Introduction

In May 2023, Uganda reignited a politically charged debate on LGBTQFootnote 1 rights by signing one of the world’s most draconian anti-LGBTQ bills into law. The Anti-Homosexuality Act of 2023 mandates life imprisonment for anyone who engages in same-sex relations and calls for the death penalty for ‘aggravated homosexuality’. It criminalizes even advocacy: anyone promoting LGBTQ rights can face up to two decades in prison (Northam Reference Northam2023; Budoo-Scholtz Reference Budoo-Scholtz2023). Ugandan President Museveni defended the bill with a common rhetorical strategy linking LGBTQ rights to neocolonialism (Tamale Reference Tamale2011; Ngwena Reference Ngwena2018; Nyanzi Reference Nyanzi and Matebeni2014): ‘The homosexuals are deviations from normal. The Western countries should stop wasting the time of humanity by trying to impose their practices on other people’.

The Ugandan bill is one of several introduced across Africa in recent years – including in Kenya, Ghana, Tanzania, and South Sudan – despite considerable progress in countries like South Africa and Botswana. And rhetoric similar to Museveni’s has uniformly been weaponized by anti-LGBTQ elites who claim to be defending African culture against Western imposition (Lyon Reference Lyon2022, 700; Youde Reference Youde2017). In February 2024, Zimbabwe’s Vice President, Constantino Chiwenga, issued an official statement condemning a queer youth scholarship program as ‘unlawful, unChristian, and anti-Zimbabwean and unAfrican’, accusing ‘decadent’ foreign actors of attempting to ‘recruit Zimbabwe’s students into [LGBTQ] malpractices’ (ZimLive 2024). He closed by emphasizing that ‘Zimbabwe is a sovereign, African State’. These statements are part of a broader trend in which African states attempt to derive cultural and political authority by portraying LGBTQ rights as foreign impositions.Footnote 2 In doing so, they use ‘the West as an occidentalising rhetorical counter’ (Ngwena Reference Ngwena2018, 214) while pushing forward repressive legislation and fueling a human rights crisis for LGBTQ people in many states.

How can LGBTQ activists respond to such narratives in environments where universal human rights frames find less resonance? More specifically, do ‘rooted’ activist frames – those that link equality to local histories, values, and narratives – help shift public attitudes in such contexts? We offer the first experimental test of what we call ‘rooted’ frames in the African context. While human rights activism has long emphasized the universality of its claims – focusing on abstract human rights master frames – many activist groups have shifted their language to localized strategies in the past two decades (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020). We use the term ‘rooted’ to denote frames that draw on themes that resonate with a local population.Footnote 3 Such frames seek to counter the charge that human rights movements are ‘Western’ and ‘foreign’ (in this case, ‘un-African’) by focusing on their indigeneity and place within the broader national narrative (Chitando and Mateveke Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017).Footnote 4 This approach is evident – as we point out below – in contexts as diverse as Poland, Namibia, and Colombia. Yet despite their growing use, we know little about whether such strategies change public opinion, especially in high-stakes environments where backlash is a serious risk.

Our original research in Zimbabwe draws on focus groups and a 2023 survey experiment in two cities. The focus groups with local LGBTQ leaders surfaced a variety of rooted frames already in circulation – akin to ones that qualitative researchers have uncovered in many contexts discussed below – which we then tested in a controlled setting. We test two rooted frames: one that invokes indigeneity, presenting evidence of pre-colonial queer diversity, and another that emphasizes liberation, framing LGBTQ rights as part of Zimbabwe’s broader national narrative of anti-colonial struggle. Our findings show that these frames do no harm, and in some cases reduce homophobic attitudes. The indigeneity frame significantly reduces how upset respondents say they would feel if a neighbor came out as gay. The liberation frame, while producing more modest effects, increases support for equal rights. These results provide empirical support for activist strategies that rely on rooted messaging.

This study not only contributes to the literature on LGBTQ rights and social movement strategies in Africa; it also speaks to broader debates in political science about norm localization, backlash, and the conditions under which universal values gain traction. Our research tries to understand how activists can work most effectively in challenging contexts, addressing a longstanding call in social movements research to study the effect of framing on public opinion (Amenta and Polleta Reference Amenta and Polletta2019).Footnote 5 This paper makes three core contributions. First, it offers a rare experimental test of LGBTQ movement framing strategies in an African context, addressing the persistent empirical gap around whether and how such messaging can shift public attitudes. Second, it introduces and tests the concept of ‘rootedness’ in norm advocacy, showing that locally grounded framings – anchored in local histories or liberation struggle – can reduce anti-LGBTQ sentiment even in highly constrained environments. Third, the paper adds to ongoing debates about norm diffusion and backlash by identifying conditions under which universal rights claims may gain traction through contextually resonant framings. Together, these insights advance our understanding of social movements, norm contestation, and the possibilities for attitudinal change in electoral autocracies.

As the first systematic test of rooted frames – also in the wider human rights literature – it lends credibility to LGBTQ activist strategies that rely on such messaging. In an era of resurgent populism and cultural nationalism – where commonly used universal human rights frames are increasingly defunct and dismissed as elitist, foreign, or irrelevant (Baisley Reference Baisley2015) – our findings suggest that rooted, locally resonant frames may offer a viable path forward. This has implications for activism in a range of domains, from gender rights to anti-corruption campaigns, and in contexts well beyond Africa. The paper proceeds by situating LGBTQ rights contestation in comparative context and outlining the theory of rooted messaging, before discussing the experimental design and findings.

LGBTQ Rights Contestation and Social Movement Framing in Africa

In many states, LGBTQ movements are painted as ‘outsiders’ and their claims are dismissed as a ‘foreign imposition’. In Africa, opponents of LGBTQ rights have relied on the narrative that homosexuality is ‘un-African’ and represents an imperialist impulse of Western states to encroach on national sovereignty (Currier Reference Currier2012; Tamale Reference Tamale2011; Nyanzi Reference Nyanzi2013; Chitando and Mateveke Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017; Ngwena Reference Ngwena2018). In the previous three decades, leaders of several African countries – including Gambia, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe – have, to varying degrees, directly employed this ‘neocolonial/un-African’ frame, denouncing homosexuality as alien to African culture (Nyanzi Reference Nyanzi2013). Similar rhetoric has been echoed by religious leaders (Nyanzi Reference Nyanzi2013; 957; Dreier et al. Reference Dreier, Long and Winkler2020) and amplified in media discourse (Lyon Reference Lyon2022, 700; Winkler Reference Winkler2021; Baisley Reference Baisley2015).

This narrative has become so entrenched that ‘some LGB[TQ] advocates now argue that Western advocacy creates more harm than good’ (Lyon Reference Lyon2022, 700), by reinforcing perceptions that queer rights are externally imposed. The irony, of course, is that many African anti-sodomy laws were themselves colonial imports to challenge ‘unnatural offenses’, introduced by British administrators and left largely unchanged after independence (Han and O’Mahoney Reference Han and O’Mahoney2014; on Zimbabwe see Chitando and Mateveke Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017; Pinheiro Minillo Reference Pinheiro Minillo2022). As Jjuuko (Reference Jjuuko, Lennox and Waites2013, 406) notes, these laws remain one of the most enduring legacies of British colonialism.

They have not only persisted but expanded, often with backing from Western moral conservatives who have exported the American culture wars to more ‘winnable’ states and regions (Velasco Reference Velasco2023). Indeed, while anti-LGBTQ advocates frequently denounce LGBTQ movements as a ‘foreign imposition’, the anti-LGBTQ moral conservative movement is itself globally linked (Corrêa et al. Reference Corrêa, Paternotte and Kuhar2018). In Africa, for example, Evangelicals from the United States have campaigned against the LGBTQ community and their claims to equal rights (Bob Reference Bob2012; Velasco Reference Velasco2023). Groups like the International Organization for the Family (IOF) focus centrally on targeting LGBTQ people, channeling funds, commissioning lawyers, and drafting bills to share with sympathetic audiences (Ayoub and Stoeckl Reference Ayoub and Stoeckl2024). In Uganda, for instance, US religious figures helped inspire the infamous 2009 Anti-Homosexuality Bill, a predecessor of the 2023 Act (Nuñez-Mietz and Garcia Iommi Reference Nuñez-Mietz and García Iommi2017). These actors, along with domestic religious and political leaders, have framed homosexuality as immoral, unnatural, and un-African, often for strategic political gain (Currier Reference Currier2012; Dreier Reference Dreier2018; Rao Reference Rao2020) – suggesting that state-sponsored homophobia, rather than homosexuality itself, may be at least partly the result of undue Western influence in Africa.

