatches” of lyric in English, French, and in one case Latin, preceding and alongside thirteen of the poems and widely interpreted to be melodic cues (see Table 5.4).Footnote 59 The layered paratexts of the preface and lyrical fragments afford a range of possible interpretations and allude to a dense network of possible allusions (musical and poetic) operating within this fairly large group of poems. Beyond the presence of such textual and poetic materials, the poetry of the Red Book of Ossory finds a place in this book due to the prevalence of refrains: over eighty percent of the poems (forty-nine out of sixty) feature refrains or highly repetitive structures with internal repeats. Of these, just over half (twenty-five) are rondelli, making the Ossorian manuscript one of the largest repositories of rondelli alongside thirteenth-century sources such as F and Tours 927.Footnote 60 Yet, akin to the German milieu of the Engelberg Codex, the context for these Latin poems lies at a linguistic and geographical remove from the French forme fixe tradition, signaled by the inclusion of English lyrical cues and the Ossorian origins of the manuscript and its compilation. With its formal and material linking of devotional Latin poetry, refrains, and vernacular lyric, the Red Book of Ossory reflects an intertextual culture of song production and performance, one in which the refrain once again serves as an axis for linguistic, musical, and poetic exchange.

Table 5.4 Poems with rubrics or marginal annotations (repeated rubrics in bold) in the Red Book of Ossory

| Incipit | Refrain | Occasion | Rubric or marginal note | Language of rubric | Folio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Laus Christo regi nato | – | Epiphany | Haue mercy of me frere | English | 70v |

| 2 | Peperit virgo | – | Nativity | Mayde y[n] the moore [l]ay | English | 71r |

| 3 | Succurre mater Christi | – | Marian |

| English | 71v |

| 4 | Jhesu lux vera seculi | Yes | Christ |

| French | 71v |

| 5 | Jam Christo moriente | – | Easter |

| English | 71v |

| 6 | Dies ista gaudii | Yes | Easter |

| English | 72r |

| 7 | Plangentis Cristi uulnera | Yes | Easter | En Christi fit memoria | Latin | 72r |

| 8 | Resurgenti cum gloria | Yes | Easter | Haue god day my lemon &c | English | 72v |

| 9 | Maria noli flere | – | Easter | Haue merci of me frere | English | 73r |

| 10 | Verum est quod legi satis plene | – | Moral / Judgment Day |

| English | 73v |

| 11 | Regem adoremus | Yes | Nativity |

| English | 74r |

| 12 | Vale mater virgo pura | – | Marian / Presentation at the Temple |

| French | 74v |

| 13 | En parit virgo regia | Yes | Nativity | Hey how þo cheualdoures wokes al nyght. | English | 74v |

Unusually for songbooks or gatherings, the collection includes a preface at the foot of the first four poems on fol. 70r (see Figure 5.3 and Chapter 1). In this brief “nota” (as it is rubricated in the manuscript), the songs are identified as the work of an unnamed Bishop of Ossory, who is assumed to be Richard Ledrede based on the approximate dates of copying (1360s) and of his tenure as bishop (1317–1360):Footnote 61

Be advised, reader, that the Bishop of Ossory has made these songs for the vicars of the cathedral church, for the priests, and for his clerks, to be sung on the important holidays and at celebrations in order that their throats and mouths, consecrated to God, may not be polluted by songs that are lewd, secular, and associated with the theatre, and, since they are singers, let them provide themselves with suitable tunes according to what the poems require.Footnote 62

The preface attributes the making (“fecit”) of the songs to the bishop for the benefit of his clergy; it continues by decrying the singing of lewd, secular songs, thereby positioning the collected songs as a kind of pious entertainment for “great feasts.”Footnote 63 The final phrase has proved the most interesting for scholars due to its resonance with the largely vernacular cues that appear throughout the song collection: “since they are singers, let them provide themselves with suitable tunes [notes] according to what the poems require” (“et cum sint cantatores prouideant sibi de notis conuenientibus secundum quod dictamina requirunt”).Footnote 64 With this reference to the music of the poems in mind, the lyrical fragments interspersed throughout have thus been understood as references to the melodies suited to the poems.

Figure 5.3 Red Book of Ossory, fol. 70r, preface.