These dynamics are not unique to the African continent, however, as LGBTQ-opponents deploy the ‘neocolonial’ frame in many places. In Russia, LGBTQ movements are classified as ‘foreign agents’ (more recently, ‘extremists’) of the West, and in many Eastern European states their work is characterized as an imposition of the European Union, even an ‘Ebola from Brussels’ (Korolczuk and Graff Reference Korolczuk and Graff2018). Research, for example in Georgia (Mestvirishvili et al. Reference Mestvirishvili, Zurabishvili, Iakobidze and Mestvirishvili2017), shows that publics do internalize the ‘foreignness’ messages unless local movements can successfully dislodge that association. Thus, LGBTQ movements in countries from Poland to Ghana have re-framed their issues to highlight their indigeneity, deflecting accusations that they are part of an international agenda to impose external values. This work of ‘rooting’ the movement has re-shifted movement frames downward – to the local dimension – in many states (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020).

In Africa, movements have worked tirelessly to expose the colonial origins of anti-LGBTQ sentiment and dislodge the ‘un-African’ frame by foregrounding pre-colonial histories of same-sex intimacy (Currier Reference Currier2012; Jjuuko Reference Jjuuko, Lennox and Waites2013; Nyanzi Reference Nyanzi2013). While much of the recent literature has documented the backlash and politicization of LGBTQ rights across Africa, there are also notable exceptions where important (and for us informative) progress has occurred – often through strategic, non-confrontational, locally resonant framing. South Africa remains a globally pioneering case, where LGBTQ activists embedded their claims in the anti-apartheid struggle and secured constitutional protections by emphasizing shared belonging (Devereaux Evans Reference Devereaux Evans2023). In other countries – such as Rwanda and Mozambique – activists have pursued quieter, elite-focused strategies or emphasized respectability politics, often adapting to restrictive political environments (Paszat Reference Paszat2022; Gomes da Costa Santos and Waites Reference Gomes da Costa Santos and Waites2022). Though rooted frames are not always central, these examples show that aligning LGBTQ claims with national narratives – whether public or discreet – can help carve space for rights advancements. Evidence from other, non-LGBTQ, domains suggests this strategy may have broader relevance. In Nigeria, anti-corruption messages grounded in local or subnational-level references were more persuasive than further-detached ones (Cheeseman and Peiffer Reference Cheeseman and Peiffer2023), while in Uganda, appeals invoking traditional authorities – and thus, rooted ways of life – proved most effective (Goist and Kern Reference Goist and Kern2018). These findings underscore the power of contextually grounded messaging in environments where universalist appeals often lose traction.

Our study contributes to this growing body of work by testing the persuasive power of rooted frames in a domain – LGBTQ rights – that is especially susceptible to ‘foreignness’ backlash. Despite the openings this recent work offers, we still know little about whether rooted human rights frames can change public opinion towards marginalized communities. This matters because increased public support is key to advancing legal protections and reducing the everyday harassment and violence faced by LGBTQ people (Lyon Reference Lyon2022, 698). Public opinion data on LGBTQ rights remain limited in the region (Dreier Reference Dreier2018; Dionne and Dulani Reference Dionne and Dulani2013; Winkler Reference Winkler2021), and few studies have examined how specific messages shape attitudes. We thus theorize and test two types of rooted frames: one that emphasizes indigeneity by placing LGBTQ rights within African culture, and another that connects LGBTQ rights to national liberation narratives. Examining potential drivers of public opinion shift, Lyon (Reference Lyon2022) experimentally tested whether information about other African countries or Western countries that had implemented LGBTQ protections could influence acceptance in Uganda. He found that one-off messages from neither African nor Western sources shifted public opinion, suggesting that perhaps foreign messages of any origin may generate backlash from local actors who view such messages as an intrusion on their national sovereignty (716). We build on this finding by testing domestic messages that root LGBTQ claims in Zimbabwe’s own history and narratives. In doing so, we examine not only whether these frames shift attitudes, but also whether they can avoid backlash in a highly constrained environment.

Theory: Rooting LGBTQ Rights

Homosexuality in Zimbabwe has been condemned, in part, because the discourses that have been used to narrate homosexuality have not necessarily been ‘Zimbabwean’

(Chitando and Mateveke Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017).

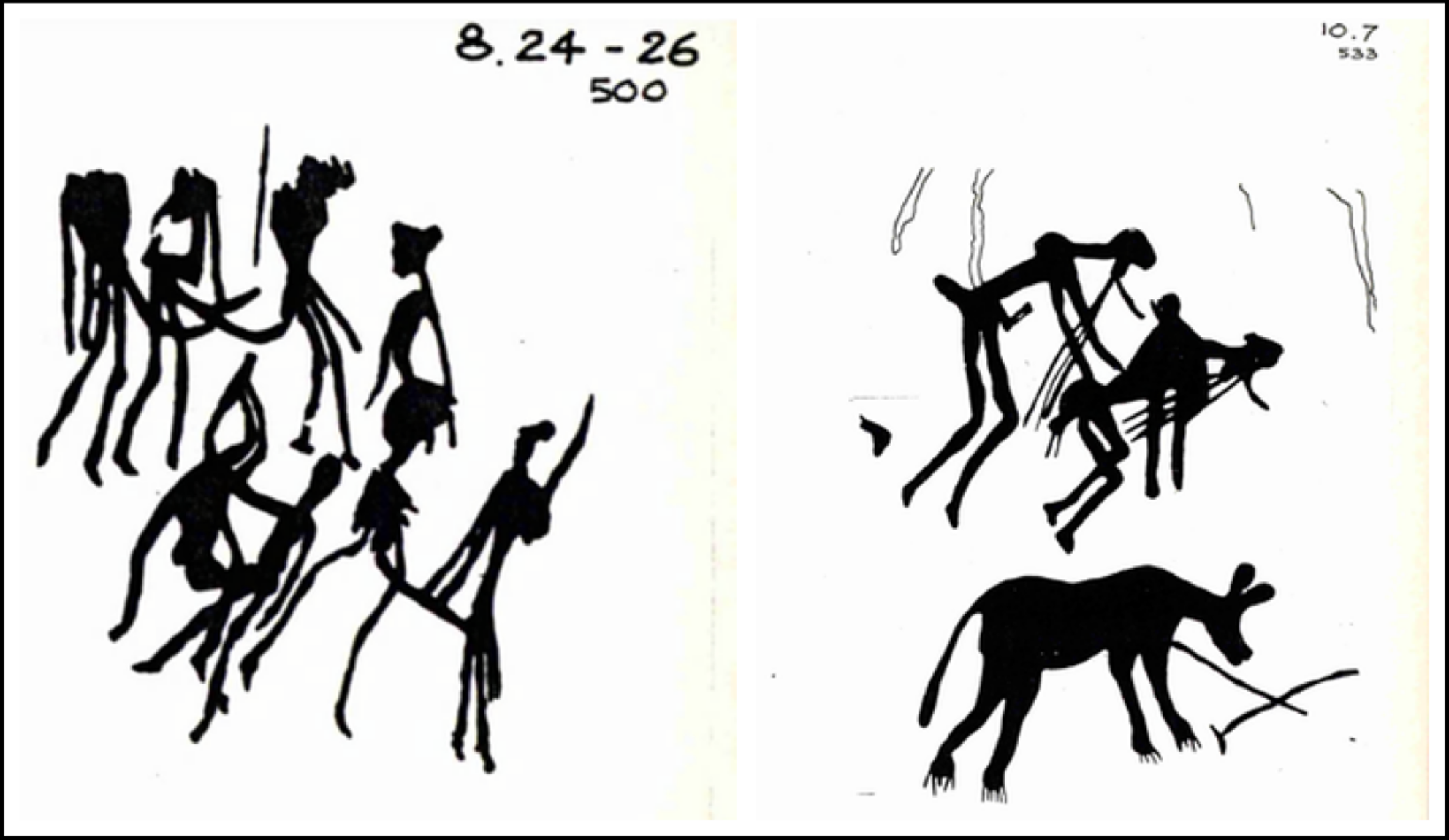

We test the effectiveness of these ‘course correcting’ or ‘rooting’ messages on attitudes towards homosexuality and a willingness to support equal rights for the LGBTQ community. By ‘rooting’, we refer to the intentional framing of LGBTQ people within local histories and contexts that resonate with local communities (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020). The mechanism by which this works is the direct challenge that messages like this deliver to the ‘neocolonial’ frame; they dismantle the foreign imagery that opponents attach to LGBTQ people and their associated rights (Merry and Levitt Reference Merry, Levitt, Hopgood, Snyder and Vinjamuri2017). For example, Epprecht (Reference Epprecht2004) and Macharia (Reference Macharia2009) have charted pre-colonial articulations of same-sex desire in Africa. One of Zimbabwe’s greatest tourist attractions, the Great Zimbabwe, holds ancient paintings of San people engaged in affectionate expressions of same-sex love. In addition, caves in Guruve, Zimbabwe, also hold paintings that archaeologists say depict such love (Garlake Reference Garlake1992), examples of which are shown in Figure 1.Footnote 6 We expect that by directly countering the ‘foreign/colonial’ frame, this rooting mechanism might make the issue less threatening and more meaningful to the public. In doing so, it dovetails with the concept of norm brokerage in the international relations literature, in that local actors can root contentious international norms by repackaging them for local audiences (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). Focus groups with Zimbabwean LGBTQ activists illuminated the various frames that organizations are trying to deploy, most of which attempt to dislodge LGBTQ rights from neocolonial counter-arguments.

Figure 1. Pre-colonial cave paintings (reproduced as sketches) near Guruve in Zimbabwe.

Source: Garlake (Reference Garlake1992, 450–616); see also Mehra et al. (Reference Mehra, Lemieux and Stophel2019).

Under the wider umbrella of Africanizing LGBTQ rights by rooting them locally, activists in our focus groups suggested two key strategies.Footnote 7 One strategy roots the message by shining a light on queer history and its pre-colonial, indigenous origins, such as making people aware of the cave paintings in Figure 1. Drawing on the work of Zimbabwean scholars and activists, we call this type of rooted frame the ‘indigeneity frame’. By highlighting the rightful place of queer people alongside wider Zimbabwean society, it may serve in particular to reduce homophobic attitudes towards individual LGBTQ Zimbabweans. It does so by offering ordinary people legitimate ways of relating to each other and their bodies through a specific type of knowledge focused on their group. It is also about writing an unfinished history (‘colonialism disrupted African history’) by motivating the folding in of others in the local society. For example, Chitando and Mateveke’s (Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017) passage captures the spirit of our focus group participants:

The rhetorical power of the concept ‘indigenous’ is enormous, especially in Southern Africa where it seeks to affect a distinction between ‘sons and daughters of the soil’ and ‘foreigners/outsiders’… To describe homosexuality as indigenous is to preempt the charge that it is a product of Western cultural imperialism (132–3).

A second rooting strategy draws directly on overarching national narratives. This is a different type of rooting message, linking to locally resonant patriotic histories (Youde Reference Youde2017; Tendi Reference Tendi2010), which in Zimbabwe focuses on the full liberation of all Zimbabwean citizens from minority rule. While these histories are also intrinsically connected to protecting the nation from outside influence (such as real and perceived neocolonialism), activists and scholars of Zimbabwe note the importance of contributions to and aspirations towards the country’s liberation, which hold tremendous legitimacy locally (Youde Reference Youde2017; 65; Tendi Reference Tendi2010). The liberation narrative in Zimbabwe, dominated by ZANU-PF’s emphasis on military efforts, has often marginalized other forms of resistance and community struggles, particularly those of queer communities who now try to reclaim it (Muchemwa Reference Muchemwa2023). For example, according to our interviews, GALZ (An Association of LGBTI People in Zimbabwe, formerly Gays and Lesbians of Zimbabwe) uses the legacy of Zimbabwe’s liberation struggle to position queer individuals within the narrative of national belonging and liberation (see also Pinheiro Minillo Reference Pinheiro Minillo2022, 141).

What we call the ‘liberation frame’ starts from the resonant observation that even though African nations have liberated themselves from colonial and white minority rule, not all people in these societies (or in most societies) enjoy full equal rights under the law. We therefore expect that presenting liberation as incompleteFootnote 8 and in need of continued effort, including in regard to LGBTQ communities, will increase sympathy among citizens. Indeed, Zimbabweans place great value on liberation as an important part of the national struggle and narrative. Since the liberation frame is also directly linked to rights, it is grounded in a political motivation and may be a pathway for increasing attitudinal support for rights protecting LGBTQ people.

In sum, rooting may deconstruct knowledge about sexuality in a way that introduces new ways of thinking about proximate communities within one’s society. Indeed, African queer scholarship anticipates the transformative power in rooting: ‘Africanizing the discourse on homosexuality offers the perfect opportunity for Africans to have indigenous concepts that help them to recognize themselves as well as others’ (Chitando and Mateveke Reference Chitando and Mateveke2017, 137). We test this, theorizing that linking the LGBTQ cause to the larger cause of African independence and rights should increase sympathy for this discriminated group. We pre-specified the following hypotheses:

HYPOTHESIS 1: An indigeneity message that roots homosexuality in African history and de-links it from Western influences/origins will lower homophobic attitudes.

HYPOTHESIS 2: A liberation message that links anti-homosexual laws and attitudes to locally rooted, resonant narratives of limited liberation/freedoms/rights will increase support for LGBTQ equal rights. Footnote 9

Despite widespread and strongly held anti-LGBTQ attitudes in Zimbabwe and much of Africa, we expect that attitudes can be moved to be more accepting of LGBTQ people and/or increase willingness to support their rights. Indeed, the persuasion literature, both generally and concerning LGBTQ attitudes specifically, suggests that strongly held attitudes are malleable (Winkler Reference Winkler2021; Ayoub et al. Reference Ayoub, Mironova and Whitt2025). For example, Coppock’s (Reference Coppock2022) work convincingly challenges motivated reasoning arguments by showing that positions on gun control, abortion, and LGBTQ rights in the United States are changeable. Further, recent research has found that more in-person and in-depth discussions, as well as more personally relevant discourse, can persuade people to be more supportive and accepting of the LGBTQ community (Kalla and Brookman Reference Kalla and Broockman2020). Thus, we expect that our indigeneity and liberation messages, which are rooted in Zimbabwean identity and history, will resonate on a personal level with respondents and as such impact reported attitudes.

The Zimbabwean Case

Like many post-independence African states, Zimbabwe has been governed by an authoritarian regime dominated by a single party. While many states on the continent transitioned to democracy in the 1990s, Zimbabwe, like Tanzania, Uganda, Mozambique, and others, has continued to be dominated by a single ruling party that is largely unaccountable to the mass public. Though elections are held, they have faced violence and/or irregularities and the ruling ZANU-PF has remained in power despite losing contests (for example in 2008). And as in many electoral autocracies, such regimes enjoy structural advantages like access to state resources and the ability to manipulate electoral processes (Bleck and van de Walle Reference Bleck and van de Walle2018). Zimbabwe also mirrors much of the continent in exhibiting high levels of homophobia.

The LGBTQ community has been used as a scapegoat or to score political points with the masses in Zimbabwe in the past. While it has not seen comparable levels of elite-led mobilization or legislative debate in recent years, Zimbabwe was an early adopter of the ‘un-African’ frame (Muchemwa Reference Muchemwa2023; Pinheiro Minillo Reference Pinheiro Minillo2022; Youde Reference Youde2017). In 1997, President Robert Mugabe declared, ‘Let the Americans keep their sodomy… Let them be gays in the US and Europe. But in Zimbabwe, gays shall remain a very sad people forever’ (Reddy Reference Reddy2002, 164).Footnote 10 While state-sponsored homophobia has been somewhat on the decline since Mugabe was forced out of office – the decline perhaps in part because many people recognized his using the issue to distract from the real social problems (Frossard de Saugy Reference Frossard de Saugy2022) – societal homophobia persists. President Mnangagwa and the ZANU-PF leadership show some willingness to engage with LGBTQ activists, but neither they nor the main opposition leader at the time of this study (Nelson Chamisa) were willing to advocate for rights (Muchadya Reference Muchadya2018). For example, discussions over an outed teacher in 1999 exposed widespread anti-homosexual sentiment online that even united people across the polarized political divide (Evans and Mawere Reference Evans and Mawere2021).

On attitudes, Zimbabwe ranks average to above-average in homophobia relative to other African countries, making it an informative and ‘hard’ case for testing framing effects. Drawing on major cross-national datasets (World Values, PEW, Afrobarometer), Dionne and Dulani (Reference Dionne and Dulani2013) report that most African countries fall between 68–78 per cent in levels of homophobia, with Zimbabwe’s rates ranging from 74 per cent (2012) to 96 per cent (2001) over time.Footnote 11 To assess the case’s generalizability, we replicated Dionne and Dulani’s models using both our dataset and Zimbabwe’s Round 7 Afrobarometer urban subsample. As shown in Appendix 7, the predictors of homophobia align closely across both samples and with broader regional patterns – indicating Zimbabwe is not an outlier, the drivers of homophobia are consistent with prior research, and, given Zimbabwe’s high levels of homophobia, it represents a difficult case, making any observed attitude shifts especially noteworthy.