What often seems to be missed, however, is the preface’s abnegation of responsibility to supply the melodies “required” by the poems. Most frequently, attempts to grapple with the poems focus on linking the Latin texts attributed to Ledrede to the fragmentary citation of vernacular lyrics. Consequently, one argument sees the inclusion of vernacular snippets as examples of the kinds of lewd and secular song Ledrede aimed to erase from the mouths of his clergy; another argument sees the situation instead as one of compromise, with Ledrede acknowledging the popularity of vernacular song and offering pious textual substitutes for the melodies his clergy enjoyed.Footnote 65 However, the preface seems to suggest that the bishop himself is not overly concerned with the melodies, and instead expects singers to provide “suitable” ones themselves. The implications of this shift in the interpretation of the preface concern the nature of the relationship between the song citations and devotional Latin poems, and the question of the users of, and audience for, the songs in their material form.

Although Ledrede is rhetorically framed in scholarship as the author of the songs in the Red Book of Ossory, and this is conflated with the work of scribes and/or copyists, the extent of his responsibility for the writing and compilation of the songs is unknown (and, indeed, the poems may have been compiled posthumously).Footnote 66 Several of the Latin texts, moreover, are not original but instead are extracted from a longer work by Walter of Wimborne.Footnote 67 At least three scribal hands – none of which are likely to be that of Ledrede himself – contributed to the copying of the folios, with poems written tidily, albeit with errors, in two neat columns with plenty of empty space; the preface was added by yet another hand. The mise en page immediately signals the poetic contents by means of blocks of text demarcating each work, and within each block the use of a variety of textual and symbolic annotations to clarify (and, in some cases, inadvertently confuse) formal features. In addition to the preface on fol. 70r, rubrics precede the first four songs indicating their identity as songs (“cantilenae”) for the Feast of the Nativity (see Figure 5.3). While rubrication of this type disappears after the first folio, the lyrical tags are added in such a way that they function as rubrics comparable to the French refrains in the St-Victor Miscellany. In Figure 5.4, for instance, two poems copied one after the other begin with a boxed lyric copied at the same time as the main text. The manner in which the scribe boxed off the fragmentary vernacular lyrics (in this case French and English) as a kind of title suggests an intention for the Latin poem to be read in relation to this header. Akin to the fully integrated French refrains of the St-Victor Miscellany, effort was made to incorporate the lyrical cues into the inscription of the songs in the Red Book of Ossory.

Figure 5.4 Red Book of Ossory, fol. 71v, Jhesu lux vera seculi and Jam Christo moriente.

Of the thirteen instances of song cueing, seven (including the two in Figure 5.4) are inscribed in this planned fashion.Footnote 68 The remaining six are not only less clearly a part of the original planning of the folios, but in many cases were later additions and/or the work of a different scribe. That several hands were involved in the copying of these folios is clear, with at least two text hands identified for the Latin poems alone (with a division in the first column on fol. 75r marking a distinctive turn in the types of texts being copied).Footnote 69At least one other hand annotated the collection, adding “amen” at the conclusion of many of the poems and also adding additional citations of vernacular – and one Latin – texts in the margins. The different hands can be seen in a comparison of the threefold appearance of the English line (or part thereof) “Haue mercie on me frere | Barfote þat y go” in Figure 5.5. Copied with a poem for Epiphany and two for Easter, this is one of only two English textual snippets with a concordance outside of the Red Book of Ossory (the other is the well-known Mayde yn the moore lay).Footnote 70

Figure 5.5 Red Book of Ossory, fols. 70v (a), 71v (b), and 73r (c) (details).

Only the lengthier version of “Haue mercie on me frere” on fol. 71v is fully incorporated into the mise en page in a way that suggests it was copied at the same time as the Latin poem that follows. By contrast, a different scribal hand boxed off the shorter forms of the lyric in the margins on fols. 70v and 73 r. On fol. 70v in particular, the hand responsible for the boxed lyric also seems to have added the concluding “amen.” In both of these shorter, marginal annotations, there are spelling changes too – “of” instead of “on,” and “mercy” (on fol. 70v) instead of “mercie” or “merci.”Footnote 71 Rather than added uniformly and at the same time as the Latin texts themselves, nearly half of the song cues appear to be a product of a process of adding to and editing the songs, undertaken by different hands at different times.