In terms of legal status, Zimbabwe also sits in the middle of the Southern African spectrum. While it has not proposed laws as punitive as those in Malawi or Uganda, it has also not made the legal strides seen in Botswana, Mozambique, or South Africa. These countries revised colonial-era penal codes or implemented inclusive legislation, with South Africa leading in 2006 with marriage equality. Zimbabwean activists, particularly GALZ, had lobbied for protections during the 2013 constitutional reform process, but were unsuccessful (Youde Reference Youde2017). Zambia, like Zimbabwe, remains stagnant, while Malawi has more greatly politicized its opposition to LGBTQ rights.

While Zimbabwe has a committed and mobilized LGBTQ movement, its work of shifting attitudes in this context – among the lowest rates of LGBTQ visibility and acceptance in the world – is undeniably challenging (World Values Survey 2020). We thus also do not necessarily expect those who are treated in our sample to become allies or be supportive of LGBTQ causes and communities. Activists say they would be glad to confirm that the primes would not elicit backlash, potentially offering a test of how to ‘open the door’ to more meaningful and in-depth conversations. We nonetheless optimistically theorized that overall levels of homophobia would decrease to some degree in our pre-analysis plan, but acknowledge the difficult context of political homophobia (see Currier Reference Currier2019) at hand. In sum, Zimbabwe offers an informative case for this study. Attitudes on homophobia are comparable to many states on the continent and incredibly restrictive. Further, anti-LGBTQ legislation was not actively under debate during the study, allowing us to test framing effects outside of a highly polarized legislative moment in a way that might enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Data and Methods

Focus Groups

The first step in our research design involved conducting two focus groups with members of Zimbabwean LGBTQ advocacy organizations (one in Harare and another in Bulawayo). Rather than designing our experimental primes in isolation, we collaborated with activists to develop messages that reflected frames already circulating in their strategic repertoires. This ensured that the interventions we later tested were not only empirically grounded but carried grassroots legitimacy and local resonance. As della Porta (Reference Della Porta and della Porta2014, 291) observes, focus groups are particularly effective ‘for analyzing cultural themes, especially among those groups that are normally without a voice’, and allow researchers ‘to observe the collective framing of an issue’. Our aim was similarly to capture and co-produce the local discursive field, rather than impose an external framework onto it. The resulting frames were thus the product of a deliberative process with practitioners embedded in the everyday work of advocacy.

As described in greater detail below, four key narratives emerged from our discussions with these groups and advocates. The two types of frames that came up the most fit directly with the rooted narratives we have addressed above: an indigeneity frame, which focuses on the African origins of homosexuality; and a liberation frame, which highlights that the LGBTQ community is not fully liberated because they do not enjoy equal rights. In wider discussions, other narratives addressed also aimed to dislodge stereotypes in society. These included an ‘economy’ frame (see the Malawian ‘prosperity’ or ‘gay for pay’ frame in Currier Reference Currier2019); and a ‘just like you’ frame. Some scholarship has also identified the use of religious frames in LGBTQ activism, though this frame featured less centrally during our focus groups (cf. Appendices 3 and 10 for a further discussion). We test only the narratives that are most prominently used in Zimbabwe. There are trade-offs in this decision, given that we do not include non-rooted frames or a universal human rights frame for direct comparison; however, because the rooted narratives were the ones most emphasized by activists in our focus groups – and because such frames remain underexplored in quantitative research that has focused on universal frames, alongside our own limited resources and desire not to feed into a ‘foreignness’ trope – we prioritized testing these locally resonant strategies.

Beyond shaping the content of our experimental treatments, the focus groups and later discussions with enumerators served as a critical check on the contextual sensitivity and ethical viability of our proposed messages. Participants helped us reflect on tone, terminology, and potential risks associated with various framings. One advocate explained, ‘It is hard for our community to speak directly [to people], so we [also] let allies speak… It is easier for people to understand from people with more in common with them’. These conversations helped clarify not only what kinds of messages might resonate but also how they might be received by different publics. Our use of focus groups aligns with traditions in movement studies that treat them as sites of meaning-making and strategic reflection (Melucci Reference Melucci1989; della Porta Reference Della Porta and della Porta2014). In this sense, the focus groups were not simply background consultations but integral to the co-construction of our experimental design. This attention to local interpretive processes helps bridge to the next section, where we describe the survey experimental design in detail. Full procedural details, including ethical review, verbal consent, and compensation, are provided in Appendices 2 and 3; additional frames are in Appendix 10.

Survey and Experimental Design

We investigated the effectiveness of rooted messages via a survey experiment with citizens in Harare and Bulawayo. The survey was translated into Shona and Ndebele and was implemented in late May 2023. The sample included 1,198 respondents: 689 in Harare and 509 in Bulawayo.Footnote 12 As a robustness check, we conducted a second survey to validate our findings one year later in 2024, with an additional sample of 600 respondents in Harare (which we discuss in Appendix 9; the sampling approach follows the approach of the main survey but also includes medium and low density areas). We surveyed urban areas and used a random sampling procedure to ensure our survey sample was representative of high-density areas.Footnote 13 We stratified our sample on the 2018 vote share to ensure variation in partisanship in the sample. See the Appendix for more details on sampling and refusal rates. It is worth noting that our initial survey was conducted in the context of the 2023 Harmonized Elections (president, parliament, and local). Respondents engaged with our rooting messages when campaigning in earnest had not yet begun. Even though LGBTQ issues have come up in campaigns in the past, LGBTQ issues did not feature in meaningful ways in the 2023 elections. In fact, a focus group respondent indicated that ‘this is only the second election where we have felt safe, but we still wonder, “will they scapegoat us this time?”’

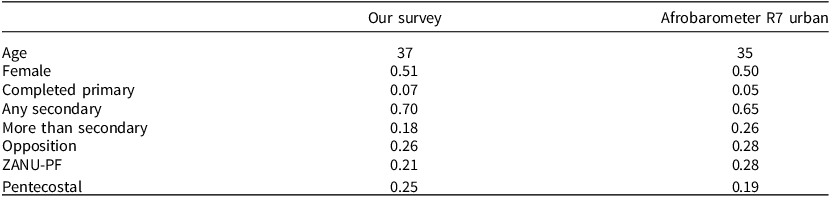

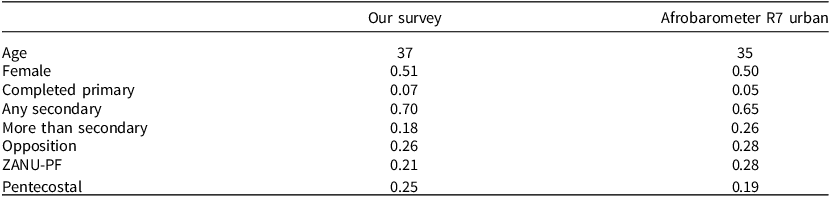

While our sample focused on high-density areas, these areas account for most urban residents across Zimbabwe. In Table 1, we present comparisons on key variables between our sample and the urban sample of the Zimbabwe R7 (2018) survey. Table 1 indicates that in terms of average age, gender distribution, education, and partisanship, our sample is on par with the Afrobarometer sample. Given that our sample is not younger, more educated, more female, or less supportive of the ruling party, there is little worry that our sample would be easier to sway with our treatment. Further, our sample is relatively more, not less, Pentecostal, which might suggest that our sample could be harder to move, given strong attitudes against homosexuality among Pentecostal congregations across the continent (Dreier et al. Reference Dreier, Long and Winkler2020).

Table 1. Representativeness of the sample

A survey-experimental approach is especially helpful for answeringFootnote 14 our research question because it allows us to compare the effectiveness of different messaging that LGBTQ activists use to combat anti-LGBTQ attitudes. Importantly, by designing it in conjunction with advocates in focus groups, we also benefit from grounding the research in ways that may have real-world relevance and impact. In the experiment, respondents were randomly assigned to receive one of two treatment messages or a control message. This allows us to estimate the causal effect of each message on LGBTQ attitudes by comparing attitudes between the control group and each group that received a treatment message. This in turn helps us to test theoretically driven ways to shift public opinion that might be useful to activists. After respondents saw one of the messages, we then asked questions to ascertain their attitudes towards the LGBTQ community.

It is important to note that we use the term ‘homosexual(ity)’ as a stand-in for the LGBTQ community in the survey itself. In Shona, homosexuality is ‘hungochani’, and in Ndebele, it is ‘ubutabane’. Both are indigenous terms rather than English imports or cognates and are used in everyday language. Many respondents, as our survey partners made clear, would not understand the LGBTQ acronym or the subgroups it represents. Table 2 presents the treatment and control texts used in the experiment.

Table 2. Experimental treatment and control conditions

All three primes communicate accurate information, but the pre-colonial history of queer Africans is largely unknown to the average citizen. However, a focus group respondent indicated that some ‘chiefs know this history of our queer ancestors’, inspiring some activists to think through how to use this knowledge in their campaigns. The goal of the indigeneity prime is to illustrate the history of queer Africans to show how they were part of and incorporated (to varying degrees) into society before colonization. Further, the prime signals that anti-gay laws and practices have colonial origins and themselves could be considered un-African.

The liberation prime presents Zimbabwean liberation as incomplete due to violations of equal rights. This seeks to prompt respondents to see the violation of LGBTQ rights as part of the larger injustices faced by society. Therefore, the indigenous treatment seeks to provide a corrective to the narrative that homosexuality is foreign while the liberation treatment seeks to evoke sympathy for a demonized group by presenting them as equally deserving of liberation and equal rights. Both are rooted in Zimbabwean history, which necessarily features colonization (Youde Reference Youde2017). Upon designing these frames, we expected that these treatments would provide people with new ways to think about their history and the place of LGBTQ people in society.

The colonial origins of anti-LGBTQ laws are shared across much of the continent, but the specific ways that queer histories are invoked will necessarily vary – a core feature of our ‘rooting’ concept, which by definition emphasizes contextual specificity. We thus do not expect identical histories (like cave paintings) or narratives (such as liberation) to appear everywhere, nor is this required. In nineteenth-century Germany, activists linked homosexuality to national icons like Frederick the Great (Beachy Reference Beachy2014). In Angola, male diviners practiced the embodiment of female spirits; among the Langi and Baganda in Uganda, men married men, with King Mwanga II openly gay; in Cameroon, same-sex marriage was used to transmit wealth; and in Sudan, warrior marriages to men were documented. These and other localized histories could be deployed to construct rooted indigeneity frames. Of course, in some contexts, our strategy of visual heritage – like ancient queer Egyptian or Thai art – may also be directly engaged to historicize queerness.

Finally, the control prime invokes history but does not explicitly mention the LGBTQ community. Importantly, this control prime explicitly mentions pre-colonial Zimbabwe, colonial disruption, and liberation. This allows us to test the effects of colonial and liberation history alone and thus tease out the effect of linking these histories to the LGBTQ community’s plight today. Colonial history is necessarily present in all three narratives given the context we work in. The approach likely underestimates the effects of linking LGBTQ lives with colonial and liberation histories because the control group also includes information about colonial/liberation histories, which suggests our experiment estimates lower bounds of such messages on attitudinal change.

Each prime is preceded by a short preamble in the survey to signal a change in topic and, for the two treatments, to prepare respondents (and enumerators) to discuss homosexuality: this is important because homosexuality is a highly sensitive topic and it was necessary to minimize discomfort for both the enumerators and respondents. We worked at length with enumerators and experts to get this right (see Appendix 3). Following the prime, we then asked respondents four outcome questions (ordering was not randomized). We first asked how important the respondent felt understanding history is to making sense of current affairs (four-point response scale: ‘very’ to ‘not at all’ important). This was a warm-up question, but importantly, for the control group, it ensures that they have a question that directly links to the historical narrative (as it may otherwise seem odd to present a historical narrative and then jump right to questions about homosexuality). This is not a core outcome, but we do present results for it in Appendix 6.

We then asked each respondent, ‘Which of the following best describes your perspective: (1) Homosexuality is un-African, (2) Homosexuality is part of African society even if I disagree with it personally, or (3) Homosexuality is part of African society, and I agree it has a place in our society’. As we pre-specified, we coded this variable in two ways. First, given the high rates of homophobia in this context, we code those who respond with statement 1 as 0, and those who respond with statement 2 or 3 as 1 to predict relatively positive views of homosexuality. Second, to detect degrees of views regarding how un-African homosexuality is, we coded an ordinal variable as 0 (un-African), 1 (African even if I disagree with it personally), and 2 (African), which is increasing in positive attitudes. Given our (pre-specified) expectation that very few people will agree that homosexuality is African without reservation, our primary coding is the first coding.

To tap into a more proximate and social dimension, we also asked, ‘What would be your reaction to one of your neighbors coming out as homosexual?’ For this neighbor question, we coded those who say very or somewhat upset as 0 and all others (indifferent, supportive, and accommodating, regardless of strength) as 1; this coding was pre-specified.Footnote 15 Finally, we asked if respondents agreed with this statement: ‘Homosexual people deserve human rights laws that protect them, just like everyone else’ (five-point response scale: strongly disagree to strongly agree). We code disagreement responses as 0 and code ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘don’t know’, and ‘agreement’ (regardless of strength) as 1. Once again, most people in our context hold strongly homophobic attitudes, so even moving people to the position of not knowing where they stand on the issue is an improvement (per local experts). We report the distribution of responses to each of our outcome variables in the Appendix.

This design presents several innovations in the study of LGBTQ politics in Africa. First, it is the earliest study of which we are aware to systematically test the effects of rooted messages on attitudes. Second, few studies on the African context experimentally test messages meant to reduce homophobia. Lyon (Reference Lyon2022) took important initial steps in this space by experimentally testing the effectiveness of messages to reduce anti-LGBTQ attitudes in Uganda. His study does not test social movement theorizing around rooted messages nor the role of local actors and history in influencing attitudes. Given his largely null findings regarding foreign-origin messages, we expect more rooted and domestically contextualized messages to have an impact (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020), in that they are necessary to make internationally circulating norms resonant via norm brokerage (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016). Third, by co-designing these messages with the activists doing this work on the ground, we try to come as close as possible to approximating the real-world context of LGBTQ politics in Zimbabwe.

It is important to note that, here too, there is a possible backlash effect (O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2018). Some respondents may object to the portrayal of homosexuality as indigenous to Africa altogether. However, we have taken measures in our treatments, in partnership with Zimbabwean enumerators and activists, to consider how to introduce the topic. First, we ease people into a discussion of homosexuality, using the above-mentioned preamble. Importantly, we do not directly say that homosexuality is African but rather indicate that the cave paintings suggest it is not un-African. Therefore, we reference historical research and actual activist frames to suggest documented alternative narratives to popular memory, without too forcefully pushing a commonly erased history. We also make sure to link the colonial origins of anti-homophobic laws and attitudes with other well-known negative colonial influences such as land theft and racism. Importantly, if there is any backlash effect, we would benefit from knowing this, as activists in Zimbabwe are deploying such appeals in their ongoing campaigns.

As pre-specified, we will estimate difference of means tests between each treatment and the control for each outcome variable to evaluate H1 and H2 (Lundberg et al. Reference Lundberg, Johnson and Stewart2021). As noted above, the outcome variables are coded to indicate less negative/more positive views towards the LGBTQ community.

Results

We first investigate the effects of our survey experiment and then explore the predictors of homophobia in Zimbabwe and compare them briefly to continental trends.