The recycling of this English lyrical fragment may witness the use and performance of the Latin poems by singers themselves, who, responding to the direction in the preface to provide suitable tunes (“notis”), added references to familiar songs as reminders of melodies that fit the formal contours and scansion of a given poem. This reinforces the impression of the song gathering as its own independent libellus, whose well-worn leaves indicate a degree of use that does not characterize the other gatherings of the Red Book of Ossory.Footnote 72 Perhaps similarities between songs (whether based on rhyme scene, meter, or form, etc.) caught the eye of a singer or scribe using the libellus, who then made note of this by adding new, marginal citations of musical models. Certainly, the Latin poems attached to “Haue mercie on me frere” all share the same general form – quatrains with a 7676 syllabic structure and ABAB rhyme scheme – making it plausible they could share the same melodic profile.Footnote 73

If some of the song cues resulted from an ongoing process initiated by use, this may explain mismatches between the poetic and formal features of the Latin texts and their vernacular models.Footnote 74 This certainly seems to be the case for the other vernacular lyric employed twice in the songbook, first planned and boxed off like a rubric on fol. 72r as “Do do nihtyngale synge ful myrie | Shal y neure for þyn loue Lengre karie,” and then in the upper margin on fol. 74r as “Do do nyȝtyngale Syng wel mury | Shal y neure for þyn loue Lengre kary.” The orthographic differences between the two citations are striking, and the Latin texts with which they are associated also do not match in syllable count or rhyme scheme: Dies ista gaudii on fol. 72r and Regem adoremus on fol. 74r.Footnote 75 Only Regem adoremus has a refrain indicated in the manuscript, while Dies ista gaudii, by contrast, has no refrain cued, although editor Edmund Colledge argues that the first quatrain (beginning “Dies ista gaudii”) probably served as a recurring refrain.Footnote 76 Colledge is guided in this by the English lyrical cue for the song of the nightingale, which he interprets as a refrain whose melody and implied formal structure shaped the performance of both Dies ista gaudii and Regem adoremus.

Despite the formal mismatch between the two Latin songs on the page, the addition of a shared English lyric may gesture toward a parallel form realized in performance – namely, a strophic form with a regularly recurring refrain. The English nightingale lyric and its remembered melody, in this case, are adapted to fit the two newly composed Latin songs while also, in turn, inflecting and informing their poetic structures. The process of annotation throughout the poetic collection emerges through examples such as this as one motivated by the needs and interpretations of singers and scribes, as well as a process that was inherently fluid in its application. Curiously, the fact that many of the song cues in the Red Book of Ossory were added over time seems to have been largely overlooked in favor of attributing authorship of the Latin texts and their lyrical cues to Ledrede. While Ledrede himself may have contributed to the creation and compilation of some of the Latin poems, he was almost definitely not responsible for all, if any, of the vernacular song cues. In other words, the collection probably represents a collaborative, rather than individual, effort.

As in the St-Victor Miscellany and the Engelberg Codex, citations to vernacular song in the Red Book of Ossory sketch a picture of the broader song culture within which the scribes, copyists, and singers were enmeshed. The presence of song cues in not only one vernacular but two, English and French, reflects the multilingual milieu of Ledrede’s clerical community in the Ossorian diocese of the fourteenth century.Footnote 77 Although the only English in the manuscript is attached to lyrics, the question of language, and English in particular, is not absent from the other contents of the Red Book of Ossory. In a 1360 Latin letter on fol. 55r from Edward III (r. 1327–1377) to the Sheriff of the Cross of Kilkenny and Seneschal of the Liberty of Kilkenny, English people living in Ireland who were speaking and raising their children in the Irish language were reprimanded and directed to learn English “on pain of loss of English liberty.”Footnote 78 French is not mentioned, although it was spoken and used in written communication and for transactions and official records in Ireland and England throughout the fourteenth century.Footnote 79 Ledrede was himself English, and as Colledge writes, his “stormy career has been represented as one chapter in the centuries-long chronicle of the struggle between the Irish and the English.”Footnote 80 The presence of Latin, French, and English in the poems of the Red Book of Ossory thus further marks the collection not as Irish, but rather as an effort closely linked to the influence of the English Bishop Ledrede and a longer history of language politics in Ireland.