Survey Experiment Results

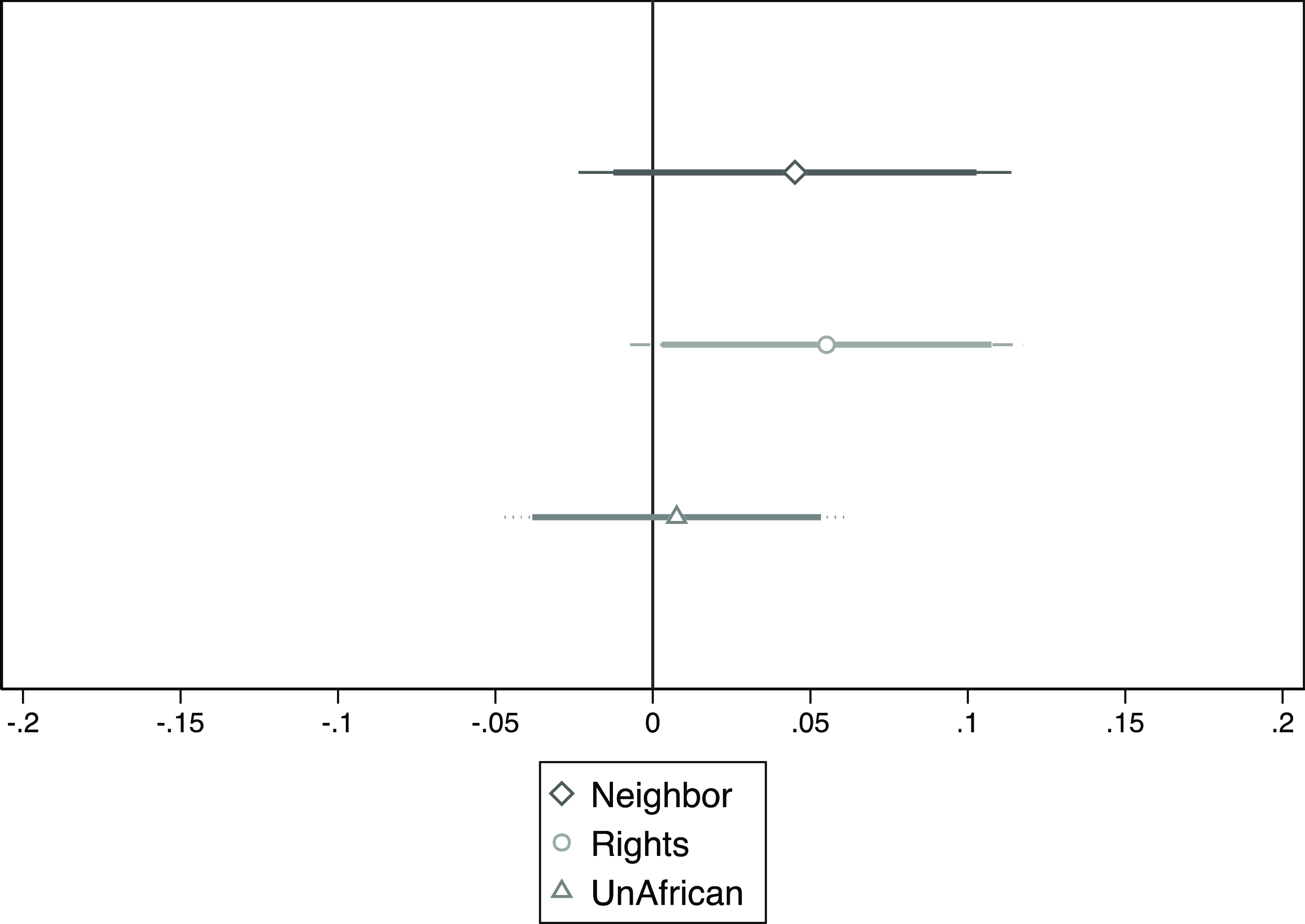

Figures 2 and 3 report the results from the difference of means tests. Figure 2 presents the treatment effects of the indigeneity prime relative to the control prime. In every instance, the treatment group average is higher than the control, which suggests no evidence of backlash, despite two out of three outcomes failing to reach significance. We do find an effect of the indigeneity prime on attitudes towards a neighbor coming out (indifference, don’t know, and supportive are coded as 1), which confirms H1. Those who received the indigeneity prime are 8 percentage points more likely not to be upset by a neighbor coming out.Footnote 16 This is a meaningfulFootnote 17 and surprising shift given the context. Indeed, this finding also makes the most sense for the indigeneity prime, given it invokes a history of queer Zimbabweans sharing spaces, side-by-side with others within society.

Figure 2. Difference of means tests for indigeneity rooting treatment.

Note: This figure plots the difference between the indigeneity prime and the control group along with the 90 per cent and 95 per cent confidence intervals. Positive differences indicate the treatment moved people away from homophobic attitudes.

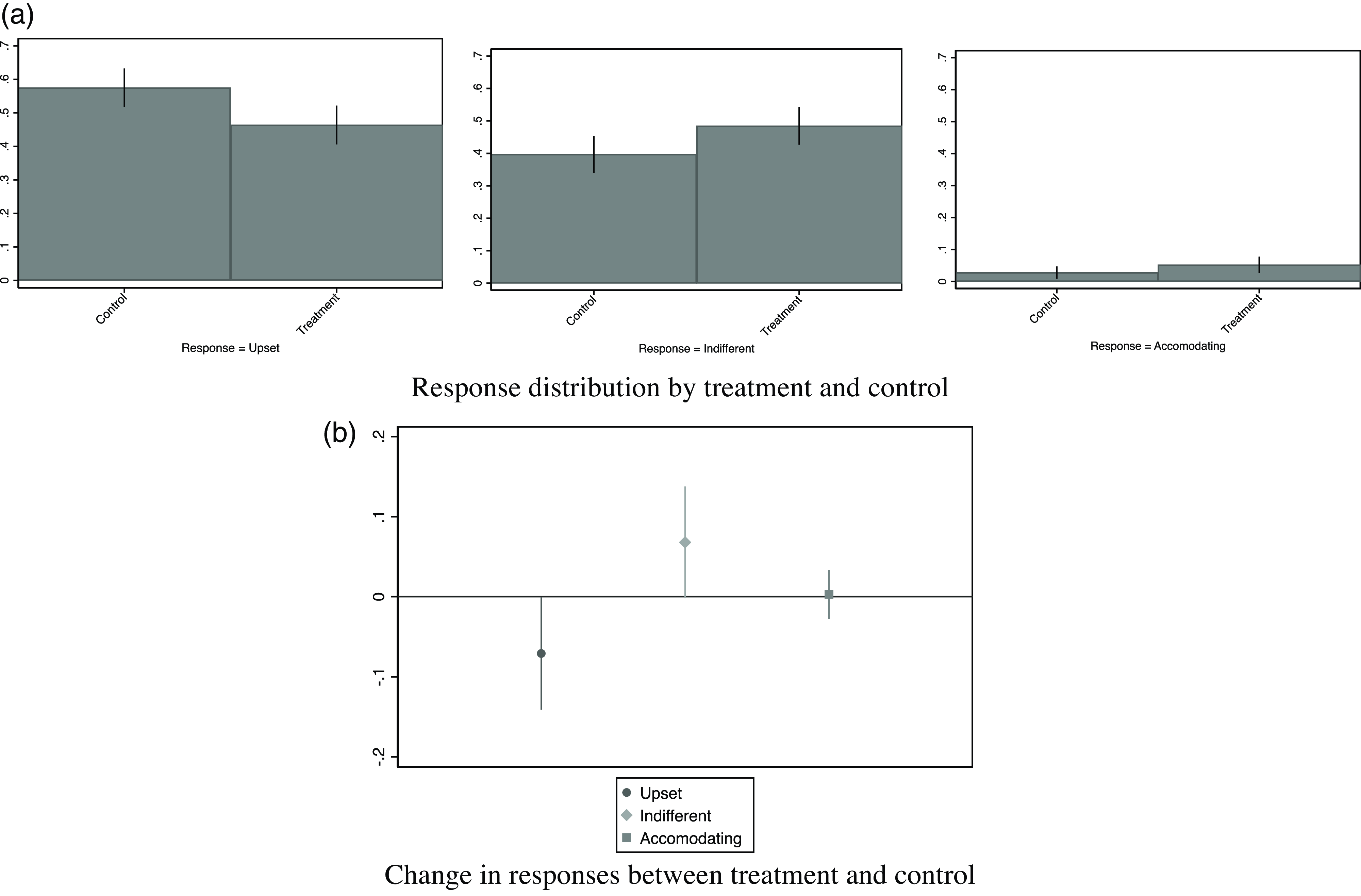

Figure 3. Distribution of reactions to a neighbor coming out by indigeneity rooting treatment and control (with 95 per cent confidence intervals). (a) Response distribution by treatment and control. (b) Change in responses between treatment and control.

Figure 3(a) suggests, when comparing the proportion of people giving each response across treatment and control (rather than the dummy variable operationalization used in the difference-of-means-tests above), that the treatment likely moved many respondents from being upset to being indifferent (as well as moving some from indifference to support) towards a neighbor coming out. Figure 3(b) shows that 8 per cent fewer treated respondents were upset about a neighbor coming out and 7 per cent more were indifferent towards such a neighbor (Table A3 in the Appendix indicates these differences are statistically significant). Treated respondents were only about 2 percentage points likelier to support a neighbor coming out, which suggests that the bulk of the action underlying our treatment effect is moving respondents from being upset to feeling more indifferent. Importantly, the modal response is ‘indifference’ in the treatment group but ‘very upset’ in the control group.

Figure 4. Difference of means tests for liberation rooting treatment.

Note: This figure plots the difference between the liberation prime and the control group along with the 90 per cent and 95 per cent confidence intervals. Positive differences indicate the treatment moved people away from homophobic attitudes.

The indigeneity prime has a significant effect on one of our three measures of attitudes towards the LGBTQ community, meaning it changes people’s reported views immediately after exposure.Footnote 18 While the prime did not significantly change attitudes regarding whether or not being gay is ‘un-African’, it is important to emphasize that the effect is in the expected positive direction and that it did not elicit backlash. The lack of significance on this outcome could also be due to respondents only interacting with a single message rather than a concerted campaign of challenging the un-African frame: Zimbabweans and others across the continent have repeatedly been told by prominent leaders that homosexuality is un-African. The null effect of this prime on equal rights is perhaps less surprising: the prime does not engage with equality or rights directly and thus it may not be sufficient to impact attitudes along this dimension. This, and the results below regarding the liberation prime, suggest that a direct engagement with ‘rights’ is key to moving equal rights attitudes.

For the liberation prime (Figure 4), in every instance, the treatment average is higher than the control average, which once again suggests no evidence of a backlash. We see an effect for one of our outcomes, but in the area we would most expect given the motivation of the liberation message. While the effect is only marginally significant (p = 0.0833), we do find that those who receive the liberation prime are 6 percentage points more likely to agree that homosexuals deserve equal human rights, which provides suggestive evidence in support of H2.Footnote 19 Again, it is perhaps not surprising that this is the outcome for which this prime has an effect. This prime directly links Zimbabwe’s liberation and freedom to the lack of freedom for their fellow LGBTQ citizens.

When considering the degree of agreement, Figure 5(a) suggests that the prime likely moves people from disagreement to indifference and even towards agreement. Figure 5(b) shows that 5 per cent fewer people in the treatment group disagreed with equal rights for homosexual people. This 5 per cent is nearly evenly distributed across those who are indifferent towards rights and those who are supportive (see Appendix Table A5 for difference of means tests). While we cannot trace individual-level shifts in a between-subjects design, the data show movement across the response scale and an overall shift towards greater support for equal rights. When comparing the differences between Figures 4 and 5, the effects are much larger for the indigeneity prime. However, let us emphasize that this positive impact on attitudes towards human rights is also no small feat given the context. Any movement towards more tolerance of equal rights is important, especially for the LGBTQ community in Zimbabwe.

Figure 5. Distribution of agreement with LGBTQ rights by liberation rooting treatment and control (with 95 per cent confidence intervals). (a) Response distribution by treatment and control. (b) Change in responses between treatment and control.

The null results here are perhaps not entirely unexpected, despite our efforts to impact change. As noted above, the ‘un-African’ outcome may not shift with a light-touch, one-off message. The liberation prime, in particular, does not engage directly with the African-ness of homosexuality, and its treatment and control groups show nearly identical averages on that outcome. By contrast, the indigeneity prime group reports a 4 per cent higher average than the control group. The (insignificant) effect of the liberation prime on being upset by a gay neighbor (p = 0.099, one-tailed) is similar in size to its (marginally) significant effect on support for equal rights, suggesting potential for movement. Still, this is speculative, and future research should examine repeated exposure or alternative delivery modes.

We want to emphasize that the effects we detect are quite large in comparison to similar studies in the literature. Lyon’s (Reference Lyon2022) important study also seeks to reduce homophobic attitudes but the effect sizes are close to zero. By contrast, our effects range from a 6 per cent to an 8 per cent change. While homosexuality is more politicized in Lyon’s Uganda, both are contexts in which societal homophobia is high and politics are dominated by a single party in an electoral autocracy. Kalla and Broockman’s (Reference Kalla and Broockman2020) study of transphobia in the United States is another instructive comparison. They introduce a stronger treatment – interpersonal conversation – and find effects roughly on par with our own.Footnote 20 While the outcomes and contexts are different, there is some evidence to suggest that our effects in Zimbabwe are substantive. In short, the impacts our narratives had on respondents are noteworthy. Next, our results are largely robust to estimating multivariate ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analysis with extended controls.Footnote 21 We report regression analyses and interpretation in the Appendix.Footnote 22

A few other insights are important to highlight in addition to our main treatment effects. When designing these treatments, we worried the respondents might resist an unfamiliar historical narrative, but we see no evidence of this. While there is no significant difference in the ‘importance of history’ outcome across either treatment (see Appendix for these results), in both cases, those in the treatment group agree that history is important at higher rates (6 percentage points for indigeneity and 1 percentage point for liberation) than those in the control group: learning something new (knowledge of pre-colonial LGBTQ lives is uncommonFootnote 23 ) seems to suggest to respondents that they do not know their full history and have more to learn and understand, which is true of all of us. Our primes possibly made people think through this and its implications. There is also little reason to believe that social desirability bias (SDB) or demand effects are driving our results, as we discuss in detail in the Appendix. SDB may work in the opposite direction in this context, potentially suppressing pro-LGBTQ responses. To be sure, there is always a possibility that some respondents do not want to be perceived negatively by another person (the enumerator), but even if this is the case for some respondents, a desire to express more ‘agreeable’ views is potentially part of the process that individuals might go through to get to a meaningful change in their views and attitudes.

Finally, as noted for each treatment above, in no instance is the treatment group’s average response lower than the control’s. It is higher in all six cases across Figures 2 and 4 – offering no evidence of backlash to rooted narratives (see Appendix Tables A2 and A4 for the difference of means tests). This finding, combined with the point about the importance of history, suggests that our respondents are open to hearing a more nuanced and complete history that does not erase diversity.

Robustness Test: Additional Data

We further gathered an additional 600 responses to our survey experiment in July 2024 in order to increase our statistical power for the indigeneity prime.Footnote 24 Since a sample of 600 alone is insufficiently powered, we pool these data with the above data (controlling for survey year) and estimate the same tests. The regression results and difference of means test are reported in Appendix Tables A10 and A11. The main finding from this analysis is that our main effect of the indigeneity prime on feelings toward a neighbor coming out remain significant at the 5% level (p = 0.0434). Those who received the treatment are 5 percentage points less likely to be upset over a neighbor coming out as gay (46% compared to 41%).

Correlates of Homophobia

To situate our findings, we compare established drivers of homophobia across Africa to correlates in both our sample and the urban Zimbabwe subsample from Afrobarometer Round 7 (2018). Dionne and Dulani (Reference Dionne and Dulani2013) find that being male, older, and more religious consistently predict homophobia across African contexts, while frequent internet use predicts lower homophobia. Urban residency shows no consistent effect. Using our data, we model predictors of LGBTQ tolerance, controlling for age, gender, education, income, partisanship, community engagement, knowing an LGBTQ person, religious affiliation, religiosity, and internet usage. As shown in Table A6 of the Appendix, older age, ruling party support, and living in Harare predict greater homophobia, while moderate income and knowing an LGBTQ person reduce it. Afrobarometer-data results, though limited by a smaller urban-only sample (n = 400), show effects largely consistent in direction. Compared to broader continental trends, our findings reaffirm the role of age but suggest income and partisanship also matter in urban Zimbabwe. Notably, religiosity does not emerge as a significant predictor of homophobia in our data – an unexpected divergence that future work should explore.

Conclusion

Our findings echo the sentiments of Zimbabwean scholars Togarasei and Chitando (Reference Togarasei and Chitando2011, 122), that insofar as Western discourses dominate the discussion of LGBTQ communities in Africa, ‘the perception [in Africa] that Africa is being “civilized” or talked down to accept same-sex sexuality, it will remain extremely difficult to make headway in changing attitudes towards same-sex relationships’. This insight carries weight for human rights campaigns globally. Even in a challenging rights domain, our experiment has shown that rooting LGBTQ lives in the local context does not hurt the pursuit of LGBTQ inclusion, and in pivotal areas it can reduce homophobia towards neighbors and potentially increase support for equal rights. It also showed that the type of rooted message has differential effects on certain attitudes, with messages drawing on indigenous history leading to a greater willingness to live next to queer neighbors, and ones that invoked a national struggle for rights (the liberation frame) leading to a response more sympathetic to increasing LGBTQ rights. In sum, rooted messages tend to work, even in a case that we consider to be an especially hard case – in global comparison – for promoting LGBTQ human rights.