The fragments of English song identify the Red Book of Ossory as a unique witness to a vernacular song practice with scant material remains – little survives of English-language song from this period. Notably, the transmission of rondelli with English song cues potentially supplements the otherwise lacking evidence for the English reception of the French rondeau.Footnote 81 In the Red Book of Ossory, three poems with song tags are rondelli: Jhesu lux vera seculi (fol. 71v); Plangentis Christi ulnera (fol. 72r–v); and Resurgenti cum gloria (fol. 72v). Of these, the first is accompanied by a French lyric, the second by a Latin incipit, and the third an English lyrical snippet, respectively. The French lyric has no concordances where one might expect to find them in the refrain tradition, although – as with the second of the two French cues in the Red Book of Ossory – it has all the poetic characteristics of a refrain. In this, the French cues in the Red Book of Ossory are close in spirit to the refrains in the St-Victor Miscellany, several of which likewise remain unidentified.Footnote 82 No concordances survive for the English lyric either, which is unsurprising considering its brevity and generic identity.

The marginal incipit of the Latin lyric, however, has a concordance within the Red Book of Ossory as the initial line of the refrain for another rondellus, En Christi fit memoria on fol. 70v (see Figure 5.6):Footnote 83

Figure 5.6 Red Book of Ossory, En Christi fit memoria, fol. 70v (a), and Plangentis Christi ulnera, fol. 72r–v (b) (details).

En Christi fit memoria Qua florent reflorent florida Da vera cordis gaudia. Cuius forti potencia En Christi fit memoria Cuncta flectentur genua Nutu fatentur subdita. En Christi fit memoria Qua florent reflorent florida Da vera cordis gaudia. | rubric: En Christi fit memoria Plangentis Christi ulnera Nittetur vox dulcisona Digna dans laudum cantica. Mutata sunt nam carmina Plangentis Christi ulnera De victa morte pristina Cum surgit die tercia. Plangentis Christi etc. |

Let there be remembrance of Christ, whereby all blossoms bloom and bloom again. Give us our hearts’ true joys. Before his great might, let there be remembrance of Christ, all knees will be bent, all things confess themselves subject to his will. Let there be remembrance of Christ, whereby all blossoms bloom and bloom again. Give us our hearts’ true joys. | rubric: Let there be remembrance of Christ The sweetly sounding voice shines forth of one who is mourning Christ’s wounds. For the songs are changed, of one who is mourning Christ’s wounds, when on the third day he rises from a previous death that he has conquered. Of one who is mourning Christ’s, etc. |

The Latin lyrical cue seems to be a later addition to Plangentis Christi ulnera based on its positioning and scribal hand, suggesting that a singer or scribe noted the formal and poetic parallels between the two rondelli. The melody for En Christi fit memoria, then, is reused for Plangentis Christi ulnera. Unfortunately, we have no indication of the original melody for En Christi fit memoria. What we do have is another rondellus, Resurgenti cum gloria, which survives with the English incipit “Haue god day my lemon &c” directly following Plangentis Christi ulnera on fol. 72v. Resurgenti cum gloria takes a near-identical form to both En Christi fit memoria and Plangentis Christi ulnera with respect to syllable count and rhyme scheme:

rubric: Haue god day my lemon &c Resurgenti cum gloria Gaudeat ecclesia Digne cantans alleluia. Rumpenti mortis vincula Resurgenti cum Gloria Pede calcanti tartara Vite reddenti premia Resurgenti cum Gloria etc. | In him who rises with glory, let the church rejoice appropriately singing Alleluia. In him who breaks the chains of death, in him who rises with glory, in him who treads down hell with his foot, in him who restores the rewards of life, in him who rises with glory etc. |

As Greene notes concerning the relationships between these three rondelli, the use of the first line of “En Christi fit memoria” as the cue for Plangentis Christi ulnera points to the similar refrain identity for the English marginal cue for Resurgenti cum gloria.Footnote 84 To put it another way, it is possible that “Haue god day my lemon &c” records the initial words of a longer rondeau refrain, mirroring the use of the refrain incipit of En Christi fit memoria at the head of another rondellus. For rondelli in the Red Book of Ossory, marginal cues are probably comprised of refrains, just as they are in the St-Victor Miscellany and the Engelberg Codex. Finally, if this is the case, then “Haue god day my lemon &c” may bear witness to a yet-unidentified English rondeau, just as the marginal annotations in the Engelberg Codex did to German rondeaux unknown until the discoveries of Kornrumpf. At any rate, it is clear that a scribe or singer recognized the underlying rondeau form of several poems and made an effort to visually and musically link poems capable of being realized using a single shared melody.Footnote 85

The fragmentary cues annotating Latin poems in the Red Book of Ossory bring to the fore once again the centrality of the refrain in the practice of contrafacture. This is the case even though, of the three manuscripts discussed in this chapter, the English, French, and Latin paratexts of this Irish compilation engage the least with refrain forms. Only six of the thirteen annotated Latin poems employ structural refrains; one other, Peperit virgo, features a highly repetitive (and frequently debated) form similar to several others in the Red Book of Ossory.Footnote 86 That nearly half of the Latin poems accompanied by lyrical paratexts feature refrains, however, is significant, as is the fact that refrains dominate the formal structures of the collection as a whole. Refrains are central to the lyrical and musical endeavors represented in the Red Book of Ossory, in addition to serving as the cornerstone in the textual inscription of contrafacture.