Such rooted appeals are one way to address the complex role of the West in the issues surrounding LGBTQ lives in the Global South. It is clear that norms that support LGBTQ rights (Ayoub Reference Ayoub2016), as well as ones that seek to retrench them (Velasco Reference Velasco2023), are circulating in world politics. How social movement actors package this information – to broker a resonance locally – matters for shaping attitudes. Of course, this work is done by both proponents and opponents of LGBTQ rights, and for the former, this study shows such rooting work is critical for countering myths of queer impositions and foreignness. It does so by heeding the insights of queer scholars and activists who have insisted we pay close attention to the ways movements can affirm the authenticity and legitimacy of queer identities by rooting them in indigenous traditions and histories, challenging both colonial legacies and contemporary homophobia.Footnote 25 Further, as anti-West and anti-colonial attitudes continue to grow across the African continent (for example the 2023 citizen-supported coup in Niger, or the surge in anti-French sentiment in Mali and Burkina Faso), it will be important for LGBTQ activists to have evidence about the limited harm of such messages.

Indeed, it is striking how important history is to making sense of current affairs. As scholar–activists from Rodney (Reference Rodney1972) to Nyabola (Reference Nyabola2022) have argued, we cannot divorce the current affairs of Africa from its colonial past. This is the case for LGBTQ individuals across the continent, whose past has been erased. Bringing history, accurately and cogently, into politics and public discourse is not a simple task, as Zimbabwean activists made clear during our interviews (see Appendix 3), but when possible to do safely, it may be worth the effort given its potential impacts and the lack of backlash. To be sure, rooting LGBTQ rights in national narratives also faces internal debate. Activists we spoke with (in our focus groups and also from other countries) emphasized that while rooted messages can dislodge the ‘foreign imposition’ narrative, they also require careful, deliberate work to avoid reinforcing exclusionary (homo)nationalist tropes (Puar Reference Puar2007). This is not about folding LGBTQ lives neatly into dominant narratives, but queering them – disrupting the imagination of who is seen as part of the nation in the first place. That is a sensitive task, but increasingly necessary when queer people are framed as a threat to the nation itself.

Future research will have to study these impacts further, including our intuition that in-person and in-depth discussions may further persuade people in ways that our short primes could not. This first study to systematically test these rooted narratives in Africa offers some modest optimism for the frames that may work at dislodging the foreign imposition arguments used by opponents of LGBTQ rights the world over. For example, activists could make use of the history of marriages between Gikuyu women in pre-colonial Kenya (Njambi and O’Brien Reference Njambi, O’Brien and Oyěwùmí2005), queer art and mythology in ancient Egypt (Dowson Reference Dowson, Giffney and O’Rourke2009), celebrated national icons like Pyotr Tchaikovsky in Russia, or religious histories in Poland (Ayoub and Chetaille Reference Ayoub and Chetaille2020). In countries around the world, there are similarly rooted queer histories and narratives, from language to art and literature, that activists can use to enhance the local resonance of their messages.

While this study tests two rooted messages in a single context, future work would do well to continue to test various messages and types of delivery across contexts, to understand how and under what conditions rooting messages effectively combat exclusion. Indeed, the charge of ‘foreign imposition’ is commonly associated with minorities and their rights in countries where their visibility is low. This study could be replicated in a variety of other contexts where activists are innovating with rooted frames. In some contexts, it may also be possible to make messages more ‘forceful’ (given we weakened ours for a context that had little familiarity with discussing queer content), or to test them with in-depth discussions, repeated exposure, or, alternatively, in online settings where respondents feel more comfortable responding freely to queer questions (Messing et al. Reference Messing, Ságvári and Szeitl2025). Finally, we see the importance of thinking further about who is sending these messages, in a way that combines work like ours on the message itself with studies that have focused on the messengers (see, for example, Lyon (Reference Lyon2022), Ayoub et al. (Reference Ayoub, Page and Whitt2025), and Jones (Reference Jones2022), who focused on type of ‘countries’, ‘leaders’, or ‘queer subjects’ as messengers, respectively).

Though we focus on LGBTQ rights, this research contributes to a wider literature on how to mobilize support for contested human rights in difficult contexts. First, in line with Coppock (Reference Coppock2022), people may be movable, which means packaging contentious norms and policies in ways that are rooted could lead to more support. In an era of populist nationalism, where human rights are often positioned as global intrusion, the case of LGBTQ framing in Zimbabwe offers important lessons for political science. Given the ‘post-liberal’ state of current affairs, the established local/global interactions for affecting progressive social change will need to be supplemented with bespoke frames guided by local civil society. Many issues, from women’s rights to racial justice movements, are also painted as ‘foreign intrusion’, so the case study at hand offers guidance. It might also speak to efforts to counter pernicious polarization, where rooted messages may find more common resonance in politically fragmented societies (McCoy et al. Reference McCoy, Press, Somer and Tuncel2022). Our short and simple narratives did move some people’s attitudes positively, even within a context where prevailing opposition to homosexuality was high.

These findings also have important implications for policy and transnational advocacy. For policymakers, liberation frames (when guided by local civil society) may help make protective rights towards LGBTQ people more palatable to the general population. While we do not think that such rights will be easy to propose in Zimbabwe, the parliamentarians who are courageous enough to counter false narratives targeting queer communities can draw on resonant liberation struggles. For transnational advocacy, our study offers evidence for why such actors should lead with rooted messaging, but in ways that empower and follow the lead of local civil society who will know what these messages are (Ayoub and Rainer Reference Ayoub and Rainer2025). In doing so, transnational engagement would be sensitive to the local political and cultural landscape, avoiding highly visible symbolic gestures (such as embassy rainbow flag-waving) that may backfire or reinforce narratives of ‘foreignness’ (Lopez Ortega and Noh Reference Lopez Ortega and Noh2024). Instead, partnerships with local actors – on their terms – can facilitate quieter but more durable progress. Our findings lend support to prior research (see, for example, Devereaux Evans Reference Devereaux Evans2023) calling for more discreet and contextually embedded forms of transnational solidarity.

Finally, the findings also suggest that education about LGBTQ history is key to producing change. Of course, this is an old truism in LGBTQ activism, but the continued importance of education – even in an age of greater understanding and science around LGBTQ identities – remains an essential ingredient for change. This point is all the more meaningful given the ongoing legislative battles to remove such history in education in many states, for example in the United States, Hungary, and Ghana.

Importantly, our sample seemed not to reject an unfamiliar history and rather, at least to some degree, to seriously consider it and accept it as possible. If our enumerator training is any reflection of our respondents, most were surprised when we presented this ‘new’ information but then actively discussed and researched the cave paintings that had previously been made invisible to them. Importantly, given the contemporary political context for LGBTQ people in many African states, we have a clear responsibility to curb the peddling of false narratives originating from the West; it is often Western actors who help craft the ‘neocolonial threat’ message and send the money that funds anti-LGBTQ movements to African states (Velasco Reference Velasco2023). Once again, rooted messages like those tested here have the potential to combat these false narratives. And they are less likely to cause harm.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123425101051.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/1NOW6U.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the activists and enumerators in Zimbabwe who generously shared their time, expertise, and experiences with us; we learned immensely from their insights, and this project would not have been possible without them. Earlier versions of this paper benefited from invaluable feedback at the 2024 American Political Science Association Annual Meeting in Philadelphia, as well as presentations at the Department of Political Science at University College London, the University of Glasgow, the Department of Politics and International Relations at Royal Holloway, and the CEU’s Democracy Institute. We owe special thanks to the following colleagues for their thoughtful comments and encouragement: Taraf Abu Hamdan, Samer Anabtawi, Kristin Bakke, Janina Beiser-McGrath, Lucy Barnes, Jaimie Bleck, Andrea Calflisch, Peter Dinesen, Sarah Dreier, Ioanna Gkoutna, Kat Gupta, Alex Hartman, Finn Klebe, Kelly Kollman, Andrea Krizsan, Ben Lauderdale, Moritz Marbach, Nils Metternich, Conor O’Dwyer, Tom O’Grady, Michal Ovadek, Jenn Piscopo, Dorottya Redai, Julia de Romemont, Kristopher Velasco, Meredith Weiss, Sam Whitt, Ellie Woodhouse, Violetta Zentai, and Ellen Lust (alongside the Governance and Local Development Institute). Ayoub thanks the Independent Social Research Foundation (ISRF) for the time afforded by a Mid-Career Fellowship to complete the last stage of work on this article. We are also exceptionally grateful to the anonymous reviewers and editors at British Journal of Political Science for their generous, incisive, and constructive feedback throughout the review process. Any remaining errors are our own.

Financial support

This research was supported by the UCL Department of Political Science’s Departmental Research Fund and the UCL-Wits Strategic Fund.

Competing interests

None to disclose.