Despite the preface’s reference to melodies, no music survives for any of the Latin poetry in the Red Book of Ossory, nor for the vernacular cues and their concordances.Footnote 87 On the whole, it is a frustratingly unmusical collection, which goes a long way toward explaining its relative absence in musicological literature. Even in comparison with the similarly unnotated St-Victor Miscellany, the Red Book of Ossory offers far less in terms of sounding music, since certain of the French refrains transmitted in the Parisian collection survive with musical settings. Nevertheless, the Latin poetry of the Red Book of Ossory points to the ability of material manifestations of contrafacture to serve as a shorthand for music. Textual cues like those in all three manuscripts discussed here take the place of musical notation or, in the case of the Engelberg Codex, function as a placeholder before notation is added. While such a technique is employed in different ways across these three sources, the textual signaling of contrafacture virtually always denotes the existence of music in some form, even if its sonic contours are lost, audible only to those who once held the repertoire in their aural memories. For the poems of the Red Book of Ossory, this partly material, partly memorial practice affirms their identity as songs, even if the melodic component remains out of our reach and hearing. Moreover, the link between the preface and the following song cues frames contrafacture as inherently performative. Although inscription initiates the link, remembered melodies and new and old texts come together not on the page but through performance.Footnote 88

Refrains Across Language

This chapter has explored the interplay between Latin and vernacular song and refrain evidenced by cueing in and around the songs themselves in the form of rubrics and lyrical fragments. As the three manuscripts explored here uniquely showcase, refrains sit at the center of this practice of inscribing contrafacture. As the locus for linguistic and registral exchange and melodic sharing, refrains inscribed on the manuscript page encapsulate the underlying processes of contrafacture. This speaks to the weight of musical and poetic material embodied by the refrain – refrains can signal the overriding poetic structure (syllable count, rhyme scheme, etc.) for an entire song, just as the refrain’s melody can be employed across strophic material and refrain. Refrains, in other words, can serve as a stand-in for the entirety of a song as the “sticky,” memorable parts of song that readily embed themselves in the ear and memory.

While contrafacture often describes movement from secular to sacred, the examples discussed in this chapter neither affirm nor overtly contradict this registral directionality. Although the preface in the Red Book of Ossory advocates for replacing “secular” songs with “pious” substitutes, the intimate sharing of formal and musical structures manifested in the inscription of vernacular song across all three manuscripts argues against a strict dichotomy between the sacred and the secular. Song and refrain paratexts instead ensured the continued resonance of vernacular song regardless of register in the performance of Latin poetry. This is the case, indeed, for all contrafacts – the sharing of music by more than one text enables texts to be heard and interpreted against one another. Through the inscription of the vernacular texts on the page, moreover, the interaction of old and new, Latin and vernacular, silent and sounded, becomes more potent and direct.

The St-Victor Miscellany, Engelberg Codex, and Red Book of Ossory, in diverging yet parallel ways, testify to a link between Latin and vernacular song that orbits around the refrain. Across all three sources, moreover, rubrics and marginal lyrical fragments denote in some cases the sole surviving or earliest records of vernacular song and its refrains, whether the earliest French refrains in the St-Victor Miscellany or the refrains of German and English rondeaux. Above all, the trio of sources reflects the needs, song cultures, and conventions of circumscribed, local communities – an abbey school in Paris, a monastery in Engelberg, and a clerical community headed by an English bishop in the diocese of Ossory. Although most Latin refrain songs are not explicitly linked to vernacular song practices, these sources show how the refrain could be exploited as a site for the meaningful intersection of Latin and vernacular song. Scribes, copyists, and compilers provided material evidence for this relationship as it emerged from within localized and multilingual communities of song and singers, whether schools, monasteries, or regional dioceses. Despite the emphasis on inscription in all three manuscripts, the refrain emerges as a site of memory once again, namely the memory of melodies circulating across language within religious communities throughout Europe.